Atomic Spies

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, and Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

who are thought to have illicitly given information

Espionage

Espionage or spying involves an individual obtaining information that is considered secret or confidential without the permission of the holder of the information. Espionage is inherently clandestine, lest the legitimate holder of the information change plans or take other countermeasures once it...

about nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s production or design to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

and the early Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

. Exactly what was given, and whether everyone on the list gave it, is still a matter of some scholarly dispute, and in some cases what were originally seen as strong testimonies or confessions were admitted as fabricated in later years. Their work constitutes the most publicly well-known and well-documented case of nuclear espionage

Nuclear espionage

Nuclear espionage is the purposeful giving of state secrets regarding nuclear weapons to other states without authorization . During the history of nuclear weapons there have been many cases of known nuclear espionage, and also many cases of suspected or alleged espionage...

in the history of nuclear weapons

History of nuclear weapons

The history of nuclear weapons chronicles the development of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons possess enormous destructive potential derived from nuclear fission or nuclear fusion reactions...

. There was a movement among nuclear scientists to share the information with the world scientific community, but that was firmly quashed by the American government.

The modern day sharing of nuclear technology with Iran, Libya, North Korea and possibly other regimes on the part of Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan , also known in Pakistan as Mohsin-e-Pakistan , D.Eng, Sc.D, HI, NI , FPAS; more widely known as Dr. A. Q...

has yet to be fully explored. It is an open question whether the term "atom spy" will be applied to those operating outside the Cold War period, such as Khan and Argentine-American physicist Leonardo Mascheroni

Leonardo Mascheroni

Pedro Leonardo Mascheroni is a physicist who, according to the United States government, attempted to sell nuclear secrets to a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent posing as a Venezuelan spy. "U.S...

.

Whether the information significantly aided the speed of the Soviet atomic bomb project

Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet project to develop an atomic bomb , was a clandestine research and development program began during and post-World War II, in the wake of the Soviet Union's discovery of the United States' nuclear project...

is also disputed. While some of the information given could have aided in developing a nuclear weapon, the manner in which the heads of the Soviet bomb project actually used the information has led scholars to doubt its role in increasing the speed of development. According to this account, Igor Kurchatov

Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov , was a Soviet nuclear physicist who is widely known as the director of the Soviet atomic bomb project. Along with Georgy Flyorov and Andrei Sakharov, Kurchatov is widely remembered and dubbed as the "father of the Soviet atomic bomb" for his directorial role in the...

and Lavrenty Beria used the information primarily as a "check" against their own scientists' work and did not liberally share the information with them, distrusting both their own scientists as well as the espionage information. Later scholarship has also shown that the decisive brake on early Soviet development was not problems in weapons design but, as in the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, the difficulty in procuring fissile materials, especially since the Soviet Union had no uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

deposits known when it began its program (unlike the United States).

Confirmation about espionage work came from the VENONA project, which intercepted and decrypted Soviet intelligence reports sent during and after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. These provided clues to the identity of several spies at Los Alamos and elsewhere, some of whom have never been identified. Some of this information was available, but not usable in court for secrecy reasons, during the trials of the 1950s. As well records from Soviet archives, which were briefly opened to researchers after the fall of the Soviet Union, included more information about some spies.

Notable atomic spies

- Morris CohenMorris Cohen (Soviet spy)Morris Cohen also known in London as Peter Kroger was an American convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union. His wife Lona was also an agent.-Birth and education:...

– American, "Thanks to Cohen, designers of the Soviet atomic bomb got piles of technical documentation straight from the secret laboratory in Los Alamos," the newspaper Komsomolskaya PravdaKomsomolskaya PravdaKomsomolskaya Pravda is a daily Russian tabloid newspaper, founded on March 13th, 1925. It is published by "Izdatelsky Dom Komsomolskaya Pravda" .- History :...

said. Morris and his wife, Lona, served eight years in prison, less than half of their sentences before being released in a prisoner swap with The Soviet Union. He died without revealing the name of the American scientist who helped pass vital information about the United States atomic bomb project.

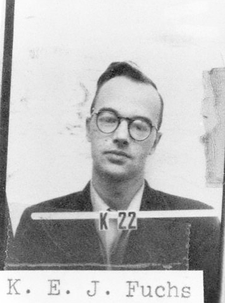

- Klaus FuchsKlaus FuchsKlaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

– German refugee and theoretical physicist who worked with the British delegation at Los AlamosLos Alamos National LaboratoryLos Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

during the Manhattan ProjectManhattan ProjectThe Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

. After Fuchs' confessionConfession (legal)In the law of criminal evidence, a confession is a statement by a suspect in crime which is adverse to that person. Some authorities, such as Black's Law Dictionary, define a confession in more narrow terms, e.g...

there was a trialTrial (law)In law, a trial is when parties to a dispute come together to present information in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court...

that lasted less than 90 minutes, Lord Goddard sentenceSentence (law)In law, a sentence forms the final explicit act of a judge-ruled process, and also the symbolic principal act connected to his function. The sentence can generally involve a decree of imprisonment, a fine and/or other punishments against a defendant convicted of a crime...

d him to fourteen years' imprisonmentImprisonmentImprisonment is a legal term.The book Termes de la Ley contains the following definition:This passage was approved by Atkin and Duke LJJ in Meering v Grahame White Aviation Co....

, the maximum for violating the Official Secrets ActOfficial Secrets ActThe Official Secrets Act is a stock short title used in the United Kingdom, Ireland, India and Malaysia and formerly in New Zealand for legislation that provides for the protection of state secrets and official information, mainly related to national security.-United Kingdom:*The Official Secrets...

. He escaped the charge of espionage because of the lack of independent evidence and because, at the time of the crime, the Soviet Union was not an enemy of Great Britain. In December 1950 he was stripped of his British citizenship. He was released on June 23, 1959, after serving nine years and four months of his sentence at Wakefield prisonWakefield (HM Prison)HM Prison Wakefield is a Category A men's prison, located in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. The prison is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service, and is the largest maximum security prison in the United Kingdom...

. He was allowed to emigrate to DresdenDresdenDresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

, then in the German Democratic RepublicGerman Democratic RepublicThe German Democratic Republic , informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city...

.

- Harry GoldHarry GoldHarry Gold was a laboratory chemist who was convicted of being the “courier” for a number of Soviet spy rings during the Manhattan Project.-Early life:Gold was born in Switzerland to poor Russian Jewish immigrants...

– American, confessed to acting as a courier for Greenglass and Fuchs. He was sentenced in 1951 to thirty years imprisonment. He was paroled in May 1966, after serving just over half of his sentence.

- David GreenglassDavid GreenglassDavid Greenglass was an atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked in the Manhattan project. He was the brother of Ethel Rosenberg.-Biography:...

– an American machinist at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. Greenglass confessed that he gave crude schematics of lab experiments to the Russians during World War II. Some aspects of his testimony against his sister and brother-in-law (the Rosenbergs, see below) are now thought to have been fabricated in an effort to keep his own wife, Ruth, from prosecution. Greenglass was sentenced to 15 years in prison, served 10 years, and later reunited with his wife.

- Theodore HallTheodore HallTheodore Alvin Hall was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on US efforts to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II , gave a detailed description of the "Fat Man" plutonium bomb, and of processes for purifying plutonium, to Soviet...

– a young American physicist at Los Alamos, whose identity as a spy was not revealed until very late in the twentieth century. He was never tried for his espionage work, though he seems to have admitted to it in later years to reporters and to his family.

- George Koval – The American born son of a BelorussianBelarusBelarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

emigrant family that returned to the Soviet Union where he was inducted into the Red Army and recruited into the GRUGRUGRU or Glavnoye Razvedyvatel'noye Upravleniye is the foreign military intelligence directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation...

intelligence service. He infiltrated the US Army and became a radiation health officer in the Special Engineering DetachmentSpecial Engineering DetachmentSpecial Engineer Detachment was a US Army program that identified enlisted personnel with technical skills, such as machining, or who had some science education beyond high school. Those identified were organized into the Special Engineer Detachment, or SED. SED personnel began arriving at Los...

. Acting under the code name DELMAR he obtained information from Oak RidgeOak Ridge National LaboratoryOak Ridge National Laboratory is a multiprogram science and technology national laboratory managed for the United States Department of Energy by UT-Battelle. ORNL is the DOE's largest science and energy laboratory. ORNL is located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, near Knoxville...

and the Dayton ProjectDayton ProjectThe Dayton Project was one of several sites involved in the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bombs. Charles Allen Thomas, an executive of the Monsanto Company corporation, was assigned to develop the neutron generating devices that triggered the nuclear detonation of the atomic bombs...

about the Urchin (detonator)Urchin (detonator)A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration is prompt critical. It is also known as an internal...

used on the Fat ManFat Man"Fat Man" is the codename for the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, by the United States on August 9, 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons to be used in warfare to date , and its detonation caused the third man-made nuclear explosion. The name also refers more...

plutonium bomb. His work was not known to the west until he was posthumously recognized as a hero of the Russian Federation by Vladimir PutinVladimir PutinVladimir Vladimirovich Putin served as the second President of the Russian Federation and is the current Prime Minister of Russia, as well as chairman of United Russia and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Russia and Belarus. He became acting President on 31 December 1999, when...

in 2007.

- Irving LernerIrving LernerIrving Lerner Before becoming a filmmaker, Lerner was a research editor for Columbia University's Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, getting his start in film by making documentaries for the anthropology department. In the early 1930s, he was a member of the Workers Film and Photo League, and later,...

An American film director, he was caught photographing the cyclotronCyclotronIn technology, a cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator. In physics, the cyclotron frequency or gyrofrequency is the frequency of a charged particle moving perpendicularly to the direction of a uniform magnetic field, i.e. a magnetic field of constant magnitude and direction...

at the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, BerkeleyThe University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

in 1944. After the war he was blacklisted.

- Allan Nunn May – A British citizen, he was one of the first Soviet spies uncovered during the cold war. He worked on the Manhattan Project and was betrayed by a Soviet defector in CanadaIgor GouzenkoIgor Sergeyevich Gouzenko was a cipher clerk for the Soviet Embassy to Canada in Ottawa, Ontario. He defected on September 5, 1945, with 109 documents on Soviet espionage activities in the West...

. His was uncovered in 1946 and it led the United States to restrict the sharing of atomic secrets with Britain. On May 1, 1946, he was sentenced to ten years hard labour. He was released in 1952, after serving six and a half years.

- Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – Americans who were involved in coordinating and recruiting an espionage network that included Ethel's brother, David Greenglass. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were tried for conspiracy to commit espionage, since the prosecution seemed to feel that there was not enough evidence to convict on espionage. Treason charges were not applicable, since the United States and the Soviet Union were allies at the time. The Rosenbergs denied all the charges but were convicted in a trial in which the prosecutor Roy CohnRoy CohnRoy Marcus Cohn was an American attorney who became famous during Senator Joseph McCarthy's investigations into Communist activity in the United States during the Second Red Scare. Cohn gained special prominence during the Army–McCarthy hearings. He was also an important member of the U.S...

said he was in daily secret contact with the judge, Irving KaufmanIrving KaufmanIrving Robert Kaufman was a federal judge in the United States. He is best remembered for imposing the controversial death sentences on Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.-Biography:...

. Despite an international movement demanding clemency, and appeals to President Dwight D. EisenhowerDwight D. EisenhowerDwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

by leading European intellectuals and the Pope, the Rosenbergs were executed at the height of the Korean WarKorean WarThe Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

. President Eisenhower wrote to his son, serving in Korea, that if he spared Ethel (presumably for the sake of her children), then the Soviets would simply recruit their spies from among women.

- Saville SaxSaville SaxSaville Sax was the Harvard University roommate of Theodore Hall who recruited Hall for the Soviets and acted as a courier to move the atomic secrets from Los Alamos to the Soviets.-Biography:...

– American acted as the courier for Klaus FuchsKlaus FuchsKlaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who in 1950 was convicted of supplying information from the American, British and Canadian atomic bomb research to the USSR during and shortly after World War II...

and Theodore HallTheodore HallTheodore Alvin Hall was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on US efforts to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II , gave a detailed description of the "Fat Man" plutonium bomb, and of processes for purifying plutonium, to Soviet...

.

- Morton SobellMorton SobellMorton Sobell is a former spy for the Soviet Union. Sobell was an American engineer working for General Electric and Reeves Electronics on military and government contracts. He was found guilty of spying for the Soviets , and sentenced to 30 years in prison...

– American engineer tried and convicted along with the Rosenbergs, was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment but released from Alcatraz in 1969, after serving 17 years and 9 months. After proclaiming his innocence for over half a century, Sobell admitted spying for the Soviets, and implicated Julius Rosenberg, in an interview with the New York Times published on September 11, 2008.

Further reading

- Alexei Kojevnikov, Stalin's Great Science: The Times and Adventures of Soviet Physicists (Imperial College Press, 2004). ISBN 1-86094-420-5 (use of espionage data by Soviets)

- Gregg Herken, Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2002). ISBN 0-8050-6588-1 (details on Fuchs)

- Richard RhodesRichard RhodesRichard Lee Rhodes is an American journalist, historian, and author of both fiction and non-fiction , including the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Making of the Atomic Bomb , and most recently, The Twilight of the Bombs...

, Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995). ISBN 0-684-80400-X (general overview of Fuchs and Rosenberg cases)