Sudetenland

Encyclopedia

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

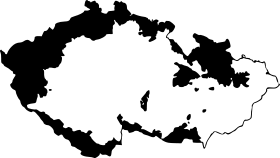

name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

, and those parts of Silesia

Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia is an unofficial name of one of the three Czech lands and a section of the Silesian historical region. It is located in the north-east of the Czech Republic, predominantly in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with a section in the northern Olomouc Region...

being within Czechoslovakia.

The name is derived from the Sudeten mountains

Sudeten mountains

The Sudetes is a mountain range in Central Europe. It is also known as the Sudeten or Sudety Mountains....

, though the Sudetenland extended beyond these mountains which run along the border to Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

and contemporary Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

. The German inhabitants were called Sudeten Germans

Sudeten Germans

- Importance of Sudeten Germans :Czechoslovakia was inhabited by over 3 million ethnic Germans, comprising about 23 percent of the population of the republic and about 29.5% of Bohemia and Moravia....

(German: Sudetendeutsche, Czech: Sudetští Němci, Polish: Niemcy Sudeccy). The German minority in Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

, the Carpathian Germans

Carpathian Germans

Carpathian Germans , sometimes simply called Slovak Germans , are a group of German language speakers on the territory of present-day Slovakia...

, is not included in this ethnic category.

History

The areas later known as Sudetenland never formed a single historical regionHistorical regions of Central Europe

There are many historical regions of Central Europe. For the purpose of this list, Central Europe is defined as the area contained roughly within the south coast of the Baltic Sea, the Elbe River, the Alps, the Danube River, the Black Sea and the Dnepr River. Note that these regions come from...

, which makes it difficult to distinguish the history of the Sudetenland apart from that of Bohemia, until the advent of and coining of the term nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

in the 19th century.

Early origins

In the Late Middle AgesLate Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages was the period of European history generally comprising the 14th to the 16th century . The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern era ....

the regions situated on the mountainous border of the Kingdom of Bohemia

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia was a country located in the region of Bohemia in Central Europe, most of whose territory is currently located in the modern-day Czech Republic. The King was Elector of Holy Roman Empire until its dissolution in 1806, whereupon it became part of the Austrian Empire, and...

were since the Migration Period

Migration Period

The Migration Period, also called the Barbarian Invasions , was a period of intensified human migration in Europe that occurred from c. 400 to 800 CE. This period marked the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages...

settled mainly by western Slavic Czechs. Along the Bohemian Forest

Bohemian Forest

The Bohemian Forest, also known in Czech as Šumava , is a low mountain range in Central Europe. Geographically, the mountains extend from South Bohemia in the Czech Republic to Austria and Bavaria in Germany...

in the west, the Czech lands

Czech lands

Czech lands is an auxiliary term used mainly to describe the combination of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia. Today, those three historic provinces compose the Czech Republic. The Czech lands had been settled by the Celts , then later by various Germanic tribes until the beginning of 7th...

bordered on the German stem duchies

Stem duchy

Stem duchies were essentially the domains of the old German tribes of the area, associated with the Frankish Kingdom, especially the East, in the Early Middle Ages. These tribes were originally the Franks, the Saxons, the Alamanni, the Burgundians, the Thuringii, and the Rugii...

of Bavaria

History of Bavaria

The history of Bavaria stretches from its earliest settlement and its formation as a stem duchy in the 6th century through its inclusion in the Holy Roman Empires to its status as an independent kingdom and, finally, as a large and significant Bundesland of the modern Federal Republic of...

and Franconia

Franconia

Franconia is a region of Germany comprising the northern parts of the modern state of Bavaria, a small part of southern Thuringia, and a region in northeastern Baden-Württemberg called Tauberfranken...

; marches of the medieval German kingdom

Kingdom of Germany

The Kingdom of Germany developed out of the eastern half of the former Carolingian Empire....

had also been established in the adjacent Austrian

March of Austria

The March of Austria was created in 976 out of the territory that probably formed the earlier March of Pannonia. It is also called the Margraviate of Austria or the Bavarian Eastern March. In contemporary Latin, it was the marchia Austriae, Austrie marchionibus, or the marcha Orientalis...

lands south of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands

Bohemian-Moravian Highlands

The Bohemian-Moravian Highlands is an extensive range of hills and low mountains over long, which runs in a northeasterly direction across the Czech Republic and forms the border between Bohemia and Moravia...

and the northern Meissen region beyond the Ore Mountains

Ore Mountains

The Ore Mountains in Central Europe have formed a natural border between Saxony and Bohemia for many centuries. Today, the border between Germany and the Czech Republic runs just north of the main crest of the mountain range...

. In the course of the Ostsiedlung

Ostsiedlung

Ostsiedlung , also called German eastward expansion, was the medieval eastward migration and settlement of Germans from modern day western and central Germany into less-populated regions and countries of eastern Central Europe and Eastern Europe. The affected area roughly stretched from Slovenia...

, German settlers from the 13th century on also moved into the Upper Lusatia

Upper Lusatia

Upper Lusatia is a region a biggest part of which belongs to Saxony, a small eastern part belongs to Poland, the northern part to Brandenburg. In Saxony, Upper Lusatia comprises roughly the districts of Bautzen and Görlitz , in Brandenburg the southern part of district Oberspreewald-Lausitz...

region and Duchy of Silesia

Duchy of Silesia

The Duchy of Silesia with its capital at Wrocław was a medieval duchy located in the historic Silesian region of Poland. Soon after it was formed under the Piast dynasty in 1138, it fragmented into various Duchies of Silesia. In 1327 the remaining Duchy of Wrocław as well as most other duchies...

north of the Sudetes mountain range.

Already from the second half of the 13th century onwards these Bohemian border regions were settled by Ethnic Germans, who were invited by the Přemyslid

Premyslid dynasty

The Přemyslids , were a Czech royal dynasty which reigned in Bohemia and Moravia , and partly also in Hungary, Silesia, Austria and Poland.-Legendary rulers:...

Bohemian kings — especially by Ottokar II

Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II , called The Iron and Golden King, was the King of Bohemia from 1253 until 1278. He was the Duke of Austria , Styria , Carinthia and Carniola also....

(1253-1278) and Wenceslaus II (1278-1305). Ottokar in 1257 expelled the Czech population from the Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

quarter Malá Strana

Malá Strana

Malá Strana is a district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic, and one of its most historic regions.The name translated into English literally means "Little Side", though it is frequently referred to as "Lesser Town", "Lesser Quarter", or "Lesser Side"...

(Lesser Town) to establish the Nova civitas sub castro Pragensis ("New City under the Prague Castle

Prague Castle

Prague Castle is a castle in Prague where the Kings of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors and presidents of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic have had their offices. The Czech Crown Jewels are kept here...

") settled by German colonists and vested with Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg Rights or Magdeburg Law were a set of German town laws regulating the degree of internal autonomy within cities and villages granted by a local ruler. Modelled and named after the laws of the German city of Magdeburg and developed during many centuries of the Holy Roman Empire, it was...

.

After the extinction of the Přemyslid dynasty in 1306, the Bohemian nobility backed the John of Luxembourg to assume the rule against his rival Duke Henry of Carinthia. In 1322 King John acquired (for the third time) the formerly Imperial Egerland

Egerland

The Egerland is a historical region in the far north west of Bohemia in the Czech Republic at the border with Germany. It is named after the German name Eger for the city of Cheb and the main river Ohře...

region in the west and was able to vassalize most of the Piast

Silesian Piasts

The Silesian Piasts were the oldest line of the Piast dynasty beginning with Władysław II the Exile, son of Bolesław III Wrymouth, Duke of Poland...

Silesian duchies, acknowledged by King Casimir III of Poland

Casimir III of Poland

Casimir III the Great , last King of Poland from the Piast dynasty , was the son of King Władysław I the Elbow-high and Hedwig of Kalisz.-Biography:...

by the 1335 Treaty of Trentschin. His son King Charles IV

Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles IV , born Wenceslaus , was the second king of Bohemia from the House of Luxembourg, and the first king of Bohemia to also become Holy Roman Emperor....

was elected King of the Romans

King of the Romans

King of the Romans was the title used by the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire following his election to the office by the princes of the Kingdom of Germany...

in 1346 and crowned Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

in 1355. He added the Lusatia

Lusatia

Lusatia is a historical region in Central Europe. It stretches from the Bóbr and Kwisa rivers in the east to the Elbe valley in the west, today located within the German states of Saxony and Brandenburg as well as in the Lower Silesian and Lubusz voivodeships of western Poland...

s to the Lands of the Bohemian Crown

Lands of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown , also called the Lands of the Crown of Saint Wenceslas or simply the Bohemian Crown or Czech Crown lands , refers to the area connected by feudal relations under the joint rule of the Bohemian kings...

, which then comprised large territories with a significant German population.

In the hilly border regions German settlers established major manufactures of forest glass

Forest glass

The term Forest glass or the German name Waldglas is given to late Medieval glass produced in North-Western Europe from about 1000-1700 AD using wood ash and sand as the main raw materials and made in factories known as glass-houses in forest areas...

. The situation of the German population was aggravated by the Hussite Wars

Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars involved the military actions against and amongst the followers of Jan Hus in Bohemia in the period 1419 to circa 1434. The Hussite Wars were notable for the extensive use of early hand-held gunpowder weapons such as hand cannons...

(1419–1434), though there were also some Germans among the Hussite

Hussite

The Hussites were a Christian movement following the teachings of Czech reformer Jan Hus , who became one of the forerunners of the Protestant Reformation...

insurgents.

By then Germans largely settled the hilly Bohemian border regions as well as the cities of the lowlands; mainly people of Bavarian descent in the South Bohemian

South Bohemian Region

South Bohemian Region is an administrative unit of the Czech Republic, located mostly in the southern part of its historical land of Bohemia, with a small part in southwestern Moravia...

and South Moravian Region

South Moravian Region

South Moravian Region is an administrative unit of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia, with exception of Jobova Lhota, that belongs to Bohemia. Its capital is Brno the 2nd largest city of the Czech Republic. The region is famous for its wine...

, in Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

, in Jihlava

Jihlava

Jihlava is a city in the Czech Republic. Jihlava is a centre of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava river on the ancient frontier between Moravia and Bohemia, and is the oldest mining town in the Czech Republic, ca. 50 years older than Kutná Hora.Among the principal buildings are the...

, České Budějovice

Ceské Budejovice

České Budějovice is a city in the Czech Republic. It is the largest city in the South Bohemian Region and is the political and commercial capital of the region and centre of the Roman Catholic Diocese of České Budějovice and of the University of South Bohemia and the Academy of Sciences...

and the West Bohemian Plzeň Region

Plzen Region

Plzeň Region is an administrative unit in the western part of Bohemia in the Czech Republic. It is named after its capital Plzeň .- Communes :...

; Franconian people in Žatec

Žatec

Žatec is an old town in the Czech Republic, in Louny District, Ústí nad Labem Region. It has a population of 19,813 .The earliest historical reference to Sacz is in the Latin chronicle of Thietmar of Merseburg of 1004. During the 11th century it belonged to the Vršovci - a powerful Czech...

; Upper Saxons

Upper Saxony

Upper Saxony was a name given to the majority of the German lands held by the House of Wettin, in what is now called Mitteldeutschland....

in adjacent North Bohemia

North Bohemia

North Bohemia , is a region in the north of the Czech Republic.- Location :North Bohemia roughly covers the present-day NUTS regional unit of CZ04 Severozápad and the western part of CZ05 Severovýchod....

, where the border with the Saxon Electorate

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony , sometimes referred to as Upper Saxony, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire. It was established when Emperor Charles IV raised the Ascanian duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg to the status of an Electorate by the Golden Bull of 1356...

was fixed with the signing of the 1459 Peace of Eger

Treaty of Eger

The Treaty of Eger was concluded on 25 April 1459 in Eger . The treaty established the border between Bohemia and the Electorate of Saxony on the heights of the Ore Mountains and the middle of the River Elbe. This border remains largely unchanged today...

; Germanic Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

ns in the adjacent Sudetes region with the County of Kladsko

County of Kladsko

The County of Kladsko was a historical administrative unit in the Kingdom of Bohemia and later in the Kingdom of Prussia with its capital at Kłodzko on the Nysa river...

, in the Moravian–Silesian Region, in Svitavy

Svitavy

Svitavy is a town in the Svitavy District in the Pardubice Region of the Czech Republic. The town has a population of 18,000 and is also the district administrative centre...

and Olomouc

Olomouc

Olomouc is a city in Moravia, in the east of the Czech Republic. The city is located on the Morava river and is the ecclesiastical metropolis and historical capital city of Moravia. Nowadays, it is an administrative centre of the Olomouc Region and sixth largest city in the Czech Republic...

. The City of Prague had since the last third of 17th century till 1860 a German speaking majority.

From the Luxembourgs, the rule over Bohemia passed through George of Podiebrad to the Polish-Lithuanian Jagiellon dynasty

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty was a royal dynasty originating from the Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century...

and finally to the House of Habsburg in 1526. From the loss of the Bohemian Revolt that shattered at the 1620 Battle of White Mountain

Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain, 8 November 1620 was an early battle in the Thirty Years' War in which an army of 30,000 Bohemians and mercenaries under Christian of Anhalt were routed by 27,000 men of the combined armies of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor under Charles Bonaventure de Longueval,...

, the Habsburgs gradually integrated the Kingdom of Bohemia into their Monarchy

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

. Both Czech and German Bohemians suffered heavily in the Thirty Years War. During the subsequent Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation was the period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent and ending at the close of the Thirty Years' War, 1648 as a response to the Protestant Reformation.The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort, composed of four major elements:#Ecclesiastical or...

, abandoned areas were re-settled with Catholic Germans from the Austrian lands. Since 1627 the Habsburgs enforced the so-called Verneuerte Landesordnung ("Renewed Land's Constitution") and one of its consequences was that the German gradually became the main official language and Czech declined to a secondary role. Emperor Joseph II

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I...

in 1780 renounced the coronation ceremony as Bohemian king and unsuccessfully tried to push German through as sole official language in all Habsburg lands (including Hungary), nevertheless the German cultural influence grew stronger during the Age of Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

and Weimar Classicism

Weimar Classicism

Weimar Classicism is a cultural and literary movement of Europe. Followers attempted to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical and Enlightenment ideas...

.

On the other hand, in the course of the Romanticism

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

movement national tensions arose, both in the form of the Austroslavism

Austroslavism

Austroslavism was a political concept and program aimed to solve problems of Slavic peoples in the Austrian Empire.It was most influential among Czech liberals around the middle of the 19th century...

ideology developed by Czech politicians like František Palacký

František Palacký

František Palacký was a Czech historian and politician.-Biography:...

and Pan-Germanist

German nationalism in Austria

German nationalism is a political ideology and a current in Austrian politics. It has its origins in the German National Movement of the 19th century, a nationalist movement of the German-speaking population in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and had striven for a closer connection of the...

activist raising the German question

German question

The German question was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve the Unification of Germany. From 1815–1871, a number of 37 independent German-speaking states existed within the German Confederation...

. Conflicts between Czech and German nationalists emerged in the 19th century, for instance in the Revolutions of 1848

Revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements. Much of the revolutionary activity was of a nationalist character: the empire, ruled from Vienna, included Austrian Germans, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenians,...

: while the German-speaking population of Bohemia and Moravia wanted to participate in the building of a German nation state, the Czech-speaking population insisted on keeping Bohemia out of such plans. Bohemia remained a part of the Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

until its dismemberment after the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

.

Emergence of the term

World War I and its aftermath

During the First World War, the Sudetenland experienced a rate of war deaths higher than most other German speaking areas of Austria-HungaryAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

and exceeded only by German South Moravia

German South Moravia

German South Moravia was a historical region of Czechoslovakia. It includes parts of southern and western Moravia once largely populated by ethnic Germans.-History:...

and Carinthia

Duchy of Carinthia

The Duchy of Carinthia was a duchy located in southern Austria and parts of northern Slovenia. It was separated from the Duchy of Bavaria in 976, then the first newly created Imperial State beside the original German stem duchies....

. Thirty-four of each 1,000 inhabitants were killed.

After World War I, Austria-Hungary broke apart. Late in October 1918, an independent Czechoslovak

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

state, consisting of the lands of the Bohemian kingdom and areas belonging to the Kingdom of Hungary, was proclaimed. The German deputies of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia in the Imperial Council (Reichsrat) referred to the Fourteen Points

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe...

of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

and the right proposed therein to self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

, and attempted to negotiate the union of the German-speaking territories with the new Republic of German Austria

German Austria

Republic of German Austria was created following World War I as the initial rump state for areas with a predominantly German-speaking population within what had been the Austro-Hungarian Empire, without the Kingdom of Hungary, which in 1918 had become the Hungarian Democratic Republic.German...

, which itself aimed at joining Weimar Germany

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

.

However Sudetenland remained in a newly created Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, a multi-ethnic state of several nations: Czechs, Germans

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

, Slovaks

Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people, or Slovakians are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia...

, Hungarians, Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

and Ruthenians

Ruthenians

The name Ruthenian |Rus']]) is a culturally loaded term and has different meanings according to the context in which it is used. Initially, it was the ethnonym used for the East Slavic peoples who lived in Rus'. Later it was used predominantly for Ukrainians...

. On 20 September 1918, the Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

Government asked the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

's opinion for the Sudetenland. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

sent ambassador Archibald Coolidge into the Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. After Coolidge became witness of Sudetengerman demonstrations , Coolidge suggested the possibility of ceding certain German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

-speaking parts of Bohemia to Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

(Cheb) and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

(South Moravia and South Bohemia). He also insisted that the German inhabited regions of West and North Bohemia remain within Czechoslovakia. However, the American delegation at the Paris talks, with Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles was an American diplomat, lawyer, banker, and public official who became the first civilian and the longest-serving Director of Central Intelligence and a member of the Warren Commission...

as the American's chief diplomat who emphasized preserving the unity of the Czech lands, decided not to follow Coolidge's proposal.

Four regional governmental units were established:

- German BohemiaGerman BohemiaGerman Bohemia was a region in Czech Republic established, for a short period of time, after World War I. It included parts of northern and western Bohemia once largely populated by ethnic Germans...

(Deutschböhmen), the regions of northern and western Bohemia; proclaimed a constitutive state (Land) of the German-Austrian Republic with ReichenbergLiberecLiberec is a city in the Czech Republic. Located on the Lusatian Neisse and surrounded by the Jizera Mountains and Ještěd-Kozákov Ridge, it is the fifth-largest city in the Czech Republic....

as capital, administered by a LandeshauptmannLandeshauptmannLandeshauptmann is a former German gubernatorial title equivalent to that of a governor of a province or a state....

(state captain), consecutively: Rafael Pacher (1857–1936), 29 October-6 November 1918, and Rudolf Ritter von Lodgman von Auen (1877–1962), 6 November-16 December 1918 (the last principal city was conquered by the Czech army but he continued in exile, first at Zittau in Saxony and then in Vienna, until 24 September 1919) - Province Sudetenland, the regions of northern MoraviaMoraviaMoravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

and Austrian SilesiaAustrian SilesiaAustrian Silesia , officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia was an autonomous region of the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Austrian Empire, from 1867 a Cisleithanian crown land of Austria-Hungary...

; proclaimed a constituent state of the German-Austrian Republic with TroppauOpavaOpava is a city in the northern Czech Republic on the river Opava, located to the north-west of Ostrava. The historical capital of Czech Silesia, Opava is now in the Moravian-Silesian Region and has a population of 59,843 as of January 1, 2005....

as capital, governed by a Landeshauptmann: Robert Freissler (1877–1950), 30 October-18 December 1918 - Bohemian Forest RegionBohemian Forest RegionThe Bohemian Forest Region is a historical region in the Czech Republic. It includes parts of southwestern Bohemia in the Bohemian Forest once largely populated by ethnic Germans.-History:...

(Böhmerwaldgau), the region of Bohemian ForestBohemian ForestThe Bohemian Forest, also known in Czech as Šumava , is a low mountain range in Central Europe. Geographically, the mountains extend from South Bohemia in the Czech Republic to Austria and Bavaria in Germany...

/South Bohemia; proclaimed a district (Kreis) of the existing Austrian Land of Upper AustriaUpper AustriaUpper Austria is one of the nine states or Bundesländer of Austria. Its capital is Linz. Upper Austria borders on Germany and the Czech Republic, as well as on the other Austrian states of Lower Austria, Styria, and Salzburg...

; administered by Kreishauptmann (district captain): Friedrich Wichtl (1872–1922) from 30 October 1918 - German South MoraviaGerman South MoraviaGerman South Moravia was a historical region of Czechoslovakia. It includes parts of southern and western Moravia once largely populated by ethnic Germans.-History:...

(Deutschsüdmähren), proclaimed a District (Kreis) of the existing Austrian land Lower AustriaLower AustriaLower Austria is the northeasternmost state of the nine states in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria since 1986 is Sankt Pölten, the most recently designated capital town in Austria. The capital of Lower Austria had formerly been Vienna, even though Vienna is not officially part of Lower Austria...

, administered by a Kreishauptmann: Oskar Teufel (1880–1946) from 30 October 1918.

The U.S. commission to the Paris Peace Conference

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

issued a declaration which gave unanimous support for "unity of Czech lands". In particular the declaration stated:

Several German minorities

Ethnic German

Ethnic Germans historically also ), also collectively referred to as the German diaspora, refers to people who are of German ethnicity. Many are not born in Europe or in the modern-day state of Germany or hold German citizenship...

in Moravia, including German populations in Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

, Jihlava

Jihlava

Jihlava is a city in the Czech Republic. Jihlava is a centre of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava river on the ancient frontier between Moravia and Bohemia, and is the oldest mining town in the Czech Republic, ca. 50 years older than Kutná Hora.Among the principal buildings are the...

, and Olomouc

Olomouc

Olomouc is a city in Moravia, in the east of the Czech Republic. The city is located on the Morava river and is the ecclesiastical metropolis and historical capital city of Moravia. Nowadays, it is an administrative centre of the Olomouc Region and sixth largest city in the Czech Republic...

also attempted to proclaim their union with German Austria, but failed.

The Czechs thus rejected the aspirations of the Sudeten Germans and demanded the inclusion of the Sudetenland in their state, despite the presence of more than 90% (as of 1921) ethnic Germans (which led to the presence of 23.4% Germans in all of Czechoslovakia), on the grounds they had always been part of Czech lands. The Treaty of Saint-Germain

Treaty of Saint-Germain

The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, was signed on 10 September 1919 by the victorious Allies of World War I on the one hand and by the new Republic of Austria on the other...

in 1919 affirmed the inclusion of the German-speaking territories within the Czechoslovakia.

However, over the next two decades, some Germans in the Sudetenland continued to strive for a separation of the German inhabited regions from Czechoslovakia.

Within the Czechoslovak Republic (1918-1938)

According to the February 1921 census, 3,123,000 Germans lived in all Czechoslovakia — 23.4% of the total population. The controversies between the Czechs and the German minority (which constituted a majority in the Sudetenland areas) lingered on throughout the 1920s, and intensified in the 1930s.During the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

the mostly mountainous regions populated by the German minority, together with other peripheral regions of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, were hurt by the economic depression more than the interior of the country. Unlike the less developed regions (Ruthenia

Ruthenia

Ruthenia is the Latin word used onwards from the 13th century, describing lands of the Ancient Rus in European manuscripts. Its geographic and culturo-ethnic name at that time was applied to the parts of Eastern Europe. Essentially, the word is a false Latin rendering of the ancient place name Rus...

, Moravian Wallachia), the Sudetenland had a high concentration of vulnerable export-dependent industries (such as glass works, textile industry

Textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the production of yarn, and cloth and the subsequent design or manufacture of clothing and their distribution. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry....

, paper-making and toy-making industry). Sixty percent of the bijouterie and glass-making industry were located in the Sudetenland, 69% of employees in this sector were Germans, and 95% of bijouterie and 78% of other glassware was produced for export. The glass-making sector was affected by decreased spending power and also by protective measures in other countries and many German workers lost their work.

The high unemployment made people more open to populist and extremist movements (Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, Fascism

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

and German irredentism

Irredentism

Irredentism is any position advocating annexation of territories administered by another state on the grounds of common ethnicity or prior historical possession, actual or alleged. Some of these movements are also called pan-nationalist movements. It is a feature of identity politics and cultural...

). In these years, the parties of German nationalists and later the Sudetendeutsche Party

Sudeten German National Socialist Party

The Sudeten German Party was created by Konrad Henlein under the name Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront on October 1, 1933, some months after the state of Czechoslovakia had outlawed the German National Socialist Workers' Party...

(SdP) with its radical demands gained immense popularity among Germans in Czechoslovakia

Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)

From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 3 million ethnic Germans were living in what became the Czech lands of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia. Ethnic Germans had lived in Bohemia, a part of the Holy Roman Empire, since the 14th century , mostly in...

.

Sudeten Crisis

The increasing aggressiveness of Hitler prompted the Czechoslovak military to build extensive Czechoslovak border fortificationsCzechoslovak border fortifications

The Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

starting in 1936 to defend the troubled border region.

Immediately after the Anschluss

Anschluss

The Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

of Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

into the Third Reich in March 1938, Hitler made himself the advocater of ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, triggering the "Sudeten Crisis

German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

". The following month, Sudeten Nazis, led by Konrad Henlein

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

, agitated for autonomy. On 24 April 1938 the SdP proclaimed the Karlovy Vary Programme (Karlsbader Programm), which demanded in eight points the complete equality between the Sudetengermans and the Czech people. The government accepted these claims on June 30, 1937.

In August, UK Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

, sent Lord Runciman

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford PC was a prominent Liberal, later National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom from the 1900s until the 1930s.-Background:...

to Czechoslovakia in order to see if he could obtain a settlement between the Czechoslovak government and the Germans in the Sudetenland. Lord Runciman's first day included meetings with President Beneš and Prime Minister Milan Hodža as well as a direct meeting with the Sudeten Germans from Henlein's SdP. On the next day he met with Dr and Mme Beneš and later met non-Nazi Germans in his hotel http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,788287-1,00.html

A full account of his report — including summaries of the conclusions of his meetings with the various parties — which he made in person to the Cabinet on his return to Britain is found in the Document CC 39(38). Lord Runciman expressed sadness that he could not bring about agreement with the various parties, but he agreed with Lord Halifax that the time gained was important. He reported on the situation of the Sudeten Germans, and he gave details of four plans which had been proposed to deal with the crisis, each of which had points which, he reported, made it unacceptable to the other parties to the negotiations. The four were: Transfer of the Sudetenland to the Reich; hold a plebiscite on the transfer of the Sudetenland to the Reich, organize a Four Power Conference on the matter, create a federal Czechoslovakia. At the meeting, he said that he was very reluctant to offer his own solution; he had not seen this as his task. The most that he said was that the great centres of opposition were in Eger and Asch, in the north-western corner of Bohemia, which contained about 800,000 Germans and very few others. He did say that the transfer of these areas to Germany would almost certainly be a good thing; however, he did add that the Czechoslovak army would certainly oppose this very strongly, and that Dr. Beneš had said that they would fight rather than accept it.

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

met with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

in Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden is a municipality in the German Bavarian Alps. It is located in the south district of Berchtesgadener Land in Bavaria, near the border with Austria, some 30 km south of Salzburg and 180 km southeast of Munich...

on 15 September and agreed to the cession

Cession

The act of Cession, or to cede, is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty...

of the Sudetenland. Three days later, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

did the same. No Czechoslovak representative was invited to these discussions.

Chamberlain met Hitler in Godesberg

Bad Godesberg

Bad Godesberg is a municipal district of Bonn, southern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. From 1949 till 1990 , the majority of foreign embassies to Germany were located in Bad Godesberg...

on September 22 to confirm the agreements. Hitler however, aiming to use the crisis as a pretext for war, now demanded not only the annexation of the Sudetenland but the immediate military occupation of the territories, giving the Czechoslovak army no time to adapt their defence measures to the new borders. To achieve a solution, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

suggested a conference of the major powers in Munich and on September 29, Hitler, Daladier and Chamberlain met and agreed to Mussolini's proposal (actually prepared by Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

) and signed the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

, accepting the immediate occupation of the Sudetenland. The Czechoslovak government, though not party to the talks, submitted to compulsion and promised to abide by the agreement on September 30.

The Sudetenland was relegated to Germany between October 1 and October 10, 1938. The Czech part of Czechoslovakia was subsequently invaded by Germany

German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

in March 1939, with a portion being annexed and the remainder turned into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

. The Slovak part declared its independence from Czechoslovakia, becoming the Slovak Republic (Slovak State), a satellite state and ally of Nazi Germany. (Ruthenian part — Subcarpathian Rus — made also an attempt to declare its sovereignty as Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine was an autonomous region within Czechoslovakia from late 1938 to March 15, 1939. It declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939, but was occupied by Hungary between March 15 and March 18, 1939, remaining under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in...

but only with ephemeral success. This area was annexed by Hungary.)

Part of the borderland was also invaded and annexed by Poland.

Sudetenland as part of Nazi Germany

The Sudetenland was initially put under military administration, with General Wilhelm KeitelWilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Gustav Keitel was a German field marshal . As head of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht and de facto war minister, he was one of Germany's most senior military leaders during World War II...

as Military governor. On 21 October 1938, the annexed territories were divided, with the southern parts being incorporated into the neighbouring Reichsgaue Oberdonau and Niederdonau.

The northern and western parts were reorganized as the Reichsgau Sudetenland, with the city of Reichenberg (present-day Liberec

Liberec

Liberec is a city in the Czech Republic. Located on the Lusatian Neisse and surrounded by the Jizera Mountains and Ještěd-Kozákov Ridge, it is the fifth-largest city in the Czech Republic....

) established as its capital. Konrad Henlein

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

(now openly a NSDAP member) administered the district first as Reichskommissar

Reichskommissar

Reichskommissar , in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and the Nazi Third Reich....

(until 1 May 1939) and then as Reichsstatthalter

Reichsstatthalter

The term Reichsstatthalter was used twice for different offices, in the imperial Hohenzollern dynasty's German Empire and the single-party Nazi Third Reich.- "Statthalter des Reiches" 1879-1918 in Alsace-Lorraine :...

(1 May 1939–4 May 1945). Sudetenland consisted of three political districts: Eger

Egerland

The Egerland is a historical region in the far north west of Bohemia in the Czech Republic at the border with Germany. It is named after the German name Eger for the city of Cheb and the main river Ohře...

(with Karlsbad

Karlovy Vary

Karlovy Vary is a spa city situated in western Bohemia, Czech Republic, on the confluence of the rivers Ohře and Teplá, approximately west of Prague . It is named after King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, who founded the city in 1370...

as capital), Aussig

Ústí nad Labem Region

Ústí nad Labem Region is an administrative unit of the Czech Republic, located in the north-western part of its historical region of Bohemia...

(Aussig

Ústí nad Labem

Ústí nad Labem is a city of the Czech Republic, in the Ústí nad Labem Region. The city is the 7th-most populous in the country.Ústí is situated in a mountainous district at the confluence of the Bílina and the Elbe Rivers, and, besides being an active river port, is an important railway junction...

) and Troppau

Opava District

Opava District is a district within Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. Its capital is Opava.- Complete list of municipalities :Bělá -Bohuslavice -Bolatice -Branka u Opavy -Bratříkovice -Brumovice -Březová -...

(Troppau

Opava

Opava is a city in the northern Czech Republic on the river Opava, located to the north-west of Ostrava. The historical capital of Czech Silesia, Opava is now in the Moravian-Silesian Region and has a population of 59,843 as of January 1, 2005....

).

Shortly after the annexation, the Jews living in the Sudetenland were widely persecuted. Only a few weeks afterwards, the Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht

Kristallnacht, also referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, and also Reichskristallnacht, Pogromnacht, and Novemberpogrome, was a pogrom or series of attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and parts of Austria on 9–10 November 1938.Jewish homes were ransacked, as were shops, towns and...

occurred. As elsewhere in Germany, many synagogues were set on fire and numerous leading Jews were sent to concentration camps

Nazi concentration camps

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

. In later years, the Nazis transported up to 300,000 Czech and Slovak Jews to concentration camps.

Nazi concentration camps

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

where many of them were killed or died. Jews and Czechs were not the only afflicted peoples; German socialists, communists and pacifists were widely persecuted as well. Some of the German Socialists fled the Sudetenland via Prague and London to other countries. The Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung , meaning "coordination", "making the same", "bringing into line", is a Nazi term for the process by which the Nazi regime successively established a system of totalitarian control and tight coordination over all aspects of society. The historian Richard J...

would permanently alter the community in the Sudetenland.

Despite this, on 4 December 1938 there were elections in Reichsgau Sudetenland, in which 97.32% of the adult population voted for NSDAP. About a half million Sudeten Germans joined the Nazi Party which was 17.34% of the total German population in Sudetenland (the average NSDAP membership participation in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

was merely 7.85% in 1944). This means the Sudetenland was one of the most pro-Nazi regions of the Third Reich. Because of their knowledge of the Czech language

Czech language

Czech is a West Slavic language with about 12 million native speakers; it is the majority language in the Czech Republic and spoken by Czechs worldwide. The language was known as Bohemian in English until the late 19th century...

, many Sudeten Germans were employed in the administration of the ethnic Czech

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

as well as in Nazi organizations (Gestapo, etc.). The most notable was Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in Czechoslovakia prior to and during World War II and an SS-Obergruppenführer...

: the SS and Police general and Secretary of State in the Protectorate.

Expulsions and resettlement after World War II

After the end of World War II, the Potsdam ConferencePotsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

in 1945 determined that Sudeten Germans would have to leave Czechoslovakia (see Expulsion of Germans after World War II

Expulsion of Germans after World War II

The later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

). As a consequence of the immense hostility against all Germans that had grown within Czechoslovakia due to Nazi behaviour, the overwhelming majority of Germans were expelled (while the relevant Czechoslovak legislation provided for the remaining Germans who were able to prove their anti-Nazi affiliation). The number of expelled Germans in the early phase (spring-summer 1945) is estimated to be around 500,000 people. The remaining Germans were allowed to stay in Czechoslovakia. Some German refugees from Czechoslovakia are represented by the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft

Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft

The Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft is an organization representing Sudeten German refugees from the Sudetenland. Most of them fled to West Germany from Czechoslovakia during the Expulsion of Germans after World War II....

.

Many of the Germans who stayed in Czechoslovakia later emigrated to West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

(more than 100,000). As the German population was transferred out of the country, the former Sudetenland was resettled, mostly by Czechs but also by other nationalities of Czechoslovakia: Slovaks

Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people, or Slovakians are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia...

, Greeks (arriving in the wake of Greek civil war), Volhynian Czechs

Volhynia

Volhynia, Volynia, or Volyn is a historic region in western Ukraine located between the rivers Prypiat and Southern Bug River, to the north of Galicia and Podolia; the region is named for the former city of Volyn or Velyn, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River, whose name may come...

, Gypsies and Hungarians (though the Hungarians were forced into this and later returned home — see Hungarians in Slovakia: Population exchanges). Some areas — such as part of Czech Silesian-Moravian borderland, southwestern Bohemia (Šumava forest), western and northern parts of Bohemia — remained depopulated for several strategic reasons (extensive mining, military interests etc.) or simply for their lack of attractions. Moreover, prior the building of Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

(by means of engineer equipment) in 1952-55, the so called "forbidden zone" (up to 2 km from border line) and "border zone" (up to 12 km from border line) were established in which no civilian persons (forbidden zone) eventually no disloyal or suspected civilians (border zone) could reside or work. Thus, e.g., the whole Aš-Bulge

Aš

Aš is a town in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic.-History:Previously uninhabited hills and swamps, the town of Asch was founded in the early 11th century by German colonists. Slavic settlements in the area are not known. The dialect spoken in the town was that of the Upper Palatinate,...

fell within the border zone. This status remained until 1989

Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution or Gentle Revolution was a non-violent revolution in Czechoslovakia that took place from November 17 – December 29, 1989...

.

There remained areas with noticeable German minorities in the westernmost borderland around Cheb

Cheb

Cheb is a city in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic, with about 33,000 inhabitants. It is situated on the river Ohře , at the foot of one of the spurs of the Smrčiny and near the border with Germany...

, where skilled forced labour of remaining ethnic German men remained necessary in mining and industry until 1955 ; in the Egerland

Egerland

The Egerland is a historical region in the far north west of Bohemia in the Czech Republic at the border with Germany. It is named after the German name Eger for the city of Cheb and the main river Ohře...

, German minority organizations continue to exist. Also, the small town of Kravaře

Kravare

Kravaře is a town in Silesia in the Czech Republic. It has 6,650 inhabitants. It is located between Ostrava and Opava . It is part of the Hlučínsko micro-region.-History of the town:The first historical record of Kravaře is from 1224...

in the multi-ethnic Hlučín Region

Hlucín Region

Hlučín Area is a part of Czech Silesia in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic, named after the largest town Hlučín. Its area is , in 2001 was inhabited by 73,914 citizens, thus the population density was 233 per km².-History:...

of Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia is an unofficial name of one of the three Czech lands and a section of the Silesian historical region. It is located in the north-east of the Czech Republic, predominantly in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with a section in the northern Olomouc Region...

has an ethnic German majority (2006), including an ethnic German mayor.

In the 2001 census, approximately 40,000 people in the Czech Republic claimed German ethnicity.

See also

- Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918-1938)From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 3 million ethnic Germans were living in what became the Czech lands of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia. Ethnic Germans had lived in Bohemia, a part of the Holy Roman Empire, since the 14th century , mostly in...

- German occupation of CzechoslovakiaGerman occupation of CzechoslovakiaGerman occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

- Expulsion of Germans after World War IIExpulsion of Germans after World War IIThe later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

- Expulsion of Germans from CzechoslovakiaExpulsion of Germans from CzechoslovakiaThe expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and expulsions of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II....

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators in Czechoslovakia

- Sudetendeutsche LandsmannschaftSudetendeutsche LandsmannschaftThe Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft is an organization representing Sudeten German refugees from the Sudetenland. Most of them fled to West Germany from Czechoslovakia during the Expulsion of Germans after World War II....

- Beneš decreesBeneš decreesDecrees of the President of the Republic , more commonly known as the Beneš decrees, were a series of laws that were drafted by the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile in the absence of the Czechoslovak parliament during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in World War II and issued by President...

External links

- Czech-German Declaration

- WW2DB: German Annexation of Sudetenland

- Ethnic cleansing in post World War II Czechoslovakia: the presidential decrees of Edward Benes, 1945-1948 Available as MS WordMicrosoft WordMicrosoft Word is a word processor designed by Microsoft. It was first released in 1983 under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems. Subsequent versions were later written for several other platforms including IBM PCs running DOS , the Apple Macintosh , the AT&T Unix PC , Atari ST , SCO UNIX,...

for Windows file. - Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft

- Sudetendeutsches Archiv

- Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft Bayern

- Ackermann-Gemeinde

- sudetengermans.com

- Bell, P.M.H. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe. Addison WesleyPearson PLCPearson plc is a global media and education company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. It is both the largest education company and the largest book publisher in the world, with consumer imprints including Penguin, Dorling Kindersley and Ladybird...

Longman Ltd: London, 1997. - Westermann, Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte

- WorldStatesmen - Czech Republic; includes description of the 1918 Gaus

- Description of the expulsion, published by the group of expellees, 1951

- BBC 2002 article about Sudeten Germans

- Map