Operation Anthropoid

Encyclopedia

Targeted killing

Targeted killing is the deliberate, specific targeting and killing, by a government or its agents, of a supposed terrorist or of a supposed "unlawful combatant" who is not in that government's custody...

of top German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

SS leader Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich , also known as The Hangman, was a high-ranking German Nazi official.He was SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei, chief of the Reich Main Security Office and Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia...

. He was the chief of the Reich Main Security Office

RSHA

The RSHA, or Reichssicherheitshauptamt was an organization subordinate to Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacities as Chef der Deutschen Polizei and Reichsführer-SS...

(Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or RSHA), the acting Protector of Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

, and a chief planner of the Final Solution

Final Solution

The Final Solution was Nazi Germany's plan and execution of the systematic genocide of European Jews during World War II, resulting in the most deadly phase of the Holocaust...

, the Nazi German

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

programme for the genocide

The Holocaust

The Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

of the Jews of Europe.

Reinhard Heydrich

Heydrich was a SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei who had been the chief of the RSHA since September 1939. This was an organisation that included the Secret State Police (GestapoGestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

), the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst, or SD

Sicherheitsdienst

Sicherheitsdienst , full title Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS, or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. The organization was the first Nazi Party intelligence organization to be established and was often considered a "sister organization" with the...

), and the Criminal Police (Kripo). In August 1940, Heydrich became the President of the International Criminal Police Organisation (Interpol

Interpol

Interpol, whose full name is the International Criminal Police Organization – INTERPOL, is an organization facilitating international police cooperation...

). Heydrich was a key planner in eliminating Hitler’s opponents, as well as (later) the key planner of the genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

of the Jews. He was involved in most of Hitler’s intrigues and a valued political ally, adviser and friend of the dictator

Dictator

A dictator is a ruler who assumes sole and absolute power but without hereditary ascension such as an absolute monarch. When other states call the head of state of a particular state a dictator, that state is called a dictatorship...

.

In September 1941, Heydrich was appointed acting Protector of Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

, replacing Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath was a German diplomat remembered mostly for having served as Foreign minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938...

. Hitler agreed with Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

and Heydrich that von Neurath's "soft approach" to the Czechs promoted anti-German sentiment, and encouraged anti-German resistance by strikes and sabotage. Heydrich came to Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

to "strengthen policy, carry out counter measures against resistance" and keep up production quotas of Czech motor and arms that were "extremely important to the German war effort". During his role as de facto dictator of Bohemia and Moravia, Heydrich often drove with his chauffeur

Chauffeur

A chauffeur is a person employed to drive a passenger motor vehicle, especially a luxury vehicle such as a large sedan or limousine.Originally such drivers were always personal servants of the vehicle owner, but now in many cases specialist chauffeur service companies, or individual drivers provide...

in a car with an open roof. This was a show of his confidence in the occupation forces and in the effectiveness of his government. Due to his brutal efficiency, Heydrich was nicknamed the Butcher of Prague, the Blond Beast, and the Hangman.

Strategic context

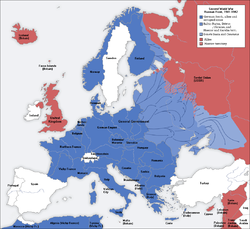

Continental Europe

Continental Europe, also referred to as mainland Europe or simply the Continent, is the continent of Europe, explicitly excluding European islands....

, and German forces were approaching Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

. The Allies deemed Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

capitulation

Capitulation (surrender)

Capitulation , an agreement in time of war for the surrender to a hostile armed force of a particular body of troops, a town or a territory....

likely. The exiled government of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, under President

President

A president is a leader of an organization, company, trade union, university, or country.Etymologically, a president is one who presides, who sits in leadership...

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

, was under pressure from British intelligence, as there had been very little visible resistance since the occupation of the Sudeten

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

regions of the country in 1938 (occupation of the whole country began in 1939). The takeover of these regions that was enforced by the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

and the subsequent terror of the German Reich broke the will of the Czechs

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

for a period.

While in several other countries defeated in open warfare (e.g. Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

and Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

) the resistance was active from the very beginning of occupation, the subdued Czech lands

Czech lands

Czech lands is an auxiliary term used mainly to describe the combination of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia. Today, those three historic provinces compose the Czech Republic. The Czech lands had been settled by the Celts , then later by various Germanic tribes until the beginning of 7th...

remained relatively calm, simultaneously producing significant amounts of military material

Materiel

Materiel is a term used in English to refer to the equipment and supplies in military and commercial supply chain management....

for the Third Reich. The exiled government felt it had to do something that would inspire the Czechs, as well as show the world the Czechs were allies.

The status of Reinhard Heydrich as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia as well as his reputation for terrorizing local citizens led to him being chosen over Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in Czechoslovakia prior to and during World War II and an SS-Obergruppenführer...

as an assassination

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

target. The operation was also meant to prove to the Nazis that they were not untouchable.

Planning

The operation was given the codename "Anthropoid". With the British Special Operations ExecutiveSpecial Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive was a World War II organisation of the United Kingdom. It was officially formed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton on 22 July 1940, to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Axis powers and to instruct and aid local...

(SOE), preparation began on October 20, 1941. Warrant Officer

Warrant Officer

A warrant officer is an officer in a military organization who is designated an officer by a warrant, as distinguished from a commissioned officer who is designated an officer by a commission, or from non-commissioned officer who is designated an officer by virtue of seniority.The rank was first...

Jozef Gabčík

Jozef Gabcík

Jozef Gabčík was a Slovak soldier of Czechoslovak army involved in Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich....

and Staff Sergeant

Staff Sergeant

Staff sergeant is a rank of non-commissioned officer used in several countries.The origin of the name is that they were part of the staff of a British army regiment and paid at that level rather than as a member of a battalion or company.-Australia:...

Karel Svoboda were chosen to carry out the operation on October 28, 1941 (Czechoslovakia's Independence Day). Svoboda was replaced with Jan Kubiš

Jan Kubiš

Jan Kubiš was a Czech soldier, one of a team of Czechoslovak British-trained soldiers sent to assassinate acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, in 1942 as part of Operation Anthropoid.- Biography :Jan Kubiš was born in 1913 in Dolní Vilémovice,...

after a head injury during training, causing delays in the mission, as Kubiš had not completed training nor had the necessary false documents been prepared for him.

Insertion

Jozef Gabcík

Jozef Gabčík was a Slovak soldier of Czechoslovak army involved in Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich....

and Jan Kubiš were airlifted along with seven soldiers from Czechoslovakia’s army-in-exile in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and two other groups named Silver A and Silver B (who had different missions) by a Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

Halifax

Handley Page Halifax

The Handley Page Halifax was one of the British front-line, four-engined heavy bombers of the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. A contemporary of the famous Avro Lancaster, the Halifax remained in service until the end of the war, performing a variety of duties in addition to bombing...

of No. 138 Squadron into Czechoslovakia at 10pm on December 28, 1941. Gabčík and Kubiš landed near Nehvizdy

Nehvizdy

Nehvizdy is a market town in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It is located in a flat agricultural landscape about 22 km east of Prague on road connecting the capital city with Poděbrady and Hradec Králové...

east of Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

; although the plan was to land near Pilsen, the pilots had problems with orientation. The soldiers then moved to Pilsen to contact their allies, and from there on to Prague, where the attack was planned.

In Prague, they contacted several families and anti-Nazi organisations who helped them during the preparations for the targeted kill. Gabčík and Kubiš initially planned to kill Heydrich on a train, but after examination of the logistics, they realised that this was not possible. The second plan was to kill him on the road in the forest on the way from Heydrich’s seat to Prague. They planned to pull a cable across the road that would stop Heydrich’s car but, after waiting several hours, their commander, Lt. Adolf Opálka

Adolf Opálka

First Lieutenant Adolf Opálka was a Czechoslovak soldier. He was a member of the Czech sabotage group Out Distance, a World War II anti-Nazi resistance group, and a participant in Operation Anthropoid, the successful mission to kill Reinhard Heydrich.Opálka was born into a middle-class family in...

(from the group Out Distance

Out Distance

Out Distance was a Czech resistance group during World War II, operating in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia .-Operations:At 2AM on 28 March 1942, the group parachuted from a British Halifax plane...

), came to bring them back to Prague. The third plan was to kill Heydrich in Prague.

The attack in Prague

Commuting

Commuting is regular travel between one's place of residence and place of work or full time study. It sometimes refers to any regular or often repeated traveling between locations when not work related.- History :...

from his home in Panenské Břežany

Panenské Břežany

Panenské Břežany is a village and municipality in Prague-East District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic.The municipality covers an area of 5.79 km² and as of 2010 it had a population of 567....

to Prague Castle

Prague Castle

Prague Castle is a castle in Prague where the Kings of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors and presidents of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic have had their offices. The Czech Crown Jewels are kept here...

. Gabčík and Kubiš waited at the tram stop on the curve near Bulovka Hospital in Prague 8

Prague 8

Prague 8 is a municipal district in Prague, Czech Republic.The administrative district of the same name consists of municipal districts Prague 8, Březiněves, Ďáblice and Dolní Chabry.- External links :*...

-Libeň

Liben

Libeň is a Cadastral area and district of Prague. It was connected to Prague in 1901.- People :* Herz Homberg, born here* Ernestine Schumann-Heink, born here* Bohumil Hrabal, lived here...

. Valčik was positioned about 100 metres north of Gabčík and Kubiš as lookout for the approaching car. As Heydrich’s open-topped Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz is a German manufacturer of automobiles, buses, coaches, and trucks. Mercedes-Benz is a division of its parent company, Daimler AG...

neared the pair, Gabčík stepped in front of the vehicle, trying to open fire, but his Sten gun jammed. Heydrich ordered his driver, SS-Oberscharführer

Oberscharführer

Oberscharführer was a Nazi Party paramilitary rank that existed between the years of 1932 and 1945. Translated as “Senior Squad Leader”, Oberscharführer was first used as a rank of the Sturmabteilung and was created due to an expansion of the enlisted positions required by growing SA membership...

Klein, to stop the car. When Heydrich stood up to try to shoot Gabčík, Kubiš threw a modified anti-tank grenade at the vehicle, and its fragments ripped through the car’s right-rear fender, embedding shrapnel and fibres from the upholstery

Upholstery

Upholstery is the work of providing furniture, especially seats, with padding, springs, webbing, and fabric or leather covers. The word upholstery comes from the Middle English word upholder, which referred to a tradesman who held up his goods. The term is equally applicable to domestic,...

into Heydrich’s body, even though the grenade failed to enter the car. Kubiš was also injured by the shrapnel. Heydrich, apparently unaware of his shrapnel injuries, got out of the car, returned fire and tried to chase Gabčík but soon collapsed. Klein returned from his abortive attempt to chase Kubiš, and Heydrich ordered him to chase Gabčík. Klein was shot twice by Gabčík (who was now using his revolver) and wounded in the pursuit. The soldiers were initially convinced that the attack had failed.

Medical treatment and death

Heydrich was taken to Bulovka Hospital, 250 m away. There he was operated on by Professor Hollbaum, a SilesiaSilesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

n German who was chairman of surgery at Charles University in Prague

Charles University in Prague

Charles University in Prague is the oldest and largest university in the Czech Republic. Founded in 1348, it was the first university in Central Europe and is also considered the earliest German university...

, assisted by Dr. W. Dick, the Sudeten German chief of surgery at the hospital. The surgeons reinflated the collapsed left lung, removed the tip of the fractured eleventh rib, sutured the torn diaphragm

Thoracic diaphragm

In the anatomy of mammals, the thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm , is a sheet of internal skeletal muscle that extends across the bottom of the rib cage. The diaphragm separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity and performs an important function in respiration...

, inserted several catheter

Catheter

In medicine, a catheter is a tube that can be inserted into a body cavity, duct, or vessel. Catheters thereby allow drainage, administration of fluids or gases, or access by surgical instruments. The process of inserting a catheter is catheterization...

s and removed the spleen

Spleen

The spleen is an organ found in virtually all vertebrate animals with important roles in regard to red blood cells and the immune system. In humans, it is located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. It removes old red blood cells and holds a reserve of blood in case of hemorrhagic shock...

, which contained a grenade fragment and upholstery material. The surgery lasted an hour and went uneventfully. Heydrich’s direct superior, Reichsführer-SS

Reichsführer-SS

was a special SS rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945. Reichsführer-SS was a title from 1925 to 1933 and, after 1934, the highest rank of the German Schutzstaffel .-Definition:...

Heinrich Himmler, sent his personal physician, Karl Gebhardt

Karl Gebhardt

Karl Gebhardt was a German medical doctor; personal physician of Heinrich Himmler; and one of the main coordinators and perpetrators of surgical experiments performed on inmates of the concentration camps at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz.-Career in the Third Reich:Gebhardt's Nazi career began with his...

, who arrived that evening. After May 29, Heydrich was entirely in the care of SS physicians. Postoperative care included administration of large amounts of morphine

Morphine

Morphine is a potent opiate analgesic medication and is considered to be the prototypical opioid. It was first isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner, first distributed by same in 1817, and first commercially sold by Merck in 1827, which at the time was a single small chemists' shop. It was more...

. There are contradictory accounts concerning whether sulfanilamides

Sulfonamide (medicine)

Sulfonamide or sulphonamide is the basis of several groups of drugs. The original antibacterial sulfonamides are synthetic antimicrobial agents that contain the sulfonamide group. Some sulfonamides are also devoid of antibacterial activity, e.g., the anticonvulsant sultiame...

were given, but Gebhardt testified at his 1947 war crimes trial that they were not. The patient developed a fever of 38-39 °C and wound drainage. After seven days, his condition appeared to be improving when, while sitting up eating a noon meal, he collapsed and went into shock, dying the next morning. Himmler’s physicians officially described the cause of death as septicaemia, meaning infection of the bloodstream. One of the theories was that some of the horsehair used in the upholstery of Heydrich’s car was forced into his body by the blast of the grenade, causing a systemic infection. It has also been suggested that he died of a cerebral or pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism is a blockage of the main artery of the lung or one of its branches by a substance that has travelled from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream . Usually this is due to embolism of a thrombus from the deep veins in the legs, a process termed venous thromboembolism...

.

Botulinum poisoning theory

The authors of A Higher Form of Killing claim that Heydrich died from botulismBotulism

Botulism also known as botulinus intoxication is a rare but serious paralytic illness caused by botulinum toxin which is metabolic waste produced under anaerobic conditions by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and affecting a wide range of mammals, birds and fish...

; i.e. botulinum poisoning. According to this theory, the Type 73 hand anti-armour grenade which was used in the attack, had been modified to contain botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin is a protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and is considered the most powerful neurotoxin ever discovered. Botulinum toxin causes Botulism poisoning, a serious and life-threatening illness in humans and animals...

. This story originates from comments made by Paul Fildes

Paul Fildes

Sir Paul Gordon Fildes OBE FRS was a British pathologist and microbiologist who worked at Porton Down during the Second World War....

, a Porton Down

Porton Down

Porton Down is a United Kingdom government and military science park. It is situated slightly northeast of Porton near Salisbury in Wiltshire, England. To the northwest lies the MoD Boscombe Down test range facility which is operated by QinetiQ...

botulism researcher. However, there is only circumstantial evidence to support this allegation (the records of the SOE

Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive was a World War II organisation of the United Kingdom. It was officially formed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton on 22 July 1940, to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Axis powers and to instruct and aid local...

for the period have remained sealed). This allegation remains unverified, as Fildes' comments are merely hearsay and few medical records of Heydrich's collapse have been preserved.

The general evidence cited to support the theory includes the curious modifications made to the Type 73 grenade: the upper third part of this British anti-tank grenade had been removed and the open end and sides wrapped up with tape. A specially modified weapon could be explained by the need to attach a toxic or biological payload. In addition, Heydrich received excellent medical care by the standards of the time. His autopsy showed none of the usual signs of septicaemia, although infection of the wound and areas surrounding the lungs and heart was reported. The authors of a German wartime report on the incident stated that "Death occurred as a consequence of lesions in the vital parenchymatous organs caused by bacteria and possibly by poisons carried into them by bomb splinters...".

Heydrich's progression to death was not recorded in detail, but he appears to have died due to cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest, is the cessation of normal circulation of the blood due to failure of the heart to contract effectively...

, rather than from respiratory failure

Respiratory failure

The term respiratory failure, in medicine, is used to describe inadequate gas exchange by the respiratory system, with the result that arterial oxygen and/or carbon dioxide levels cannot be maintained within their normal ranges. A drop in blood oxygenation is known as hypoxemia; a rise in arterial...

as is typical with botulinum poisoning. Also, it is worth noting that two other people were wounded by fragments of the same grenade: Kubiš, the Czech soldier who threw the grenade, and a bystander. Neither Heydrich nor these two others are recorded to have displayed any of the usual paralytic or other symptoms associated with botulism. Given that Fildes is reported to have had a tendency to make "extravagant boasts", and that the grenade modifications could have been simply aimed at making it lighter, the validity of the botulinum toxin theory has been questioned.

Reprisals

Hitler ordered the SS and GestapoGestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

to “wade in blood” throughout Bohemia to find Heydrich’s killers. Hitler wanted to start with brutal, widespread killing of the Czech people but, after consultation, he reduced his directive to only several thousand. The Czech lands were an important industrial zone for the German military and indiscriminate killing could reduce the productivity of the region.

More than 13,000 people were ultimately arrested, including the girlfriend of Jan Kubiš, Anna Malinová, who died at Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

Mauthausen Concentration Camp grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly east of the city of Linz.Initially a single camp at Mauthausen, it expanded over time and by the summer of 1940, the...

. First Lieutenant Adolf Opálka's aunt, Marie Opálková, was executed in Mauthausen on 24 October 1942. His father, Viktor Jarolím, was also killed.

Lidice

The most notorious incident was in the village of LidiceLidice

Lidice is a village in the Czech Republic just northwest of Prague. It is built on the site of a previous village of the same name which, as part of the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, was on orders from Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, completely destroyed by German forces in reprisal...

, which was destroyed on June 9, 1942: 199 men were executed, 95 children taken, 8 of whom were taken for adoption by German families, and 195 women

The possibility that the Germans would apply the principle of "collective responsibility

Sippenhaft

Sippenhaft or Sippenhaftung was a form of collective punishment practised in Nazi Germany towards the end of the Second World War. It was a legalized practice in which relatives of persons accused of crimes against the state were held to share the responsibility for those crimes and subject to...

" on this scale in avenging Heydrich's assassination was either not foreseen by the Czech government-in-exile or else was deemed an acceptable cost to pay for eliminating Heydrich and provoking reprisals that would reduce Czech acquiescence to the German administration.

Britain’s wartime leader Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, infuriated, suggested leveling three German villages for every Czech village the Nazis destroyed. Two years after Heydrich's death they planned one more attempt, this time targeting Hitler in Operation Foxley

Operation Foxley

Operation Foxley was a 1944 plan to assassinate Adolf Hitler, made by the British Special Operations Executive . Although detailed preparations were made, no attempt was made to carry out the plan...

, but failed to obtain approval. Operation Anthropoid remains the only targeted killing of a top-ranking Nazi, although the Polish underground killed two senior SS officers in the General government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

(see Operation Kutschera

Operation Kutschera

Operation Kutschera was the code name for the successful assassination of Franz Kutschera, SS and Reich's Police Chief in Warsaw, executed on 1 February 1944 by the Polish Resistance fighters of Home Army's Anti-Gestapo unit Agat...

and Operation Bürkl

Operation Bürkl

Operation Bürkl , or the special combat action Bürkl , was an operation by the Polish resistance conducted on September 7, 1943...

) and General-Kommissar

Commissioner

Commissioner is in principle the title given to a member of a commission or to an individual who has been given a commission ....

of Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

Wilhelm Kube

Wilhelm Kube

Wilhelm Kube was a German politician and Nazi official. He was an important figure in the German Christian movement during the early years of Nazi rule. During the war he became a senior official in the occupying government of the Soviet Union, achieving the rank of Generalkommissar for...

was killed by a Belarusian woman.

Attempted capture of the soldiers

Karel Curda

Karel Čurda was a Czech World War II soldier from the Czechoslovak army in exile. He was parachuted into the protectorate in 1941 as a member of the sabotage group Out Distance...

of the "Out Distance

Out Distance

Out Distance was a Czech resistance group during World War II, operating in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia .-Operations:At 2AM on 28 March 1942, the group parachuted from a British Halifax plane...

" sabotage group was arrested by the Gestapo and gave the names of the team’s local contacts for the bounty

Bounty (reward)

A bounty is a payment or reward often offered by a group as an incentive for the accomplishment of a task by someone usually not associated with the group. Bounties are most commonly issued for the capture or retrieval of a person or object. They are typically in the form of money...

of 0.5 million Reichsmarks

German reichsmark

The Reichsmark was the currency in Germany from 1924 until June 20, 1948. The Reichsmark was subdivided into 100 Reichspfennig.-History:...

.

Čurda betrayed several safe houses provided by the Jindra group, including that of the Moravec family in Žižkov

Žižkov

Žižkov is a cadastral district of Prague, Czech Republic. Most of Žižkov lies in the municipal and administrative district of Prague 3, except for very small parts which are in Prague 8 and Prague 10. Prior to 1922, Žižkov was an independent city....

. At 5.00 am on June 17, the Moravec flat was raided. The family was made to stand in the corridor while the Gestapo searched their flat. Mrs. Moravec was allowed to go to the toilet, and killed herself with a cyanide capsule

Cyanide

A cyanide is a chemical compound that contains the cyano group, -C≡N, which consists of a carbon atom triple-bonded to a nitrogen atom. Cyanides most commonly refer to salts of the anion CN−. Most cyanides are highly toxic....

. Mr. Moravec, oblivious to his family's involvement with the resistance, was taken to the Peček Palác together with his son Ata. Ata was tortured throughout the day. Finally, he was stupefied with brandy and shown his mother's severed head in a fish tank. Ata Moravec told the Gestapo what they wanted to know.

SS troops laid siege to the church but, despite the best efforts of over 700 German soldiers, they were unable to take the paratroopers alive; three, including Kubiš, were killed in the prayer loft (Kubiš was said to have survived the battle, but died shortly afterward from his injuries) after a 2-hour gun battle. The other four, including Gabčík, committed suicide in the crypt

Crypt

In architecture, a crypt is a stone chamber or vault beneath the floor of a burial vault possibly containing sarcophagi, coffins or relics....

after fending off SS attacks, attempts to smoke them out, and fire trucks being brought in to try to flood the crypt. The Germans (SS and police) also had casualties, allegedly 14 SS killed and 21 wounded. The official SS report about the fight mentions five wounded SS soldiers. The men in the church had small calibre pistols, while the attackers had submachine guns, machine guns and hand grenade

Hand grenade

A hand grenade is any small bomb that can be thrown by hand. Hand grenades are classified into three categories, explosive grenades, chemical and gas grenades. Explosive grenades are the most commonly used in modern warfare, and are designed to detonate after impact or after a set amount of time...

s.

Bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

Gorazd

Gorazd (Pavlik) of Prague

Bishop Gorazd of Prague, given name Matěj Pavlík , was the hierarch of the revived Orthodox Church in Moravia, the Church of Czechoslovakia, after World War I...

, in an attempt to minimize the reprisals among his flock, took the blame for the actions in the church on himself, even writing letters to the Nazi authorities. On June 27, 1942, he was arrested and tortured. On September 4, 1942, he, the church's priests, and senior lay leaders were executed by firing squad. (For his actions, Bishop Gorazd was later glorified

Glorification

-Catholicism:For the process by which the Roman Catholic Church or Anglican Communion grants official recognition to someone as a saint, see canonization.-Eastern Orthodox Church:...

as a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

by the Eastern Orthodox Church

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

).

Political consequence and aftermath

The success of the operation made Great Britain and FranceFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

renounce the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

. They agreed that after the Nazis were defeated the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

would be restored to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. It also led to sympathy for the idea of expelling the German population of Czechoslovakia.

As Heydrich was one of the most important Nazi leaders, two large funeral ceremonies were conducted. One was in Prague, where the way to Prague Castle was lined by thousands of SS-men with torches. The second was in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

attended by all leading Nazi figures, including Hitler who placed the German Order

German Order (decoration)

The German Order was the most important award that the Nazi Party could bestow on an individual for "duties of the highest order to the state and party". This award was first made by Adolf Hitler posthumously to Reichsminister Fritz Todt at his funeral in February, 1942...

and Blood Order

Blood Order

The Blood Order , officially known as the Decoration of 9 November 1923 , was one of the most prestigious decorations in the Nazi Party...

medals on the funeral pillow.

Karel Čurda, after attempting suicide, was hanged in 1947 for high treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

.

Memorials

The Slovak National MuseumSlovak National Museum

The Slovak National Museum is the most important institution focusing on scientific research and cultural education in the field of museological activity in Slovakia...

opened an exhibition in May, 2007 to commemorate the heroes of the Czech and Slovak resistance, presenting one of the most important resistance actions in the whole of German-occupied Europe. There is a small fountain

Fountain

A fountain is a piece of architecture which pours water into a basin or jets it into the air either to supply drinking water or for decorative or dramatic effect....

in the Jephson Gardens

The Jephson Gardens

The Jephson Gardens are formal gardens, together with a grassed park, in the town of Leamington Spa, Warwickshire. The gardens, once a place for the wealthy to 'take the air' and 'be seen', are found in the centre of the town with the River Leam flowing to the south of them. One of the town's most...

, Leamington Spa

Leamington Spa

Royal Leamington Spa, commonly known as Leamington Spa or Leamington or Leam to locals, is a spa town in central Warwickshire, England. Formerly known as Leamington Priors, its expansion began following the popularisation of the medicinal qualities of its water by Dr Kerr in 1784, and by Dr Lambe...

(one of the places where the Czech Free Army were based) commemorating the bravery of the troops.