Anti-Catholicism in the United States

Encyclopedia

Strong political and theological positions hostile to the Catholic Church and its followers was prominent among Protestants in Britain

and Germany from the Protestant Reformation

onwards. Immigrants brought them to the American colonies. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the theological heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a secular variety which focused on the alleged intrigues of Catholic states which were hostile to both Marxism

and Classical Liberalism

.

Historians have studied the motivations for anti-Catholicism. The basic motivations were political (the threat posed by Rome and its allies to Protestant nations) and theological. However, scholars have also speculated on the psychological motivations, usually concluding that a strong element of irrational bigotry was involved. Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.

characterized prejudice against the Catholics as "the deepest bias in the history of the American people." Conservative writer Peter Viereck

once commented that (in 1960) "Catholic baiting is the anti-Semitism of the liberals." Historian John Higham

described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".

Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritan

s and Congregationalist

s, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts

to Georgia

." Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics having any political power. Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could bring together Anglican and Puritan

clergy and laity despite their many other disagreements.

In 1642, the Colony of Virginia enacted a law prohibiting Catholic settlers. Five years later, a similar statute was enacted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony

.

In 1649 the Act of Toleration was passed, where "blasphemy and the calling of opprobrious religious names" became punishable offenses, but it was repealed in 1654 and thus outlawing Catholics once again. Puritans condemned ten Catholics to death and plundered the property of the Catholic clergy. By 1692, formerly Catholic Maryland overthrew its Government, established the Church of England

by law, and forced Catholics to pay heavy taxes towards its support. They were cut off from all participation in politics and additional laws were introduced that outlawed the mass, the sacraments, and Catholic schools.

In 1719, Rhode Island imposed civil restrictions on Catholics.

Pennsylvania became a safe haven for Catholic refugees from Maryland. William Penn had been harassed as a Quaker, and enacted a broad grant of religious toleration and civil rights to all who believed in God, regardless of their particular denomination. The threat of war between England and France brought about renewed suspicions against Catholics. However, the Quaker government in Pennsylvania refused to be coerced into violating their traditional policies.

Maryland passed an act of religious toleration in 1776.

Another result of anti-Catholicism in the English colonies was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church

, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant.

John Adams

attended a Catholic Mass in Philadelphia one day in 1774. He praised the sermon for teaching civic duty, and enjoyed the music, but ridiculed the rituals engaged in by the parishioners. In 1788, John Jay

urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce the pope and foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil," which included both the Catholic and the Anglican churches. Thomas Jefferson

, referring to Europe, wrote: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government," and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

was published. It was a great commercial success and is still circulated today by such publishers as Jack Chick

. It was discovered to be a fabrication shortly after publication.

in the Book of Revelation

.

In his best-selling book of fiction, A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur's Court

(1889), author Mark Twain

indicates his hostility to the Catholic Church. He admitted that he had "...been educated to enmity toward everything that is Catholic."

and Horace Bushnell

, attacked the Catholic Church as not only theologically unsound but an enemy of republican values. Some scholars view the anti-Catholic rhetoric of Beecher and Bushnell as having contributed to anti-Irish and anti-Catholic pogroms.

Beecher's well-known Plea for the West (1835) urged Protestants to exclude Catholics from western settlements. The Catholic Church's official silence on the subject of slavery also garnered the enmity of northern Protestants. Intolerance became more than an attitude on 11 August 1834, when a mob set fire to an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics. This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for spreading violence and drunkenness.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore

as its presidential candidate in 1856.

Catholic schools began in the United States as a matter of religious and ethnic pride and as a way to insulate Catholic youth from the influence of Protestant teachers and contact with non-Catholic students.

Catholic schools began in the United States as a matter of religious and ethnic pride and as a way to insulate Catholic youth from the influence of Protestant teachers and contact with non-Catholic students.

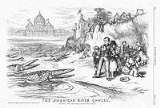

In the 1869 the religious issue in New York City escalated when Tammany Hall

, with its large Catholic base, sought and obtained $1.5 million in state money for Catholic schools. Thomas Nast

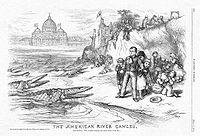

's cartoon The American River Ganges (above) shows Catholic Bishops, directed by the Vatican, as crocodiles attacking American schoolchildren.

Republican Senator James G. Blaine

of Maine proposed an amendment to the Constitution in 1874 that provided: "No money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public source, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or land so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations." The amendment was defeated in 1875 but would be used as a model for so-called "Blaine Amendments" incorporated into 34 state constitutions over the next three decades.

In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant

supported the Blaine Amendment

-- a Constitutional amendment that would mandate free public schools and prohibit the use of public funds for "sectarian" schools. Grant feared a future with "patriotism and intelligence on one side and superstition, ambition and greed on the other" and called for public schools that would be "unmixed with atheistic, pagan or sectarian teaching."

These "Blaine amendments" prohibited the use of public funds to fund parochial schools.

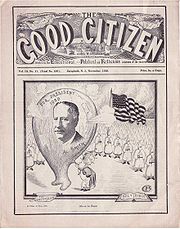

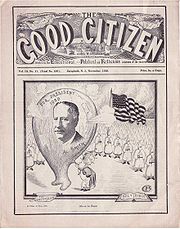

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics, including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. The Catholics responded to such prejudices by repeatedly asserting their rights as American citizens and by arguing that they, not the nativists (anti-Catholics), were true patriots since they believed in the right to freedom of religion.

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics, including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. The Catholics responded to such prejudices by repeatedly asserting their rights as American citizens and by arguing that they, not the nativists (anti-Catholics), were true patriots since they believed in the right to freedom of religion.

With the resurrection of the Ku Klux Klan

(KKK) in 1915, anti-Catholic rhetoric intensified. The Catholic Church of the Little Flower

was first built in 1925 in Royal Oak, Michigan

, a largely Protestant area. Two weeks after it opened, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of the church.

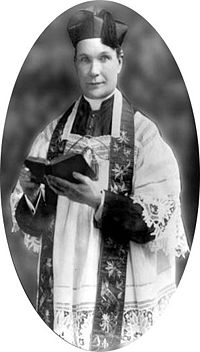

On August 11, 1921, Father James Coyle

On August 11, 1921, Father James Coyle

was fatally shot while sitting on his rectory porch in Birmingham, Alabama

. Several witnesses identified the shooter as Rev. E. R. Stephenson

, a Southern Methodist Episcopal

minister and a member of the Ku Klux Klan

. There were many witnesses. The murder occurred just hours after Coyle had performed a wedding mass between Stephenson's daughter, Ruth, and Pedro Gussman, a Puerto Rican

immigrant whom she had met while he was working on Stephenson's house five years earlier. Gussman had also been a customer of Stephenson's barber shop. Several months before the wedding, Ruth had enraged her father by converting to Roman Catholicism.

In the aftermath, Stephenson was arrested and charged with Father Coyle's murder. The Ku Klux Klan

paid for the defense team. Of Stephenson's five lawyers, four were Klan members. The case was assigned to the Alabama courtroom of Judge William E. Fort, a Klansman. Hugo Black

, a future Justice of the Supreme Court

defended Stephenson.

The defense team took the unusual step of entering a dual plea of "not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity", essentially arguing both that the shooting was in self defense, and that at the time of the shooting Stephenson had been suffering from temporary insanity. Stephenson was acquitted by one vote of the jury. One of Stephenson's attorneys responded to the prosecution's assertion that Gussman was of "proud Castilian descent" by saying "he has descended a long way".

Failing internally in the Mid-West, the KKK failed to carry its own power base in the "solid south", which voted for the Catholic Al Smith in 1928, opposed by the Klan. Its power was dissipated and, by 1930, the Klan had fallen under the control of lower class white Protestants who lacked the massive popular support base previously once enjoyed.

passed an initiative

amending Oregon Law

Section 5259, the Compulsory Education Act. The law unofficially became known as the Oregon School Law. The citizens' initiative was primarily aimed at eliminating parochial school

s, including Catholic schools. The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters

(1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that that has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

In 1928, Al Smith

In 1928, Al Smith

became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party's nomination for President, and his religion became an issue during the campaign

. His nomination made anti-Catholicism a rallying point especially for Lutheran and Baptist ministers. They warned that national autonomy would be threatened because Smith would be listening not to the American people but to secret orders from the pope. There were rumors the pope would move to the United States to control his new realm.

Across the country, and especially in strongholds of the Lutheran, Baptist and Fundamentalist churches, Protestant ministers spoke out. They seldom endorsed Republican Herbert Hoover

, who was a Quaker. More often they alleged Smith was unacceptable. A survey of 8,500 Southern Methodist Church

ministers found only four who publicly supported Smith. Many Americans who sincerely rejected bigotry and the Klan justified their opposition to Smith because, they believed the Catholic Church was an "unAmerican" and "alien culture" that opposed freedom and democracy. The National Lutheran Editors' and Managers' Association opposed Smith's election in a manifesto written by Dr. Clarence Reinhold Tappert. It warned about, "the peculiar relation in which a faithful Catholic stands and the absolute allegiance he owes to a 'foreign sovereign' who does not only 'claim' supremacy also in secular affairs as a matter of principle and theory but who, time and again, has endeavored to put this claim into practical operation." The Catholic Church, the manifesto asserted, was hostile to American principles of separation of church and state and of religious toleration. Prohibition had widespread support in rural Protestant areas, and Smith's wet position, as well as his long-time sponsorship by Tammany Hall

compounded his difficulties there. He was weakest in the border states; the day after Smith gave a talk pleaded for brotherhood in Oklahoma City, the same auditorium was jammed for an evangelist who lecture on "Al Smith and the Forces of Hell." Smith picked Senator Joe T. Robinson, a prominent Arkansas Senator as his running mate. When the pro-Smith Democrats raised the race issue against the Republicans they were able to contain their losses in the Black Belt

(areas with black majorities but where only whites voted) so Smith carried the Deep South—the area long identified with anti-Catholicism. Efforts by Senator Tom Heflin to recycle his long-standing attacks on the pope failed in Alabama. Smith's strong anti-Klan position resonated across the country with voters who thought the KKK was a real threat to democracy. Smith split the South, carrying the Deep South while losing the periphery. After 1928 the Solid South

returned to the Democratic fold. One long-term result was the surge in Democratic voting in the large cities, as ethnic Catholics went to the polls to defend their religious culture, often bringing their women to the polls for the first time. The nation's twelve largest cities gave pluralities of 1.6 million to the GOP in 1920, and 1.3 million in 1924; now they went for Smith by a whisker-thin 38,000 votes, while everywhere else was for Hoover. The surge proved permanent. as Catholics comprised a major portion of the New Deal Coalition

that Franklin D. Roosevelt

assembled and which dominated national elections for decades.

In 1949, Paul Blanshard

wrote in his bestselling book American Freedom and Catholic Power

that America had a "Catholic Problem." He stated that the Church was an "undemocratic system of alien control" in which the lay were chained by the "absolute rule of the clergy." In 1951, in Communism, Democracy, and Catholic Power, he compared Rome with Moscow as "two alien and undemocratic centers," including "thought control."

A key factor that affected the vote for and against John F. Kennedy

in his 1960 campaign for the presidency of the United States was his Catholic religion. Legs, who had mostly voted for Republican Dwight Eisenhower, now gave Kennedy from 75 to 80 percent of their vote. Some Protestants, such as Norman Vincent Peale

, still feared the Pope would be giving orders to a Kennedy White House. To allay such fears, Kennedy kept his distance from church officials and in a highly publicized confrontation told the Protestant ministers of the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the Church does not speak for me." He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Church officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy counterattacked by suggesting that it was bigotry to relegate one-quarter of all Americans to second-class citizenship just because they were Catholic. In the final count, the additions and subtractions to Kennedy's vote because of religion probably canceled out. He won a close election; The New York Times

reported a “narrow consensus” among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a result of his Catholicism, as Catholics flocked to Kennedy to demonstrate their group solidarity in demanding political equality.

Starting in 1993, members of Historic Adventist splinter groups paid to have anti-Catholic billboards that called the Pope the Antichrist placed in various cities on the West Coast, including along Interstate 5

from Portland to Medford, Oregon, and in Albuquerque, New Mexico. One such group took out an anti-Catholic ad on Easter Sunday in The Oregonian

, in 2000, as well as in newspapers in Coos Bay, Oregon and in Longview and Vancouver, Washington. Mainstream Seventh-day Adventists

denounced the advertisements. The contract for the last of the billboards in Oregon ran out in 2002.

Philip Jenkins

, an Episcopalian historian, maintains that some who otherwise avoid offending members of racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups have no reservations about venting their hatred of Catholics.

In May 2006, a Gallup poll found 57% of Americans had a favorable view of the Catholic faith, while 30% of Americans had an unfavorable view. The Catholic Church's doctrines, and the priest sex abuse scandal were top issues for those who disapproved. "Greed", Roman Catholicism's view on homosexuality, and the celibate priesthood were low on the list of grievances for those who held an unfavorable view of Catholicism. While Protestants and Catholics themselves had a majority with a favorable view, those who are not Christian or are irreligious had a majority with an unfavorable view. In part, this represented a negative view toward all Christianity.

In April 2008, Gallup found that the number of Americans saying they had a positive view of U.S. Catholics had shrunk to 45% with 13% reporting a negative opinion. A substantial proportion of Americans, 41%, said their view of Catholics was neutral, while 2% of Americans indicated that they had a "very negative" view of Roman Catholics. However, with a net positive opinion of 32%, sentiment towards Catholics was more positive than that for both evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, who received net-positive opinions of 16 and 10% respectively. Gallup reported that Methodists and Baptists were viewed more positively than Catholics, as were Jews.

and LGBT

activists, criticize the Catholic Church for its policies on issues relating to human sexuality, contraception and abortion.

On January 30, 2007, John Edwards' presidential campaign

hired Amanda Marcotte

as blogmaster. The Catholic League

, which is not an official organ of the Catholic Church, took offense at her obscenity- and profanity-laced invective against Catholic doctrine and "satiric" rants against Catholic leaders, including some of her earlier writings, where she described sexual activity of the Holy Spirit and claimed that the Church sought to "justify [its] misogyny with [...] ancient mythology." The Catholic League publicly demanded that the Edwards campaign terminate Marcotte's appointment. Marcotte subsequently resigned, citing "sexually violent, threatening e-mails" she had received as a result of the controversy.

Some LGBT

activists have had a stormy relationship with the Catholic Church. In 1989 members of ACT UP and WHAM! disrupted a Sunday Mass at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

to protest the Church’s position on homosexuality

, safer sex education

and the use of condoms. One hundred eleven protesters were arrested outside the Cathedral, and at least one protester inside threw used condoms at a Church altar and desecrated

the Eucharist

during Mass. Protests against Proposition 8 supporters

at times threatened Catholic churches or organizations. Graffiti and swastikas were painted on Most Holy Redeemer Church, San Francisco

, A printing plant of the Knights of Columbus

, a Catholic organization that funded "Yes on 8", received threatening envelopes containing a white powder.

He argues that, despite this fascination with the Catholic Church, the entertainment industry also holds contempt for the Church. "It is as if producers, directors, playwrights and filmmakers feel obliged to establish their intellectual bona fides by trumpeting their differences with the institution that holds them in such thrall."

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

and Germany from the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

onwards. Immigrants brought them to the American colonies. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the theological heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a secular variety which focused on the alleged intrigues of Catholic states which were hostile to both Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

and Classical Liberalism

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is the philosophy committed to the ideal of limited government, constitutionalism, rule of law, due process, and liberty of individuals including freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly, and free markets....

.

Historians have studied the motivations for anti-Catholicism. The basic motivations were political (the threat posed by Rome and its allies to Protestant nations) and theological. However, scholars have also speculated on the psychological motivations, usually concluding that a strong element of irrational bigotry was involved. Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger, Sr. was an American historian. His son, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. was also a noted historian.-Life and career:...

characterized prejudice against the Catholics as "the deepest bias in the history of the American people." Conservative writer Peter Viereck

Peter Viereck

Peter Robert Edwin Viereck , was an American poet and political thinker, as well as a professor of history at Mount Holyoke College for five decades.-Background:...

once commented that (in 1960) "Catholic baiting is the anti-Semitism of the liberals." Historian John Higham

John Higham

John William Higham was an American historian, scholar of American culture and specialist on issues of ethnicity.-Life and career:...

described anti-Catholicism as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".

Origins

American Anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Reformation. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the papacy in particular. These positions were held by most Protestant spokesmen in the colonies, including those from Calvinist, Anglican and Lutheran traditions.Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s and Congregationalist

Congregational church

Congregational churches are Protestant Christian churches practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs....

s, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

to Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

." Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics having any political power. Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could bring together Anglican and Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

clergy and laity despite their many other disagreements.

In 1642, the Colony of Virginia enacted a law prohibiting Catholic settlers. Five years later, a similar statute was enacted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

.

In 1649 the Act of Toleration was passed, where "blasphemy and the calling of opprobrious religious names" became punishable offenses, but it was repealed in 1654 and thus outlawing Catholics once again. Puritans condemned ten Catholics to death and plundered the property of the Catholic clergy. By 1692, formerly Catholic Maryland overthrew its Government, established the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

by law, and forced Catholics to pay heavy taxes towards its support. They were cut off from all participation in politics and additional laws were introduced that outlawed the mass, the sacraments, and Catholic schools.

In 1719, Rhode Island imposed civil restrictions on Catholics.

Pennsylvania became a safe haven for Catholic refugees from Maryland. William Penn had been harassed as a Quaker, and enacted a broad grant of religious toleration and civil rights to all who believed in God, regardless of their particular denomination. The threat of war between England and France brought about renewed suspicions against Catholics. However, the Quaker government in Pennsylvania refused to be coerced into violating their traditional policies.

Maryland passed an act of religious toleration in 1776.

Another result of anti-Catholicism in the English colonies was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church

Episcopal Church (United States)

The Episcopal Church is a mainline Anglican Christian church found mainly in the United States , but also in Honduras, Taiwan, Colombia, Ecuador, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, the British Virgin Islands and parts of Europe...

, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant.

John Adams

John Adams

John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States...

attended a Catholic Mass in Philadelphia one day in 1774. He praised the sermon for teaching civic duty, and enjoyed the music, but ridiculed the rituals engaged in by the parishioners. In 1788, John Jay

John Jay

John Jay was an American politician, statesman, revolutionary, diplomat, a Founding Father of the United States, and the first Chief Justice of the United States ....

urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce the pope and foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil," which included both the Catholic and the Anglican churches. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

, referring to Europe, wrote: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government," and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own."

19th century

In 1836, Maria Monk's Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery in MontrealMaria Monk

Maria Monk was a Canadian woman who claimed to have been a nun who had been sexually exploited in her convent...

was published. It was a great commercial success and is still circulated today by such publishers as Jack Chick

Jack Chick

Jack Thomas Chick is an American publisher, writer, and comic book artist of fundamentalist Christian tracts and comic books...

. It was discovered to be a fabrication shortly after publication.

Immigration

Anti-Catholicism reached a peak in the mid nineteenth century when Protestant leaders became alarmed by the heavy influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Some believed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of BabylonWhore of Babylon

The Whore of Babylon or "Babylon the great" is a Christian allegorical figure of evil mentioned in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. Her full title is given as "Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth." -Symbolism:...

in the Book of Revelation

Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament. The title came into usage from the first word of the book in Koine Greek: apokalupsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation"...

.

In his best-selling book of fiction, A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court is an 1889 novel by American humorist and writer Mark Twain. The book was originally titled A Yankee in King Arthur's Court...

(1889), author Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

indicates his hostility to the Catholic Church. He admitted that he had "...been educated to enmity toward everything that is Catholic."

Nativism

In the 1830s and 1840s, prominent Protestant leaders, such as Lyman BeecherLyman Beecher

Lyman Beecher was a Presbyterian minister, American Temperance Society co-founder and leader, and the father of 13 children, many of whom were noted leaders, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Edward Beecher, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Thomas...

and Horace Bushnell

Horace Bushnell

Horace Bushnell was an American Congregational clergyman and theologian.-Life:Bushnell was a Yankee born in the village of Bantam, township of Litchfield, Connecticut. He attended Yale College where he roomed with future magazinist Nathaniel Parker Willis. Willis credited Bushnell with teaching...

, attacked the Catholic Church as not only theologically unsound but an enemy of republican values. Some scholars view the anti-Catholic rhetoric of Beecher and Bushnell as having contributed to anti-Irish and anti-Catholic pogroms.

Beecher's well-known Plea for the West (1835) urged Protestants to exclude Catholics from western settlements. The Catholic Church's official silence on the subject of slavery also garnered the enmity of northern Protestants. Intolerance became more than an attitude on 11 August 1834, when a mob set fire to an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics. This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for spreading violence and drunkenness.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore was the 13th President of the United States and the last member of the Whig Party to hold the office of president...

as its presidential candidate in 1856.

Parochial schools

In the 1869 the religious issue in New York City escalated when Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society...

, with its large Catholic base, sought and obtained $1.5 million in state money for Catholic schools. Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist who is considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon". He was the scourge of Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall machine...

's cartoon The American River Ganges (above) shows Catholic Bishops, directed by the Vatican, as crocodiles attacking American schoolchildren.

Republican Senator James G. Blaine

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine was a U.S. Representative, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, U.S. Senator from Maine, two-time Secretary of State...

of Maine proposed an amendment to the Constitution in 1874 that provided: "No money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public source, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or land so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations." The amendment was defeated in 1875 but would be used as a model for so-called "Blaine Amendments" incorporated into 34 state constitutions over the next three decades.

In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

supported the Blaine Amendment

Blaine Amendment

The term Blaine Amendment refers to either a failed federal constitutional amendment or actual constitutional provisions that exist in 38 of the 50 state constitutions in the United States both of which forbid direct government aid to educational institutions that have any religious affiliation...

-- a Constitutional amendment that would mandate free public schools and prohibit the use of public funds for "sectarian" schools. Grant feared a future with "patriotism and intelligence on one side and superstition, ambition and greed on the other" and called for public schools that would be "unmixed with atheistic, pagan or sectarian teaching."

These "Blaine amendments" prohibited the use of public funds to fund parochial schools.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Roman Catholic.1920s

With the resurrection of the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

(KKK) in 1915, anti-Catholic rhetoric intensified. The Catholic Church of the Little Flower

National Shrine of the Little Flower

National Shrine of the Little Flower Catholic Church in Royal Oak, Michigan is a well known Catholic Church and National Shrine executed in the lavish zig-zag Art Deco style. It was completed in two stages, from 1931 to 1936, and funded by the proceeds of the radio ministry of the controversial...

was first built in 1925 in Royal Oak, Michigan

Royal Oak, Michigan

Royal Oak is a city in Oakland County of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is a suburb of Detroit. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 57,236. It should not be confused with Royal Oak Charter Township, a separate community located nearby....

, a largely Protestant area. Two weeks after it opened, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of the church.

James Coyle

James Edwin Coyle was a Roman Catholic priest who was murdered in Birmingham, Alabama.-Early life:James Coyle was born in Drum, County Roscommon to Owen Coyle and his wife Margaret Durney. He attended Mungret College in Limerick and the Pontifical North American College in Rome...

was fatally shot while sitting on his rectory porch in Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham is the largest city in Alabama. The city is the county seat of Jefferson County. According to the 2010 United States Census, Birmingham had a population of 212,237. The Birmingham-Hoover Metropolitan Area, in estimate by the U.S...

. Several witnesses identified the shooter as Rev. E. R. Stephenson

E. R. Stephenson

Reverend Edwin R. Stephenson was a minister of the now extinct Methodist Episcopal Church, South and a member of the Ku Klux Klan. He shot and killed Catholic priest James Coyle in 1921 in Alabama, but was acquitted of the murder. His main lawyer was Hugo Black.Rev. Stephenson was a son of W. F....

, a Southern Methodist Episcopal

Methodist Episcopal Church, South

The Methodist Episcopal Church, South, or Methodist Episcopal Church South, was the so-called "Southern Methodist Church" resulting from the split over the issue of slavery in the Methodist Episcopal Church which had been brewing over several years until it came out into the open at a conference...

minister and a member of the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

. There were many witnesses. The murder occurred just hours after Coyle had performed a wedding mass between Stephenson's daughter, Ruth, and Pedro Gussman, a Puerto Rican

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

immigrant whom she had met while he was working on Stephenson's house five years earlier. Gussman had also been a customer of Stephenson's barber shop. Several months before the wedding, Ruth had enraged her father by converting to Roman Catholicism.

In the aftermath, Stephenson was arrested and charged with Father Coyle's murder. The Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

paid for the defense team. Of Stephenson's five lawyers, four were Klan members. The case was assigned to the Alabama courtroom of Judge William E. Fort, a Klansman. Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

, a future Justice of the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

defended Stephenson.

The defense team took the unusual step of entering a dual plea of "not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity", essentially arguing both that the shooting was in self defense, and that at the time of the shooting Stephenson had been suffering from temporary insanity. Stephenson was acquitted by one vote of the jury. One of Stephenson's attorneys responded to the prosecution's assertion that Gussman was of "proud Castilian descent" by saying "he has descended a long way".

Failing internally in the Mid-West, the KKK failed to carry its own power base in the "solid south", which voted for the Catholic Al Smith in 1928, opposed by the Klan. Its power was dissipated and, by 1930, the Klan had fallen under the control of lower class white Protestants who lacked the massive popular support base previously once enjoyed.

Supreme Court upholds parochial schools

In 1922, the voters of OregonOregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

passed an initiative

Initiative

In political science, an initiative is a means by which a petition signed by a certain minimum number of registered voters can force a public vote...

amending Oregon Law

Oregon Revised Statutes

The Oregon Revised Statutes is the codified body of statutory law governing the U.S. state of Oregon, as enacted by the Oregon Legislative Assembly, and occasionally by citizen initiative...

Section 5259, the Compulsory Education Act. The law unofficially became known as the Oregon School Law. The citizens' initiative was primarily aimed at eliminating parochial school

Parochial school

A parochial school is a school that provides religious education in addition to conventional education. In a narrower sense, a parochial school is a Christian grammar school or high school which is part of, and run by, a parish.-United Kingdom:...

s, including Catholic schools. The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters

Pierce v. Society of Sisters

Pierce v. Society of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, , was an early 20th century United States Supreme Court decision that significantly expanded coverage of the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The case has been cited as a precedent in...

(1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that that has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

1928 Presidential election

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith. , known in private and public life as Al Smith, was an American statesman who was elected the 42nd Governor of New York three times, and was the Democratic U.S. presidential candidate in 1928...

became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party's nomination for President, and his religion became an issue during the campaign

United States presidential election, 1928

The United States presidential election of 1928 pitted Republican Herbert Hoover against Democrat Al Smith. The Republicans were identified with the booming economy of the 1920s, whereas Smith, a Roman Catholic, suffered politically from Anti-Catholic prejudice, his anti-prohibitionist stance, and...

. His nomination made anti-Catholicism a rallying point especially for Lutheran and Baptist ministers. They warned that national autonomy would be threatened because Smith would be listening not to the American people but to secret orders from the pope. There were rumors the pope would move to the United States to control his new realm.

Across the country, and especially in strongholds of the Lutheran, Baptist and Fundamentalist churches, Protestant ministers spoke out. They seldom endorsed Republican Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

, who was a Quaker. More often they alleged Smith was unacceptable. A survey of 8,500 Southern Methodist Church

Southern Methodist Church

The Southern Methodist Church is a conservative Protestant Christian denomination with churches located in the southern part of the United States...

ministers found only four who publicly supported Smith. Many Americans who sincerely rejected bigotry and the Klan justified their opposition to Smith because, they believed the Catholic Church was an "unAmerican" and "alien culture" that opposed freedom and democracy. The National Lutheran Editors' and Managers' Association opposed Smith's election in a manifesto written by Dr. Clarence Reinhold Tappert. It warned about, "the peculiar relation in which a faithful Catholic stands and the absolute allegiance he owes to a 'foreign sovereign' who does not only 'claim' supremacy also in secular affairs as a matter of principle and theory but who, time and again, has endeavored to put this claim into practical operation." The Catholic Church, the manifesto asserted, was hostile to American principles of separation of church and state and of religious toleration. Prohibition had widespread support in rural Protestant areas, and Smith's wet position, as well as his long-time sponsorship by Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society...

compounded his difficulties there. He was weakest in the border states; the day after Smith gave a talk pleaded for brotherhood in Oklahoma City, the same auditorium was jammed for an evangelist who lecture on "Al Smith and the Forces of Hell." Smith picked Senator Joe T. Robinson, a prominent Arkansas Senator as his running mate. When the pro-Smith Democrats raised the race issue against the Republicans they were able to contain their losses in the Black Belt

Black Belt (U.S. region)

The Black Belt is a region of the Southern United States. Although the term originally described the prairies and dark soil of central Alabama and northeast Mississippi, it has long been used to describe a broad agricultural region in the American South characterized by a history of plantation...

(areas with black majorities but where only whites voted) so Smith carried the Deep South—the area long identified with anti-Catholicism. Efforts by Senator Tom Heflin to recycle his long-standing attacks on the pope failed in Alabama. Smith's strong anti-Klan position resonated across the country with voters who thought the KKK was a real threat to democracy. Smith split the South, carrying the Deep South while losing the periphery. After 1928 the Solid South

Solid South

Solid South is the electoral support of the Southern United States for the Democratic Party candidates for nearly a century from 1877, the end of Reconstruction, to 1964, during the middle of the Civil Rights era....

returned to the Democratic fold. One long-term result was the surge in Democratic voting in the large cities, as ethnic Catholics went to the polls to defend their religious culture, often bringing their women to the polls for the first time. The nation's twelve largest cities gave pluralities of 1.6 million to the GOP in 1920, and 1.3 million in 1924; now they went for Smith by a whisker-thin 38,000 votes, while everywhere else was for Hoover. The surge proved permanent. as Catholics comprised a major portion of the New Deal Coalition

New Deal coalition

The New Deal Coalition was the alignment of interest groups and voting blocs that supported the New Deal and voted for Democratic presidential candidates from 1932 until the late 1960s. It made the Democratic Party the majority party during that period, losing only to Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952...

that Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

assembled and which dominated national elections for decades.

Post World War II

In the aftermath of the World War II prejudices against Catholics could still be heard, but national leaders increasingly tried to build up a common front against communism and stressed the common: the ecumenical idea, the Judeo-Christian civilization and American national identity.In 1949, Paul Blanshard

Paul Blanshard

Paul Beecher Blanshard was a controversial American author, assistant editor of The Nation magazine, lawyer, socialist, secular humanist, and from 1949 an outspoken critic of Catholicism....

wrote in his bestselling book American Freedom and Catholic Power

American Freedom and Catholic Power

American Freedom and Catholic Power is an anti-Catholic book by American writer Paul Blanshard, published in 1949 by Beacon Press, which asserted that America had a "Catholic problem" in that the Church was an "undemocratic system of alien control". The book has been recognized as bigoted and...

that America had a "Catholic Problem." He stated that the Church was an "undemocratic system of alien control" in which the lay were chained by the "absolute rule of the clergy." In 1951, in Communism, Democracy, and Catholic Power, he compared Rome with Moscow as "two alien and undemocratic centers," including "thought control."

1960 election

A key factor that affected the vote for and against John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

in his 1960 campaign for the presidency of the United States was his Catholic religion. Legs, who had mostly voted for Republican Dwight Eisenhower, now gave Kennedy from 75 to 80 percent of their vote. Some Protestants, such as Norman Vincent Peale

Norman Vincent Peale

Dr. Norman Vincent Peale was a minister and author and a progenitor of the theory of "positive thinking".-Early life and education:...

, still feared the Pope would be giving orders to a Kennedy White House. To allay such fears, Kennedy kept his distance from church officials and in a highly publicized confrontation told the Protestant ministers of the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters — and the Church does not speak for me." He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Church officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy counterattacked by suggesting that it was bigotry to relegate one-quarter of all Americans to second-class citizenship just because they were Catholic. In the final count, the additions and subtractions to Kennedy's vote because of religion probably canceled out. He won a close election; The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

reported a “narrow consensus” among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a result of his Catholicism, as Catholics flocked to Kennedy to demonstrate their group solidarity in demanding political equality.

1990 - 21st century

In 1989, the New York Times warned the Catholic Bishops that if they followed the church's instructions and denied communion to politicians who advocated a pro-choice position regarding abortion they would be "imposing a test of religious loyalty" that might jeopardize "the truce of tolerance by which Americans maintain civility and enlarge religious liberty".Starting in 1993, members of Historic Adventist splinter groups paid to have anti-Catholic billboards that called the Pope the Antichrist placed in various cities on the West Coast, including along Interstate 5

Interstate 5

Interstate 5 is the main Interstate Highway on the West Coast of the United States, running largely parallel to the Pacific Ocean coastline from Canada to Mexico . It serves some of the largest cities on the U.S...

from Portland to Medford, Oregon, and in Albuquerque, New Mexico. One such group took out an anti-Catholic ad on Easter Sunday in The Oregonian

The Oregonian

The Oregonian is the major daily newspaper in Portland, Oregon, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the U.S. west coast, founded as a weekly by Thomas J. Dryer on December 4, 1850...

, in 2000, as well as in newspapers in Coos Bay, Oregon and in Longview and Vancouver, Washington. Mainstream Seventh-day Adventists

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

denounced the advertisements. The contract for the last of the billboards in Oregon ran out in 2002.

Philip Jenkins

Philip Jenkins

Philip Jenkins is as of 2010 the Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Humanities at Pennsylvania State University . He was Professor and a Distinguished Professor of History and Religious studies at the same institution; and also assistant, associate and then full professor of Criminal Justice and...

, an Episcopalian historian, maintains that some who otherwise avoid offending members of racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups have no reservations about venting their hatred of Catholics.

In May 2006, a Gallup poll found 57% of Americans had a favorable view of the Catholic faith, while 30% of Americans had an unfavorable view. The Catholic Church's doctrines, and the priest sex abuse scandal were top issues for those who disapproved. "Greed", Roman Catholicism's view on homosexuality, and the celibate priesthood were low on the list of grievances for those who held an unfavorable view of Catholicism. While Protestants and Catholics themselves had a majority with a favorable view, those who are not Christian or are irreligious had a majority with an unfavorable view. In part, this represented a negative view toward all Christianity.

In April 2008, Gallup found that the number of Americans saying they had a positive view of U.S. Catholics had shrunk to 45% with 13% reporting a negative opinion. A substantial proportion of Americans, 41%, said their view of Catholics was neutral, while 2% of Americans indicated that they had a "very negative" view of Roman Catholics. However, with a net positive opinion of 32%, sentiment towards Catholics was more positive than that for both evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, who received net-positive opinions of 16 and 10% respectively. Gallup reported that Methodists and Baptists were viewed more positively than Catholics, as were Jews.

Human sexuality, contraception and abortion

Many people, including liberal feministsLiberal feminism

Liberal feminism asserts the equality of men and women through political and legal reform. It is an individualistic form of feminism and theory, which focuses on women’s ability to show and maintain their equality through their own actions and choices...

and LGBT

LGBT

LGBT is an initialism that collectively refers to "lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender" people. In use since the 1990s, the term "LGBT" is an adaptation of the initialism "LGB", which itself started replacing the phrase "gay community" beginning in the mid-to-late 1980s, which many within the...

activists, criticize the Catholic Church for its policies on issues relating to human sexuality, contraception and abortion.

On January 30, 2007, John Edwards' presidential campaign

John Edwards presidential campaign, 2008

John Edwards is the former United States Senator from North Carolina and was the Democratic nominee for Vice President in 2004. On December 28, 2006, he announced his entry into the 2008 Presidential election in the city of New Orleans near sites devastated by Hurricane Katrina...

hired Amanda Marcotte

Amanda Marcotte

Amanda Marie Marcotte is an American blogger best known for her writing on feminism and politics. Time magazine described her as "an outspoken voice of the left" and said "there is a welcome wonkishness to Marcotte, who, unlike some star bloggers, is not afraid to parse policy with her...

as blogmaster. The Catholic League

Catholic League (U.S.)

The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, often shortened to the Catholic League, is an American Catholic anti-defamation and civil rights organization...

, which is not an official organ of the Catholic Church, took offense at her obscenity- and profanity-laced invective against Catholic doctrine and "satiric" rants against Catholic leaders, including some of her earlier writings, where she described sexual activity of the Holy Spirit and claimed that the Church sought to "justify [its] misogyny with [...] ancient mythology." The Catholic League publicly demanded that the Edwards campaign terminate Marcotte's appointment. Marcotte subsequently resigned, citing "sexually violent, threatening e-mails" she had received as a result of the controversy.

Some LGBT

LGBT

LGBT is an initialism that collectively refers to "lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender" people. In use since the 1990s, the term "LGBT" is an adaptation of the initialism "LGB", which itself started replacing the phrase "gay community" beginning in the mid-to-late 1980s, which many within the...

activists have had a stormy relationship with the Catholic Church. In 1989 members of ACT UP and WHAM! disrupted a Sunday Mass at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York

The Cathedral of St. Patrick is a decorated Neo-Gothic-style Roman Catholic cathedral church in the United States...

to protest the Church’s position on homosexuality

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

, safer sex education

Safe sex

Safe sex is sexual activity engaged in by people who have taken precautions to protect themselves against sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS. It is also referred to as safer sex or protected sex, while unsafe or unprotected sex is sexual activity engaged in without precautions...

and the use of condoms. One hundred eleven protesters were arrested outside the Cathedral, and at least one protester inside threw used condoms at a Church altar and desecrated

Desecration

Desecration is the act of depriving something of its sacred character, or the disrespectful or contemptuous treatment of that which is held to be sacred or holy by a group or individual.-Detail:...

the Eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

during Mass. Protests against Proposition 8 supporters

Protests against Proposition 8 supporters

Protests against Proposition 8 supporters, including the Roman Catholic church and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints , which collaboratively campaigned in favor of California's Proposition 8 through volunteer and financial support for the measure, took place starting in November 2008...

at times threatened Catholic churches or organizations. Graffiti and swastikas were painted on Most Holy Redeemer Church, San Francisco

Most Holy Redeemer Church, San Francisco

Most Holy Redeemer Church in San Francisco, California, is a Roman Catholic parish situated in the Castro district, located at 100 Diamond Street...

, A printing plant of the Knights of Columbus

Knights of Columbus

The Knights of Columbus is the world's largest Catholic fraternal service organization. Founded in the United States in 1882, it is named in honor of Christopher Columbus....

, a Catholic organization that funded "Yes on 8", received threatening envelopes containing a white powder.

Anti-Catholicism in the entertainment industry

According to James Martin, S.J. the U.S. entertainment industry is of "two minds" about the Catholic Church. He argues that,On the one hand, film and television producers seem to find Catholicism irresistible. There are a number of reasons for this. First, more than any other Christian denomination, the Catholic Church is supremely visual, and therefore attractive to producers and directors concerned with the visual image. Vestments, monstrances, statues, crucifixes - to say nothing of the symbols of the sacraments - are all things that more "word oriented" Christian denominations have foregone. The Catholic Church, therefore, lends itself perfectly to the visual media of film and television. You can be sure that any movie about the Second Coming or Satan or demonic possession or, for that matter, any sort of irruption of the transcendent into everyday life, will choose the Catholic Church as its venue. (See, for example, End of DaysEnd of DaysEnd of Days is a 1999 American action horror thriller film directed by Peter Hyams starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Robin Tunney, Rod Steiger, Kevin Pollak, CCH Pounder, Udo Kier and Gabriel Byrne as Satan...

, DogmaDogma (film)Dogma is a 1999 American adventure fantasy comedy film written and directed by Kevin Smith, who also stars in the film along with an ensemble cast that includes Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Linda Fiorentino, Alan Rickman, Bud Cort, Salma Hayek, Chris Rock, Jason Lee, George Carlin, Janeane Garofalo,...

or StigmataStigmata (film)Stigmata is a 1999 supernatural horror film directed by Rupert Wainwright and starring Patricia Arquette as a hairdresser from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who is afflicted with the stigmata after acquiring a rosary formerly owned by a deceased Italian priest who himself suffered from the phenomena...

.)

Second, the Catholic Church is still seen as profoundly "other" in modern culture and is therefore an object of continuing fascination. As already noted, it is ancient in a culture that celebrates the new, professes truths in a postmodern culture that looks skeptically on any claim to truth, and speaks of mystery in a rational, post-Enlightenment world. It is therefore the perfect context for scriptwriters searching for the "conflict" required in any story.

He argues that, despite this fascination with the Catholic Church, the entertainment industry also holds contempt for the Church. "It is as if producers, directors, playwrights and filmmakers feel obliged to establish their intellectual bona fides by trumpeting their differences with the institution that holds them in such thrall."

Primary sources attacking Catholic Church

- Blanshard; Paul.American Freedom and Catholic Power Beacon Press, 1949, an influential attack on the Catholic Church

- Samuel W. Barnum. Romanism as It Is (1872), an anti-Catholic compendium online

- Rev. Isaac J. Lansing, M.A. Romanism and the Republic: A Discussion of the Purposes, Assumptions, Principles and Methods of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy (1890) Online