Vichy France

Encyclopedia

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers

from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic

and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic

. It officially called itself the French State (État Français), in contrast with the previous designation, the French Republic.

Marshal

Philippe Pétain

proclaimed the government following the military defeat of France

by Germany

during World War II and the vote by the National Assembly

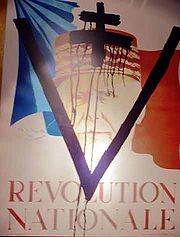

on 10 July 1940. This vote granted extraordinary powers to Pétain, the last Président du Conseil (Prime Minister) of the Third Republic, who then took the additional title Chef de l'État Français ("Chief of the French State"). Pétain headed the reactionary

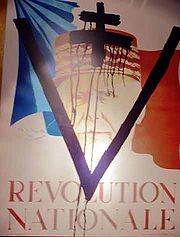

program of the so-called "Révolution nationale

", aimed at "regenerating the nation."

The Vichy regime maintained some legal authority in the northern zone of France (the Zone occupée

), which was occupied by the German Wehrmacht

. Its laws, however, were only applied where they did not contradict German ones. This meant that the regime was most powerful in the unoccupied southern "free zone

", where its administrative centre of Vichy

was located, until November 1942. After the landing of the Allied forces in North Africa

on 8 November 1942, Hitler ordered the occupation of France's free zone

, after which the former free zone was subject to German rule like the northern zone, except for a sliver along the Alps that was under Italian rule until September 1943.

In the aftermath of the 1940 defeat, Pétain collaborated

with the German occupying forces in exchange for an agreement to not divide France between the Axis Powers. Vichy forces refused to surrender or save the fleet at Mers-el-Kebir for the Allies and fought the Allied invasion of French-controlled Syria and Lebanon in June–July 1941

, with just above 15% of the resulting prisoners of war electing to join Free French forces

while the others were repatriated to metropolitan France to be demobilized. However, the military ties with Germany weakened over time. The Vichy-mandated scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon

stands in contrast to the Mers-el-Kebir episode of two years earlier, and the Vichy French forces put up limited resistance to the Allied invasion of North Africa

, with more commanders and units in Africa joining the Free French forces. The Vichy leaders collaborated as far as ordering the French police and the local milice

(militiamen) to go on raids to capture Jews and other minorities considered "undesirables" by Germany as well as political opponents and members of the Resistance

, thus helping enforce German policy in occupied zones. Vichy also promulgated its own, German-inspired laws and policies that restricted political freedom and took rights away from foreigners and racial minorities.

The legitimacy of Vichy France and Pétain's leadership was constantly challenged by the exiled General Charles de Gaulle

, who claimed to represent the legitimacy and continuity of the French government. Public opinion turned against the Vichy regime and the occupying German forces over time, and resistance to them

grew within France. Following the Allies' invasion of France in Operation Overlord

, de Gaulle proclaimed the Provisional Government of the French Republic

(GPRF) in June 1944. After the Liberation of Paris

in August, the GPRF installed itself in Paris on 31 August. The GPRF was recognized as the legitimate government of France by the Allies on 23 October 1944.

On 20 August 1944, the Vichy officials and chief supporters were moved to Sigmaringen

in Germany and there established a government in exile

, headed by Fernand de Brinon

, until early April 1945. Most of the Vichy regime's leaders were subsequently sentenced by the GPRF and a number of them were executed. Pétain himself was sentenced to death for treason, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

In 1940, Marshal Pétain was known mainly as a World War I hero, the victor of Verdun

. As last Prime Minister

of the Third Republic, Pétain, a reactionary by inclination, blamed the Third Republic's democracy for France's quick defeat. He set up a paternalistic, semi-fascist regime that actively collaborated with Germany, its official neutrality notwithstanding. Vichy even cooperated with the Nazis' racial policies

.

It is a common misconception that the Vichy Regime administered only the unoccupied zone of southern France (named "free zone" (zone libre) by Vichy), while the Germans directly administered the occupied zone. In fact, the civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over the whole of metropolitan France

It is a common misconception that the Vichy Regime administered only the unoccupied zone of southern France (named "free zone" (zone libre) by Vichy), while the Germans directly administered the occupied zone. In fact, the civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over the whole of metropolitan France

, except for Alsace-Lorraine

, a disputed territory which was placed under German administration (though not formally annexed). French civil servants in Bordeaux

, such as Maurice Papon

; or Nantes

, were under the authority of French ministers in Vichy. René Bousquet

, head of French police nominated by Vichy, exercised his power directly in Paris through his second-in-command, Jean Leguay

, who coordinated raids with the Nazis. German laws, however, took precedence over French ones in the occupied territories and the Germans often rode roughshod over the sensibilities of Vichy administrators.

On 11 November 1942, the Germans launched Operation Case Anton

, occupying southern France, following the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch

). Although Vichy's "Armistice Army" was disbanded, thus diminishing Vichy's independence, the abolition of the line of demarcation in March 1943 made civil administration easier. Vichy continued to exercise jurisdiction over almost all of France until the collapse of the regime following the Allied invasion in June 1944.

Until 23 October 1944, the Vichy Regime was acknowledged as the official government of France by the United States and other countries, including Canada, which were at the same time at war with Germany. The United Kingdom maintained unofficial contacts with Vichy, at least until it became apparent that the Vichy Prime Minister, Pierre Laval

, intended full collaboration with the Germans. Even after that it maintained an ambivalent attitude towards the alternative Free French

movement and future government.

The Vichy government's claim that it was the de jure

French government was challenged by the Free French Forces of Charles de Gaulle (based first in London and later in Algiers

) and subsequent French governments. They have continuously held that the Vichy Regime was an illegal government run by traitors

. Historians in particular have debated the circumstances of the vote of full powers to Pétain on 10 July 1940. The main arguments advanced against Vichy's right to incarnate the continuity of the French State were based on the pressure exerted by Laval on deputies in Vichy, and on the absence of 27 deputies and senators who had fled on the ship Massilia

and could thus not take part in the vote.

, drawn mainly, though not exclusively, from the Communist and Republican elements of society against the reactionary

elements who desired a fascist or similar regime as in Francisco Franco

's Spain. This civil war can be seen as the continuation of a division existing within French society since the 1789 French Revolution

, illustrated by events such as:

A part of French society had never accepted the republican regime issuing from the Revolution, and wished to re-establish the Ancien Régime. This was made apparent by the glee of the leader of the monarchist Action Française

, Charles Maurras

, who qualified the suppression of the French Republic as a "divine surprise".

on 10 May 1940. Within days, it became clear that French forces were overwhelmed and that military collapse was imminent. Government and military leaders, deeply shocked by the debacle, debated how to proceed. Many officials, including Prime Minister Paul Reynaud

, wanted to move the government to French territories in North Africa, and continue the war with the French Navy and colonial resources. Others, particularly the Vice-Premier Philippe Pétain and the Commander-in-Chief, General Maxime Weygand

, insisted that the responsibility of the government was to remain in France and share the misfortune of its people. The latter view called for an immediate cessation of hostilities.

While this debate continued, the government was forced to relocate several times, finally reaching Bordeaux, in order to avoid capture by advancing German forces. Communications were poor and thousands of civilian refugees clogged the roads. In these chaotic conditions, advocates of an armistice gained the upper hand. The Cabinet agreed on a proposal to seek armistice terms from Germany, with the understanding that, should Germany set forth dishonourable or excessively harsh terms, France would retain the option to continue to fight. General Charles Huntziger

, who headed the French armistice delegation, was told to break off negotiations if the Germans demanded the occupation of all metropolitan France, the French fleet or any of the French overseas territories. They did not.

was in favour of continuing the war, from North Africa if necessary. He was soon, however, outvoted by those who advocated surrender. Facing an untenable situation, Reynaud resigned and, on his recommendation, President Albert Lebrun

appointed the 84-year-old Pétain to replace him on 16 June. The Armistice with France (Second Compiègne)

agreement was signed on 22 June. A separate agreement was reached with Italy, which had entered the war against France on 10 June, well after the outcome of the battle was beyond doubt, and whose forces had been easily pushed back by the French.

Adolf Hitler

was motivated by a number of reasons to agree to the armistice. He feared that France would continue to fight from North Africa, and he wanted to ensure that the French Navy was taken out of the war. In addition, leaving a French government in place would relieve Germany of the considerable burden of administering French territory. Finally, he hoped to direct his attentions toward Britain, where he anticipated another quick victory.

who were transferred to Germany at the end of 1940 would remain in captivity during the German occupation. In addition, the French had to pay the occupation costs for the 300,000 strong German occupation army. The costs amounted to 20 million Reichmarks per day. The French had to pay at the artificial rate of twenty francs to the Mark. This was 50 times the actual costs of the occupation garrison. The French government also had the responsibility for preventing any French people from going into exile.

In southern France, the French were allowed an army. Article IV of the Armistice allowed for a small French army

to be kept in the unoccupied zone, the Army of the Armistice (Armée de l'Armistice). The article also allowed for the military provision of the French colonial empire

overseas. The function of these forces was to keep internal order and to defend French territories from Allied

assault. The French forces were to remain under the overall direction of the German armed forces.

The exact strength of the Vichy French Metropolitan Army was set at 3,768 officers, 15,072 non-commissioned officers, and 75,360 men. All Vichy French forces had to be volunteers. In addition to the army, the size of the Gendarmerie

was fixed at 60,000 men plus an anti-aircraft force of 10,000 men. Despite the influx of trained soldiers from the colonial forces (reduced in size in accordance with the Armistice), there was a shortage of volunteers. As a result, 30,000 men of the "class of 1939" were retained to fill the quota. At the beginning of 1942, these conscripts were released, but there still was an insufficient number of men. This shortage was to remain until the dissolution, despite Vichy appeals to the Germans for a regular form of conscription.

The Vichy French Metropolitan Army was deprived of tanks and other armored vehicles. The army was also desperately short of motorized transport. This was a special problem in the cavalry units which were supposed to be motorized. Surviving recruiting posters for the Army of the Armistice stress the opportunities for athletic activities, including horsemanship. This partially reflects the general emphasis placed by the Vichy regime on rural virtues and outdoor activities, and partially the realities of service in a small and technologically backward military force. Traditional features characteristic of the pre-1940 French Army, such as kepi

s and heavy capotes (buttoned back greatcoats), were replaced by beret

s and simplified uniforms.

The Army of the Armistice was not used against resistance groups active in the south of France, leaving this role to the Vichy Milice

(militia). Members of the regular army were therefore able to defect in significant numbers to the Maquis

, following the German occupation of southern France and the disbandment of the Army of the Armistice in November 1942. By contrast the Milice continued to collaborate and were subject to reprisals after the Liberation.

The Vichy French colonial forces were reduced in accordance with the Armistice. Still, in the Mediterranean area alone, the Vichy French had nearly 150,000 men in arms. There were approximately 55,000 men in the Protectorate of Morocco, approximately 50,000 men in French Algeria

, and almost 40,000 men in the "Army of the Levant

" (Armée du Levant) in the Mandate of Lebanon and the Mandate of Syria. The colonial forces were allowed some armored vehicles. However, these tended to be "vintage" tanks as old as the World War I-era Renault FT.

started convincing the representatives of the French people

, both Senators and Deputies, to vote full powers

to Pétain. They used every means available: promising some ministerial posts, threatening and intimidating others. The charismatic figures who could have opposed Laval, Georges Mandel

, Édouard Daladier

, etc., were on board the ship Massilia, headed for North Africa. On 10 July 1940 the National Assembly, composed of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, voted by 569 votes to 80 (known as the Vichy 80

, including 62 Radicals and Socialists), and 30 voluntary abstention

s, to grant full and extraordinary powers to Marshal Pétain. By the same vote, they also granted him the power to write a new constitution.

The legality of this vote has been contested by the majority of French historians and by all French governments after the war. Three main arguments are put forward:

Partisans of the Vichy claim, on the contrary, point out that the revision was voted by the two chambers (the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies), in conformity with the law. Deputies and senators who voted to grant full powers to Pétain on this day were condemned on an individual basis after the liberation.

The argument concerning the abrogation of procedure is grounded on the absence and on the non-voluntary abstentions of 176 representatives of the people (the 27 on board the Massilia, and additional 92 deputies and 57 senators some of whom were in Vichy, but not present for the vote). In total, the parliament was composed of 846 members, 544 deputies and 302 senators. One senator and 26 deputies were on the Massilia. One senator did not vote. 8 senators and 12 MPs voluntarily abstained. 57 senators and 92 MPs abstained involuntarily. Thus, out of a total of 544 deputies, only 414 voted; and out of a total of 302 senators, only 235 voted. 357 deputies voted in favor of Pétain, and 57 refused to grant him full powers. 212 senators also voted for Pétain, while 23 voted against. The dubious conditions of this vote thus explain why a majority of French historians refuse to consider Vichy as a complete continuity of the French state, notwithstanding the fact that although Pétain could claim for himself legality (and a dubious legitimacy), de Gaulle, as the Gaullist

myth would later make clear, incarnated the real legitimacy. The debate is thus not only of legitimacy versus legality (indeed, by this fact alone, Charles de Gaulle's claim to hold legitimacy ignores the interior resistance). But it rather concerns the illegal circumstances of this vote.

The text voted by the Congress stated:

The Constitutional Acts of 11 and 12 July 1940 granted to Pétain all powers (legislative, judicial, administrative, executive – and diplomatic) and the title of "head of the French state" (chef de l'État français), as well as the right to nominate his successor. On 12 July Pétain designated Pierre Laval

The Constitutional Acts of 11 and 12 July 1940 granted to Pétain all powers (legislative, judicial, administrative, executive – and diplomatic) and the title of "head of the French state" (chef de l'État français), as well as the right to nominate his successor. On 12 July Pétain designated Pierre Laval

as Vice-President and his designated successor, and appointed Fernand de Brinon

as representative to the German High Command in Paris. Pétain remained the head of the Vichy regime until 20 August 1944. The French national motto, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité

(Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood), was replaced by Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Fatherland); it was noted at the time that TFP also stood for the criminal punishment of "travaux forcés à perpetuité" ("forced labor in perpetuity"). Paul Reynaud, who had not officially resigned as Prime Minister, was arrested in September 1940 by the Vichy government and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1941 before the opening of the Riom Trial

.

Pétain was authoritarian by nature, his status as a hero of the Third Republic notwithstanding. Almost as soon as he was granted full powers, he began blaming the Third Republic's democracy for France's humiliating defeat. Accordingly, his regime soon began taking on authoritarian--and in some respects, unmistakably fascist--characteristics. Democratic liberties and guarantees were immediately suspended. The crime of "felony of opinion" (délit d'opinion, i.e. repeal of freedom of thought

and of expression), etc.) was reestablished, and critics were frequently interned

. Elective bodies were replaced by nominated ones. The "municipalities" and the departmental commissions were thus placed under the authority of the administration and of the prefects (nominated by and dependent on the executive power). In January 1941 the National Council (Conseil National), composed of notables from the countryside and the provinces, was instituted under the same conditions.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union recognized the new regime, despite Charles de Gaulle's attempts, in London, to oppose this decision. So too did Canada and Australia. Only the German occupation of all of France in November 1942 ended this diplomatic recognition.

Historians distinguish between a state collaboration followed by the regime of Vichy, and "collaborationists", which usually refer to the French citizens eager to collaborate with Germany and who pushed towards a radicalization of the regime. "Pétainistes", on the other hand, refers to French people who supported Marshal Pétain, without being too keen on collaboration with Germany (although accepting Pétain's state collaboration). State collaboration was illustrated by the Montoire (Loir-et-Cher

Historians distinguish between a state collaboration followed by the regime of Vichy, and "collaborationists", which usually refer to the French citizens eager to collaborate with Germany and who pushed towards a radicalization of the regime. "Pétainistes", on the other hand, refers to French people who supported Marshal Pétain, without being too keen on collaboration with Germany (although accepting Pétain's state collaboration). State collaboration was illustrated by the Montoire (Loir-et-Cher

) interview in Hitler's train on 24 October 1940, during which Pétain and Hitler shook hands and agreed on this cooperation between the two states. Organized by Laval, a strong proponent of collaboration, the interview and the handshake were photographed, and Nazi propaganda

made strong use of this photo to gain support from the civilian population. On 30 October 1940, Pétain officialized state collaboration, declaring on the radio: "I enter today on the path of collaboration...." On 22 June 1942 Laval declared that he was "hoping for the victory of Germany." The sincere desire to collaborate did not stop the Vichy government from organising the arrest and even sometimes the execution of German spies entering the Vichy zone, as Simon Kitson

's recent research has demonstrated.

The composition of the Vichy cabinet, and its policies, were mixed. Many Vichy officials such as Pétain, though not all, were reactionaries

who considered that France's unfortunate fate was a kind of divine punishment for its republican character and the actions of its left-wing governments of the 1930s, in particular of the Popular Front

(1936–1938) led by Léon Blum

. Charles Maurras

, a monarchist writer and founder of the Action Française

movement, judged that Pétain's accession to power was, in that respect, a "divine surprise"; and many people of the same political persuasion judged that it was preferable to have an authoritarian government similar to that of Francisco Franco

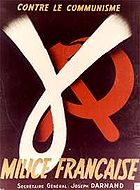

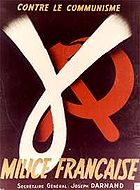

's Spain, albeit under Germany's yoke, than have a republican government. Others, like Joseph Darnand

, were strong anti-Semites

and overt Nazi

sympathizers. A number of these joined the Légion des Volontaires Français contre le Bolchévisme (Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

) units fighting on the Eastern Front

, which later became the SS Charlemagne Division

.

On the other hand, technocrat

s such as Jean Bichelonne

or engineers from the Groupe X-Crise

used their position to push various state, administrative and economic reforms. These reforms would be one of the strongest elements arguing in favor of the thesis of a continuity of the French administration before and after the war. Many of these civil servants remained in function after the war, or were quickly reestablished in their functions after a short-term moment during which they were set aside, while much of these reforms were retained and reinforced after the war. In the same way as the necessities of war economy

during the first World War I had pushed toward state measures which organized the economy of France

against the prevailing classical liberal

theories, an organization which was retained after the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

, reforms adopted during World War II were kept and extended. Along with the 15 March 1944 Charter of the Conseil National de la Résistance

(CNR), which gathered all Resistant movements under one unified political body, these reforms were a main instrument in the establishment of post-war dirigisme

, a kind of semi-planned economy which made of France the modern social democracy

it is now. Examples of such continuities include the creation of the "French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems" by Alexis Carrel

, a renowned physician who also supported eugenics

. This institution would be renamed after the war National Institute of Demographic Studies

(INED) and exists to this day. Another example is the creation of the national statistics institute, renamed INSEE

after the Liberation. The reorganization and unification of the French police by René Bousquet

, who created the groupes mobiles de réserve (GMR, Reserve Mobile Groups), a police force charged with striking fear amid the civilian population is another example of a policy of reform and restructuring deployed to poor purpose under the Vichy administration. Starting in the autumn of 1943, the GMR were used in lower-intensity (if still vicious) actions against the Resistants

in the maquis

, though the primary forces for major fighting missions were the German military and, secondarily and ahead of the GMR, the Franc-garde branch of the Milice

. After the war the GMR would be integrated into the French army and police forces, like other remaining army and police forces (except those that actively fought the Free French Army

). As such elements were merged with the Free French Forces

, jointly renamed Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité

(CRS, Republican Security Companies) in 1944, and became part of the largest anti-riot force in France.

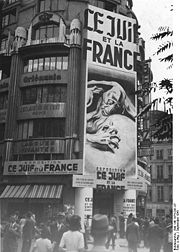

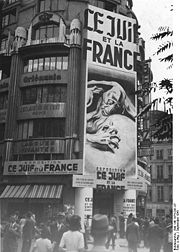

As soon as it had been established, Pétain's government took measures against the so-called "undesirables": Jews

, métèques

(immigrants from Mediterranean countries), Freemasons

, Communists – this was inspired by Charles Maurras

' conception of the "Anti-France", or "internal foreigners", which Maurras defined as the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners"—but also Gypsies, homosexuals, and also, any left-wing activist. Vichy imitated the racial policies of the Third Reich and also engaged in natalist

policies aimed at reviving the "French race", although these policies never went as far as the eugenics program implemented by the Nazi

s.

As soon as July 1940, Vichy set up a special Commission charged of reviewing the naturalization

s granted since the 1927 reform of the nationality law

. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalized. This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment.

The internment camps already opened by the Third Republic were immediately put to a new use, before ultimately inserting themselves as necessary transit camps for the implementation of the Holocaust

and the extermination of all "undesirables", including the Roma people who refer to the extermination of Gypsies as Porrajmos. The October 4th 1940 law authorized internments of foreign Jews on the sole basis of a prefectoral order, and the first raids took place in May 1941. Vichy imposed no restrictions upon black people in the Unoccupied Zone; the regime even had a black cabinet minister, the Martinique lawyer Henry Lemery

.

The Third Republic had opened various concentration camps, first used during World War I to intern enemy alien

s. Camp Gurs

, for example, had been set up in the south-western part of France after the fall of Spanish Catalonia

, in the first months of 1939, during the Spanish Civil War

(1936–1939), to receive the Republican refugees, including Brigadists

from all nations, fleeing the Francists. But as soon as Édouard Daladier

's government (April 1938 – March 1940) took the decision to outlaw the French Communist Party

(PCF) following the German-Soviet non-aggression pact

(aka Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) signed in August 1939, these camps were also used to intern French communists. Drancy internment camp

was founded in 1939 for this use. It later became the central transit camp through which all deportees passed before heading to the concentration and extermination camps in the Third Reich and in Eastern Europe. Furthermore, when the Phoney War started with France's declaration of war against Germany on 3 September 1939, these camps were used to intern enemy aliens. These included German Jews and anti-fascists, but any German citizen (or Italian, Austrian, Polish, etc.) would also be interned in Camp Gurs and others. Common-law prisoners were also evacuated from the prisons in the north of France, before the advance of the Wehrmacht, and interned in these camps. Camp Gurs then received its first contingent of political prisoner

s in June 1940, which included left-wing activists (communists, anarchists

, trade-unionists, anti-militarists, etc.), pacifists, but also French fascists who supported the victory of Italy

and Germany. Finally, after Pétain's proclamation of the "French state" and the beginning of the implementation of the "Révolution nationale

" ("National Revolution"), the French administration opened up many concentration camps, to the point that historian Maurice Rajsfus wrote: "The quick opening of new camps created employment, and the Gendarmerie

never ceased to hire during this period."

Besides the political prisoners already detained there, Gurs was then used to intern foreign Jews, stateless persons, Gypsies, homosexuals, and prostitutes. Vichy opened its first internment camp in the northern zone on 5 October 1940, in Aincourt

, in the Seine-et-Oise

department, which it quickly filled with PCF members. The Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans

, in the Doubs, was used to intern Gypsies. The Camp des Milles

, near Aix-en-Provence

, was the largest internment camp in the Southeast of France. 2,500 Jews were deported from there following the August 1942 raids Spaniards were then deported, and 5,000 of them died in Mauthausen concentration camp. In contrast, the French colonial soldiers were interned by the Germans on French territory instead of being deported.

Besides the concentration camps opened by Vichy, the Germans also opened on French territory some Ilag

s (Internierungslager) to detain enemy aliens, and in Alsace, which had been annexed by the Reich, they opened the camp of Natzweiler, which is the only concentration camp created by Nazis on French territory (annexed by the Third Reich). Natzweiler included a gas chamber

which was used to exterminate at least 86 detainees (mostly Jewish) with the aim obtaining a collection of undamaged skeletons (as this mode of execution did no damage to the skeletons themselves) for the use of Nazi professor August Hirt

.

Furthermore, Vichy enacted a number of racist laws. In August 1940, laws against antisemitism in the media (the Marchandeau Act) were repealed, while the decree

n°1775 September 5, 1943, denaturalized a number of French citizens, in particular Jews from Eastern Europe. Foreigners were rounded-up in "Foreign Workers Groups" (groupements de travailleurs étrangers) and, as the colonial troops, were used by the Germans as manpower. The Statute on Jews

excluded them from the civil administration.

Vichy also enacted a number of racist laws in its French territories in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia).

"The history of the Holocaust in France's three North African colonies (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) is intrinsically tied to France's fate during this period."

With regard to economic contribution to the German economy it is estimated that France provided 42% of the total foreign aid.

winner Alexis Carrel

, who had been an early proponent of eugenics

and euthanasia

and was a member of Jacques Doriot

's French Popular Party (PPF), went on to advocate for the creation of the Fondation Française pour l'Étude des Problèmes Humains (French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems), using connections to the Pétain cabinet (specifically, French industrial physicians André Gros and Jacques Ménétrier). Charged with the "study, in all of its aspects, of measures aimed at safeguarding, improving and developing the French population

in all of its activities", the Foundation was created by decree

of the collaborationist Vichy regime in 1941, and Carrel appointed as 'regent'. The Foundation also had for some time as general secretary François Perroux

.

The Foundation was behind the origin of the 16 December 1942 Act inventing the "prenuptial certificate", which had to precede any marriage and was supposed, after a biological examination, to insure the "good health" of the spouses, in particular in regard to sexually transmitted disease

s (STD) and "life hygiene" (sic). Carrel's institute also conceived the "scholar booklet" ("livret scolaire"), which could be used to record students' grades in the French secondary schools

, and thus classify and select them according to scholastic performance. Beside these eugenics activities aimed at classifying the population and "improving" its "health", the Foundation also supported the 11 October 1946 law instituting occupational medicine, enacted by the Provisional Government of the French Republic

(GPRF) after the Liberation.

The Foundation also initiated studies on demographics (Robert Gessain, Paul Vincent, Jean Bourgeois), nutrition (Jean Sutter), lodging (Jean Merlet) as well as the first polls (Jean Stoetzel). The foundation, which after the war became the INED demographics

institute, employed 300 researchers from the summer of 1942 to the end of the autumn of 1944. "The foundation was chartered as a public institution under the joint supervision of the ministries of finance and public health. It was given financial autonomy and a budget of forty million francs, roughly one franc per inhabitant: a true luxury considering the burdens imposed by the German Occupation on the nation's resources. By way of comparison, the whole Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique

(CNRS) was given a budget of fifty million francs."

Alexis Carrel had previously published in 1935 the best-selling book titled L'Homme, cet inconnu ("Man, This Unknown"). Since the early 1930s, Alexis Carrel advocated the use of gas chambers

to rid humanity of its "inferior stock", endorsing the scientific racism

discourse. One of the founder of these pseudoscientifical

theories had been Arthur de Gobineau

in his 1853–1855 essay titled An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races

. In the 1936 preface to the German edition of his book, Alexis Carrel had added a praise to the eugenics policies of the Third Reich, writing that:

Carrel also wrote in his book that:

Alexis Carrel had also taken an active part to a symposium in Pontigny organized by Jean Coutrot, the "Entretiens de Pontigny". Scholars such as Lucien Bonnafé, Patrick Tort and Max Lafont have accused Carrel of responsibility for the execution of thousands of mentally ill or impaired patients under Vichy.

A Nazi ordinance

A Nazi ordinance

dated 21 September 1940, forced Jews of the "occupied zone" to declare themselves as such in police office or sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures). Under the responsibility of André Tulard

, head of the Service on Foreign Persons and Jewish Questions at the Prefecture of Police

of Paris, a filing system

registering Jewish people was created. Tulard had previously created such a filing system under the Third Republic, registering members of the Communist Party

(PCF). In the sole department of the Seine, encompassing Paris and its immediate suburbs, nearly 150,000 persons, unaware of the upcoming danger and assisted by the French police, presented themselves to the police offices, in accordance with the military order. The registered information was then centralized by the French police, who constructed, under the direction of inspector Tulard, a central filing system. According to the Dannecker report

, "this filing system is subdivided into files alphabetically classed, Jewish with French nationality and foreign Jewish having files of different colours, and the files were also classed, according to profession, nationality and street" (of residency). These files were then handed over to Theodor Dannecker

, head of the Gestapo in France and under the orders of Adolf Eichmann

, head of the RSHA

IV-D. They were then used by the Gestapo on various raids, among them the August 1941 raid in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, during which 3,200 foreign Jews and 1,000 French Jews were interned in various camps, including Drancy

. Furthermore, the French police noted on this occasion, on each identity document

s of the Jewish people, their registration as Jews. As Italian political philosopher Giorgio Agamben

has pointed out, this racial profiling

was an important step in the organization of the police raids against the French Jewish community.

On 3 October 1940, the Vichy government voluntarily promulgated the first Statute on Jews

, which created a special, underclass

of French Jewish citizens, and enforced, for the first time ever in France, racial segregation

. The October 1940 Statute also excluded Jews from the administration, the armed forces, entertainment, arts, media, and certain professional roles (teachers, lawyers, doctors of medicine, etc.). A Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (CGQJ, Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives), was created on 29 March 1941. It was first directed by Xavier Vallat

, until May 1942, and then by Darquier de Pellepoix until February 1944. Mirroring the Reich Association of Jews, the Union Générale des Israélites de France was founded.

In the German occupied northern zone, yellow badge

s, a reminiscence of old Christian and Muslim Anti-Semitism (Middle Ages) were required to be worn by Jews. Police inspector André Tulard participated in the logistics

concerning the attribution of these badges.

The police also oversaw the confiscation of telephones and radios from Jewish homes and enforced a curfew

on Jews starting from February 1942. It attentively monitored the Jews who did not respect the prohibition, according to which they were not supposed to appear in public places and had to travel in the last car of the Parisian metro.

Along with many French police officers, André Tulard was present on the day of the inauguration of Drancy internment camp

in 1941, which was used largely by French police as the central transit camp for detainees captured in France. All Jews and others "undesirables" passed through Drancy before heading to Auschwitz and other camps

.

with cooperation from authorities of the SNCF

, the state railway company. The police arrested 13,152 Jews, including 4,051 children—which the Gestapo

had not asked for—and 5,082 women on 16 and 17 July, and imprisoned them in the Winter Velodrome in unhygienic conditions. They were led to Drancy internment camp

(run by Nazi Alois Brunner

, who is still wanted for crimes against humanity, and French constabulary police), then crammed into box car transports and shipped by rail to Auschwitz. Most of the victims died enroute due to lack of food or water. The remaining survivors were sent to the gas chambers. This action alone represented more than a quarter of the 42,000 French Jews sent to concentration camps in 1942, of which only 811 would return after the end of the war. Although the Nazi VT (Verfügungstruppe) had initially directed the action, French police authorities vigorously participated. On 16 July 1995, president Jacques Chirac officially apologized for the participation of French police forces in the July 1942 raid. "There was no effective police resistance until the end of Spring of 1944", wrote historians Jean-Luc Einaudi and Maurice Rajsfus

near Aix-en-Provence before joining Drancy. Then, on 22, 23 and 24 January 1943, assisted by Bousquet's police force, the Germans organized a raid in Marseilles. During the Battle of Marseilles, the French police checked the identity document

s of 40,000 people, and the operation succeeded in sending 2,000 Marseillese people in the death trains, leading to the extermination camps. The operation also encompassed the expulsion of an entire neighborhood (30,000 persons) in the Old Port before its destruction. For this occasion, SS-Gruppenführer Karl Oberg, in charge of the German Police in France, made the trip from Paris, and transmitted to Bousquet orders directly received from Himmler

. It is another notable case of the French police's willful collaboration with the Nazis.

in 1974, and after him, other historians such as Robert Paxton

and Jean-Pierre Azéma

have used the term collaborationnistes to refer to fascists and Nazi sympathizers who, for ideological reasons, wished a reinforced collaboration with Hitler's Germany. Examples of these are Parti Populaire Français

(PPF) leader Jacques Doriot

, writer Robert Brasillach

or Marcel Déat

. A principal motivation and ideological foundation among collaborationnistes was anticommunism and the desire to see the defeat of the Bolsheviks.

A number of the French advocated fascist philosophies even before the occupation. Organizations such as La Cagoule

, had contributed to the destabilization of the Third Republic, particularly when the left-wing Popular Front

was in power. A prime example is the founder of L'Oréal

cosmetics, Eugène Schueller

, and his associate Jacques Corrèze

.

Collaborationists may have influenced the Vichy government's policies, but ultra-collaborationists never comprised the majority of the government before 1944.

In order to enforce the régime's will, some paramilitary organizations with a fascist leaning were created. A notable example was the "Légion Française des Combattants" (LFC) (French Legion of Fighters), including at first only former combatants, but quickly adding "Amis de la Légion" and cadets of the Légion, who had never seen battle, but who supported Pétain's régime. The name was then quickly changed to "Légion Française des Combattants et des volontaires de la Révolution Nationale" (French Legion of Fighters and Volunteers of the National Revolution). Joseph Darnand

created a "Service d'Ordre Légionnaire

" (SOL), which consisted mostly of French supporters of the Nazis, of which Pétain fully approved.

The US position towards Vichy France and De Gaulle was especially hesitant and inconsistent. President Roosevelt disliked Charles de Gaulle, whom he regarded as an "apprentice dictator." Robert Murphy

, Roosevelt's representative in North Africa, started preparing the landing in North Africa from December 1940 (i.e. a year before the US entered the war). The US first tried to support General Maxime Weygand

, general delegate of Vichy for Africa until December 1941. This first choice having failed, they turned to Henri Giraud

shortly before the landing in North Africa on 8 November 1942. Finally, after François Darlan

's turn towards the Free Forces - Darlan had been president of Council of Vichy from February 1941 to April 1942 - they played him against de Gaulle. US General Mark W. Clark of the combined Allied command made Admiral Darlan sign on 22 November 1942 a treaty putting "North Africa at the disposition of the Americans" and making France "a vassal country." Washington then imagined, between 1941 and 1942, a protectorate status for France, which would be submitted after the Liberation to an Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories (AMGOT) like Germany. After the assassination of Darlan on 24 December 1942, Washington turned again towards Henri Giraud, to whom had rallied Maurice Couve de Murville

, who had financial responsibilities in Vichy, and Lemaigre-Dubreuil, a former member of La Cagoule

and entrepreneur, as well as Alfred Pose, general director of the Banque nationale pour le commerce et l'industrie (National Bank for Trade and Industry).

To counter the Vichy regime, General Charles de Gaulle created the Free French Forces

To counter the Vichy regime, General Charles de Gaulle created the Free French Forces

(FFL) after his Appeal of 18 June 1940 radio speech. Initially, Winston Churchill

was ambivalent about de Gaulle and he dropped ties with Vichy only when it became clear they would not fight. Even so, the Free France headquarters in London was riven with internal divisions and jealousies.

The additional participation of Free French forces in the Syrian operation was controversial within Allied circles. It raised the prospect of Frenchmen shooting at Frenchmen, raising fears of a civil war. Additionally, it was believed that the Free French were widely reviled within Vichy military circles, and that Vichy forces in Syria were less likely to resist the British if they were not accompanied by elements of the Free French. Nevertheless, de Gaulle convinced Churchill to allow his forces to participate, although de Gaulle was forced to agree to a joint British and Free French proclamation promising that Syria and Lebanon would become fully independent at the end of the war.

However, there were still French naval ships under Vichy French control. A large squadron was in port at Mers El Kébir harbour near Oran

. Vice Admiral Somerville, with Force H

under his command, was instructed to deal with the situation in July 1940. Various terms were offered to the French squadron, but all were rejected. Consequently, Force H opened fire on the French ships

. Nearly 1,000 French sailors died when the blew up in the attack. Less than two weeks after the armistice, Britain had fired upon forces of its former ally. The result was shock and resentment towards the UK within the French Navy, and to a lesser extent in the general French public.

, namely Chad

, French Congo

, and eventually Gabon

went over to the Free French almost immediately, others remained loyal to Vichy France. In time, the majority of the colonies tended to switch to the Allied side peacefully in response to persuasion and to changing events. This did not, however, happen overnight: Guadeloupe

and Martinique

in the West Indies, as well as French Guiana

on the northern coast of South America, did not join the Free French until 1943. Meanwhile, France's Arab colonies (Syria, Algeria

, Tunisia, and Morocco) generally remained under Vichy control until captured by Allied forces. This was chiefly because their proximity to Europe made them easier to maintain without Allied interference; this same proximity also gave them strategic importance for the European theater of the war. Conversely, more remote French possessions sided with the Free French Forces

early, whether upon Free French action such as in Saint Pierre and Miquelon (despite U.S. wishes to the contrary) or spontaneously such as in French Polynesia

.

Relations between the United Kingdom and the Vichy government were difficult. The Vichy government broke off diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 5 July 1940, after the Royal Navy

Relations between the United Kingdom and the Vichy government were difficult. The Vichy government broke off diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 5 July 1940, after the Royal Navy

sank the French ships in port at Mers-el-Kebir

, Algeria. The destruction of the fleet followed a standoff during which the British insisted that the French either scuttle their vessels, sail to a neutral port or join them in the war against Germany. These options were refused and the fleet was destroyed. This move by Britain hardened relations between the two former allies and caused more of the French population to side with Vichy against the British-supported Free French.

On 23 September 1940, the British launched the Battle of Dakar

, also known as Operation Menace. The Battle of Dakar was part of the West Africa Campaign

. Operation Menace was a plan to capture the strategic port of Dakar

in French West Africa

. The port was under the control of the Vichy French. The plan called for installing Free French forces under General Charles de Gaulle in Dakar. By 25 September, the battle was over, the plan was unsuccessful, and Dakar remained under Vichy French control.

Overall, the Battle of Dakar did not go well for the Allies. The Vichy French did not back down. HMS Resolution was so heavily damaged that it had to be towed to Cape Town

. Worse, during most of this conflict, bombers of the Vichy French Air Force

(Armée de l'Air de Vichy) based in North Africa bombed the British base at Gibraltar

. The bombing started on the 24 September in response to the first engagement in Dakar on 23 September. The bombing ended on 25 September. This was after the facilities at Gibraltar

suffered heavy damage.

In June 1941 the next flashpoint between Britain and Vichy France came when a revolt in Iraq

was put down by British forces. German Air Force (Luftwaffe

) and Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica

) aircraft, staging through the French possession of Syria

, intervened in the fighting in small numbers. That highlighted Syria as a threat to British interests in the Middle East. Consequently, on 8 June, British and Commonwealth

forces invaded Syria

and Lebanon

. This was known as the Syria-Lebanon Campaign

or Operation Exporter. The Syrian capital, Damascus

, was captured on 17 June and the five-week campaign ended with the fall of Beirut

and the Convention of Acre (Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre

) on 14 July 1941.

From 5 May to 6 November 1942, another major operation by British and Commonwealth forces against Vichy French territory, took place in Madagascar

. This operation was known as the Battle of Madagascar

, or Operation Ironclad. The British feared that Japanese forces might use Madagascar

as a base and thus cripple British trade and communications in the Indian Ocean. As a result, Madagascar was invaded by British and Commonwealth forces. The landing at Diégo-Suarez

was relatively quick, though it took the British forces six more months to control the whole of the large (587,041 km2), (226,658 mi2 ) island.

This seemingly subservient behavior convinced the regime of Major-General Plaek Pibulsonggram

, the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand, that Vichy France would not seriously resist a confrontation with Thailand. In October 1940, the military forces of Thailand attacked across the border with Indochina

and launched the French-Thai War

. Though the French won an important naval victory

over the Thais, the Japanese forced the French to accept their mediation of a peace treaty that returned parts of Cambodia and Laos that had been taken from Thailand around the turn of the century to Thai control. This territorial loss was a major blow to French pride, especially since the ruins of Angkor Wat

, of which the French were especially proud, were located in the region of Cambodia returned to Thailand.

The French were left in place to administer the colony until 9 March 1945, when the Japanese staged a coup d'état in French Indochina

and took control of Indochina establishing their own colony, Empire of Vietnam

, as a double puppet state

.

in the mid-1930s and during the early stages of World War II, constant border skirmishes occurred between the forces in French Somaliland

and the forces in Italian East Africa

. After the fall of France in 1940, French Somaliland declared loyalty to Vichy France. The colony remained loyal to Vichy France during the East African Campaign

but stayed out of that conflict. This lasted until December 1942. By that time, the Italians had been defeated and the French colony was isolated by a British blockade. Free French and Allied

forces recaptured the colony's capital of Djibouti

at the end of 1942. A local battalion from Djibouti participated in the liberation of France in 1944.

, Algeria, and Tunisia

, started on 8 November 1942, with landings in Morocco and Algeria. The invasion, known as Operation Torch, was launched because the Soviet Union had pressed the United States and Britain to start operations in Europe, and open a second front

to reduce the pressure of German forces on the Russian troops

. While the American commanders favored landing in occupied Europe as soon as possible (Operation Sledgehammer

), the British commanders believed that such a move would end in disaster. An attack on French North Africa was proposed instead. This would clear the Axis Powers

from North Africa, improve naval control of the Mediterranean, and prepare an invasion of Southern Europe in 1943. American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt suspected the operation in North Africa would rule out an invasion of Europe in 1943 but agreed to support British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

By the time the Tunisia Campaign

was fought, the French forces in North Africa had gone over to the Allied side, joining the Free French Forces

.

.

(now Vanuatu

), then a French-British condominium

, Resident Commissioner Henri Sautot quickly led the French community to join the Free French side. The outcome was decided in a public meeting on 20 July 1940 and conveyed to De Gaulle on 22 July 1940.

. A referendum was organized on 2 September 1940 in Tahiti

and Moorea

, with outlying islands reporting agreement in following days. The vote was massively (5564 vs. 18) in favor of joining the Free French

side. Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor

, American forces identified French Polynesia as an ideal refuelling point between Hawaii

and Australia and, with de Gaulle

's agreement, organized "Operation Bobcat" sending nine ships with 5,000 GIs who built a naval refuelling base and airstrip and set up coastal defense guns on Bora Bora

. This first experience was valuable in later Seabee

efforts in the Pacific, and the Bora Bora base supplied the Allied ships and planes that fought the Battle of the Coral Sea

. Troops from French Polynesia and New Caledonia

formed a Bataillon du Pacifique in 1940; became part of the 1st Free French Division

in 1942, distinguishing themselves during the Battle of Bir Hakeim

and subsequently combining with another unit to form the Bataillon d'infanterie de marine et du Pacifique; fought in the Italian Campaign

, distinguishing itself at the Garigliano during the Battle of Monte Cassino

and on to Tuscany

; and participated in the Provence landings and onwards to the liberation of France.

, the local administrator and bishop sided with Vichy, but faced opposition from some of the population and clergy; their attempts at naming a local king in 1941 (to buffer the territory from their opponents) backfired as the newly elected king refused to declare allegiance to Pétain. The situation stagnated for a long while, due to the great remoteness of the islands and the fact that no overseas ship visited the islands for 17 months after January 1941. An aviso

sent from Nouméa

took over Wallis on behalf of the Free French on 27 May 1942, and Futuna on 29 May 1942. This allowed American forces to build an airbase and seaplane base on Wallis (Navy 207) that served the Allied Pacific operations.

, Henri Sautot again led prompt allegiance to the Free French side, effective 19 September 1940. Due to its location on the edge of the Coral Sea and on the flank of Australia, New Caledonia became strategically critical in the effort to combat the Japanese advance in the Pacific in 1941–1942 and to protect the sea lanes between North America and Australia. Nouméa

served as a headquarters of the United States Navy

and Army in the South Pacific, and as a repair base for Allied vessels. New Caledonia contributed personnel both to the Bataillon du Pacifique and to the Free French Naval Forces

that saw action in the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

, to occupy Corsica and then the rest of unoccupied southern zone, in immediate reaction to the landing of the Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch

) on 8 November 1942. Following the conclusion of the operation on 12 November, Vichy's remaining military forces were disbanded. Vichy continued to exercise its remaining jurisdiction over almost all of metropolitan France, with the residual power

devolved into the hands of Laval, until the gradual collapse of the regime following the Allied invasion in June 1944. On 7 September 1944, following the Allied invasion of France, the remainders of the Vichy government cabinet fled to Germany and established a puppet government

in exile at Sigmaringen

. That rump government finally fell when the city was taken by the Allied French army in April 1945.

Part of the residual legitimacy of the Vichy regime resulted from the continued ambivalence of U.S. and British leaders. President Roosevelt continued to cultivate Vichy, and promoted General Henri Giraud

as a preferable alternative to de Gaulle, despite the poor performance of Vichy forces in North Africa—Admiral François Darlan

had landed in Algiers

the day before Operation Torch

. Algiers was headquarters of the Vichy French XIXth Army Corps, which controlled Vichy military units in North Africa. Darlan was neutralized within 15 hours by a 400-strong French resistance force. Roosevelt and Churchill accepted Darlan, rather than de Gaulle, as the French leader in North Africa. De Gaulle had not even been informed of the landing in North Africa. The United States also resented the Free French taking control of St Pierre and Miquelon on 24 December 1941, because, Secretary of State Hull

believed, it interfered with a U.S.-Vichy agreement to maintain the status quo with respect to French territorial possessions in the western hemisphere.

Following the invasion of France via Normandy and Provence (Operation Overlord

and Operation Dragoon

) and the departure of the Vichy leaders, the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union finally recognized the Provisional Government of the French Republic

(GPRF), headed by de Gaulle, as the legitimate government of France on 23 October 1944. Before that, the first return of democracy to mainland France since 1940 had occurred with the declaration of the Free Republic of Vercors

on 3 July 1944, at the behest of the Free French government—but that act of resistance

was quashed by an overwhelming German attack by the end of July.

In North Africa, after the 8 November 1942 putsch by the French resistance, most Vichy figures were arrested (including General Alphonse Juin

In North Africa, after the 8 November 1942 putsch by the French resistance, most Vichy figures were arrested (including General Alphonse Juin

, chief commander in North Africa, and Admiral Darlan). However, Darlan was released and U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

finally accepted his self-nomination as high commissioner of North Africa and French West Africa

(Afrique occidentale française, AOF), a move that enraged de Gaulle, who refused to recognize Darlan's status. After Darlan signed an armistice with the Allies and took power in North Africa, Germany violated the 1940 armistice and invaded Vichy France on 10 November 1942 (operation code-named Case Anton

), triggering the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon

.

Giraud arrived in Algiers on 10 November, and agreed to subordinate himself to Darlan

as the French African army commander. Even though he was now in the Allied camp, Darlan maintained the repressive Vichy system in North Africa, including concentration camp

s in southern Algeria

and racist laws. Detainees were also forced to work on the Transsaharien railroad. Jewish goods were "aryanized" (i.e., stolen), and a special Jewish Affair service was created, directed by Pierre Gazagne. Numerous Jewish children were prohibited from going to school, something which not even Vichy had implemented in metropolitan France. The admiral was killed on 24 December 1942, in Algiers by the young monarchist Bonnier de La Chapelle. Although de la Chapelle had been a member of the resistance group led by Henri d'Astier de La Vigerie

, it is believed he was acting as an individual.

After Admiral Darlan's assassination, Giraud became his de facto successor in French Africa with Allied support. This occurred through a series of consultations between Giraud and de Gaulle. The latter wanted to pursue a political position in France and agreed to have Giraud as commander in chief, as the more qualified military person of the two. It is questionable that he ordered that many French resistance leaders who had helped Eisenhower's troops be arrested, without any protest by Roosevelt's representative, Robert Murphy

. Later, the Americans sent Jean Monnet

to counsel Giraud and to press him into repeal the Vichy laws. After difficult negotiations, Giraud agreed to suppress the racist laws, and to liberate Vichy prisoners of the South Algerian concentration camps. The Cremieux decree, which granted French citizenship to Jews in Algeria and which had been repealed by Vichy, was immediately restored by General de Gaulle.

Giraud took part in the Casablanca conference

, with Roosevelt, Churchill and de Gaulle, in January 1943. The Allies discussed their general strategy for the war, and recognized joint leadership of North Africa by Giraud and de Gaulle. Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle then became co-presidents of the Comité français de la Libération Nationale

, which unified the Free French Forces

and territories controlled by them and had been founded at the end of 1943. Democratic rule was restored in French Algeria

, and the Communists and Jews liberated from the concentration camps.

At the end of April 1945 Pierre Gazagne, secretary of the general government headed by Yves Chataigneau, took advantage of his absence to exile anti-imperialist leader Messali Hadj

and arrest the leaders of his party, the Algerian People's Party

(PPA). On the day of the Liberation of France, the GPRF would harshly repress a rebellion in Algeria during the Sétif massacre

of 8 May 1945, which has been qualified by some historians as the "real beginning of the Algerian War".

(SOL) collaborationist militia, headed by Joseph Darnand

, became independent and was transformed into the "Milice française" (French Militia). Officially directed by Pierre Laval

himself, the SOL was led by Darnand, who held an SS rank and pledged an oath of loyalty to Hitler

. Under Darnand and his sub-commanders, such as Paul Touvier

and Jacques de Bernonville

, the Milice was responsible for helping the German forces and police in the repression of the French Resistance

and Maquis

.

In addition, the Milice

In addition, the Milice

participated with area Gestapo

head Klaus Barbie

in seizing members of the resistance and minorities including Jews for shipment to detention centres, such as the Drancy deportation camp, en route to Auschwitz

, and other German concentration camps, including Dachau and Buchenwald.

, less than half of them with French citizenship (and the others foreigners, mostly exiles from Germany during the 1930s). About 200,000 of them, and the large majority of foreign Jews, lived in Paris and its outskirts. Among the 150,000 French Jews, about 30,000, generally native from Central Europe, had been naturalized

French during the 1930s. Of the total, approximatively 25,000 French Jews and 50,000 foreign Jews were deported. According to historian Robert Paxton

, 76,000 Jews were deported and died in concentration and extermination camps. Including the Jews who died in concentration camps in France

, this would have made for a total figure of 90,000 Jewish deaths (a quarter of the total Jewish population before the war, by his estimate). Paxton's numbers imply that 14,000 Jews died in French concentration camps. However, the systematic census of Jewish deportees from France (citizens or not) drawn under Serge Klarsfeld concluded that 3,000 had died in French concentration camps and 1,000 more had been shot. Of the approximately 76,000 deported, 2,566 survived. The total thus reported is slightly below 77,500 dead (somewhat less than a quarter of the Jewish population in France in 1940).

Proportionally, either number makes for a lower death toll than in some other countries (in the Netherlands, 75% of the Jewish population was murdered). This fact has been used as arguments by supporters of Vichy. However, according to Paxton, the figure would have been greatly lower if the "French state" had not willfully collaborated with Germany, which lacked staff for police activities. During the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, Laval ordered the deportation of the children, against explicit German orders. Paxton pointed out that if the total number of victims had not been higher, it was due to the shortage in wagons, the resistance of the civilian population and deportation in other countries (notably in Italy).

Following the Liberation of Paris

Following the Liberation of Paris

on 25 August 1944, Pétain and his ministers were taken to Germany by the German forces. There, Fernand de Brinon

established a government in exile

at Sigmaringen

—in which Pétain refused to participate—until 22 April 1945. The government was situated in Sigmaringen Castle, and its official title was the French Delegation or the French Government Commission for the Protection of National Interests . Sigmaringen had its own radio (Radio-patrie, Içi la France), press (La France, Le Petit Parisien

) and hosted the embassies of the Axis powers, Germany, Italy and Japan. The population of the Vichy French enclave was about 6,000 citizens including known collaborationist journalists, writers (Louis-Ferdinand Céline

, Lucien Rebatet

), actors (Le Vigan) and their families plus 500 soldiers, 700 French SS, POWs and French civilian forced labourers

. On 8 January 1945, Jacques Doriot set up the "Committee of French liberation" at Neustadt an der Weinstraße

, shortly before being killed in an Allied air attack.

. The first action of that government was to re-establish republican legality throughout metropolitan France.

The provisional government considered that the Vichy government had been unconstitutional and thus that all its actions had been illegal. All statutes, laws, regulations and decisions by the Vichy government were thus made null and devoid of effects. However, since mass cancellation of all decisions taken by Vichy, including many that could have been taken as well by Republican governments, was impractical, it was decided that cancellation was to be expressly acknowledged by the government. A number of laws and acts were however explicitly repealed, including all constitutional acts, all laws discriminating against Jews, all acts against "secret societies" (e.g. Freemasons), and all acts creating special tribunals.

Collaborationist paramilitary

and political organizations, such as the Milice

and the Service d'ordre légionnaire

, were also disbanded.

The provisional government also took steps to replace local governments, including governments that had been suppressed by the Vichy regime, through new elections or by extending the terms of those who had been elected no later than 1939.

, Fresnes prison or the Drancy internment camp

. Women who were suspected of having romantic liaisons with Germans, or more often of being prostitutes who had entertained German customers, were publicly humiliated by having their heads shaved. Those who had engaged in the black market were also stigmatized as "war profiteers" (profiteurs de guerre), and popularly called "BOF" (Beurre Oeuf Fromage, or Butter Eggs Cheese, because of the products sold at outrageous prices during the Occupation). However, the Provisional Government of the French Republic

(GPRF, 1944–46) quickly reestablished order, and brought Collaborationists before the courts. Many convicted Collaborationists were then amnestied

under the Fourth Republic

(1946–54).

Four different periods are distinguished by historians:

Other historians have distinguished the purges against intellectuals (Brasillach, Céline, etc.), industrialists, fighters (LVF, etc.) and civil servants (Papon, etc.).

Philippe Pétain was charged with treason in July 1945. He was convicted and sentenced to death by firing squad, but Charles de Gaulle commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. In the police, some collaborators soon resumed official responsibilities. This continuity of the administration was pointed out, in particular concerning the events of the Paris massacre of 1961

, executed under the orders of head of the Parisian police Maurice Papon

when Charles de Gaulle was head of state. Papon was tried and convicted for crimes against humanity in 1998.

The French members of the Waffen-SS Charlemagne Division who survived the war were regarded as traitors. Some of the more prominent officers were executed, while the rank-and-file were given prison terms; some of them were given the option of doing time in Indochina (1946–54) with the Foreign Legion instead of prison.

Among artists, singer Tino Rossi

was detained in Fresnes prison

, where, according to Combat

newspaper, prison guards asked him for autographs. Pierre Benoit

and Arletty

were also detained.

Executions without trials and other forms of "popular justice" were harshly criticized immediately after the war, with circles close to Pétainists advancing the figures of 100,000, and denouncing the "Red Terror

", "anarchy

", or "blind vengeance". The writer and Jewish internee Robert Aron

estimated the popular executions to a number of 40,000 in 1960. This surprised de Gaulle, who estimated the number to be around 10,000, which is also the figure accepted today by mainstream historians. Approximately 9,000 of these 10,000 refer to summary executions in the whole of the country, which occurred during battle.

Some imply that France did too little to deal with collaborators at this stage, by selectively pointing out that in absolute value (numbers), there were fewer legal executions in France than in its smaller neighbor Belgium, and fewer internments than in Norway or the Netherlands. However, the situation in Belgium was not comparable as it mixed collaboration with elements of a war of secession: The 1940 invasion prompted the Flemish population to generally side with the Germans in the hope of gaining national recognition, and relative to national population a much higher proportion of Belgians than French thus ended up collaborating with the Nazis or volunteering to fight alongside them; the Walloon population in turn led massive anti-Flemish retribution after the war, some of which, such as the execution of Irma Swertvaeger Laplasse, remained controversial.

The proportion of collaborators was also higher in Norway, and collaboration occurred on a larger scale in the Netherlands (as in Flanders) based partly on linguistic and cultural commonality with Germany. The internments in Norway and Netherlands, meanwhile, were highly temporary and were rather indiscriminate; there was a brief internment peak in these countries as internment was used partly for the purpose of separating Collaborationists from non-Collaborationists. Norway ended up executing only 37 Collaborationists.

, Klaus Barbie

, Maurice Papon

, René Bousquet, head of French police during the war, and his deputy Jean Leguay

(the last two were both convicted for their responsibilities in the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942). Among others, Nazi hunter

s Serge and Beate Klarsfeld

spent part of their post-war effort trying to bring them before the courts. A fair number of collaborationists then joined the OAS terrorist movement during the Algerian War (1954–62). Jacques de Bernonville

escaped to Quebec, then Brazil. Jacques Ploncard d'Assac became counsellor to the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar

in Portugal.

In 1993 former Vichy official René Bousquet was assassinated while he awaited prosecution in Paris following a 1991 inculpation for crimes against humanity; he had been prosecuted but partially acquitted and immediately amnestied in 1949. In 1994 former Vichy official Paul Touvier

(1915–1996) was convicted of crimes against humanity. Maurice Papon

was likewise convicted in 1998, released three years later due to ill health, and died in 2007.

's presidency, the official point of view of the French government was that the Vichy regime was an illegal government distinct from the French Republic, established by traitors under foreign influence. Indeed, Vichy France eschewed the formal name of France ("French Republic") and styled itself the "French State", replacing the Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité

Republican motto, inherited from the 1789 French Revolution

, with the reactionary

Travail, Famille, Patrie

motto.

While the criminal behavior of Vichy France is acknowledged, this point of view denies any responsibility of the state of France, alleging that acts committed between 1940 and 1944 were unconstitutional acts devoid of legitimacy. The main proponent of this view was Charles de Gaulle himself, who insisted, as did other historians afterwards, on the unclear conditions of the June 1940 vote granting full powers to Pétain, which was refused by the minority of Vichy 80. In particular, coercive measures used by Pierre Laval have been denounced by those historians who hold that the vote did not, therefore, have Constitutional legality (See subsection: Conditions of armistice and 10 July 1940 vote of full powers).

Nevertheless, on 16 July 1995, president Jacques Chirac

, in a speech, recognized the responsibility of the French State for seconding the "criminal folly of the occupying country", in particular the help of the French police, headed by René Bousquet, which assisted the Nazis in the enactment of the so-called "Final Solution". The July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup is a tragic example of how the French police did the Nazi work, going even further than what military orders demanded (by sending children to Drancy internment camp, last stop before the extermination camps).

As historian Henry Rousso has put it in The Vichy Syndrome (1987), Vichy and the state collaboration of France remains a "past that doesn't pass." Historiographical debates are still, today, passionate, opposing conflictual views on the nature and legitimacy of Vichy's collaborationism with Germany in the implementation of the Holocaust. Three main periods have been distinguished in the historiography of Vichy: first the Gaullist period, which aimed at national reconciliation and unity under the figure of Charles de Gaulle, who conceived himself above political parties and divisions; then the 1960s, with Marcel Ophüls

's film The Sorrow and the Pity

(1971); finally the 1990s, with the trial of Maurice Papon

, civil servant in Bordeaux in charge of the "Jewish Questions" during the war, who was convicted after a very long trial (1981–1998) for crimes against humanity. The trial of Papon did not only concern an individual itinerary, but the French administration's collective responsibility in the deportation of the Jews. Furthermore, his career after the war, which led him to be successively prefect of the Paris police during the Algerian War (1954–1962) and then treasurer of the Gaullist UDR

party from 1968 to 1971, and finally Budget Minister under president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

and prime minister Raymond Barre

from 1978 to 1981, was symptomatic of the quick rehabilitation of former Collaborationists after the war. Critics contend that this itinerary, shared by others (although few had such public roles), demonstrates France's collective amnesia, while others point out that the perception of the war and of the state collaboration has evolved during these years. Papon's career was considered more scandalous as he had been responsible, during his function as prefect of police of Paris, for the 1961 Paris massacre of Algerians during the war, and was forced to resign from this position after the "disappearance", in Paris in 1965, of the Moroccan anti-colonialist leader Mehdi Ben Barka

.

While it is certain that the Vichy government and a large number of its high administration collaborated in the implementation of the Holocaust, the exact level of such cooperation is still debated. Compared with the Jewish communities established in other countries invaded by Germany, French Jews suffered proportionately lighter losses (see Jewish death toll section above); although, starting in 1942, repression and deportations struck French Jews as well as foreign Jews. Former Vichy officials later claimed that they did as much as they could to minimize the impact of the Nazi policies, although mainstream French historians contend that the Vichy regime went beyond the Nazi expectations.

The regional newspaper Nice Matin revealed on 28 February 2007, that in more than 1,000 condominium

properties on the Côte d'Azur, rules dating to Vichy were still "in force", or at least existed on paper. One of these rules, for example, stated that:

The president of the CRIF

-Côte d'Azur, a Jewish association group, issued a strong condemnation labeling it "the utmost horror" when one of the inhabitants of such a condominium qualified this as an "anachronism" with "no consequences." Jewish inhabitants were able and willing to live in the buildings, and to explain this the Nice Matin reporter surmised that some tenants may have not read the condominium contracts in detail, while others deemed the rules obsolete. A reason for the latter is that any racially discriminatory condominium or other local rule that may have existed "on paper", Vichy-era or otherwise, was invalidated by the constitutions of the French Fourth Republic

(1946) and French Fifth Republic