Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Encyclopedia

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet

foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov

and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow

in the late hours of 23 August 1939. It was a non-aggression pact

under which the Soviet Union

and Nazi Germany

each pledged to remain neutral

in the event that either nation were attacked by a third party. It remained in effect until 22 June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union

.

In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol dividing Northern

and Eastern Europe

into German and Soviet spheres of influence, anticipating potential "territorial and political rearrangements" of these countries. Thereafter, Germany and the Soviet Union invaded

, on September 1 and 17 respectively, their respective sides of Poland

, dividing the country between them. Part of eastern Finland

was annexed by the Soviet Union after the Winter War

. This was followed by Soviet annexation

s of Estonia

, Latvia

, Lithuania

, Bessarabia

, Northern Bukovina

and the Hertza region

.

was disastrous for both the German Reich

and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

. During the war, the Bolsheviks struggled for survival, and Lenin had no option except to recognize the independence of Finland

, Estonia

, Latvia

, Lithuania

and Poland

. Moreover, facing a German military advance, Lenin and Trotsky were forced to enter into the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

, which ceded some western Russian territory to the German Empire

. After Germany's collapse, British

, French

and Japan

ese troops intervened in the Russian Civil War

.

On 16 April 1922, Germany and Soviet Russia

entered the Treaty of Rapallo

, pursuant to which they renounced territorial and financial claims against each other. The parties further pledged neutrality in the event of an attack against one another with the 1926 Treaty of Berlin. While trade between the two countries fell sharply after World War I, trade agreements signed in the mid-1920s helped to increase trade to 433 million Reichsmarks per year by 1927.

At the beginning of the 1930s, the Nazi Party's rise to power increased tensions between Germany, the Soviet Union and other countries with ethnic Slavs, which were considered "Untermensch

en" according to Nazi racial ideology

. Moreover, the anti-Semitic Nazis associated ethnic Jews with both communism

and financial capitalism

, both of which they opposed

. Consequently, Nazi theory held that Slavs in the Soviet Union were being ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik

" masters. In 1934, Hitler himself had spoken of an inescapable battle against both Pan-Slavism

and Neo-Slavism, the victory in which would lead to "permanent mastery of the world", though he stated that they would "walk part of the road with the Russians, if that will help us." The resulting manifestation of German anti-Bolshevism and an increase in Soviet foreign debts caused German–Soviet trade to dramatically decline. Imports of Soviet goods to Germany fell to 223 million Reichsmarks in 1934 as the more isolationist Stalinist regime asserted power and the abandonment of post–World War I Treaty of Versailles

military controls decreased Germany's reliance on Soviet imports.

In 1936, Germany and Fascist Italy

supported Spanish Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War

, while the Soviets supported the partially socialist-led Second Spanish Republic

under the leadership of president Manuel Azaña

. Thus, in a sense, the Spanish Civil War became also the scene of a proxy war

between Germany and the USSR. In 1936, Germany and Japan entered the Anti-Comintern Pact

, and were joined a year later by Italy

.

Hitler's fierce anti-Soviet rhetoric was one of the reasons why the UK and France decided that Soviet participation in the 1938 Munich Conference regarding Czechoslovakia

would be both dangerous and useless. The Munich Agreement

that followed marked a partial German annexation

of Czechoslovakia in late 1938 followed by its complete dissolution in March 1939, which is seen as part of an appeasement

of Germany conducted by Chamberlain

's and Daladier's cabinets. This policy immediately raised the question of whether the Soviet Union could avoid being next on Hitler's list. The Soviet leadership believed that the West may want to encourage German aggression in the East and that France and Britain might stay neutral in a war initiated by Germany, hoping that the warring states would wear each other out and put an end to both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

For Germany, because an autarkic

economic approach or an alliance with Britain were impossible, closer relations with the Soviet Union to obtain raw materials became necessary, if not just for economic reasons alone. Moreover, an expected British blockade in the event of war would create massive shortages for Germany in a number of key raw materials. After the Munich agreement, the resulting increase in German military supply needs and Soviet demands for military machinery, talks between the two countries occurred from late 1938 to March 1939. The third Soviet Five Year Plan required massive new infusions of technology and industrial equipment.

On 31 March 1939, in response to Nazi Germany

's defiance of the Munich Agreement and occupation of Czechoslovakia, the United Kingdom

pledged the support of itself and France

to guarantee the independence of Poland, Belgium, Romania, Greece, and Turkey. On 6 April Poland and the UK agreed to formalize the guarantee as a military alliance, pending negotiations. On 28 April, Hitler denounced the 1934 German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact and the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement

.

Starting in mid-March 1939, the Soviet Union, Britain and France traded a flurry of suggestions and counterplans regarding a potential political and military agreement. Although informal consultations commenced in April, the main negotiations began only in May. At the same time, throughout the early 1939,Germany and the Soviet Union had discussed a possibility of an economic deal involving industrial equipment and armament for the USSR in exchange for raw materials needed for German war production. German war planners had estimated massive raw materials shortfalls if Germany entered a war without Soviet supply. For months, Germany had secretly hinted to Soviet diplomats that it could offer better terms for a political agreement than Britain and France.

The Soviet Union feared Western powers and the possibility of "capitalist encirclements", had little faith either that war could be avoided, or faith in the Polish army, and wanted nothing less than an ironclad military alliance that would provide a guaranteed support for a two-pronged attack on Germany. Britain and France believed that war could still be avoided, and that the Soviet Union, weakened by the Great Purge

, could not be a main military participant, a point that many military sources were at variance with, especially after the sound thrashing administered to the Japanese Kwantung army on the Manchurian frontier. France was more anxious to find an agreement with the USSR than was Britain; as a continental power, it was more willing to make concessions, more fearful of the dangers of an agreement between the USSR and Germany. These contrasting attitudes partly explain why the USSR has often been charged with playing a double game in 1939: carrying on open negotiations for an alliance with Britain and France while secretly considering propositions from Germany.

By the end of May drafts were formally presented. In mid-June the main Tripartite negotiations started. The discussion was focused on potential guarantees to central and east European countries should a German aggression arise. The USSR proposed to consider that a political turn towards Germany by the Baltic states

would constitute an "indirect aggression" towards the Soviet Union. Britain opposed such proposals, because they feared the Soviets' proposed language could justify a Soviet intervention in Finland and the Baltic states, or push those countries to seek closer relations with Germany. The discussion about a definition of "indirect aggression" became one of the sticking points between the parties, and by mid-July the tripartite political negotiations effectively stalled, while the parties agreed to start negotiations on a military agreement, which the Soviets insisted must be entered into simultaneously with any political agreement.

, who was regarded as pro-western and who was also Jewish, with Vyacheslav Molotov

, allowing the Soviet Union more latitude in discussions with more parties, not only with Britain and France.

In late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German officials agreed on most of the details for a planned economic agreement, and specifically addressed a potential political agreement, which the Soviets stated could only come after an economic agreement.

of both countries.

At the same time, Tripartite Soviet–British–French negotiators scheduled talks on military matters to occur in Moscow in August 1939, aiming to define the specifics of what should be the reaction of the Soviet Union, France and Britain, if they were to sign any agreement, in case a German attack occur. The tripartite military talks started in mid-August, hit a sticking point regarding passage of Soviet troops through Poland if Germans attacked, and the parties waited as British and French officials overseas pressured Polish officials to agree to such terms. Polish officials refused to allow Soviet troops on to Polish territory if Germans attacked; as Polish foreign minister Józef Beck

pointed out, they feared that once the Red Army entered their territories, it might never leave. While Britain and France refused to allow Soviet Union to impinge on the sovereignty of its neighbors, Germany possessed no such reservations.

On August 19, the 1939 German–Soviet Commercial Agreement was finally signed. On 21 August the Soviets suspended Tripartite military talks, citing other reasons. That same day, Stalin received assurance that Germany would approve secret protocols to the proposed non-aggression pact that would place half of Poland

(border along the Vistula river), Latvia

, Estonia

, Finland

, and Bessarabia

in the Soviets' sphere of influence. That night, Stalin replied that the Soviets were willing to sign the pact, and that he would receive Ribbentrop on 23 August.

Excerpt from the article “On Soviet-German Relations” on Soviet newspaper Izvestia

, August 21, 1939.

On 22 August, one day after the talks broke down with France and Britain, Moscow revealed that Ribbentrop would visit Stalin the next day. This happened while the Soviets were still negotiating with the British and French missions in Moscow. With the Western nations unwilling to accede to Soviet demands, Stalin instead entered a secret Nazi–Soviet alliance. On 24 August a 10-year non-aggression pact

On 22 August, one day after the talks broke down with France and Britain, Moscow revealed that Ribbentrop would visit Stalin the next day. This happened while the Soviets were still negotiating with the British and French missions in Moscow. With the Western nations unwilling to accede to Soviet demands, Stalin instead entered a secret Nazi–Soviet alliance. On 24 August a 10-year non-aggression pact

was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other."

Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern

Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern

and Eastern Europe

were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence". In the North, Finland

, Estonia

and Latvia

were assigned to the Soviet sphere. Poland was to be partitioned in the event of its "political rearrangement"—the areas east of the Pisa, Narev, Vistula

and San rivers going to the Soviet Union while Germany would occupy the west. Lithuania

, adjacent to East Prussia

, would be in the German sphere of influence, although a second secret protocol agreed to in September 1939 reassigned the majority of Lithuania to the USSR. According to the secret protocol, Lithuania would be granted the ethnic Polish city of Wilno, which was a part of Poland during the inter-war period. Another clause of the treaty was that Germany

would not interfere with the Soviet Union

's actions towards Bessarabia

, then part of Romania; as the result, Bessarabia was joined to the Moldovan ASSR, and become the Moldovan SSR under control of Moscow.

At the signing, Ribbentrop and Stalin enjoyed warm conversations, exchanged toasts and further addressed the prior hostilities between the countries in the 1930s. They characterized Britain as always attempting to disrupt Soviet-German relations, stated that the Anti-Comintern pact was not aimed at the Soviet Union, but actually aimed at Western democracies and "frightened principally the City of London [i.e., the British financiers] and the English shopkeepers."

On 24 August, Pravda

and Izvestia

carried news of the non-secret portions of the Pact, complete with the now infamous front-page picture of Molotov signing the treaty, with a smiling Stalin looking on (located at the top of this article). The news was met with utter shock and surprise by government leaders and media worldwide, most of whom were aware only of the British–French–Soviet negotiations that had taken place for months. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was received with shock by Nazi Germany’s allies, notably Japan, by the Comintern

and foreign communist parties, and by Jewish communities all around the world. So, that day, German diplomat Hans von Herwarth

, whose grandmother was Jewish, informed Guido Relli, an Italian diplomat, and American chargé d'affaires Charles Bohlen on the secret protocol regarding vital interests in the countries' allotted "spheres of influence", without revealing the annexation rights for "territorial and political rearrangement".

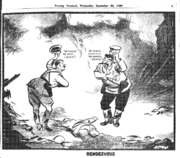

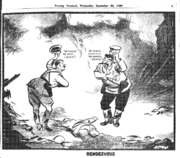

Time Magazine repeatedly referred to the Pact as the "Communazi Pact" and its participants as "communazis" until April 1941.

Soviet propaganda and representatives went to great lengths to minimize the importance of the fact that they had opposed and fought against the Nazis in various ways for a decade prior to signing the Pact. Upon signing the pact, Molotov tried to reassure the Germans of his good intentions by commenting to journalists that "fascism is a matter of taste". For its part, Nazi Germany also did a public volte-face

regarding its virulent opposition to the Soviet Union, though Hitler still viewed an attack on the Soviet Union as "inevitable".

Concerns over the possible existence of a secret protocol were first expressed by the intelligence organizations of the Baltic states scant days after the pact was signed. Speculation grew stronger when Soviet negotiators referred to its content during negotiations for military bases in those countries (see occupation of the Baltic States).

The day after the Pact was signed, the French and British military negotiation delegation urgently requested a meeting with Soviet military negotiator Kliment Voroshilov

. On August 25, Voroshilov told them "[i]n view of the changed political situation, no useful purpose can be served in continuing the conversation." That day, Hitler told the British ambassador to Berlin that the pact with the Soviets prevented Germany from facing a two front war, changing the strategic situation from that in World War I, and that Britain should accept his demands regarding Poland.

On 25 August, surprising Hitler, Britain entered into a defense pact with Poland. Consequently, Hitler postponed his planned 26 August invasion of Poland

to 1 September. Britain and France responded by guaranteeing the sovereignty of Poland, so they declared war on Germany on 3 September.

— Adolf Hitler

in a public speech in Danzig at the end of September 1939

from the west. Within the first few days of the invasion, Germany began conducting massacres of Polish and Jewish civilians and POWs. These executions took place in over 30 towns and villages in the first month of German occupation alone. The Luftwaffe also took part by strafing fleeing civilian refugees on roads and carrying out an aerial bombing campaign. The Soviet Union assisted German air forces by allowing them to use signals broadcast by the Soviet radio station at Minsk allegedly "for urgent aeronautical experiments".

Stalin did not instantly interpret the protocol as permitting the Soviet Union to grab territory. Stalin was waiting to see whether the Germans would halt within the agreed area, and also the Soviet Union needed to secure the frontier in the Far East. On 17 September the Red Army

invaded eastern Poland

, violating the 1932 Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact, and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This was followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.

Polish troops already fighting much stronger German forces on its western side desperately tried to delay the capture of Warsaw. Consequently, Polish forces were not able to mount significant resistance against the Soviets. The Soviet Union marshaled 466,516 soldiers, 3,739 tanks, 380 armored cars, and approximately 1,200 fighters, 600 bombers, and 200 other aircraft against Poland. The Polish armed forces in the East consisted mostly of lightly armed border guard units of the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza (KOP), the 'border protection corps'. In the Northeast of Poland, only a few cities were defended and after a heavy but short struggle Polish forces withdrew to Lithuania

Polish troops already fighting much stronger German forces on its western side desperately tried to delay the capture of Warsaw. Consequently, Polish forces were not able to mount significant resistance against the Soviets. The Soviet Union marshaled 466,516 soldiers, 3,739 tanks, 380 armored cars, and approximately 1,200 fighters, 600 bombers, and 200 other aircraft against Poland. The Polish armed forces in the East consisted mostly of lightly armed border guard units of the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza (KOP), the 'border protection corps'. In the Northeast of Poland, only a few cities were defended and after a heavy but short struggle Polish forces withdrew to Lithuania

where they were interned. Some of the Polish forces which were fighting the Soviets in the far South of the nation withdrew to Romania

.

On 21 September, the Soviets and Germans signed a formal agreement coordinating military movements in Poland, including the "purging" of saboteurs. A joint German–Soviet parade was held in Lvov

and Brest-Litovsk, while the countries commanders met in the latter location. Stalin had decided in August that he was going to liquidate the Polish state, and a German–Soviet meeting in September addressed the future structure of the "Polish region". Soviet authorities immediately started a campaign of sovietization

of the newly acquired areas. The Soviets organized staged elections, the result of which was to become a legitimization of Soviet annexation of eastern Poland. Soviet authorities attempted to erase Polish history and culture, withdrew the Polish currency without exchanging roubles, collectivized

agriculture, and nationalized and redistributed private and state-owned Polish property. Soviet authorities regarded service for the pre-war Polish state as a "crime against revolution" and "counter-revolutionary activity", and subsequently started arresting large numbers of Polish citizens.

Eleven days after the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland, the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was modified by the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation,) allotting Germany a larger part of Poland and transferring Lithuania

Eleven days after the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland, the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was modified by the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation,) allotting Germany a larger part of Poland and transferring Lithuania

's territory (with the exception of left bank of river Scheschupe, the "Lithuanian Strip") from the envisioned German sphere to the Soviets. On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and German Reich issued a joint declaration in which they declared:

On 3 October, Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg

, German ambassador in Moscow, informed Joachim Ribbentrop that the Soviet government was willing to cede the city of Vilnius

and its environs. On 8 October 1939, a new Nazi-Soviet agreement was reached by an exchange of letters between Vyacheslav Molotov

and the German Ambassador.

The Baltic States

of Estonia

, Latvia

, and Lithuania

were given no choice but to sign a so-called Pact of defence and mutual assistance which permitted the Soviet Union to station troops in them.

After the Baltic states

After the Baltic states

were forced to accept treaties, Stalin turned his sights on Finland, confident that Finnish capitulation could be attained without great effort. The Soviets demanded territories on the Karelian Isthmus

, the islands of the Gulf of Finland

and a military base near the Finnish capital Helsinki

, which Finland rejected. The Soviets staged the shelling of Mainila

and used it as a pretext to withdraw from the non-aggression pact. The Red Army attacked

in November 1939. Simultaneously, Stalin set up a puppet government in the Finnish Democratic Republic

. The leader of the Leningrad Military District Andrei Zhdanov

commissioned a celebratory piece from Dmitri Shostakovich

, entitled "Suite on Finnish Themes

" to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army would be parading through Helsinki. After Finnish defenses surprisingly held out for over three months while inflicting stiff losses on Soviet forces, the Soviets settled for an interim peace. Finland ceded eastern areas of Karelia

(10% of Finnish territory), which resulted in approximately 422,000 Karelians (12% of Finland's population) losing their homes. Soviet official casualty counts in the war exceeded 200,000, while Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

later claimed the casualties may have been one million.

At around this time, after several Gestapo–NKVD Conferences, Soviet NKVD

officers also conducted lengthy interrogations of 300,000 Polish POWs in camps that were, in effect, a selection process to determine who would be killed. On March 5, 1940, in what would later be known as the Katyn massacre

, orders were signed to execute 25,700 Polish POWs, labeled "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries", kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine

and Belarus

.

, Soviet NKVD troops raided border posts in Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. State administrations were liquidated and replaced by Soviet cadres, in which 34,250 Latvians, 75,000 Lithuanians and almost 60,000 Estonians were deported or killed. Elections were held with single pro-Soviet candidates listed for many positions, with resulting peoples assemblies immediately requested admission into the USSR, which was granted by the Soviet Union. The USSR annexed the whole of Lithuania, including the Scheschupe area, which was to be given to Germany.

Finally, on 26 June, four days after France sued for an armistice with the Third Reich, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum demanding Bessarabia

and, unexpectedly, Northern Bukovina from Romania

. Two days later, the Romanians caved to the Soviet demands and the Soviets occupied the territory. The Hertza region

was initially not requested by the USSR but was later occupied by force after the Romanians agreed to the initial soviet demands.

. 50,000-200,000 Polish children were kidnapped to be Germanized.

Elimination of Polish elites and intelligentia was part of Generalplan Ost

Elimination of Polish elites and intelligentia was part of Generalplan Ost

. The Intelligenzaktion

, a plan to eliminate the Polish intelligentsia, Poland's 'leadership class', took place soon after the German invasion of Poland, lasting from fall of 1939 till spring of 1940. As the result of this operation in 10 regional actions were killed about 60,000 Polish nobles

, teachers, social workers, priests, judges and political activists. It was continued in May 1940 when Germany launched AB-Aktion, More than 16,000 members of the intelligentsia were murdered in Operation Tannenberg

alone.

Germany also planned to incorporate all land into the Third Reich. This effort resulted in the forced resettlement of 2 million Poles. Families were forced to travel in the severe winter of 1939–40, leaving behind almost all of their possessions without recompense. As part of Operation Tannenberg alone, 750,000 Polish peasants were forced to leave and their property was given to Germans. A further 330,000 were murdered. Germany eventually planned to move ethnic Poles to Siberia.

Although Germany used forced labourers in most occupied countries, Poles and other Eastern Europeans were viewed as inferior and, thus, better suited for such duties. Between 1 and 2.5 million Polish citizens were transported to the Reich for forced labour, against their will. All Polish males were required to perform forced labour.

While ethnic Poles were subject to selective persecution, all ethnic Jews were targeted by the Reich. In the winter of 1939–40, about 100,000 Jews were thus deported to Poland. They were initially gathered into massive urban ghettos, such as 380,000 held in the Warsaw Ghetto

, where large numbers died under the harsh conditions therein, including 43,000 in the Warsaw Ghetto alone. Poles and ethnic Jews were imprisoned in nearly every camp of the extensive concentration camp system

in German-occupied Poland and the Reich. In Auschwitz

, which began operating on 14 June 1940, 1.1 million people died.

of Romania.

On 30 August, Ribbentrop and Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano

issued the Second Vienna Award

giving Northern Transylvania to Hungary. On 7 September, Romania ceded Southern Dobruja

to Bulgaria (Axis

-sponsored Treaty of Craiova

). After various events in Romania, over the next few months, it increasingly took on the aspect of a German-occupied country.

The Soviet-occupied territories were converted into republics of the Soviet Union

. During the two years following the annexation, the Soviets arrested approximately 100,000 Polish citizens and deported

between 350,000 and 1,500,000, of whom between 250,000 and 1,000,000 died, mostly civilians. Forced re-settlements into Gulag

labour camps and exile settlements in remote areas of the Soviet Union

occurred. According to Norman Davies

, almost ½ of them were dead by July 1940. In Bessarabia, about 1,000,000 Romanians also died of famine or deportation.

On 10 January 1941, Germany and the Soviet Union signed an agreement settling several ongoing issues.

On 10 January 1941, Germany and the Soviet Union signed an agreement settling several ongoing issues.

Secret protocols in the new agreement modified the "Secret Additional Protocols" of the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, ceding the Lithuanian Strip to the Soviet Union in exchange for 7.5 million dollars (31.5 million Reichsmark

). The agreement formally set the border between Germany and the Soviet Union between the Igorka river and the Baltic Sea. It also extended trade regulation of the 1940 German–Soviet Commercial Agreement

until August 1, 1942, increased deliveries above the levels of year one of that agreement, settled trading rights in the Baltics and Bessarabia, calculated the compensation for German property interests in the Baltic States now occupied by the Soviets and other issues. It also covered the migration to Germany within two and a half months of ethnic Germans and German citizens in Soviet-held Baltic territories, and the migration to the Soviet Union of Baltic and "White Russian" "nationals" in German-held territories.

suspended all anti-Nazi and anti-fascist propaganda, explaining that the war in Europe was a matter of capitalist states attacking each other for imperialist purposes. When anti-German demonstrations erupted in Prague

, Czechoslovakia

, the Comintern ordered the Czech Communist Party

to employ all of its strength to paralyze "chauvinist elements." Moscow soon forced the Communist Parties of France

and Great Britain

to adopt an anti-war position. On 7 September, Stalin called Georgi Dimitrov

, and the latter sketched a new Comintern line on the war. The new line — which stated that the war was unjust and imperialist — was approved by the secretariat of the Communist International on 9 September. Thus, the various western Communist parties now had to oppose the war, and to vote against war credits. A number of French communists (including Maurice Thorez

, who fled to Moscow), deserted from the French Army

, owing to a 'revolutionary defeatist' attitude taken by Western Communist leaders. The Communist Party of Germany

featured similar attitudes. In Die Welt, a communist newspaper published in Stockholm the exiled communist leader Walter Ulbricht

opposed the allies (Britain representing “the most reactionary force in the world”) and argued: “The German government declared itself ready for friendly relations with the Soviet Union, whereas the English-French war bloc desires a war against the socialist Soviet Union. The Soviet people and the working people of Germany have an interest in preventing the English war plan.”

Despite a warming by the Comintern, German tensions were raised when the Soviets stated in September that they must enter Poland to "protect" their ethnic Ukrainian and Belorussian brethren therein from Germany, though Molotov later admitted to German officials that this excuse was necessary because the Soviets could find no other pretext for the Soviet invasion.

While active collaboration between Nazi Germany and Soviet Union caused great shock in western Europe and amongst communists opposed to Germany, on 1 October 1939, Winston Churchill

declared that the Russian armies acted for the safety of Russia against "the Nazi menace."

When a joint German-Soviet peace initiative was rejected by Britain and France on 28 September 1939, Soviet foreign policy became critical of the Allies and more pro-German in turn. During the fifth session of the Supreme Soviet on 31 October 1939 Molotov analysed the international situation thus giving the direction for Communist propaganda. According to Molotov Germany had a legitimate interest in regaining its position as a great power and the Allies had started an aggressive war in order to maintain the Versailles system.

Molotov declared in his report entitled "On the Foreign Policy of the Soviet Union" (31 October 1939) held on the fifth (extraordinary) session of the Supreme Soviet, that the Western "ruling circles" disguise their intentions with the pretext of defending democracy against Hitlerism, declaring "their aim in war with Germany

is nothing more, nothing less than extermination of Hitlerism. [...] There is absolutely no justification for this kind of war. The ideology of Hitlerism, just like any other ideological system, can be accepted or rejected, this is a matter of political views. But everyone grasps, that an ideology can not be exterminated by force, must not be finished off with a war."

, that was over four times larger than the one the two countries had signed in August of 1939. The trade pact helped Germany to surmount a British blockade of Germany. In the first year, Germany received one million tons of cereals, half a million tons of wheat, 900,000 tons of oil, 100,000 tons of cotton, 500,000 tons of phosphates and considerable amounts of other vital raw materials, along with the transit of one million tons of soybeans from Manchuria

. These and other supplies were being transported through Soviet and occupied Polish territories. The Soviets were to receive a naval cruiser, the plans to the battleship Bismarck

, heavy naval guns, other naval gear and thirty of Germany's latest warplanes, including the Me-109 and Me-110 fighters and Ju-88 bomber. The Soviets would also receive oil and electric equipment, locomotives, turbines, generators, diesel engines, ships, machine tools and samples of Germany artillery, tanks, explosives, chemical-warfare equipment and other items.

The Soviets also helped Germany to avoid British naval blockades by providing a submarine base, Basis Nord

, in the northern Soviet Union near Murmansk

. This also provided a refueling and maintenance location, and a takeoff point for raids and attacks on shipping. In addition, the Soviets provided Germany with access to the Northern Sea Route

for both cargo ships and raiders (though only the commerce raider used the route before the German invasion), which forced Britain to protect sea lanes in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

In August 1940, the Soviet Union briefly suspended its deliveries under their commercial agreement

after their relations were strained following disagreement over policy in Romania, the Soviet war with Finland

, Germany falling behind in its deliveries of goods under the pact and with Stalin worried that Hitler's war with the West might end quickly after France signed an armistice

. The suspension created significant resource problems for Germany. By the end of August, relations improved again as the countries had redrawn the Hungarian and Romanian borders

, settled some Bulgarian claims and Stalin was again convinced that Germany would face a long war in the west with Britain's improvement in its air battle with Germany

and the execution of an agreement between the United States and Britain regarding destroyers and bases

. However, in late August, Germany arranged its own occupation of Romania, targeting oil fields. The move raised tensions with the Soviets, who responded that Germany was supposed to have consulted with the Soviet Union under Article III of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

After Germany entered a Tripartite Pact

After Germany entered a Tripartite Pact

with Japan and Italy, Ribbentrop wrote to Stalin, inviting Molotov to Berlin for negotiations aimed to create a 'continental bloc' of Germany, Italy, Japan and the USSR that would oppose Britain and the USA. Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to negotiate the terms for the Soviet Union to join the Axis and potentially enjoy the spoils of the pact. After negotiations during November 1940 on where to extend the USSR's sphere of influence, Hitler broke off talks and continued planning for the eventual attempts to invade the Soviet Union.

Despite publication of the recovered copy in western media, for decades, it was the official policy of the Soviet Union to deny the existence of the secret protocol. The secret protocol's existence was officially denied until 1989. Vyacheslav Molotov

, one of the signatories, went to his grave categorically rejecting its existence.

On 23 August 1986, tens of thousands of demonstrators in 21 western cities including New York, London, Stockholm, Toronto, Seattle, and Perth participated in Black Ribbon Day Rallies to draw attention to the secret protocols.

, which included the claim that, during the Pact's operation, Stalin rejected Hitler's claim to share in a division of the world, without mentioning the Soviet offer to join the Axis

. That version persisted, without exception, in historical studies, official accounts, memoirs and textbooks published in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution

.

The book also claimed that the Munich agreement

was a "secret agreement" between Germany and "the west" and a "highly important phase in their policy aimed at goading the Hitlerite aggressors against the Soviet Union."

demonstrations of 23 August 1989, where two million people created a human chain set on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Pact that this policy changed. At the behest of Mikhail Gorbachev

, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev

headed a commission investigating the existence of such a protocol. In December 1989, the commission concluded that the protocol had existed and revealed its findings to the Soviet Congress of People's Deputies. As a result, the first democratically elected Congress of Soviets

passed the declaration confirming the existence of the secret protocols, condemning and denouncing them.

Both successor-states of the pact parties have declared the secret protocols to be invalid from the moment they were signed. The Federal Republic of Germany declared this on September 1, 1989 and the Soviet Union on December 24, 1989, following an examination of the microfilmed copy of the German originals.

The Soviet copy of the original document was declassified in 1992 and published in a scientific journal in early 1993.

In August 2009, in an article written for the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza

, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin

condemned the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact as "immoral."

be included in the Soviet sphere of influence.

Regarding the timing of German rapprochement, many historians agree that the dismissal of Litvinov, whose Jewish ethnicity was viewed unfavorably by Nazi Germany

, removed an obstacle to negotiations with Germany. Stalin immediately directed Molotov to "purge the ministry of Jews." Given Litvinov's prior attempts to create an anti-fascist coalition, association with the doctrine of collective security

with France and Britain, and pro-Western orientation by the standards of the Kremlin, his dismissal indicated the existence of a Soviet option of rapprochement with Germany. Likewise, Molotov's appointment served as a signal to Germany that the USSR was open to offers. The dismissal also signaled to France and Britain the existence of a potential negotiation option with Germany. One British official wrote that Litvinov's disappearance also meant the loss of an admirable technician or shock-absorber, while Molotov's "modus operandi" was "more truly Bolshevik than diplomatic or cosmopolitan." Carr argued that the Soviet Union's replacement of Foreign Minister Litvinov with Molotov on May 3, 1939 indicated not an irrevocable shift towards alignment with Germany, but rather was Stalin’s way of engaging in hard bargaining with the British and the French by appointing a proverbial hard man, namely Molotov, to the Foreign Commissariat. Historian Albert Resis

stated that the Litvinov dismissal gave the Soviets freedom to pursue faster-paced German negotiations, but that they did not abandon British–French talks. Derek Watson argued that Molotov could get the best deal with Britain and France because he was not encumbered with the baggage of collective security and could negotiate with Germany. Geoffrey Roberts argued that Litvinov's dismissal helped the Soviets with British–French talks, because Litvinov doubted or maybe even opposed such discussions.

After the war, defenders of the Soviet position argued that it was necessary to enter into a non-aggression pact with Germany to buy time, since the Soviet Union was not in a position to fight a war in 1939, and needed at least three years to prepare. Edward Hallett Carr, a frequent defender of Soviet policy, stated: "In return for 'non-intervention' Stalin secured a breathing space of immunity from German attack." According to Carr, the "bastion" created by means of the Pact, "was and could only be, a line of defense against potential German attack." According to Carr, an important advantage was that "if Soviet Russia had eventually to fight Hitler, the Western Powers would already be involved." However, during the last decades, this view has been disputed. Historian Werner Maser stated that "the claim that the Soviet Union was at the time threatened by Hitler, as Stalin supposed,...is a legend, to whose creators Stalin himself belonged." (Maser 1994: 64). In Maser's view (1994: 42), "neither Germany nor Japan were in a situation [of] invading the USSR even with the least perspective [sic] of success," and this could not have been unknown to Stalin. Carr further stated that, for a long time, the primary motive of Stalin's sudden change of course was assumed to be the fear of German aggressive intentions.

Some critics of Stalin's policy, such as the popular writer Viktor Suvorov

, claim that Stalin's primary motive for signing the Soviet–German non-aggression treaty was his calculation that such a pact could result in a conflict between the capitalist countries of Western Europe. This idea is supported by Albert L. Weeks. Claims by Suvorov that Stalin planned to invade Germany in 1941 are debated by historians with, for example, David Glantz

opposing such claims, while Mikhail Meltyukhov supports them. The authors of The Black Book of Communism

consider the pact a crime against peace

and a "conspiracy to conduct war of aggression

."

Soviet sources have claimed that soon after the pact was signed, both the UK and US showed understanding that the buffer zone was necessary to keep Hitler from advancing for some time, accepting the ostensible strategic reasoning; however, soon after World War II ended, those countries changed their view. Many Polish newspapers published numerous articles claiming that Russia must apologize to Poland for the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

Two weeks after Soviet armies had entered the Baltic states, Berlin requested Finland to permit the transit of German troops, followed five weeks thereafter by Hitler's issuance of a secret directive "to take up the Russian problem, to think about war preparations," a war whose objective would include establishment of a Baltic confederation. There is an opinion that the ensuing Axis invasion of the USSR

was prompted by Soviet actions in the Baltics and the war against Finland

.

has proclaimed 23 August, the anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, as a European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism

, to be commemorated with dignity and impartiality.

In connection with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, an Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe parliamentary resolution condemned both communism

and fascism

for starting World War II

and called for a day of remembrance for victims of both Stalinism and Nazism on 23 August. In response to the resolution, the Russian lawmakers threatened the OSCE with "harsh consequences".

During the re-ignition of Cold War tensions in 1982, the U.S. Congress during Reagan Administration

established the Baltic Freedom Day

to be remembered every June 14 in the United States.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop was Foreign Minister of Germany from 1938 until 1945. He was later hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials.-Early life:...

, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

in the late hours of 23 August 1939. It was a non-aggression pact

Non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact is an international treaty between two or more states/countries agreeing to avoid war or armed conflict between them and resolve their disputes through peaceful negotiations...

under which the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

each pledged to remain neutral

Neutrality (international relations)

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

in the event that either nation were attacked by a third party. It remained in effect until 22 June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

.

In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol dividing Northern

Northern Europe

Northern Europe is the northern part or region of Europe. Northern Europe typically refers to the seven countries in the northern part of the European subcontinent which includes Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Finland and Sweden...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

into German and Soviet spheres of influence, anticipating potential "territorial and political rearrangements" of these countries. Thereafter, Germany and the Soviet Union invaded

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

, on September 1 and 17 respectively, their respective sides of Poland

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

, dividing the country between them. Part of eastern Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

was annexed by the Soviet Union after the Winter War

Winter War

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty...

. This was followed by Soviet annexation

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

s of Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

, Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

, Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

, Northern Bukovina

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

and the Hertza region

Hertza region

Hertza region is the territory of an administrative district of Hertsa in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, on the Romanian border...

.

Names

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact is commonly referred to under a number of names in addition to the official one and the one bearing the names of the foreign ministers. It is also known as the Nazi–Soviet Pact, Hitler–Stalin Pact, German–Soviet Non-aggression Pact and sometimes the Nazi–Soviet Alliance.Background

The outcome of the First World WarWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

was disastrous for both the German Reich

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , commonly referred to as Soviet Russia, Bolshevik Russia, or simply Russia, was the largest, most populous and economically developed republic in the former Soviet Union....

. During the war, the Bolsheviks struggled for survival, and Lenin had no option except to recognize the independence of Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

, Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

, Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

and Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

. Moreover, facing a German military advance, Lenin and Trotsky were forced to enter into the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

, which ceded some western Russian territory to the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. After Germany's collapse, British

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

, French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese troops intervened in the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

.

On 16 April 1922, Germany and Soviet Russia

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

entered the Treaty of Rapallo

Treaty of Rapallo, 1922

The Treaty of Rapallo was an agreement signed at the Hotel Imperiale in the Italian town of Rapallo on 16 April, 1922 between Germany and Soviet Russia under which each renounced all territorial and financial claims against the other following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and World War I.The two...

, pursuant to which they renounced territorial and financial claims against each other. The parties further pledged neutrality in the event of an attack against one another with the 1926 Treaty of Berlin. While trade between the two countries fell sharply after World War I, trade agreements signed in the mid-1920s helped to increase trade to 433 million Reichsmarks per year by 1927.

At the beginning of the 1930s, the Nazi Party's rise to power increased tensions between Germany, the Soviet Union and other countries with ethnic Slavs, which were considered "Untermensch

Untermensch

Untermensch is a term that became infamous when the Nazi racial ideology used it to describe "inferior people", especially "the masses from the East," that is Jews, Gypsies, Poles along with other Slavic people like the Russians, Serbs, Belarussians and Ukrainians...

en" according to Nazi racial ideology

Racial policy of Nazi Germany

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented by Nazi Germany, asserting the superiority of the "Aryan race", and based on a specific racist doctrine which claimed scientific legitimacy...

. Moreover, the anti-Semitic Nazis associated ethnic Jews with both communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and financial capitalism

Financial capitalism

Financial capitalism is a form of capitalism where the intermediation of savings to investment becomes a dominant function in the economy, with implications for the political process and social evolution...

, both of which they opposed

Third Position

Third Position is a revolutionary nationalist political ideology that emphasizes its opposition to both communism and capitalism. Advocates of Third Position politics typically present themselves as "beyond left and right", instead claiming to syncretize radical ideas from both ends of the...

. Consequently, Nazi theory held that Slavs in the Soviet Union were being ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik

Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, Judeo-Bolshevism, and known as Żydokomuna in Poland, is an antisemitic stereotype based on the claim that Jews have been the driving force behind or are disproportionately involved in the modern Communist movement, or sometimes more specifically Russian Bolshevism.The expression...

" masters. In 1934, Hitler himself had spoken of an inescapable battle against both Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism was a movement in the mid-19th century aimed at unity of all the Slavic peoples. The main focus was in the Balkans where the South Slavs had been ruled for centuries by other empires, Byzantine Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice...

and Neo-Slavism, the victory in which would lead to "permanent mastery of the world", though he stated that they would "walk part of the road with the Russians, if that will help us." The resulting manifestation of German anti-Bolshevism and an increase in Soviet foreign debts caused German–Soviet trade to dramatically decline. Imports of Soviet goods to Germany fell to 223 million Reichsmarks in 1934 as the more isolationist Stalinist regime asserted power and the abandonment of post–World War I Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

military controls decreased Germany's reliance on Soviet imports.

In 1936, Germany and Fascist Italy

Italian Fascism

Italian Fascism also known as Fascism with a capital "F" refers to the original fascist ideology in Italy. This ideology is associated with the National Fascist Party which under Benito Mussolini ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, the Republican Fascist Party which ruled the Italian...

supported Spanish Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, while the Soviets supported the partially socialist-led Second Spanish Republic

Second Spanish Republic

The Second Spanish Republic was the government of Spain between April 14 1931, and its destruction by a military rebellion, led by General Francisco Franco....

under the leadership of president Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz was a Spanish politician. He was the first Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic , and later served again as Prime Minister , and then as the second and last President of the Republic . The Spanish Civil War broke out while he was President...

. Thus, in a sense, the Spanish Civil War became also the scene of a proxy war

Proxy war

A proxy war or proxy warfare is a war that results when opposing powers use third parties as substitutes for fighting each other directly. While powers have sometimes used governments as proxies, violent non-state actors, mercenaries, or other third parties are more often employed...

between Germany and the USSR. In 1936, Germany and Japan entered the Anti-Comintern Pact

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact was an Anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on November 25, 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ....

, and were joined a year later by Italy

Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

.

Hitler's fierce anti-Soviet rhetoric was one of the reasons why the UK and France decided that Soviet participation in the 1938 Munich Conference regarding Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

would be both dangerous and useless. The Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

that followed marked a partial German annexation

German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

of Czechoslovakia in late 1938 followed by its complete dissolution in March 1939, which is seen as part of an appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

of Germany conducted by Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

's and Daladier's cabinets. This policy immediately raised the question of whether the Soviet Union could avoid being next on Hitler's list. The Soviet leadership believed that the West may want to encourage German aggression in the East and that France and Britain might stay neutral in a war initiated by Germany, hoping that the warring states would wear each other out and put an end to both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

For Germany, because an autarkic

Autarky

Autarky is the quality of being self-sufficient. Usually the term is applied to political states or their economic policies. Autarky exists whenever an entity can survive or continue its activities without external assistance. Autarky is not necessarily economic. For example, a military autarky...

economic approach or an alliance with Britain were impossible, closer relations with the Soviet Union to obtain raw materials became necessary, if not just for economic reasons alone. Moreover, an expected British blockade in the event of war would create massive shortages for Germany in a number of key raw materials. After the Munich agreement, the resulting increase in German military supply needs and Soviet demands for military machinery, talks between the two countries occurred from late 1938 to March 1939. The third Soviet Five Year Plan required massive new infusions of technology and industrial equipment.

On 31 March 1939, in response to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

's defiance of the Munich Agreement and occupation of Czechoslovakia, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

pledged the support of itself and France

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

to guarantee the independence of Poland, Belgium, Romania, Greece, and Turkey. On 6 April Poland and the UK agreed to formalize the guarantee as a military alliance, pending negotiations. On 28 April, Hitler denounced the 1934 German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact and the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement

Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of June 18, 1935 was a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and German Reich regulating the size of the Kriegsmarine in relation to the Royal Navy. The A.G.N.A fixed a ratio whereby the total tonnage of the Kriegsmarine was to be 35% of the total tonnage...

.

Starting in mid-March 1939, the Soviet Union, Britain and France traded a flurry of suggestions and counterplans regarding a potential political and military agreement. Although informal consultations commenced in April, the main negotiations began only in May. At the same time, throughout the early 1939,Germany and the Soviet Union had discussed a possibility of an economic deal involving industrial equipment and armament for the USSR in exchange for raw materials needed for German war production. German war planners had estimated massive raw materials shortfalls if Germany entered a war without Soviet supply. For months, Germany had secretly hinted to Soviet diplomats that it could offer better terms for a political agreement than Britain and France.

The Soviet Union feared Western powers and the possibility of "capitalist encirclements", had little faith either that war could be avoided, or faith in the Polish army, and wanted nothing less than an ironclad military alliance that would provide a guaranteed support for a two-pronged attack on Germany. Britain and France believed that war could still be avoided, and that the Soviet Union, weakened by the Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

, could not be a main military participant, a point that many military sources were at variance with, especially after the sound thrashing administered to the Japanese Kwantung army on the Manchurian frontier. France was more anxious to find an agreement with the USSR than was Britain; as a continental power, it was more willing to make concessions, more fearful of the dangers of an agreement between the USSR and Germany. These contrasting attitudes partly explain why the USSR has often been charged with playing a double game in 1939: carrying on open negotiations for an alliance with Britain and France while secretly considering propositions from Germany.

By the end of May drafts were formally presented. In mid-June the main Tripartite negotiations started. The discussion was focused on potential guarantees to central and east European countries should a German aggression arise. The USSR proposed to consider that a political turn towards Germany by the Baltic states

Baltic states

The term Baltic states refers to the Baltic territories which gained independence from the Russian Empire in the wake of World War I: primarily the contiguous trio of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania ; Finland also fell within the scope of the term after initially gaining independence in the 1920s.The...

would constitute an "indirect aggression" towards the Soviet Union. Britain opposed such proposals, because they feared the Soviets' proposed language could justify a Soviet intervention in Finland and the Baltic states, or push those countries to seek closer relations with Germany. The discussion about a definition of "indirect aggression" became one of the sticking points between the parties, and by mid-July the tripartite political negotiations effectively stalled, while the parties agreed to start negotiations on a military agreement, which the Soviets insisted must be entered into simultaneously with any political agreement.

Beginning of Soviet–German secret talks

From April–July, Soviet and German officials made statements regarding the potential for the beginning of political negotiations, while no actual negotiations took place during that time period. The ensuing discussion of a potential political deal between Germany and the Soviet Union had to be channeled into the framework of economic negotiations between the two countries, because close military and diplomatic connections, as was the case before mid-1930s, had afterward been largely severed. In May, Stalin replaced his Foreign Minister Maxim LitvinovMaxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet diplomat.- Early life and first exile :...

, who was regarded as pro-western and who was also Jewish, with Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, allowing the Soviet Union more latitude in discussions with more parties, not only with Britain and France.

In late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German officials agreed on most of the details for a planned economic agreement, and specifically addressed a potential political agreement, which the Soviets stated could only come after an economic agreement.

August negotiations

In early August, Germany and the Soviet Union worked out the last details of their economic deal, and started to discuss a political alliance. They explained to each other the reasons for their foreign policy hostility in the 1930s, finding common ground in the anti-capitalismAnti-capitalism

Anti-capitalism describes a wide variety of movements, ideas, and attitudes which oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists, in the strict sense of the word, are those who wish to completely replace capitalism with another system....

of both countries.

At the same time, Tripartite Soviet–British–French negotiators scheduled talks on military matters to occur in Moscow in August 1939, aiming to define the specifics of what should be the reaction of the Soviet Union, France and Britain, if they were to sign any agreement, in case a German attack occur. The tripartite military talks started in mid-August, hit a sticking point regarding passage of Soviet troops through Poland if Germans attacked, and the parties waited as British and French officials overseas pressured Polish officials to agree to such terms. Polish officials refused to allow Soviet troops on to Polish territory if Germans attacked; as Polish foreign minister Józef Beck

Józef Beck

' was a Polish statesman, diplomat, military officer, and close associate of Józef Piłsudski...

pointed out, they feared that once the Red Army entered their territories, it might never leave. While Britain and France refused to allow Soviet Union to impinge on the sovereignty of its neighbors, Germany possessed no such reservations.

On August 19, the 1939 German–Soviet Commercial Agreement was finally signed. On 21 August the Soviets suspended Tripartite military talks, citing other reasons. That same day, Stalin received assurance that Germany would approve secret protocols to the proposed non-aggression pact that would place half of Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

(border along the Vistula river), Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

, Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

, Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, and Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

in the Soviets' sphere of influence. That night, Stalin replied that the Soviets were willing to sign the pact, and that he would receive Ribbentrop on 23 August.

The secret protocol

Izvestia

Izvestia is a long-running high-circulation daily newspaper in Russia. The word "izvestiya" in Russian means "delivered messages", derived from the verb izveshchat . In the context of newspapers it is usually translated as "news" or "reports".-Origin:The newspaper began as the News of the...

, August 21, 1939.

Non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact is an international treaty between two or more states/countries agreeing to avoid war or armed conflict between them and resolve their disputes through peaceful negotiations...

was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other."

Northern Europe

Northern Europe is the northern part or region of Europe. Northern Europe typically refers to the seven countries in the northern part of the European subcontinent which includes Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Finland and Sweden...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence". In the North, Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

and Latvia

Latvia