Anti-intellectualism

Encyclopedia

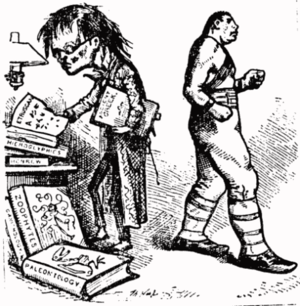

Anti-intellectualism is hostility towards and mistrust of intellect

Intellect

Intellect is a term used in studies of the human mind, and refers to the ability of the mind to come to correct conclusions about what is true or real, and about how to solve problems...

, intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

s, and intellectual pursuits

Intellectualism

Intellectualism denotes the use and development of the intellect, the practice of being an intellectual, and of holding intellectual pursuits in great regard. Moreover, in philosophy, “intellectualism” occasionally is synonymous with “rationalism”, i.e. knowledge derived mostly from reason and...

, usually expressed as the derision of education

Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

, philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, literature

Literature

Literature is the art of written works, and is not bound to published sources...

, art

Art

Art is the product or process of deliberately arranging items in a way that influences and affects one or more of the senses, emotions, and intellect....

, and science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

, as impractical and contemptible. Alternately, self-described intellectuals who are alleged to fail to adhere to rigorous standards of scholarship may be described as anti-intellectuals.

In public discourse, anti-intellectuals usually perceive and publicly present themselves as champions of the common folk — populists

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

against political elitism

Elitism

Elitism is the belief or attitude that some individuals, who form an elite — a select group of people with intellect, wealth, specialized training or experience, or other distinctive attributes — are those whose views on a matter are to be taken the most seriously or carry the most...

and academic elitism

Academic elitism

Academic elitism is a charge sometimes levied at academic institutions and academics more broadly, arguing that academia or academics are prone to undeserved and/or pernicious elitism; the term "ivory tower" often carries with it an implicit critique of academic elitism...

— proposing that the educated are a social class detached from the everyday concerns of the majority, and that they dominate political

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

discourse and higher education

Higher education

Higher, post-secondary, tertiary, or third level education refers to the stage of learning that occurs at universities, academies, colleges, seminaries, and institutes of technology...

.

As a political adjective, 'anti-intellectual' variously describes an education

Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

system emphasising minimal academic accomplishment, and a government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

who formulate public policy

Public policy

Public policy as government action is generally the principled guide to action taken by the administrative or executive branches of the state with regard to a class of issues in a manner consistent with law and institutional customs. In general, the foundation is the pertinent national and...

without the advice of academics

Academia

Academia is the community of students and scholars engaged in higher education and research.-Etymology:The word comes from the akademeia in ancient Greece. Outside the city walls of Athens, the gymnasium was made famous by Plato as a center of learning...

and their scholarship

Scholarly method

Scholarly method or scholarship is the body of principles and practices used by scholars to make their claims about the world as valid and trustworthy as possible, and to make them known to the scholarly public.-Methods:...

. Because "anti-intellectual" can be a pejorative

Pejorative

Pejoratives , including name slurs, are words or grammatical forms that connote negativity and express contempt or distaste. A term can be regarded as pejorative in some social groups but not in others, e.g., hacker is a term used for computer criminals as well as quick and clever computer experts...

, defining specific cases of anti-intellectualism can be troublesome; one can object to specific facets of intellectualism or the application thereof without being dismissive of intellectual pursuits in general. Moreover, allegations of anti-intellectualism can constitute an appeal to authority or an appeal to ridicule

Appeal to ridicule

Appeal to ridicule, also called appeal to mockery, the Horse Laugh, or reductio ad ridiculum , is a logical fallacy which presents the opponent's argument in a way that appears ridiculous, often to the extent of creating a straw man of the actual argument, rather than addressing the argument itself...

that attempt to discredit an opponent rather than specifically addressing his or her arguments.

Anti-intellectualism perhaps saw its most extreme form during the 1970s

1970s

File:1970s decade montage.png|From left, clockwise: US President Richard Nixon doing the V for Victory sign after his resignation from office after the Watergate scandal in 1974; Refugees aboard a US naval boat after the Fall of Saigon, leading to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975; The 1973 oil...

in Cambodia

Cambodia

Cambodia , officially known as the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia...

under the rule of Pol Pot

Pol Pot

Saloth Sar , better known as Pol Pot, , was a Cambodian Maoist revolutionary who led the Khmer Rouge from 1963 until his death in 1998. From 1976 to 1979, he served as the Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea....

and the Khmer Rouge

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge literally translated as Red Cambodians was the name given to the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, who were the ruling party in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, led by Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Son Sen and Khieu Samphan...

, when people were killed for being academics or even for wearing eyeglasses in the Killing Fields.

Anti-intellectualism expressed

Anti-intellectualism usually is expressed through declarations of otherOther

The Other or Constitutive Other is a key concept in continental philosophy; it opposes the Same. The Other refers, or attempts to refer, to that which is Other than the initial concept being considered...

ness — the intellectual is “not one of us” and may be dangerous, due to having little empathy for the common folk. Historically, this resulted in portrayals of intellectuals as an arrogant class, whom rural communities viewed as “city slickers” indifferent to country ways; such communities tended to stereotype

Stereotype

A stereotype is a popular belief about specific social groups or types of individuals. The concepts of "stereotype" and "prejudice" are often confused with many other different meanings...

intellectuals as foreigners or as racial and ethnic minorities who “think differently” than the natives. Religious critics describe intellectuals as prone to mental instability, proposing an organic, causal connection between genius

Genius

Genius is something or someone embodying exceptional intellectual ability, creativity, or originality, typically to a degree that is associated with the achievement of unprecedented insight....

and madness; they are unlike regular people because of their assumed atheism

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

, and are indecent given their sexual mores

Sexual ethics

Sexual ethics refers to those aspects of ethics that deal with issues arising from all aspects of sexuality and human sexual behavior...

, homosexuality

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

, sexual promiscuity

Promiscuity

In humans, promiscuity refers to less discriminating casual sex with many sexual partners. The term carries a moral or religious judgement and is viewed in the context of the mainstream social ideal for sexual activity to take place within exclusive committed relationships...

, or celibacy

Celibacy

Celibacy is a personal commitment to avoiding sexual relations, in particular a vow from marriage. Typically celibacy involves avoiding all romantic relationships of any kind. An individual may choose celibacy for religious reasons, such as is the case for priests in some religions, for reasons of...

.

Economist Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell is an American economist, social theorist, political philosopher, and author. A National Humanities Medal winner, he advocates laissez-faire economics and writes from a libertarian perspective...

argues for distinctions between unreasonable and reasonable wariness of intellectuals. Defining intellectuals as "people whose occupations deal primarily with ideas" as distinct from those who apply ideas practically, Sowell argues that there can be good cause for distrust of intellectuals. When working in their fields of expertise, intellectuals have increased knowledge. However, when compared to other careers, Sowell suggests intellectuals have few disincentives for speaking outside their expertise, and are less likely to face the consequences of their errors. For example, a physician is judged by effective treatment, yet might face malpractice

Malpractice

In law, malpractice is a type of negligence in, which the professional under a duty to act, fails to follow generally accepted professional standards, and that breach of duty is the proximate cause of injury to a plaintiff who suffers harm...

lawsuits if he harms a patient. In contrast, a university professor with tenure

Tenure

Tenure commonly refers to life tenure in a job and specifically to a senior academic's contractual right not to have his or her position terminated without just cause.-19th century:...

is less likely to be judged by the effectiveness of his ideas and less likely to face repercussions for his errors:

- By encouraging, or even requiring, students to take stands where they have neither the knowledge nor the intellectual training to seriously examine complex issues, teachers promote the expression of unsubstantiated opinions, the venting of uninformed emotions, and the habit of acting on those opinions and emotions, while ignoring or dismissing opposing views, without having either the intellectual equipment or the personal experience to weigh one view against another in any serious way.

Similar arguments have been made by others. Historian Paul Johnson argued that a close examination of 20th century history reveals that intellectuals have championed innumerable disastrous public policies, writing, "beware intellectuals. Not merely should they be kept well away from the levers of power, they should also be objects of suspicion when they seek to offer collective advice." Journalist Tom Wolfe

Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly "Tom" Wolfe, Jr. is a best-selling American author and journalist. He is one of the founders of the New Journalism movement of the 1960s and 1970s.-Early life and education:...

described an intellectual as "a person knowledgable in one field who speaks out only in others."

Religion

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

(ca. 8th c. BC–AD 600) and in the Modern

Modern history

Modern history, or the modern era, describes the historical timeline after the Middle Ages. Modern history can be further broken down into the early modern period and the late modern period after the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution...

era (ca. 1500), religion tended to anti-intellectual sentiment — usually among fundamentalists

Fundamentalism

Fundamentalism is strict adherence to specific theological doctrines usually understood as a reaction against Modernist theology. The term "fundamentalism" was originally coined by its supporters to describe a specific package of theological beliefs that developed into a movement within the...

who perceived doctrinal

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

contradictions allowing - instead of the philosophical of perception but pure empirical method of thinking through strict and accurate scientific experiment to prove and validate. Yet, said sentiment have limits, e.g. Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

’s scholarly

Scholarly method

Scholarly method or scholarship is the body of principles and practices used by scholars to make their claims about the world as valid and trustworthy as possible, and to make them known to the scholarly public.-Methods:...

and theologic

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

traditions, and the Western university system

History of European research universities

European research universities date from the founding of the University of Bologna in 1088 or the University of Paris . In the 19th and 20th centuries, European universities concentrated upon science and research, their structures and philosophies having shaped the contemporary university...

were confined under religious authorities. Hypatia's murder was one example marked the end of classical antiquity and the decay of scientific philosophy tradition. The following medieval dark age and even at modern industrial revolution era some philosophers

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

— Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

, René Descartes

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

, John Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher from Königsberg , researching, lecturing and writing on philosophy and anthropology at the end of the 18th Century Enlightenment....

— considered themselves religious without contradicting their intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

ism; see the Conflict Thesis

Conflict thesis

The conflict thesis proposes an intrinsic intellectual conflict between religion and science. The original historical usage of the term denoted that the historical record indicates religion’s perpetual opposition to science. Later uses of the term denote religion’s epistemological opposition to...

for further discussion of religious anti-intellectualism.

When doctrine

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

stipulates definitive statements about natural

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

and human history

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

to be the provenance

Provenance

Provenance, from the French provenir, "to come from", refers to the chronology of the ownership or location of an historical object. The term was originally mostly used for works of art, but is now used in similar senses in a wide range of fields, including science and computing...

of sacred texts, and other matters of faith

Faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person or thing, or a belief that is not based on proof. In religion, faith is a belief in a transcendent reality, a religious teacher, a set of teachings or a Supreme Being. Generally speaking, it is offered as a means by which the truth of the proposition,...

, intellectuals usually propose that such claims be substantiated via external scholarship

Scholarship

A scholarship is an award of financial aid for a student to further education. Scholarships are awarded on various criteria usually reflecting the values and purposes of the donor or founder of the award.-Types:...

. Therefore, a claim about the authenticity of the medieval Shroud of Turin being a religious artifact from antiquity could be scientifically tested; and a theodicy

Theodicy

Theodicy is a theological and philosophical study which attempts to prove God's intrinsic or foundational nature of omnibenevolence , omniscience , and omnipotence . Theodicy is usually concerned with the God of the Abrahamic religions Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, due to the relevant...

could be logic

Logic

In philosophy, Logic is the formal systematic study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Logic is used in most intellectual activities, but is studied primarily in the disciplines of philosophy, mathematics, semantics, and computer science...

ally examined for consistency — although the results might provoke intellectual and existential

Existentialism

Existentialism is a term applied to a school of 19th- and 20th-century philosophers who, despite profound doctrinal differences, shared the belief that philosophical thinking begins with the human subject—not merely the thinking subject, but the acting, feeling, living human individual...

doubt either confirming or negating the faith of the believers. Furthermore, when bohemianism

Bohemianism

Bohemianism is the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people, with few permanent ties, involving musical, artistic or literary pursuits...

, avant-gardism, and romanticism

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

became integral to the fine arts, religious anti-intellectuals perceived them as amoral

Morality

Morality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

, if not immoral — and demanded their censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

. Historically, this remains thematically common to the socio-cultural trends in the Americas and in Europe, since the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

(1517).

Authoritarianism

Dictator

A dictator is a ruler who assumes sole and absolute power but without hereditary ascension such as an absolute monarch. When other states call the head of state of a particular state a dictator, that state is called a dictatorship...

s, and their dictatorship

Dictatorship

A dictatorship is defined as an autocratic form of government in which the government is ruled by an individual, the dictator. It has three possible meanings:...

supporters, use anti-intellectualism to gain popular support, by accusing intellectuals of being a socially detached, politically-dangerous class who question the extant social norms, who dissent from established opinion, and who reject nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, hence they are unpatriotic

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

, and thus subversive of the nation. Violent anti-intellectualism is common to the rise and rule of authoritarian

Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a form of social organization characterized by submission to authority. It is usually opposed to individualism and democracy...

political movements, such as Italian Fascism

Italian Fascism

Italian Fascism also known as Fascism with a capital "F" refers to the original fascist ideology in Italy. This ideology is associated with the National Fascist Party which under Benito Mussolini ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, the Republican Fascist Party which ruled the Italian...

, Stalinism

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

in Russia, Nazism

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

in Germany, the Khmer Rouge

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge literally translated as Red Cambodians was the name given to the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, who were the ruling party in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, led by Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Son Sen and Khieu Samphan...

in Cambodia

Cambodia

Cambodia , officially known as the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia...

, and Iranian theocracy

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution refers to events involving the overthrow of Iran's monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and its replacement with an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the...

.

In the 20th century, intellectuals were systematically demoted or expelled from the power structures, and, occasionally, assassinated

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

. In Argentina in 1966, the military dictatorship

Military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a form of government where in the political power resides with the military. It is similar but not identical to a stratocracy, a state ruled directly by the military....

of Juan Carlos Onganía

Juan Carlos Onganía

Juan Carlos Onganía Carballo was de facto president of Argentina from 29 June 1966 to 8 June 1970. He rose to power as military dictator after toppling, in a coup d’état self-named Revolución Argentina , the democratically elected president Arturo Illia .-Economic and social...

intervened and dislodged many faculties

Faculty (university)

A faculty is a division within a university comprising one subject area, or a number of related subject areas...

, leading to a massive brain drain

Brain drain

Human capital flight, more commonly referred to as "brain drain", is the large-scale emigration of a large group of individuals with technical skills or knowledge. The reasons usually include two aspects which respectively come from countries and individuals...

in an event which was called The Night of the Long Police Batons

La Noche de los Bastones Largos

La Noche de los Bastones Largos was the violent dislodge of five faculties of the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina on July 29, 1966 by the Federal Police...

. The biochemist

Biochemistry

Biochemistry, sometimes called biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes in living organisms, including, but not limited to, living matter. Biochemistry governs all living organisms and living processes...

César Milstein

César Milstein

César Milstein FRS was an Argentine biochemist in the field of antibody research. Milstein shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984 with Niels K. Jerne and Georges Köhler.-Biography:...

reports that when the military usurped Argentine government, they declared: “our country would be put in order, as soon as all the intellectuals who were meddling in the region were expelled”. In Brazil, the educator Paulo Freire

Paulo Freire

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire was a Brazilian educator and influential theorist of critical pedagogy.-Biography:...

was banished for being ignorant, according to the organizers of the coup d’ État of the moment.

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

dictatorships, such as the Khmer Rouge

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge literally translated as Red Cambodians was the name given to the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, who were the ruling party in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, led by Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Son Sen and Khieu Samphan...

regime in Kampuchea (1975–79), killed potential opponents with more than elementary education. In achieving their Year Zero social engineering

Social engineering (political science)

Social engineering is a discipline in political science that refers to efforts to influence popular attitudes and social behaviors on a large scale, whether by governments or private groups. In the political arena, the counterpart of social engineering is political engineering.For various reasons,...

of Cambodia, they assassinated anyone suspected of “involvement in free-market activities”. The suspected Cambodian populace included professionals and almost every educated man and woman, city-dwellers, and people with connections to foreign governments. Doctrinally, the Maoist

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

Khmer Rouge designated the farmers as the true proletariat

Proletariat

The proletariat is a term used to identify a lower social class, usually the working class; a member of such a class is proletarian...

, as the true representatives of the working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

, hence the anti-intellectual purge (cf. Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

Cultural Revolution

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, commonly known as the Cultural Revolution , was a socio-political movement that took place in the People's Republic of China from 1966 through 1976...

, 1966–76).

Governmental anti-intellectualism ranges from closing public libraries

Public library

A public library is a library that is accessible by the public and is generally funded from public sources and operated by civil servants. There are five fundamental characteristics shared by public libraries...

and public schools, to segregating intellectuals in an Ivory Tower

Ivory Tower

The term Ivory Tower originates in the Biblical Song of Solomon , and was later used as an epithet for Mary.From the 19th century it has been used to designate a world or atmosphere where intellectuals engage in pursuits that are disconnected from the practical concerns of everyday life...

ghetto, to official declarations that intellectuals tend to mental illness, thus facilitating psychiatric

Psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study and treatment of mental disorders. These mental disorders include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities...

imprisonment, then scapegoating to divert popular discontent from the dictatorship (vide the USSR

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and Fascist Italy, cf. Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian writer, politician, political philosopher, and linguist. He was a founding member and onetime leader of the Communist Party of Italy and was imprisoned by Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime...

).

Moreover, anti-intellectualism is neither always violent, nor oppressive, because most any social group can exercise contempt for intellect

Intellect

Intellect is a term used in studies of the human mind, and refers to the ability of the mind to come to correct conclusions about what is true or real, and about how to solve problems...

, intellectualism

Intellectualism

Intellectualism denotes the use and development of the intellect, the practice of being an intellectual, and of holding intellectual pursuits in great regard. Moreover, in philosophy, “intellectualism” occasionally is synonymous with “rationalism”, i.e. knowledge derived mostly from reason and...

, and education

Higher education

Higher, post-secondary, tertiary, or third level education refers to the stage of learning that occurs at universities, academies, colleges, seminaries, and institutes of technology...

. To wit, the Uruguay

Uruguay

Uruguay ,officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay,sometimes the Eastern Republic of Uruguay; ) is a country in the southeastern part of South America. It is home to some 3.5 million people, of whom 1.8 million live in the capital Montevideo and its metropolitan area...

an writer Jorge Majfud

Jorge Majfud

-Life:He was born in Tacuarembó, Uruguay. He majored in and in 1996 graduated from the in Montevideo. He travelled extensively to gather material that would later become part of his novels and essays, and was a professor at the of Costa Rica and at , where he taught art and mathematics.In 2003...

said that “this contempt, that arises, from a power installed in the social institutions, and from the inferiority complex of its actors, is not a property of ‘underdeveloped’ countries. In fact, it is always the critical intellectuals, writers, or artists who head the top-ten lists of ‘The Most Stupid of the Stupid’ in the country.”

Populism

Politics — When orthodox democratic politics fail, populismPopulism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

flourishes in the left-wing, the centre, and the right-wing of a nation’s political spectrum — each variety emphasising the virtue

Virtue

Virtue is moral excellence. A virtue is a positive trait or quality subjectively deemed to be morally excellent and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being....

s of the uncorrupt, unsophisticated “salt of the earth” folk against professional politicians and their intellectual

Intellectual

An intellectual is a person who uses intelligence and critical or analytical reasoning in either a professional or a personal capacity.- Terminology and endeavours :"Intellectual" can denote four types of persons:...

helpers, public intellectuals, academics, think tanks.

Some forms of populism portray intellectuals as elitists

Elitism

Elitism is the belief or attitude that some individuals, who form an elite — a select group of people with intellect, wealth, specialized training or experience, or other distinctive attributes — are those whose views on a matter are to be taken the most seriously or carry the most...

possessed of rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

al skills with which they deceive the common folk. In the US, former President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

George W. Bush

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush is an American politician who served as the 43rd President of the United States, from 2001 to 2009. Before that, he was the 46th Governor of Texas, having served from 1995 to 2000....

(2001–09) used populism to regain support for his government; the Washington Post newspaper story “The President as Average Joe: Trying to Boost Support, Bush Brings Banter to the People” (2 April 2006), reported that: “As he takes to the road to salvage his presidency, Bush is letting down his guard and playing up his anti-intellectual, regular-guy image. Where he spent last year [2005] in rehearsed forums with select supporters, these days he is more frequently throwing aside the script and opening himself to questions from audiences that are not prescreened. These sessions have put a sometimes playful, sometimes awkward side back on display after years of trying to keep it under control to appear more presidential.”

Academy

An academy is an institution of higher learning, research, or honorary membership.The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 385 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and skill, north of Athens, Greece. In the western world academia is the...

knowledge must be controlled, by “the people”, because educators must work within the politics of the interested parties, such as the government, nationally, and with parents’ groups, regionally, in establishing the content of the school curriculum

Curriculum

See also Syllabus.In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses, and their content, offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults...

. In the US, the common populist action is religiously-supported education politics to introduce evangelical Protestant Christian religious interpretations of national history and natural science to school curricula — especially creationism

Creationism

Creationism is the religious beliefthat humanity, life, the Earth, and the universe are the creation of a supernatural being, most often referring to the Abrahamic god. As science developed from the 18th century onwards, various views developed which aimed to reconcile science with the Genesis...

, or variant pseudosciences, such as Scientific Creationism

Creation science

Creation Science or scientific creationism is a branch of creationism that attempts to provide scientific support for the Genesis creation narrative in the Book of Genesis and disprove generally accepted scientific facts, theories and scientific paradigms about the history of the Earth, cosmology...

and Intelligent Design

Intelligent design

Intelligent design is the proposition that "certain features of the universe and of living things are best explained by an intelligent cause, not an undirected process such as natural selection." It is a form of creationism and a contemporary adaptation of the traditional teleological argument for...

, as factually-equal counters to evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

. (see: Discovery Institute

Discovery Institute

The Discovery Institute is a non-profit public policy think tank based in Seattle, Washington, best known for its advocacy of intelligent design...

)

Government Policy - In the USSR, in 1948, the Stalinist Central Committee officially imposed the Soviet (national) science of Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism, or Lysenko-Michurinism, also denotes the biological inheritance principle which Trofim Lysenko subscribed to and which derive from theories of the heritability of acquired characteristics, a body of biological inheritance theory which departs from Mendelism and that Lysenko named...

upon agriculture. A concept developed by Agronomist

Agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants for food, fuel, feed, fiber, and reclamation. Agronomy encompasses work in the areas of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and soil science. Agronomy is the application of a combination of sciences like biology,...

Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko was a Soviet agronomist of Ukrainian origin, who was director of Soviet biology under Joseph Stalin. Lysenko rejected Mendelian genetics in favor of the hybridization theories of Russian horticulturist Ivan Vladimirovich Michurin, and adopted them into a powerful...

, Lysenkoism was promoted as the realization of Communist ideology: raised by farming parents and with limited formal education, he was lionized as the creator of innovative crop-growing methods based on the outdated concept of Lamarckian inheritance

Lamarckism

Lamarckism is the idea that an organism can pass on characteristics that it acquired during its lifetime to its offspring . It is named after the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck , who incorporated the action of soft inheritance into his evolutionary theories...

. Soviet government suppressed non-Lysenkoist biology, including the dismissal and assassination of scientists such as Nikolai Vavilov

Nikolai Vavilov

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was a prominent Russian and Soviet botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants...

. Ultimately, Lysenkoism yielded poor agricultural

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

results for the USSR. Moreover, because Lysenkoism was more political than scientific, its fortunes waxed and waned amid Russian Communist Party politics, ending as an officially discredited pseudoscience

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice which is presented as scientific, but which does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested, or otherwise lacks scientific status...

upon the fall of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, in 1964.

Educational anti-intellectualism

EducationEducation

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

is often associated with charges of anti-intellectualism from a variety of critics who disagree over the meaning, goals and curricula

Curriculum

See also Syllabus.In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses, and their content, offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults...

of public education

Public education

State schools, also known in the United States and Canada as public schools,In much of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the terms 'public education', 'public school' and 'independent school' are used for private schools, that is, schools...

. Historically, such intellectual disagreements have manifested as Kulturkampf

Kulturkampf

The German term refers to German policies in relation to secularity and the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, enacted from 1871 to 1878 by the Prime Minister of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck. The Kulturkampf did not extend to the other German states such as Bavaria...

in Bismarck’s Germany and Culture War

Culture war

The culture war in American usage is a metaphor used to claim that political conflict is based on sets of conflicting cultural values. The term frequently implies a conflict between those values considered traditionalist or conservative and those considered progressive or liberal...

s in the contemporary US.

Grammar school

In the 2004 New York Times newspaper article “When Every Child is Good Enough”, John TierneyJohn Tierney (journalist)

John Marion Tierney is a journalist and author who has worked for the New York Times since 1990.-Career and background:...

reported that conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

parents believe that US primary and secondary schools over-emphasize equality of outcome

Equality of outcome

Equality of outcome, equality of condition, or equality of results is a controversial political concept. Although it is not always clearly defined, it is usually taken to describe a state in which people have approximately the same material wealth or, more generally, in which the general conditions...

to the detriment of their children's individual (unequal) achievements. A literary example of that contention is the science fiction

Social science fiction

Social science fiction is a term used to describe a subgenre of science fiction concerned less with technology and space opera and more with sociological speculation about human society...

short story 'Harrison Bergeron

Harrison Bergeron

"Harrison Bergeron" is a satirical, dystopian science fiction short story written by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. and first published in October 1961. Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, the story was re-published in the author's collection Welcome to the Monkey House in...

' (1961), by Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. was a 20th century American writer. His works such as Cat's Cradle , Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions blend satire, gallows humor and science fiction. He was known for his humanist beliefs and was honorary president of the American Humanist Association.-Early...

, wherein the government’s Handicapper General

Harrison Bergeron

"Harrison Bergeron" is a satirical, dystopian science fiction short story written by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. and first published in October 1961. Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, the story was re-published in the author's collection Welcome to the Monkey House in...

imposes equality upon the eponymous hero, lest his existence — as the smartest, handsomest, most athletic boy in the world — hurt the feelings of the mediocre popular

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

majority, (viz. the over-simplification, the dumbing down

Dumbing down

Dumbing down is a pejorative term for a perceived trend to lower the intellectual content of literature, education, news, and other aspects of culture...

, of curricula

Curriculum

See also Syllabus.In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses, and their content, offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults...

).

University

In the English-speaking worldEnglish-speaking world

The English-speaking world consists of those countries or regions that use the English language to one degree or another. For more information, please see:Lists:* List of countries by English-speaking population...

, especially in the US, critics like David Horowitz

David Horowitz

David Joel Horowitz is an American conservative writer and policy advocate. Horowitz was raised by parents who were both members of the American Communist Party. Between 1956 and 1975, Horowitz was an outspoken adherent of the New Left before rejecting Marxism completely...

(viz. the David Horowitz Freedom Center

David Horowitz Freedom Center

The David Horowitz Freedom Center is a conservative foundation founded in 1988 by political activist David Horowitz and his long-time collaborator Peter Collier...

), William Bennett, an ex-US secretary of education, and paleoconservative activist

Paleoconservatism

Paleoconservatism is a term for a conservative political philosophy found primarily in the United States stressing tradition, limited government, civil society, anti-colonialism, anti-corporatism and anti-federalism, along with religious, regional, national and Western identity. Chilton...

Patrick Buchanan, criticize schools and universities as 'intellectualist

Intellectualism

Intellectualism denotes the use and development of the intellect, the practice of being an intellectual, and of holding intellectual pursuits in great regard. Moreover, in philosophy, “intellectualism” occasionally is synonymous with “rationalism”, i.e. knowledge derived mostly from reason and...

' based on three sets of criteria:

- Political bias: That university professors, instructors, and lecturers, inculcate secularSecularismSecularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

values to the students without ‘equal time’ for analogue views. Proponents of such arguments assert that the political bias sacrifices objectivity and traditionTraditionA tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

al religious values in favour of political radicalismPolitical radicalismThe term political radicalism denotes political principles focused on altering social structures through revolutionary means and changing value systems in fundamental ways...

and left-wingLeft-wing politicsIn politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

perspectives, especially in the HumanitiesHumanitiesThe humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytical, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences....

, and in the social sciencesSocial sciencesSocial science is the field of study concerned with society. "Social science" is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to a plurality of fields outside of the natural sciences usually exclusive of the administrative or managerial sciences...

that challenge the cultural validity of whiteWhite peopleWhite people is a term which usually refers to human beings characterized, at least in part, by the light pigmentation of their skin...

patriarchyPatriarchyPatriarchy is a social system in which the role of the male as the primary authority figure is central to social organization, and where fathers hold authority over women, children, and property. It implies the institutions of male rule and privilege, and entails female subordination...

. - Deficient curricula: That there are a lack of general education requirements (i.e. the Humanities) such as philosophyPhilosophyPhilosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, historyHistoryHistory is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

, literatureLiteratureLiterature is the art of written works, and is not bound to published sources...

, musicMusicMusic is an art form whose medium is sound and silence. Its common elements are pitch , rhythm , dynamics, and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture...

, et cetera, especially those emphasizing the contributions of Western civilization, in acquiring a balanced education. - Impracticality: That a humanisticHumanitiesThe humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytical, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences....

education is not readily profitableProfit (economics)In economics, the term profit has two related but distinct meanings. Normal profit represents the total opportunity costs of a venture to an entrepreneur or investor, whilst economic profit In economics, the term profit has two related but distinct meanings. Normal profit represents the total...

in ‘real life’ as opposed to a technicalVocational educationVocational education or vocational education and training is an education that prepares trainees for jobs that are based on manual or practical activities, traditionally non-academic, and totally related to a specific trade, occupation, or vocation...

(computer science, engineering, etc.) or professionalProfessionalA professional is a person who is paid to undertake a specialised set of tasks and to complete them for a fee. The traditional professions were doctors, lawyers, clergymen, and commissioned military officers. Today, the term is applied to estate agents, surveyors , environmental scientists,...

(business, law, medicine, etc.) education.

In his book The Campus Wars about the widespread student protests of the late 1960s, philosopher John Searle

John Searle

John Rogers Searle is an American philosopher and currently the Slusser Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley.-Biography:...

wrote:

- the two most salient traits of the radical movement are its anti-intellectualism and its hostility to the university as an institution. […] Intellectuals by definition are people who take ideas seriously for their own sake. Whether or not a theory is true or false is important to them independently of any practical applications it may have. [Intellectuals] have, as Richard Hofstadter has pointed out, an attitude to ideas that is at once playful and pious. But in the radical movement, the intellectual ideal of knowledge for its own sake is rejected. Knowledge is seen as valuable only as a basis for action, and it is not even very valuable there. Far more important than what one knows is how one feels.

In 1972, sociologist Stanislav Andreski

Stanislav Andreski

Stanisław Andrzejewski was a Polish-British sociologist known best for his scathing indictment of the "pretentious nebulous verbosity" endemic in the modern social sciences in his classic work Social Sciences as Sorcery .Andrzejewski was a Polish Army officer...

warned readers of academic works to be wary of appeals to authority when academics make questionable claims, writing, “do not be impressed by the imprint of a famous publishing house or the volume of an author’s publications. […] Remember that the publishers want to keep the printing presses busy and do not object to nonsense if it can be sold.”

Critics have alleged that much of the prevailing philosophy in American academia (i.e., postmodernism, poststructuralism, relativism) are anti-intellectual: “The displacement of the idea that facts and evidence matter by the idea that everything boils down to subjective interests and perspectives is -- second only to American political campaigns -- the most prominent and pernicious manifestation of anti-intellectualism in our time.”

In the notorious Sokal Hoax of the 1990s, physicist Alan Sokal

Alan Sokal

Alan David Sokal is a professor of mathematics at University College London and professor of physics at New York University. He works in statistical mechanics and combinatorics. To the general public he is best known for his criticism of postmodernism, resulting in the Sokal affair in...

submitted a deliberately preposterous paper to Duke University's Social Texts journal to test if, as he later wrote, a leading "culture studies" periodical would "publish an article liberally salted with nonsense if (a) it sounded good and (b) it flattered the editors' ideological preconceptions." Social Texts published the paper, seemingly without noting any of the paper's abundant mathematical and scientific errors, leading Sokal to declare that "my little experiment demonstrate[s], at the very least, that some fashionable sectors of the American academic Left have been getting intellectually lazy."

In a 1995 interview, social critic Camille Paglia

Camille Paglia

Camille Anna Paglia , is an American author, teacher, and social critic. Paglia, a self-described dissident feminist, has been a Professor at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania since 1984...

described academics (including herself) as "a parasitic class," arguing that during widespread social disruption "the only thing holding this culture together will be masculine men of the working class. The cultural elite--women and men--will be pleading for the plumbers and the construction workers."

Youth culture

Critics have suggested that contemporary youth cultureYouth subculture

A youth subculture is a youth-based subculture with distinct styles, behaviors, and interests. Youth subcultures offer participants an identity outside of that ascribed by social institutions such as family, work, home and school...

is a commercial

Commerce

While business refers to the value-creating activities of an organization for profit, commerce means the whole system of an economy that constitutes an environment for business. The system includes legal, economic, political, social, cultural, and technological systems that are in operation in any...

form of anti-intellectualism orienting adherents to consumerism

Consumerism

Consumerism is a social and economic order that is based on the systematic creation and fostering of a desire to purchase goods and services in ever greater amounts. The term is often associated with criticisms of consumption starting with Thorstein Veblen...

. The Frontline public affairs television series documentary The Merchants of Cool(2001) describes how the advertising

Advertising

Advertising is a form of communication used to persuade an audience to take some action with respect to products, ideas, or services. Most commonly, the desired result is to drive consumer behavior with respect to a commercial offering, although political and ideological advertising is also common...

business transformed adolescents’

Adolescence

Adolescence is a transitional stage of physical and mental human development generally occurring between puberty and legal adulthood , but largely characterized as beginning and ending with the teenage stage...

language, thought, and action (clique

Clique

A clique is an exclusive group of people who share common interests, views, purposes, patterns of behavior, or ethnicity. A clique as a reference group can be either normative or comparative. Membership in a clique is typically exclusive, and qualifications for membership may be social or...

s, fashion

Fashion

Fashion, a general term for a currently popular style or practice, especially in clothing, foot wear, or accessories. Fashion references to anything that is the current trend in look and dress up of a person...

, fads) into commodities

Commodity

In economics, a commodity is the generic term for any marketable item produced to satisfy wants or needs. Economic commodities comprise goods and services....

, and thus engendered a generation

Generation

Generation , also known as procreation in biological sciences, is the act of producing offspring....

of intellectually disengaged Americans uninterested in progressing to adulthood.

The US youth subculture

Subculture

In sociology, anthropology and cultural studies, a subculture is a group of people with a culture which differentiates them from the larger culture to which they belong.- Definition :...

originated from the post-World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

economic prosperity allowing adolescents to work and have a discretionary income — whilst still dependent upon parents. In turn, scholars argue that the newfound economic power of adolescents allowed business to sell them popularity

Popularity

Popularity is the quality of being well-liked or common, or having a high social status. Popularity figures are an important part of many people's personal value systems and form a vital component of success in people-oriented fields such as management, politics, and entertainment, among...

— an identity

Identity (social science)

Identity is a term used to describe a person's conception and expression of their individuality or group affiliations . The term is used more specifically in psychology and sociology, and is given a great deal of attention in social psychology...

as a young person — something that once was not for sale, but self-created; to wit, the British blog

Blog

A blog is a type of website or part of a website supposed to be updated with new content from time to time. Blogs are usually maintained by an individual with regular entries of commentary, descriptions of events, or other material such as graphics or video. Entries are commonly displayed in...

writer Paul Graham likened youth culture to an occupation permitting little time for education and intellectual interests.

American anti-intellectualism

17th Century

In The Powring Out of the Seven Vials (1642), the PuritanPuritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

John Cotton wrote that ‘the more learned and witty you bee, the more fit to act for Satan

Satan

Satan , "the opposer", is the title of various entities, both human and divine, who challenge the faith of humans in the Hebrew Bible...

will you bee. . . . Take off the fond doting . . . upon the learning of the Jesuites

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

, and the glorie of the Episcopacy, and the brave estates of the Prelates. I say bee not deceived by these pompes, empty shewes, and faire representations of goodly condition before the eyes of flesh and blood, bee not taken with the applause of these persons.’ Not every Puritan concurred with Cotton's contempt for secular

Secularism

Secularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

education; some founded universities such as Harvard

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

, Yale

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

, and Dartmouth

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College is a private, Ivy League university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. The institution comprises a liberal arts college, Dartmouth Medical School, Thayer School of Engineering, and the Tuck School of Business, as well as 19 graduate programs in the arts and sciences...

.

Economist Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell is an American economist, social theorist, political philosopher, and author. A National Humanities Medal winner, he advocates laissez-faire economics and writes from a libertarian perspective...

argues that American anti-intellectualism can be traced to the early Colonial era, and that wariness of the educated upper-classes is understandable given that America was built, in large part, by people fleeing persecution and brutality at the hands of the educated upper classes. Additionally, rather few intellectuals possessed the practical hands-on skills required to survive in the New World, leading to a deeply-rooted suspicion of those who may appear to specialize in "verbal virtuosity" rather than tangible, measurable products or services:

- From its colonial beginnings, American society was a “decapitated” society—largely lacking the topmost social layers of European society. The highest elites and the titled aristocracies had little reason to risk their lives crossing the Atlantic and then face the perils of pioneering. Most of the white population of colonial America arrived as indentured servantIndentured servantIndentured servitude refers to the historical practice of contracting to work for a fixed period of time, typically three to seven years, in exchange for transportation, food, clothing, lodging and other necessities during the term of indenture. Usually the father made the arrangements and signed...

s and the black population as slaves. Later waves of immigrants were disproportionately peasantPeasantA peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

s and proletarians, even when they came from Western Europe [...] The rise of American society to pre-eminence as an economic, political and military power was thus the triumph of the common man and a slap across the face to the presumptions of the arrogant, whether an elite of blood or books.

19th Century

In the history of American anti-intellectualism, modern scholars suggest that 19th century popular culturePopular culture

Popular culture is the totality of ideas, perspectives, attitudes, memes, images and other phenomena that are deemed preferred per an informal consensus within the mainstream of a given culture, especially Western culture of the early to mid 20th century and the emerging global mainstream of the...

is important, because, when most of the populace lived a rural

Rural

Rural areas or the country or countryside are areas that are not urbanized, though when large areas are described, country towns and smaller cities will be included. They have a low population density, and typically much of the land is devoted to agriculture...

life of manual labour

Manual labour

Manual labour , manual or manual work is physical work done by people, most especially in contrast to that done by machines, and also to that done by working animals...

and agricultural

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

work, a ‘bookish’ education, concerned with the Græco-Roman classics

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

, was perceived as of impractical value, ergo unprofitable

Profit (economics)

In economics, the term profit has two related but distinct meanings. Normal profit represents the total opportunity costs of a venture to an entrepreneur or investor, whilst economic profit In economics, the term profit has two related but distinct meanings. Normal profit represents the total...

— yet Americans, generally, were literate

Literacy

Literacy has traditionally been described as the ability to read for knowledge, write coherently and think critically about printed material.Literacy represents the lifelong, intellectual process of gaining meaning from print...

and read Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

for pleasure — thus, the ideal

Idealism

In philosophy, idealism is the family of views which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally mental, mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial. Epistemologically, idealism manifests as a skepticism about the possibility of knowing any mind-independent thing...

"American" man was technically skilled and successful in his trade

Trade

Trade is the transfer of ownership of goods and services from one person or entity to another. Trade is sometimes loosely called commerce or financial transaction or barter. A network that allows trade is called a market. The original form of trade was barter, the direct exchange of goods and...

, ergo a productive member of society. Culturally, the ideal American was a self-made man whose knowledge derived from life-experience, not an intellectual man, whose knowledge derived from books, formal education, and academic study; thus, in The New Purchase, or Seven and a Half Years in the Far West (1843), the Reverend Bayard R. Hall, A.M., said about frontier Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

:

“We always preferred an ignorant bad man to a talented one, and, hence, attempts were usually made to ruin the moralMoralityMorality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

character of a smart candidate; since, unhappily, smartnessIntellectual giftednessIntellectual giftedness is an intellectual ability significantly higher than average. It is different from a skill, in that skills are learned or acquired behaviors...

and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and [like-wise] incompetence and goodness."

Yet, the egghead

Egghead

In the slang of the United States, egghead is an anti-intellectual epithet, directed at people considered too out-of-touch with ordinary people and too lacking in realism, common sense, virility, etc. on account of their intellectual interests. The British equivalent is boffin...

's worldly redemption was possible if he embraced mainstream

Mainstream

Mainstream is, generally, the common current thought of the majority. However, the mainstream is far from cohesive; rather the concept is often considered a cultural construct....

mores

Mores

Mores, in sociology, are any given society's particular norms, virtues, or values. The word mores is a plurale tantum term borrowed from Latin, which has been used in the English language since the 1890s....

; thus, in the fiction of O. Henry

O. Henry

O. Henry was the pen name of the American writer William Sydney Porter . O. Henry's short stories are well known for their wit, wordplay, warm characterization and clever twist endings.-Early life:...

, a character noted that once an East Coast university

University

A university is an institution of higher education and research, which grants academic degrees in a variety of subjects. A university is an organisation that provides both undergraduate education and postgraduate education...

graduate ‘gets over’ his intellectual vanity — no longer thinks himself better than others — he makes just as good a cowboy

Cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the vaquero traditions of northern Mexico and became a figure of...

as any other young man, despite his counterpart being the slow-witted naïf of good heart, a pop culture stereotype

Stereotype

A stereotype is a popular belief about specific social groups or types of individuals. The concepts of "stereotype" and "prejudice" are often confused with many other different meanings...

from stage shows.

20th and 21st centuries

Charges of anti-intellectualism have been made against a variety of movements and schools of thought:- Anti-war protests — The 1960s–70s anti-war movement protesting the ten-year US–Vietnam WarVietnam WarThe Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

(1963–1973), demonstrated its anti-intellectual leanings against US defence secretary Robert McNamaraRobert McNamaraRobert Strange McNamara was an American business executive and the eighth Secretary of Defense, serving under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 to 1968, during which time he played a large role in escalating the United States involvement in the Vietnam War...

. They rallied against the war's increasing casualties, and the intellectual justification for the war, which was becoming seemingly impossible to win. McNamara's appearance as an intellectual, justifying warfare with an apparent disregard for the lives of American soldiers had become very unpopular. The anti-intellectualism in this movement may have been a counter to the perceived 'intellectual' rationalisation of the war by McNamara and others.

- Marxist intellectual Theodor Adorno criticised such left-wing anti-intellectualism as "actionism," a kind of ineffective "pseudo-activity" which serves to deflect attention from the difficulty of genuinely changing the world, a difficulty which critical thought would make clear.

- However, publications such as The Pentagon Papers (1971) had made the war very unpopular with intellectuals and anti-intellectuals alike, and the movement gained much popular support, cumulating in the Case Church Amendment and the eventual exit of American troops from the war in 1973.