Australian folklore

Encyclopedia

Australian Aboriginal mythology

- BunyipBunyipThe bunyip, or kianpraty, is a large mythical creature from Aboriginal mythology, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes....

- According to legend, they are said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes. - Rainbow serpentRainbow SerpentThe Rainbow Serpent is a common motif in the art and mythology of Aboriginal Australia. It is named for the snake-like meandering of water across a landscape and the colour spectrum caused when sunlight strikes water at an appropriate angle relative to the observer.The Rainbow Serpent is seen as...

- It is the sometimes unpredictable Rainbow Serpent, who vies with the ever-reliable Sun, that replenishes the stores of water, forming gullies and deep channels as he slithered across the landscape, allowing for the collection and distribution of water. - YowieYowie (cryptid)Yowie is the term for an unidentified hominid reputed to lurk in the Australian wilderness. It is an Australian cryptid similar to the Himalayan Yeti and the North American Bigfoot....

- In Aboriginal mythology this is said to be a giant beast, resembling a cross between a lizard and an ant. It emerges from the ground at night to eat whatever it can find - even humans. But by daylight it settles. See below for the Yowie of modern context.

Animals/creatures

- Drop bearDrop bearA drop bear is a fictitious Australian marsupial. Drop bears are commonly said to be unusually large, vicious, carnivorous koalas that inhabit treetops and attack their prey by dropping onto their heads from above...

- Stories of drop bears are frequently related to visiting tourists as a joke. (see also the Queensland TigerQueensland TigerThe Queensland tiger is a cryptid reported to live in the Queensland area in eastern Australia.Also known by its native name, the yarri, it is described as being a dog-sized feline with stripes and a long tail, prominent front teeth and a savage temperament...

) - Gippsland phantom catGippsland phantom catThe Gippsland Big Cat is a cryptid.Although feral cats are present in Victoria as in the rest of Australia and there have been hundreds of reported sightings, yet no proof of the existence of big cats has even been established.-Sightings:...

- an urban legend centered on the idea that United States soldiers based in Victoria, in the swamps of the Greta area, in Victoria, Australia. - LyrebirdLyrebirdA Lyrebird is either of two species of ground-dwelling Australian birds, that form the genus, Menura, and the family Menuridae. They are most notable for their superb ability to mimic natural and artificial sounds from their environment. Lyrebirds have unique plumes of neutral coloured...

- The Lyrebird is said to mimic a wide variety of sounds. They have been said to be able to mimic chainsaws and cars http://www.museum.vic.gov.au/forest/animals/lyrebird.html, alarms, horns, and even trains. http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/npws.nsf/Content/Lyrebirds. There is a story about a lyrebird that used to halt 19th Century logging operations by mimicking the fire siren. - MegalaniaMegalaniaMegalania is a giant extinct goanna or monitor lizard. It was part of a megafaunal assemblage that inhabited southern Australia during the Pleistocene, and appears to have disappeared around 40,000 years ago...

- a giant goannaGoannaGoanna is the name used to refer to any number of Australian monitor lizards of the genus Varanus, as well as to certain species from Southeast Asia.There are around 30 species of goanna, 25 of which are found in Australia...

(lizard), generally believed to be extinct. However, there have been numerous reports and rumors of living Megalania in Australia, and occasionally New Guinea, but the only physical evidence that Megalania might still be alive today are plaster casts of possible Megalania footprints made in 1979. - Tasmanian tigerThylacineThe thylacine or ,also ;binomial name: Thylacinus cynocephalus, Greek for "dog-headed pouched one") was the largest known carnivorous marsupial of modern times. It is commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or the Tasmanian wolf...

- despite the widely held view that the Thylacine (or Tasmanian tiger) became extinct during the 1930s, accounts of sightings in eastern Victoria and parts of Tasmania have persisted to the present day. - Yowie (cryptid)Yowie (cryptid)Yowie is the term for an unidentified hominid reputed to lurk in the Australian wilderness. It is an Australian cryptid similar to the Himalayan Yeti and the North American Bigfoot....

- In the modern context, the Yowie is the generic (and somewhat affectionate) term for an unidentified hominid reputed to lurk in the Australian wilderness, analogous to the Himalayan YetiYetiThe Yeti or Abominable Snowman is an ape-like cryptid said to inhabit the Himalayan region of Nepal, and Tibet. The names Yeti and Meh-Teh are commonly used by the people indigenous to the region, and are part of their history and mythology...

and the North American BigfootBigfootBigfoot, also known as sasquatch, is an ape-like cryptid that purportedly inhabits forests, mainly in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Bigfoot is usually described as a large, hairy, bipedal humanoid...

. See above for the Yowie of Aboriginal mythology.

People

- Don BradmanDonald BradmanSir Donald George Bradman, AC , often referred to as "The Don", was an Australian cricketer, widely acknowledged as the greatest batsman of all time...

- perhaps the greatest cricketer ever, the fact that he needed only 4 runs in his last innings in order to retire with a test average of 100 but was uncharacteristically bowled for a duck (leaving him stranded on an average of 99.94) has become a part of Australian folklore and added greatly to his mystique. (there are rumours that he has made the 4 runs in another match that was miscounted) - William BuckleyWilliam Buckley (convict)William Buckley was an English convict who was transported to Australia, escaped, was given up for dead and lived in an Aboriginal community for many years....

- an Australian convict who escaped and became famous for living in an Aboriginal community for many years. - Azaria Chamberlain - the name of two-month-old Australian baby who disappeared on the night of 17 August 1980 on a camping trip with her family. Her parents, Lindy Chamberlain and Michael Chamberlain, reported that she had been taken from their tent by a dingoDingoThe Australian Dingo or Warrigal is a free-roaming wild dog unique to the continent of Australia, mainly found in the outback. Its original ancestors are thought to have arrived with humans from southeast Asia thousands of years ago, when dogs were still relatively undomesticated and closer to...

, but they were arrested, tried, and convicted of her murder in 1982. Both were later cleared, and thus the case is best remembered for what was an injustice. The Chamberlains were Seventh-day AdventistsSeventh-day Adventist ChurchThe Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

and an urban myth had developed that they were required to sacrifice a child as part of their religious beliefs and that the name Azaria meant "sacrifice". These statements are false. - Dawn FraserDawn FraserDawn Fraser AO, MBE is an Australian champion swimmer. She is one of only two swimmers to win the same Olympic event three times – in her case the 100 meters freestyle....

- perhaps the greatest Australian female swimmer of all time. Known for her politically incorrectPolitical correctnessPolitical correctness is a term which denotes language, ideas, policies, and behavior seen as seeking to minimize social and institutional offense in occupational, gender, racial, cultural, sexual orientation, certain other religions, beliefs or ideologies, disability, and age-related contexts,...

behaviour or larrikinLarrikinismLarrikinism is the name given to the Australian folk tradition of irreverence, mockery of authority and disregard for rigid norms of propriety. Larrikinism can also be associated with self-deprecating humour.- Etymology :...

character as much as her athletic ability, Fraser won eight OlympicOlympic GamesThe Olympic Games is a major international event featuring summer and winter sports, in which thousands of athletes participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition where more than 200 nations participate...

medals, including four golds, and six Commonwealth GamesCommonwealth GamesThe Commonwealth Games is an international, multi-sport event involving athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations. The event was first held in 1930 and takes place every four years....

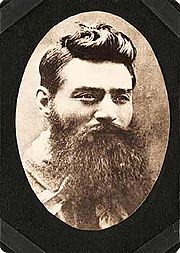

gold medals. It was alleged that she took the flag from Emperor Hirohito's palace, while this was proved false, the incident became part of the folklore. - Ned KellyNed KellyEdward "Ned" Kelly was an Irish Australian bushranger. He is considered by some to be merely a cold-blooded cop killer — others, however, consider him to be a folk hero and symbol of Irish Australian resistance against the Anglo-Australian ruling class.Kelly was born in Victoria to an Irish...

- Australian 19th century bushranger, many films, books and artworks have been made about him, possibly his exploits have been exaggerated in the public eye and become something of folklore. It especially surrounds his capture at Glenrowan where the Kelly gang tried to derail a train of Victorian police which were arriving, and where surrounded in the hotel, they had made armour from stolen iron mould boards of ploughs, and came out shooting, whereupon they shot in the feet. The image of Ned Kelly with a helmet with just a small slit for the eyes is very much a part of this. - Dame Nellie MelbaNellie MelbaDame Nellie Melba GBE , born Helen "Nellie" Porter Mitchell, was an Australian operatic soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian Era and the early 20th century...

- an Australian operaOperaOpera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes and sometimes includes dance...

sopranoSopranoA soprano is a voice type with a vocal range from approximately middle C to "high A" in choral music, or to "soprano C" or higher in operatic music. In four-part chorale style harmony, the soprano takes the highest part, which usually encompasses the melody...

, the first Australian to achieve international recognition in the form. The French dessert Peach MelbaPeach MelbaThe Peach Melba is a classic dessert, invented in 1892 or 1893 by the French chef Auguste Escoffier at the Savoy Hotel, London to honour the Australian soprano, Nellie Melba. It combines two favourite summer fruits: peaches and raspberry sauce accompanying vanilla ice cream.In 1892, Nellie Melba...

is named after her. Many old theatre halls in regional Australia persist with rumours that she once graced their stage, most notably, that of the gold mining town of GulgongGulgong, New South WalesGulgong is a 19th century gold rush town in the Central-West of the Australian state of New South Wales. The town is located about north west of Sydney, and about 30 km north of Mudgee along the Castlereagh Highway. At the 2006 census, Gulgong had a population of 1,907 people...

in NSW. She is also remembered in the vernacular Australian expression "more comebacks than Nellie Melba", which satirised her seemingly endless series of 'retirement' tours in the 1920s. - PemulwuyPemulwuyPemulwuy was an Aboriginal Australian man born around 1750 in the area of Botany Bay in New South Wales. He is noted for his resistance to the European settlement of Australia which began with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. He is believed to have been a member of the Bidjigal clan of...

- an AboriginalIndigenous AustraliansIndigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

rebel against the BritishBritish EmpireThe British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

during the 18th century and early 19th Century, believed to have impossibly escaped from capture on countless occasions. - Harold HoltHarold HoltHarold Edward Holt, CH was an Australian politician and the 17th Prime Minister of Australia.His term as Prime Minister was brought to an early and dramatic end in December 1967 when he disappeared while swimming at Cheviot Beach near Portsea, Victoria, and was presumed drowned.Holt spent 32 years...

- a Prime MinisterPrime Minister of AustraliaThe Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

who disappeared while swimming in 1967. Popular theories include Holt being picked up by a Chinese submarine, faking his own death, suicide, and CIA involvement. An eventual inquest in 2005 determined that he drowned accidentally. - Squizzy TaylorSquizzy TaylorJoseph Leslie Theodore "Squizzy" Taylor was an Australian Melbourne-based gangster. He rose to notoriety by leading a violent gang war against a rival criminal faction in 1919, absconding from bail and successfully hiding from the police for over a year in 1921-22, and the Glenferrie robbery in...

- a petty criminal turned gangster from MelbourneMelbourneMelbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

. He is believed to have constructed a series of underground tunnels throughout the inner suburbs of FitzroyFitzroy, VictoriaFitzroy is an inner city suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Yarra. Its borders are Alexandra Parade , Victoria Parade , Smith Street and Nicholson Street. Fitzroy is Melbourne's...

and CollingwoodCollingwood, VictoriaCollingwood is an inner city suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 3 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Yarra...

. - Mary MackillopMary MacKillopMary Helen MacKillop , also known as Saint Mary of the Cross, was an Australian Roman Catholic nun who, together with Father Julian Tenison Woods, founded the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart and a number of schools and welfare institutions throughout Australasia with an emphasis on...

- Australia's first saint, responsible for miracles such as curing a woman of leukemia after her family prayed for it. - Erroll Flynn - the first Australian-born actor to make it in Hollywood

Places

- Finke RiverFinke RiverThe Finke River is one of the largest rivers in central Australia. Its source is in the Northern Territory's MacDonnell Ranges, and the name Finke River is first applied at the confluence of the Davenport and Ormiston Creeks, just north of Glen Helen. From here the river meanders for approximately...

- "oldest river in the world", a claim that has been attributed to "scientists" by a generation of central Australian bus drivers and tour brochure writers. Parts of the Finke River are old, but the "oldest river" claim doesn't come from the scientific literature. - GallipoliGallipoliThe Gallipoli peninsula is located in Turkish Thrace , the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles straits to the east. Gallipoli derives its name from the Greek "Καλλίπολις" , meaning "Beautiful City"...

- the name of a peninsula in TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, but also the name given to the Allied CampaignBattle of GallipoliThe Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

on that peninsula during World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. There were around 180,000 Allied casualties and 220,000 Turkish casualties. This campaign has become a "founding mythFounding mythA national myth is an inspiring narrative or anecdote about a nation's past. Such myths often serve as an important national symbol and affirm a set of national values. A national myth may sometimes take the form of a national epic...

" for both AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

and New ZealandNew ZealandNew Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, and Anzac DayANZAC DayAnzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand, commemorated by both countries on 25 April every year to honour the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who fought at Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It now more broadly commemorates all...

is still commemorated as a holiday in both countries. The idea that Australian soldiers were mowed down by Turkish gunfire following stupid decisions of the British commanding officers is part of the folklore, as is the escape from Gallipoli, where the AnzacAustralian and New Zealand Army CorpsThe Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was formed in Egypt in 1915 and operated during the Battle of Gallipoli. General William Birdwood commanded the corps, which comprised troops from the First Australian Imperial...

s used rifles rigged to fire by water dripped into a pan attached to the trigger to make it seem like there were still soldiers in the trenches as they were leaving. Another aspect of the ANZAC spiritANZAC spiritThe Anzac spirit or Anzac legend is a concept which suggests that Australian and New Zealand soldiers possess shared characteristics, specifically the qualities those soldiers are believed to have shown on the battlefield in World War I. These qualities cluster around several ideas, including...

is the story of Simpson and his donkey. - Sydney-Melbourne rivalryAustralian regional rivalriesAustralian regional rivalries refers to the rivalries between Australian cities or regions.-Sydney - Melbourne rivalry:There has been a long standing rivalry between the cities of Sydney and Melbourne, the two largest cities in Australia...

- there has been a long standing rivalry, usually friendly yet sometimes heated, between the cities of Melbourne and Sydney, the two largest cities in Australia. It was this very rivalry that ultimately acted as the catalyst for the eventual founding of CanberraCanberraCanberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

as the capital city of Australia. - Snowy RiverSnowy RiverThe Snowy River is a major river in south-eastern Australia. It originates on the slopes of Mount Kosciuszko, Australia's highest mainland peak, draining the eastern slopes of the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales, before flowing through the Snowy River National Park in Victoria and emptying into...

- immortalised in another Banjo Paterson poem, The Man from Snowy River. The river has received much attention of late for now being nothing more than a trickle, and in fact has become a symbol for wider Australian interest in the health of its great rivers, particularly those in the Murray-Darling basinMurray-Darling BasinThe Murray-Darling basin is a large geographical area in the interior of southeastern Australia, whose name is derived from its two major rivers, the Murray River and the Darling River. It drains one-seventh of the Australian land mass, and is currently by far the most significant agricultural...

. - Sydney Harbour BridgeSydney Harbour BridgeThe Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge across Sydney Harbour that carries rail, vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic between the Sydney central business district and the North Shore. The dramatic view of the bridge, the harbour, and the nearby Sydney Opera House is an iconic...

-- Australia's most famous national landmark. - The Great Barrier Reef -- the only landmark in Australia (or Oceania) to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Socio-political events

- Australian constitutional crisis of 1975Australian constitutional crisis of 1975The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis has been described as the greatest political crisis and constitutional crisis in Australia's history. It culminated on 11 November 1975 with the removal of the Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party , by Governor-General Sir John Kerr...

- a real political crisis that has since taken on mythic proportions and elevated the protagonists to legendary status (depending on which side of the debate one takes). A visiting American politician at the time wryly observed that he was sure he had only heard the tip of the ice cube. Gough WhitlamGough WhitlamEdward Gough Whitlam, AC, QC , known as Gough Whitlam , served as the 21st Prime Minister of Australia. Whitlam led the Australian Labor Party to power at the 1972 election and retained government at the 1974 election, before being dismissed by Governor-General Sir John Kerr at the climax of the...

's speech "Well may we say God save the QueenGod Save the Queen"God Save the Queen" is an anthem used in a number of Commonwealth realms and British Crown Dependencies. The words of the song, like its title, are adapted to the gender of the current monarch, with "King" replacing "Queen", "he" replacing "she", and so forth, when a king reigns...

, but nothing will save the Governor General" is replayed frequently.

- Eureka stockadeEureka StockadeThe Eureka Rebellion of 1854 was an organised rebellion by gold miners which occurred at Eureka Lead in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. The Battle of Eureka Stockade was fought on 3 December 1854 and named for the stockade structure erected by miners during the conflict...

- a miners' revolt in 1854 in VictoriaVictoria (Australia)Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

, AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

against the officials supervising the goldGoldGold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

-miningMiningMining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

region of BallaratBallarat, VictoriaBallarat is a city in the state of Victoria, Australia, approximately west-north-west of the state capital Melbourne situated on the lower plains of the Great Dividing Range and the Yarrowee River catchment. It is the largest inland centre and third most populous city in the state and the fifth...

, in particular, the high prices of digging licenses. It is often regarded as the "Birth of Australian Democracy" and an event of equal significance to Australian historyHistory of AustraliaThe History of Australia refers to the history of the area and people of Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding Indigenous and colonial societies. Aboriginal Australians are believed to have first arrived on the Australian mainland by boat from the Indonesian archipelago between 40,000 to...

as the storming of the BastilleStorming of the BastilleThe storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris on the morning of 14 July 1789. The medieval fortress and prison in Paris known as the Bastille represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. While the prison only contained seven inmates at the time of its storming, its fall was the flashpoint...

was to French historyHistory of FranceThe history of France goes back to the arrival of the earliest human being in what is now France. Members of the genus Homo entered the area hundreds of thousands years ago, while the first modern Homo sapiens, the Cro-Magnons, arrived around 40,000 years ago...

, but almost equally often dismissed as an event of little long-term consequence. However, the Eureka flag has achieved iconic status over the decades, the mining term "digger" entered the Australian lexicon carrying a variety of positive images (also used to describe the ANZ soldiers of World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, but also used as a term of affection more generally) and the event itself remains an early expression of the Australian identity: disdain for the ruling elite, egalitarianism, and a fair go.

Sport

- Australia IIAustralia IIAustralia II is the Australian 12-metre-class challenge racing yacht that was launched in 1982 and won the 1983 America's Cup for the Royal Perth Yacht Club...

- a 12-metre class12-metre classThe 12 Metre Class is a rating class for racing boats designed to the International rule. It enables fair competition between boats that rate in the class whilst retaining the freedom to experiment with the details of their designs. The first 12 Metres were built in 1907. The 12 Metre Class was...

yachtYachtA yacht is a recreational boat or ship. The term originated from the Dutch Jacht meaning "hunt". It was originally defined as a light fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries...

that was the first successful challenger for the America's CupAmerica's CupThe America’s Cup is a trophy awarded to the winner of the America's Cup match races between two yachts. One yacht, known as the defender, represents the yacht club that currently holds the America's Cup and the second yacht, known as the challenger, represents the yacht club that is challenging...

after 132 years. On the morning of the victory (Australian time) the then Australian Prime Minister, Bob HawkeBob HawkeRobert James Lee "Bob" Hawke AC GCL was the 23rd Prime Minister of Australia from March 1983 to December 1991 and therefore longest serving Australian Labor Party Prime Minister....

, famously said that any employer who sacked any of their employees for not coming in that day was a "bum". The challenge also resulted in the popularisation of the Boxing KangarooBoxing KangarooThe boxing kangaroo is a national symbol of Australia, frequently seen in popular culture. The symbol is often displayed prominently by Australian spectators at sporting events, such as at cricket, tennis and football matches, and at the Commonwealth and Olympic Games. The flag is also highly...

representation. - ColliwobblesCollingwood Football ClubThe Collingwood Football Club, nicknamed The Magpies, is an Australian rules football club which plays in the Australian Football League...

- The "colliwobbles" refers to the Collingwood Football Club's apparent penchant for losing grand finals over a 32 year period between 1958 and 1990. During this premiership drought, fans endured nine fruitless grand finals (1960, 1964, 1966, 1970, 1977 (drawn, then lost in a replay the following week), 1979, 1980, 1981). The term "Colliwobbles" was to enter the Victorian vocabulary to signify a choking phenomenon.

- Phar LapPhar LapPhar Lap was a champion Thoroughbred racehorse whose achievements captured the public's imagination during the early years of the Great Depression. Foaled in New Zealand, he was trained and raced in Australia. Phar Lap dominated Australian racing during a distinguished career, winning a Melbourne...

- a thoroughbredThoroughbredThe Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word thoroughbred is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed...

horseHorseThe horse is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus, or the wild horse. It is a single-hooved mammal belonging to the taxonomic family Equidae. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature into the large, single-toed animal of today...

who is considered by many to be the world's greatest racehorse, and is probably subject to more conspiracy theories than any other racehorse (in relation to the cause of his death). His name entered the Australian lexicon in the expression to have a heart bigger than Phar Lap's, referring to someone's tenacity and courage. It is part of Australian folklore that Phar Laps' heart was physically twice the size of the average horse's heart. - Wally LewisWally LewisWalter James "Wally" Lewis AM is an Australian former professional rugby league footballer and coach. Currently a commentator of the sport, he is widely regarded as the greatest rugby league player of all time...

-- legendary rugby player, captained the Queensland rugby team in The State of OriginState of OriginState of Origin is the name used in Australia for one existing sporting event which involves domestic representative teams. The term, when used in isolation, usually refers to rugby league football, and occassionally Australian Football matches, in which players are selected for the Australian...

a record 30 times.

Other

- 5 o'clock wave - supposedly a large wave, several metres in height and created by the daily release of dam overflow, that is said to travel downriver at high speed, and to reach the location at which the tale is being told at 5 o'clock each afternoon.

- Big ThingsAustralia's Big ThingsThe Big Things of Australia are a loosely related set of large structures or sculptures. There are estimated to be over 150 such objects around the country, the first being the Big Scotsman in Medindie, Adelaide, which was built in 1963....

- many Australian towns are known for their large structures or sculptures. - Clancy of the OverflowClancy of the Overflow"Clancy of The Overflow" is a poem by Banjo Paterson, first published in The Bulletin, an Australian news magazine, on 21 December 1889. The poem is typical of Paterson, offering a romantic view of rural life, and is one of his best-known works.-History:...

- a poem by Banjo Paterson - Geelong KeysGeelong KeysThe Geelong Keys were a set of keys discovered in 1845 or 1846 in the time of Governor Charles La Trobe at Corio Bay in Victoria, Australia. They were embedded in the stone of the beach in such a way as to make him believe that they had been there for 100–150 years...

- set of keys discovered in 1845 or 1846 by Governor Charles La TrobeCharles La TrobeCharles Joseph La Trobe was the first lieutenant-governor of the colony of Victoria .-Early life:La Trobe was born in London, the son of Christian Ignatius Latrobe, a family of Huguenot origin...

at Corio Bay in Victoria, Australia - Lasseter's ReefLasseter's ReefLasseter's Reef refers to the purported discovery, in 1897, of a fabulously rich gold deposit in a remote and desolate corner of central Australia...

- a fabulously rich gold deposit said to have been discovered - and then subsequently lost - by bushman Harold Bell LasseterLewis Hubert (Harold Bell) LasseterLewis Hubert Lasseter, or Lewis Harold Bell Lasseter as he later referred to himself, was born on 27 September 1880 at Bamganie, Victoria, Australia. Though self-educated, he was literate and well-spoken, but commonly described as eccentric and opinionated...

in a remote and desolate corner of central Australia towards the end of the 19th Century. - Mahogany ShipMahogany ShipThe Mahogany Ship refers to a putative, early shipwreck that is purported to lie beneath the sand in the Armstrong Bay area, approximately 3 to 6 kilometres west of Warrnambool in southwest Victoria, Australia...

- a supposed wrecked Portuguese caravel which is purported to lie beneath the sand approximately six miles west of Warrnambool in southwest Victoria, Australia. - Marree ManMarree ManThe Marree Man, or Stuart's Giant, is a modern geoglyph discovered by air on 26 June 1998. It appears to depict an indigenous Australian man, most likely of the Pitjantjatjara tribe, hunting birds or wallabies with a throwing stick. It lies on a plateau at Finnis Springs 60 km west of the...

- A large geoglyphGeoglyphA geoglyph is a large design or motif produced on the ground and typically formed by clastic rocks or similarly durable elements of the geography, such as stones, stone fragments, gravel, or earth...

located near Marree in South Australia. Mystery surrounds how it was created, and who created it. - Min Min lightMin Min lightMin Min Light is the name given to an unusual light formation that has been reported numerous times in eastern Australia. The lights have been reported from as far south as Brewarrina in western New South Wales, to as far north as Boulia in northern Queensland...

- an unexplained light seen in central Australia. - Nullarbor NymphNullarbor NymphThe Nullarbor Nymph, referring to supposed sightings of a half naked woman living amongst kangaroos on the Nullarbor Plain, was a hoax perpetrated in Australia between 1971 and 1972....

- a hoax and legend in 1971 and 1972 in Australia which grew from the supposed sighting of a half naked woman on the Nullarbor Plain living amongst some kangaroos. - SpeewahSpeewahThe Speewah is a mythical Australian station that is the subject of many 'tall tales' told by Australian bushmen. The stories of the Speewah are Australian folktales of unwritten literature of men who never had the opportunity to read books and who became tellers of tales instead...

- a mythical Australian station that is the subject of many 'tall tales' told by Australian bushmen. - Waltzing MatildaWaltzing Matilda"Waltzing Matilda" is Australia's most widely known bush ballad. A country folk song, the song has been referred to as "the unofficial national anthem of Australia"....

- Extensive folklore surrounds the song and the process of its creation, to the extent that the song has its own museum.