German occupation of Czechoslovakia

Encyclopedia

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

of Czechoslovakia's

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by ethnic German

Ethnic German

Ethnic Germans historically also ), also collectively referred to as the German diaspora, refers to people who are of German ethnicity. Many are not born in Europe or in the modern-day state of Germany or hold German citizenship...

populations living in those regions. There also existed new and extensive Czechoslovak border fortifications

Czechoslovak border fortifications

The Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

in the same area.

Following the Anschluss

Anschluss

The Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, in March 1938, the conquest of Czechoslovakia became Hitler's next ambition. The incorporation of Sudetenland into Nazi Germany left the rest of Czechoslovakia weak and it became powerless to resist subsequent occupation. On 16 March 1939, the German Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

moved into the remainder of Czechoslovakia and, from Prague Castle

Prague Castle

Prague Castle is a castle in Prague where the Kings of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors and presidents of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic have had their offices. The Czech Crown Jewels are kept here...

, Hitler proclaimed Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

. The occupation ended with the surrender of Germany following World War II.

Demands for Sudeten autonomy

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

offered the Sudeten German Party (SdP) as the agent for Hitler's campaign. Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on 28 March 1938, where he was instructed to raise demands unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government led by president Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

. On 24 April, the SdP issued the Carlsbad Decrees

Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Bohemia...

, demanding autonomy

Autonomy

Autonomy is a concept found in moral, political and bioethical philosophy. Within these contexts, it is the capacity of a rational individual to make an informed, un-coerced decision...

for the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

and the freedom to profess Nazi ideology

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

. If Henlein's demands were granted, the Sudetenland would then be able to align itself with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

.

The Munich Agreement

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

alone and took its lead from the British government and its Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

. Chamberlain believed that Sudeten German grievances were justified and that Hitler's intentions were limited. Both Britain and France, therefore, advised Czechoslovakia to concede to the Nazi demands. Beneš resisted, and on 20 May a partial mobilization

Mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and making both troops and supplies ready for war. The word mobilization was first used, in a military context, in order to describe the preparation of the Prussian army during the 1850s and 1860s. Mobilization theories and techniques have continuously changed...

was under way in response to possible German invasion. Ten days later, Hitler signed a secret directive for war against Czechoslovakia to begin no later than 1 October.

In the meantime, the British government demanded that Beneš request a mediator. Not wishing to sever his government's ties with Western Europe, Beneš reluctantly accepted. The British appointed Lord Runciman

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford PC was a prominent Liberal, later National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom from the 1900s until the 1930s.-Background:...

and instructed him to persuade Beneš to agree to a plan acceptable to the Sudeten Germans. On 2 September, Beneš submitted the Fourth Plan, granting nearly all the demands of the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

. Intent on obstructing conciliation, however, the SdP held demonstrations that provoked police action in Ostrava

Ostrava

Ostrava is the third largest city in the Czech Republic and the second largest urban agglomeration after Prague. Located close to the Polish border, it is also the administrative center of the Moravian-Silesian Region and of the Municipality with Extended Competence. Ostrava was candidate for the...

on 7 September. The Sudeten Germans broke off negotiations on 13 September, after which violence and disruption ensued. As Czechoslovak troops attempted to restore order, Henlein flew to Germany, and on 15 September issued a proclamation demanding the takeover of the Sudetenland by Germany.

On the same day, Hitler met with Chamberlain and demanded the swift takeover of the Sudetenland by the Third Reich under threat of war. The Czechs, Hitler claimed, were slaughtering the Sudeten Germans. Chamberlain referred the demand to the British and French governments; both accepted. The Czechoslovak government resisted, arguing that Hitler's proposal would ruin the nation's economy and lead ultimately to German control of all of Czechoslovakia. The United Kingdom and France issued an ultimatum, making a French commitment to Czechoslovakia contingent upon acceptance. On 21 September, Czechoslovakia capitulated. The next day, however, Hitler added new demands, insisting that the claims of ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary also be satisfied.

The Czechoslovak capitulation precipitated an outburst of national indignation. In demonstrations and rallies, Czechs and Slovaks called for a strong military government to defend the integrity of the state. A new cabinet—under General Jan Syrový

Jan Syrový

Jan Syrový was a Czechoslovak Army four star general and the prime minister during the Munich Crisis.-Early life and military career:...

—was installed, and on 23 September a decree of general mobilization was issued. The Czechoslovak army—modern and possessing an excellent system of frontier fortifications

Czechoslovak border fortifications

The Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

—was prepared to fight. The Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance. Beneš, however, refused to go to war without the support of the Western powers.

On 28 September, Chamberlain appealed to Hitler for a conference. Hitler met the next day, at Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, with the chiefs of governments of France, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

and Britain. The Czech government was neither invited nor consulted. On 29 September, the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

was signed by Germany, Italy, France, and Britain. The Czechoslovak government capitulated on 30 September and agreed to abide by the agreement. The Munich Agreement stipulated that Czechoslovakia must cede Sudeten territory to Germany. German occupation of the Sudetenland would be completed by 10 October. An international commission representing Germany, Britain, France, Italy, and Czechoslovakia would supervise a plebiscite to determine the final frontier. Britain and France promised to join in an international guarantee of the new frontiers against unprovoked aggression. Germany and Italy, however, would not join in the guarantee until the Polish and Hungarian minority problems were settled.

On 5 October, Beneš resigned as President of Czechoslovakia, realising that the fall of Czechoslovakia was fait accompli. Following the outbreak of World War II, he would form a Czechoslovak government-in-exile

Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile was an informal title conferred upon the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee, initially by British diplomatic recognition. The name came to be used by other World War II Allies as they subsequently recognized it...

in London.

The first Vienna Award

In early November 1938, under the first Vienna AwardVienna Awards

The Vienna Awards are two arbitral awards by which arbiters of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy sought to enforce peacefully the claims of Hungary on territory it had lost in 1920 when it signed the Treaty of Trianon...

, which was a result of the Munich agreement, Czechoslovakia (and later Slovakia)—after it had failed to reach a compromise with Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

and Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

—was forced by Germany and Italy to cede southern Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

(one third of Slovak territory) to Hungary, while Poland invaded Zaolzie territory shortly after.

As a result, Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

and Silesia

Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia is an unofficial name of one of the three Czech lands and a section of the Silesian historical region. It is located in the north-east of the Czech Republic, predominantly in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with a section in the northern Olomouc Region...

lost about 38% of their combined area to Germany, with some 3.2 million German and 750,000 Czech

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

inhabitants. Hungary, in turn, received 11882 km² (4,587.7 sq mi) in southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia

Ruthenia

Ruthenia is the Latin word used onwards from the 13th century, describing lands of the Ancient Rus in European manuscripts. Its geographic and culturo-ethnic name at that time was applied to the parts of Eastern Europe. Essentially, the word is a false Latin rendering of the ancient place name Rus...

; according to a 1941 census, about 86.5% of the population in this territory was Hungarian. Meanwhile Poland annexed the town of Český Těšín

Ceský Tešín

Český Těšín is a town in the Karviná District, Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. The town is commonly known in the region as just Těšín . It lies on the west bank of the Olza River, in the heart of the historical region of Cieszyn Silesia...

with the surrounding area

Zaolzie

Zaolzie is the Polish name for an area now in the Czech Republic which was disputed between interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia. The name means "lands beyond the Olza River"; it is also called Śląsk zaolziański, meaning "trans-Olza Silesia". Equivalent terms in other languages include Zaolší in...

(some 906 km² (349.8 sq mi), some 250,000 inhabitants, Poles made about 36% of population) and two minor border areas in northern Slovakia, more precisely in the regions Spiš

Spiš

Spiš is a region in north-eastern Slovakia, with a very small area in south-eastern Poland. Spiš is an informal designation of the territory , but it is also the name of one the 21 official tourism regions of Slovakia...

and Orava

Orava (county)

Árva is the Hungarian name of a historic administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is presently in northern Slovakia and southern Poland...

. (226 km² (87.3 sq mi), 4,280 inhabitants, only 0.3% Poles).

Soon after Munich, 115,000 Czechs and 30,000 Germans fled to the remaining rump of Czechoslovakia. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugee

Refugee

A refugee is a person who outside her country of origin or habitual residence because she has suffered persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because she is a member of a persecuted 'social group'. Such a person may be referred to as an 'asylum seeker' until...

s on 1 March 1939 stood at almost 150,000.

On 4 December 1938, there were elections in Reichsgau Sudetenland, in which 97.32% of the adult population voted for NSDAP. About 500,000 Sudeten Germans joined the Nazi Party which was 17.34% of the German population in Sudetenland (the average NSDAP participation in Nazi Germany was 7.85%). This means the Sudetenland was the most "pro-Nazi" region in the Third Reich. Because of their knowledge of the Czech language, many Sudeten Germans were employed in the administration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as well as in Nazi organizations (Gestapo, etc.). The most notable was Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in Czechoslovakia prior to and during World War II and an SS-Obergruppenführer...

: the SS and Police general and Secretary of State in the Protectorate.

The Second Republic (October 1938 to March 1939)

The greatly weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs. The executive committee of the Slovak People's Party met at Žilina on 5 October 1938, and with the acquiescence of all Slovak parties except the Social Democrats formed an autonomous Slovak government under Jozef TisoJozef Tiso

Jozef Tiso was a Slovak Roman Catholic priest, politician of the Slovak People's Party, and Nazi collaborator. Between 1939 and 1945, Tiso was the head of the Slovak State, a satellite state of Nazi Germany...

. Similarly, the two major factions in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the Russophiles

Ukrainian Russophiles

The focus of this article is part of a general political movement in Western Ukraine of the nineteenth and early 20th century. The movement contained several competing branches: Moscowphiles, Ukrainophiles, Rusynphiles, and others....

and Ukrainophiles, agreed on the establishment of an autonomous government, which was constituted on 8 October. Reflecting the spread of modern Ukrainian national consciousness, the pro-Ukrainian faction, led by Avhustyn Voloshyn

Avhustyn Voloshyn

Avgustyn Ivanovych Voloshyn was a Ukrainian politician, teacher, and essayist. He was president of the independent Carpatho-Ukraine, which existed for one day on March 15, 1939....

, gained control of the local government and Subcarpathian Ruthenia was renamed Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine was an autonomous region within Czechoslovakia from late 1938 to March 15, 1939. It declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939, but was occupied by Hungary between March 15 and March 18, 1939, remaining under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in...

.

A last-ditch attempt to save Czecho-Slovakia from total ruin was made by the British and French governments, who on 27 January 1939, concluded an agreement of financial assistance with the Czech government. In this agreement, the British and French governments undertook to lend the Czech government ₤8,000,000 and make a gift of ₤4,000,000. Part of the funds was allocated to help resettle Czechs who had fled from territories lost to Czechoslovakia in the Munich Agreement or the Vienna Arbitration Award.

Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha was a Czech lawyer, the third President of Czecho-Slovakia from 1938 to 1939. From March 1939, he presided under the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.-Judicial career:...

—succeeding Beneš—was elected president of the federated Second Republic

Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic refers to the second Czechoslovak state that existed from October 1, 1938 to March 14, 1939, thus existing for only 167 days...

, renamed Czecho-Slovakia and consisting of three parts: Bohemia and Moravia, Slovakia, and Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine was an autonomous region within Czechoslovakia from late 1938 to March 15, 1939. It declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939, but was occupied by Hungary between March 15 and March 18, 1939, remaining under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in...

. Lacking its natural frontier and having lost its costly system of border fortification, the new state was militarily indefensible. In January 1939, negotiations between Germany and Poland broke down. Hitler—intent on war against Poland—needed to eliminate Czechoslovakia first. He scheduled a German invasion of Bohemia and Moravia for the morning of 15 March. In the interim, he negotiated with the Slovak People's Party

Slovak People's Party

The Slovak People's Party was a Slovak right-wing party and was described as a fascist and...

and with Hungary to prepare the dismemberment of the republic before the invasion. On 13 March, he invited Tiso to Berlin and on 14 March, the Slovak Diet convened and unanimously declared Slovak independence. Carpatho-Ukraine also declared independence but Hungarian troops occupied it on 15 March and eastern Slovakia on 23 March.

Hitler summoned President Hácha to Berlin and during the early hours of 15 March, informed Hácha of the imminent German invasion. Threatening a Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

attack on Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

, Hitler persuaded Hácha to order the capitulation of the Czechoslovak army. Hácha suffered a heart attack during the meeting, and had to be kept awake by medical staff, eventually giving in and accepting Hitler's surrender terms. Then on the morning of 15 March, German troops entered Bohemia and Moravia, meeting practically no resistance (the only instance of organized resistance took place in Místek

Frýdek-Místek

Frýdek-Místek is a city in Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It is the administrative center of Frýdek-Místek District. It comprises two formerly independent towns, Frýdek and Místek, divided by the Ostravice River...

where an infantry company commanded by Karel Pavlík

Karel Pavlík

Karel Pavlík was a Czechoslovak Army captain and decorated hero of Czechoslovakia....

fought invading German troops). The Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine was an autonomous region within Czechoslovakia from late 1938 to March 15, 1939. It declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939, but was occupied by Hungary between March 15 and March 18, 1939, remaining under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in...

encountered resistance but the Hungarian army quickly crushed it. On 16 March, Hitler went to Czechoslovakia and from Prague Castle

Prague Castle

Prague Castle is a castle in Prague where the Kings of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors and presidents of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic have had their offices. The Czech Crown Jewels are kept here...

proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate (Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

).

Thus, independent Czechoslovakia collapsed in the wake of foreign aggression and internal tensions. Subsequently, interwar Czechoslovakia has been idealized by its proponents as the only bastion of democracy surrounded by authoritarian and fascist regimes. It has also been condemned by its detractors as an artificial and unworkable creation of intellectuals supported by the great powers. Both views have some validity. Interwar Czechoslovakia comprised lands and peoples that were far from being integrated into a modern nation-state. Moreover, the dominant Czechs—who had suffered political discrimination under the Habsburgs—were not able to cope with the demands of other nationalities; however, it should be acknowledged that some of the minority demands served as mere pretexts to justify intervention by Nazi Germany. Considering that Czechoslovakia was able to maintain a viable economy and a democratic political system under such circumstances was indeed a remarkable achievement during the inter-war period.

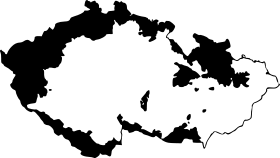

Division of Czechoslovakia

During World War II, Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. Its territory was divided into the Protectorate of Bohemia and MoraviaProtectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

and the newly-declared Slovak Republic

Slovak Republic (1939-1945)

The Slovak Republic , also known as the First Slovak Republic or the Slovak State , was a fascist state which existed from 14 March 1939 to 8 May 1945 as a puppet state of Nazi Germany. It existed on roughly the same territory as present-day Slovakia...

, while the considerable part of Czechoslovakia was directly joined to the Third Reich. Some parts (e.g. Zaolzie

Zaolzie

Zaolzie is the Polish name for an area now in the Czech Republic which was disputed between interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia. The name means "lands beyond the Olza River"; it is also called Śląsk zaolziański, meaning "trans-Olza Silesia". Equivalent terms in other languages include Zaolší in...

, Southern Slovakia) were annexed by Poland and Hungary in the fall of 1938. The Zaolzie region was directly joined to the Third Reich after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939.

The German economy—burdened by heavy militarisation—urgently needed foreign currency. Setting up an artificially-high exchange rate between the Czechoslavak Koruna

Czechoslovak koruna

The Czechoslovak koruna was the currency of Czechoslovakia from April 10, 1919 to March 14, 1939 and from November 1, 1945 to February 7, 1993...

and the Reichsmark brought consumer goods to Germans (and soon created shortages in the Czech lands).

Czechoslovakia was a major manufacturer of machine guns, tanks, and artillery, most of which were assembled in the Škoda

Škoda Works

Škoda Works was the largest industrial enterprise in Austro-Hungary and later in Czechoslovakia, one of its successor states. It was also one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Europe in the 20th century...

factory and had a modern army of 35 divisions. Many of these factories continued to produce Czech designs until factories were converted for German designs. Czechoslovakia also had other major manufacturing companies. Entire steel and chemical factories were moved from Czechoslovakia and reassembled in Linz, Austria which incidentally remains a heavily industrialized sector of the country.

Czech resistance

František Moravec

František Moravec was Czechoslovak military intelligence officer before and during World War II....

—head of Czechoslovak military intelligence—organized and coordinated a resistance network. Hácha, Prime Minister Eliáš

Alois Eliáš

Alois Eliáš was a Czechoslovak general and politician. He served as Prime Minister of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from April 27, 1939 to September 28, 1941.- Career in 1939-1942 :...

, and the Czech resistance acknowledged Beneš's leadership. Active collaboration between London and the Czechoslovak home front was maintained throughout the war years. The most important event of the resistance was the Operation Anthropoid

Operation Anthropoid

Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the targeted killing of top German SS leader Reinhard Heydrich. He was the chief of the Reich Main Security Office , the acting Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, and a chief planner of the Final Solution, the Nazi German programme for the genocide of the...

, the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich , also known as The Hangman, was a high-ranking German Nazi official.He was SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei, chief of the Reich Main Security Office and Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia...

, SS

Schutzstaffel

The Schutzstaffel |Sig runes]]) was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under Heinrich Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during World War II...

leader Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

's deputy and the then Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. Infuriated, Hitler ordered the arrest and execution of 10,000 randomly selected Czechs, but, after consultations, he reduced his response. Over 10,000 were arrested, and at least 1,300 executed. The assassination resulted in one of the most well-known reprisals of the war. The village of Lidice

Lidice

Lidice is a village in the Czech Republic just northwest of Prague. It is built on the site of a previous village of the same name which, as part of the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, was on orders from Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, completely destroyed by German forces in reprisal...

and Ležáky

Ležáky

Ležáky was a village in Czechoslovakia. In 1942 it was razed to the ground by Nazis during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.Ležáky was a settlement inhabited by poor stone-cutters and little cottagers...

was completely destroyed by the Nazis; all men over 16 years of age from the village were murdered and the rest of the population was sent to Nazi concentration camps where many women and nearly all the children were killed.

The Czech resistance comprised four main groups:

- The army command coordinated with a multitude of spontaneous groupings to form the Defense of the Nation (Obrana národa, ON) with branches in Britain and France. Czechoslovak units and formations with overwhelming majority of Czechs (cca 82-85 %) served with the Polish Army (Czechoslovak LegionCzechoslovak Legion (1939)Czechoslovak Legion of 1939 was formed in Second Polish Republic after Germany occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939. While about 4000 Czechs and Slovaks joined the French Foreign Legion, about a 1000 chose to go to Poland, which looked likely to be involved in hostilities with Germany in the near...

), the French ArmyFrench ArmyThe French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

, the Royal Air ForceRoyal Air ForceThe Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

, the British ArmyBritish ArmyThe British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

(the 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade), and the Red ArmyRed ArmyThe Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

(I CorpsI Corps (Czechoslovakia)I Czechoslovak Army Corps was a unit of the Czechoslovak army in exile on the Eastern Front fighting alongside the Soviet Red Army, which was created on the April 10, 1944 at Chernivtsi and moved to Krosno area soon after....

). Thousands of Czech troops fought alongside the British during the war in areas such as North Africa and Palestine. Among other, Czech fighter pilot, sergeantSergeantSergeant is a rank used in some form by most militaries, police forces, and other uniformed organizations around the world. Its origins are the Latin serviens, "one who serves", through the French term Sergent....

Josef FrantišekJosef FrantišekSergeant Josef František DFM* was a Czech fighter pilot and World War II flying ace. He flew for the air forces of Czechoslovakia, Poland and the United Kingdom. He is famous as being the number one allied ace in the Battle of Britain.- Career :Born in Otaslavice in 1913, Josef František joined...

was one of the most famous Czech personalities as being the number one allied aceThe FewThe Few is a term used to describe the Allied airmen of the Royal Air Force who fought the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. It comes from Winston Churchill's phrase "Never, in the field of human conflict, was so much owed by so many to so few"....

in the Battle of BritainBattle of BritainThe Battle of Britain is the name given to the World War II air campaign waged by the German Air Force against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940...

.

- Beneš's collaborators, led by Prokop Drtina, created the Political Center (Politické ústředí, PÚ). The PÚ was nearly destroyed by arrests in November 1939, after which younger politicians took control.

- Social democrats and leftist intellectuals, in association with such groups as trade-unions and educational institutions, constituted the Committee of the Petition We Remain Faithful (Petiční výbor Věrni zůstaneme, PVVZ).

- The Communist Party of CzechoslovakiaCommunist Party of CzechoslovakiaThe Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, in Czech and in Slovak: Komunistická strana Československa was a Communist and Marxist-Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992....

(KSČ) was the fourth major resistance group. The KSČ had been one of over twenty political parties in the democratic First Republic, but it had never gained sufficient votes to unsettle the democratic government. After the Munich Agreement, the leadership of the KSČ moved to Moscow and the party went underground. Until 1943, however, KSČ resistance was weak. The Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression PactMolotov-Ribbentrop PactThe Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

in 1939 had left the KSČ in disarray. But ever faithful to the Soviet line, the KSČ began a more active struggle against the Nazis after Germany's attack on the Soviet UnionOperation BarbarossaOperation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

in June 1941.

The democratic groups—ON, PÚ, and PVVZ—united in early 1940 and formed the Central Committee of the Home Resistance (Ústřední výbor odboje domácího, ÚVOD). Involved primarily in intelligence gathering, the ÚVOD cooperated with a Soviet intelligence organization in Prague. Following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the democratic groups attempted to create a united front that would include the KSČ. Heydrich's appointment in the fall thwarted these efforts. By mid-1942, the Nazis had succeeded in exterminating the most experienced elements of the Czech resistance forces.

Czech forces regrouped in 1942–1943. The Council of the Three (R3)—in which the communist underground was also represented—emerged as the focal point of the resistance. The R3 prepared to assist the liberating armies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union. In cooperation with Red Army partisan units, the R3 developed a guerrilla structure.

Guerrilla activity intensified after the formation of a provisional Czechoslovak government in Košice

Košice

Košice is a city in eastern Slovakia. It is situated on the river Hornád at the eastern reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains, near the border with Hungary...

on 4 April 1945. "National committees" took over the administration of towns as the Germans were expelled. More than 4,850 such committees were formed between 1944 and the end of the war under the supervision of the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

. On 5 May, a national uprising

Prague uprising

The Prague uprising was an attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II. Events began on May 5, 1945, in the last moments of the war in Europe...

began spontaneously in Prague, and the newly formed Czech National Council (Česká národní rada) almost immediately assumed leadership of the revolt. Over 1,600 barricades were erected throughout the city, and some 30,000 Czech men and women battled for three days against 37,000–40,000 German troops backed by tanks and artillery. On 8 May, the German Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

capitulated; Soviet troops arrived on 9 May.

Slovak National Uprising

The Slovak National Uprising ("1944 Uprising") was an armed struggle between Nazi German Wehrmacht forces and rebel Slovak troops from August–October 1944. It was centered at Banská BystricaBanská Bystrica

Banská Bystrica is a key city in central Slovakia located on the Hron River in a long and wide valley encircled by the mountain chains of the Low Tatras, the Veľká Fatra, and the Kremnica Mountains. With 81,281 inhabitants, Banská Bystrica is the sixth most populous municipality in Slovakia...

.

The rebel Slovak Army, formed to fight the Nazis, had an estimated 18,000 soldiers in August, a total which first increased to 47,000 after mobilisation on 9 September 1944, and later to 60,000, plus 20,000 partisans. However, in late August, German troops were able to disarm the Eastern Slovak Army, which was the best equipped, and thus significantly decreased the power of the Slovak Army. Many members of this force were sent to concentration camps in the Third Reich; others escaped and joined partisan units or returned home.

The Slovaks were aided in the Uprising by soldiers and partisans from the Soviet Union, France, Czechia and Poland. In total, 32 nations were involved in the Uprising.

Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile

Edvard BenešEdvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

had resigned as president of the first Czechoslovak Republic on 5 October 1938 after the Nazi coup. In London, he and other Czechoslovak exiles organized a Czechoslovak government-in-exile and negotiated to obtain international recognition for the government and a renunciation of the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

and its consequences. After World War II broke out, a Czechoslovak national committee was constituted in France, and under Beneš's presidency sought international recognition as the exiled government of Czechoslovakia. This attempt led to some minor successes, such as the French-Czechoslovak treaty of 2 October 1939, which allowed for the reconstitution of the Czechoslovak army on French territory, yet full recognition was not reached. (The Czechoslovak army in France was established on 24 January 1940, and units of its 1st Infantry Division took part in the last stages of the Battle of France

Battle of France

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

, as did some Czechoslovak fighter pilots in various French Fighter squadrons.)

Beneš hoped for a restoration of the Czechoslovak state in its pre-Munich form after the anticipated Allied victory, a false hope. The government in exile—with Beneš as president of republic—was set up in June 1940 in exile in London, with the President living at Aston Abbotts

Aston Abbotts

Aston Abbotts is a village and civil parish within Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated about four miles north of Aylesbury and three miles south west of Wing. The parish had a population of 404 according to the 2001 census.The village name 'Aston' is a common one...

. On 18 July 1940, it was recognised by the British government. Belatedly, the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

(in the summer of 1941) and the U.S. (in winter) recognised the exiled government. In 1942, Allied repudiation of the Munich Agreement established the political and legal continuity of the First Republic and de jure

De jure

De jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

recognition of Beneš's de facto presidency. The success of the Operation Anthropoid

Operation Anthropoid

Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the targeted killing of top German SS leader Reinhard Heydrich. He was the chief of the Reich Main Security Office , the acting Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, and a chief planner of the Final Solution, the Nazi German programme for the genocide of the...

—which resulted in the British backed assassination of one of Hitler's top henchmen, Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich , also known as The Hangman, was a high-ranking German Nazi official.He was SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei, chief of the Reich Main Security Office and Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia...

, by Jozef Gabčík

Jozef Gabcík

Jozef Gabčík was a Slovak soldier of Czechoslovak army involved in Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich....

and Jan Kubiš

Jan Kubiš

Jan Kubiš was a Czech soldier, one of a team of Czechoslovak British-trained soldiers sent to assassinate acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, in 1942 as part of Operation Anthropoid.- Biography :Jan Kubiš was born in 1913 in Dolní Vilémovice,...

on 27 May—influenced the Allies in this repudiation.

The Munich Agreement had been precipitated by the subversive activities of the Sudeten Germans. During the latter years of the war, Beneš worked toward resolving the German minority problem and received consent from the Allies for a solution based on a postwar transfer of the Sudeten German population. The First Republic had been committed to a Western policy in foreign affairs. The Munich Agreement was the outcome. Beneš determined to strengthen Czechoslovak security against future German aggression through alliances with Poland and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union, however, objected to a tripartite Czechoslovak-Polish-Soviet commitment. In December 1943, Beneš's government concluded a treaty just with the Soviets.

Beneš's interest in maintaining friendly relations with the Soviet Union was motivated also by his desire to avoid Soviet encouragement of a post-war communist coup in Czechoslovakia. Beneš worked to bring Czechoslovak communist exiles in Britain into cooperation with his government, offering far-reaching concessions, including nationalization of heavy industry and the creation of local people's committees at the war's end. In March 1945, he gave key cabinet positions to Czechoslovak communist exiles in Moscow.

Czech resistance to Nazi occupation

Czech resistance to German Nazi occupation during World War II is a scarcely documented subject, by and large a result of little formal resistance and an effective German policy that deterred acts of resistance or annihilated organizations of resistance...

s demanded, based on German Nazi terror during occupation, the "final solution of the German question" which would have to be "solved" by deportation of the ethnic Germans from their homeland. These reprisals included massacres in villages Lidice

Lidice

Lidice is a village in the Czech Republic just northwest of Prague. It is built on the site of a previous village of the same name which, as part of the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, was on orders from Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, completely destroyed by German forces in reprisal...

and Ležáky

Ležáky

Ležáky was a village in Czechoslovakia. In 1942 it was razed to the ground by Nazis during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.Ležáky was a settlement inhabited by poor stone-cutters and little cottagers...

, although these villages were not connected with Czech resistance.

These demands were adopted by the Government-in-Exile, which sought the support of the Allies for this proposal, beginning in 1943. During the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile

Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile was an informal title conferred upon the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee, initially by British diplomatic recognition. The name came to be used by other World War II Allies as they subsequently recognized it...

promulgated a series of laws that are now referred to as the "Beneš decrees

Beneš decrees

Decrees of the President of the Republic , more commonly known as the Beneš decrees, were a series of laws that were drafted by the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile in the absence of the Czechoslovak parliament during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in World War II and issued by President...

". One part of these decrees dealt with the status of ethnic Germans and Hungarians in postwar Czechoslovakia, and laid the ground for the deportation

Deportation

Deportation means the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. Today it often refers to the expulsion of foreign nationals whereas the expulsion of nationals is called banishment, exile, or penal transportation...

of some 3,000,000 Germans and Hungarians from the land that had been their home for centuries (see expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and expulsions of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II....

, and Hungarians in Slovakia

Hungarians in Slovakia

Hungarians in Slovakia are the largest ethnic minority of the country, numbering 520,528 people or 9.7% of population . They are concentrated mostly in the southern part of the country, near the border with Hungary...

). The Beneš decrees declared that German property was to be confiscated without compensation. However, the final agreement authorizing the forced population transfer of the Germans was not reached until 2 August 1945 at the end of the Potsdam Conference.

End of the war

On 21 September, Czechoslovak troops formed in the Soviet Union liberated the village Kalinov

Kalinov

Kalinov can refer to several settlements:*in Slovakia:**Kalinov, a village in Medzilaborce District**a part of the municipality Krásno nad Kysucou*in Ukraine:**Kalyniv**a settlement in Sumska Oblast...

, the first liberated settlement of Czechoslovakia near the Dukla Pass

Dukla Pass

The Dukla Pass is a strategically significant mountain pass in the Laborec Highlands of the Outer Eastern Carpathians, on the border between Poland and Slovakia, and close to the western border of Ukraine....

in northeastern Slovakia. Czechoslovakia was liberated mostly by Soviet troops (the Red Army), supported by Czech and Slovak resistance, from the east to the west; only southwestern Bohemia was liberated by other Allied troops from the west. Except for the brutalities of the German occupation in Bohemia and Moravia (after the August 1944 Slovak National Uprising

Slovak National Uprising

The Slovak National Uprising or 1944 Uprising was an armed insurrection organized by the Slovak resistance movement during World War II. It was launched on August 29 1944 from Banská Bystrica in an attempt to overthrow the collaborationist Slovak State of Jozef Tiso...

also in Slovakia), Czechoslovakia suffered relatively little from the war. Even at the end of the war, German troops massacred Czech civilians, as was for example in Massacre in Trhová Kamenice

Massacre in Trhová Kamenice

Massacre in Trhová Kamenice happened on 8 May 1945 in what is now the Czech Republic.German troops, escaping from Chrudim back to Germany, passed through the village of Trhová Kamenice where they decided to punish supposed partisans...

or Massacre in Javoříčko.

A provisional Czechoslovak government was established by the Soviets in the eastern Slovak city of Košice on 4 April 1945. "National committees" (supervised by the Red Army) took over the administration of towns as the Germans were expelled. Bratislava

Bratislava

Bratislava is the capital of Slovakia and, with a population of about 431,000, also the country's largest city. Bratislava is in southwestern Slovakia on both banks of the Danube River. Bordering Austria and Hungary, it is the only national capital that borders two independent countries.Bratislava...

was taken by the Soviets on 4 April. Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

was taken on 9 May by Soviet troops during the Prague Offensive

Prague Offensive

The Prague Offensive was the last major Soviet operation of World War II in Europe. The offensive, and the battle for Prague, was fought on the Eastern Front from 6 May to 11 May 1945. This battle for the city is particularly noteworthy in that it ended after the Third Reich capitulated on 8 May...

. When the Soviets arrived, Prague was already in a general state of confusion due to the Prague Uprising

Prague uprising

The Prague uprising was an attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II. Events began on May 5, 1945, in the last moments of the war in Europe...

. Soviet and other Allied troops were withdrawn from Czechoslovakia in the same year.

Prague uprising

The Prague uprising was an attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II. Events began on May 5, 1945, in the last moments of the war in Europe...

(Czech: Pražské povstání) began. It was an attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II. The uprising went on until May 8, 1945, ending in a ceasefire the day before the arrival of the Red Army and one day after Victory in Europe Day.

It is estimated that about 345,000 World War II casualties

World War II casualties

World War II was the deadliest military conflict in history. Over 60 million people were killed, which was over 2.5% of the world population. The tables below give a detailed country-by-country count of human losses.-Total dead:...

were from Czechoslovakia, 277,000 of them Jews. As many as 144,000 Soviet troops died during the liberation of Czechoslovakia.

Annexation of Subcarpathian Ruthenia by the Soviet Union

In October 1944, Subcarpathian Ruthenia was taken by the Soviets. A Czechoslovak delegation under František Němec was dispatched to the area. The delegation was to mobilize the liberated local population to form a Czechoslovak army and to prepare for elections in cooperation with recently established national committees. Loyalty to a Czechoslovak state was tenuous in Carpathian Ruthenia. Beneš's proclamation of April 1944 excluded former collaborationist Hungarians, Germans and the Rusynophile Ruthenian followers of Andrej Brody and the Fencik Party (who had collaborated with the Hungarians) from political participation. This amounted to approximately ⅓ of the population. Another ⅓ was communist, leaving ⅓ of the population presumably sympathetic to the Czechoslovak Republic.Upon arrival in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the Czechoslovak delegation set up headquarters in Khust

Khust

Khust is a city located on the Khustets River in the Zakarpattia oblast in western Ukraine. It is near the confluence of the Tisza and Rika Rivers...

, and on 30 October issued a mobilization proclamation. Soviet military forces prevented both the printing and the posting of the Czechoslovak proclamation and proceeded instead to organize the local population. Protests from Beneš's government were ignored . Soviet activities led much of the local population to believe that Soviet annexation was imminent. The Czechoslovak delegation was also prevented from establishing a cooperative relationship with the local national committees promoted by the Soviets. On 19 November, the communists—meeting in Mukachevo—issued a resolution requesting separation of Subcarpathian Ruthenia from Czechoslovakia and incorporation into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. On 26 November, the Congress of National Committees unanimously accepted the resolution of the communists. The congress elected the National Council and instructed that a delegation be sent to Moscow to discuss union. The Czechoslovak delegation was asked to leave Subcarpathian Ruthenia. Negotiations between the Czechoslovak government and Moscow ensued. Both Czech and Slovak communists encouraged Beneš to cede Subcarpathian Ruthenia. The Soviet Union agreed to postpone annexation until the postwar period to avoid compromising Beneš's policy based on the pre-Munich frontiers.

The treaty ceding Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia is a region in Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast , with smaller parts in easternmost Slovakia , Poland's Lemkovyna and Romanian Maramureş.It is...

to the Soviet Union was signed in June 1945. Czechs and Slovaks living in Subcarpathian Ruthenia and Ruthenians (Rusyns

Rusyns

Carpatho-Rusyns are a primarily diasporic ethnic group who speak an Eastern Slavic language, or Ukrainian dialect, known as Rusyn. Carpatho-Rusyns descend from a minority of Ruthenians who did not adopt the use of the ethnonym "Ukrainian" in the early twentieth century...

) living in Czechoslovakia were given the choice of Czechoslovak or Soviet citizenship.

Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

(the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union) and presented plans for a "humane and orderly transfer" of the Sudeten German population. There were substantial exceptions from expulsions that applied to about 244,000 ethnic Germans who were allowed to remain in Czechoslovakia.

Following groups of ethnic Germans were not deported:

- anti-fascists

- persons crucial for industries

- those married with ethnic Czechs

It is estimated that between 700,000 and 800,000 Germans were affected by "wild" expulsions between May and August 1945. The expulsions were encouraged by Czechoslovak politicians and were generally carried out by the order of local authorities, mostly by groups of armed volunteers. However, in some cases it was initiated or pursued by assistance of the regular army.

The expulsion according the Potsdam Conference proceeded from 25 January 1946 till October of that year. An estimated 1.6 million ethnic Germans were deported to the American zone of what would become West Germany. An estimated 800,000 were deported to the Soviet zone (in what would become East Germany).http://www.radio.cz/en/article/65421 Several thousand died violently during the expulsion and many more died from hunger and illness as a consequence. These casualties include violent deaths and suicides, deaths in "internment camps" and natural causes. The joint Czech-German commission of historians stated in 1996 following numbers: The deaths caused by violence and abnormal living conditions amount approximately to 10 000 persons killed. Another 5,000–6,000 people died of unspecified reasons related to expulsion making the total amount of victims of the expulsion 15,000-16 000 (this excludes suicides, which make another approximately 3,400 cases).

Approximately 225,000 Germans remained in Czechoslovakia, of whom 50,000 emigrated or were expelled soon after.

See also

- Fall Grün, the Nazi invasion plan for Czechoslovakia rendered obsolete by the Munich Agreement.

- Concentration camps Lety and Hodonín in the Czech republicConcentration camps Lety and HodonínThe concentration camp in Lety was a World War II internment camp for Romani people from the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia on July 10, 1942.- Background :...

- Czechoslovak border fortificationsCzechoslovak border fortificationsThe Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

– built 1935–1938 against Nazi Germany - Karel PavlíkKarel PavlíkKarel Pavlík was a Czechoslovak Army captain and decorated hero of Czechoslovakia....

- Western betrayalWestern betrayalWestern betrayal, also called Yalta betrayal, refers to a range of critical views concerning the foreign policies of several Western countries between approximately 1919 and 1968 regarding Eastern Europe and Central Europe...