Paris Commune

Encyclopedia

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

from March 18 (more formally, from March 28) to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

and Marxists

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

during the Industrial Revolution. Debates over the policies and outcome of the Commune contributed to the break between those two political groups.

In a formal sense, the Paris Commune simply acted as the local authority, the city council (in French, the "commune"), which exercised power in Paris for two months in the spring of 1871. However, the conditions in which it formed, its controversial decrees, and its violent end make its tenure one of the more important political episodes of the time.

Background

The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

. This uprising was chiefly caused by the disaster in the war and the growing discontent among French workers. The worker discontent can be traced to the first worker uprisings, the Canut Revolts

Canut revolts

Three major revolts by silk workers in Lyon, France, called the Canut revolts took place during the first half of the 19th century. The first occurred in November 1831, and was the first clearly defined worker uprising of the Industrial Revolution....

, in Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

and Paris in the 1830s (a Canut

Canut

The canuts were Lyonnais silk workers, often working on Jacquard looms. They were primarily found in the Croix-Rousse neighbourhood of Lyon in the 19th century. Although the term generally refers to Lyonnais silk workers, silk workers in the commune of l'Arbresle are also called canuts.-Canut...

was a Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

nais silk worker, often working on Jacquard loom

Jacquard loom

The Jacquard loom is a mechanical loom, invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801, that simplifies the process of manufacturing textiles with complex patterns such as brocade, damask and matelasse. The loom is controlled by punched cards with punched holes, each row of which corresponds to one row...

s).

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

, way of managing the economy, summed up in the popular appeal for "la république démocratique et sociale!" ("the democratic and social republic!")

The war with Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, initiated by Napoleon III in July 1870, turned out disastrously for France, and by September Paris itself was under siege

Siege of Paris

The Siege of Paris, lasting from September 19, 1870 – January 28, 1871, and the consequent capture of the city by Prussian forces led to French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of the German Empire as well as the Paris Commune....

. The gap between rich and poor in the capital had widened during the preceding years, and then food shortages, military failures, and, finally, a Prussian bombardment of the city contributed to a widespread discontent.

In January 1871, after four months of siege the moderate republican Government of National Defense

Government of National Defense

Le Gouvernement de la Défense Nationale, or The Government of National Defence, was the first Government of the Third Republic of France from September 4, 1870, to February 13, 1871, during the Franco-Prussian War, formed after the Emperor Louis Napoleon III was captured by the Prussian army. The...

sought an armistice with the newly proclaimed German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. The Germans included a triumphal entry into Paris in their peace terms. Given the hardships of the siege, many Parisians were bitterly resentful of the Prussians (now at the head of the German Empire) being allowed even a brief ceremonial occupation of their city.

Hundreds of thousands of Parisians were armed members of a citizens' militia known as the "National Guard

National Guard (France)

The National Guard was the name given at the time of the French Revolution to the militias formed in each city, in imitation of the National Guard created in Paris. It was a military force separate from the regular army...

," which had been greatly expanded to help defend the city. Guard units elected their own officers, who, in working-class districts, included radical and socialist leaders.

Steps were taken to form a "Central Committee" of the Guard, including patriotic republicans and socialists, both to defend Paris against a possible German attack and also to defend the republic against a possible royalist restoration. The election of a monarchist majority to the new National Assembly in February 1871 made such fears seem plausible.

The population of Paris was defiant in the face of defeat and prepared to fight if the entry of the German army into the city should provoke them sufficiently. Before German troops entered Paris, National Guardsmen, helped by ordinary working people, managed to move large numbers of cannon (which they regarded as their own property because they had been partly paid for by public subscription) away from the Germans' path and store them in "safe" districts. One of the chief "cannon parks" was on the heights of Montmartre

Montmartre

Montmartre is a hill which is 130 metres high, giving its name to the surrounding district, in the north of Paris in the 18th arrondissement, a part of the Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for the white-domed Basilica of the Sacré Cœur on its summit and as a nightclub district...

.

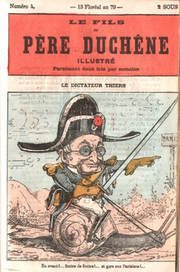

Adolphe Thiers

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers was a French politician and historian. was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871...

was elected "Executive Power" of the new government to postpone the issue of whether to have a president or king. Thiers, as head of the new provisional national government, realized that in the current unstable situation the Central Committee of the Guard formed an alternative centre of political and military power. He was also concerned that workers would arm themselves with the National Guard's weapons and provoke the Germans.

Rise and nature

The Germans entered Paris briefly and left again without incident, but Paris continued to be in a state of high political excitement. The newly elected National Assembly was in the process of moving to BordeauxBordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

from Versailles

Versailles

Versailles , a city renowned for its château, the Palace of Versailles, was the de facto capital of the kingdom of France for over a century, from 1682 to 1789. It is now a wealthy suburb of Paris and remains an important administrative and judicial centre...

(several miles south-west of Paris), having decided that the capital city was too turbulent for them to meet there. Their absence created a power vacuum in Paris as well as suspicion about the National Assembly's intentions, as it had a large royalist majority.

As the Central Committee of the National Guard adopted an increasingly radical stance and steadily gained authority, the government felt that it could not indefinitely allow it to have four hundred cannon at its disposal. So, as a first step, on March 18, 1871, Thiers ordered regular troops to seize the cannon stored on the Butte Montmartre and in other locations across the city. The soldiers, however, whose morale was low, fraternized

Fraternization

Fraternization is "turning people into brothers"—conducting social relations with people who are actually unrelated and/or of a different class as though they were siblings, family members, personal friends or lovers....

with National Guards and local residents. The general at Montmartre, Claude Martin Lecomte, who was later said to have ordered them to fire on the crowd of National Guards and civilians, was dragged from his horse and later shot, together with General Thomas—a veteran republican now hated as former commander of the National Guard—who was seized nearby.

The 92 members of the "Communal Council" included a high proportion of skilled workers and several professionals (such as doctors and journalists). Many of them were political activists, ranging from reformist republicans, various types of socialists, to the Jacobins

Jacobin (politics)

A Jacobin , in the context of the French Revolution, was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary far-left political movement. The Jacobin Club was the most famous political club of the French Revolution. So called from the Dominican convent where they originally met, in the Rue St. Jacques ,...

who tended to look back nostalgically to the Revolution of 1789

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

.

Louis Auguste Blanqui

Louis Auguste Blanqui was a French political activist, notable for the revolutionary theory of Blanquism, attributed to him....

, was hoped by his followers to be a potential leader of the revolution, but he had been arrested on March 17 and was held in prison throughout the life of the Commune. The Commune unsuccessfully tried to exchange him, first against Georges Darboy

Georges Darboy

Georges Darboy was a French Catholic priest, later bishop of Nancy then archbishop of Paris. He was among a group of prominent hostages executed as the Paris Commune of 1871 was about to be overthrown....

, Archbishop of Paris

Archbishop of Paris

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Paris is one of twenty-three archdioceses of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The original diocese is traditionally thought to have been created in the 3rd century by St. Denis and corresponded with the Civitas Parisiorum; it was elevated to an archdiocese on...

, then against all 74 hostages it detained, but flatly refused (see below). The Paris Commune was proclaimed on March 28, although local districts often retained the organizations from the siege.

Social measures

The commune adopted the previously discarded French Republican CalendarFrench Republican Calendar

The French Republican Calendar or French Revolutionary Calendar was a calendar created and implemented during the French Revolution, and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days by the Paris Commune in 1871...

during its brief existence and used the socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

red flag

Red flag

In politics, a red flag is a symbol of Socialism, or Communism, or sometimes left-wing politics in general. It has been associated with left-wing politics since the French Revolution. Socialists adopted the symbol during the Revolutions of 1848 and it became a symbol of communism as a result of its...

rather than the republican tricolour

Flag of France

The national flag of France is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured royal blue , white, and red...

. In 1848, during the Second Republic

French Second Republic

The French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

, radicals and socialists had also adopted the red flag to distinguish themselves from moderate Republicans; this was similar to the symbolic distinctions adopted by the moderate, liberal, Girondist

Girondist

The Girondists were a political faction in France within the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention during the French Revolution...

movement during the 1789 revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

.

Despite internal differences, the Council made a good start in organizing the public services essential for a city of two million. It also reached consensus on certain policies that tended towards a progressive, secular, and highly-democratic social democracy

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

, rather than a true social revolution. Because the Commune was able to meet on fewer than sixty days in all, only a few decrees were actually implemented. These included:

- the separation of church and stateSeparation of church and stateThe concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

; - the remission of rents owed for the entire period of the siege (during which, payment had been suspended);

- the abolition of night work in the hundreds of Paris bakeriesBakeryA bakery is an establishment which produces and sells flour-based food baked in an oven such as bread, cakes, pastries and pies. Some retail bakeries are also cafés, serving coffee and tea to customers who wish to consume the baked goods on the premises.-See also:*Baker*Cake...

; - the granting of pensionPensionIn general, a pension is an arrangement to provide people with an income when they are no longer earning a regular income from employment. Pensions should not be confused with severance pay; the former is paid in regular installments, while the latter is paid in one lump sum.The terms retirement...

s to the unmarried companions and children of National Guards killed on active service; - the free return, by the city pawnshops, of all workmen's tools and household items valued up to 20 francs, pledged during the siege; the Commune was concerned that skilled workers had been forced to pawn their tools during the war;

- the postponement of commercial debtDebtA debt is an obligation owed by one party to a second party, the creditor; usually this refers to assets granted by the creditor to the debtor, but the term can also be used metaphorically to cover moral obligations and other interactions not based on economic value.A debt is created when a...

obligations, and the abolition of interest on the debts; and - the right of employees to take over and run an enterpriseWorkers' self-managementWorker self-management is a form of workplace decision-making in which the workers themselves agree on choices instead of an owner or traditional supervisor telling workers what to do, how to do it and where to do it...

if it were deserted by its owner; the Commune, nonetheless, recognized the previous owner's right to compensation.

The decrees separated the church from the state, made all church property public property, and excluded the practice of religion from schools. (After the fall of the Commune, separation of Church and State, or laïcité

Laïcité

French secularism, in French, laïcité is a concept denoting the absence of religious involvement in government affairs as well as absence of government involvement in religious affairs. French secularism has a long history but the current regime is based on the 1905 French law on the Separation of...

, would not enter French law again until 1880-81 during the Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

, with the signing of the Jules Ferry laws

Jules Ferry laws

The Jules Ferry Laws are a set of French Laws which established free education , then mandatory and laic education . Jules Ferry, a lawyer holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, is widely credited for creating the modern Republican School...

and the 1905 French law on the separation of Church and State

1905 French law on the separation of Church and State

The 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and State was passed by the Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1905. Enacted during the Third Republic, it established state secularism in France...

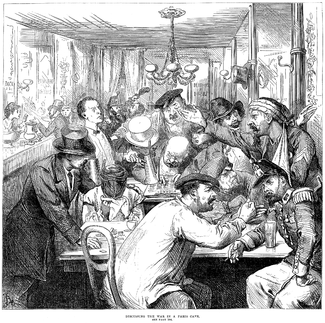

.) The churches were allowed to continue their religious activity only if they kept their doors open for public political meetings during the evenings. Along with the streets and the café

Café

A café , also spelled cafe, in most countries refers to an establishment which focuses on serving coffee, like an American coffeehouse. In the United States, it may refer to an informal restaurant, offering a range of hot meals and made-to-order sandwiches...

s, the churches became centres for political discussions and activities.

Other projected legislation dealt with educational reforms that would make further education and technical training freely available to all.

Feminist initiatives

Some women organized a feminist movementFeminism in France

Feminism in France has its origins in the French Revolution. A few famous figures emerged during the 1871 Paris Commune, including Louise Michel, Russian-born Elisabeth Dmitrieff, Nathalie Lemel, and Renée Vivien .-French Revolution:...

, following on from earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Thus, Nathalie Lemel

Nathalie Lemel

Nathalie Lemel , was a militant anarchist and feminist who participated on the barricades at the Commune de Paris of 1871. She was deported to Nouvelle Calédonie with Louise Michel.-The Bookbinder:...

, a socialist bookbinder, and Élisabeth Dmitrieff

Élisabeth Dmitrieff

Elisabeth Dmitrieff was a Russian-born feminist and actress of the 1871 Paris Commune. Born Elisaviéta Loukinitcha Koucheleva, she was a co-founder of the Women's Union, created on 11 April 1871, in a café of the rue du Temple, with Nathalie Lemel.-Life:Elisabeth Dmitrieff was the daughter of a...

, a young Russian exile and member of the Russian section of the First International (IWA), created the Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés ("Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Injured") on April 11, 1871. The feminist writer André Léo, a friend of Paule Minck, was also active in the Women's Union. Believing that their struggle against patriarchy

Patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which the role of the male as the primary authority figure is central to social organization, and where fathers hold authority over women, children, and property. It implies the institutions of male rule and privilege, and entails female subordination...

could only be pursued through a global struggle against capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, the association demanded gender equality

Gender equality

Gender equality is the goal of the equality of the genders, stemming from a belief in the injustice of myriad forms of gender inequality.- Concept :...

, wages' equality

Equal pay for women

Equal pay for women is an issue regarding pay inequality between men and women. It is often introduced into domestic politics in many first world countries as an economic problem that needs governmental intervention via regulation...

, the right of divorce for women, the right to secular education

Secular education

Secular education is the system of public education in countries with a secular government or separation between religion and state.An example of a highly secular educational system would be the French public educational system, going as far as to ban conspicuous religious symbols in schools.In...

and professional education for girls. They also demanded suppression of the distinction between married women and concubines, and between legitimate and illegitimate children. They advocated the abolition of prostitution

Prostitution

Prostitution is the act or practice of providing sexual services to another person in return for payment. The person who receives payment for sexual services is called a prostitute and the person who receives such services is known by a multitude of terms, including a "john". Prostitution is one of...

(obtaining the closing of the maisons de tolérance, or legal official brothel

Brothel

Brothels are business establishments where patrons can engage in sexual activities with prostitutes. Brothels are known under a variety of names, including bordello, cathouse, knocking shop, whorehouse, strumpet house, sporting house, house of ill repute, house of prostitution, and bawdy house...

s). The Women's Union also participated in several municipal commissions and organized cooperative workshops. Along with Eugène Varlin

Eugène Varlin

Eugène Varlin was a French socialist, communard and member of the First International. He was one of the pioneers of French syndicalism.-Early Activism:...

, Nathalie Le Mel created the cooperative

Cooperative

A cooperative is a business organization owned and operated by a group of individuals for their mutual benefit...

restaurant La Marmite, which served free food for indigents, and then fought during the Bloody Week on the barricades.

Paule Minck opened a free school in the Church of Saint Pierre de Montmartre

Saint Pierre de Montmartre

The Church of Saint Peter of Montmartre is the lesser known of the two main churches on Montmartre in Paris, the other being the 19th-century Sacré-Cœur Basilica...

and animated the Club Saint-Sulpice on the Left Bank. The Russian Anne Jaclard

Anne Jaclard

Note: This article deals with the Russian-born nineteenth-century revolutionary, not with the American Marxist-Humanist theoretician Anne Jaclard....

, who declined to marry Dostoievsky and finally became the wife of Blanquist activist Victor Jaclard

Victor Jaclard

Charles Victor Jaclard was a French revolutionary socialist, a member of the First International and of the Paris Commune.-Early Life:...

, founded the newspaper Paris Commune with André Léo. She was also a member of the Comité de vigilance de Montmartre

Comité de vigilance de Montmartre

The Vigilance Committee of Montmartre was a political association and provisional administrative organization established on the Rue de Clignancourt shortly before the siege of Paris...

, along with Louise Michel

Louise Michel

Louise Michel was a French anarchist, school teacher and medical worker. She often used the pseudonym Clémence and was also known as the red virgin of Montmartre...

and Paule Minck, as well as of the Russian section of the First International. Victorine Brocher, close to the IWA activists, and founder of a cooperative bakery in 1867, also fought during the Commune and the Bloody Week.

Famous figures such as Louise Michel, the "Red Virgin of Montmartre," who joined the National Guard and would later be sent to New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

, symbolized the active participation of a small number of women in the insurrectionary events. A female battalion from the National Guard defended the Place Blanche

Place Blanche

Place Blanche in Paris, France is one of the small plazas along the Boulevard de Clichy, which runs between the 9th and 18th arrondissements and leads into Montmartre....

during the repression.

Local organizations

The workload of the Commune leaders was enormous. The Council members (who were not "representatives" but delegates, subject in theory to immediate recall by their electors) were expected to carry out many executive and military functions as well as their legislative ones. The numerous ad hoc organisations set up during the siege in the localities ("quartiers") to meet social needs (canteens and first aidFirst aid

First aid is the provision of initial care for an illness or injury. It is usually performed by non-expert, but trained personnel to a sick or injured person until definitive medical treatment can be accessed. Certain self-limiting illnesses or minor injuries may not require further medical care...

stations, for example) continued to thrive and cooperate with the Commune.

At the same time, these local assemblies pursued their own goals, usually under the direction of local workers. Despite the formal reformism of the Commune council, the composition of the Commune as a whole was much more revolutionary. Revolutionary factions included Proudhonists (an early form of moderate anarchism

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

), members of the international socialists

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

, Blanquists, and more libertarian republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

ans. The Paris Commune has been celebrated by anarchist

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

s and Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

s ever since then, due to the variety of political undercurrents, the high degree of workers' control, and the remarkable co-operation among different revolutionists.

For example, in the third arrondissement, school materials were provided free, three parochial schools were "laicised", and an orphanage was established. In the twentieth arrondissement, schoolchildren were provided with free clothing and food. There were many similar examples, but a vital ingredient in the Commune's relative success, at this stage, was the initiative shown by ordinary workers who managed to take on the responsibilities of the administrators and specialists who had been removed by .

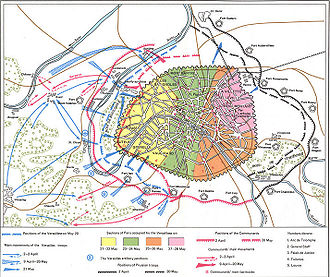

After only a week, the Commune came under attack by elements of the army (which eventually included former prisoners of war released by the Germans) being reinforced at a furious pace at Versailles.

Assault

The Commune forces, the National Guard, first began skirmishing with the regular Army of Versailles on April 2. Neither side really sought a major civil war, nor was either side ever willing to negotiate.

Courbevoie

Courbevoie is a commune located very close to the centre of Paris, France. The centre of Courbevoie is situated 2 kilometres from the outer limits of Paris and 8.2 km...

was occupied by the government forces on April 2, and a delayed attempt by the Commune's forces to march on Versailles on April 3 failed ignominiously. Defence and survival became overriding considerations, and the Commune leadership made a determined effort to turn the National Guard into an effective defense force.

Strong support also came from the large foreign community of political refugees and exiles in Paris: one of them, the Polish ex-officer and nationalist Jarosław Dąbrowski, was to be the Commune's best general. The Council was fully committed to internationalism

Internationalism (politics)

Internationalism is a political movement which advocates a greater economic and political cooperation among nations for the theoretical benefit of all...

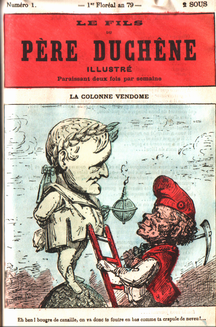

, and in the name of brotherhood the Vendôme Column, celebrating the victories of Napoleon I

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

, and considered by the Commune to be a monument to Bonapartism and chauvinism

Chauvinism

Chauvinism, in its original and primary meaning, is an exaggerated, bellicose patriotism and a belief in national superiority and glory. It is an eponym of a possibly fictional French soldier Nicolas Chauvin who was credited with many superhuman feats in the Napoleonic wars.By extension it has come...

, was pulled down.

Abroad, there were rallies and messages of goodwill sent by trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

and socialist organisations, including some in Germany. But any hopes of getting serious help from other French cities were soon dashed. Thiers and his ministers in Versailles managed to prevent almost all information from leaking out of Paris; and in provincial and rural France there had always been a skeptical attitude towards the activities of the metropolis. Movements in Narbonne

Narbonne

Narbonne is a commune in southern France in the Languedoc-Roussillon region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. Once a prosperous port, it is now located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea...

, Limoges

Limoges

Limoges |Limousin]] dialect of Occitan) is a city and commune, the capital of the Haute-Vienne department and the administrative capital of the Limousin région in west-central France....

, and Marseille

Marseille

Marseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

were quickly crushed.

As the situation deteriorated further, a section of the Council won a vote (opposed by bookbinder Eugène Varlin

Eugène Varlin

Eugène Varlin was a French socialist, communard and member of the First International. He was one of the pioneers of French syndicalism.-Early Activism:...

, an associate of Michael Bakunin and correspondent of Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

, and by other radicals) for the creation of a "Committee of Public Safety," modelled on the Jacobin organ with the same title

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety , created in April 1793 by the National Convention and then restructured in July 1793, formed the de facto executive government in France during the Reign of Terror , a stage of the French Revolution...

that was formed in 1792. Its powers were extensive and ruthless in theory, but in practice it was ineffective.

The strong local loyalties that had been a positive feature of the Commune now became something of a disadvantage: instead of an overall planned defence, each "quartier" fought desperately for its survival, and each was overcome in turn. The webs of narrow streets that made entire districts nearly impregnable in earlier Parisian revolutions had been largely replaced by wide boulevard

Boulevard

A Boulevard is type of road, usually a wide, multi-lane arterial thoroughfare, divided with a median down the centre, and roadways along each side designed as slow travel and parking lanes and for bicycle and pedestrian usage, often with an above-average quality of landscaping and scenery...

s during Haussmann's renovation of Paris

Haussmann's renovation of Paris

Haussmann's Renovation of Paris, or the Haussmann Plan, was a modernization program of Paris commissioned by Napoléon III and led by the Seine prefect, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, between 1853 and 1870...

. The Versaillese enjoyed a centralized command and had superior numbers. They had learned the tactics of street fighting and simply tunnelled through the walls of houses to outflank the Communards' barricades. Ironically, only where Haussmann had made wide spaces and streets were they held up by the defenders' gunfire.

During the assault, the government troops were responsible for slaughtering National Guard troops and civilians: many prisoners taken in possession of weapons, or who were suspected of having fought, were shot out of hand; summary execution

Summary execution

A summary execution is a variety of execution in which a person is killed on the spot without trial or after a show trial. Summary executions have been practiced by the police, military, and paramilitary organizations and are associated with guerrilla warfare, counter-insurgency, terrorism, and...

s were commonplace.

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

or partisan of the regular government of the Paris Commune would be followed on the spot by the execution of the triple number of retained hostages. But this decree was not applied. The Commune tried several times to exchange Mgr Darboy

Georges Darboy

Georges Darboy was a French Catholic priest, later bishop of Nancy then archbishop of Paris. He was among a group of prominent hostages executed as the Paris Commune of 1871 was about to be overthrown....

, archbishop of Paris, for Auguste Blanqui, but flatly refused and his personal secretary, Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire was a French philosopher, journalist, statesman, and possible illegitimate son of Napoleon I of France.- Biography :...

, declared: "The hostages! The hostages! too bad for them (tant pis pour eux!)."

Finally, during the Bloody Week and the ensuing executions by Versaille troops, Théophile Ferré

Théophile Ferré

Théophile Charles Gilles Ferré, was one of the members of the Paris Commune. He, together with Louis Rossel and Bourgeois, was one of the first to be executed at Satory, the military base south-west of Versailles....

signed the execution order for 6 hostages (including Mgr Darboy), who were executed by firing squad on May 24 in the prison de la Roquette. This led Auguste Vermorel

August Jean-Marie Vermorel

August Jean-Marie Vermorel was a French journalist.He was born at Denice.A radical and socialist, he was attached to the staff of the Presse and the Liberte . In the latter year he was appointed editor of the Courrier Français, and his attacks on the government in that organ led to his...

to ironically (and perhaps naively, since had refused any negotiation) declare: "What a great job! Now we've lost our only chance to stop the bloodshed." Ferré was himself executed in retaliation by ' troops.

La Semaine Sanglante

The toughest resistance came in the more working-class districts of the east, where fighting continued during the later stages of the week of vicious street fighting in what became known as La Semaine Sanglante ("The Bloody Week"). By May 27 only a few pockets of resistance remained, notably the poorer eastern districts of BellevilleBelleville, Paris

Belleville is a neighbourhood of Paris, France, parts of which lie in four different arrondissements. The major portion of Belleville straddles the borderline between the 20th arrondissement and the 19th along its main street, the Rue de Belleville...

and Ménilmontant

Ménilmontant

Ménilmontant is a neighbourhood of Paris, situated in the city's 20th arrondissement. It is affectionately known to locals as "Ménilmuche".-History:...

. Fighting ended during the late afternoon or early evening of May 28. According to legend, the last barricade was in the rue Ramponeau in Belleville.

Marshal MacMahon issued a proclamation: "To the inhabitants of Paris. The French army has come to save you. Paris is freed! At 4 o'clock our soldiers took the last insurgent position. Today the fight is over. Order, work and security will be reborn."

Reprisals now began in earnest. Having supported the Commune in any way was a political crime, of which thousands could be, and were, accused. Some Communards were shot against what is now known as the Communards' Wall

Communards' Wall

The Communards’ Wall at the Père Lachaise cemetery is where, on May 28, 1871, one-hundred forty-seven fédérés, combatants of the Paris Commune, were shot and thrown in an open trench at the foot of the wall....

in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the city of Paris, France , though there are larger cemeteries in the city's suburbs.Père Lachaise is in the 20th arrondissement, and is reputed to be the world's most-visited cemetery, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors annually to the...

while thousands of others were tried by summary courts martial of doubtful legality, and thousands shot. Notorious sites of slaughter were the Luxembourg Gardens and the Lobau Barracks, behind the Hôtel de Ville. Nearly 40,000 others were marched to Versailles for trials. For many days endless columns of men, women and children made a painful way under military escort to temporary prison quarters in Versailles. Later 12,500 were tried, and about 10,000 were found guilty: 23 men were executed; many were condemned to prison; 4,000 were deported for life to New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

. The number killed during La Semaine Sanglante can never be established for certain, and estimates vary from about 10,000 to 50,000. According to Benedict Anderson

Benedict Anderson

Benedict Richard O'Gorman Anderson is Aaron L. Binenkorb Professor Emeritus of International Studies, Government & Asian Studies at Cornell University, and is best known for his celebrated book Imagined Communities, first published in 1983...

, "7,500 were jailed or deported" and "roughly 20,000 executed."

One of the generals leading the counter-assault headed by was the Marquis de Galliffet, the fusilleur de la Commune who later took part as Minister of War

Minister of Defence (France)

The Minister of Defense and Veterans Affairs is the French government cabinet member charged with running the military of France....

in Waldeck-Rousseau's Government of Republican Defence at the turn of the century (alongside independent socialist Alexandre Millerand

Alexandre Millerand

Alexandre Millerand was a French socialist politician. He was President of France from 23 September 1920 to 11 June 1924 and Prime Minister of France 20 January to 23 September 1920...

).

Alfred Cobban

Alfred Cobban was a Professor of French History at University College, London, who along with prominent French historian Francois Furet held a 'Revisionist' view of the French Revolution.-Biography:...

, 30,000 were killed, perhaps as many as 50,000 later executed or imprisoned and 7,000 were exiled to New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

. Thousands more, including most of the Commune leaders, succeeded in escaping to Belgium, Britain (a safe haven for 3,000-4,000 refugees), Italy, Spain and the United States. The final exiles and transportees were amnestied in 1880. Some became prominent in later politics, as Paris councillors, deputies or senators. In 1872, "stringent laws were passed that ruled out all possibilities of organizing on the left." For the imprisoned there was a general amnesty in 1880, except for those convicted of assassination or arson. Paris remained under martial law for five years.

Retrospect

Karl MarxKarl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

found it aggravating that the Communards "lost precious moments" organising democratic elections rather than instantly finishing off Versailles once and for all. France's national bank, located in Paris and storing billions of francs, was left untouched and unguarded by the Communards. They asked to borrow money from the bank, which they got easily.

The Communards did take over the Paris mint and issued a 5 franc

Franc

The franc is the name of several currency units, most notably the Swiss franc, still a major world currency today due to the prominence of Swiss financial institutions and the former currency of France, the French franc until the Euro was adopted in 1999...

coin (identifiable by a trident mintmark) which is today quite scarce. However, they chose not to seize the national bank's assets because they were afraid that the world would condemn them if they did. Thus large amounts of money were moved from Paris to Versailles, money that financed the army that crushed the Commune.

Communists, left-wing socialists, anarchists and others have seen the Commune as a model for, or a prefiguration of, a liberated society, with a political system based on participatory democracy

Participatory democracy

Participatory Democracy, also known as Deliberative Democracy, Direct Democracy and Real Democracy , is a process where political decisions are made directly by regular people...

from the grass roots

Grass Roots

Grass Roots is an Australian television series produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation between 2000 and 2003.The series is set around the fictional Arcadia Waters Council near Sydney, and was primarily a satirical look at the machinations of local government...

up. Marx and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was a German industrialist, social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. In 1845 he published The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on personal observations and research...

, Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a well-known Russian revolutionary and theorist of collectivist anarchism. He has also often been called the father of anarchist theory in general. Bakunin grew up near Moscow, where he moved to study philosophy and began to read the French Encyclopedists,...

, and later Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

, Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

and Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

tried to draw major theoretical lessons (in particular as regards the "dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

" and the "withering away of the state") from the limited experience of the Commune. A more pragmatic lesson was drawn by the diarist Edmond de Goncourt

Edmond de Goncourt

Edmond de Goncourt , born Edmond Louis Antoine Huot de Goncourt, was a French writer, literary critic, art critic, book publisher and the founder of the Académie Goncourt.-Biography:...

, who wrote, three days after La Semaine Sanglante, "…the bleeding has been done thoroughly, and a bleeding like that, by killing the rebellious part of a population, postpones the next revolution… The old society has twenty years of peace before it…"

Karl Marx, in his important pamphlet The Civil War in France

The Civil War in France

The Civil War in France was a pamphlet written by Karl Marx as an official statement of the General Council of the International on the character and significance of the struggle of the Parisian Communards in the French Civil War of 1871....

(1871), written during the Commune, praised the Commune's achievements, and described it as the prototype for a revolutionary government of the future, "the form at last discovered" for the emancipation of the proletariat.

Marx wrote that: "Working men’s Paris, with its Commune, will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society. Its martyrs are enshrined in the great heart of the working class. Its exterminators' history has already nailed to that eternal pillory from which all the prayers of their priest will not avail to redeem them." .

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was a German industrialist, social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. In 1845 he published The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on personal observations and research...

echoed this idea, later maintaining that the absence of a standing army, the self-policing of the "quarters," and other features meant that the Commune was no longer a "state" in the old, repressive sense of the term: it was a transitional form, moving towards the abolition of the state as such—he used the famous term later taken up by Lenin and the Bolsheviks: the Commune was, he said, the first "dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

," meaning it was a state run by workers and in the interests of workers. But Marx and Engels were not entirely uncritical of the Commune. The split between the Marxists and anarchists at the 1872 Hague Congress

Hague Congress (1872)

The Hague Congress was the Fifth congress of the International Workingmen's Association held in in The Hague, Holland, which anarchists consider as null and void....

of the First International (IWA) may in part be traced to Marx's stance that the Commune might have saved itself had it dealt more harshly with reactionaries, instituted conscription, and centralized decision making in the hands of a revolutionary direction, etc. The other point of disagreement was the anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as a "political doctrine advocating the principle of absolute rule: absolutism, autocracy, despotism, dictatorship, totalitarianism." Anti-authoritarians usually believe in full equality before the law and strong civil...

socialists' oppositions to the Communist conception of conquest of power and of a temporary transitional state (the anarchists were in favor of general strike and immediate dismantlement of the state through the constitution of decentralized workers' councils as those seen in the commune).

The Paris Commune has been regarded with awe by many Leftist leaders. Mao

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

would refer to it often. Lenin, along with Marx, judged the Commune a living example of the "dictatorship of the proletariat," though Lenin criticized the Communards for having "stopped half way … led astray by dreams of … establishing a higher [capitalist] justice in the country … such institutions as the banks, for example, were not taken over"; he thought their "excessive magnanimity" had prevented them from "destroying" the class enemy. At his funeral, Lenin's body was wrapped in the remains of a red and white flag preserved from the Commune . The Soviet spaceflight Voskhod 1

Voskhod 1

Voskhod 1 was the seventh manned Soviet space flight. It achieved a number of "firsts" in the history of manned spaceflight, being the first space flight to carry more than one crewman into orbit, the first flight without the use of spacesuits, and the first to carry either an engineer or a...

carried part of a communard banner from the Paris Commune. Also, the Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

s renamed the dreadnought

Dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of 20th-century battleship. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts...

battleship

Battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of heavy caliber guns. Battleships were larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. As the largest armed ships in a fleet, battleships were used to attain command of the sea and represented the apex of a...

Sevastopol to Parizhskaya Kommuna.

Other Communes

Simultaneously with the Paris Commune, uprisings in LyonLyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

, Grenoble

Grenoble

Grenoble is a city in southeastern France, at the foot of the French Alps where the river Drac joins the Isère. Located in the Rhône-Alpes region, Grenoble is the capital of the department of Isère...

and other cities established equally short-lived Communes.

See also

Fictional treatments

- Among the first litterateur who wrote in favor of the Commune is Victor HugoVictor HugoVictor-Marie Hugo was a Frenchpoet, playwright, novelist, essayist, visual artist, statesman, human rights activist and exponent of the Romantic movement in France....

whose poem "Sur une barricade," written on June 11, 1871 and published in 1872 in a collection of poems under the name "L' Année terrible,"L'Année terribleL'Année terrible is a series of poems written by Victor Hugo and published in 1872. They deal with the Franco-Prussian War, the trauma of losing his son Charles, and with the Paris Commune...

honors the bravery of a twelve-year-old communard being led to the execution squad. - As well as innumerable novels (mainly in French), at least three plays have been set in the Commune: Nederlaget by Nordahl Grieg, Die Tage der CommuneThe Days of the CommuneThe Days of the Commune is a play by the twentieth-century German dramatist Bertolt Brecht. It dramatises the rise and fall of the Paris Commune in 1871. The play is an adaptation of the 1937 play The Defeat by the Norwegian poet and dramatist Nordahl Grieg...

by Bertolt BrechtBertolt BrechtBertolt Brecht was a German poet, playwright, and theatre director.An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the...

, and Le Printemps 71 by Arthur AdamovArthur AdamovArthur Adamov was a playwright, one of the foremost exponents of the Theatre of the Absurd.Adamov was born in Kislovodsk in Russia to a wealthy Armenian family, which lost its wealth in 1917...

. - There have been numerous films set in the Commune. Particularly notable is La Commune (Paris, 1871)La Commune (Paris, 1871)La Commune is a 2000 historical drama film directed by Peter Watkins about the Paris Commune. It is a historical re-enactment in the style of a documentary, and was shot in just 13 days in an abandoned factory on the outskirts of Paris...

, which runs for 5¾ hours and was directed by Peter WatkinsPeter WatkinsPeter Watkins is an English film and television director. He was born in Norbiton, Surrey, lived in Sweden, Canada and Lithuania for many years, and now lives in France. He is one of the pioneers of docudrama. His movies, pacifist and radical, strongly review the limit of classic documentary and...

. It was made in MontmartreMontmartreMontmartre is a hill which is 130 metres high, giving its name to the surrounding district, in the north of Paris in the 18th arrondissement, a part of the Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for the white-domed Basilica of the Sacré Cœur on its summit and as a nightclub district...

in 2000, and as with most of Watkins' other films it uses ordinary people instead of actors in order to create a documentary effect. The New BabylonThe New BabylonThe New Babylon is a 1929 silent film written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg...

(1929) was the recipient of Dmitri ShostakovichDmitri ShostakovichDmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Soviet Russian composer and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century....

's first film score. - The Italian composer, Luigi NonoLuigi NonoLuigi Nono was an Italian avant-garde composer of classical music and remains one of the most prominent composers of the 20th century.- Early years :Born in Venice, he was a member of a wealthy artistic family, and his grandfather was a notable painter...

, also wrote an opera Al gran sole carico d'amore (In the Bright Sunshine, Heavy with Love) that is based on the Paris Commune. - The discovery of a body from the Paris Commune buried in the Opera led Gaston LerouxGaston LerouxGaston Louis Alfred Leroux was a French journalist and author of detective fiction.In the English-speaking world, he is best known for writing the novel The Phantom of the Opera , which has been made into several film and stage productions of the same name, notably the 1925 film starring Lon...

to write the tale of Le Fantôme de l’OpéraThe Phantom of the OperaLe Fantôme de l'Opéra is a novel by French writer Gaston Leroux. It was first published as a serialisation in "Le Gaulois" from September 23, 1909 to January 8, 1910...

. - The title character of Karen BlixenKaren BlixenBaroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke , , née Karen Christenze Dinesen, was a Danish author also known by her pen name Isak Dinesen. She also wrote under the pen names Osceola and Pierre Andrézel...

's Babette's FeastBabette's FeastBabette's Feast is a 1987 Danish film directed by Gabriel Axel. The film's screenplay was written by Axel based on the story by Isak Dinesen , who also wrote the story which inspired the 1985 Academy Award winning film Out of Africa...

was a Communard and political refugee, forced to flee France after her husband and sons were killed. - Soviet filmmakers Grigori KozintsevGrigori KozintsevGrigori Mikhaylovich Kozintsev was a Jewish Ukrainian, Soviet Russian theatre and film director. He was named People's Artist of the USSR in 1964.He studied in the Imperial Academy of Arts...

and Leonid TraubergLeonid TraubergLeonid Zakharovich Trauberg was a Jewish Ukrainian Soviet film director and screenwriter. He directed 17 films between 1924 and 1961 and was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1941.-Filmography:* The Adventures of Oktyabrina ...

wrote and directed in 1929 the silent film The New BabylonThe New BabylonThe New Babylon is a 1929 silent film written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg...

(Novyy Vavilon) about the Paris Commune. - Terry PratchettTerry PratchettSir Terence David John "Terry" Pratchett, OBE is an English novelist, known for his frequently comical work in the fantasy genre. He is best known for his popular and long-running Discworld series of comic fantasy novels...

's Night Watch features a storyline based on the Paris Commune, in which a huge part of a city is slowly put behind barricades, at which point a brief civil war ensues. - The rise and fall of the Paris Commune was depicted in the novel SpangleSpangle (novel)Spangle is a historical novel written by Gary Jennings and first published in 1987.-Plot introduction:After surrendering at Appomattox Court House in Virginia at the end of the American Civil War, two Confederate soldiers meet and join Florian’s Flourishing Florilegium of Wonders, a traveling...

by Gary JenningsGary JenningsGary Jennings was an American author who wrote children's and adult novels. In 1980, after the successful novel Aztec, he specialized in writing adult historical fiction novels.-Biography:...

. - Berlin performance group Showcase Beat le Mot created Paris 1871 Bonjour Commune (first performed at Hebbel am Ufer in 2010), the final part of a tetralogy dealing with failed revolutions.

- French writer Jean VautrinJean VautrinJean Vautrin, Jean Vautrin, (John Herman) Jean Vautrin, (John Herman) (born May 17, 1933 Pagny-sur-Moselle is a French writer, filmmaker, and screenwriter.-Life:After studying literature at Auxerre, he took first place in the Id'HEC competition. He studied French literature at the University of...

's Le Cri du Peuple deals with the rise and fall of the Commune. Comics artist Jacques TardiJacques TardiJacques Tardi is a French comics artist, born 30 August 1946 in Valence, Drôme. He is often credited solely as Tardi.-Biography:After graduating from the École nationale des Beaux-Arts de Lyon and the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris, he started writing comics in 1969, at the...

translated the novel into a comic, which is also called Le Cri du Peuple. - In Fire on the Mountain by the American author Terry BissonTerry BissonTerry Ballantine Bisson is an American science fiction and fantasy author best known for his short stories...

, African Americans began a slave rebellion throughout the south after John Brown'sJohn Brown (abolitionist)John Brown was an American revolutionary abolitionist, who in the 1850s advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to abolish slavery in the United States. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre during which five men were killed, in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas, and made his name in the...

successful raid on Harpers Ferry. Along with many other nations, the Paris Commune was a successful socialist state.

External links

- Paris Commune Archive at marxists.org

- Paris Commune Archive at Anarchist Archive

- Norman Barth writing on the Commune in Paris Kiosque

- Discussion of the Commune in "An Anarchist FAQ"

- Short history of the Paris Commune on libcom.org

- Karl Marx's contemporary account of the Commune 'The Civil War in France'

- Karl Marx and the Paris Commune by C.L.R. James

- The Paris Commune and Marx' Theory of Revolution by Paul Dorn

- Association Les Amis de la Commune de Paris (1871) (in French)

- The Siege of The Paris Commune at the Northwestern UniversityNorthwestern UniversityNorthwestern University is a private research university in Evanston and Chicago, Illinois, USA. Northwestern has eleven undergraduate, graduate, and professional schools offering 124 undergraduate degrees and 145 graduate and professional degrees....

Library Mccormick Library of Special Collections - Paris Commune on Encyclopedia.com

- Page describing the history and the workings of the Paris Commune's government

- "The Paris Commune, Marxism and Anarchism" Article discussing the Paris Commune from an anarchist perspective (Anarcho-Syndicalist Review, no. 50)