Intellectual

Encyclopedia

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence

(thought and reason) and critical

or analytical

reasoning in either a profession

al or a personal capacity

.

An intellectual is a person who uses thought and reason, intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning, in either a professional or a personal capacity.

, connotes little in the way of ‘public’ rather than ‘literary’ activity.

s to denote contemporary intellectual men; the term rarely denotes ‘scholars

’, and is not synonymous with ‘academic’. Originally, the term implied a distinction, between the literate and the illiterate, which carried great weight when literacy

was rare. It also denoted the ‘literati’ (Latin, pl. of literatus), the ‘citizens of the Republic of Letters

’ in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, where it evolved into the salon

, usually run by women.

, the ‘man of letters’ denotation broadened, to mean ‘specialised’; a man who earned his living writing intellectually, not creatively, about literature

— the essay

ist, the journalist

, the critic

, et al. In the twentieth century, such an approach was gradually superseded by the academic method, and ‘man of letters’ fell into disuse, replaced by the generic ‘intellectual’, a term comprehending intellectual men and women. Its first common usage occurred at the end of the nineteenth century, to denote the defenders of the falsely accused Artillery Officer Alfred Dreyfus

; see below.

speculated upon the concept of the clerisy — as an intellectual class, not as a type of man or woman — as the secular equivalent of the (Anglican) clergy

, whose societal duty is upholding the (national) culture

; like-wise, the concept of the intelligentsia

also approximately from that time, concretely denotes a status class

of ‘mental’ (white-collar

) workers. Alister McGrath

said that ‘[t]he emergence of a socially alienated, theologically literate, anti-establishment lay intelligentsia is one of the more significant phenomena of the social history of Germany in the 1830s’, and that ‘. . . — three or four theological graduates in ten might hope to find employment’ in a church post. As such, politically radical thinkers already had participated in the French Revolution

(1789–99); Robert Darnton

said that they were not societal outsiders, but ‘respectable, domesticated, and assimilated’.

Thenceforth, in Europe

Thenceforth, in Europe

and elsewhere, an ‘intellectual class’ variant has proved societally important, especially to self-styled intellectuals, whose degree of participation in their society’s art

, politics

, journalism

, education

— of either nationalist, internationalist

, or ethnic sentiment — constitute the ‘vocation of the intellectual’. Moreover, some intellectuals were vehemently anti-academic; although universities and their faculties have been synonymous with intellectualism, in other times, centre of gravity of intellectual life has been the academy.

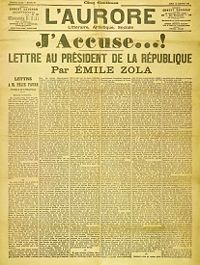

In France, the Dreyfus affair

marked the full emergence of the ‘intellectual in public life’, especially Émile Zola

, Octave Mirbeau

, and Anatole France

directly addressing the matter of French anti-semitism

to the public; thenceforward, ‘intellectual’ became common, yet occasionally derogatory, usage; its French noun

usage is attributed to Georges Clemenceau

, in 1898.

In China

, literati denotes the scholar-bureaucrats

, government officials integral to the ruling class, of more than two thousand years ago. These intellectuals were a status group of educated laymen, whose employment depended upon their commanding knowledge of writing and literature. After 200 BC, Confucianism

influenced the candidate selection system, thus establishing its ethic among the literati. In the Peoples' Republic of China, during the mid-twentieth century, the Hundred Flowers Campaign

(1956–57) — ‘Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land’, proved that mobilising the intellectuals did not always have good consequences.

In Joseon Korea (1392–1910), literati designated the Confucian chungin

(‘middle people’), a petite bourgeoisie

of scholar-bureaucrats (technicians, professionals, scholars) who ensured the Joseon Dynasty’s rule of Korea.

. The public intellectual’s role occasionally overlaps the journalist’s purview (though they are not equivalents); therefore, what distinguishes the public intellectual from the private intellectual?

Regardless of the field of expertise, the role of the public intellectual is addressing and responding to the problems of his or her society as the voice of the people with neither the ability nor the opportunity to address said problems in the public fora. Hence, they must "rise above the partial preoccupation of one’s own profession . . . and engage with the global issues of truth, judgement, and taste of the time." The purpose of the public intellectual is debated, especially his or her place in public discourse, thus acceptance or non-acceptance in contemporary society. To wit, Edward Saïd

noted that as almost impossible:

The intellectual is often associated with political administrations, e.g. the Third Way

centrism of Anthony Giddens

in the Labour Government of Tony Blair. Váçlav Havel

said that politics and intellectuals can be linked, but that responsibility for their ideas, even when advocated by a politician, remains with the intellectual. Therefore, it's best to avoid utopia

n intellectuals, for offering ‘universal insights’ that might, and have, harmed society, proposing, instead, that intellectuals who are mindful of the ties created with their insights, words, and ideas should be ‘. . . listened to with the greatest attention, regardless of whether they work as independent critics, holding up a much-needed mirror to politics and power, or are directly involved in politics’.

— especially philosophy

— who speak about important social and political matters; by definition, the public intellectuals who communicate the theoretic base for resolving public problems; generally, academics remain in their areas of expertise, whereas intellectuals apply academic knowledge and abstraction to public problems.

The sociologist

Frank Furedi

said that ‘Intellectuals are not defined according to the jobs they do, but [by] the manner in which they act, the way they see themselves, and the values that they uphold’; they usually arise from the educated élite, although the North American usage of ‘intellectual’ includes them to the ‘academics’. Convergence with, and participation in, open, contemporary public debate separates intellectuals from academics; by venturing from academic specialism to address the public, the academic becomes a public intellectual. Generally, ‘intellectual’ is a label more often applied to public debate-participants from the fields of culture

, the arts

, and the social sciences

, including the law, than to the men and women working in the natural sciences, the applied sciences, mathematics

, and engineering

.

. Michael Burawoy

, an exponent of public sociology

, criticises ‘professional sociology’ for failing to give sufficient attention to socially important subject matter, blaming academics for losing sight of important public events and issues. Burawoy supports ‘public sociology’ to give the public access to academic research. This process necessitates a dialogue between those in the academic sphere and the public, meant to bridge the gap which still exists between the more homogeneous world of academia and the diverse public sphere. It has been argued that social scientists who are well aware of the various thresholds crossed in passing from academic to public policy adviser are much more effective. A case study on this passage shows how intellectuals worked to re-establish democracy within the Pinochet regime in Chile

. This transition created new professional opportunities for some social scientists, as politicians and consultants, but entailed a shift toward the pragmatic in their politics, and a step away from the neutrality of academia.

C. Wright Mills

, in The Sociological Imagination

, argued that academics had become ill-equipped for the task and that, more often than not, journalists are ‘more politically alert and knowledgeable than sociologists, economists, and especially [...] political scientists’. He went on to criticize the American university system as privatized and bureaucratic, and for failing to teach ‘how to gauge what is going on in the general struggle for power in modern society’. Richard Rorty

was also critical of the ‘civic irresponsibility of intellect, especially academic intellect’.

Richard Posner

concentrates his criticism on "academic public intellectuals"; claiming their declarations to be untidy and biased in ways which would not be tolerated in their academic work. Yet he fears that independent public intellectuals are in decline. Where writing on the academic public intellectual Posner finds that they are only interested in public policy, not with public philosophy, public ethics or public theology, and not with matters of moral and spiritual outrage. Their input has come to be on hard-headed policy questions, rather than values. He also sees a decline in their factual accuracy, linked to a reliance on qualitative and fallible reasoning.

, who disliked the Sophist idea of a public ‘market of ideas’, advocating, instead, a knowledge-monopoly; thus, ‘those who sought a more penetrating and rigorous intellectual life rejected, and withdrew from, the general culture of the city in order to embrace a new model of professionalism’.

Conflicting perspectives about the intellectual established the critical tone about the societal role of the public intellectual. Quite generally, in that perspective, the term ‘intellectual’ has negative connotations in the Netherlands

, as having ‘unrealistic visions of the World’; in Hungary

, as being ‘too-clever’ and an ‘egg-head’; and in the Czech Republic

, as discredited for aloofness from reality; yet Stefan Collini

says that this derogatory usage is not fully representative of the term, as in the ‘. . . case of English usage, positive, neutral, and pejorative uses can easily co-exist’, thus Václav Havel as the exemplar who, ‘. . . to many outside observers [became] a favoured instance of the intellectual as national icon’ in the post–Communist Czech Republic.

The British historian Norman Stone

said that, as a social class

, intellectuals got things badly wrong, doomed to error and stupidity. In her memoirs, the politician Margaret Thatcher

described the French Revolution

(1789–99) as ‘. . . a utopian attempt to overthrow a traditional order . . . in the name of abstract ideas, formulated by vain intellectuals’; nevertheless, as Prime Minister, Thatcher did call upon academics’ help in resolving Britain’s problems — while retaining the popular view of the intellectual as un-British, seconded by newspapers such as The Spectator

, The Sunday Telegraph and documented by the apparent lack of 'intellectuals' in Britain by Collini.

According to a paper by Robert Nozick

at the Cato Institute

, it is more common for intellectuals to have leftist political views than right-wing, arguing that intellectuals were bitter that the skills so rewarded in school were less rewarded in the job market, and so turned against capitalism, even though they enjoyed vastly more enjoyable lives under it than under alternative systems. An analysis made by economist Fredrich Hayek states that intellectuals disproportionately support socialism or have socialist tendencies, which is consistent with the fact that many modern intellectuals, such as Albert Einstein, have had socialist beliefs. In general, most intellectuals in the United States have left-leaning fiscal political viewpoints.

Intellectuals, liberalism and conservatism

Jean Paul Sartre pronounced intellectuals to be the moral conscience of their age, their task being to observe the political and social situation of the moment, and to speak out—freely—in accordance with their consciences (Scriven 1993: 119).

Jean Paul Sartre pronounced intellectuals to be the moral conscience of their age, their task being to observe the political and social situation of the moment, and to speak out—freely—in accordance with their consciences (Scriven 1993: 119).

Like Sartre and Noam Chomsky

, many public intellectuals hold knowledge across a vast array of subjects including: "the international world order, the political and economic organisation of contemporary society, the institutional and legal frameworks that regulate the lives of ordinary citizens, the educational system, and the media networks that control and disseminate information. Sartre systematically refused to keep quiet about what he saw as inequalities and injustices in the world" (Scriven 1999: xii).

Whereas intellectuals, particularly in politics and the social sciences, and social liberals and democratic socialists ordinarily support and engage in democratic principles such as, freedom, equality, justice, human rights, social welfare, the environment and political and social improvement, both domestically and internationally, most conservatives, including Margaret Thatcher

, are interested in upholding security and elitism. This opinion can be seen most readily in the idea that UK foreign policy is shaped and managed by a domestic elite that shares the same viewpoint on all major aspects of foreign policy. According to the historian, Mark Curtis in his book: Web of Deceit: Britain's Real Role in the World, this elite spans the influential figures in all the mainstream parties, the civil service and technocrats who implement the policy, and also senior academic and media figures who help shape public opinion. This elite promotes the basic pillars of Britain's role in the world, such as: strong general support (involving consistent apologia) for US foreign policy and maintaining a special relationship; maintaining a powerful interventionist military capability and using it; promotion of 'free trade' and worldwide economic 'liberalisation'; retention of nuclear weapons; promoting military industry and Britain's role as an arms exporter; and strong support for the traditional order in the Middle East, Gulf regimes and other key bilateral allies (Curtis 2003: 286).

This single ideological foreign policy is exemplified by Bernard Ingham (Margaret Thatcher

's former press spokesman), who stated: "Bugger the public's right to know. The game is the security of the state - not the public's right to know" (Curtis 2003: 285).

onwards) have taken an interest in Marxism from the most varied angles. A widely held view by Marxists is that intellectuals are alienated

and anti-establishment. Although Marx seemed to imply in his reference to intellectuals that they are constantly engaged in an instinctive struggle with established institutions, including the state, 'such a struggle could be carried on within such institutions and in support of established institutions and against change'.

Antonio Gramsci

, a theorist on intellectuals, argued that 'intellectuals view themselves as autonomous from the ruling class'. He suggests that this conceptualisation originates with intellectuals themselves, not with students of intellectual life'. His standpoint is that every social class needs its own intelligentsia

, to shape its ideology

, and that intellectuals must choose their social class. The extent to which ideological currents have influenced the twentieth century milieu has caused some observers of intellectual life to make ideology part of the definition of an intellectual. Lewis Feuer expresses this view when he states that 'no scientist or scholar is regarded as an intellectual unless he adheres to or seems to be searching for an ideology'.

Marxists believe intellectuals resemble the proletarian by reason of their social position, making a living by selling their labour and therefore are often exploited by the power of capital. On the other hand, intellectuals perform mental work, often managerial work, and due to their higher income, they live in a manner comparable to that of the bourgeois. Intellectuals have been neutral instruments in the hands of different social forces. However, Marxists believe that ‘all knowledge is existentially based, and that intellectuals who create and preserve knowledge act as spokesmen for different social groups and articulate particular social interests’. Where Gramsci has said that intellectuals offer their knowledge on the market, Marxists suggest that ‘under modern Western capitalism, the intellectuals make commodities of the ideologies they produce and offer themselves for hire to the real social classes whose ideologies they formulate, whose intelligence they will become’. Marx believed that intellectuals aim to universalise their ideologies ‘then turn about and expose the partiality of those ideologies.’

Yet, for Harding, Marx's theory of the rise of the proletariat was to rely on the intellectuals of that historical period, as stated by Gramsci:

In this situation, as with other areas of society, it is the intellectuals, not the proletariat, who are to define the emancipation of the workers. According to Harding (1997), for the creation of any mass consciousness of ideals, intellectuals are essential. Alongside György Lukács, he also considers that, as a privileged class, it is they, not the workers who can interpret 'totality', giving them the right to be considered leaders. Lenin also maintained that the ideology of socialism

was beyond the comprehension of the working classes. The intellectual level which was necessary for the development of such ideologies was, he maintained, out of the reach of the average worker.

Marxists believe that intellectuals talk and communicate in a certain language that is distinctive to other intellectuals and middle-class populations. Alvin Gouldner labels this language 'critical-reflexive discourse'. By this, Gouldner argues that 'intellectuals universally agree that their positions be defended by rational arguments and that the status of the individual making the argument should have no bearing on the outcome'.

had a negative view of intellectuals, believing they were an enemy to capitalism because a majority of them held socialist beliefs:

, for instance philosopher Steve Fuller said that, because Cultural capital

confers power and status, one must be autonomous in order to be a credible intellectual: ‘It is relatively easy to demonstrate autonomy if you come from a wealthy or [an] aristocratic

background. You simply need to disown your status

and champion the poor and downtrodden. autonomy is much harder to demonstrate if you come from a poor or proletarian background . . . [thus] calls to join the wealthy in common cause appear to betray one’s class origins’. The importance of Émile Zola

in the Dreyfus Affair

derived from his already being a ‘leading French thinker, [that] his letter formed a major turning-point in the affair’. Although he was tried for his political participation in the Dreyfus Affair, he escaped the law by fleeing France, because he was rich.

From the public’s perspective, many of the world’s private and public intellectuals were graduated from élite universities, and, therefore, were educated by the preceding generation of intellectuals, e.g. Noam Chomsky

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

; Richard Dawkins

and Christopher Hitchens

at Oxford University. None the less, the exceptions exist; Harold Pinter

, of a ‘low middle-class background’, was a playwright

, screenplay writer

, actor

, theatre director, poet

, and political activist, whose activities as such rendered him a public intellectual.

has intense public interest, despite the fact that it is an academic specialisation. It provokes debate on an array of socially important issues involving medicine

, technology

, genetic research etc. Examples of scientists who have occupied a unique role in public intellectualism are Richard Dawkins

with his work on evolution

, and Charles Darwin

.

It has been suggested that public intellectuals bridge the gap between the academic elite and the educated public, particularly when concerning issues in the natural sciences like genetics

and bioethics

. There are distinct differences between academics in the traditional sense and public intellectuals. Academics are typically confined to their academy or university and tend to concentrate on their chosen academic discipline. This is usually specific to western academia, following large scale investment into higher education

after the Cold War

and growth in the number of academic institutions. This in turn has led to hyperspecialisation within academic life- the specialization of particular disciplines and confining it to the classroom. This has become known as "the academisation of intellectual life". A public intellectual, although often starting out in academia

, is not confined to a specific discipline or to traditional boundaries. Public intellectuals should not be confused with experts, who are people who have mastery over one specific field of interest. This development has encouraged a gap between academics and the public. Public intellectuals convey information through multiple mediums, often appearing on television

, radio

and in popular literature. As Richard Posner states, "a public intellectual expresses himself in a way that is accessible to the public". They synthesize academic ideas and relate them to wider socio- political issues.

There has been a general call for natural scientists

and bioethicists to play more of a role in public intellectualism as their disciplines have such relevance to civil society

. Scientists and bioethicists already play major roles in review boards, government commissions and ethics committees, it is easy to see how their research can have public relevance. Since academia is hidden away, it has been argued that scientists, and bioethicists in particular should realise their duty to society by assuming the role of a public intellectual. This would mean taking their relevant research

and communicating it through mass media

to the wider concerns of the public. Increased public interest in bioethics has increased the responsibility for bio ethicists to become more engaged in the public domain- not in an expert role, but as instigators of public discourse.

Intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in different ways, including the abilities for abstract thought, understanding, communication, reasoning, learning, planning, emotional intelligence and problem solving....

(thought and reason) and critical

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is the process or method of thinking that questions assumptions. It is a way of deciding whether a claim is true, false, or sometimes true and sometimes false, or partly true and partly false. The origins of critical thinking can be traced in Western thought to the Socratic...

or analytical

Logic

In philosophy, Logic is the formal systematic study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Logic is used in most intellectual activities, but is studied primarily in the disciplines of philosophy, mathematics, semantics, and computer science...

reasoning in either a profession

Profession

A profession is a vocation founded upon specialized educational training, the purpose of which is to supply disinterested counsel and service to others, for a direct and definite compensation, wholly apart from expectation of other business gain....

al or a personal capacity

Individual capacity

In law, individual capacity is a term of art referring to one's status as a natural person, distinct from any other role. For example, an officer, employee or agent of a corporation, acting "in their individual capacity" is acting as himself, rather than as an agent of the corporation...

.

Terminology and endeavours

"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:An intellectual is a person who uses thought and reason, intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning, in either a professional or a personal capacity.

- A person involved in, and with, abstract, eruditeEruditionThe word erudition came into Middle English from Latin. A scholar is erudite when instruction and reading followed by digestion and contemplation have effaced all rudeness , that is to say smoothed away all raw, untrained incivility...

ideas and theories. - A person whose profession (e.g. philosophy, literary criticism, sociology, law, political analysis, theoretical science, etc.) solely involves the production and dissemination of ideas.

- A person of notable cultural and artArtArt is the product or process of deliberately arranging items in a way that influences and affects one or more of the senses, emotions, and intellect....

istic expertise whose knowledge grants him or her intellectual authorityAuthorityThe word Authority is derived mainly from the Latin word auctoritas, meaning invention, advice, opinion, influence, or command. In English, the word 'authority' can be used to mean power given by the state or by academic knowledge of an area .-Authority in Philosophy:In...

in public discourse. - A person of high mental calibre and applied mental agility that can inductivelyInductive reasoningInductive reasoning, also known as induction or inductive logic, is a kind of reasoning that constructs or evaluates propositions that are abstractions of observations. It is commonly construed as a form of reasoning that makes generalizations based on individual instances...

or deductivelyDeductive reasoningDeductive reasoning, also called deductive logic, is reasoning which constructs or evaluates deductive arguments. Deductive arguments are attempts to show that a conclusion necessarily follows from a set of premises or hypothesis...

reason from evidence and patterns, with the creativity to "think outside the box".

Historical perspectives

In English ‘intellectual’ conveys the general notion of a literate thinker; its earlier usage, such as in The Evolution of an Intellectual (1920), by John Middleton MurryJohn Middleton Murry

John Middleton Murry was an English writer. He was prolific, producing more than 60 books and thousands of essays and reviews on literature, social issues, politics, and religion during his lifetime...

, connotes little in the way of ‘public’ rather than ‘literary’ activity.

Men of letters

The term ‘Man of Letters’ (‘belletrist’, from the French belles-lettres), has been used in some Western cultureWestern culture

Western culture, sometimes equated with Western civilization or European civilization, refers to cultures of European origin and is used very broadly to refer to a heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, religious beliefs, political systems, and specific artifacts and...

s to denote contemporary intellectual men; the term rarely denotes ‘scholars

Scholarly method

Scholarly method or scholarship is the body of principles and practices used by scholars to make their claims about the world as valid and trustworthy as possible, and to make them known to the scholarly public.-Methods:...

’, and is not synonymous with ‘academic’. Originally, the term implied a distinction, between the literate and the illiterate, which carried great weight when literacy

Literacy

Literacy has traditionally been described as the ability to read for knowledge, write coherently and think critically about printed material.Literacy represents the lifelong, intellectual process of gaining meaning from print...

was rare. It also denoted the ‘literati’ (Latin, pl. of literatus), the ‘citizens of the Republic of Letters

Republic of Letters

Republic of Letters is most commonly used to define intellectual communities in the late 17th and 18th century in Europe and America. It especially brought together the intellectuals of Age of Enlightenment, or "philosophes" as they were called in France...

’ in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, where it evolved into the salon

Salon (gathering)

A salon is a gathering of people under the roof of an inspiring host, held partly to amuse one another and partly to refine taste and increase their knowledge of the participants through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "either to...

, usually run by women.

Nineteenth-century British usage

In the late eighteenth century, when literacy was relatively common in European countries, such as the United KingdomUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, the ‘man of letters’ denotation broadened, to mean ‘specialised’; a man who earned his living writing intellectually, not creatively, about literature

Literature

Literature is the art of written works, and is not bound to published sources...

— the essay

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

ist, the journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

, the critic

Critic

A critic is anyone who expresses a value judgement. Informally, criticism is a common aspect of all human expression and need not necessarily imply skilled or accurate expressions of judgement. Critical judgements, good or bad, may be positive , negative , or balanced...

, et al. In the twentieth century, such an approach was gradually superseded by the academic method, and ‘man of letters’ fell into disuse, replaced by the generic ‘intellectual’, a term comprehending intellectual men and women. Its first common usage occurred at the end of the nineteenth century, to denote the defenders of the falsely accused Artillery Officer Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer of Jewish background whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most tense political dramas in modern French and European history...

; see below.

Nineteenth-century European modes of the ‘Intellectual Class’

In the early nineteenth century, Samuel Taylor ColeridgeSamuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was an English poet, Romantic, literary critic and philosopher who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets. He is probably best known for his poems The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla...

speculated upon the concept of the clerisy — as an intellectual class, not as a type of man or woman — as the secular equivalent of the (Anglican) clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

, whose societal duty is upholding the (national) culture

Culture

Culture is a term that has many different inter-related meanings. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions...

; like-wise, the concept of the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

also approximately from that time, concretely denotes a status class

Status class

The German sociologist Max Weber formulated a three-component theory of stratification in which he defines status group as a group of people that can be differentiated on the basis of non-economical qualities like honour, prestige and religion...

of ‘mental’ (white-collar

White-collar worker

The term white-collar worker refers to a person who performs professional, managerial, or administrative work, in contrast with a blue-collar worker, whose job requires manual labor...

) workers. Alister McGrath

Alister McGrath

Alister Edgar McGrath is an Anglican priest, theologian, and Christian apologist, currently Professor of Theology, Ministry, and Education at Kings College London and Head of the Centre for Theology, Religion and Culture...

said that ‘[t]he emergence of a socially alienated, theologically literate, anti-establishment lay intelligentsia is one of the more significant phenomena of the social history of Germany in the 1830s’, and that ‘. . . — three or four theological graduates in ten might hope to find employment’ in a church post. As such, politically radical thinkers already had participated in the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789–99); Robert Darnton

Robert Darnton

Robert Darnton is an American cultural historian, recognized as a leading expert on 18th-century France.-Life:He graduated from Harvard University in 1960, attended Oxford University on a Rhodes scholarship, and earned a Ph.D. in history from Oxford in 1964, where he studied with Richard Cobb,...

said that they were not societal outsiders, but ‘respectable, domesticated, and assimilated’.

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and elsewhere, an ‘intellectual class’ variant has proved societally important, especially to self-styled intellectuals, whose degree of participation in their society’s art

Art

Art is the product or process of deliberately arranging items in a way that influences and affects one or more of the senses, emotions, and intellect....

, politics

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

, journalism

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

, education

Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

— of either nationalist, internationalist

Internationalism (politics)

Internationalism is a political movement which advocates a greater economic and political cooperation among nations for the theoretical benefit of all...

, or ethnic sentiment — constitute the ‘vocation of the intellectual’. Moreover, some intellectuals were vehemently anti-academic; although universities and their faculties have been synonymous with intellectualism, in other times, centre of gravity of intellectual life has been the academy.

In France, the Dreyfus affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

marked the full emergence of the ‘intellectual in public life’, especially Émile Zola

Émile Zola

Émile François Zola was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism...

, Octave Mirbeau

Octave Mirbeau

Octave Mirbeau was a French journalist, art critic, travel writer, pamphleteer, novelist, and playwright, who achieved celebrity in Europe and great success among the public, while still appealing to the literary and artistic avant-garde...

, and Anatole France

Anatole France

Anatole France , born François-Anatole Thibault, , was a French poet, journalist, and novelist. He was born in Paris, and died in Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire. He was a successful novelist, with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters...

directly addressing the matter of French anti-semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

to the public; thenceforward, ‘intellectual’ became common, yet occasionally derogatory, usage; its French noun

Noun

In linguistics, a noun is a member of a large, open lexical category whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition .Lexical categories are defined in terms of how their members combine with other kinds of...

usage is attributed to Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was a French statesman, physician and journalist. He served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. For nearly the final year of World War I he led France, and was one of the major voices behind the Treaty of Versailles at the...

, in 1898.

Eastern intellectuals

For much of Indian history, Brahmins have been the majority in intellectual occupations such as teaching and writing. However, following India's independence and introduction of reservations for scheduled castes, the proportions have been increasing in favour of other castes. Brahmins have also increasedly taken to non-intellectual professions.In China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, literati denotes the scholar-bureaucrats

Scholar-bureaucrats

Scholar-officials or Scholar-bureaucrats were civil servants appointed by the emperor of China to perform day-to-day governance from the Sui Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, China's last imperial dynasty. These officials mostly came from the well-educated men known as the...

, government officials integral to the ruling class, of more than two thousand years ago. These intellectuals were a status group of educated laymen, whose employment depended upon their commanding knowledge of writing and literature. After 200 BC, Confucianism

Confucianism

Confucianism is a Chinese ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius . Confucianism originated as an "ethical-sociopolitical teaching" during the Spring and Autumn Period, but later developed metaphysical and cosmological elements in the Han...

influenced the candidate selection system, thus establishing its ethic among the literati. In the Peoples' Republic of China, during the mid-twentieth century, the Hundred Flowers Campaign

Hundred Flowers Campaign

The Hundred Flowers Campaign, also termed the Hundred Flowers Movement, refers mainly to a brief six weeks in the People's Republic of China in the early summer of 1957 during which the Communist Party of China encouraged a variety of views and solutions to national policy issues, launched...

(1956–57) — ‘Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting progress in the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land’, proved that mobilising the intellectuals did not always have good consequences.

In Joseon Korea (1392–1910), literati designated the Confucian chungin

Chungin

The chungin also jungin, were the petite bourgeoisie of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea. The name "chungin" literally means "middle people". This privileged class of commoners consisted of a small group of petty bureaucrats and other skilled workers whose technical and administrative skills enabled the...

(‘middle people’), a petite bourgeoisie

Petite bourgeoisie

Petit-bourgeois or petty bourgeois is a term that originally referred to the members of the lower middle social classes in the 18th and early 19th centuries...

of scholar-bureaucrats (technicians, professionals, scholars) who ensured the Joseon Dynasty’s rule of Korea.

Public intellectual life

The public intellectual handles ideas and knowledge as a participant and communicator in the public debate effected in the mass communications mediaMass media

Mass media refers collectively to all media technologies which are intended to reach a large audience via mass communication. Broadcast media transmit their information electronically and comprise of television, film and radio, movies, CDs, DVDs and some other gadgets like cameras or video consoles...

. The public intellectual’s role occasionally overlaps the journalist’s purview (though they are not equivalents); therefore, what distinguishes the public intellectual from the private intellectual?

Regardless of the field of expertise, the role of the public intellectual is addressing and responding to the problems of his or her society as the voice of the people with neither the ability nor the opportunity to address said problems in the public fora. Hence, they must "rise above the partial preoccupation of one’s own profession . . . and engage with the global issues of truth, judgement, and taste of the time." The purpose of the public intellectual is debated, especially his or her place in public discourse, thus acceptance or non-acceptance in contemporary society. To wit, Edward Saïd

Edward Said

Edward Wadie Saïd was a Palestinian-American literary theorist and advocate for Palestinian rights. He was University Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and a founding figure in postcolonialism...

noted that as almost impossible:

- [The] . . . real or ‘true’ intellectual is, therefore, always an outsider, living in self-imposed exile, and on the margins of society’.

The intellectual is often associated with political administrations, e.g. the Third Way

Third way (centrism)

The Third Way refers to various political positions which try to reconcile right-wing and left-wing politics by advocating a varying synthesis of right-wing economic and left-wing social policies. Third Way approaches are commonly viewed from within the first- and second-way perspectives as...

centrism of Anthony Giddens

Anthony Giddens

Anthony Giddens, Baron Giddens is a British sociologist who is known for his theory of structuration and his holistic view of modern societies. He is considered to be one of the most prominent modern contributors in the field of sociology, the author of at least 34 books, published in at least 29...

in the Labour Government of Tony Blair. Váçlav Havel

Václav Havel

Václav Havel is a Czech playwright, essayist, poet, dissident and politician. He was the tenth and last President of Czechoslovakia and the first President of the Czech Republic . He has written over twenty plays and numerous non-fiction works, translated internationally...

said that politics and intellectuals can be linked, but that responsibility for their ideas, even when advocated by a politician, remains with the intellectual. Therefore, it's best to avoid utopia

Utopia

Utopia is an ideal community or society possessing a perfect socio-politico-legal system. The word was imported from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempt...

n intellectuals, for offering ‘universal insights’ that might, and have, harmed society, proposing, instead, that intellectuals who are mindful of the ties created with their insights, words, and ideas should be ‘. . . listened to with the greatest attention, regardless of whether they work as independent critics, holding up a much-needed mirror to politics and power, or are directly involved in politics’.

Relationship with academia

In some contexts, especially in journalism, ‘intellectual’ generally denotes academics of the humanitiesHumanities

The humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytical, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences....

— especially philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

— who speak about important social and political matters; by definition, the public intellectuals who communicate the theoretic base for resolving public problems; generally, academics remain in their areas of expertise, whereas intellectuals apply academic knowledge and abstraction to public problems.

The sociologist

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

Frank Furedi

Frank Furedi

Frank Furedi is professor of sociology at the University of Kent, United Kingdom. He is well known for his work on sociology of fear, therapy culture, paranoid parenting and sociology of knowledge....

said that ‘Intellectuals are not defined according to the jobs they do, but [by] the manner in which they act, the way they see themselves, and the values that they uphold’; they usually arise from the educated élite, although the North American usage of ‘intellectual’ includes them to the ‘academics’. Convergence with, and participation in, open, contemporary public debate separates intellectuals from academics; by venturing from academic specialism to address the public, the academic becomes a public intellectual. Generally, ‘intellectual’ is a label more often applied to public debate-participants from the fields of culture

Culture

Culture is a term that has many different inter-related meanings. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions...

, the arts

The arts

The arts are a vast subdivision of culture, composed of many creative endeavors and disciplines. It is a broader term than "art", which as a description of a field usually means only the visual arts. The arts encompass visual arts, literary arts and the performing arts – music, theatre, dance and...

, and the social sciences

Social sciences

Social science is the field of study concerned with society. "Social science" is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to a plurality of fields outside of the natural sciences usually exclusive of the administrative or managerial sciences...

, including the law, than to the men and women working in the natural sciences, the applied sciences, mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, and engineering

Engineering

Engineering is the discipline, art, skill and profession of acquiring and applying scientific, mathematical, economic, social, and practical knowledge, in order to design and build structures, machines, devices, systems, materials and processes that safely realize improvements to the lives of...

.

Public policy debate

The role of a public intellectual may be to connect scholarly research with public policyPublic policy (law)

In private international law, the public policy doctrine or ordre public concerns the body of principles that underpin the operation of legal systems in each state. This addresses the social, moral and economic values that tie a society together: values that vary in different cultures and change...

. Michael Burawoy

Michael Burawoy

Michael Burawoy is a British, sociological Marxist, best known as author of Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process under Monopoly Capitalisma study on work and organizations that has been translated into a number of languagesand as the leading proponent of public sociology...

, an exponent of public sociology

Public sociology

Public sociology is an approach to the discipline which seeks to transcend the academy and engage wider audiences. Rather than being defined by a particular method, theory, or set of political values, public sociology may be seen as a style of sociology, a way of writing and a form of intellectual...

, criticises ‘professional sociology’ for failing to give sufficient attention to socially important subject matter, blaming academics for losing sight of important public events and issues. Burawoy supports ‘public sociology’ to give the public access to academic research. This process necessitates a dialogue between those in the academic sphere and the public, meant to bridge the gap which still exists between the more homogeneous world of academia and the diverse public sphere. It has been argued that social scientists who are well aware of the various thresholds crossed in passing from academic to public policy adviser are much more effective. A case study on this passage shows how intellectuals worked to re-establish democracy within the Pinochet regime in Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

. This transition created new professional opportunities for some social scientists, as politicians and consultants, but entailed a shift toward the pragmatic in their politics, and a step away from the neutrality of academia.

C. Wright Mills

C. Wright Mills

Charles Wright Mills was an American sociologist. Mills is best remembered for his 1959 book The Sociological Imagination in which he lays out a view of the proper relationship between biography and history, theory and method in sociological scholarship...

, in The Sociological Imagination

The Sociological Imagination

The Sociological Imagination is a book by American sociologist C. Wright Mills, first published by Oxford University Press in 1959 and still in print....

, argued that academics had become ill-equipped for the task and that, more often than not, journalists are ‘more politically alert and knowledgeable than sociologists, economists, and especially [...] political scientists’. He went on to criticize the American university system as privatized and bureaucratic, and for failing to teach ‘how to gauge what is going on in the general struggle for power in modern society’. Richard Rorty

Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty was an American philosopher. He had a long and diverse academic career, including positions as Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton, Kenan Professor of Humanities at the University of Virginia, and Professor of Comparative Literature at Stanford University...

was also critical of the ‘civic irresponsibility of intellect, especially academic intellect’.

Richard Posner

Richard Posner

Richard Allen Posner is an American jurist, legal theorist, and economist who is currently a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago and a Senior Lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School...

concentrates his criticism on "academic public intellectuals"; claiming their declarations to be untidy and biased in ways which would not be tolerated in their academic work. Yet he fears that independent public intellectuals are in decline. Where writing on the academic public intellectual Posner finds that they are only interested in public policy, not with public philosophy, public ethics or public theology, and not with matters of moral and spiritual outrage. Their input has come to be on hard-headed policy questions, rather than values. He also sees a decline in their factual accuracy, linked to a reliance on qualitative and fallible reasoning.

Critics

The American theologian Edwards A. Park said, ‘we do wrong to our own minds when we carry out scientific difficulties down to the arena of popular dissension’. He wanted ‘to separate the serious technical role of professionals from their responsibility of supplying usable philosophies for the general public’ — the rationale for maintaining the private knowledge–private knowledge dichotomy (reminiscent of the two cultures dichotomy); Bender differentiates between ‘civic culture’ and ‘professional culture’ in describing the different spheres where academics work. This perspective dates from SocratesSocrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

, who disliked the Sophist idea of a public ‘market of ideas’, advocating, instead, a knowledge-monopoly; thus, ‘those who sought a more penetrating and rigorous intellectual life rejected, and withdrew from, the general culture of the city in order to embrace a new model of professionalism’.

Conflicting perspectives about the intellectual established the critical tone about the societal role of the public intellectual. Quite generally, in that perspective, the term ‘intellectual’ has negative connotations in the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, as having ‘unrealistic visions of the World’; in Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, as being ‘too-clever’ and an ‘egg-head’; and in the Czech Republic

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Poland to the northeast, Slovakia to the east, Austria to the south, and Germany to the west and northwest....

, as discredited for aloofness from reality; yet Stefan Collini

Stefan Collini

Stefan Collini is an English literary critic and academic, Professor of English Literature and Intellectual History at the University of Cambridge. He has contributed essays to such publications as The Times Literary Supplement, The Nation and London Review of Books.- Works :* "." The Times...

says that this derogatory usage is not fully representative of the term, as in the ‘. . . case of English usage, positive, neutral, and pejorative uses can easily co-exist’, thus Václav Havel as the exemplar who, ‘. . . to many outside observers [became] a favoured instance of the intellectual as national icon’ in the post–Communist Czech Republic.

The British historian Norman Stone

Norman Stone

Norman Stone is a British academic, historian, author and is currently a Professor in the Department of International Relations at Bilkent University, Ankara...

said that, as a social class

Social class

Social classes are economic or cultural arrangements of groups in society. Class is an essential object of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, economists, anthropologists and social historians. In the social sciences, social class is often discussed in terms of 'social stratification'...

, intellectuals got things badly wrong, doomed to error and stupidity. In her memoirs, the politician Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

described the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789–99) as ‘. . . a utopian attempt to overthrow a traditional order . . . in the name of abstract ideas, formulated by vain intellectuals’; nevertheless, as Prime Minister, Thatcher did call upon academics’ help in resolving Britain’s problems — while retaining the popular view of the intellectual as un-British, seconded by newspapers such as The Spectator

The Spectator

The Spectator is a weekly British magazine first published on 6 July 1828. It is currently owned by David and Frederick Barclay, who also owns The Daily Telegraph. Its principal subject areas are politics and culture...

, The Sunday Telegraph and documented by the apparent lack of 'intellectuals' in Britain by Collini.

According to a paper by Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick was an American political philosopher, most prominent in the 1970s and 1980s. He was a professor at Harvard University. He is best known for his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia , a right-libertarian answer to John Rawls's A Theory of Justice...

at the Cato Institute

Cato Institute

The Cato Institute is a libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1977 by Edward H. Crane, who remains president and CEO, and Charles Koch, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of the conglomerate Koch Industries, Inc., the largest privately held...

, it is more common for intellectuals to have leftist political views than right-wing, arguing that intellectuals were bitter that the skills so rewarded in school were less rewarded in the job market, and so turned against capitalism, even though they enjoyed vastly more enjoyable lives under it than under alternative systems. An analysis made by economist Fredrich Hayek states that intellectuals disproportionately support socialism or have socialist tendencies, which is consistent with the fact that many modern intellectuals, such as Albert Einstein, have had socialist beliefs. In general, most intellectuals in the United States have left-leaning fiscal political viewpoints.

Intellectuals, liberalism and conservatism

Like Sartre and Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, and activist. He is an Institute Professor and Professor in the Department of Linguistics & Philosophy at MIT, where he has worked for over 50 years. Chomsky has been described as the "father of modern linguistics" and...

, many public intellectuals hold knowledge across a vast array of subjects including: "the international world order, the political and economic organisation of contemporary society, the institutional and legal frameworks that regulate the lives of ordinary citizens, the educational system, and the media networks that control and disseminate information. Sartre systematically refused to keep quiet about what he saw as inequalities and injustices in the world" (Scriven 1999: xii).

Whereas intellectuals, particularly in politics and the social sciences, and social liberals and democratic socialists ordinarily support and engage in democratic principles such as, freedom, equality, justice, human rights, social welfare, the environment and political and social improvement, both domestically and internationally, most conservatives, including Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

, are interested in upholding security and elitism. This opinion can be seen most readily in the idea that UK foreign policy is shaped and managed by a domestic elite that shares the same viewpoint on all major aspects of foreign policy. According to the historian, Mark Curtis in his book: Web of Deceit: Britain's Real Role in the World, this elite spans the influential figures in all the mainstream parties, the civil service and technocrats who implement the policy, and also senior academic and media figures who help shape public opinion. This elite promotes the basic pillars of Britain's role in the world, such as: strong general support (involving consistent apologia) for US foreign policy and maintaining a special relationship; maintaining a powerful interventionist military capability and using it; promotion of 'free trade' and worldwide economic 'liberalisation'; retention of nuclear weapons; promoting military industry and Britain's role as an arms exporter; and strong support for the traditional order in the Middle East, Gulf regimes and other key bilateral allies (Curtis 2003: 286).

This single ideological foreign policy is exemplified by Bernard Ingham (Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

's former press spokesman), who stated: "Bugger the public's right to know. The game is the security of the state - not the public's right to know" (Curtis 2003: 285).

Marxism and intellectuals

Marxists interest themselves in the status of intellectuals in a number of ways: their class position, the way they form a reservoir of ideas, and in the public sphere, their ability to interpret and their potential as leaders. At the same time, intellectuals (from Karl MarxKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

onwards) have taken an interest in Marxism from the most varied angles. A widely held view by Marxists is that intellectuals are alienated

Social alienation

The term social alienation has many discipline-specific uses; Roberts notes how even within the social sciences, it “is used to refer both to a personal psychological state and to a type of social relationship”...

and anti-establishment. Although Marx seemed to imply in his reference to intellectuals that they are constantly engaged in an instinctive struggle with established institutions, including the state, 'such a struggle could be carried on within such institutions and in support of established institutions and against change'.

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian writer, politician, political philosopher, and linguist. He was a founding member and onetime leader of the Communist Party of Italy and was imprisoned by Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime...

, a theorist on intellectuals, argued that 'intellectuals view themselves as autonomous from the ruling class'. He suggests that this conceptualisation originates with intellectuals themselves, not with students of intellectual life'. His standpoint is that every social class needs its own intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

, to shape its ideology

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

, and that intellectuals must choose their social class. The extent to which ideological currents have influenced the twentieth century milieu has caused some observers of intellectual life to make ideology part of the definition of an intellectual. Lewis Feuer expresses this view when he states that 'no scientist or scholar is regarded as an intellectual unless he adheres to or seems to be searching for an ideology'.

Marxists believe intellectuals resemble the proletarian by reason of their social position, making a living by selling their labour and therefore are often exploited by the power of capital. On the other hand, intellectuals perform mental work, often managerial work, and due to their higher income, they live in a manner comparable to that of the bourgeois. Intellectuals have been neutral instruments in the hands of different social forces. However, Marxists believe that ‘all knowledge is existentially based, and that intellectuals who create and preserve knowledge act as spokesmen for different social groups and articulate particular social interests’. Where Gramsci has said that intellectuals offer their knowledge on the market, Marxists suggest that ‘under modern Western capitalism, the intellectuals make commodities of the ideologies they produce and offer themselves for hire to the real social classes whose ideologies they formulate, whose intelligence they will become’. Marx believed that intellectuals aim to universalise their ideologies ‘then turn about and expose the partiality of those ideologies.’

Yet, for Harding, Marx's theory of the rise of the proletariat was to rely on the intellectuals of that historical period, as stated by Gramsci:

- A human mass does not 'distinguish' itself, does not become independent in it's own right without, in the widest sense, organising itself; and there is no organisation without intellectuals, that is without organisers and leaders, in other words, without ... a group of people 'specialised' in conceptual and philosophical elaboration of ideas."

In this situation, as with other areas of society, it is the intellectuals, not the proletariat, who are to define the emancipation of the workers. According to Harding (1997), for the creation of any mass consciousness of ideals, intellectuals are essential. Alongside György Lukács, he also considers that, as a privileged class, it is they, not the workers who can interpret 'totality', giving them the right to be considered leaders. Lenin also maintained that the ideology of socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

was beyond the comprehension of the working classes. The intellectual level which was necessary for the development of such ideologies was, he maintained, out of the reach of the average worker.

Marxists believe that intellectuals talk and communicate in a certain language that is distinctive to other intellectuals and middle-class populations. Alvin Gouldner labels this language 'critical-reflexive discourse'. By this, Gouldner argues that 'intellectuals universally agree that their positions be defended by rational arguments and that the status of the individual making the argument should have no bearing on the outcome'.

Economic liberal and classical liberal views of intellectuals

The economist Milton FriedmanMilton Friedman

Milton Friedman was an American economist, statistician, academic, and author who taught at the University of Chicago for more than three decades...

had a negative view of intellectuals, believing they were an enemy to capitalism because a majority of them held socialist beliefs:

The two chief enemies of free enterprise are intellectuals on the one hand and businessmen on the other, for opposite reasons. Every intellectual believes in freedom for himself, but he’s opposed to freedom for others... He thinks... there ought to be a central planning board that will establish social priorities.

Background of public intellectuals

Peter. H. Smith said that ‘people from an identifiable social classSocial class

Social classes are economic or cultural arrangements of groups in society. Class is an essential object of analysis for sociologists, political scientists, economists, anthropologists and social historians. In the social sciences, social class is often discussed in terms of 'social stratification'...

, for instance philosopher Steve Fuller said that, because Cultural capital

Cultural capital

The term cultural capital refers to non-financial social assets; they may be educational or intellectual, which might promote social mobility beyond economic means....

confers power and status, one must be autonomous in order to be a credible intellectual: ‘It is relatively easy to demonstrate autonomy if you come from a wealthy or [an] aristocratic

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

background. You simply need to disown your status

Social status

In sociology or anthropology, social status is the honor or prestige attached to one's position in society . It may also refer to a rank or position that one holds in a group, for example son or daughter, playmate, pupil, etc....

and champion the poor and downtrodden. autonomy is much harder to demonstrate if you come from a poor or proletarian background . . . [thus] calls to join the wealthy in common cause appear to betray one’s class origins’. The importance of Émile Zola

Émile Zola

Émile François Zola was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism...

in the Dreyfus Affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

derived from his already being a ‘leading French thinker, [that] his letter formed a major turning-point in the affair’. Although he was tried for his political participation in the Dreyfus Affair, he escaped the law by fleeing France, because he was rich.

From the public’s perspective, many of the world’s private and public intellectuals were graduated from élite universities, and, therefore, were educated by the preceding generation of intellectuals, e.g. Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, and activist. He is an Institute Professor and Professor in the Department of Linguistics & Philosophy at MIT, where he has worked for over 50 years. Chomsky has been described as the "father of modern linguistics" and...

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

; Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins

Clinton Richard Dawkins, FRS, FRSL , known as Richard Dawkins, is a British ethologist, evolutionary biologist and author...

and Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens is an Anglo-American author and journalist whose books, essays, and journalistic career span more than four decades. He has been a columnist and literary critic at The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Slate, World Affairs, The Nation, Free Inquiry, and became a media fellow at the...

at Oxford University. None the less, the exceptions exist; Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter, CH, CBE was a Nobel Prize–winning English playwright and screenwriter. One of the most influential modern British dramatists, his writing career spanned more than 50 years. His best-known plays include The Birthday Party , The Homecoming , and Betrayal , each of which he adapted to...

, of a ‘low middle-class background’, was a playwright

Playwright

A playwright, also called a dramatist, is a person who writes plays.The term is not a variant spelling of "playwrite", but something quite distinct: the word wright is an archaic English term for a craftsman or builder...

, screenplay writer

Screenwriter

Screenwriters or scriptwriters or scenario writers are people who write/create the short or feature-length screenplays from which mass media such as films, television programs, Comics or video games are based.-Profession:...

, actor

Actor

An actor is a person who acts in a dramatic production and who works in film, television, theatre, or radio in that capacity...

, theatre director, poet

Poet

A poet is a person who writes poetry. A poet's work can be literal, meaning that his work is derived from a specific event, or metaphorical, meaning that his work can take on many meanings and forms. Poets have existed since antiquity, in nearly all languages, and have produced works that vary...

, and political activist, whose activities as such rendered him a public intellectual.

Bioethics and public intellectualism

BioethicsBioethics

Bioethics is the study of controversial ethics brought about by advances in biology and medicine. Bioethicists are concerned with the ethical questions that arise in the relationships among life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, politics, law, and philosophy....

has intense public interest, despite the fact that it is an academic specialisation. It provokes debate on an array of socially important issues involving medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

, technology

Technology

Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;...

, genetic research etc. Examples of scientists who have occupied a unique role in public intellectualism are Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins

Clinton Richard Dawkins, FRS, FRSL , known as Richard Dawkins, is a British ethologist, evolutionary biologist and author...

with his work on evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

, and Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

.

It has been suggested that public intellectuals bridge the gap between the academic elite and the educated public, particularly when concerning issues in the natural sciences like genetics

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

and bioethics

Bioethics