French Third Republic

Encyclopedia

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France

from 1870, when the Second French Empire

collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

, to 1940, when France was overrun

by Nazi Germany

during World War II

, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France and the Vichy France

puppet government

.

Maurice Larkin (2002) argued that political France of the Third Republic was sharply polarized. On the left marched democratic France, heir to the French Revolution

and fully assured of the power of reason and knowledge to create a better future for all Frenchmen and all mankind. On the right stood conservative France, rooted in the peasantry, the Church and the army, and skeptical about "progress" unless guided by traditional elites. Adolphe Thiers

called republicanism in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least". The Third Republic endured seventy years, making it the longest lasting government in France since the collapse of the Ancien Régime

in the French Revolution of 1789.

of 1870–1871 resulted in the defeat of France, and the overthrow of Emperor Napoleon III and his Second French Empire

. After Napoleon's capture by the Prussians in the Battle of Sedan

, Parisian Deputies established the Government of National Defence as a provisional government on 4 September 1870. This first Government of the Third Republic, headed by the President, General Louis Jules Trochu

, ruled during the Siege of Paris

(19 September 1870 - 28 January 1871). As Paris was cut off from the rest of unoccupied France, the Minister of the Interior, Léon Gambetta

, governed the provinces from the city of Tours

.

After the French surrender in January 1871, the Government of National Defence disbanded and national elections (excepting the territories occupied by Prussia) to create a new French government took place. The resulting conservative National Assembly elected Adolphe Thiers

as head of a provisional government, nominally (head of the executive power of the Republic until the institutions of France are decided). Due to the political climate in Paris, the conservative government was based at Versailles.

The new government negotiated the peace settlements with the newly proclaimed German Empire

, resulting in the Treaty of Frankfurt

, signed on 10 May 1871. To oblige the Prussians to leave France, the government passed a variety of financial laws, such as the controversial Law of Maturities, to pay reparations. In Paris, resentment against the government arose and from April – May 1871 Paris workers and National Guards

revolted and established the Paris Commune

, which maintained a radical left-wing regime for two months until its bloody suppression by Thiers' government in May 1871. The following repression of the would have disastrous consequences for the labor movement.

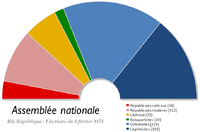

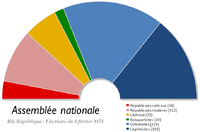

The French legislative election

The French legislative election

, held in the aftermath of the collapse of the regime of Napoleon III, resulted in a monarchist majority in the French National Assembly, favourable to peace with Prussia. The Legitimists

supported the heirs to Charles X

, recognising as king his grandson, Henri, Comte de Chambord

, alias Henry V. The Orléanist

s supported the heirs to Louis Philippe I, recognising as king his grandson, Louis-Philippe, Comte de Paris. The Bonapartists were marginalized due to the defeat of Napoléon III. Legitimists and Orléanists came to a compromise, eventually, whereby the childless would be recognised as king, with the recognised as his heir. Consequently, in 1871 the throne was offered to the . In 1830, Charles X had abdicated in favour of Chambord, then a child (his father having died already), and Louis-Philippe had been recognised as king instead.

In 1871, Chambord had no wish to be a constitutional monarch, but a semi-absolutist one like his grandfather Charles X, or like the contemporary rulers of Prussia/Germany. Moreover, he refused to reign over a state that used the Tricolore

that was associated with the Revolution of 1789 and the July Monarchy

of the man who seized the throne from him in 1830, the citizen-king, Louis Philippe I, King of the French. This became the ultimate reason the restoration never occurred. As much as France wanted a restored monarchy, the nation was unwilling to abandon the popular Tricolore. Instead a "temporary" republic was established, to await the death of the aging, childless Chambord, when the throne could be offered to his more liberal heir, the . However, Chambord lived on until 1883, by which time enthusiasm for monarchy had faded.

. At its apex was a President of the Republic. A two-chamber parliament (featuring a directly elected Chamber of Deputies and an indirectly elected Senate) was created, along with a ministry under the "President of the Council", who was nominally answerable to both the President of the Republic and parliament. Throughout the 1870s, the issue of monarchy versus republic dominated public debate.

On 16 May 1877, with public opinion swinging heavily in favour of a republic, the President of the Republic, Patrice de Mac-Mahon, himself a monarchist, made one last desperate attempt to salvage the monarchical cause by dismissing the republican prime minister Jules Simon

and appointing the monarchist leader the to office. He then dissolved parliament and called a general election for that October. If his hope had been to halt the move towards republicanism, it backfired spectacularly, with the President being accused of having staged a constitutional coup d'état, known as after the date on which it happened.

Republicans returned triumphant during the October elections for the Chamber of Deputies. The prospect of a monarchical restoration died definitively after the republicans gained control of the Senate on 5 January 1879. Mac-Mahon himself resigned on 30 January 1879, leaving a seriously weakened presidency in the shape of Jules Grévy

. Indeed it was not until Charles de Gaulle

, 80 years later, that a President of France next unilaterally dissolved parliament.

in 1877, Legitimists were pushed out of power, and the Republic was finally governed by republicans, called Opportunist Republicans

as they were in favor of moderate changes in order to firmly establish the new regime. The Jules Ferry laws

on free, mandatory and secular public education

, voted in 1881 and 1882, were one of the first signs of this republican control of the Republic, as public education was no longer the exclusive control of the Catholic congregations.

In 1889, the Republic was rocked by the sudden but short-lived Boulanger

crisis, while the Dreyfus Affair

was another important event, spawning the rise of the modern intellectual (Émile Zola

) and the separation of Church and State. Later, the Panama scandals also were quickly criticized by the press.

In 1893, following anarchist Auguste Vaillant

's bombing at the National Assembly

, killing nobody but injuring one, deputies voted the which limited the 1881 freedom of the press

laws. The following year, president Sadi Carnot

was stabbed to death by the Italian anarchist Sante Geronimo Caserio. Also in 1894, 30 alleged anarchists were judged during the Trial of the thirty

.

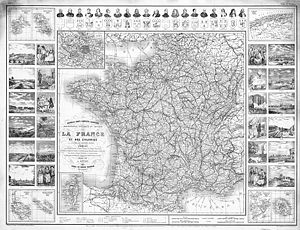

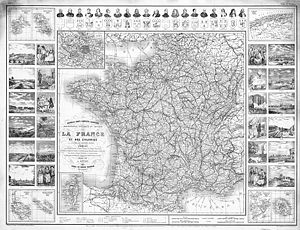

traced the modernization of French villages and argued that rural France went from backward and isolated to modern and possessing a sense of French nationhood during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He emphasized the roles of railroads, republican schools, and universal military conscription. He based his findings on school records, migration patterns, military service documents and economic trends. Weber argued that until 1900 or so a sense of French nationhood was weak in the provinces. Weber then looked at how the policies of the Third Republic created a sense of French nationality in rural areas. The book was widely praised, but was criticized by some who argued that a sense of Frenchness existed in the provinces before 1870.

France successfully integrated the colonies into its economic system. By 1939 one third of its exports went to its colonies; Paris businessmen invested heavily in agriculture, mining, and shipping. In Indochina new plantations were opened for rubber and rice. In Algeria land held by rich settlers rose from 1,600,000 hectares in 1890 to 2,700,000 hectares in 1940; combined with similar operations in Morocco and Tunisia, the result was that North African agriculture became one of the most efficient in the world. Metropolitan France was a captive market, so large landowners could borrow large sums in Paris to modernize agricultural techniques with tractors and mechanized equipment. The result was a dramatic increase in the export of wheat, corn, peaches, and olive oil. Algeria became the fourth most important wine producer in the world.

Opposition to colonial rule led to rebellions in Morocco in 1925, in Syria in 1926, and in Indochina in 1930, all of which were quickly suppressed by the army.

, founded in 1901 (four years before the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) which unified the various socialist currents), remained the most important party of the Third Republic starting at the end of the 19th century. The same year, followers of Léon Gambetta

, such as Raymond Poincaré

, who would become President of the Council in the 1920s, created the Democratic Republican Alliance

(ARD), which became the main center-right party after World War I and the parliamentary disappearance of monarchists and Bonapartist

s.

Governments during the Third Republic collapsed with regularity, rarely lasting more than a couple of months, as radicals, socialists, liberals, conservatives, republicans and monarchists all fought for control. However others argue that the collapse of governments were a minor side effect of the Republic lacking strong political parties, resulting in coalitions of many parties that routinely lost and gained a few allies. Consequently the change of governments could be seen as little more than a series of ministerial reshuffles, with many individuals carrying forward from one government to the next, often in the same posts.

In 1905, the government introduced the law on the separation of Church and State

, heavily supported by Emile Combes

, who had been strictly enforcing the 1901 voluntary association

law and the 1904 law on religious congregations' freedom of teaching (more than 2,500 private teaching establishments were by then closed by the State, causing bitter opposition from the Catholic and conservative population).

in 1892. Due to disease, inefficiency, widespread corruption, the Panama Canal Company handling the massive project went bankrupt, with millions in losses.

The Dreyfus Affair

was even more important, this time involving the French military. In 1894, a Jewish artillery officer, Alfred Dreyfus

, was arrested on charges relating to conspiracy and espionage. Allegedly, Dreyfus had handed over important military documents discussing the designs of a new French artillery piece to a German military attaché named Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen. In 1898, writer Émile Zola

published an article entitled (I accuse...!). The article alleged an anti-Semitic conspiracy in the highest ranks of the military to scapegoat Dreyfus, tacitly supported by the government and the Catholic Church. The real culprit was found two years later to be a high-ranking military officer and aristocrat, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

, but only in 1906 was Dreyfus given a formal pardon and freed after serving twelve years behind bars in Devil's Island

, a Penal Colony

in French Guiana.

in 1894 after diplomatic talks between Germany and Russia had failed to produce any working agreement. The alliance with Russia was to serve as the cornerstone of French foreign policy until 1917. A further link with Russia was provided by vast French investments in and loans to that country before 1914. In 1904, French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé

negotiated with Lord Lansdowne

, the British Foreign Secretary, the Entente Cordiale

, which ended a long period of Anglo-French tensions and hostility. The entente cordiale, which functioned as an informal Anglo-French alliance, was further strengthened by the First

and Second

Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911, and by secret military and naval staff talks. Delcassé's rapprochement with Britain was controversial in France as Anglophobia

was prominent at the turn of the century, sentiments that had been much reinforced by the Fashoda Incident

of 1898, where Britain and France had almost gone to war, and by the Boer War

where French public opinion was very much on the side of Albion’s enemies. Ultimately, the fear of German power proved to be the link that bound Britain and France together.

France entered World War I to defend against German invasion. Germany declared war on France because it feared encirclement and sought to avoid fighting a long war on two fronts, given that France and Russia were bound by a defensive military alliance. Germany sought to win a quick war in the west before Russia fully mobilized its armed forces. The French victory at the Battle of the Marne

in September 1914 ensured the failure of Germany's strategy to avoid a protracted war on two fronts.

Some French intellectuals welcomed the war to avenge the humiliation of defeat and loss of territory to Germany following the Franco-Prussian War

of 1871 (). Paul Déroulède

's anti-semitic (Patriots League), created in 1882, advocated this revenge, for example. This nationalism was also one of the causes of the low popularity of the "colonial lobby", gathering a few politicians, businessmen and geographers favorable to colonialism, until 1918. Thus, Georges Clemenceau

(a Radical), declared that colonialism

diverted France from the "blue line of the Vosges

", referring to the disputed Alsace-Lorraine

region. Other opponents of the colonialist lobby included socialist leader Jean Jaurès

and the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès

, while supporters included Jules Ferry

(moderate republican

), Léon Gambetta

(republican), and Eugène Étienne, the president of the parliamentary colonial group.

After and pacifist

leader Jean Jaurès's

assassination, a few days before the German invasion of Belgium which marked the beginning France's participation in World War I

, the French socialist movement, as the whole of the Second International

, abandoned its antimilitarist positions and joined the national war effort. Georges Clemenceau

, nicknamed "the Tiger", would lead the government after 1917, obtaining the SFIO socialist party's support in the , or "Sacred Union". As in other countries, a state of emergency

was proclaimed and censorship

imposed, leading to the creation in 1915 of the satirical newspaper to bypass the censorship. Furthermore, a war economy

began to be implemented. This war economy would have important consequences after the war, as it would be a first breach against liberal

theories of non-interventionism.

After the outbreak of the war in August 1914, France enjoyed relatively little success. In order to uplift the French national spirit, many intellectual

s began to fashion numerous pieces of wartime propaganda

. The Union sacrée sought to draw the French people closer to the actual front and thus garner social, political, and economic support for the French Armed Forces. However, the Sacred Union had all but disappeared by 1917 as the French Army was dealt a series of catastrophic blows when its offensives were cut down by German machine gun barrages. These successive defeats gave rise after the Second Battle of the Aisne

to mutinies along the Front

. According to American historian Leonard V. Smith, as many as thirty thousand French soldiers engaged in mutinous activities during 1917 alone. Still, the French government, led by Clemenceau, insisted on victory at all costs and therefore the French persisted in their efforts to defeat the Germans.

was led by Georges Clemenceau

(1841–1929, Raymond Poincaré

(1850–1934) and Aristide Briand

(1862–1932). The Bloc was supported by business and finance, and was friendly toward the Army and the church. Its main goals were revenge against Germany, economic prosperity for French business, and stability in domestic affairs. The left-center Cartel des gauches

, dominated by Édouard Herriot

of the Radical Socialist party, was neither radical nor socialist but represented the interests of small business and the lower middle class. It was intensely anti-clerical, and resisted the Catholic Church. The Cartel was occasionally willing to form a coalition with the Socialist Party. Anti-democratic groups, such as the Communists on the left and royalists on the right, played relatively minor roles.

The flow of reparation from Germany played a central role in French finances. The government had begun a large-scale reconstruction program to repair wartime damages, and had a large public debt. Taxation policies were inefficient, with widespread evasion, and when the financial crisis grew worse in 1926, Poincaré levied new taxes, reformed the system of tax collection, and drastically reduced government spending in order to balance the budget and stabilize the franc. Holders of the national debt lost 80% of the face value of their bonds, but runaway inflation did not happen. From 1926 to 1929, the French economy prospered and manufacturing flourished. The Great Depression

hit France later than other countries, and in milder form. Nevertheless, in 1935, 750,000 workers were unemployed, and many others were working part-time. Industrial production grew by 40% between 1913 and 1930, then in 1932 fell back to 1913 levels.

in 1919, but felt betrayed by President Woodrow Wilson

, when his promises that the United States would join the League and sign a defense treaty with France were rejected by Congress. The main goal of French foreign policy was to preserve French power, and neutralize the threat posed by Germany. When Germany fell behind in reparations payments, France seized the industrialized Ruhr region. That proved a fiasco, and Paris did not again attempt unilateral action against Germany. Instead Paris created a paper wall of defensive treaties against Germany with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. In the end, these all proved worthless. It also constructed a powerful defensive wall—a network of fortresses—along the German border called the Maginot Line

, which it trusted as a perfect defense. In 1940, however, the German army simply went around it.

, kept the name Socialist, and by 1932 greatly outnumbered the disorganized Communists. In 1936, the Socialists and the Radicals formed a coalition, with Communist support, called the Popular Front

. Its victory in the elections of the spring of 1936 brought to power a left-wing government headed by Blum. In two years in office it focused on labor law changes sought by the trade unions, especially the mandatory 40-hour work week, down from 48 hours. All workers were given a two-week paid vacation. A collective bargaining law facilitated union growth; membership soared from 1,000,000 to 5,000,000 in one year, and workers' political strength was enhanced when the Communist and non-Communist unions joined together. The government nationalized the armaments industry, and tried to seize control of the Bank of France, in an effort to break the power of the richest 200 families. Farmers received higher prices, and the government purchased surplus wheat, but farmers had to pay higher taxes. Wave after wave of strikes hit French industry in 1936. Wage rates went up 48%, but the work week was cut back by 17%, and the cost of living rose 46%, so there was little real gain to the average worker. The higher prices for French products resulted in a decline in sales overseas, which the government tried to neutralize by devaluing the franc and thus reducing the value of bonds and savings accounts. The overall result was significant damage to the French economy, and a lower rate of growth Most historians judge the Popular Front a failure, although some call it a partial success. There is general agreement that it failed to live up to the expectations of the left.

, foremost among them André Tardieu

. The Revue des deux Mondes

, with its prestigious past and sharp articles, was a major conservative organ. The Catholic Church played a very important role throughout the period, especially by forming youth movements. For example, the largest organization of young working women was the Jeunesse Ouvrière Chrétienne/Féminine (JOC/F). It encouraged young working women to adopt Catholic approaches to morality and to prepare for future roles as mothers at the same time as it promoted notions of spiritual equality and encouraged young women to take active, independent, and public roles in the present.

On the far right were several shrill, but small, groupings that preached doctrines similar to fascism. The most influential was Action Française

, founded in 1905 by the vitriolic author Charles Maurras

(1868–1952). It was intensely nationalistic, anti-Semitic and reactionary, calling for a return to the monarchy and domination of the state by the Catholic Church. However, the Vatican repudiated the Action Française in 1926, and it lost its popular influence, only to be revived during the Vichy government in 1940–1944.

, and with Great Britain, appeased the Germans by giving in to their demands. Intensive rearmament programs began in 1936 and were redoubled in 1938, but they would only bear fruit in 1939 and 1940.

Historians have debated two themes regarding the unexpected, sudden collapse of France in 1940. The first emphasizes the long run, highlighting failures, internal dissension, and a sense of malaise. The second theme blames the poor military planning by the French High Command

. According to the British historian Julian Jackson, the Dyle Plan

conceived by French General Maurice Gamelin

was destined for failure since it drastically miscalculated the ensuing attack by German Army Group B

into central Belgium

. The Dyle Plan embodied the primary war plan of the French Army

to stave off German Army Groups A, B, and C with their much revered Panzer

divisions in Belgium. However, because of the over-stretched positions of the French 1st, 7th, and 9th armies in Belgium at the time of the invasion, the Germans simply outflanked the French by coming through the Ardennes

. As a result of this poor military strategy, France was forced to come to terms with Nazi Germany

in an armistice

signed on 22 June 1940 in the same railway carriage where the Germans had signed the armistice ending the First World War on 11 November 1918.

The Third Republic officially ended on 10 July 1940 when the parliament gave full powers to Philippe Pétain

, who proclaimed in the following days the État Français

(the "French State"), which replaced the Republic.

Throughout its seventy-year history, the Third Republic stumbled from crisis to crisis, from dissolved parliaments to the appointment of a mentally ill president

. It struggled through World War I

against the German Empire

and the inter-war years saw much political strife with a growing rift between the right and the left. When France was liberated in 1944, few called for a restoration of the Third Republic, and a Constituent Assembly was established in 1946 to draft a constitution

for a successor, established as the Fourth Republic

that December, a parliamentary system not unlike the Third Republic.

, first president of the Third Republic, called republicanism

in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least." France might have agreed about being a republic, but it never fully agreed with the Third Republic. France's longest lasting régime since before the 1789 Revolution

, the Third Republic was consigned to the history books as being unloved and unwanted in the end. And yet its longevity showed that it was capable of weathering many storms.

One of the most surprising aspects of the Third Republic was that it constituted the first stable republican government in French history, and the first to win the support of the majority of the population, yet it was intended as an interim, temporary government. Following Thiers's example, most of the Orleanist

monarchists progressively rallied themselves to the Republican institutions, thus giving support of a large part of the elites to the Republican form of government. On the other hand, the Legitimists continued to be harshly anti-Republicans, while Charles Maurras

founded the in 1898, a monarchist far-right movement which would be very influential in the in the 1930s. It would also be one of the model of the various far right leagues

, which participated to the 6 February 1934 riots which succeeded in toppling the Second government.

The Third Republic ended in defeat against the Nazi war machine – historian Marc Bloch

wrote a famous book about this, titled The Strange Defeat.

). Proponents of the concept have argued that the French defeat of 1940 was caused by what they regard as the innate decadence and moral rot of France. The notion of la décadence as an explanation for the defeat began almost as soon as the armistice was signed in June 1940. Marshal Philippe Pétain

stated in a radio broadcast that "The regime led the country to ruin" and in another that "Our defeat is punishment for our moral failures", and claimed that France had "rotted" under the Third Republic. In 1942, there occurred the Riom Trial

when several of the former leaders of the Third Republic were brought to trial for declaring war on Germany in 1939 and not doing enough to prepare France for war. Marc Bloch

in his book Strange Defeat (written in 1940, and published posthumously in 1946) argued that the French upper classes had ceased to believe in the greatness of France following the Popular Front

victory of 1936, and so had allowed themselves to fall under the spell of fascism and defeatism. The French journalist André Géraud, who wrote under the pen name Pertinax

in his 1943 book, The Gravediggers of France indicted the pre-war leadership for what he regarded as total incompetence.

After 1945, the concept of was widely embraced by different French political fractions as a way of discrediting their rivals. The French Communist Party

blamed the defeat on the "corrupt" and "decadent" capitalist Third Republic, (conveniently omitting from this narrative their own sabotaging of the French war effort during the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and opposition to the "imperialist war" against Germany in 1939–40). From a different perspective, Gaullists

damned the Third Republic as a "weak" regime, and argued that if France had a 5th Republic type regime headed by a strong-man president like Charles de Gaulle

before 1940, the defeat could have been avoided. A group of French historians centered around Pierre Renouvin

and his protégés Jean-Baptiste Duroselle and Maurice Baumont started a new type of international history that included taking into what Renouvin called (profound forces) such as the influence of domestic politics on foreign policy. However, Renouvin and his followers still followed the concept of with Renouvin arguing that French society under the Third Republic was “sorely lacking in initiative and dynamism” and Baumont arguing that French politicians had allowed "personal interests" to override "any sense of the general interest". In 1979, Duroselle published a well-known book entitled that offered a total condemnation of the entire Third Republic as weak, cowardly and degenerate. Even more so then in France, the concept of was accepted in the English-speaking world, where British historians such A. J. P. Taylor

often described the Third Republic as a tottering regime on the verge of collapse. A notable example of the thesis was William L. Shirer

's 1969 book The Collapse of the Third Republic

, where the French defeat is explained as the result of the moral weakness and cowardice of the French leaders. Shirer portrayed Édouard Daladier

as a well-meaning, but weak willed; Georges Bonnet

as a corrupt opportunist even willing to do a deal with the Nazis; Marshal Maxime Weygand

as a reactionary soldier more interested in destroying the Third Republic than in defending it; General Maurice Gamelin

as incompetent and defeatist, Pierre Laval

as a crooked crypto-fascist; Charles Maurras

(whom Shirer represented as France’s most influential intellectual) as the preacher of “drivel”; Marshal Philippe Pétain

as the senile puppet of Laval and the French royalists, and Paul Reynaud

as a petty politician controlled by his mistress, Countess Hélène de Portes. Modern historians who subscribe to argument or take a very critical view of France's pre-1940 leadership without necessarily subscribing to la décadence thesis include Talbot Imlay, Anthony Adamthwaite, Serge Berstein, Michael Carely, Nicole Jordan, Igor Lukes, and Richard Crane.

The first historian to explicitly denounce la décadence concept was the Canadian historian Robert J. Young

, who in his 1978 book In Command of France argued that French society was not decadent, that the defeat of 1940 was due to military factors, not moral failures, and that the Third Republic’s leaders had done their best under the difficult conditions of the 1930s. Young has been followed by other historians such as Robert Frankenstein, Jean-Pierre Azema

, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, Martin Alexander, Eugenia Kiesling, and Martin Thomas

who have argued that French weakness on the international stage was due to structural factors as the impact of the Great Depression

had on French rearmament and had nothing to do with French leaders being too “decadent” and cowardly to stand up to Nazi Germany.

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

from 1870, when the Second French Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

, to 1940, when France was overrun

Battle of France

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France and the Vichy France

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

puppet government

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

.

Maurice Larkin (2002) argued that political France of the Third Republic was sharply polarized. On the left marched democratic France, heir to the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

and fully assured of the power of reason and knowledge to create a better future for all Frenchmen and all mankind. On the right stood conservative France, rooted in the peasantry, the Church and the army, and skeptical about "progress" unless guided by traditional elites. Adolphe Thiers

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers was a French politician and historian. was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871...

called republicanism in the 1870s "the form of government that divides France least". The Third Republic endured seventy years, making it the longest lasting government in France since the collapse of the Ancien Régime

Ancien Régime in France

The Ancien Régime refers primarily to the aristocratic, social and political system established in France from the 15th century to the 18th century under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties...

in the French Revolution of 1789.

Background

The Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

of 1870–1871 resulted in the defeat of France, and the overthrow of Emperor Napoleon III and his Second French Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

. After Napoleon's capture by the Prussians in the Battle of Sedan

Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War on 1 September 1870. It resulted in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and large numbers of his troops and for all intents and purposes decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, though fighting continued under a new French...

, Parisian Deputies established the Government of National Defence as a provisional government on 4 September 1870. This first Government of the Third Republic, headed by the President, General Louis Jules Trochu

Louis Jules Trochu

Louis Jules Trochu was a French military leader and politician. He served as President of the Government of National Defense—France's de facto head of state—from 4 September 1870 until his resignation on 22 January 1871 .- Military career :He was born at Palais...

, ruled during the Siege of Paris

Siege of Paris

The Siege of Paris, lasting from September 19, 1870 – January 28, 1871, and the consequent capture of the city by Prussian forces led to French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the German Empire as well as the Paris Commune....

(19 September 1870 - 28 January 1871). As Paris was cut off from the rest of unoccupied France, the Minister of the Interior, Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta was a French statesman prominent after the Franco-Prussian War.-Youth and education:He is said to have inherited his vigour and eloquence from his father, a Genovese grocer who had married a Frenchwoman named Massabie. At the age of fifteen, Gambetta lost the sight of his right eye...

, governed the provinces from the city of Tours

Tours

Tours is a city in central France, the capital of the Indre-et-Loire department.It is located on the lower reaches of the river Loire, between Orléans and the Atlantic coast. Touraine, the region around Tours, is known for its wines, the alleged perfection of its local spoken French, and for the...

.

After the French surrender in January 1871, the Government of National Defence disbanded and national elections (excepting the territories occupied by Prussia) to create a new French government took place. The resulting conservative National Assembly elected Adolphe Thiers

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers was a French politician and historian. was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871...

as head of a provisional government, nominally (head of the executive power of the Republic until the institutions of France are decided). Due to the political climate in Paris, the conservative government was based at Versailles.

The new government negotiated the peace settlements with the newly proclaimed German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, resulting in the Treaty of Frankfurt

Treaty of Frankfurt (1871)

The Treaty of Frankfurt was a peace treaty signed in Frankfurt on 10 May 1871, at the end of the Franco-Prussian War.- Summary :The treaty did the following:...

, signed on 10 May 1871. To oblige the Prussians to leave France, the government passed a variety of financial laws, such as the controversial Law of Maturities, to pay reparations. In Paris, resentment against the government arose and from April – May 1871 Paris workers and National Guards

National Guard (France)

The National Guard was the name given at the time of the French Revolution to the militias formed in each city, in imitation of the National Guard created in Paris. It was a military force separate from the regular army...

revolted and established the Paris Commune

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists and Marxists had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class during the Industrial Revolution...

, which maintained a radical left-wing regime for two months until its bloody suppression by Thiers' government in May 1871. The following repression of the would have disastrous consequences for the labor movement.

Prospects of a parliamentary monarchy

French legislative election, February 1871

French legislative elections to elect the first legislature of the French Third Republic were held on 8 February 1871.This election was held during an explosive situation in the country: following the Franco-Prussian War, 43 departments were occupied. Thus, all public meetings were outlawed...

, held in the aftermath of the collapse of the regime of Napoleon III, resulted in a monarchist majority in the French National Assembly, favourable to peace with Prussia. The Legitimists

Legitimists

Legitimists are royalists in France who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession of the descendants of the elder branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They reject the claim of the July Monarchy of 1830–1848, whose kings were members of the junior...

supported the heirs to Charles X

Charles X of France

Charles X was known for most of his life as the Comte d'Artois before he reigned as King of France and of Navarre from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. A younger brother to Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him...

, recognising as king his grandson, Henri, Comte de Chambord

Henri, comte de Chambord

Henri, comte de Chambord was disputedly King of France from 2 to 9 August 1830 as Henry V, although he was never officially proclaimed as such...

, alias Henry V. The Orléanist

Orléanist

The Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

s supported the heirs to Louis Philippe I, recognising as king his grandson, Louis-Philippe, Comte de Paris. The Bonapartists were marginalized due to the defeat of Napoléon III. Legitimists and Orléanists came to a compromise, eventually, whereby the childless would be recognised as king, with the recognised as his heir. Consequently, in 1871 the throne was offered to the . In 1830, Charles X had abdicated in favour of Chambord, then a child (his father having died already), and Louis-Philippe had been recognised as king instead.

In 1871, Chambord had no wish to be a constitutional monarch, but a semi-absolutist one like his grandfather Charles X, or like the contemporary rulers of Prussia/Germany. Moreover, he refused to reign over a state that used the Tricolore

Flag of France

The national flag of France is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured royal blue , white, and red...

that was associated with the Revolution of 1789 and the July Monarchy

July Monarchy

The July Monarchy , officially the Kingdom of France , was a period of liberal constitutional monarchy in France under King Louis-Philippe starting with the July Revolution of 1830 and ending with the Revolution of 1848...

of the man who seized the throne from him in 1830, the citizen-king, Louis Philippe I, King of the French. This became the ultimate reason the restoration never occurred. As much as France wanted a restored monarchy, the nation was unwilling to abandon the popular Tricolore. Instead a "temporary" republic was established, to await the death of the aging, childless Chambord, when the throne could be offered to his more liberal heir, the . However, Chambord lived on until 1883, by which time enthusiasm for monarchy had faded.

The Government

In February 1875, a series of parliamentary Acts established the organic or constitutional laws of the new republicFrench Constitutional Laws of 1875

The Constitutional Laws of 1875 are the laws passed in France by the National Assembly between February and July 1875 which established the Third French Republic.The constitution laws could be roughly divided into three laws:...

. At its apex was a President of the Republic. A two-chamber parliament (featuring a directly elected Chamber of Deputies and an indirectly elected Senate) was created, along with a ministry under the "President of the Council", who was nominally answerable to both the President of the Republic and parliament. Throughout the 1870s, the issue of monarchy versus republic dominated public debate.

On 16 May 1877, with public opinion swinging heavily in favour of a republic, the President of the Republic, Patrice de Mac-Mahon, himself a monarchist, made one last desperate attempt to salvage the monarchical cause by dismissing the republican prime minister Jules Simon

Jules Simon

Jules François Simon was a French statesman and philosopher, and one of the leader of the Opportunist Republicans faction.-Biography:Simon was born at Lorient. His father was a linen-draper from Lorraine, who renounced Protestantism before his second marriage with a Catholic Breton. Jules Simon...

and appointing the monarchist leader the to office. He then dissolved parliament and called a general election for that October. If his hope had been to halt the move towards republicanism, it backfired spectacularly, with the President being accused of having staged a constitutional coup d'état, known as after the date on which it happened.

Republicans returned triumphant during the October elections for the Chamber of Deputies. The prospect of a monarchical restoration died definitively after the republicans gained control of the Senate on 5 January 1879. Mac-Mahon himself resigned on 30 January 1879, leaving a seriously weakened presidency in the shape of Jules Grévy

Jules Grévy

François Paul Jules Grévy was a President of the French Third Republic and one of the leaders of the Opportunist Republicans faction. Given that his predecessors were monarchists who tried without success to restore the French monarchy, Grévy is seen as the first real republican President of...

. Indeed it was not until Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

, 80 years later, that a President of France next unilaterally dissolved parliament.

The Opportunist Republicans

Following the 16 May crisis16 May 1877 crisis

The 16 May 1877 crisis was a constitutional crisis in the French Third Republic concerning the distribution of power between the President and the legislature. When the Royalist President Patrice MacMahon dismissed the Opportunist Republican Prime Minister Jules Simon, parliament on 16 May 1877...

in 1877, Legitimists were pushed out of power, and the Republic was finally governed by republicans, called Opportunist Republicans

Opportunist Republicans

The Opportunist Republicans , also known as the Moderates , were a faction of French Republicans who believed, after the proclamation of the Third Republic in 1870, that the regime could only be consolidated by successive phases...

as they were in favor of moderate changes in order to firmly establish the new regime. The Jules Ferry laws

Jules Ferry laws

The Jules Ferry Laws are a set of French Laws which established free education , then mandatory and laic education . Jules Ferry, a lawyer holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, is widely credited for creating the modern Republican School...

on free, mandatory and secular public education

Public education

State schools, also known in the United States and Canada as public schools,In much of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the terms 'public education', 'public school' and 'independent school' are used for private schools, that is, schools...

, voted in 1881 and 1882, were one of the first signs of this republican control of the Republic, as public education was no longer the exclusive control of the Catholic congregations.

In 1889, the Republic was rocked by the sudden but short-lived Boulanger

Georges Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger was a French general and reactionary politician. At the apogee of his popularity in January 1889 many republicans including Georges Clemenceau feared the threat of a coup d'état by Boulanger and the establishment of a dictatorship.- Early life and career :Born...

crisis, while the Dreyfus Affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

was another important event, spawning the rise of the modern intellectual (Émile Zola

Émile Zola

Émile François Zola was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism...

) and the separation of Church and State. Later, the Panama scandals also were quickly criticized by the press.

In 1893, following anarchist Auguste Vaillant

Auguste Vaillant

Auguste Vaillant was a French anarchist, most famous for his bomb attack on the French Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1893. The government's reaction to this attack was the passing of the infamous repressive Lois scélérates.He threw the home-made device from the public gallery and was...

's bombing at the National Assembly

French National Assembly

The French National Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of France under the Fifth Republic. The upper house is the Senate ....

, killing nobody but injuring one, deputies voted the which limited the 1881 freedom of the press

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the freedom of communication and expression through vehicles including various electronic media and published materials...

laws. The following year, president Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot was a French statesman and the fourth president of the Third French Republic. He served as the President of France from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.-Early life:...

was stabbed to death by the Italian anarchist Sante Geronimo Caserio. Also in 1894, 30 alleged anarchists were judged during the Trial of the thirty

Trial of the thirty

The Trial of the Thirty was a trial in 1894 in Paris, France, aimed at legitimizing the lois scélérates passed in 1893-1894 against the anarchist movement and restricting press freedom by proving the existence of an effective association between anarchists.Lasting from 6 August-31 October in 1894,...

.

Modernization of the peasants

In his seminal book Peasants Into Frenchmen (1976), historian Eugen WeberEugen Weber

Eugen Joseph Weber was a Romanian-born American historian with a special focus on Western Civilization and the Western Tradition....

traced the modernization of French villages and argued that rural France went from backward and isolated to modern and possessing a sense of French nationhood during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He emphasized the roles of railroads, republican schools, and universal military conscription. He based his findings on school records, migration patterns, military service documents and economic trends. Weber argued that until 1900 or so a sense of French nationhood was weak in the provinces. Weber then looked at how the policies of the Third Republic created a sense of French nationality in rural areas. The book was widely praised, but was criticized by some who argued that a sense of Frenchness existed in the provinces before 1870.

French Empire

The Third Republic, in line with the imperialistic ethos of the day sweeping Europe, developed a worldwide network of colonies. The largest and most important were in North Africa and Vietnam. French administrators, soldiers, and missionaries were dedicated to bringing French civilization to the peoples of the colonies. Some French businessmen went overseas, but there were few permanent settlements. The Catholic Church became deeply involved. Its missionaries were unattached men committed to staying permanently, learning local languages and customs, and converting the natives to Christianity.France successfully integrated the colonies into its economic system. By 1939 one third of its exports went to its colonies; Paris businessmen invested heavily in agriculture, mining, and shipping. In Indochina new plantations were opened for rubber and rice. In Algeria land held by rich settlers rose from 1,600,000 hectares in 1890 to 2,700,000 hectares in 1940; combined with similar operations in Morocco and Tunisia, the result was that North African agriculture became one of the most efficient in the world. Metropolitan France was a captive market, so large landowners could borrow large sums in Paris to modernize agricultural techniques with tractors and mechanized equipment. The result was a dramatic increase in the export of wheat, corn, peaches, and olive oil. Algeria became the fourth most important wine producer in the world.

Opposition to colonial rule led to rebellions in Morocco in 1925, in Syria in 1926, and in Indochina in 1930, all of which were quickly suppressed by the army.

The Radicals' republic

The Radical-Socialist PartyRadical-Socialist Party (France)

The Radical Party , is a liberal and centrist political party in France. The Radicals are currently the fourth-largest party in the National Assembly, with 21 seats...

, founded in 1901 (four years before the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) which unified the various socialist currents), remained the most important party of the Third Republic starting at the end of the 19th century. The same year, followers of Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta was a French statesman prominent after the Franco-Prussian War.-Youth and education:He is said to have inherited his vigour and eloquence from his father, a Genovese grocer who had married a Frenchwoman named Massabie. At the age of fifteen, Gambetta lost the sight of his right eye...

, such as Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France on five separate occasions and as President of France from 1913 to 1920. Poincaré was a conservative leader primarily committed to political and social stability...

, who would become President of the Council in the 1920s, created the Democratic Republican Alliance

Democratic Republican Alliance

The Democratic Republican Alliance was a French political party created in 1901 by followers of Léon Gambetta, such as Raymond Poincaré who would be president of the Council in the 1920s...

(ARD), which became the main center-right party after World War I and the parliamentary disappearance of monarchists and Bonapartist

Bonapartist

In French political history, Bonapartism has two meanings. In a strict sense, this term refers to people who aimed to restore the French Empire under the House of Bonaparte, the Corsican family of Napoleon Bonaparte and his nephew Louis...

s.

Governments during the Third Republic collapsed with regularity, rarely lasting more than a couple of months, as radicals, socialists, liberals, conservatives, republicans and monarchists all fought for control. However others argue that the collapse of governments were a minor side effect of the Republic lacking strong political parties, resulting in coalitions of many parties that routinely lost and gained a few allies. Consequently the change of governments could be seen as little more than a series of ministerial reshuffles, with many individuals carrying forward from one government to the next, often in the same posts.

In 1905, the government introduced the law on the separation of Church and State

1905 French law on the separation of Church and State

The 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and State was passed by the Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1905. Enacted during the Third Republic, it established state secularism in France...

, heavily supported by Emile Combes

Émile Combes

Émile Combes was a French statesman who led the Bloc des gauches's cabinet from June 1902 – January 1905.-Biography:Émile Combes was born in Roquecourbe, Tarn. He studied for the priesthood, but abandoned the idea before ordination. His anti-clericalism would later lead him into becoming a...

, who had been strictly enforcing the 1901 voluntary association

Voluntary association

A voluntary association or union is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement as volunteers to form a body to accomplish a purpose.Strictly speaking, in many jurisdictions no formalities are necessary to start an association...

law and the 1904 law on religious congregations' freedom of teaching (more than 2,500 private teaching establishments were by then closed by the State, causing bitter opposition from the Catholic and conservative population).

Political and military scandals of the 1890s

There were two major scandals that rocked the Third Republic during the 1890s. One entailed the Panama scandalsPanama scandals

The Panama scandals was a corruption affair that broke out in the French Third Republic in 1892, linked to the building of the Panama Canal...

in 1892. Due to disease, inefficiency, widespread corruption, the Panama Canal Company handling the massive project went bankrupt, with millions in losses.

The Dreyfus Affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

was even more important, this time involving the French military. In 1894, a Jewish artillery officer, Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer of Jewish background whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most tense political dramas in modern French and European history...

, was arrested on charges relating to conspiracy and espionage. Allegedly, Dreyfus had handed over important military documents discussing the designs of a new French artillery piece to a German military attaché named Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen. In 1898, writer Émile Zola

Émile Zola

Émile François Zola was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism...

published an article entitled (I accuse...!). The article alleged an anti-Semitic conspiracy in the highest ranks of the military to scapegoat Dreyfus, tacitly supported by the government and the Catholic Church. The real culprit was found two years later to be a high-ranking military officer and aristocrat, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was a commissioned officer in the French armed forces during the second half of the 19th century who has gained notoriety as a spy for the German Empire and the actual perpetrator of the act of treason for which Captain Alfred Dreyfus was wrongfully accused...

, but only in 1906 was Dreyfus given a formal pardon and freed after serving twelve years behind bars in Devil's Island

Devil's Island

Devil's Island is the smallest and northernmost island of the three Îles du Salut located about 6 nautical miles off the coast of French Guiana . It has an area of 14 ha . It was a small part of the notorious French penal colony in French Guiana until 1952...

, a Penal Colony

Penal colony

A penal colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general populace by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory...

in French Guiana.

French foreign policy and the outbreak of the First World War

French foreign policy in the years leading up to the First World War was based largely on hostility to and fear of German power. France secured an alliance with the Russian EmpireRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

in 1894 after diplomatic talks between Germany and Russia had failed to produce any working agreement. The alliance with Russia was to serve as the cornerstone of French foreign policy until 1917. A further link with Russia was provided by vast French investments in and loans to that country before 1914. In 1904, French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé was a French statesman.-Biography:He was born at Pamiers, in the Ariège département...

negotiated with Lord Lansdowne

Henry Petty-FitzMaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne

Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, KG, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, PC was a British politician and Irish peer who served successively as the fifth Governor General of Canada, Viceroy of India, Secretary of State for War, and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs...

, the British Foreign Secretary, the Entente Cordiale

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale was a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial expansion addressed by the agreement, the signing of the Entente Cordiale marked the end of almost a millennium of intermittent...

, which ended a long period of Anglo-French tensions and hostility. The entente cordiale, which functioned as an informal Anglo-French alliance, was further strengthened by the First

First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis was the international crisis over the international status of Morocco between March 1905 and May 1906. Germany resented France's increasing dominance of Morocco, and insisted on an open door policy that would allow German business access to its market...

and Second

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, also called the Second Moroccan Crisis, or the Panthersprung, was the international tension sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat Panther, to the Moroccan port of Agadir on July 1, 1911.-Background:...

Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911, and by secret military and naval staff talks. Delcassé's rapprochement with Britain was controversial in France as Anglophobia

Anglophobia

Anglophobia means hatred or fear of England or the English people. The term is sometimes used more loosely for general Anti-British sentiment...

was prominent at the turn of the century, sentiments that had been much reinforced by the Fashoda Incident

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident was the climax of imperial territorial disputes between Britain and France in Eastern Africa. A French expedition to Fashoda on the White Nile sought to gain control of the Nile River and thereby force Britain out of Egypt. The British held firm as Britain and France were on...

of 1898, where Britain and France had almost gone to war, and by the Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

where French public opinion was very much on the side of Albion’s enemies. Ultimately, the fear of German power proved to be the link that bound Britain and France together.

France entered World War I to defend against German invasion. Germany declared war on France because it feared encirclement and sought to avoid fighting a long war on two fronts, given that France and Russia were bound by a defensive military alliance. Germany sought to win a quick war in the west before Russia fully mobilized its armed forces. The French victory at the Battle of the Marne

First Battle of the Marne

The Battle of the Marne was a First World War battle fought between 5 and 12 September 1914. It resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army under Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. The battle effectively ended the month long German offensive that opened the war and had...

in September 1914 ensured the failure of Germany's strategy to avoid a protracted war on two fronts.

Some French intellectuals welcomed the war to avenge the humiliation of defeat and loss of territory to Germany following the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

of 1871 (). Paul Déroulède

Paul Déroulède

- Early life :Déroulède was born in Paris. He was published first as a poet in the magazine Revue nationale, with the pseudonym "Jean Rebel". In 1869 he produced, at the Théâtre Français, a one-act drama in verse named Juan Strenner.- Military career :...

's anti-semitic (Patriots League), created in 1882, advocated this revenge, for example. This nationalism was also one of the causes of the low popularity of the "colonial lobby", gathering a few politicians, businessmen and geographers favorable to colonialism, until 1918. Thus, Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

(a Radical), declared that colonialism

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire was the set of territories outside Europe that were under French rule primarily from the 17th century to the late 1960s. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second-largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire...

diverted France from the "blue line of the Vosges

Vosges

Vosges is a French department, named after the local mountain range. It contains the hometown of Joan of Arc, Domrémy.-History:The Vosges department is one of the original 83 departments of France, created on February 9, 1790 during the French Revolution. It was made of territories that had been...

", referring to the disputed Alsace-Lorraine

Alsace-Lorraine

The Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after it annexed most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east...

region. Other opponents of the colonialist lobby included socialist leader Jean Jaurès

Jean Jaurès

Jean Léon Jaurès was a French Socialist leader. Initially an Opportunist Republican, he evolved into one of the first social democrats, becoming the leader, in 1902, of the French Socialist Party, which opposed Jules Guesde's revolutionary Socialist Party of France. Both parties merged in 1905 in...

and the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès

Maurice Barrès

Maurice Barrès was a French novelist, journalist, and socialist politician and agitator known for his nationalist and antisemitic views....

, while supporters included Jules Ferry

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.- Early life :Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to...

(moderate republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

), Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta

Léon Gambetta was a French statesman prominent after the Franco-Prussian War.-Youth and education:He is said to have inherited his vigour and eloquence from his father, a Genovese grocer who had married a Frenchwoman named Massabie. At the age of fifteen, Gambetta lost the sight of his right eye...

(republican), and Eugène Étienne, the president of the parliamentary colonial group.

After and pacifist

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

leader Jean Jaurès's

Jean Jaurès

Jean Léon Jaurès was a French Socialist leader. Initially an Opportunist Republican, he evolved into one of the first social democrats, becoming the leader, in 1902, of the French Socialist Party, which opposed Jules Guesde's revolutionary Socialist Party of France. Both parties merged in 1905 in...

assassination, a few days before the German invasion of Belgium which marked the beginning France's participation in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the French socialist movement, as the whole of the Second International

Second International

The Second International , the original Socialist International, was an organization of socialist and labour parties formed in Paris on July 14, 1889. At the Paris meeting delegations from 20 countries participated...

, abandoned its antimilitarist positions and joined the national war effort. Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

, nicknamed "the Tiger", would lead the government after 1917, obtaining the SFIO socialist party's support in the , or "Sacred Union". As in other countries, a state of emergency

State of emergency

A state of emergency is a governmental declaration that may suspend some normal functions of the executive, legislative and judicial powers, alert citizens to change their normal behaviours, or order government agencies to implement emergency preparedness plans. It can also be used as a rationale...

was proclaimed and censorship

Censorship in France

France has a long history of governmental censorship, particularly in the 16th to 18th centuries, but today freedom of press is guaranteed by the French Constitution and instances of governmental censorship are relatively limited and isolated....

imposed, leading to the creation in 1915 of the satirical newspaper to bypass the censorship. Furthermore, a war economy

War economy

War economy is the term used to describe the contingencies undertaken by the modern state to mobilise its economy for war production. Philippe Le Billon describes a war economy as a "system of producing, mobilising and allocating resources to sustain the violence".Many states increase the degree of...

began to be implemented. This war economy would have important consequences after the war, as it would be a first breach against liberal

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is the philosophy committed to the ideal of limited government, constitutionalism, rule of law, due process, and liberty of individuals including freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly, and free markets....

theories of non-interventionism.

After the outbreak of the war in August 1914, France enjoyed relatively little success. In order to uplift the French national spirit, many intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

s began to fashion numerous pieces of wartime propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

. The Union sacrée sought to draw the French people closer to the actual front and thus garner social, political, and economic support for the French Armed Forces. However, the Sacred Union had all but disappeared by 1917 as the French Army was dealt a series of catastrophic blows when its offensives were cut down by German machine gun barrages. These successive defeats gave rise after the Second Battle of the Aisne

Second Battle of the Aisne

The Second Battle of the Aisne , was the massive main assault of the French military's Nivelle Offensive or Chemin des Dames Offensive in 1917 during World War I....

to mutinies along the Front

French Army Mutinies (1917)

The French Army Mutinies of 1917 took place amongst the French troops on the Western Front in Northern France. They started just after the conclusion of the disastrous Second Battle of the Aisne, the main action in the Nivelle Offensive, and involved, to various degrees, nearly half of the French...

. According to American historian Leonard V. Smith, as many as thirty thousand French soldiers engaged in mutinous activities during 1917 alone. Still, the French government, led by Clemenceau, insisted on victory at all costs and therefore the French persisted in their efforts to defeat the Germans.

1919–1939

From 1919 to 1940, France was governed by two main groupings. The right-center Bloc nationalNational Bloc (France)

The National Bloc was a center-right coalition in France which was in power from 1919 to 1924.- Elections of 1919 :Made up primarily of conservative right wing parties, such as the Fédération républicaine, Alliance démocratique, and Action libérale, the coalition had the support of various radical...

was led by Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

(1841–1929, Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Poincaré was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France on five separate occasions and as President of France from 1913 to 1920. Poincaré was a conservative leader primarily committed to political and social stability...

(1850–1934) and Aristide Briand

Aristide Briand

Aristide Briand was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic and received the 1926 Nobel Peace Prize.- Early life :...

(1862–1932). The Bloc was supported by business and finance, and was friendly toward the Army and the church. Its main goals were revenge against Germany, economic prosperity for French business, and stability in domestic affairs. The left-center Cartel des gauches

Cartel des Gauches

The Cartel des gauches was the name of the governmental alliance between the Radical-Socialist Party and the socialist French Section of the Workers' International after World War I , which lasted until the end of the Popular Front . The Cartel des gauches twice won general elections, in 1924 and...

, dominated by Édouard Herriot

Édouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister and for many years as President of the Chamber of Deputies....

of the Radical Socialist party, was neither radical nor socialist but represented the interests of small business and the lower middle class. It was intensely anti-clerical, and resisted the Catholic Church. The Cartel was occasionally willing to form a coalition with the Socialist Party. Anti-democratic groups, such as the Communists on the left and royalists on the right, played relatively minor roles.

The flow of reparation from Germany played a central role in French finances. The government had begun a large-scale reconstruction program to repair wartime damages, and had a large public debt. Taxation policies were inefficient, with widespread evasion, and when the financial crisis grew worse in 1926, Poincaré levied new taxes, reformed the system of tax collection, and drastically reduced government spending in order to balance the budget and stabilize the franc. Holders of the national debt lost 80% of the face value of their bonds, but runaway inflation did not happen. From 1926 to 1929, the French economy prospered and manufacturing flourished. The Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

hit France later than other countries, and in milder form. Nevertheless, in 1935, 750,000 workers were unemployed, and many others were working part-time. Industrial production grew by 40% between 1913 and 1930, then in 1932 fell back to 1913 levels.

Foreign policy