Liberation of Paris

Encyclopedia

The Liberation of Paris (also known as the Battle for Paris) took place during World War II

from 19 August 1944 until the surrender of the occupying German garrison on August 25th. It could be regarded by some as the last battle in the Battle for Normandy

, though that really ended with the crushing of the Wehrmacht

forces between the U.S. Army under Lt. General George S. Patton, Jr., and the British Army

under Field Marshal

Bernard Law Montgomery in the Falaise gap

in western France around the same time. The Liberation of Paris could be regarded as the transitional conclusion of the Allied invasion breakout in Operation Overlord

into a broad-fronted general offensive, though this is a minority opinion.

The capital region of France had been governed by Nazi Germany

since the signing of the Second Compiègne Armistice

in June 1940, when the German Army occupied northern and westmost France, and when the puppet regime of Vichy France

was established in the town of Vichy

in central France.

The Liberation of Paris started with an uprising by the French Resistance

against the German garrison. On August 24th, the French Forces of the Interior

(Forces françaises de l'intérieur, FFI) received reinforcements from the Free French Army of Liberation

and from the U.S. Third Army under General Patton.

This battle marked the liberation of Paris by the U.S. Army and the exile of the Vichy government to Sigmaringen

in Germany. However, there was still much heavy fighting to be done before France was liberated, including the Operation Anvil Dragoon

amphibious landings

in southmost France in September (near Marseilles), along the German-held seaports of western France (such as at Brest

and Dunkirk), in Alsace Lorraine in eastmost France, and in northeastern France, such as along the Rhine River. The Wehrmacht fought doggedly in these areas for the rest of 1944.

(FFI) under Henri Rol-Tanguy

staged an uprising in the French capital. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander

in Western Europe

, did not consider Paris to be a primary objective. Instead, the U.S. Army and the British Army

hoped to make it all the way to Berlin

before the Soviet Army

did, and hence put an end to World War II in Europe, before moving on to the Pacific to finish off the Japanese Empire.

Moreover, General Eisenhower thought that it was too early for a battle in Paris. He wanted to prevent another battle like the Battle of Stalingrad

or the Battle of Leningrad, and he knew that Adolf Hitler

had given orders to raze Paris. This city was considered to be of too great value culturally and historically to risk destruction in a battle. In a siege, it was estimated that 4000 ST (3,628.7 t) of food per day would be needed to supply the population of Paris, plus huge efforts would be required to restore its water supply

, transportation system, electric power

supplies, et cetera. Such tasks would require much time and large numbers of Allied soldiers and military engineer

s.

However, General Charles de Gaulle

of the partially-resurrected French Army

threatened to order the French 2nd Armored Division (2ème DB) into Paris.

Paris was the prize in a contest for power within the French Resistance. The city was the hub of national administration and politics, the center of the railroad system the highway

system of Central France. Paris seemed to be the only place from which France could be governed. The overiding aim of the Resistance was to get rid of the Germans and to bound men of conflicting philosophies, interests, and political persuasions together. De Gaulle had organized the Free French Army outside of France to support his provisional government, but inside France, a large and vociferous contingent of the left wing (politically) challenged de Gaulle's leadership.

On August 24th, delayed by poor decision-making, combat and poor roads, the Free French General Leclerc, commander of the 2nd Armored Division, disobeyed his directly superior American field commander, Major General

Leonard T. Gerow

, and he sent a vanguard (the colonne Dronne) to Paris, with the message that the entire division would be there on the following day. The 9th Armored Company, composed mainly of veterans of the Spanish Civil War

, equipped with American M4 Sherman

tanks, M2 half-track

s, and General Motors Company trucks from the United States

was commanded by Captain Raymond Dronne

. He became one of the first uniformed Allied officers to enter Paris in 1944.

In contrast, by 18 August more than half the railroad workers were on strike and the city was at a standstill. Virtually all the policemen had disappeared from the streets. Several anti-German demonstrations took place, and armed Resistance members appeared openly. The German reaction was less than forthright; prompting small, local Resistance groups, without central direction or discipline, to take possession the next day of police stations, town halls, national ministries, newspaper buildings and the Hôtel de Ville

.

There were perhaps 20,000 Resistance members in Paris, but few were armed. Nevertheless, they destroyed road signs, punctured the tires of German vehicles, cut communication lines, bombed gasoline depots and attacked isolated pockets of German soldiers. But being inadequately armed, members of the Resistance feared open warfare. To avoid it, Resistance leaders persuaded Raoul Nordling

, the Swedish consul-general

in Paris, to negotiate with the German military governor of Groß-Paris and commander of the Paris garrison, general Dietrich von Choltitz

. On the evening of 19 August, the two men arranged a truce, at first for a few hours; it was then extended indefinitely.

The arrangement was somewhat nebulous. Choltitz agreed to recognize certain parts of Paris as belonging to the Resistance. The Resistance, meanwhile, consented to leave particular areas of Paris free to German troops. But no boundaries were drawn, and neither the Germans nor the French were clear about their respective areas. The armistice expired on the 24th.

On 15 August, in Pantin

On 15 August, in Pantin

(the northeastern suburb of Paris from which the Germans had entered the capital in June 1940), 2,200 men and 400 women — all political prisoners — were sent to Buchenwald concentration camp on the last convoy to Germany.

That same day, the employees of the Paris Métro

, the Gendarmerie and police went on strike, followed by postal workers on 16 August. They were joined by workers across the city causing a general strike

to break out on 18 August, the day on which all Parisians were ordered to mobilize by the French Forces of the Interior

.

On 16 August, 35 young FFI members were betrayed by an agent of the Gestapo

. They went to a rendezvous in the Bois de Boulogne

, near the waterfall

, and there they were executed by the Germans. They were machine gun

ned down and then finished off with hand grenade

s.

On 17 August, concerned that explosives were being placed at strategic points around the city by the Germans, Pierre Taittinger

, the chairman of the municipal council, met Choltitz . On being told that Choltitz intended to slow the Allied advance as much as possible, Taittinger and Nordling attempted to persuade Choltitz not to destroy Paris.

On 19 August, columns of German tanks, half-tracks and trucks towing trailers and cars loaded with troops and material, moved down the Champs Élysées. The rumor of the Allies' advance toward Paris was growing.

On 19 August, columns of German tanks, half-tracks and trucks towing trailers and cars loaded with troops and material, moved down the Champs Élysées. The rumor of the Allies' advance toward Paris was growing.

The streets were deserted following the German retreat; suddenly the first skirmishes between French irregulars and the German occupiers commenced. Spontaneously, other people went out in to the streets, some FFI members posted propaganda posters on walls. These posters focused on a general mobilization order, arguing that "the war continues", and calling on the Parisian police, the Republican Guard

, the Gendarmerie

, the Gardes Mobiles, the G.M.R. (Groupe Mobile de Réserve, the police units replacing the army), the gaolkeepers, the patriotic French, "all men from 18 to 50 able to carry a weapon" to join "the struggle against the invader". Other posters were assuring "victory is near" and a "chastisement for the traitors", i.e., the Vichy loyalists. The posters were signed by the "Parisian Committee of the Liberation" in agreement with the Provisional Government of the French Republic

and under the orders of "Regional Chief Colonel Rol", Henri Rol-Tanguy

, commander of the French Forces of the Interior

in the Île de France region

.

As the battle raged, some small mobile units of the Red Cross moved in the city to assist French and German wounded. Later that day, three French résistants were executed by the Germans.

That same day in Pantin, a barge filled with mines

exploded and destroyed the Great Windmills.

On 20 August, barricade

On 20 August, barricade

s began to appear and resistants organized themselves to sustain a siege. Trucks were positioned, trees cut down and trenches dug in the pavement to free paving stones for consolidating the barricades. These materials were transported by men, women, children and old people using wooden carts. Fuel trucks were attacked and captured, other civilian vehicles like the Citroën

Traction Avant sedan captured, painted with camouflage and marked with the FFI emblem. The Resistance would use them to transport ammunition and orders from one barricade to another.

Fort de Romainville

, a Nazi prison

in the outskirts of Paris, was liberated. From October 1940, the Fort held only female prisoners (resistants and hostages), who were jailed, executed or redirected to the camps

. At liberation in August 1944, many abandoned corpses were found in the Fort

's yard.

A temporary ceasefire between von Choltitz and a part of the French Resistance was brokered by Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul-general in Paris. Both sides needed time; the Germans wanted to strengthen their weak garrison with front-line troops, Resistance leaders wanted to strengthen their positions in anticipation of a battle (the resistance lacked ammunition for any prolonged fight).

The German garrison held most of the main monuments and some strongpoints, the Resistance most of the city. The Germans lacked numbers to go on the offensive, the Resistance lacked heavy weapons to attack these strongpoints.

Skirmishes reached their height of intensity on the 22nd when some German units tried to leave their strongpoints. At 09:00 on 23 August, under von Choltitz' orders, the Germans set fire to the Grand Palais

, an FFI stronghold, and tanks fired at the barricades in the streets. Hitler gave the order to inflict maximum damage on the city.

It is estimated that between 800 and 1,000 resistance fighters were killed during the battle for Paris, another 1,500 were wounded.

and the Champs Élysées, while the Americans cleared the eastern part. German resistance had evaporated during the previous night. Two thousand men remained in the Bois de Boulogne

, 700 more were in the Jardin du Luxembourg

. But most had fled or simply awaited capture.

The battle had cost the Free French 2nd Armored Division 71 killed, 225 wounded, 35 tanks, six self-propelled guns, and 111 vehicles, "a rather high ratio of losses for an armoured division" according to historian Jacques Mordal.

Due to American pressure for a white-only liberation force, black French troops were excluded from the triumphal return to Paris on the 25th.

, the newly established headquarters of General Leclerc. Von Choltitz was kept prisoner until April 1947. In his memoir ... Brennt Paris? ("Is Paris Burning?"), first published in 1950, von Choltitz describes himself as the saviour of Paris.

There is controversy about von Choltitz's actual role during the battle, since he is regarded in very different ways in France and Germany. In Germany, he is regarded as a humanist and a hero who saved Paris from urban warfare and destruction. In 1964, Dietrich von Choltitz explained in an interview taped in his Baden Baden home, why he had refused to obey Hitler: "If for the first time I had disobeyed, it was because I knew that Hitler was insane" ("Si pour la première fois j'ai désobéi, c'est parce que je savais qu'Hitler était fou")". According to a 2004 interview which his son Timo gave to the French public channel France 2

, von Choltitz disobeyed Hitler and personally allowed the Allies to take the city safely and rapidly, preventing the French Resistance from engaging in urban warfare that would have destroyed parts of the ciy. He knew the war was lost and decided alone to save the capital.

However, in France this version is seen as a "falsification of history

" since von Choltitz is regarded as a Nazi officer faithful to Hitler. He was involved in many controversial actions:

During the battle for Paris, he:

In a 2004 interview, Resistance veteran Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont

described von Choltitz as a man who "for as long as he could, killed French people and, when he ceased to kill them, it was because he was not able to do so any longer". Kriegel-Valrimont argues "not only do we owe him nothing, but this a shameless falsification of History, to award him any merit." The Libération de Paris documentary film secretly shot during the battle by the Résistance brings evidence of bitter urban warfare that contradicts the von Choltitz father and son version. Despite this, the Larry Collins

and Dominique Lapierre

novel Is Paris Burning? and its film adaptation of the same name

(1966) emphasize von Choltitz as the saviour of the city.

A third source, the transcripts of telephone conversations between von Choltitz and his superiors, found later in the Fribourg

archives and their analysis by German historians, support Kriegel-Valrimont's theory.

Also, Pierre Taittinger and Raoul Nordling both claim it was they who convinced von Choltitz not to destroy Paris as ordered by Hitler. The first published a book in 1984 describing this episode, ...et Paris ne fut pas détruit (... and Paris Was Not Destroyed), which earned him a prize from the Académie Française

.

German losses are estimated at about 3,200 killed and 12,800 prisoners of war

.

On the same day, Charles de Gaulle

On the same day, Charles de Gaulle

, president of the Provisional Government of the French Republic

moved back into the War Ministry on the rue Saint-Dominique. He then made a rousing speech to the crowd from the Hôtel de Ville

.

when some German snipers were still active. According to a famous anecdote, while de Gaulle was marching down the Champs Élysées and entered the Place de la Concorde

, snipers in the Hôtel de Crillon

area shot at the crowd. Someone in the crowd shouted "this is the Fifth Column

!" leading to a misunderstanding, as a 2nd Armored Division tank gunner fired at the Hôtel's actual fifth column (which, after repairs, is a slightly different color.)

A combined Franco-American military parade was organised on the 29th after the arrival of the U.S. Army's 28th Infantry Division

. Joyous crowds greeted the Armée de la Libération and the Americans as liberators, as their vehicles drove down the city streets.

(AMGOT) like those established in Germany and Japan

in 1945.

The AMGOT administration for France was planned by the American Chief of Staff, but de Gaulle's opposition to Eisenhower's strategy, namely moving to the east as soon as possible, passing Paris by in order to reach Berlin before Joseph Stalin

's Red Army

, led to the 2nd Armored Division's breakout toward Paris and the liberation of the French capital. An indication of the French AMGOT's high status was the new French currency, called "Flag Money" (monnaie drapeau), for it featured the French flag on its back. The notes had been printed in the United States and were distributed as a replacement for Vichy currency which had been used until June 1944, up to and including the successful Operation Overlord in Normandy. However, after the liberation of Paris, this short-lived currency was forbidden by GPRF President Charles de Gaulle, who claimed the US dollar standard notes were fakes.

. This replaced the fallen Vichy State

(1940–1944) and united the politically divided French Resistance, drawing Gaullists, nationalists, communists and anarchists, into a new "national unanimity" government established on 9 September 1944.

In his speech, de Gaulle insisted on the role played by the French and on the necessity for the French people to do their "duty of war" in the Allies' last campaigns to complete the liberation of France and to advance into the Benelux

countries and Germany. De Gaulle wanted France to be among "the victors" in order to evade the AMGOT threat. Two days later, on 28 August, the FFI, called "the combatants without uniform", were incorporated in the New French Army (nouvelle armée française) which was fully equipped with U.S. equipment (such as uniforms, helmets, weapons and vehicles), and still used until after the Algerian War in the 1960s.

A point of strong disagreement between de Gaulle and the Big Three

A point of strong disagreement between de Gaulle and the Big Three

, (Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill), was that the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), established on 3 June 1944, was not recognized as the legitimate representative of France. Even though de Gaulle had been recognized as the leader of Free France by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

back in 28 June 1940, his GPRF presidency had not resulted from democratic elections. However, three months after the liberation of Paris and one month after the new "unanimity government", the Big Three recognized the GPRF on 23 October 1944.

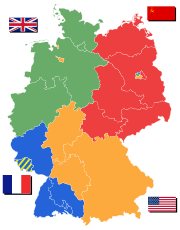

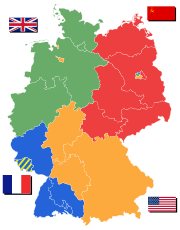

In his liberation of Paris speech, de Gaulle argued "It will not be enough that, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, we have got rid of him [the Germans] from our home for us to be satisfied after what happened. We want to enter his territory as it should be, as victors", clearly showing his ambition that France be considered one of the World War II victors just like the Big Three. This perspective was not shared by the western Allies, as was demonstrated in the German Instrument of Surrender's First Act. The French occupation zones in Germany

and in West Berlin

cemented this ambition, leading to some frustration, which became part of the deeper Western betrayal

sentiment. This sentiment was felt by other European Allies, especially Poland

, whose proposition that they be part of the occupation of Germany was rejected by the Soviets; the latter taking the view that they had liberated the Poles from the Nazis which thus put them under the influence of the USSR.

(a paramilitary militia)—which was established by Sturmbannführer

Joseph Darnand

who hunted the Resistance with the Gestapo

—were made prisoners in a post-liberation purge

known as the Épuration légale

(Legal purge). However, some were executed without trial. The women accused of "horizontal collaboration

" because of their sexual relationships with Germans during the occupation, were arrested, had their heads shaved, then exhibited and were sometimes mauled by crowds.

On 17 August, Pierre Laval

was taken to Belfort

by the Germans. On 20 August, under German military escort, Marshal Philippe Pétain

was forcibly moved to Belfort, and on 7 September to Sigmaringen

, a French enclave in Germany, where 1,000 of his followers (including Louis-Ferdinand Céline

) joined him. There they established the government of Sigmaringen, challenging the legitimacy of de Gaulle's Provisional Government of the French Republic. As a sign of protest over his forced move, Pétain refused to take office, and was eventually replaced by Fernand de Brinon

. The Vichy government in exile

ended in April 1945.

Leclerc, whose 2nd Armored Division was held in high regard by the French people, led the Far East Expeditionary Forces

Leclerc, whose 2nd Armored Division was held in high regard by the French people, led the Far East Expeditionary Forces

(FEFEO) that sailed to French Indochina

then occupied by the Japanese

in 1945.

FEFEO recruiting posters depicted a Sherman tank painted with the cross of Lorraine

with the caption "Yesterday Strasbourg

, tomorrow Saigon, join in!" as a reference to the liberation of Paris by Leclerc's armored division and the role this formation subsequently played in the liberation of Strasbourg. The war effort for the liberation of French Indochina through the FEFEO was presented as propaganda by the continuation of the liberation of France and part of the same "duty of war".

While Vichy France collaborated with Japan in French Indochina after the 1940 invasion and later established a Japanese embassy in Sigmaringen, de Gaulle had declared war on Japan on 8 December 1941 following the attack on Pearl Harbor

and created local anti-Japanese resistance units called Corps Léger d'Intervention

(CLI) in 1943. On 2 September 1945, General Leclerc signed the armistice with Japan on behalf of the Provisional Government of the French Republic onboard the U.S. battleship .

On 16 May 2007, following his election as President of the Fifth French Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy

On 16 May 2007, following his election as President of the Fifth French Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy

organized an homage to the 35 French Resistance martyr

s executed by the Germans on 16 August 1944 during the liberation. French historian Max Gallo

narrated the events that occurred in the Bois de Boulogne woods, and a Parisian schoolgirl read young French resistant Guy Môquet

's (17) final letter. During his speech, Sarkozy announced this letter would now be read in all French schools to remember the resistance spirit. Following the speech, the chorale of the French Republican Guard

closed the homage ceremony by singing the French Resistance's anthem Le Chant des Partisans

("the partisans' song"). Following this occasion, the new President traveled to Berlin to meet German chancellor Angela Merkel

as a symbol of the Franco-German reconciliation

.

("the liberation of Paris"), whose original title was l'insurrection Nationale inséparable de la Libération Nationale ("the national insurrection inseparable from the national liberation"), was a short documentary film secretly shot over 16–27 August by the French Resistance. It was released in French theatres on 1 September.

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

from 19 August 1944 until the surrender of the occupying German garrison on August 25th. It could be regarded by some as the last battle in the Battle for Normandy

Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the code name for the Battle of Normandy, the operation that launched the invasion of German-occupied western Europe during World War II by Allied forces. The operation commenced on 6 June 1944 with the Normandy landings...

, though that really ended with the crushing of the Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

forces between the U.S. Army under Lt. General George S. Patton, Jr., and the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

under Field Marshal

Field Marshal

Field Marshal is a military rank. Traditionally, it is the highest military rank in an army.-Etymology:The origin of the rank of field marshal dates to the early Middle Ages, originally meaning the keeper of the king's horses , from the time of the early Frankish kings.-Usage and hierarchical...

Bernard Law Montgomery in the Falaise gap

Falaise pocket

The battle of the Falaise Pocket, fought during the Second World War from 12 to 21 August 1944, was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy...

in western France around the same time. The Liberation of Paris could be regarded as the transitional conclusion of the Allied invasion breakout in Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the code name for the Battle of Normandy, the operation that launched the invasion of German-occupied western Europe during World War II by Allied forces. The operation commenced on 6 June 1944 with the Normandy landings...

into a broad-fronted general offensive, though this is a minority opinion.

The capital region of France had been governed by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

since the signing of the Second Compiègne Armistice

Armistice with France (Second Compiègne)

The Second Armistice at Compiègne was signed at 18:50 on 22 June 1940 near Compiègne, in the department of Oise, between Nazi Germany and France...

in June 1940, when the German Army occupied northern and westmost France, and when the puppet regime of Vichy France

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

was established in the town of Vichy

Vichy

Vichy is a commune in the department of Allier in Auvergne in central France. It belongs to the historic province of Bourbonnais.It is known as a spa and resort town and was the de facto capital of Vichy France during the World War II Nazi German occupation from 1940 to 1944.The town's inhabitants...

in central France.

The Liberation of Paris started with an uprising by the French Resistance

French Resistance

The French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

against the German garrison. On August 24th, the French Forces of the Interior

French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior refers to French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation of these groups to FFI occurred as France's status changed from that of an occupied nation...

(Forces françaises de l'intérieur, FFI) received reinforcements from the Free French Army of Liberation

Free French Forces

The Free French Forces were French partisans in World War II who decided to continue fighting against the forces of the Axis powers after the surrender of France and subsequent German occupation and, in the case of Vichy France, collaboration with the Germans.-Definition:In many sources, Free...

and from the U.S. Third Army under General Patton.

This battle marked the liberation of Paris by the U.S. Army and the exile of the Vichy government to Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen is a town in southern Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg. Situated on the upper Danube, it is the capital of the Sigmaringen district....

in Germany. However, there was still much heavy fighting to be done before France was liberated, including the Operation Anvil Dragoon

Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon was the Allied invasion of southern France on August 15, 1944, during World War II. The invasion was initiated via a parachute drop by the 1st Airborne Task Force, followed by an amphibious assault by elements of the U.S. Seventh Army, followed a day later by a force made up...

amphibious landings

Amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is the use of naval firepower, logistics and strategy to project military power ashore. In previous eras it stood as the primary method of delivering troops to non-contiguous enemy-held terrain...

in southmost France in September (near Marseilles), along the German-held seaports of western France (such as at Brest

Brest

-Places:* Brest, Belarus ** Brest Fortress** Brest Railway Museum, the first outdoor railway museum in Belarus* Brest, France...

and Dunkirk), in Alsace Lorraine in eastmost France, and in northeastern France, such as along the Rhine River. The Wehrmacht fought doggedly in these areas for the rest of 1944.

Background

Allied strategy emphasized destroying German forces retreating towards the Rhine, when the French ResistanceFrench Resistance

The French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

(FFI) under Henri Rol-Tanguy

Henri Rol-Tanguy

Henri Rol-Tanguy was a French communist and a leader in the French Resistance during World War II.-Biography:...

staged an uprising in the French capital. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Western Allies during World War II, and is currently used only within NATO. Dwight Eisenhower served as Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary...

in Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

, did not consider Paris to be a primary objective. Instead, the U.S. Army and the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

hoped to make it all the way to Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

before the Soviet Army

Soviet Army

The Soviet Army is the name given to the main part of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union between 1946 and 1992. Previously, it had been known as the Red Army. Informally, Армия referred to all the MOD armed forces, except, in some cases, the Soviet Navy.This article covers the Soviet Ground...

did, and hence put an end to World War II in Europe, before moving on to the Pacific to finish off the Japanese Empire.

Moreover, General Eisenhower thought that it was too early for a battle in Paris. He wanted to prevent another battle like the Battle of Stalingrad

Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad was a major battle of World War II in which Nazi Germany and its allies fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad in southwestern Russia. The battle took place between 23 August 1942 and 2 February 1943...

or the Battle of Leningrad, and he knew that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

had given orders to raze Paris. This city was considered to be of too great value culturally and historically to risk destruction in a battle. In a siege, it was estimated that 4000 ST (3,628.7 t) of food per day would be needed to supply the population of Paris, plus huge efforts would be required to restore its water supply

Water supply

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavours or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes...

, transportation system, electric power

Electric power

Electric power is the rate at which electric energy is transferred by an electric circuit. The SI unit of power is the watt.-Circuits:Electric power, like mechanical power, is represented by the letter P in electrical equations...

supplies, et cetera. Such tasks would require much time and large numbers of Allied soldiers and military engineer

Military engineer

In military science, engineering refers to the practice of designing, building, maintaining and dismantling military works, including offensive, defensive and logistical structures, to shape the physical operating environment in war...

s.

However, General Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

of the partially-resurrected French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

threatened to order the French 2nd Armored Division (2ème DB) into Paris.

Paris was the prize in a contest for power within the French Resistance. The city was the hub of national administration and politics, the center of the railroad system the highway

Highway

A highway is any public road. In American English, the term is common and almost always designates major roads. In British English, the term designates any road open to the public. Any interconnected set of highways can be variously referred to as a "highway system", a "highway network", or a...

system of Central France. Paris seemed to be the only place from which France could be governed. The overiding aim of the Resistance was to get rid of the Germans and to bound men of conflicting philosophies, interests, and political persuasions together. De Gaulle had organized the Free French Army outside of France to support his provisional government, but inside France, a large and vociferous contingent of the left wing (politically) challenged de Gaulle's leadership.

On August 24th, delayed by poor decision-making, combat and poor roads, the Free French General Leclerc, commander of the 2nd Armored Division, disobeyed his directly superior American field commander, Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

Leonard T. Gerow

Leonard T. Gerow

Leonard Townsend Gerow was a United States Army general.-Early life:Gerow was born in Petersburg, Virginia. The name Gerow is derived from the French name "Giraud". Gerow attended high school in Petersburg and then attended the Virginia Military Institute. He was three times elected class...

, and he sent a vanguard (the colonne Dronne) to Paris, with the message that the entire division would be there on the following day. The 9th Armored Company, composed mainly of veterans of the Spanish Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, equipped with American M4 Sherman

M4 Sherman

The M4 Sherman, formally Medium Tank, M4, was the primary tank used by the United States during World War II. Thousands were also distributed to the Allies, including the British Commonwealth and Soviet armies, via lend-lease...

tanks, M2 half-track

M2 Half Track Car

The M-2 Half Track was an armored vehicle used by the United States during World War II.-History:The half-track design had been evaluated by the US Ordnance department using Citroën-Kégresse vehicles...

s, and General Motors Company trucks from the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

was commanded by Captain Raymond Dronne

Raymond Dronne

Capitaine Raymond Dronne , French civil servant and, following World War II, a politician. He was the first Allied officer to enter Paris as part of the liberation forces during World War II. A volunteer who joined the Free French Forces in Africa in 1940...

. He became one of the first uniformed Allied officers to enter Paris in 1944.

Events timeline

As late as 11 August, nine French Jews were arrested by the French police in Paris. On 16 August, collaboration newspapers were still published and, although food was in short supply, sidewalk cafés were crowded.In contrast, by 18 August more than half the railroad workers were on strike and the city was at a standstill. Virtually all the policemen had disappeared from the streets. Several anti-German demonstrations took place, and armed Resistance members appeared openly. The German reaction was less than forthright; prompting small, local Resistance groups, without central direction or discipline, to take possession the next day of police stations, town halls, national ministries, newspaper buildings and the Hôtel de Ville

Hôtel de Ville, Paris

The Hôtel de Ville |City Hall]]) in :Paris, France, is the building housing the City of Paris's administration. Standing on the place de l'Hôtel de Ville in the city's IVe arrondissement, it has been the location of the municipality of Paris since 1357...

.

There were perhaps 20,000 Resistance members in Paris, but few were armed. Nevertheless, they destroyed road signs, punctured the tires of German vehicles, cut communication lines, bombed gasoline depots and attacked isolated pockets of German soldiers. But being inadequately armed, members of the Resistance feared open warfare. To avoid it, Resistance leaders persuaded Raoul Nordling

Raoul Nordling

Raoul Nordling was a Swedish businessman and diplomat. He was born in Paris and spent most of his life there....

, the Swedish consul-general

Consul (representative)

The political title Consul is used for the official representatives of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, and to facilitate trade and friendship between the peoples of the two countries...

in Paris, to negotiate with the German military governor of Groß-Paris and commander of the Paris garrison, general Dietrich von Choltitz

Dietrich von Choltitz

General der Infanterie Dietrich von Choltitz was the German military governor of Paris during the closing days of the German occupation of that city during World War II...

. On the evening of 19 August, the two men arranged a truce, at first for a few hours; it was then extended indefinitely.

The arrangement was somewhat nebulous. Choltitz agreed to recognize certain parts of Paris as belonging to the Resistance. The Resistance, meanwhile, consented to leave particular areas of Paris free to German troops. But no boundaries were drawn, and neither the Germans nor the French were clear about their respective areas. The armistice expired on the 24th.

General strike (15–18 August 1944)

Pantin

Pantin is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris. It is one of the most densely populated municipalities in Europe. Its post code is 93500.Pantin was once the site of Motobecane's operations...

(the northeastern suburb of Paris from which the Germans had entered the capital in June 1940), 2,200 men and 400 women — all political prisoners — were sent to Buchenwald concentration camp on the last convoy to Germany.

That same day, the employees of the Paris Métro

Paris Métro

The Paris Métro or Métropolitain is the rapid transit metro system in Paris, France. It has become a symbol of the city, noted for its density within the city limits and its uniform architecture influenced by Art Nouveau. The network's sixteen lines are mostly underground and run to 214 km ...

, the Gendarmerie and police went on strike, followed by postal workers on 16 August. They were joined by workers across the city causing a general strike

General strike

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

to break out on 18 August, the day on which all Parisians were ordered to mobilize by the French Forces of the Interior

French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior refers to French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation of these groups to FFI occurred as France's status changed from that of an occupied nation...

.

On 16 August, 35 young FFI members were betrayed by an agent of the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

. They went to a rendezvous in the Bois de Boulogne

Bois de Boulogne

The Bois de Boulogne is a park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine...

, near the waterfall

Waterfall

A waterfall is a place where flowing water rapidly drops in elevation as it flows over a steep region or a cliff.-Formation:Waterfalls are commonly formed when a river is young. At these times the channel is often narrow and deep. When the river courses over resistant bedrock, erosion happens...

, and there they were executed by the Germans. They were machine gun

Machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic mounted or portable firearm, usually designed to fire rounds in quick succession from an ammunition belt or large-capacity magazine, typically at a rate of several hundred rounds per minute....

ned down and then finished off with hand grenade

Hand grenade

A hand grenade is any small bomb that can be thrown by hand. Hand grenades are classified into three categories, explosive grenades, chemical and gas grenades. Explosive grenades are the most commonly used in modern warfare, and are designed to detonate after impact or after a set amount of time...

s.

On 17 August, concerned that explosives were being placed at strategic points around the city by the Germans, Pierre Taittinger

Pierre Taittinger

Pierre-Charles Taittinger was founder of the famous Taittinger champagne house and chairman of the municipal council of Paris in 1943–1944 during the German occupation of France, in which position he played a role during the Liberation of Paris.-Personal life:Born in Paris, Pierre...

, the chairman of the municipal council, met Choltitz . On being told that Choltitz intended to slow the Allied advance as much as possible, Taittinger and Nordling attempted to persuade Choltitz not to destroy Paris.

FFI uprising (19–23 August 1944)

The streets were deserted following the German retreat; suddenly the first skirmishes between French irregulars and the German occupiers commenced. Spontaneously, other people went out in to the streets, some FFI members posted propaganda posters on walls. These posters focused on a general mobilization order, arguing that "the war continues", and calling on the Parisian police, the Republican Guard

French Republican Guard

The Republican Guard is part of the French Gendarmerie. It is responsible for providing security in the Paris area and for providing guards of honor.Its missions include:...

, the Gendarmerie

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

, the Gardes Mobiles, the G.M.R. (Groupe Mobile de Réserve, the police units replacing the army), the gaolkeepers, the patriotic French, "all men from 18 to 50 able to carry a weapon" to join "the struggle against the invader". Other posters were assuring "victory is near" and a "chastisement for the traitors", i.e., the Vichy loyalists. The posters were signed by the "Parisian Committee of the Liberation" in agreement with the Provisional Government of the French Republic

Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic was an interim government which governed France from 1944 to 1946, following the fall of Vichy France and prior to the Fourth French Republic....

and under the orders of "Regional Chief Colonel Rol", Henri Rol-Tanguy

Henri Rol-Tanguy

Henri Rol-Tanguy was a French communist and a leader in the French Resistance during World War II.-Biography:...

, commander of the French Forces of the Interior

French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior refers to French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation of these groups to FFI occurred as France's status changed from that of an occupied nation...

in the Île de France region

Île-de-France (région)

Île-de-France is the wealthiest and most populated of the twenty-two administrative regions of France, composed mostly of the Paris metropolitan area....

.

As the battle raged, some small mobile units of the Red Cross moved in the city to assist French and German wounded. Later that day, three French résistants were executed by the Germans.

That same day in Pantin, a barge filled with mines

Naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an enemy vessel...

exploded and destroyed the Great Windmills.

Barricade

Barricade, from the French barrique , is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction...

s began to appear and resistants organized themselves to sustain a siege. Trucks were positioned, trees cut down and trenches dug in the pavement to free paving stones for consolidating the barricades. These materials were transported by men, women, children and old people using wooden carts. Fuel trucks were attacked and captured, other civilian vehicles like the Citroën

Citroën

Citroën is a major French automobile manufacturer, part of the PSA Peugeot Citroën group.Founded in 1919 by French industrialist André-Gustave Citroën , Citroën was the first mass-production car company outside the USA and pioneered the modern concept of creating a sales and services network that...

Traction Avant sedan captured, painted with camouflage and marked with the FFI emblem. The Resistance would use them to transport ammunition and orders from one barricade to another.

Fort de Romainville

Fort de Romainville

Fort de Romainville, was built in France in the 1830s and was used as a Nazi concentration camp in World War II.- Use in WWII :...

, a Nazi prison

Concentration camps in France

There were internment camps and concentration camps in France before, during and after World War II. Beside the camps created during World War I to intern German, Austrian and Ottoman civilian prisoners, the Third Republic opened various internment camps for the Spanish refugees fleeing the...

in the outskirts of Paris, was liberated. From October 1940, the Fort held only female prisoners (resistants and hostages), who were jailed, executed or redirected to the camps

Nazi concentration camps

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

. At liberation in August 1944, many abandoned corpses were found in the Fort

Fort de Romainville

Fort de Romainville, was built in France in the 1830s and was used as a Nazi concentration camp in World War II.- Use in WWII :...

's yard.

A temporary ceasefire between von Choltitz and a part of the French Resistance was brokered by Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul-general in Paris. Both sides needed time; the Germans wanted to strengthen their weak garrison with front-line troops, Resistance leaders wanted to strengthen their positions in anticipation of a battle (the resistance lacked ammunition for any prolonged fight).

The German garrison held most of the main monuments and some strongpoints, the Resistance most of the city. The Germans lacked numbers to go on the offensive, the Resistance lacked heavy weapons to attack these strongpoints.

Skirmishes reached their height of intensity on the 22nd when some German units tried to leave their strongpoints. At 09:00 on 23 August, under von Choltitz' orders, the Germans set fire to the Grand Palais

Grand Palais

This article contains material abridged and translated from the French and Spanish Wikipedia.The Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées, commonly known as the Grand Palais , is a large historic site, exhibition hall and museum complex located at the Champs-Élysées in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France...

, an FFI stronghold, and tanks fired at the barricades in the streets. Hitler gave the order to inflict maximum damage on the city.

It is estimated that between 800 and 1,000 resistance fighters were killed during the battle for Paris, another 1,500 were wounded.

Entrance of the 2nd Armored Division and 4th US Infantry division (24–25 August)

On the following morning, an enormous crowd of joyous Parisians welcomed the arrival of the 2nd French Armored Division, which swept the western part of Paris, including the Arc de TriompheArc de Triomphe

-The design:The astylar design is by Jean Chalgrin , in the Neoclassical version of ancient Roman architecture . Major academic sculptors of France are represented in the sculpture of the Arc de Triomphe: Jean-Pierre Cortot; François Rude; Antoine Étex; James Pradier and Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire...

and the Champs Élysées, while the Americans cleared the eastern part. German resistance had evaporated during the previous night. Two thousand men remained in the Bois de Boulogne

Bois de Boulogne

The Bois de Boulogne is a park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine...

, 700 more were in the Jardin du Luxembourg

Jardin du Luxembourg

The Jardin du Luxembourg, or the Luxembourg Gardens, is the second largest public park in Paris The Jardin du Luxembourg, or the Luxembourg Gardens, is the second largest public park in Paris The Jardin du Luxembourg, or the Luxembourg Gardens, is the second largest public park in Paris (224,500 m²...

. But most had fled or simply awaited capture.

The battle had cost the Free French 2nd Armored Division 71 killed, 225 wounded, 35 tanks, six self-propelled guns, and 111 vehicles, "a rather high ratio of losses for an armoured division" according to historian Jacques Mordal.

Due to American pressure for a white-only liberation force, black French troops were excluded from the triumphal return to Paris on the 25th.

German surrender (25 August)

Despite repeated orders from Adolf Hitler that the French capital "must not fall into the enemy's hand except lying in complete debris" to be accomplished by bombing it and blowing up its bridges, von Choltitz, as commander of the German garrison and military governor of Paris, surrendered on 25 August at the Hôtel MeuriceHotel Meurice

Le Meurice is a 5-star hotel in Paris, located opposite the Tuileries Garden, between Place de la Concorde and the Musée du Louvre. This hotel is owned and managed by the Dorchester Collection...

, the newly established headquarters of General Leclerc. Von Choltitz was kept prisoner until April 1947. In his memoir ... Brennt Paris? ("Is Paris Burning?"), first published in 1950, von Choltitz describes himself as the saviour of Paris.

There is controversy about von Choltitz's actual role during the battle, since he is regarded in very different ways in France and Germany. In Germany, he is regarded as a humanist and a hero who saved Paris from urban warfare and destruction. In 1964, Dietrich von Choltitz explained in an interview taped in his Baden Baden home, why he had refused to obey Hitler: "If for the first time I had disobeyed, it was because I knew that Hitler was insane" ("Si pour la première fois j'ai désobéi, c'est parce que je savais qu'Hitler était fou")". According to a 2004 interview which his son Timo gave to the French public channel France 2

France 2

France 2 is a French public national television channel. It is part of the state-owned France Télévisions group, along with France 3, France 4, France 5 and France Ô...

, von Choltitz disobeyed Hitler and personally allowed the Allies to take the city safely and rapidly, preventing the French Resistance from engaging in urban warfare that would have destroyed parts of the ciy. He knew the war was lost and decided alone to save the capital.

However, in France this version is seen as a "falsification of history

Historical revisionism (negationism)

Historical revisionism is either the legitimate scholastic re-examination of existing knowledge about a historical event, or the illegitimate distortion of the historical record such that certain events appear in a more or less favourable light. For the former, i.e. the academic pursuit, see...

" since von Choltitz is regarded as a Nazi officer faithful to Hitler. He was involved in many controversial actions:

- In 1940 and 1941, he gave the orders to burn RotterdamRotterdam BlitzThe Rotterdam Blitz refers to the aerial bombardment of Rotterdam by the German Air Force on 14 May 1940, during the German invasion of the Netherlands in World War II. The objective was to support the German troops fighting in the city, break Dutch resistance and force the Dutch to surrender...

and destroy SevastopolSevastopolSevastopol is a city on rights of administrative division of Ukraine, located on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea peninsula. It has a population of 342,451 . Sevastopol is the second largest port in Ukraine, after the Port of Odessa....

.

During the battle for Paris, he:

- ordered the execution of thirty-five members of the Résistance at the Bois de BoulogneBois de BoulogneThe Bois de Boulogne is a park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine...

waterfall on 16 August.- ordered the destruction of the PantinPantinPantin is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris. It is one of the most densely populated municipalities in Europe. Its post code is 93500.Pantin was once the site of Motobecane's operations...

great windmills on 19 August (in order to starve the population). - ordered the burning of the Grand PalaisGrand PalaisThis article contains material abridged and translated from the French and Spanish Wikipedia.The Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées, commonly known as the Grand Palais , is a large historic site, exhibition hall and museum complex located at the Champs-Élysées in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, France...

on 23 August, occupied by the FFI.

- ordered the destruction of the Pantin

In a 2004 interview, Resistance veteran Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont

Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont

Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont was a militant communist who took part in the French Resistance during the Second World War, and a French politician...

described von Choltitz as a man who "for as long as he could, killed French people and, when he ceased to kill them, it was because he was not able to do so any longer". Kriegel-Valrimont argues "not only do we owe him nothing, but this a shameless falsification of History, to award him any merit." The Libération de Paris documentary film secretly shot during the battle by the Résistance brings evidence of bitter urban warfare that contradicts the von Choltitz father and son version. Despite this, the Larry Collins

Larry Collins (writer)

Larry Collins, born John Lawrence Collins Jr., , was an American writer.-Life:...

and Dominique Lapierre

Dominique Lapierre

Dominique Lapierre is a French author.-Life:Dominique Lapierre was born in Châtelaillon-Plage, Charente-Maritime, France. At the age of thirteen, he traveled to America with his father who was a diplomat...

novel Is Paris Burning? and its film adaptation of the same name

Is Paris Burning?

Is Paris Burning? is a 1966 film dealing with the 1944 liberation of Paris by rival branches of the French Resistance and the Free French Forces.-Plot:...

(1966) emphasize von Choltitz as the saviour of the city.

A third source, the transcripts of telephone conversations between von Choltitz and his superiors, found later in the Fribourg

Fribourg

Fribourg is the capital of the Swiss canton of Fribourg and the district of Sarine. It is located on both sides of the river Saane/Sarine, on the Swiss plateau, and is an important economic, administrative and educational center on the cultural border between German and French Switzerland...

archives and their analysis by German historians, support Kriegel-Valrimont's theory.

Also, Pierre Taittinger and Raoul Nordling both claim it was they who convinced von Choltitz not to destroy Paris as ordered by Hitler. The first published a book in 1984 describing this episode, ...et Paris ne fut pas détruit (... and Paris Was Not Destroyed), which earned him a prize from the Académie Française

Académie française

L'Académie française , also called the French Academy, is the pre-eminent French learned body on matters pertaining to the French language. The Académie was officially established in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister to King Louis XIII. Suppressed in 1793 during the French Revolution,...

.

German losses are estimated at about 3,200 killed and 12,800 prisoners of war

Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

.

De Gaulle's speech (25 August)

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

, president of the Provisional Government of the French Republic

Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic was an interim government which governed France from 1944 to 1946, following the fall of Vichy France and prior to the Fourth French Republic....

moved back into the War Ministry on the rue Saint-Dominique. He then made a rousing speech to the crowd from the Hôtel de Ville

Hôtel de Ville, Paris

The Hôtel de Ville |City Hall]]) in :Paris, France, is the building housing the City of Paris's administration. Standing on the place de l'Hôtel de Ville in the city's IVe arrondissement, it has been the location of the municipality of Paris since 1357...

.

Victory parades (26 and 29 August)

The speech was followed a day later by a victory parade down the Champs-ÉlyséesChamps-Élysées

The Avenue des Champs-Élysées is a prestigious avenue in Paris, France. With its cinemas, cafés, luxury specialty shops and clipped horse-chestnut trees, the Avenue des Champs-Élysées is one of the most famous streets and one of the most expensive strip of real estate in the world. The name is...

when some German snipers were still active. According to a famous anecdote, while de Gaulle was marching down the Champs Élysées and entered the Place de la Concorde

Place de la Concorde

The Place de la Concorde in area, it is the largest square in the French capital. It is located in the city's eighth arrondissement, at the eastern end of the Champs-Élysées.- History :...

, snipers in the Hôtel de Crillon

Hôtel de Crillon

The Hôtel de Crillon in Paris is one of the oldest luxury hotels in the world. The hotel is located at the foot of the Champs-Élysées and is one of two identical stone palaces on the Place de la Concorde. The Crillon has 103 guest rooms and 44 suites...

area shot at the crowd. Someone in the crowd shouted "this is the Fifth Column

Fifth Column

Fifth Column was a Canadian all-women experimental post-punk band from Toronto, which came about during the early 1980s. They took the name Fifth Column after a military manoeuvre by Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, in which nationalist insurrectionists within besieged Republican...

!" leading to a misunderstanding, as a 2nd Armored Division tank gunner fired at the Hôtel's actual fifth column (which, after repairs, is a slightly different color.)

A combined Franco-American military parade was organised on the 29th after the arrival of the U.S. Army's 28th Infantry Division

U.S. 28th Infantry Division

The 28th Infantry Division is a unit of the Army National Guard and is the oldest division-sized unit in the armed forces of the United States. The division was officially established in 1879 and was later redesignated as the 28th Division in 1917, after the entry of America into the First World War...

. Joyous crowds greeted the Armée de la Libération and the Americans as liberators, as their vehicles drove down the city streets.

AMGOT

From the French point of view, the liberation of Paris by the French themselves rather than by the Allies saved France from a new constitution being imposed by the Allied Military Government for Occupied TerritoriesAllied Military Government for Occupied Territories

The Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories was the form of military rule administered by Allied forces during and after World War II within European territories they occupied.-Notable AMGOT:...

(AMGOT) like those established in Germany and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

in 1945.

The AMGOT administration for France was planned by the American Chief of Staff, but de Gaulle's opposition to Eisenhower's strategy, namely moving to the east as soon as possible, passing Paris by in order to reach Berlin before Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

, led to the 2nd Armored Division's breakout toward Paris and the liberation of the French capital. An indication of the French AMGOT's high status was the new French currency, called "Flag Money" (monnaie drapeau), for it featured the French flag on its back. The notes had been printed in the United States and were distributed as a replacement for Vichy currency which had been used until June 1944, up to and including the successful Operation Overlord in Normandy. However, after the liberation of Paris, this short-lived currency was forbidden by GPRF President Charles de Gaulle, who claimed the US dollar standard notes were fakes.

National unity

Another important factor was the popular uprising in Paris, which allowed the Parisians to liberate themselves from the Germans and gave the newly established Free French government and its president Charles de Gaulle enough prestige and authority to establish the Provisional Government of the French RepublicProvisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic was an interim government which governed France from 1944 to 1946, following the fall of Vichy France and prior to the Fourth French Republic....

. This replaced the fallen Vichy State

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

(1940–1944) and united the politically divided French Resistance, drawing Gaullists, nationalists, communists and anarchists, into a new "national unanimity" government established on 9 September 1944.

In his speech, de Gaulle insisted on the role played by the French and on the necessity for the French people to do their "duty of war" in the Allies' last campaigns to complete the liberation of France and to advance into the Benelux

Benelux

The Benelux is an economic union in Western Europe comprising three neighbouring countries, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. These countries are located in northwestern Europe between France and Germany...

countries and Germany. De Gaulle wanted France to be among "the victors" in order to evade the AMGOT threat. Two days later, on 28 August, the FFI, called "the combatants without uniform", were incorporated in the New French Army (nouvelle armée française) which was fully equipped with U.S. equipment (such as uniforms, helmets, weapons and vehicles), and still used until after the Algerian War in the 1960s.

World War II victor

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

, (Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill), was that the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), established on 3 June 1944, was not recognized as the legitimate representative of France. Even though de Gaulle had been recognized as the leader of Free France by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

back in 28 June 1940, his GPRF presidency had not resulted from democratic elections. However, three months after the liberation of Paris and one month after the new "unanimity government", the Big Three recognized the GPRF on 23 October 1944.

In his liberation of Paris speech, de Gaulle argued "It will not be enough that, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, we have got rid of him [the Germans] from our home for us to be satisfied after what happened. We want to enter his territory as it should be, as victors", clearly showing his ambition that France be considered one of the World War II victors just like the Big Three. This perspective was not shared by the western Allies, as was demonstrated in the German Instrument of Surrender's First Act. The French occupation zones in Germany

Allied Occupation Zones in Germany

The Allied powers who defeated Nazi Germany in World War II divided the country west of the Oder-Neisse line into four occupation zones for administrative purposes during 1945–49. In the closing weeks of fighting in Europe, US forces had pushed beyond the previously agreed boundaries for the...

and in West Berlin

West Berlin

West Berlin was a political exclave that existed between 1949 and 1990. It comprised the western regions of Berlin, which were bordered by East Berlin and parts of East Germany. West Berlin consisted of the American, British, and French occupation sectors, which had been established in 1945...

cemented this ambition, leading to some frustration, which became part of the deeper Western betrayal

Western betrayal

Western betrayal, also called Yalta betrayal, refers to a range of critical views concerning the foreign policies of several Western countries between approximately 1919 and 1968 regarding Eastern Europe and Central Europe...

sentiment. This sentiment was felt by other European Allies, especially Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, whose proposition that they be part of the occupation of Germany was rejected by the Soviets; the latter taking the view that they had liberated the Poles from the Nazis which thus put them under the influence of the USSR.

Legal purge

Several Vichy loyalists involved in the MiliceMilice

The Milice française , generally called simply Milice, was a paramilitary force created on January 30, 1943 by the Vichy Regime, with German aid, to help fight the French Resistance. The Milice's formal leader was Prime Minister Pierre Laval, though its chief of operations, and actual leader, was...

(a paramilitary militia)—which was established by Sturmbannführer

Sturmbannführer

Sturmbannführer was a paramilitary rank of the Nazi Party equivalent to major, used both in the Sturmabteilung and the Schutzstaffel...

Joseph Darnand

Joseph Darnand

Joseph Darnand was a French soldier and later a leader of the Vichy French collaborators with Nazi Germany....

who hunted the Resistance with the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

—were made prisoners in a post-liberation purge

Purge

In history, religion, and political science, a purge is the removal of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, from another organization, or from society as a whole. Purges can be peaceful or violent; many will end with the imprisonment or exile of those purged,...

known as the Épuration légale

Épuration légale

The Épuration légale was the wave of official trials that followed the Liberation of France and the fall of the Vichy Regime...

(Legal purge). However, some were executed without trial. The women accused of "horizontal collaboration

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

" because of their sexual relationships with Germans during the occupation, were arrested, had their heads shaved, then exhibited and were sometimes mauled by crowds.

On 17 August, Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

was taken to Belfort

Belfort

Belfort is a commune in the Territoire de Belfort department in Franche-Comté in northeastern France and is the prefecture of the department. It is located on the Savoureuse, on the strategically important natural route between the Rhine and the Rhône – the Belfort Gap or Burgundian Gate .-...

by the Germans. On 20 August, under German military escort, Marshal Philippe Pétain

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

was forcibly moved to Belfort, and on 7 September to Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen

Sigmaringen is a town in southern Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg. Situated on the upper Danube, it is the capital of the Sigmaringen district....

, a French enclave in Germany, where 1,000 of his followers (including Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Louis-Ferdinand Céline was the pen name of French writer and physician Louis-Ferdinand Destouches . Céline was chosen after his grandmother's first name. He is considered one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, developing a new style of writing that modernized both French and...

) joined him. There they established the government of Sigmaringen, challenging the legitimacy of de Gaulle's Provisional Government of the French Republic. As a sign of protest over his forced move, Pétain refused to take office, and was eventually replaced by Fernand de Brinon

Fernand de Brinon

Fernand de Brinon, Marquis de Brinon was a French lawyer and journalist who was one of the architects of French collaboration with the Nazis during World War II...

. The Vichy government in exile

Government in exile

A government in exile is a political group that claims to be a country's legitimate government, but for various reasons is unable to exercise its legal power, and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile usually operate under the assumption that they will one day return to their...

ended in April 1945.

"Yesterday Strasbourg, tomorrow Saigon..."

French Far East Expeditionary Corps

The French Far East Expeditionary Corps was a colonial expeditionary force of the French Union Army sent in French Indochina in 1945 during the Pacific War.-Pacific War :...

(FEFEO) that sailed to French Indochina

French Indochina

French Indochina was part of the French colonial empire in southeast Asia. A federation of the three Vietnamese regions, Tonkin , Annam , and Cochinchina , as well as Cambodia, was formed in 1887....

then occupied by the Japanese

Second French Indochina Campaign

The Second French Indochina Campaign, also known as the Japanese coup of March 1945, was a Japanese military operation in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, then a French colony and known as French Indochina, during the final months of the Second World War. Vietnam was not a real colony at this time. The...

in 1945.

FEFEO recruiting posters depicted a Sherman tank painted with the cross of Lorraine

Cross of Lorraine

The Cross of Lorraine is originally a heraldic cross. The two-barred cross consists of a vertical line crossed by two smaller horizontal bars. In the ancient version, both bars were of the same length. In 20th century use it is "graded" with the upper bar being the shortest...

with the caption "Yesterday Strasbourg

Strasbourg