Potsdam Conference

Encyclopedia

Cecilienhof

Schloss Cecilienhof is a palace in the northern part of the Neuer Garten park in Potsdam, Germany, close to the Jungfernsee lake. Since 1990 it is part of the Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin UNESCO World Heritage Site....

, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam

Potsdam

Potsdam is the capital city of the German federal state of Brandenburg and part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. It is situated on the River Havel, southwest of Berlin city centre....

, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The three nations were represented by Communist Party General Secretary

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the title given to the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. With some exceptions, the office was synonymous with leader of the Soviet Union...

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

and later, Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

, and President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

.

Stalin, Churchill, and Truman—as well as Attlee, who participated alongside Churchill while awaiting the outcome of the 1945 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1945

The United Kingdom general election of 1945 was a general election held on 5 July 1945, with polls in some constituencies delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, due to local wakes weeks. The results were counted and declared on 26 July, due in part to the time it took to...

, and then replaced Churchill as Prime Minister after the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

's victory over the Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

—gathered to decide how to administer punishment to the defeated Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, which had agreed to unconditional surrender

Unconditional surrender

Unconditional surrender is a surrender without conditions, in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. In modern times unconditional surrenders most often include guarantees provided by international law. Announcing that only unconditional surrender is acceptable puts psychological...

nine weeks earlier, on 8 May (V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day

Victory in Europe Day commemorates 8 May 1945 , the date when the World War II Allies formally accepted the unconditional surrender of the armed forces of Nazi Germany and the end of Adolf Hitler's Third Reich. The formal surrender of the occupying German forces in the Channel Islands was not...

). The goals of the conference also included the establishment of post-war order, peace treaties issues, and countering the effects of war.

Relationships amongst the leaders

In the five months since the Yalta ConferenceYalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

, a number of changes had taken place which would greatly affect the relationships between the leaders.

1. The Soviet Union was occupying Central and Eastern Europe

By July, the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

effectively controlled the Baltic States, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania, and refugees were fleeing out of these countries fearing a Communist take-over. Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

had set up a Communist government in Poland. Britain and America protested, but Stalin defended his actions. He insisted that his control of Eastern Europe was a defensive measure against possible future attacks and believed that it was a legitimate sphere of Soviet influence.

2. Britain had a new Prime Minister

The results of the British election

United Kingdom general election, 1945

The United Kingdom general election of 1945 was a general election held on 5 July 1945, with polls in some constituencies delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, due to local wakes weeks. The results were counted and declared on 26 July, due in part to the time it took to...

became known during the conference. As a result of the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

victory over the Conservative Party the leadership changed hands. Consequently, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee assumed leadership following Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, whose Soviet policy since the early 1940s had differed considerably from former U.S. President Roosevelt's, with Churchill believing Stalin to be a "devil"-like tyrant leading a vile system.

3. America had a new President, and the war was ending

President Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

died on 12 April 1945, and Vice-President, Harry Truman assumed the presidency; his ascendence saw VE Day within a month and VJ Day on the horizon. During the war and in the name of Allied unity, Roosevelt had brushed off warnings of a potential domination by a Stalin dictatorship in part of Europe. He explained that "I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of a man" and reasoned "I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask for nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace."

While inexperienced in foreign affairs, Truman had closely followed the allied progress of the war. George Lenczowski

George Lenczowski

George Lenczowski was a lawyer, diplomat, scholar, and Professor of Political Science, Emeritus, at the University of California, Berkeley. Lenczowski was a pioneer in his field as the founder and first chair of the Committee of Middle Eastern Studies at Berkeley...

notes "despite the contrast between his relatively modest background and the international glamour of his aristocratic predecessor, [Truman] had the courage and resolution to reverse the policy that appeared to him naive and dangerous", which was "in contrast to the immediate, often ad hoc moves and solutions dictated by the demands of the war.". With the end of the war, the priority of allied unity was replaced with a new challenge, the nature of the relationship between the two emerging superpowers.

Truman became much more suspicious of communist moves than Roosevelt had been, and he became increasingly suspicious of Soviet intentions under Stalin. Truman and his advisers saw Soviet actions in Eastern Europe as aggressive expansionism which was incompatible with the agreements Stalin had committed to at Yalta the previous February. In addition, it was at the Potsdam Conference that Truman became aware of possible complications elsewhere, when Stalin objected to Churchill's proposal for an early allied withdrawal from Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

, ahead of the agreed upon schedule set at the Tehran Conference

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

. However, the Potsdam Conference marks the first and only time Truman would ever meet Stalin in person.

4. The US had tested an atomic bomb

On 16 July 1945, the Americans successfully tested an atomic bomb at the Trinity test at Alamogordo

Alamogordo, New Mexico

Alamogordo is the county seat of Otero County and a city in south-central New Mexico, United States. A desert community lying in the Tularosa Basin, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains. It is the nearest city to Holloman Air Force Base. The population was 35,582 as of the 2000...

in the New Mexico desert, USA. 21 July; Churchill and Truman agreed that the weapon should be used. Truman had previously been encouraged by the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, to inform the Soviets of this new development, in order to avoid sowing distrust over keeping the USSR out of the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

. Truman did not tell Stalin of the weapon until 25 July when he advised Stalin that America had "a new weapon of unusually destructive force." According to various eyewitnesses, Stalin appeared uninterested. It later became known that Stalin was actually aware of the atomic bomb before Truman was, as he had multiple spies that had infiltrated the Manhattan Project from very early on (notably Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

, Ted Hall, and David Greenglass

David Greenglass

David Greenglass was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked in the Manhattan project. He was the brother of Ethel Rosenberg.-Biography:...

), while Truman had only learned about the weapon after Roosevelt's death. By the 26 July, the Potsdam Declaration had been broadcast to Japan, threatening total destruction unless the Imperial Japanese government submitted to unconditional surrender. Joseph Stalin suggested that Truman preside over the conference as the only head of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

attending, a recommendation accepted by Attlee.

Potsdam Agreement

Germany

- See also: Expulsion of Germans after World War IIExpulsion of Germans after World War IIThe later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

, The industrial plans for Germany, Oder-Neisse lineOder-Neisse lineThe Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, former eastern territories of Germany, and German reparations for World War IIGerman reparations for World War IIAfter World War II, both West Germany and East Germany were obliged to pay war reparations to the Allied governments, according to the Potsdam Conference...

- Issuance of a statement of aims of the occupation of Germany by the Allies: demilitarization, denazificationDenazificationDenazification was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of any remnants of the National Socialist ideology. It was carried out specifically by removing those involved from positions of influence and by disbanding or rendering...

, democratizationDemocratizationDemocratization is the transition to a more democratic political regime. It may be the transition from an authoritarian regime to a full democracy, a transition from an authoritarian political system to a semi-democracy or transition from a semi-authoritarian political system to a democratic...

, decentralizationDecentralization__FORCETOC__Decentralization or decentralisation is the process of dispersing decision-making governance closer to the people and/or citizens. It includes the dispersal of administration or governance in sectors or areas like engineering, management science, political science, political economy,...

and decartelizationDecartelizationDecartelization is the transition of a national economy from monopoly control by groups of large businesses, known as cartels, to a free market economy...

. - Division of Germany and Austria respectively into four occupation zones (earlier agreed in principle at YaltaYalta ConferenceThe Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

), and the similar division of each capital, Berlin and ViennaViennaVienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, into four zones. - Agreement on the prosecution of NaziNazismNazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

war criminalsNuremberg TrialsThe Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

. - Reversion of all German annexations in Europe, including SudetenlandSudetenlandSudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

, Alsace-LorraineAlsace-LorraineThe Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after it annexed most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east...

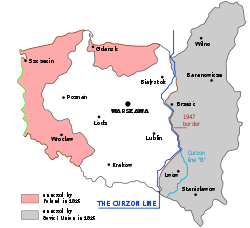

, Austria, and the westernmost parts of PolandPolish areas annexed by Nazi GermanyAt the beginning of World War II, nearly a quarter of the pre-war Polish areas were annexed by Nazi Germany and placed directly under German civil administration, while the rest of Nazi occupied Poland was named as General Government... - Germany's eastern border was to be shifted westwards to the Oder-Neisse lineOder-Neisse lineThe Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, effectively reducing Germany in size by approximately 25% compared to its 1937 borders. The territories east of the new border comprised East PrussiaEast PrussiaEast Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

, SilesiaSilesiaSilesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, West PrussiaWest PrussiaWest Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

, and two thirds of PomeraniaPomeraniaPomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

. These areas were mainly agricultural, with the exception of Upper SilesiaUpper SilesiaUpper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

which was the second largest centre of German heavy industry. - Expulsion of the German populations remaining beyond the new eastern borders of Germany.

- Agreement on war reparationsWar reparationsWar reparations are payments intended to cover damage or injury during a war. Generally, the term war reparations refers to money or goods changing hands, rather than such property transfers as the annexation of land.- History :...

to the Soviet Union from their zone of occupation in Germany. It was also agreed that 10% of the industrial capacity of the western zones unnecessary for the German peace economy should be transferred to the Soviet Union within 2 years. Stalin proposed and it was accepted that Poland was to be excluded from division of German compensation to be later granted 15% of compensation given to Soviet Union. - Ensuring that German standards of living did not exceed the European average. The types and amounts of industry to dismantle to achieve this was to be determined later (see The industrial plans for Germany).

- Destruction of German industrial war-potential through the destruction or control of all industry with military potential. To this end, all civilian shipyardShipyardShipyards and dockyards are places which repair and build ships. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance and basing activities than shipyards, which are sometimes associated more with initial...

s and aircraft factoriesAircraft parts industryThe aircraft parts industry is defined as companies that focus on the aerospace parts market. These include, for example:* list price reference providers * manufacturing...

were to be dismantled or otherwise destroyed. All production capacity associated with war-potential, such as metals, chemical, machinery etc. were to be reduced to a minimum level which was later determined by the Allied Control CommissionAllied CommissionFollowing the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allied Powers were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far Eastern Advisory Commission to make recommendations...

. Manufacturing capacity thus made "surplus" was to be dismantled as reparations or otherwise destroyed. All research and international tradeInternational tradeInternational trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product...

was to be controlled. The economy was to be decentralized (decartelization). The economy was also to be reorganized with primary emphasis on agriculture and peaceful domestic industries. In early 1946 agreement was reached on the details of the latter: Germany was to be converted into an agricultural and light industryLight industryLight industry is usually less capital intensive than heavy industry, and is more consumer-oriented than business-oriented...

economy. German exports were to be coal, beer, toys, textiles, etc. — to take the place of the heavy industrialHeavy industryHeavy industry does not have a single fixed meaning as compared to light industry. It can mean production of products which are either heavy in weight or in the processes leading to their production. In general, it is a popular term used within the name of many Japanese and Korean firms, meaning...

products which formed most of Germany's pre-war exports.

- Issuance of a statement of aims of the occupation of Germany by the Allies: demilitarization, denazification

Poland

- See also: Western betrayalWestern betrayalWestern betrayal, also called Yalta betrayal, refers to a range of critical views concerning the foreign policies of several Western countries between approximately 1919 and 1968 regarding Eastern Europe and Central Europe...

and Territorial changes of Poland after World War IITerritorial changes of Poland after World War IIThe territorial changes of Poland after World War II were very extensive. In 1945, following the Second World War, Poland's borders were redrawn following the decisions made at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 at the insistence of the Soviet Union...

- A Provisional Government of National UnityProvisional Government of National UnityThe Provisional Government of National Unity was a government formed by a decree of the State National Council on 28 June 1945. It was created as a coalition government between Polish Communists and the Polish government-in-exile...

recognized by all three powers should be created (known as the Lublin Poles). Recognition of the Soviet controlled government by the Western Powers effectively meant the end of recognition for the existing Polish government-in-exile (known as the London Poles). - Poles who were serving in the British Army should be free to return to Poland, with no security upon their return to the communist country guaranteed.

- The provisional western border should be the Oder-Neisse lineOder-Neisse lineThe Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, defined by the Oder and Neisse rivers. Parts of East Prussia and the former Free City of DanzigFree City of DanzigThe Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

should be under Polish administration. However the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement (which would take place at the Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to GermanyTreaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to GermanyThe Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany, was negotiated in 1990 between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic , and the Four Powers which occupied Germany at the end of World War II in Europe: France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the...

in 1990) - The Soviet Union declared it will settle the reparation claims of Poland from its own share of the overall reparation payments.

- A Provisional Government of National Unity

Potsdam Declaration

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

, Chairman

President of the Republic of China

The President of the Republic of China is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Republic of China . The Republic of China was founded on January 1, 1912, to govern all of China...

of the Nationalist Government of China

Republic of China

The Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

(the Soviet Union was not at war with Japan) issued the Potsdam Declaration

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender is a statement calling for the Surrender of Japan in World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S...

which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan during World War II in Asia.

Aftermath

Truman had mentioned an unspecified "powerful new weapon" to Stalin during the conference. Towards the end of the conference, Japan was given an ultimatum to surrender (in the name of the United States, Great Britain and China) or meet "prompt and utter destruction", which did not mention the new bomb. After prime minister Kantarō SuzukiKantaro Suzuki

Baron was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, member and final leader of the Taisei Yokusankai and 42nd Prime Minister of Japan from 7 April-17 August 1945.-Early life:...

's reply to maintain silence (mokusatsu

Mokusatsu

is a Japanese word meaning "to ignore" or "to treat with silent contempt". It is composed of two kanji: and . The government of Japan used the term as a response to Allied demands in the Potsdam Declaration for unconditional surrender in World War II, which influenced President Harry S...

, which was misinterpreted as a declaration that the Empire of Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

should ignore the ultimatum), atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively.

In addition to annexing several occupied countries as (or into) Soviet Socialist Republics, other countries were converted into Soviet Satellite

Satellite state

A satellite state is a political term that refers to a country that is formally independent, but under heavy political and economic influence or control by another country...

states within the Eastern Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

, such as the People's Republic of Poland

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, the People's Republic of Hungary

People's Republic of Hungary

The People's Republic of Hungary or Hungarian People's Republic was the official state name of Hungary from 1949 to 1989 during its Communist period under the guidance of the Soviet Union. The state remained in existence until 1989 when opposition forces consolidated in forcing the regime to...

, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 until end of 1989 , a Soviet satellite state of the Eastern Bloc....

, the People's Republic of Romania, the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia the People's Republic of Albania, and later East Germany from the Soviet zone of German occupation.

Previous major conferences

- the Yalta ConferenceYalta ConferenceThe Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

, 4 to 11 February 1945 - the Second Quebec ConferenceSecond Quebec ConferenceThe Second Quebec Conference was a high level military conference held during World War II between the British, Canadian and American governments. The conference was held in Quebec City, September 12, 1944 - September 16, 1944, and was the second conference to be held in Quebec, after "QUADRANT"...

, 12 to 16 September 1944 - the Tehran ConferenceTehran ConferenceThe Tehran Conference was the meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill between November 28 and December 1, 1943, most of which was held at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. It was the first World War II conference amongst the Big Three in which Stalin was present...

, 28 November to 1 December 1943 - the Cairo ConferenceCairo ConferenceThe Cairo Conference of November 22–26, 1943, held in Cairo, Egypt, addressed the Allied position against Japan during World War II and made decisions about postwar Asia...

, 22 to 26 November 1943 - the Casablanca Conference, 14 to 24 January 1943

Further reading

- Michael Beschloss. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945 (2002)

- de Zayas, Alfred M.: A terrible Revenge. Palgrave/Macmillan, New York, 1994. ISBN 1-4039-7308-3.

- de Zayas, Alfred M.: Die deutschen Vertriebenen. Graz, 2006. ISBN 3-902475-15-3.

- de Zayas, Alfred M.: Heimatrecht ist Menschenrecht. München, 2001. ISBN 3-8004-1416-3.

- de Zayas, Alfred M.: Nemesis at Potsdam. London, 1977. ISBN 0-8032-4910-1.

- de Zayas, Alfred M.: 50 Thesen zur Vertreibung. München, 2008. ISBN 978-3-9812110-0-9.

- Farquharson, J. E. "Anglo-American Policy on German Reparations from Yalta to Potsdam." English Historical Review 1997 112(448): 904–926. Issn: 0013-8266 Fulltext: in Jstor

- Gimbel, John. "On the Implementation of the Potsdam Agreement: an Essay on U.S. Postwar German Policy." Political Science Quarterly 1972 87(2): 242–269. Issn: 0032-3195 Fulltext: in Jstor

- Gormly, James L. From Potsdam to the Cold War: Big Three Diplomacy, 1945–1947. Scholarly Resources, 1990. 242 pp.

- Mee, Charles L., Jr. Meeting at Potsdam. M. Evans & Company, 1975. 370 pp.

- Naimark, Norman: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge, Harvard University Pressm 2001.

- Prauser, Steffen and Rees, Arfon: The Expulsion of the "German"nCommunities from Eastern Europe at the Second World War. Florence, Italy, European University Institute, 2004.

- Thackrah, J. R. "Aspects of American and British Policy Towards Poland from the Yalta to the Potsdam Conferences, 1945." Polish Review 1976 21(4): 3–34. Issn: 0032-2970

- Zayas, Alfred M. de. Nemesis at Potsdam: The Anglo-Americans and the Expulsion of the Germans, Background, Execution, Consequences. Routledge, 1977. 268 pp.

- Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers. The Conference of Berlin (Potsdam Conference, 1945) 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960

External links

- Truman and the Potsdam Conference

- Annotated bibliography for the Potsdam Conference from the Alsos Digital Library

- The Potsdam Conference, July – August 1945 on navy.mil

- United States Department of State Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers : the Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference) 1945 Volume I Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945

- United States Department of State Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers : the Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference) 1945 Volume II Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945

- European Advisory Commission, Austria, Germany Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers, 1945.

- Cornerstone of Steel, TimeTime (magazine)Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

magazine, 21 January 1946 - Cost of Defeat, TimeTime (magazine)Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

magazine, 8 April 1946 - Pas de Pagaille! TimeTime (magazine)Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

magazine, 28 July 1947 - Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference

- Interview with James W. Riddleberger Chief, Division of Central European Affairs, U.S. Dept. of State, 1944–47

- "The Myth of Potsdam," in B. Heuser et al., eds., Myths in History (Providence, Rhode Island and Oxford: Berghahn, 1998)

- "The United States, France, and the Question of German Power, 1945–1960," in Stephen Schuker, ed., Deutschland und Frankreich vom Konflikt zur Aussöhnung: Die Gestaltung der westeuropäischen Sicherheit 1914–1963, Schriften des Historischen Kollegs, Kolloquien 46 (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2000).

- U.S. Economic Policy Towards defeated countries April, 1946.

- Lebensraum