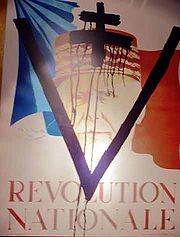

Révolution nationale

Encyclopedia

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

name under which the Vichy regime ("the French state") established by Marshal Philippe Pétain

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

in July 1940 presented its program. Pétain's regime was characterized by its anti-parliamentarism and rejection of the constitutional separation of powers

Separation of powers

The separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle, is a model for the governance of a state. The model was first developed in ancient Greece and came into widespread use by the Roman Republic as part of the unmodified Constitution of the Roman Republic...

, personality cult, xenophobia

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is defined as "an unreasonable fear of foreigners or strangers or of that which is foreign or strange". It comes from the Greek words ξένος , meaning "stranger," "foreigner" and φόβος , meaning "fear."...

and state anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

, promotion of traditional values

Tradition

A tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

and rejection of modernity

Modernity

Modernity typically refers to a post-traditional, post-medieval historical period, one marked by the move from feudalism toward capitalism, industrialization, secularization, rationalization, the nation-state and its constituent institutions and forms of surveillance...

, and finally corporatism

Corporatism

Corporatism, also known as corporativism, is a system of economic, political, or social organization that involves association of the people of society into corporate groups, such as agricultural, business, ethnic, labor, military, patronage, or scientific affiliations, on the basis of common...

and opposition to class conflict

Class conflict

Class conflict is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to competing socioeconomic interests between people of different classes....

. Despite its name, the regime was more reactionary than revolutionary, opposing most changes since the 1789 French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

.

As soon as it had been established, Pétain's government took measures against the "undesirables": Jews, métèques

Metic

In ancient Greece, the term metic referred to a resident alien, one who did not have citizen rights in his or her Greek city-state of residence....

(immigrants), Freemasons

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

, Communists—inspired by Charles Maurras

Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras was a French author, poet, and critic. He was a leader and principal thinker of Action Française, a political movement that was monarchist, anti-parliamentarist, and counter-revolutionary. Maurras' ideas greatly influenced National Catholicism and "nationalisme...

' conception of the "Anti-France", or "internal foreigners", which Maurras defined as the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners" — but also Gypsies, homosexuals, and, in a general way, any left-wing activist. Vichy imitated the racial policies of the Third Reich and also engaged in natalist

Natalism

Natalism is a belief that promotes human reproduction. The term is taken from the Latin adjective form for "birth", natalis. Natalism promotes child-bearing and glorifies parenthood...

policies aimed at reviving the "French race" (including a sport policy), although these policies never went as far as the eugenics program implemented by the Nazi

Nazi eugenics

Nazi eugenics were Nazi Germany's racially-based social policies that placed the improvement of the Aryan race through eugenics at the center of their concerns...

s.

Ideology

The ideology of the "French state" (Vichy France) was an adaptation of the ideas of the French far-right (monarchismMonarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the establishment, preservation, or restoration of a monarchy as a form of government in a nation. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government out of principle, independent from the person, the Monarch.In this system, the Monarch may be the...

, Charles Maurras

Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras was a French author, poet, and critic. He was a leader and principal thinker of Action Française, a political movement that was monarchist, anti-parliamentarist, and counter-revolutionary. Maurras' ideas greatly influenced National Catholicism and "nationalisme...

' integralism

Integralism

Integralism, or Integral nationalism, is an ideology according to which a nation is an organic unity. Integralism defends social differentiation and hierarchy with co-operation between social classes, transcending conflict between social and economic groups...

, etc.) to and by a "crisis" government, born out of the defeat of France

Battle of France

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

. It included:

- The conflation of legislative and executiveSeparation of powersThe separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle, is a model for the governance of a state. The model was first developed in ancient Greece and came into widespread use by the Roman Republic as part of the unmodified Constitution of the Roman Republic...

powers. The Constitutional Acts drafted by Pétain on 11 July 1940 attributed him "more powers than to Louis XIVLouis XIV of FranceLouis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

" (according to a quote by Pétain himself, brought by his civil head of staff, H. Du Moulin de Labarthète), including that of drafting a new ConstitutionConstitution of FranceThe current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, and replaced that of the Fourth Republic dating from 1946. Charles de Gaulle was the main driving force in introducing the new constitution and inaugurating the Fifth...

. - Anti-parliamentarism and rejection of the multi-party systemMulti-party systemA multi-party system is a system in which multiple political parties have the capacity to gain control of government separately or in coalition, e.g.The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition in the United Kingdom formed in 2010. The effective number of parties in a multi-party system is normally...

. - Personality cult. Marshall Pétain's portrait was omnipresent, printed on money, stamps, walls or represented in sculptures. A song to his glory, Maréchal, nous voilà !Maréchal, nous voilà !"Maréchal, nous voilà !" is a French song dedicated to Marshal Philippe Pétain. Lyrics were composed by André Montagnard , and music was attributed to André Montagnard and Charles Courtioux...

, became the un-official national anthem. Obedience to the leader and to the hierarchy was exalted. - CorporatismCorporatismCorporatism, also known as corporativism, is a system of economic, political, or social organization that involves association of the people of society into corporate groups, such as agricultural, business, ethnic, labor, military, patronage, or scientific affiliations, on the basis of common...

, with the establishment of a Labour Charter (suppression of trade-unions replaced by corporations organized by sectors, suppression of the right to strike). - Stigmatization of those seen as responsible for the military defeatBattle of FranceIn the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

, expressed in particular during the Riom TrialRiom TrialThe Riom Trial was an attempt by the Vichy France regime, headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain, to prove that the leaders of the French Third Republic had been responsible for France's defeat by Germany in 1940...

(1942–43): the Third RepublicFrench Third RepublicThe French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

, in particular the Popular FrontPopular Front (France)The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements, including the French Communist Party , the French Section of the Workers' International and the Radical and Socialist Party, during the interwar period...

(despite the fact that Léon BlumLéon BlumAndré Léon Blum was a French politician, usually identified with the moderate left, and three times the Prime Minister of France.-First political experiences:...

's left-wing government prepared France for the war by launching a new military effort), Communists, Jews, etc. The defendants of the Riom Trial included Léon Blum, Édouard DaladierÉdouard DaladierÉdouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

, Paul ReynaudPaul ReynaudPaul Reynaud was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany. He was the penultimate Prime Minister of the Third Republic and vice-president of the Democratic Republican Alliance center-right...

, Georges MandelGeorges MandelGeorges Mandel was a French politician, journalist, and French Resistance leader.-Biography:Born Louis George Rothschild in Chatou, Yvelines, was the son of a tailor...

and Maurice GamelinMaurice GamelinMaurice Gustave Gamelin was a French general. Gamelin is best remembered for his unsuccessful command of the French military in 1940 during the Battle of France and his steadfast defense of republican values....

. - State anti-SemitismAnti-SemitismAntisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

. Jews, national or not, were excluded from the Nation, and prohibited from working in public services. The first Statute on JewsStatute on JewsThe Statute on Jews was discriminatory legislation against French Jews passed on October 3, 1940 by the Vichy Regime, grouping them as a lower class and depriving them of citizenship before rounding them up at Drancy internment camp then taking them to be exterminated in concentration camps...

was promulgated on 3 October 1940. Thousands of naturalizedNaturalizationNaturalization is the acquisition of citizenship and nationality by somebody who was not a citizen of that country at the time of birth....

Jews were deprived of their citizenship, while all Jews were forced to wear a yellow badgeYellow badgeThe yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

. A numerus claususNumerus claususNumerus clausus is one of many methods used to limit the number of students who may study at a university. In many cases, the goal of the numerus clausus is simply to limit the number of students to the maximum feasible in some particularly sought-after areas of studies.However, in some cases,...

drastically limited their presence at the University, among physicians, lawyers, film-makers, bankers or small trade. Soon the list of off-limits works was greatly increased. In less than a year, more than half of the Jewish population in FranceHistory of the Jews in FranceThe history of the Jews of France dates back over 2,000 years. In the early Middle Ages, France was a center of Jewish learning, but persecution increased as the Middle Ages wore on...

was deprived of any means of subsistence. Foreign Jews first, then all Jews were at first detained in concentration camps in France, before being deported to Drancy internment campDrancy internment campThe Drancy internment camp of Paris, France, was used to hold Jews who were later deported to the extermination camps. 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy, of whom 63,000 were murdered including 6,000 children...

where they were then sent to Nazi concentration campsNazi concentration campsNazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

. - "OrganicismOrganicismOrganicism is a philosophical orientation that asserts that reality is best understood as an organic whole. By definition it is close to holism. Plato, Hobbes or Constantin Brunner are examples of such philosophical thought....

" and rejection of class conflictClass conflictClass conflict is the tension or antagonism which exists in society due to competing socioeconomic interests between people of different classes....

. - Promotion of traditional valuesTraditionA tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

. The Republican moto of "Liberté, Egalité, FraternitéLiberté, égalité, fraternitéLiberté, égalité, fraternité, French for "Liberty, equality, fraternity ", is the national motto of France, and is a typical example of a tripartite motto. Although it finds its origins in the French Revolution, it was then only one motto among others and was not institutionalized until the Third...

" replaced by the motto of "Labour, Family, Fatherland." (Travail, Famille, Patrie). - Rejection of cultural modernismModernismModernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society...

and of intellectual and urban elites. Policy of "return to the earth" (which convinced no more than 1,500 persons to return to the fields).

Currents

The Révolution nationale particularly attracted three groups of persons. The Pétainistes gathered those who supported the personal figure of Marshall Pétain, considered at that time a war hero of the Battle of VerdunBattle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

. The Collaborateurs include those who collaborated with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

or advocated collaboration, but who are considered more moderate, or more opportunistic, than the Collaborationistes, advocates of a French fascism. Those who supported the ideology of the "National Revolution" rather than the person of Pétain himself could be divided, in general, in three groups, composed of the counter-revolutionary reactionaries, the supporters of a French fascism and the reformers who saw in the new regime in opportunity to modernize the state apparatus. The last current would include opportunists such as the journalist Jean Luchaire

Jean Luchaire

Jean Luchaire was a French journalist and politician who founded the weekly Notre Temps in 1927 and the Collaborationist evening daily Les Nouveaux Temps in 1940. Luchaire supported the Vichy regime's Révolution nationale.Born in Siena, Italy, he was a grand nephew of historian Achille Luchaire...

who saw in the new regime career opportunities.

- The "ReactionariesReactionaryThe term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

", in the strict sense of the word: all those who dreamt of a return to "before", before 1936 (and the Popular FrontPopular Front (France)The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements, including the French Communist Party , the French Section of the Workers' International and the Radical and Socialist Party, during the interwar period...

); before 1870 and the Third RepublicFrench Third RepublicThe French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

; before 1789 and the French RevolutionFrench RevolutionThe French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

. Those were part of the counter-revolutionary branch of the French far right, the oldest one, composed of Legitimists, monarchist members of the Action françaiseAction FrançaiseThe Action Française , founded in 1898, is a French Monarchist counter-revolutionary movement and periodical founded by Maurice Pujo and Henri Vaugeois and whose principal ideologist was Charles Maurras...

(AF), etc. They were well represented by Charles MaurrasCharles MaurrasCharles-Marie-Photius Maurras was a French author, poet, and critic. He was a leader and principal thinker of Action Française, a political movement that was monarchist, anti-parliamentarist, and counter-revolutionary. Maurras' ideas greatly influenced National Catholicism and "nationalisme...

' exclamation at the dissolving of the Republic: "What a divine surprise!" But the Vichy regime also received support from large sectors of the liberal OrleanistOrléanistThe Orléanists were a French right-wing/center-right party which arose out of the French Revolution. It governed France 1830-1848 in the "July Monarchy" of king Louis Philippe. It is generally seen as a transitional period dominated by the bourgeoisie and the conservative Orleanist doctrine in...

s, in particular from its mouthpiece, Le TempsLe Temps (Paris)Le Temps was one of Paris's most important daily newspapers from April 25, 1861 to November 30, 1942.Founded in 1861 by Edmund Chojecki and Auguste Nefftzer, Le Temps was under Nefftzer's direction for ten years, when Adrien Hébrard took his place...

newspaper .

- The supporters of a "French fascism", which opposed specific traditionalist aspects such as clericalismClericalismClericalism is the application of the formal, church-based, leadership or opinion of ordained clergy in matters of either the church or broader political and sociocultural import...

or "naive scoutingScoutingScouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement with the stated aim of supporting young people in their physical, mental and spiritual development, that they may play constructive roles in society....

", but still thought the Révolution nationale prepared for a "re-birth" of French society. These formed the most stringent Collaborationists (collaborationistes, distinct of collaborateurs who are seen as more moderate or more opportunist). Those included the supporters of Marcel DéatMarcel DéatMarcel Déat was a French Socialist until 1933, when he initiated a spin-off from the French Section of the Workers' International along with other right-wing 'Neosocialists'. He then founded the collaborationist National Popular Rally during the Vichy regime...

's Rassemblement national populaire (RNP), Jacques DoriotJacques DoriotJacques Doriot was a French politician prior to and during World War II. He began as a Communist but then turned Fascist.-Early life and politics:...

's Parti Populaire FrançaisParti Populaire FrançaisThe Parti Populaire Français was a fascist political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II...

(PPF), Joseph DarnandJoseph DarnandJoseph Darnand was a French soldier and later a leader of the Vichy French collaborators with Nazi Germany....

's Service d'ordre légionnaireService d'ordre légionnaireThe Service d'ordre légionnaire was a collaborationist militia created by Joseph Darnand, a far right veteran from the First World War...

(SOL) militia, Marcel BucardMarcel BucardMarcel Bucard was a French Fascist politician.Early career=...

's Mouvement FrancisteMouvement FrancisteThe Mouvement Franciste was a French Fascist and Antisemitic league created by Marcel Bucard in September 1933; it edited the newspaper Le Francisme. Mouvement Franciste reached of membership of 10,000, and was financed by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini...

(originally funded by Benito MussoliniBenito MussoliniBenito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

), members of the CagouleLa CagouleLa Cagoule , officially called Comité secret d'action révolutionnaire , was a violent French fascist-leaning and anti-communist group, active in the 1930s, and designed to attempt the overthrow of the French Third Republic...

terrorist group, funded by Eugène SchuellerEugène SchuellerEugène Schueller was the founder of L'Oréal, the world's leading company in cosmetics and beauty.- Career with L'Oréal :...

(the founder of L'OréalL'OréalThe L'Oréal Group is the world's largest cosmetics and beauty company. With its registered office in Paris and head office in the Paris suburb of Clichy, Hauts-de-Seine, France, it has developed activities in the field of cosmetics...

cosmetic group), the writers Robert BrasillachRobert BrasillachRobert Brasillach was a French author and journalist. Brasillach is best known as the editor of Je suis partout, a nationalist newspaper which came to advocate various fascist movements and supported Jacques Doriot...

, Louis-Ferdinand CélineLouis-Ferdinand CélineLouis-Ferdinand Céline was the pen name of French writer and physician Louis-Ferdinand Destouches . Céline was chosen after his grandmother's first name. He is considered one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, developing a new style of writing that modernized both French and...

or Pierre Drieu La RochellePierre Drieu La RochellePierre Eugène Drieu La Rochelle was a French writer of novels, short stories and political essays, who lived and died in Paris...

, Philippe HenriotPhilippe HenriotPhilippe Henriot was a French politician.Moving to the far right after beginnings in Roman Catholic conservatism in the Republican Federation, Henriot was elected to the Third Republic's Chamber of Deputies for the Gironde département in 1932 and 1936...

at Radio ParisRadio ParisRadio Paris was a French radio broadcasting company best known for its Axis propaganda broadcasts in Vichy France during World War II.Radio Paris evolved from the first private radio station in France, called Radiola, founded by pioneering French engineer Émile Girardeau in 1922...

, etc.

- The Reformers, who were looking for new political, social and economic policies, and formed quite an important group during the inter-war period. Those included the non-conformists of the 1930sNon-conformists of the 1930sThe Non-Conformists of the 1930s refers to a nebula of groups and individuals during the inter-war period in France which was looking for new solutions to face the political, economical and social crisis. The name was coined in 1969 by the historian Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle to describe a...

, Christian-democrats personalistsPersonalismPersonalism is a philosophical school of thought searching to describe the uniqueness of a human person in the world of nature, specifically in relation to animals...

, neo-socialists, planistesPlanismePlanisme was an ideological current in the interwar period which advocated the use of economic plans and planification. Représentants of planisme include, in France, the groupe X-crise, and in Belgium Henri de Man...

, Young Turks of the Radical Socialist Party, technocrats (Groupe X-CriseGroupe X-CriseThe Groupe X-Crise was a French technocratic movement created in 1931 as an aftermath of the 1929 Wall Street stock market crash and the Great Depression. Formed by former students of the École Polytechnique , it advocated planisme, or economic planification, as opposed to the then dominant...

), etc. All of these circles would also provide recruits to the ResistanceFrench ResistanceThe French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

. Most of them were not ideologically anti-democrats, but claimed to take advantage of the new conditions set by the Vichy regime—they also included plain opportunistsOpportunism-General definition:Opportunism is the conscious policy and practice of taking selfish advantage of circumstances, with little regard for principles. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term can be applied to individuals, groups,...

willing to make a quick career. They presented various and contradictory solutions: communalismCommunalismCommunalism is a term with three distinct meanings according to the Random House Unabridged Dictionary'.'These include "a theory of government or a system of government in which independent communes participate in a federation". "the principles and practice of communal ownership"...

, cooperativeCooperativeA cooperative is a business organization owned and operated by a group of individuals for their mutual benefit...

s or corporations, "return to the earth", planned economyPlanned economyA planned economy is an economic system in which decisions regarding production and investment are embodied in a plan formulated by a central authority, usually by a government agency...

, technocracy rule, etc. Some examples include René Belin, Minister of Production and Labour, Lucien RomierLucien RomierLucien Romier was a French journalist and politician.After studying at the École des Chartes, where he wrote a thesis on Jacques d'Albon de Saint-André, he was a member of the French School in Rome....

, who also became Minister of Pétain, the civil servant Gérard Bardet, X-Crise member Pierre PucheuPierre PucheuPierre Firmin Pucheu was a French industrialist, fascist and member of the Vichy government.-Early years:...

, François LehideuxFrançois LehideuxFrançois Lehideux was a French industrialist and member of the Vichy government.-Car industry:...

, Yves Bouthillier, Jacques BarnaudJacques BarnaudJacques Barnaud was a French banker, businessman and member of the collaborationist Vichy regime during the Second World War....

, or the École des cadres d'Uriage, which would form the basis after the war of the elite school École nationale d'administrationÉcole nationale d'administrationThe École Nationale d'Administration , one of the most prestigious of French graduate schools , was created in 1945 by Charles de Gaulle to democratise access to the senior civil service. It is now entrusted with the selection and initial training of senior French officials...

(ENA).

Evolution of the regime

From July 1940 to 1942, the Révolution nationale was strongly promoted by the traditionalist and technocratic Vichy government. When in May 1942 Pierre LavalPierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

(a former socialist and republican) returned as the head of government, the Révolution nationale was no longer promoted but fell into oblivion and collaboration was emphasized.

Eugenics

In 1941, Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

winner Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charles A. Lindbergh opening the way to organ transplantation...

, who had been an early proponent of eugenics

Eugenics

Eugenics is the "applied science or the bio-social movement which advocates the use of practices aimed at improving the genetic composition of a population", usually referring to human populations. The origins of the concept of eugenics began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance,...

and euthanasia

Euthanasia

Euthanasia refers to the practice of intentionally ending a life in order to relieve pain and suffering....

and was a member of Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot was a French politician prior to and during World War II. He began as a Communist but then turned Fascist.-Early life and politics:...

's French Popular Party (PPF), went on to advocate for the creation of the Fondation Française pour l’Etude des Problèmes Humains (French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems), using connections to the Pétain cabinet (specifically, French industrial physicians André Gros and Jacques Ménétrier). Charged of the "study, under all of its aspects, of measures aimed at safeguarding, improving and developing the French population

Demographics of France

This article is about the demographic features of the population of France, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects....

in all of its activities," the Foundation was created by decree

Decree

A decree is a rule of law issued by a head of state , according to certain procedures . It has the force of law...

of the Vichy regime in 1941, and Carrel appointed as 'regent'.

The sport policy

Vichy's policy concerning sports found its origins in Georges Hébert's (1875–1957) conception, who denounced professional and spectacular competition, and like Pierre de CoubertinPierre de Coubertin

Pierre de Frédy, Baron de Coubertin was a French educationalist and historian, founder of the International Olympic Committee, and is considered the father of the modern Olympic Games...

, founder of the Olympic Games

Olympic Games

The Olympic Games is a major international event featuring summer and winter sports, in which thousands of athletes participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition where more than 200 nations participate...

was a supporter of amateurism. Vichy's sport policy followed the moral aim of "rebuilding the nation", was opposed to Léo Lagrange

Léo Lagrange

Léo Lagrange was a French Under-Secretary of State for Sports and for the Organisation of Leisure during the Popular Front...

's sport policy during the Popular Front and, but specifically opposed to professional sport imported from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. They also were used to engrain the youth in various associations and federations, as done by the Hitler Youth

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party. It existed from 1922 to 1945. The HJ was the second oldest paramilitary Nazi group, founded one year after its adult counterpart, the Sturmabteilung...

or Mussolini's Balilla

Balilla

Balilla was the nickname of Giovan Battista Perasso, a Genoese boy who started the revolt of 1746 against the Habsburg forces that occupied the city in the War of the Austrian Succession by throwing a stone on an Austrian official....

.

On 7 August 1940 a Commissariat Général à l’Education Générale et Sportive (General Commissionneer to General and Sport Education) was created. Three men in particular headed this policy:

- Jean YbarnegarayJean YbarnegarayMichel Albert Jean Joseph Ybarnegaray was a French politician and founder of the International Association for Basque Pelota....

, president and founder of the French and International Federations of Basque pelota, deputy and member of François de la RocqueFrançois de la RocqueFrançois de La Rocque was leader of the French right-wing league named the Croix de Feu from 1930–1936, before forming the more moderate Parti Social Français , seen as a precursor of Gaullism.- Early life :François de La Rocque was born on 6 October 1885 in Lorient, Brittany, the third son to a...

's Parti Social Français (PSF). Ybarnegaray was first nominated State minister in May 1940, then State secretary from June to September 1940. - Jean BorotraJean BorotraJean Robert Borotra was a French champion tennis player. He was one of the famous "Four Musketeers" from his country who dominated tennis in the late 1920s and early 1930s.-Career:...

, former international tennis player (member of "The Four MusketeersThe Four MusketeersThe Four Musketeers, after a popular 1920s film adaptation of Alexandre Dumas' classic, were French tennis players who dominated the game in the second half of the 1920s and early 1930s, winning 20 Grand Slam titles and 23 Grand Slam doubles...

") and also a PSF member, 1st General Commissioner to Sports from August 1940 to April 1942. - Colonel Joseph Pascot, former rugby champion, director of sports under Borotra and then second General Commissioner to Sports from April 1942 to July 1944.

As soon as October 1940, the two General Commissioners prohibited professionalism in two federations (tennis and wrestling), while permitting a three year delay for four others federations (Football, Cycling, Boxing and Basque Pelota). They prohibited competitions for women in cycling or Football. Furthermore, they prohibited or spoiled by seizing the assets of at least four uni-sport federations, Rugby League

Rugby league

Rugby league football, usually called rugby league, is a full contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular grass field. One of the two codes of rugby football, it originated in England in 1895 by a split from Rugby Football Union over paying players...

, Table Tennis

Table tennis

Table tennis, also known as ping-pong, is a sport in which two or four players hit a lightweight, hollow ball back and forth using table tennis rackets. The game takes place on a hard table divided by a net...

, Jeu de paume

Jeu de paume

Jeu de paume is a ball-and-court game that originated in France. It was an indoor precursor of tennis played without racquets, though these were eventually introduced. It is a former Olympic sport, and has the oldest ongoing annual world championship in sport, first established over 250 years ago...

, Badminton

Badminton

Badminton is a racquet sport played by either two opposing players or two opposing pairs , who take positions on opposite halves of a rectangular court that is divided by a net. Players score points by striking a shuttlecock with their racquet so that it passes over the net and lands in their...

and from one multi-sport federation (the FSGT). In April 1942, they also prohibited the activities of the UFOLEP and USEP multisports' federation, also seizing their goods which were to be transferred to the "National Council of Sports."

Quotes

- "Sport well directed is moral in action" ("Le sport bien dirigé, c’est de la morale en action"), Report of E. Loisel to Jean BorotraJean BorotraJean Robert Borotra was a French champion tennis player. He was one of the famous "Four Musketeers" from his country who dominated tennis in the late 1920s and early 1930s.-Career:...

, 15 October 1940 - "I pledge on my honour to practice sports with selflessness, discipline and loyalty to improve myself and serve better my fatherland" (Sportman's pledge — « Je promets sur l’honneur de pratiquer le sport avec désintéressement, discipline et loyauté pour devenir meilleur et mieux servir ma patrie »)

- "to be strong to serve better" (IO 1941)

- "Our principle is to seize the individual everywhere. At primary school, we have him. Later on he tends to escape us. We efforce ourselves to catch up with him in all occasions. I have obtained that this discipline of EG (General Education) be imposed to students (...) We have prepared punitions in case of desertions." (« Notre principe est de saisir l’individu partout. Au primaire, nous le tenons. Plus haut il tend à s’échapper. Nous nous efforçons de le rattraper à tous les tournants. J’ai obtenu que cette discipline de l’EG soit imposée aux étudiants (…). Nous prévoyons des sanctions en cas de désertion »), Colonel Joseph Pascot, speech on 27 June 1942

See also

- Vichy FranceVichy FranceVichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

- Popular Front (France)Popular Front (France)The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements, including the French Communist Party , the French Section of the Workers' International and the Radical and Socialist Party, during the interwar period...

- History of far right movements in FranceHistory of far right movements in FranceThe far-right tradition in France finds its origins in the Third Republic with the Boulangism and the Dreyfus Affair.- The Third Republic from 1871 to 1914 :...

- History of France during the twentieth century

- World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

and Holocaust

External links

- Loi et décret 1940-42

- Sports et Politique

- Politique sportive du gouvernement de Vichy: discours et réalité

- Sport et Français pendant l'occupation

- JP Azéma: Président commission "Politique du sport et éducation physique en France pendant l'occupation."

- Exemples: Badminton, Tennis de table, Jeu de paume Interdits

- Vichy et le football