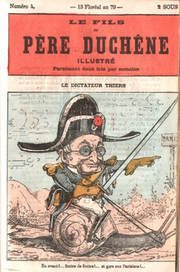

Adolphe Thiers

Encyclopedia

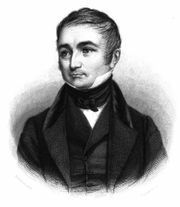

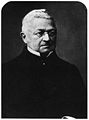

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers (lwi adɔlf tjɛʁ; 1797 – 1877) was a French politician and historian. was a prime minister under King Louis-Philippe of France

. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire

he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune

of 1871. From 1871 to 1873 he served initially as Head of State (effectively a provisional President of France), then provisional President. When, following a vote of no confidence in the National Assembly

, his offer of resignation was accepted (he had expected a rejection) he was forced to vacate the office. He was replaced as Provisional President by Patrice de Mac-Mahon, Duke of Magenta, who became full President of the Republic, a post had coveted, in 1875 when a series of constitutional laws officially creating the Third Republic were enacted.

, of Greek

origins. His family was somewhat grandiloquently spoken of as "cloth merchant

s ruined by the Revolution

", but it seems that at the actual time of his birth his father was a locksmith. His mother belonged to the family of the Chéniers

, and he was well educated, first at the lycée of Marseille, and then in the faculty of law at Aix-en-Provence

. Here he began his lifelong friendship with François Mignet, and was called to the bar at the age of twenty-three. He had, however, little taste for law and much for literature; and he obtained an academic prize at Aix for a discourse on the marquis de Vauvenargues

. In the early autumn of 1821 went to Paris, and was quickly introduced as a contributor to the Le Constitutionnel

. In each of the years immediately following his arrival in Paris he collected and published a volume of his articles, the first on the salon

of 1822, the second on a tour in the Pyrenees

. He was put out of all need of money by the singular benefaction of Johann Friedrich Cotta

, the well-known Stuttgart

publisher, who was part-proprietor of the Constitutionnel, and made over to his dividends, or part of them.

Meanwhile, he became very well known in Liberal society, and he had begun the celebrated Histoire de la revolution française, which founded his literary and helped his political fame. The first two volumes appeared in 1823, the last two (of ten) in 1827. The book brought him little profit at first, but became immensely popular. The well-known sentence of Thomas Carlyle

, that it is "as far as possible from meriting its high reputation", is in strictness justified, for all ' historical work is marked by extreme inaccuracy, by prejudice which passes the limits of accidental unfairness, and by an almost complete indifference to the merits as compared with the successes of his heroes. But Carlyle himself admits that is "a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing." Coming as the book did just when the reaction against the Revolution was about to turn into another reaction in its favour, it was assured of success.

For a moment it seemed as if had definitely chosen the lot of a literary man, not to say of a literary hack. He even planned an Histoire générale. But the accession to power of the Polignac

For a moment it seemed as if had definitely chosen the lot of a literary man, not to say of a literary hack. He even planned an Histoire générale. But the accession to power of the Polignac

ministry in August 1829 made him change his plans, and at the beginning of the next year , with Armand Carrel

, Mignet, Auguste Sautelet and others started the National

, a new opposition newspaper. himself was one of the animators of the 1830 revolution, being credited with "overcoming the scruples of Louis Philippe," perhaps no Herculean

task. At any rate, he received his reward. He ranked as one of the Radical supporters of the new dynasty, in opposition to the party of which his rival François Guizot

was the chief literary man, and Guizot's patron, the duc de Broglie, the main pillar. At first , though elected deputy for Aix, received only subordinate posts in the ministry of finance.

After the overthrow of his patron Jacques Laffitte

, he became much less radical, and after the troubles of June 1832 he was appointed to the ministry of the interior. He repeatedly changed portfolios, but remained in office for four years, became president of the council and, in effect, Prime Minister, in which capacity he began his series of quarrels and jealousies with François Guizot. After 1833, his career was bolstered by his marriage, as he secured financial backing from his nouveau riche patrons (in exchange for their place in the state officialdom and high society). At the time of his resignation in 1836 he was foreign minister and, as usual, favoured an energetic policy toward Spain, which he could not carry out.

He travelled in Italy

for some time, and it was not till 1838 that he began a regular campaign of parliamentary opposition, which in March 1840 made him president of the council and foreign minister for the second time, during which time he initiated the return of Napoleon's remains to France

in 1840. His policy of support for Muhammad Ali

of Egypt

in the Eastern crisis of that year led France to the brink of war with the other great powers. This resulted in his dismissal by the king, who did not wish for war. now had little to do with politics for some years, and spent his time on his Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, the first volume of which appeared in 1845.

Though he was still a member of the chamber, he spoke rarely, till after the beginning of 1846, when he was evidently bidding once more for power as the leader of the opposition group of the Center-Left. He then became a liberal opponent of the July Monarchy and again turned to writing, beginning his History of the Consulate and the Empire (20 vol., 1845–62; tr. 1845–62). In the midst of the February Revolution of 1848, Louis Philippe offered him the title of premier, but he refused, and both king and Thiers were soon swept aside by the revolutionary tide. Elected (1848) to the constituent assembly, Thiers was a leader of the right-wing liberals and bitterly opposed the socialists.

Immediately before the February revolution he went to all but the greatest lengths, and when it broke out he and Odilon Barrot

, the leader of the Dynastic Left, were summoned by the king; but it was too late. was unable to govern the forces he had helped to gather, and he resigned.

as president, was often and sharply criticized, one of the criticisms leading to a duel with a fellow-deputy, Nino Bixio. He had an important role in the shaping of the Falloux Laws

of 1850, which strongly increased the Catholic clergy's influence on the education system.

Thiers was then arrested during the December 1851 coup d'état

and sent to Mazas

prison, before being escorted out of France. But in the following summer he was allowed to return. His history for the next decade is almost a blank, his time being occupied for the most part on The Consulate and the Empire. It was not until 1863 that he re-entered political life, being elected by a Parisian constituency. For the seven years following he was the chief speaker among the small group of anti-Imperialists in the French chamber and was regarded generally as the most formidable enemy of the Empire. While protesting against its foreign enterprises, he also harped on French loss of prestige, and so helped contribute to stir up the fatal spirit which brought on the war of 1870.

In the diplomatic crisis of 1870, was one of the few who strongly opposed war with Prussia

In the diplomatic crisis of 1870, was one of the few who strongly opposed war with Prussia

, and was accused of lack of patriotism. But when France's armies suffered defeat after defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

(all within a period of a few weeks), 's earlier stance was vindicated. He urged early peace negotiations, and refused to take part in the new republican Government of National Defense

, which was determined to continue the war.

In the latter part of September and the first three weeks of October,1870 he went on a tour of Britain, Italy, Austria and Russia in the hope of obtaining an intervention, or at least some mediation. The mission was unsuccessful, as was his attempt to persuade Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck and the Government of National Defence to negotiate.

In the latter part of September and the first three weeks of October,1870 he went on a tour of Britain, Italy, Austria and Russia in the hope of obtaining an intervention, or at least some mediation. The mission was unsuccessful, as was his attempt to persuade Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck and the Government of National Defence to negotiate.

When the French government was finally forced to surrender, triumphantly re-entered the political scene. In national elections, he was elected in twenty-six departments; on 17 February 1871 was elected head of a provisional government, nominally "chef du pouvoir exécutif de la République en attendant qu'il soit statué sur les institutions de la France" (head of the executive power of the Republic until the institutions of France are decided). He succeeded in convincing the deputies that the peace was necessary, and on 1 March 1871 it was voted for by a margin of more than five to one.

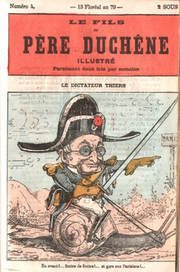

On 18 March, a major insurrection began in Paris after ordered the army to remove several hundred cannons in the possession of the Paris National Guard. evacuated his government and troops to Versailles. Parisians elected a radical republican and socialist city government on 26 March, entitled the Paris Commune

.

Fighting broke out between government troops and the those of the Commune early in April. Neither side was willing to negotiate, and fighting continued throughout April and May in the city's suburbs. On 21 May, government forces broke through the city's defences, and a week of street fighting, known as 'la Semaine Sanglante' (Bloody Week) began. Thousands of Parisians were killed in the fighting or summarily executed by courts martial. has often been accused of ordering this massacre – probably the worst in Europe between the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution of 1917 – but more likely he washed his hands of a massacre carried out by the army, thinking that it was a 'lesson' that the insurgents deserved. insisted on using legal means to prosecute the thousands of prisoners taken by the army, and over 12,000 were tried by special courts martial; of these 23 were executed, and over 4,000 transported to New Caledonia

, from where the last prisoners were amnestied in 1880. This severe repression has always been blamed principally on , and has overshadowed his memory in France and more generally on the political Left.

were born in the 19th century (Bonaparte in 1808 and Trochu in 1825).

His strong personal will and inflexible opinions had much to do with the resurrection of France; but the very same facts made it inevitable that he should excite violent opposition. He was a confirmed protectionist, and free trade

ideas had made great headway in France under the Empire; he was an advocate of long military service, and the devotees of la revanche (the revenge) were all for the introduction of general and compulsory but short service. Both his talents and his temper made him utterly indisposed to maintain the attitude supposed to be incumbent on a republican president; and his tongue was never carefully governed. In January 1872 he formally tendered his resignation; and though it was refused, almost all parties disliked him, while his chief supporters, men like Charles de Rémusat

, Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

and Jules Simon

were men rather of the past than of the present.

The year 1873, a parliamentary year in France, was occupied to a great extent with attacks on , essentially by the royalist majority in the National Assembly, who suspected, correctly, that was putting the weight of his enormous popularity among the electorate at the service of a future republic, which he famously described as 'the government that divides us least'. In the early spring, regulations were proposed and, on 13 April, carried, intended to restrict the executive, and especially the parliamentary, powers of the president, who was no longer to be allowed to speak in the Assembly. On 27 April a contested election in Paris, resulting in the return of a radical republican candidate, Barodet, was regarded as a grave disaster for the government, because it convinced the royalists that France was moving too far to the Left. The principal royalist leader, the Duc de Broglie, proposed a motion of no confidence in the government, which was carried by sixteen votes in a house of 704. at once resigned (24 May), expecting that he would have his resignation rescinded or that he would be immediately re-elected. To his shock the resignation was accepted and a professional soldier, Marshal Patrice de Mac-Mahon, was elected to the provisional presidency instead.

The year 1873, a parliamentary year in France, was occupied to a great extent with attacks on , essentially by the royalist majority in the National Assembly, who suspected, correctly, that was putting the weight of his enormous popularity among the electorate at the service of a future republic, which he famously described as 'the government that divides us least'. In the early spring, regulations were proposed and, on 13 April, carried, intended to restrict the executive, and especially the parliamentary, powers of the president, who was no longer to be allowed to speak in the Assembly. On 27 April a contested election in Paris, resulting in the return of a radical republican candidate, Barodet, was regarded as a grave disaster for the government, because it convinced the royalists that France was moving too far to the Left. The principal royalist leader, the Duc de Broglie, proposed a motion of no confidence in the government, which was carried by sixteen votes in a house of 704. at once resigned (24 May), expecting that he would have his resignation rescinded or that he would be immediately re-elected. To his shock the resignation was accepted and a professional soldier, Marshal Patrice de Mac-Mahon, was elected to the provisional presidency instead.

He survived, after his fall, for four years, continuing to sit in the Assembly and, after the dissolution of 1876, in the Chamber of Deputies, and sometimes, though rarely, speaking. He was also, on the occasion of this dissolution, elected senator

He survived, after his fall, for four years, continuing to sit in the Assembly and, after the dissolution of 1876, in the Chamber of Deputies, and sometimes, though rarely, speaking. He was also, on the occasion of this dissolution, elected senator

for Belfort

, which his exertions had saved for France; but he preferred the lower house, where he sat as of old for Paris. On 16 May 1877, he was one of the "363" who voted for no confidence in the Broglie ministry (thus paying his debts), and he took a considerable part in organizing the subsequent electoral campaign as an ally of the Republicans. But he was not to see its success, suffering a fatal stroke at St. Germain-en-Laye on 3 September.

Thiers was buried in Cimetière du Père Lachaise, an ironic resting place since one of the bloodiest battles of the Commune took place within the cemetery walls. Annually, the French Left

holds a ceremony at the Communards' Wall

to mark the anniversary of the occasion. Thiers' tomb has occasionally been the object of vandalism

.

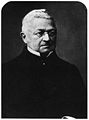

had long been married, and his wife and sister-in-law, Mlle Félicie Dosne, were his constant companions; but he left no children and had had only one, a daughter who long predeceased him. He had been a member of the Academy since 1834. His personal appearance was remarkable, and not imposing, for he was very short, with plain features, ungainly gestures and manners, very near-sighted, and of disagreeable voice; yet he became (after wisely giving up an attempt at the ornate style of oratory

) a very effective speaker in a kind of conversational manner, and in the epigram

of debate he had no superior among the statesmen of his time except Lord Beaconsfield

.

was by far the most gifted and interesting of the group of literary statesmen which formed a unique feature in the French political history of the 19th century. There are only two who are at all comparable to him, Guizot and Lamartine; and as a statesman he stands far above both. Nor is this eminence merely due to his great opportunity in 1870; for Guizot might under Louis Philippe have almost made himself a French Robert Walpole

, at least a French Palmerston

, and Lamartine's opportunities after 1848 were, for a man of political genius, unlimited. But both failed; Lamartine almost ludicrously, whereas , under difficult conditions, achieved a striking if not a brilliant success. But even when the minister of a constitutional monarch his intolerance of interference or joint authority, his temper at once imperious and devious, his inveterate inclination towards underhand rivalry and cabals for power and place, showed themselves unfavourably. His constant tendency to inflame the aggressive and chauvinistic spirit of his country was not based on any sound estimate of the relative power and interests of France, and led his country more than once to the verge of a great calamity. In opposition, both under Louis Philippe and under the empire, and even to some extent in the last four years of his life, his worst qualities were always evident. But with all these drawbacks he conquered and will retain a place in what is perhaps the highest, as it is certainly the smallest, class of statesmen: the class of those to whom their country has had recourse in a great disaster, who have shown in bringing her through that disaster with constancy, courage, devotion and skill and have been rewarded by as much success as the occasion permitted.

As a man of letters is much less well known. He has not only the fault of diffuseness, which is common to so many of the best-known historians of his century, but others as serious or more so. The charge of dishonesty

As a man of letters is much less well known. He has not only the fault of diffuseness, which is common to so many of the best-known historians of his century, but others as serious or more so. The charge of dishonesty

is one never to be lightly made against men of such distinction as his, especially when their evident confidence in their own infallibility, their faculty of ingenious casuistry

, and the strength of will which makes them (unconsciously, no doubt) close their minds to all inconvenient facts and inferences. But it is certain that from ' treatment of the men of the first revolution to his treatment of the Battle of Waterloo

, constant, angry and well-supported protests against his unfairness were not lacking. Although his research was undoubtedly wide-ranging, its results are by no means always accurate, and even his admirers find inconsistencies in his style. These characteristics reappear (accompanied, however, by frequent touches of the epigrammatic power above mentioned, which seems to have come to the orator or journalist easier than to the historian) in his speeches, which after his death were collected in many volumes by his widow. Sainte-Beuve, whose notices of are generally kind, says of him, "M. sait tout, tranche tout, parle de tout," and this omniscience and "cocksureness" (to use the word of a British Prime Minister contemporary with this prime minister of France) are perhaps the chief pervading features both of the statesman and the man of letters.

His histories, in many different editions, and his speeches, as above, are easily accessible; his minor works and newspaper articles have not, we believe, been collected in any form. Several years after his death appeared Deux opuscules (1891) and Melanges inedits (1892), while Notes et souvenirs, 1870–73, were published in 1901 by "F. D.", his sister-in-law and constant companion, Mlle Dosne. Works on him, by Laya, de Mazade, his colleague and friend Jules Simon, and others, are numerous.

Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I was King of the French from 1830 to 1848 in what was known as the July Monarchy. His father was a duke who supported the French Revolution but was nevertheless guillotined. Louis Philippe fled France as a young man and spent 21 years in exile, including considerable time in the...

. Following the overthrow of the Second Empire

Second French Empire

The Second French Empire or French Empire was the Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870, between the Second Republic and the Third Republic, in France.-Rule of Napoleon III:...

he again came to prominence as the French leader who suppressed the revolutionary Paris Commune

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists and Marxists had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class during the Industrial Revolution...

of 1871. From 1871 to 1873 he served initially as Head of State (effectively a provisional President of France), then provisional President. When, following a vote of no confidence in the National Assembly

French National Assembly

The French National Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of France under the Fifth Republic. The upper house is the Senate ....

, his offer of resignation was accepted (he had expected a rejection) he was forced to vacate the office. He was replaced as Provisional President by Patrice de Mac-Mahon, Duke of Magenta, who became full President of the Republic, a post had coveted, in 1875 when a series of constitutional laws officially creating the Third Republic were enacted.

Birth and early life

's maternal grandmother was the sister of Élisabeth Santi-Lomaca, mother of André ChénierAndré Chénier

André Marie Chénier was a French poet, associated with the events of the French Revolution of which he was a victim. His sensual, emotive poetry marks him as one of the precursors of the Romantic movement...

, of Greek

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

origins. His family was somewhat grandiloquently spoken of as "cloth merchant

Merchant

A merchant is a businessperson who trades in commodities that were produced by others, in order to earn a profit.Merchants can be one of two types:# A wholesale merchant operates in the chain between producer and retail merchant...

s ruined by the Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

", but it seems that at the actual time of his birth his father was a locksmith. His mother belonged to the family of the Chéniers

Chéniers

Chéniers is a commune in the Creuse department in the Limousin region in central France.-Geography:An area of forestry and farming comprising the village and several hamlets, situated in the valley of the Petite Creuse river, some north of Guéret at the junction of the D46 and the D48...

, and he was well educated, first at the lycée of Marseille, and then in the faculty of law at Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence

Aix , or Aix-en-Provence to distinguish it from other cities built over hot springs, is a city-commune in southern France, some north of Marseille. It is in the region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, in the département of Bouches-du-Rhône, of which it is a subprefecture. The population of Aix is...

. Here he began his lifelong friendship with François Mignet, and was called to the bar at the age of twenty-three. He had, however, little taste for law and much for literature; and he obtained an academic prize at Aix for a discourse on the marquis de Vauvenargues

Luc de Clapiers, marquis de Vauvenargues

Luc de Clapiers, marquis de Vauvenargues was a minor French writer, a moralist. He died at age 31, in broken health, having published the year prior—anonymously—a collection of essays and aphorisms with the encouragement of Voltaire, his friend. He first received public notice under his own name...

. In the early autumn of 1821 went to Paris, and was quickly introduced as a contributor to the Le Constitutionnel

Le Constitutionnel

Le Constitutionnel was a French political and literary newspaper, founded in Paris during the Hundred Days by Joseph Fouché. Originally established in October 1815 as The Independent, it took its current name during the Second Restoration. A voice for Liberals, Bonapartists, and critics of the...

. In each of the years immediately following his arrival in Paris he collected and published a volume of his articles, the first on the salon

Paris Salon

The Salon , or rarely Paris Salon , beginning in 1725 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. Between 1748–1890 it was the greatest annual or biannual art event in the Western world...

of 1822, the second on a tour in the Pyrenees

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees is a range of mountains in southwest Europe that forms a natural border between France and Spain...

. He was put out of all need of money by the singular benefaction of Johann Friedrich Cotta

Johann Friedrich Cotta

Johann Friedrich, Freiherr Cotta von Cottendorf was a German publisher, industrial pioneer and politician.- Ancestors :Cotta is the name of a family of German publishers, intimately...

, the well-known Stuttgart

Stuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

publisher, who was part-proprietor of the Constitutionnel, and made over to his dividends, or part of them.

Meanwhile, he became very well known in Liberal society, and he had begun the celebrated Histoire de la revolution française, which founded his literary and helped his political fame. The first two volumes appeared in 1823, the last two (of ten) in 1827. The book brought him little profit at first, but became immensely popular. The well-known sentence of Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle was a Scottish satirical writer, essayist, historian and teacher during the Victorian era.He called economics "the dismal science", wrote articles for the Edinburgh Encyclopedia, and became a controversial social commentator.Coming from a strict Calvinist family, Carlyle was...

, that it is "as far as possible from meriting its high reputation", is in strictness justified, for all ' historical work is marked by extreme inaccuracy, by prejudice which passes the limits of accidental unfairness, and by an almost complete indifference to the merits as compared with the successes of his heroes. But Carlyle himself admits that is "a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing." Coming as the book did just when the reaction against the Revolution was about to turn into another reaction in its favour, it was assured of success.

July Monarchy of King Louis-Philippe

Jules, prince de Polignac

Prince Jules de Polignac, 3rd Duke of Polignac , was a French statesman. He played a part in ultra-royalist reaction after the Revolution...

ministry in August 1829 made him change his plans, and at the beginning of the next year , with Armand Carrel

Armand Carrel

Armand Carrel was a French journalist and political writer.-Biography:Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Armand Carrel was born at Rouen. His father was a wealthy merchant, and he received a liberal education at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen. , afterwards attending the military school at St Cyr...

, Mignet, Auguste Sautelet and others started the National

Le National (newspaper)

Le National was a French daily founded in 1830 by Adolphe Thiers, Armand Carrel, François-Auguste Mignet and the librarian-editor Auguste Sautelet, as the mouthpiece of the liberal opposition to the Second Restoration....

, a new opposition newspaper. himself was one of the animators of the 1830 revolution, being credited with "overcoming the scruples of Louis Philippe," perhaps no Herculean

Hercules

Hercules is the Roman name for Greek demigod Heracles, son of Zeus , and the mortal Alcmene...

task. At any rate, he received his reward. He ranked as one of the Radical supporters of the new dynasty, in opposition to the party of which his rival François Guizot

François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848, a conservative liberal who opposed the attempt by King Charles X to usurp legislative power, and worked to sustain a constitutional...

was the chief literary man, and Guizot's patron, the duc de Broglie, the main pillar. At first , though elected deputy for Aix, received only subordinate posts in the ministry of finance.

After the overthrow of his patron Jacques Laffitte

Jacques Laffitte

Jacques Laffitte was a French banker and politician.-Biography:Laffitte was born at Bayonne, one of the ten children of a carpenter....

, he became much less radical, and after the troubles of June 1832 he was appointed to the ministry of the interior. He repeatedly changed portfolios, but remained in office for four years, became president of the council and, in effect, Prime Minister, in which capacity he began his series of quarrels and jealousies with François Guizot. After 1833, his career was bolstered by his marriage, as he secured financial backing from his nouveau riche patrons (in exchange for their place in the state officialdom and high society). At the time of his resignation in 1836 he was foreign minister and, as usual, favoured an energetic policy toward Spain, which he could not carry out.

He travelled in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

for some time, and it was not till 1838 that he began a regular campaign of parliamentary opposition, which in March 1840 made him president of the council and foreign minister for the second time, during which time he initiated the return of Napoleon's remains to France

Retour des cendres

The retour des cendres was the return of the mortal remains of Napoleon I of France from the island of St Helena to France and their burial in the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris in 1840, on the initiative of Adolphe Thiers and King Louis-Philippe.-Previous attempts:In a codicil to his will, written...

in 1840. His policy of support for Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha was a commander in the Ottoman army, who became Wāli, and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan...

of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

in the Eastern crisis of that year led France to the brink of war with the other great powers. This resulted in his dismissal by the king, who did not wish for war. now had little to do with politics for some years, and spent his time on his Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, the first volume of which appeared in 1845.

Though he was still a member of the chamber, he spoke rarely, till after the beginning of 1846, when he was evidently bidding once more for power as the leader of the opposition group of the Center-Left. He then became a liberal opponent of the July Monarchy and again turned to writing, beginning his History of the Consulate and the Empire (20 vol., 1845–62; tr. 1845–62). In the midst of the February Revolution of 1848, Louis Philippe offered him the title of premier, but he refused, and both king and Thiers were soon swept aside by the revolutionary tide. Elected (1848) to the constituent assembly, Thiers was a leader of the right-wing liberals and bitterly opposed the socialists.

Immediately before the February revolution he went to all but the greatest lengths, and when it broke out he and Odilon Barrot

Odilon Barrot

Camille Hyacinthe Odilon Barrot was a French politician.-Early life:Barrot was born at Villefort Lozère. He belonged to a legal family, his father, an advocate of Toulouse, having been a member of the Convention who had voted against the death of Louis XVI. Odilon Barrot's earliest recollections...

, the leader of the Dynastic Left, were summoned by the king; but it was too late. was unable to govern the forces he had helped to gather, and he resigned.

Second Republic and the Second Empire

Under the Republic he took up the position of conservative republican, which he ever afterwards maintained, and he never took office. But the consistency of his conduct, especially in voting for Louis NapoleonNapoleon III of France

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was the President of the French Second Republic and as Napoleon III, the ruler of the Second French Empire. He was the nephew and heir of Napoleon I, christened as Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte...

as president, was often and sharply criticized, one of the criticisms leading to a duel with a fellow-deputy, Nino Bixio. He had an important role in the shaping of the Falloux Laws

Falloux Laws

The Falloux Laws were voted during the French Second Republic and promulgated on 15 March 1850 and in 1851, following the presidential election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in December 1848 and the May 1849 legislative elections that gave a majority to the conservative Parti de l'Ordre. Named for...

of 1850, which strongly increased the Catholic clergy's influence on the education system.

Thiers was then arrested during the December 1851 coup d'état

French coup of 1851

The French coup d'état on 2 December 1851, staged by Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte , ended in the successful dissolution of the French National Assembly, as well as the subsequent re-establishment of the French Empire the next year...

and sent to Mazas

Mazas

Mazas may refer to:* Mazas Prison, a 19th-century French prison* Rafael Sánchez Mazas, a Spanish writer and member of Franco's Falange movement.* Jacques-Fereol Mazas, a French violinist...

prison, before being escorted out of France. But in the following summer he was allowed to return. His history for the next decade is almost a blank, his time being occupied for the most part on The Consulate and the Empire. It was not until 1863 that he re-entered political life, being elected by a Parisian constituency. For the seven years following he was the chief speaker among the small group of anti-Imperialists in the French chamber and was regarded generally as the most formidable enemy of the Empire. While protesting against its foreign enterprises, he also harped on French loss of prestige, and so helped contribute to stir up the fatal spirit which brought on the war of 1870.

Collapse of the Empire and the Paris Commune

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, and was accused of lack of patriotism. But when France's armies suffered defeat after defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

(all within a period of a few weeks), 's earlier stance was vindicated. He urged early peace negotiations, and refused to take part in the new republican Government of National Defense

Government of National Defense

Le Gouvernement de la Défense Nationale, or The Government of National Defence, was the first Government of the Third Republic of France from September 4, 1870, to February 13, 1871, during the Franco-Prussian War, formed after the Emperor Louis Napoleon III was captured by the Prussian army. The...

, which was determined to continue the war.

When the French government was finally forced to surrender, triumphantly re-entered the political scene. In national elections, he was elected in twenty-six departments; on 17 February 1871 was elected head of a provisional government, nominally "chef du pouvoir exécutif de la République en attendant qu'il soit statué sur les institutions de la France" (head of the executive power of the Republic until the institutions of France are decided). He succeeded in convincing the deputies that the peace was necessary, and on 1 March 1871 it was voted for by a margin of more than five to one.

On 18 March, a major insurrection began in Paris after ordered the army to remove several hundred cannons in the possession of the Paris National Guard. evacuated his government and troops to Versailles. Parisians elected a radical republican and socialist city government on 26 March, entitled the Paris Commune

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the split between anarchists and Marxists had taken place, and it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class during the Industrial Revolution...

.

Fighting broke out between government troops and the those of the Commune early in April. Neither side was willing to negotiate, and fighting continued throughout April and May in the city's suburbs. On 21 May, government forces broke through the city's defences, and a week of street fighting, known as 'la Semaine Sanglante' (Bloody Week) began. Thousands of Parisians were killed in the fighting or summarily executed by courts martial. has often been accused of ordering this massacre – probably the worst in Europe between the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution of 1917 – but more likely he washed his hands of a massacre carried out by the army, thinking that it was a 'lesson' that the insurgents deserved. insisted on using legal means to prosecute the thousands of prisoners taken by the army, and over 12,000 were tried by special courts martial; of these 23 were executed, and over 4,000 transported to New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

, from where the last prisoners were amnestied in 1880. This severe repression has always been blamed principally on , and has overshadowed his memory in France and more generally on the political Left.

Third Republic

On 30 August became the provisional president of the as-yet undeclared republic. He held office for more than two years after this event. (See note 1) was the only French President born in the 18th century. His two predecessors – Emperor Napoleon III (who served previously as President of the 2nd Republic from 1848 to 1854), and Interim President Louis Jules TrochuLouis Jules Trochu

Louis Jules Trochu was a French military leader and politician. He served as President of the Government of National Defense—France's de facto head of state—from 4 September 1870 until his resignation on 22 January 1871 .- Military career :He was born at Palais...

were born in the 19th century (Bonaparte in 1808 and Trochu in 1825).

His strong personal will and inflexible opinions had much to do with the resurrection of France; but the very same facts made it inevitable that he should excite violent opposition. He was a confirmed protectionist, and free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

ideas had made great headway in France under the Empire; he was an advocate of long military service, and the devotees of la revanche (the revenge) were all for the introduction of general and compulsory but short service. Both his talents and his temper made him utterly indisposed to maintain the attitude supposed to be incumbent on a republican president; and his tongue was never carefully governed. In January 1872 he formally tendered his resignation; and though it was refused, almost all parties disliked him, while his chief supporters, men like Charles de Rémusat

Charles de Rémusat

Charles François Marie, Comte de Rémusat , was a French politician and writer.-Biography:He was born in Paris. His father, Auguste Laurent, Comte de Rémusat, of a good family of Toulouse, was chamberlain to Napoleon Bonaparte, but acquiesced in the restoration and became prefect first of Haute...

, Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire

Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire was a French philosopher, journalist, statesman, and possible illegitimate son of Napoleon I of France.- Biography :...

and Jules Simon

Jules Simon

Jules François Simon was a French statesman and philosopher, and one of the leader of the Opportunist Republicans faction.-Biography:Simon was born at Lorient. His father was a linen-draper from Lorraine, who renounced Protestantism before his second marriage with a Catholic Breton. Jules Simon...

were men rather of the past than of the present.

Last years

French Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Parliament of France, presided over by a president.The Senate enjoys less prominence than the lower house, the directly elected National Assembly; debates in the Senate tend to be less tense and generally enjoy less media coverage.-History:France's first...

for Belfort

Belfort

Belfort is a commune in the Territoire de Belfort department in Franche-Comté in northeastern France and is the prefecture of the department. It is located on the Savoureuse, on the strategically important natural route between the Rhine and the Rhône – the Belfort Gap or Burgundian Gate .-...

, which his exertions had saved for France; but he preferred the lower house, where he sat as of old for Paris. On 16 May 1877, he was one of the "363" who voted for no confidence in the Broglie ministry (thus paying his debts), and he took a considerable part in organizing the subsequent electoral campaign as an ally of the Republicans. But he was not to see its success, suffering a fatal stroke at St. Germain-en-Laye on 3 September.

Thiers was buried in Cimetière du Père Lachaise, an ironic resting place since one of the bloodiest battles of the Commune took place within the cemetery walls. Annually, the French Left

Left-wing politics

In politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

holds a ceremony at the Communards' Wall

Communards' Wall

The Communards’ Wall at the Père Lachaise cemetery is where, on May 28, 1871, one-hundred forty-seven fédérés, combatants of the Paris Commune, were shot and thrown in an open trench at the foot of the wall....

to mark the anniversary of the occasion. Thiers' tomb has occasionally been the object of vandalism

Vandalism

Vandalism is the behaviour attributed originally to the Vandals, by the Romans, in respect of culture: ruthless destruction or spoiling of anything beautiful or venerable...

.

had long been married, and his wife and sister-in-law, Mlle Félicie Dosne, were his constant companions; but he left no children and had had only one, a daughter who long predeceased him. He had been a member of the Academy since 1834. His personal appearance was remarkable, and not imposing, for he was very short, with plain features, ungainly gestures and manners, very near-sighted, and of disagreeable voice; yet he became (after wisely giving up an attempt at the ornate style of oratory

Oratory

Oratory is a type of public speaking.Oratory may also refer to:* Oratory , a power metal band* Oratory , a place of worship* a religious order such as** Oratory of Saint Philip Neri ** Oratory of Jesus...

) a very effective speaker in a kind of conversational manner, and in the epigram

Epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, usually memorable and sometimes surprising statement. Derived from the epigramma "inscription" from ἐπιγράφειν epigraphein "to write on inscribe", this literary device has been employed for over two millennia....

of debate he had no superior among the statesmen of his time except Lord Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. Starting from comparatively humble origins, he served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom...

.

was by far the most gifted and interesting of the group of literary statesmen which formed a unique feature in the French political history of the 19th century. There are only two who are at all comparable to him, Guizot and Lamartine; and as a statesman he stands far above both. Nor is this eminence merely due to his great opportunity in 1870; for Guizot might under Louis Philippe have almost made himself a French Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

, at least a French Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

, and Lamartine's opportunities after 1848 were, for a man of political genius, unlimited. But both failed; Lamartine almost ludicrously, whereas , under difficult conditions, achieved a striking if not a brilliant success. But even when the minister of a constitutional monarch his intolerance of interference or joint authority, his temper at once imperious and devious, his inveterate inclination towards underhand rivalry and cabals for power and place, showed themselves unfavourably. His constant tendency to inflame the aggressive and chauvinistic spirit of his country was not based on any sound estimate of the relative power and interests of France, and led his country more than once to the verge of a great calamity. In opposition, both under Louis Philippe and under the empire, and even to some extent in the last four years of his life, his worst qualities were always evident. But with all these drawbacks he conquered and will retain a place in what is perhaps the highest, as it is certainly the smallest, class of statesmen: the class of those to whom their country has had recourse in a great disaster, who have shown in bringing her through that disaster with constancy, courage, devotion and skill and have been rewarded by as much success as the occasion permitted.

Dishonesty

Dishonesty is a word which, in common usage, may be defined as the act or to act without honesty. It is used to describe a lack of probity, cheating, lying or being deliberately deceptive or a lack in integrity, knavishness, perfidiosity, corruption or treacherousness...

is one never to be lightly made against men of such distinction as his, especially when their evident confidence in their own infallibility, their faculty of ingenious casuistry

Casuistry

In applied ethics, casuistry is case-based reasoning. Casuistry is used in juridical and ethical discussions of law and ethics, and often is a critique of principle- or rule-based reasoning...

, and the strength of will which makes them (unconsciously, no doubt) close their minds to all inconvenient facts and inferences. But it is certain that from ' treatment of the men of the first revolution to his treatment of the Battle of Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

, constant, angry and well-supported protests against his unfairness were not lacking. Although his research was undoubtedly wide-ranging, its results are by no means always accurate, and even his admirers find inconsistencies in his style. These characteristics reappear (accompanied, however, by frequent touches of the epigrammatic power above mentioned, which seems to have come to the orator or journalist easier than to the historian) in his speeches, which after his death were collected in many volumes by his widow. Sainte-Beuve, whose notices of are generally kind, says of him, "M. sait tout, tranche tout, parle de tout," and this omniscience and "cocksureness" (to use the word of a British Prime Minister contemporary with this prime minister of France) are perhaps the chief pervading features both of the statesman and the man of letters.

His histories, in many different editions, and his speeches, as above, are easily accessible; his minor works and newspaper articles have not, we believe, been collected in any form. Several years after his death appeared Deux opuscules (1891) and Melanges inedits (1892), while Notes et souvenirs, 1870–73, were published in 1901 by "F. D.", his sister-in-law and constant companion, Mlle Dosne. Works on him, by Laya, de Mazade, his colleague and friend Jules Simon, and others, are numerous.

Further reading

- François J. Le Goff. The life of Louis Adolphe Thiers (1879) online

- Paul de Rémusat. Thiers (1889) online in English translation

External links

- Site listing links to the Third Republic

- Page on history of French flags with brief outline of formation of the Third Republic