Katyn massacre

Encyclopedia

Democide

Democide is a term revived and redefined by the political scientist R. J. Rummel as "the murder of any person or people by a government, including genocide, politicide, and mass murder." Rummel created the term as an extended concept to include forms of government murder that are not covered by the...

of Polish nationals carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

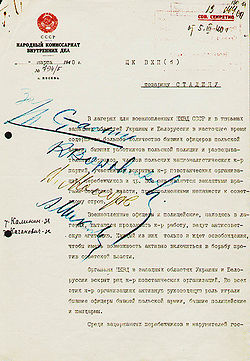

), the Soviet secret police, in April and May 1940. The massacre was prompted by Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was a Georgian Soviet politician and state security administrator, chief of the Soviet security and secret police apparatus under Joseph Stalin during World War II, and Deputy Premier in the postwar years ....

's proposal to execute all members of the Polish Officer Corps, dated 5 March 1940. This official document was approved and signed by the Soviet Politburo

Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Politburo , known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966, functioned as the central policymaking and governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.-Duties and responsibilities:The...

, including its leader, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

. The number of victims is estimated at about 22,000, with 21,768 being a lower bound. The victims were murdered in the Katyn Forest in Russia, the Kalinin

Tver

Tver is a city and the administrative center of Tver Oblast, Russia. Population: 403,726 ; 408,903 ;...

and Kharkiv

Kharkiv

Kharkiv or Kharkov is the second-largest city in Ukraine.The city was founded in 1654 and was a major centre of Ukrainian culture in the Russian Empire. Kharkiv became the first city in Ukraine where the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed in December 1917 and Soviet government was...

prisons and elsewhere. Of the total killed, about 8,000 were officers taken prisoner during the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland (1939)

The 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland was a Soviet military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939, during the early stages of World War II. Sixteen days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, the Soviet Union did so from the east...

, another 6,000 were police officers, with the rest being Polish intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

arrested for allegedly being "intelligence agents, gendarmes

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

, landowners, saboteurs, factory owners, lawyers, officials and priests."

The term "Katyn massacre" originally referred specifically to the massacre at Katyn Forest, near the villages of Katyn and Gnezdovo

Gnezdovo

Gnezdovo or Gnyozdovo is an archeological site located near the village of Gnyozdovo in Smolensk Oblast, Russia. The site contains extensive remains of a Slavic-Varangian settlement that flourished in the 10th century as a major trade station on the trade route from the Varangians to the...

(approximately 19 kilometers/12 miles west of Smolensk

Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River. Situated west-southwest of Moscow, this walled city was destroyed several times throughout its long history since it was on the invasion routes of both Napoleon and Hitler. Today, Smolensk...

, Russia), of Polish military officers in the Kozelsk

Kozelsk

Kozelsk is a town in Kaluga Oblast, Russia, located on the Zhizdra River , southwest of Kaluga. Population: -History:The town of Kozelsk was first mentioned in a chronicle under the year of 1146 as a part of Principality of Chernigov...

prisoner-of-war camp. This was the largest of several simultaneous executions of prisoners of war. Other executions occurred at the geographically distant Starobelsk

Starobilsk

Starobilsk is a town near Luhansk in Ukraine. The settlement has been known since 1686. The city status was given in 1938. Population is 22,040 ....

and Ostashkov

Ostashkov

Ostashkov is a town and the administrative center of Ostashkovsky District of Tver Oblast, Russia, located west of Tver on a peninsula at the southern shore of Lake Seliger. Population:...

camps, at the NKVD headquarters in Smolensk, and at prisons in Kalinin (Tver), Kharkiv, Moscow, and other Soviet cities. Other executions took place at various locations in Belarus and Western Ukraine, based on special lists of Polish prisoners, prepared by the NKVD specifically for those regions. The modern Polish investigation of the killings covered not only the massacre at Katyn forest, but also the other mass murders mentioned above. Polish organisations, such as the Katyn Committee and the Federation of Katyn Families, consider the victims murdered at the locations other than Katyn as part of the overall massacre.

The government of Nazi Germany announced the discovery of mass graves in the Katyn Forest in 1943. The revelation led to the end of diplomatic relations between Moscow and the London-based Polish government-in-exile. The Soviet Union continued to deny responsibility for the massacres until 1990, when it officially acknowledged and condemned the perpetration of the killings by the NKVD.

An investigation conducted by the Prosecutor General's

Prosecutor General of Russia

The Prosecutor General of Russia heads the system of official prosecution in courts known as the Office of the Prosecutor General of Russian Federation ....

Office of the Soviet Union (1990–1991) and the Russian Federation (1991–2004), has confirmed Soviet responsibility for the massacres. It was able to confirm the deaths of 1,803 Polish citizens but refused to classify this action as a war crime or an act of genocide. The investigation was closed on grounds that the perpetrators of the massacre were already dead, and since the Russian government would not classify the dead as victims of Stalinist repression, formal posthumous rehabilitation

Rehabilitation (Soviet)

Rehabilitation in the context of the former Soviet Union, and the Post-Soviet states, was the restoration of a person who was criminally prosecuted without due basis, to the state of acquittal...

was ruled out. The human rights society Memorial

Memorial (society)

Memorial is an international historical and civil rights society that operates in a number of post-Soviet states. It focuses on recording and publicising the Soviet Union's totalitarian past, but also monitors human rights in post-Soviet states....

issued a statement which declared "this termination of investigation is inadmissible" and that their confirmation of only 1,803 people killed "requires explanation because it is common knowledge that more than 14,500 prisoners were killed." In November 2010, the Russian State Duma

State Duma

The State Duma , common abbreviation: Госду́ма ) in the Russian Federation is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia , the upper house being the Federation Council of Russia. The Duma headquarters is located in central Moscow, a few steps from Manege Square. Its members are referred to...

approved a declaration blaming Stalin and other Soviet officials for having personally ordered the massacre.

Background

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

. Meanwhile, Britain and France, obligated by the Polish-British Common Defence Pact

Polish-British Common Defence Pact

The Anglo-Polish military alliance refers to agreements reached between the United Kingdom and the Polish Second Republic for mutual assistance in case of military invasion by "a European Power". According to the secret protocol added to the treaty the phrase "a European Power" used in the...

and Franco-Polish Military Alliance

Franco-Polish Military Alliance

The Franco-Polish alliance was the military alliance between Poland and France that was active between 1921 and 1940.-Background:Already during the France-Habsburg rivalry that started in the 16th century, France had tried to find allies to the east of Austria, namely hoping to ally with Poland...

to attack Germany in the case of such an invasion, demanded that Germany withdraw. On 3 September 1939, after it failed to do so, France, Britain, and most countries of the British Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

declared war on Germany but provided little military support to Poland. They took little other significant military action during what became known as the Phoney War.

The Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

began its own invasion

Soviet invasion of Poland (1939)

The 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland was a Soviet military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939, during the early stages of World War II. Sixteen days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, the Soviet Union did so from the east...

on 17 September, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

. The Red Army advanced quickly and met little resistance, as Polish forces facing them were under orders not to engage the Soviets. About 250,000-454,700 Polish soldiers and policemen had become prisoners

Polish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union (after 1939)

As a result of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers became prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. Many of them were executed; over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the Katyn massacre....

and were interned by the Soviet authorities. Some were freed or escaped quickly, while 125,000 were imprisoned in camps run by the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

. Out of those, 42,400 soldiers, mostly of Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnicity serving in the Polish army who lived in the former Polish territories now annexed by the Soviet Union, were released in October. The 43,000 soldiers born in West Poland, then under German control, were transferred to the Germans; in turn the Soviets received 13,575 Polish prisoners from the Germans.

In addition to military and government personnel, other Polish citizens suffered from repressions. Thousands of members of the Polish intelligentsia were also arrested and imprisoned for allegedly being "intelligence agents, gendarmes

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

, landowners, saboteurs, factory owners, lawyers, officials and priests." Since Poland's conscription system required every nonexempt university graduate to become a military reserve officer, the NKVD was able to round up a significant portion of the Polish educated class. According to estimates by Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance — Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation is a Polish government-affiliated research institute with lustration prerogatives and prosecution powers founded by specific legislation. It specialises in the legal and historical sciences and...

(IPN), roughly 320,000 Polish citizens were deported to the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population, often classified as "enemies of workers," deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite...

(this figure is questioned by some other historians, who stand by the older estimate of about 700,000-1,000,000). IPN estimates the number of Polish citizens that died under Soviet rule during World War II at 150,000 (a correction of the older estimates of up to 500,000). Of the one group of 12,000 Poles sent to Dalstroy

Dalstroy

Dalstroy , also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 by the Soviet NKVD in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Chukotka region of the Russian Far East, now known as Kolyma. Initially it was established as State Trust for Road and...

camp (near Kolyma

Kolyma

The Kolyma region is located in the far north-eastern area of Russia in what is commonly known as Siberia but is actually part of the Russian Far East. It is bounded by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Sea of Okhotsk to the south...

) in 1940-1941, most POWs, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East

Polish Armed Forces in the East

Polish Armed Forces in the East refers to military units composed of Poles created in the Soviet Union at the time when the territory of Poland was occupied by both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the Second World War....

. According to Tadeusz Piotrowski, "...during the war and after 1944, 570,387 Polish citizens had been subjected to some form of Soviet political repression."

As early as September 19, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs and First Rank Commissar of State Security, Lavrentiy Beria, ordered the NKVD to create the Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees to manage Polish prisoners. The NKVD took custody of Polish prisoners from the Red Army, and proceeded to organise a network of reception centers and transit camps and arrange rail transport to prisoner-of-war camps in the western USSR. The largest camps were located at Kozelsk (Optina Monastery

Optina Monastery

The Optina Hermitage is an Eastern Orthodox monastery for men near Kozelsk in Russia. In the 19th century, the Optina was the most important spiritual centre of the Russian Orthodox Church and served as the model for several other monasteries, including the nearby Shamordino Convent...

), Ostashkov (Stolbnyi Island

Stolbnyi Island

Stolobny Island is an island on Lake Seliger in the Tver Oblast of Russia, about 10 km north of the town of Ostashkov.-Nilov Monastery:...

on Seliger Lake near Ostashkov) and Starobelsk. Other camps were at Jukhnovo (rail station "Babynino"), Yuzhe (Talitsy), rail station "Tyotkino" 90 kilometres/56 miles from Putyvl

Putyvl

Putyvl or Putivl is a town in north-east Ukraine, in Sumy Oblast. Currently about 20,000 people live in Putyvl.-History:One of the original Siverian towns, Putyvl was first mentioned as early as 1146 as an important fortress contested between Chernigov and Novgorod-Seversky principalities of...

), Kozelshchyna, Oranki, Vologda

Vologda

Vologda is a city and the administrative, cultural, and scientific center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the Vologda River. The city is a major transport knot of the Northwest of Russia. Vologda is among the Russian cities possessing an especially valuable historical heritage...

(rail station "Zaonikeevo") and Gryazovets

Gryazovets

Gryazovets is a town and the administrative center of Gryazovetsky District of Vologda Oblast, Russia. Municipally, it is incorporated as Gryazovetskoe Urban Settlement in Gryazovetsky Municipal District. Population: -History:...

.

Kozelsk and Starobelsk were used mainly for military officers, while Ostashkov was used mainly for Polish boy scouts, gendarmes, police and prison officers. Some prisoners were members of other groups of Polish intelligentsia, such as priests, landowners and law personnel. The approximate distribution of men throughout the camps was as follows: Kozelsk, 5,000; Ostashkov, 6,570; and Starobelsk, 4,000. They totaled 15,570 men.

According to a report from 19 November 1939, the NKVD had about 40,000 Polish POWs: about 8,000-8,500 officers and warrant officers, 6,000-6,500 police officers and 25,000 soldiers and NCOs who were still being held as POWs. In December, a wave of arrests took into custody some Polish officers who were not yet imprisoned, Ivan Serov

Ivan Serov

State Security General Ivan Aleksandrovich Serov was a prominent leader of Soviet security and intelligence agencies, head of the KGB between March 1954 and December 1958, as well as head of the GRU between 1958 and 1963. He was Deputy Commissar of the NKVD under Lavrentiy Beria, and was to play a...

reported to Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was a Georgian Soviet politician and state security administrator, chief of the Soviet security and secret police apparatus under Joseph Stalin during World War II, and Deputy Premier in the postwar years ....

on 3 December that "in all, 1,057 former officers of the Polish Army had been arrested." The 25,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers were assigned to forced labors

Foreign forced labor in the Soviet Union

Foreign forced labor was used by the Soviet Union during and in the aftermath of the World War II, which continued up to 1950s.There have been two categories of foreigners amassed for forced labor: prisoners of war and civilians...

(road construction, heavy metallurgy).

Once at the camps, from October 1939 to February 1940, the Poles were subjected to lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation by NKVD officers such as Vasily Zarubin

Vasily Zarubin

Vasily Mikhailovich Zarubin Василий Михайлович Зарубин was a Soviet intelligence officer. In the United States, he used the cover name Vasily Zubilin and served as Soviet intelligence Rezident from 1941 to 1944. Zarubin's wife, Elizabeth Zubilin, served with him.Zarubin was born in Moscow...

. The prisoners assumed that they would be released soon, but the interviews were in effect a selection process to determine who would live and who would die. According to NKVD reports, if the prisoners could not be induced to adopt a pro-Soviet attitude, they were declared "hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority."

On 5 March 1940, pursuant to a note to Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

from Beria, four members of the Soviet Politburo

Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Politburo , known as the Presidium from 1952 to 1966, functioned as the central policymaking and governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.-Duties and responsibilities:The...

- Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov , popularly known as Klim Voroshilov was a Soviet military officer, politician, and statesman...

and Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan was an Armenian Old Bolshevik and Soviet statesman during the rules of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev....

- signed an order to execute 25,700 Polish "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries" kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine and Belarus. The reason for the massacre, according to historian Gerhard Weinberg

Gerhard Weinberg

Gerhard Ludwig Weinberg is a German-born American diplomatic and military historian noted for his studies in the history of World War II. Weinberg currently is the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Professor Emeritus of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has been a member of the...

, was that Stalin wanted to deprive a potential future Polish military of a large portion of its talent:

"It has been suggested that the motive for this terrible step [the Katyn massacre] was to reassure the Germans as to the reality of Soviet anti-Polish policy. This explanation is completely unconvincing in view of the care with which the Soviet regime kept the massacre secret from the very German government it was supposed to impress.... A more likely explanation is that... [the massacre] should be seen as looking forward to a future in which there might again be a Poland on the Soviet Union's western border. Since he intended to keep the eastern portion of the country in any case, Stalin could be certain that any revived Poland would be unfriendly. Under those circumstances, depriving it of a large proportion of its military and technical elite would make it weaker."

In addition, Soviets realized that the prisoners constituted a large body of trained and motivated Poles who would not accept a Fourth Partition of Poland.

Executions

Those who died at Katyn included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 3,420 NCOs

Non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer , called a sub-officer in some countries, is a military officer who has not been given a commission...

, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, 131 refugees, 20 university professors, 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists as well as about 200 pilots. In all, the NKVD executed almost half the Polish officer corps. Altogether, during the massacre the NKVD murdered 14 Polish generals: Leon Billewicz

Leon Billewicz

Leon Billewicz was a Polish officer and a General of the Polish Army. Initially serving with the Imperial Russian Army, in November 1918 he joined the Polish forces. In the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1919-1920 he commanded the Polish 13th Infantry Brigade. In 1919 he was promoted to the rank of...

(ret.), Bronisław Bohatyrewicz (ret.), Xawery Czernicki

Xawery Czernicki

Rear Admiral Xawery Stanisław Czernicki was a Polish engineer, military commander and one of the highest ranking officers of the Polish Navy...

(admiral), Stanisław Haller (ret.), Aleksander Kowalewski (ret.), Henryk Minkiewicz

Henryk Minkiewicz

Henryk Minkiewicz was a Polish socialist politician and a General of the Polish Army. Former commander of the Border Defence Corps, he was among the Polish officers murdered in the Katyń massacre.-Early life:...

(ret.), Kazimierz Orlik-Łukoski, Konstanty Plisowski

Konstanty Plisowski

Konstanty Plisowski was a Polish general and military commander. He is known as the commander in the Battles of Jazłowiec and Brześć. He was murdered by the Soviets in the Katyn Massacre.- Biography :...

(ret.), Rudolf Prich

Rudolf Prich

Rudolf Prich was a Polish military officer and a generał dywizji of the Polish Army. He was among the Polish officers murdered by the Soviet Union during the Katyń massacre....

(murdered in Lviv

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

), Franciszek Sikorski (ret.), Leonard Skierski

Leonard Skierski

Leonard Skierski was a Polish military officer and a general of the Imperial Russian Army and then the Polish Army. A veteran of World War I and the Polish-Bolshevik War, he was one of fourteen Polish generals to be murdered by the NKVD in the Katyn massacre of 1940.-Biography:Leonard Skierski was...

(ret.), Piotr Skuratowicz

Piotr Skuratowicz

Piotr Skuratowicz was a Polish military commander and a General of the Polish Army. A renowned cavalryman, he was arrested by the NKVD and murdered in the Katyn massacre....

, Mieczysław Smorawiński and Alojzy Wir-Konas

Alojzy Wir-Konas

Alojzy Wir-Konas was a Polish military commander and a Colonel of the Polish Army. Divisional commander during the Invasion of Poland, he was murdered in the Katyn massacre....

(promoted posthumously). Not all of the executed were ethnic Poles since the Second Polish Republic was a multiethnic state, and its officer corps included Belorusians, Ukrainians, and Jews. It is estimated that about 8% of Katyn massacre victims were Polish Jews. 395 prisoners were spared from the slaughter, among them Stanisław Swianiewicz and Józef Czapski

Józef Czapski

Józef Czapski was a Polish artist, author, and critic, as well as an officer of the Polish Army. As a painter, he is notable for his membership in the Kapist movement, which was heavily influenced by Cézanne...

. They were taken to the Yukhnov camp and then to Gryazovets.

Piatykhatky, Kharkiv

Piatykhatky is a village on the outskirts of Kharkiv, Ukraine.On the territory of a pansionat for workers of the NKVD, children discovered hundreds of buttons of Polish officer uniforms that had risen to the surface. After investigation, a mass burial site was uncovered containing the remains of...

; and police officers from the Ostashkov camp were murdered in the inner NKVD prison of Kalinin (Tver

Tver

Tver is a city and the administrative center of Tver Oblast, Russia. Population: 403,726 ; 408,903 ;...

) and buried in Mednoye

Mednoye

Mednoye is a village in Kalininsky District of Tver Oblast, Russia, located on the Tvertsa River, 28 km west of Tver, by the Moscow–St.Petersburg highway. Population: 3,047 ....

.

Detailed information on the executions in the Kalinin NKVD prison was given during a hearing by Dmitrii Tokarev, former head of the Board of the District NKVD in Kalinin. According to Tokarev, the shooting started in the evening and ended at dawn. The first transport on 4 April 1940, carried 390 people, and the executioners had a hard time killing so many people during one night. The following transports were no greater than 250 people. The executions were usually performed with German-made 7.65 mm Walther PPK

Walther PPK

The Walther PP series pistols are blowback-operated semi-automatic pistols.They feature an exposed hammer, a double-action trigger mechanism, a single-column magazine, and a fixed barrel which also acts as the guide rod for the recoil spring...

pistols supplied by Moscow, but 7.62x38R Nagant M1895

Nagant M1895

The Nagant M1895 Revolver is a seven-shot, gas-seal revolver designed and produced by Belgian industrialist Léon Nagant for the Russian Empire. The Nagant M1895 was chambered for a proprietary cartridge, 7.62x38R, and featured an unusual "gas-seal" system in which the cylinder moved forward when...

revolvers were also used. The executioners used German weapons rather than the standard Soviet revolvers, as the latter were said to offer too much recoil, which made shooting painful after the first dozen of executions. Vasili Mikhailovich Blokhin

Vasili Blokhin

Vasili Mikhailovich Blokhin was a Soviet Major-General who served as the chief executioner of the Stalinist NKVD under the administrations of Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Yezhov and Lavrenty Beria...

, chief executioner

Executioner

A judicial executioner is a person who carries out a death sentence ordered by the state or other legal authority, which was known in feudal terminology as high justice.-Scope and job:...

for the NKVD—and quite possibly the most prolific executioner in history—is reported to have personally shot and killed 7,000 of the condemned, some as young as 18, from the Ostashkov camp at Kalinin prison over a period of 28 days in April 1940.

The killings were methodical. After the personal information of the condemned was checked, he was handcuffed and led to a cell insulated with stacks of sandbags along the walls and a felt-lined, heavy door. The victim was told to kneel in the middle of the cell, was then approached from behind by the executioner and immediately shot in the back of the head. The body was carried out through the opposite door and laid in one of the five or six waiting trucks, whereupon the next condemned was taken inside. In addition to muffling by the rough insulation in the execution cell, the pistol gunshots were also masked by the operation of loud machines (perhaps fans) throughout the night. This procedure went on every night, except for the May Day

May Day

May Day on May 1 is an ancient northern hemisphere spring festival and usually a public holiday; it is also a traditional spring holiday in many cultures....

holiday.

Some 3,000 to 4,000 Polish inmates of Ukrainian prisons and those from Belarus prisons were probably buried in Bykivnia

Bykivnia

Bykivnia is a former small village on the outskirts of Kiev, Ukraine, that was incorporated into the city in 1923. It is known for the National Historic-Memorial Reserve "Bykivnia Graves"....

and in Kurapaty

Kurapaty

Kurapaty is a wooded area on the outskirts of Minsk, Belarus, in which a vast number of people were executed between 1937 and 1941 by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD.The exact count of victims is uncertain, NKVD archives are classified in Belarus...

respectively. Porucznik Janina Lewandowska, daughter of Gen. Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki

Józef Dowbor-Musnicki

Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki was a Polish military officer and commander, serving with the Imperial Russian and then Polish armies...

, was the only woman executed during the massacre at Katyn.

Discovery

The fate of the Polish prisoners was raised soon after the Axis invasion of the Soviet UnionOperation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

in June 1941. The Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet government signed the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

The Sikorski–Mayski Agreement was a treaty between the Soviet Union and Poland signed in London on 30 July 1941. Its name was coined after the two most notable signatories: Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Mayski.- Details :After signing...

which announced the willingness of both to fight together against Nazi Germany and for a Polish army to be formed on Soviet territory. The Polish general Władysław Anders began organizing this army, and soon he requested information about the Polish officers who were missing. During a personal meeting, Stalin assured him and Władysław Sikorski, the Polish Prime Minister, that all the Poles were freed, and that not all could be accounted because the Soviets "lost track" of them in Manchuria

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

.

In 1942 Polish railroad workers heard from the locals about a mass grave of Polish soldiers at Kozielsk near Katyn, found one of the graves and reported it to the Polish Secret State

Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State is a collective term for the World War II underground resistance organizations in Poland, both military and civilian, that remained loyal to the Polish Government in Exile in London. The first elements of the Underground State were put in place in the final days of the...

. The discovery was not seen as important, as nobody thought that the discovered grave could contain so many victims. In early 1943, Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff

Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff

Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff was a military officer in Germany’s Weimar-period Reichswehr and Nazi-period Wehrmacht. He attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler by suicide bombing in March 1943; the plan failed but he was undetected. In April 1943 he discovered the mass graves of the...

, a German officer serving as the intelligence liaison between Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

's Army Group Center and Abwehr

Abwehr

The Abwehr was a German military intelligence organisation from 1921 to 1944. The term Abwehr was used as a concession to Allied demands that Germany's post-World War I intelligence activities be for "defensive" purposes only...

, received reports about mass graves of Polish military officers in the forest on Goat Hill near Katyn, and passed them up to his superiors (sources vary on when exactly did Germans became aware of the graves — from "late 1942" to January/February 1943, and when did the German top decision makers in Berlin received those reports (as early as 1 March or as late as 4 April). Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

saw this discovery as an excellent tool to drive a wedge between Poland, Western Allies, and the Soviet Union, and reinforce the Nazi propaganda

Nazi propaganda

Propaganda, the coordinated attempt to influence public opinion through the use of media, was skillfully used by the NSDAP in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's leadership of Germany...

line about the horrors of Bolshevism and American and British subservience to it. After extensive preparation, on 13 April, Berlin Radio broadcast to the world that German military forces in the Katyn forest near Smolensk had uncovered "a ditch ... 28 metres long and 16 metres wide [92 ft by 52 ft], in which the bodies of 3,000 Polish officers were piled up in 12 layers." The broadcast went on to charge the Soviets with carrying out the massacre in 1940.

The Germans brought in a European commission consisting of twelve forensic experts and their staffs from Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

, Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

, Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Croatia

Croatia

Croatia , officially the Republic of Croatia , is a unitary democratic parliamentary republic in Europe at the crossroads of the Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. Its capital and largest city is Zagreb. The country is divided into 20 counties and the city of Zagreb. Croatia covers ...

, the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

, and Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

. They were so intent on proving that the Soviets were behind the massacre that they even included some Allied prisoners of war. After the war, two of the twelve, the Bulgarian, Marko Markov and the Czech, Frantisek Hajek, with their countries occupied by the Soviet Union, were forced to recant their evidence, defending the Soviets and blaming the Germans. The Katyn massacre was beneficial to Nazi Germany, which used it to discredit the Soviet Union. Goebbels wrote in his diary on 14 April 1943: "We are now using the discovery of 12,000 Polish officers, murdered by the GPU

State Political Directorate

The State Political Directorate was the secret police of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1934...

, for anti-Bolshevik propaganda on a grand style. We sent neutral journalists and Polish intellectuals to the spot where they were found. Their reports now reaching us from ahead are gruesome. The Führer has also given permission for us to hand out a drastic news item to the German press. I gave instructions to make the widest possible use of the propaganda material. We shall be able to live on it for a couple weeks." The Germans won a major propaganda victory, portraying communism as a danger to Western civilization.

The Soviet government immediately denied the German charges and claimed that the Polish prisoners of war had been engaged in construction work west of Smolensk and consequently were captured and executed by invading German units in August 1941. The Soviet response on 15 April to the initial German broadcast of 13 April, prepared by the Soviet Information Bureau

Soviet Information Bureau

Soviet Information Bureau , commonly known as Sovinformburo ) was a leading Soviet news agency in 1941 - 1961. It was established on June 24, 1941, shortly after the opening of the Eastern Front of World War II by a directive of Sovnarkom and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the...

, stated that "[...]Polish prisoners-of-war who in 1941 were engaged in construction work west of Smolensk and who [...] fell into the hands of the German-Fascist hangmen [...]."

In April 1943 the Polish government-in-exile insisted on bringing the matter to the negotiation table with the Soviets and on opening an investigation by the International Red Cross. Stalin, in response, accused the Polish government of collaborating with Nazi Germany, broke off diplomatic relations with it, and started a campaign to get the Western Allies to recognize the alternative Polish pro-Soviet government in Moscow led by Wanda Wasilewska

Wanda Wasilewska

Wanda Wasilewska was a Polish and Soviet novelist and communist political activist who played an important role in the creation of a Polish division of the Soviet Red Army during World War II and the formation of the Polish People's Republic....

. Sikorski died in an air crash in July—an event that was convenient to the Allied leaders.

Soviet actions

When, in September 1943, GoebbelsJoseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

was informed that the German army had to withdraw from the Katyn area, he wrote a prediction in his diary. His entry for 29 September 1943 reads: "Unfortunately we have had to give up Katyn. The Bolsheviks undoubtedly will soon 'find' that we shot 12,000 Polish officers. That episode is one that is going to cause us quite a little trouble in the future. The Soviets are undoubtedly going to make it their business to discover as many mass graves as possible and then blame it on us."

Having retaken the Katyn area almost immediately after the Red Army had recaptured Smolensk, around September–October 1943, NKVD forces began a cover-up. A cemetery the Germans had permitted the Polish Red Cross to build was destroyed and other evidence removed. Witnesses were "interviewed", and threatened with being arrested as German collaborators if their testimonies disagreed with the official line. Since none of documents found on the dead had dates later than April 1940 the Soviet secret police planted false evidence that pushed the massacre date forward to the summer of 1941 when the Nazis controlled the area. A preliminary report was issued by NKVD operatives Vsevolod Merkulov and Sergei Kruglov, dated 10–11 January 1944, concluding that the Polish officers were shot by the Germans.

In January 1944, the Soviet Union sent another commission, the Special Commission for Determination and Investigation of the Shooting of Polish Prisoners of War by German-Fascist Invaders in Katyn Forest to the site; the very name of the commission implied a predestined conclusion. It was headed by Nikolai Burdenko

Nikolai Burdenko

Nikolay Nilovich Burdenko was a Russian and Soviet surgeon, the founder of the Russian neurosurgery. He was Surgeon-General of the Red Army , an academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences , an academician and the first director of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR , a Hero of Socialist...

, the President of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR (hence the commission is often known as the "Burdenko Commission"), who was appointed by Moscow, to investigate the incident. Its members included prominent Soviet figures such as the writer Alexei Tolstoy

Alexei Tolstoy

Alexei Tolstoy may refer to:* Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Russian poet, novelist and playwright* Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, , Russian writer and playwright who specialized in science fiction and historical novels...

, but no foreign personnel were allowed to join the Commission. The Burdenko Commission exhumed the bodies, rejected the 1943 German findings that the Poles were shot by the Soviets, assigned the guilt to the Germans and concluded that all the shootings were done by German occupation forces in autumn of 1941. Despite lack of evidence, it also blamed the Germans for shooting Russian prisoners of war used as labor to dig the pits. It is uncertain how many members of the commission were duped by the falsified reports and evidence, and how many suspected the truth; Cienciala and Materski note that the Commission had no choice but to issue findings in line with the Merkulov-Kruglov report, and that Burdenko himself likely was aware of the cover up. He reportedly admitted something like that to friends and family shortly before his death. The Burdenko commission's conclusions would be consistently cited by Soviet sources until the official admission of guilt by the Soviet government on 13 April 1990.

In January 1944, the Soviets also invited a group of over a dozen mainly American and British journalists, accompanied by Kathleen Harriman, the daughter of the new American ambassador W. Averell Harriman

W. Averell Harriman

William Averell Harriman was an American Democratic Party politician, businessman, and diplomat. He was the son of railroad baron E. H. Harriman. He served as Secretary of Commerce under President Harry S. Truman and later as the 48th Governor of New York...

), and John Melby

John F. Melby

John Fremont Melby was a United States diplomat, who served in Russia from 1943 to 1945 and in China from 1945 to 1948. He held other State Department positions until 1953, when he was dismissed as a security risk because of his long and intimate association with the playwright Lillian Hellman,...

third secretary at the American embassy in Moscow, to Katyn. That Melby and Harriman were included was regarded by some at the time as an attempt by the Soviets to lend official weight to their propaganda. Melby's report pointed out the deficiencies in the Soviet case: problematic witnesses, attempts to question the witnesses was discouraged, statements by witnesses were obviously given as a result of rote memorization and that "the show was put on for the benefit of the correspondents". Nevertheless Melby, at the time, felt that on balance the Russian case was convincing. Harriman's report reached the same conclusion and both were asked to explain after the war why their conclusions didn't correspond to their findings with the suspicion that they were reporting what State Department wanted to hear. The journalists were less impressed, and not totally convinced by Soviet stage demonstration.

Western response

The growing Polish-Soviet crisis was beginning to threaten Western-Soviet relations at a time when the Poles' importance to the Allies, significant in the first years of the war, was beginning to fade, due to the entry into the conflict of the military and industrial giants, the Soviet Union and the United States. In retrospective review of records, both British Prime Minister Winston ChurchillWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

and U.S. President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

were increasingly torn between their commitments to their Polish ally and the demands by Stalin and his diplomats.

In private, Churchill agreed that the atrocity was likely carried out by the Soviets. According to Edward Raczyński

Edward Raczynski (1891-1993)

Edward Bernard Raczyński was a Polish aristocrat, diplomat, writer, politician and President of Poland in exile ....

, Churchill admitted on 15 April 1943 during a conversation with General Sikorski: "Alas, the German revelations are probably true. The Bolsheviks can be very cruel." However, at the same time, on 24 April 1943 Churchill assured the Soviets: "We shall certainly oppose vigorously any 'investigation' by the International Red Cross or any other body in any territory under German authority. Such investigation would be a fraud and its conclusions reached by terrorism." Unofficial or classified UK documents concluded that Soviet guilt was a "near certainty", but the alliance with the Soviets was deemed to be more important than moral issues; thus the official version supported the Soviets, up to censoring

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

any contradictory accounts. Churchill asked Owen O'Malley

Sir Owen St. Clair O'Malley

Sir Owen St Clair O'Malley KCMG was a British diplomat. He was Ambassador to Hungary between 1939 and 1941. He was British ambassador to the Polish government in exile in London during the World War II...

to investigate the issue, but in a note to Foreign Secretary he noted: "All this is merely to ascertain the facts, because we should none of us ever speak a word about it.". O'Malley pointed out several inconsistencies and near impossibilities in the Soviet version. Later, Churchill sent a copy of the report to Roosevelt on the 13th August 1943. The report deconstructed the Soviet account of the massacre and alluded to the political consequences within a strongly moral framework but recognized that there was no viable alternative to the existing policy. No comment by Roosevelt on the O'Malley report has been found. Churchill's own post-war account of the Katyn affair gives little further insight. In his memoirs, he refers to the 1944 Soviet inquiry into the massacre, which found the Germans guilty and adds, "belief seems an act of faith."

At the beginning of 1944, Ron Jeffery

Ron Jeffery

Not to be confused with Ron Jeremy.Ron Jeffery , also Józef Kawala, Stanisław Jasiński, Sporn and Botkin, was an English soldier and an agent of British and Polish intelligence during World War II...

an agent of British and Polish intelligence in occupied Poland eluded the Abwehr

Abwehr

The Abwehr was a German military intelligence organisation from 1921 to 1944. The term Abwehr was used as a concession to Allied demands that Germany's post-World War I intelligence activities be for "defensive" purposes only...

and travelled to London with a report from Poland to the British government. His efforts were at first highly regarded but subsequently ignored by the British, which a disillusioned Jeffery attributed to the treachery of Kim Philby

Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby was a high-ranking member of British intelligence who worked as a spy for and later defected to the Soviet Union...

and other high-ranking communist agents entrenched in the British system. Jeffery tried to inform the British government about the Katyn massacre but was as a result released from the Army.

In the United States a similar line was taken, notwithstanding two official intelligence reports into the Katyn massacre which contradicted the official position. In 1944, Roosevelt assigned his special emissary to the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

, Navy Lieutenant Commander George Earle, to produce a report on Katyn. Earle concluded that the massacre was committed by the Soviet Union. Having consulted with Elmer Davis

Elmer Davis

Elmer Davis was a well-known news reporter, author, the Director of the United States Office of War Information during World War II and a Peabody Award recipient.-Education and early career:...

, the director of the Office of War Information, Roosevelt rejected the conclusion (officially), declared that he was convinced of Nazi Germany's responsibility, and ordered that Earle's report be suppressed. When Earle formally requested permission to publish his findings, the President issued a written order to desist. Earle was reassigned and spent the rest of the war in American Samoa

American Samoa

American Samoa is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the sovereign state of Samoa...

.

A further report in 1945, supporting the same conclusion, was produced and stifled. In 1943, two U.S. POWs – Lt. Col. Donald B. Stewart and Col. John H. Van Vliet – had been taken by Germans to Katyn for an international news conference. Later, in 1945, Van Vliet submitted a report concluding that the Soviets were responsible for the massacre. His superior, Maj. Gen. Clayton Bissell

Clayton Bissell

Major General Clayton Lawrence Bissell was born in Kane, Pennsylvania, in 1896. He graduated from Valparaiso University, Indiana, in 1917 with a degree of doctor of laws. In his role as Gen...

, Gen. George Marshall

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense...

's assistant chief of staff for intelligence, destroyed the report. During the 1951–1952 Congressional investigation into Katyn, Bissell defended his action before Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

, arguing that it was not in the U.S. interest to antagonize an ally (Soviet Union) whose assistance was still needed against Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

.

At the Nuremberg trials

From 28 December 1945 to 4 January 1946, seven servicemen of the German Wehrmacht were tried by a Soviet military court in LeningradSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

. One of them, Arno Diere, was charged with helping to dig the Katyn graves during the execution. Diere, who was accused of murder using machine-guns in Soviet villages, confessed to having taken part in burial (though not the execution) of 15–20 thousand Polish POWs in Katyn. For this he was spared execution and was given 15 years of hard labor. His confession was full of absurdities, and thus he was not used as a Soviet prosecution witness during the Nuremberg trials

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

. In a note of 29 November 1954 he recanted his confession, claiming that he was forced to confess by the investigators.

At the London conference that drew up the indictments of German war crimes before the Nuremberg trials, the Soviet negotiators put forward the allegation, "In September 1941, 925 Polish officers who were prisoners of war were killed in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk." The U.S. negotiators agreed to include it, but were "embarrassed" by the inclusion (noting that the allegation had been debated extensively in the press) and concluded that it would be up to the Soviets to sustain it. At the trials in 1946, Soviet General Roman Rudenko

Roman Rudenko

Roman Andreyevich Rudenko was a Soviet lawyer. He was the prosecutor of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1944-1953 and Chief prosecutor of the entire Soviet Union from 1953. He is also well known for acting as the Soviet Chief Prosecutor at the main trial of the major Nazi war...

, raised the indictment, stating that "one of the most important criminal acts for which the major war criminals are responsible was the mass execution of Polish prisoners of war shot in the Katyn forest near Smolensk by the German fascist invaders," but failed to make the case and the U.S. and British judges dismissed the charges. It was not the purpose of the court to determine whether Germany or the Soviet Union was responsible for the crime, but rather to attribute the crime to at least one of the defendants, which the court was unable to do.

Cold War views

In 1951 and 1952, with the Korean WarKorean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

as a background, a U.S. Congressional investigation chaired by Rep. Ray J. Madden

Ray J. Madden

Ray John Madden was a United States Representative from Indiana. He was born in Waseca, Minnesota. He attended the public schools and Sacred Heart Academy in his native city. He graduated from the law department of Creighton University with an LL.B...

and known as the Madden Committee investigated the Katyn massacre. It concluded that the Poles had been killed by the Soviets and recommended that the Soviets be tried before the International Court of Justice

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

. However, the question of responsibility still remained controversial in the West as well as behind the Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

. In the United Kingdom in the late 1970s plans for a memorial to the victims bearing the date 1940 (rather than 1941) were condemned as provocative in the political climate of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

. It has also been alleged that the choice made in 1969 for the location of the Byelorussian SSR

Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union. It was one of the four original founding members of the Soviet Union in 1922, together with the Ukrainian SSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic...

war memorial at the former Belarusian village named Khatyn, a site of a 1943 Nazi massacre

Khatyn massacre

Khatyn, Chatyń was a village in Belarus, in Lahojsk district, Minsk Voblast. On March 22, 1943, the population of the village was massacred during World War II by the 118th Schutzmannschaft battalion, formed in July 1942 in Kiev, mostly from Ukrainian collaborators, prisoners of war and...

have been made to cause confusion with Katyn. The two names are similar or identical in many languages, and were often confused.

In Poland, the pro-Soviet authorities covered up the matter in accordance with the official Soviet propaganda line, deliberately censoring any sources that might provide information about the crime. Katyn was a forbidden topic in postwar Poland

History of Poland (1945–1989)

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Soviet Communist dominance imposed after the end of World War II over the People's Republic of Poland...

. Not only did government censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

suppress all references to it, but even mentioning the atrocity was dangerous. However, in 1981, Polish trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

Solidarity erected a memorial with the simple inscription "Katyn, 1940". It was confiscated by the police and replaced with an official monument with the inscription: "To the Polish soldiers—victims of Hitlerite fascism—reposing in the soil of Katyn". Nevertheless, every year on All Souls Day

Zaduszki

Zaduszki is a Polish tradition of lighting candles and visiting the graves of the relatives on All Souls Day. Its origins can be traced to the times of Slavic mythology....

, similar memorial crosses were erected at Powązki cemetery

Powazki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery , also known as the Stare Powązki is a historic cemetery located in the Wola district, western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city, and one of the oldest...

and numerous other places in Poland, only to be dismantled by the police. Katyn remained a political taboo in communist Poland until the fall of communism

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

in 1989.

In the Soviet Union during the 1950s, the head of KGB, Aleksandr Shelepin proposed and carried out a destruction of many documents related to the Katyn massacre in order to minimize the chance that the truth would be revealed. His 3 March 1959 note to Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles and with the proposal to destroy their personal files, became one of the documents that were preserved and eventually made public.

Revelations

From the late 1980s on there was increasing pressure on both the Polish and Soviet governments to release documents related to the massacre. Polish academics tried to include Katyn in the agenda of the 1987 joint Polish-Soviet commission to investigate censored episodes of the Polish-Russian history. In 1989 Soviet scholars revealed that Joseph Stalin had indeed ordered the massacre, and in 1990 Mikhail GorbachevMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is a former Soviet statesman, having served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991, and as the last head of state of the USSR, having served from 1988 until its dissolution in 1991...

admitted that the NKVD had executed the Poles and confirmed two other burial sites similar to the site at Katyn: Mednoye

Mednoye

Mednoye is a village in Kalininsky District of Tver Oblast, Russia, located on the Tvertsa River, 28 km west of Tver, by the Moscow–St.Petersburg highway. Population: 3,047 ....

and Piatykhatky.

On 30 October 1989 Gorbachev allowed a delegation of several hundred Poles, organized by the Polish association Families of Katyń Victims, to visit the Katyn memorial. This group included former U.S. national security advisor

National Security Advisor (United States)

The Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, commonly referred to as the National Security Advisor , serves as the chief advisor to the President of the United States on national security issues...

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski is a Polish American political scientist, geostrategist, and statesman who served as United States National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981....

. A Mass

Mass (liturgy)

"Mass" is one of the names by which the sacrament of the Eucharist is called in the Roman Catholic Church: others are "Eucharist", the "Lord's Supper", the "Breaking of Bread", the "Eucharistic assembly ", the "memorial of the Lord's Passion and Resurrection", the "Holy Sacrifice", the "Holy and...

was held and banners hailing the Solidarity movement were laid. One mourner affixed a sign reading "NKVD" on the memorial, covering the word "Nazis" in the inscription such that it read "In memory of Polish officers murdered by the NKVD in 1941." Several visitors scaled the fence of a nearby KGB compound and left burning candles on the grounds. Brzezinski commented that:

It isn't a personal pain which has brought me here, as is the case in the majority of these people, but rather recognition of the symbolic nature of Katyń. Russians and Poles, tortured to death, lie here together. It seems very important to me that the truth should be spoken about what took place, for only with the truth can the new Soviet leadership distance itself from the crimes of Stalin and the NKVD. Only the truth can serve as the basis of true friendship between the Soviet and the Polish peoples. The truth will make a path for itself. I am convinced of this by the very fact that I was able to travel here.

Brzezinski further stated that:

The fact that the Soviet government has enabled me to be here—and the Soviets know my views—is symbolic of the breach with Stalinism that perestroikaPerestroikaPerestroika was a political movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during 1980s, widely associated with the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev...

represents.

His remarks were given extensive coverage on Soviet television. At the ceremony he placed a bouquet of red roses bearing a handwritten message penned in both Polish and English: "For the victims of Stalin and the NKVD. Zbigniew Brzezinski."

On 13 April 1990, the forty-seventh anniversary of the discovery of the mass graves, the USSR formally expressed "profound regret" and admitted Soviet secret police responsibility. The day was declared a worldwide Katyn Memorial Day .

Recent developments

Russia and Poland remained divided on the legal description of the Katyn crime. The Poles considered it a case of genocide and demanded further investigations, as well as complete disclosure of Soviet documents.After Poles and Americans discovered further evidence in 1991 and 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin was the first President of the Russian Federation, serving from 1991 to 1999.Originally a supporter of Mikhail Gorbachev, Yeltsin emerged under the perestroika reforms as one of Gorbachev's most powerful political opponents. On 29 May 1990 he was elected the chairman of...

released the top-secret documents from the sealed "Package №1." and transferred them to the new Polish president Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa is a Polish politician, trade-union organizer, and human-rights activist. A charismatic leader, he co-founded Solidarity , the Soviet bloc's first independent trade union, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, and served as President of Poland between 1990 and 95.Wałęsa was an electrician...

, Among the documents was a proposal by Lavrenty Beria, dated 5 March 1940, to execute 25,700 Poles from Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobels camps, and from certain prisons of Western Ukraine and Belarus, signed by Stalin (among others). Another document transferred to the Poles was Aleksandr Shelepin's 3 March 1959 note to Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles, as well as a proposal to destroy their personal files to reduce the possibility that documents related to the massacre would be uncovered later. The revelations were also publicized in the Russian press, where they were interpreted as being one outcome of an ongoing power struggle between Yeltsin and Gorbachev.

In 1991, the Chief Military Prosecutor for the Soviet Union began proceedings against P.K. Soprunenko for his role in the Katyn murders, but eventually declined to prosecute because Soprunenko was 83, almost blind, and recovering from a cancer operation. During the interrogation, Soprunenko defended himself by denying his own signature. In June 1998, Yeltsin and Aleksander Kwaśniewski

Aleksander Kwasniewski

Aleksander Kwaśniewski is a Polish politician who served as the President of Poland from 1995 to 2005. He was born in Białogard, and during communist rule he was active in the Socialist Union of Polish Students and was the Minister for Sport in the communist government in the 1980s...

agreed to construct memorial complexes at Katyn and Mednoye, the two NKVD execution sites on Russian soil. However, in September of that year the Russians also raised the issue of Soviet prisoner of war deaths in the camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–1924). About 16,000 to 20,000 POWs died in those camps due to communicable diseases. Some Russian officials argued that it was 'a genocide comparable to Katyń'. A similar claim was raised in 1994; such attempts are seen by some, particularly in Poland, as a highly provocative Russian attempt to create an 'anti-Katyn' and 'balance the historical equation'.

During Kwaśniewski's visit to Russia in September 2004, Russian officials announced that they were willing to transfer all the information on the Katyn massacre to the Polish authorities as soon as it became declassified. In March 2005 the Prosecutor's General Office of the Russian Federation concluded a decade-long investigation of the massacre. Chief Military Prosecutor Alexander Savenkov announced that the investigation was able to confirm the deaths of 1,803 out of 14,542 Polish citizens who had been sentenced to death while in three Soviet camps. He did not address the fate of about 7,000 victims who had been not in POW camps, but in prisons. Savenkov declared that the massacre was not a genocide, that Soviet officials who had been found guilty of the crime were dead and that, consequently, "there is absolutely no basis to talk about this in judicial terms". 116 out of 183 volumes of files gathered during the Russian investigation, were declared to contain state secrets and were classified.

On 22 March 2005 the Polish Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

unanimously passed an act requesting the Russian archives to be declassified. The Sejm also requested Russia to classify the Katyn massacre as a crime of genocide. The resolution stressed that the authorities of Russia "seek to diminish the burden of this crime by refusing to acknowledge it was genocide and refuse to give access to the records of the investigation into the issue, making it difficult to determine the whole truth about the murder and its perpetrators." In 2008, Polish Foreign Ministry asked the government of Russia about alleged footage of the massacre filmed by the NKVD during the killings. Polish officials believe that this footage, as well as further documents showing cooperation of Soviets with the Gestapo during the operations, are the reason for Russia's decision to classify most of documents about the massacre. In June 2008, Russian courts consented to hear a case about the declassification of documents about Katyn and the judicial rehabilitation of the victims. In an interview with a Polish newspaper, Vladimir Putin called Katyn a "political crime."

As late as 2007 a number of pro-Soviet Russian politicians, commentators and Communist party members continued to deny all Soviet guilt, call the released documents fakes, and insist that the original Soviet version – Polish prisoners were shot by Germans in 1941 – is the correct one. In late 2007 and early 2008, several Russian newspapers, including Rossiyskaya Gazeta

Rossiyskaya Gazeta

Rossiyskaya Gazeta is a Russian government daily newspaper of record which publishes the official decrees, statements and documents of state bodies...

, Komsomolskaya Pravda

Komsomolskaya Pravda

Komsomolskaya Pravda is a daily Russian tabloid newspaper, founded on March 13th, 1925. It is published by "Izdatelsky Dom Komsomolskaya Pravda" .- History :...

and Nezavisimaya Gazeta

Nezavisimaya Gazeta

Nezavisimaya Gazeta is a Russian daily newspaper. Published since December 21, 1990.Information ranging from a wide variety of sources, such as reporters, political scientists, historians, art historians, as well as critics are published in the newspaper...

printed stories that implicated the Nazis for the crime, spurring concern that this was done with the tacit approval of the Kremlin. As a result, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance — Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation is a Polish government-affiliated research institute with lustration prerogatives and prosecution powers founded by specific legislation. It specialises in the legal and historical sciences and...

decided to open its own investigation.

On 4 February 2010 the Prime Minister of Russia, Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin served as the second President of the Russian Federation and is the current Prime Minister of Russia, as well as chairman of United Russia and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Russia and Belarus. He became acting President on 31 December 1999, when...

, invited his Polish counterpart, Donald Tusk

Donald Tusk

Donald Franciszek Tusk is a Polish politician who has been Prime Minister of Poland since 2007. He was a co-founder and is chairman of the Civic Platform party....

, to attend a Katyn memorial in April. The visit took place on 7 April 2010, when Tusk and Putin together commemorated the 70th anniversary of the massacre. Before the visit, the 2007 film Katyń

Katyn (film)

Katyń is a 2007 Polish film about the 1940 Katyn massacre, directed by Academy Honorary Award winner Andrzej Wajda. It is based on the book Post Mortem: The Story of Katyn by Andrzej Mularczyk...

was shown on Russian state television for the first time. The Moscow Times

The Moscow Times

The Moscow Times is an English-language daily newspaper published in Moscow, Russia since 1992. The circulation in 2008 stood at 35,000 copies and the newspaper is typically given out for free at places English-language "expats" attend, including hotels, cafés and restaurants, as well as by...

commented that the film's premiere in Russia was likely a result of Putin's intervention.

On 10 April 2010, an aircraft carrying Polish President Lech Kaczyński

Lech Kaczynski