Barthélemy Boganda

Encyclopedia

Barthélemy Boganda was the leading nationalist

politician of what is now the Central African Republic

. Boganda was active prior to his country's independence, during the period when the area, part of French Equatorial Africa

, was administered by France

under the name of Oubangui-Chari

. He served as the first Prime Minister of the Central African Republic autonomous territory.

Boganda was born into a family of subsistence farmers, and was adopted and educated by Roman Catholic Church

missionaries

. In 1938, he was ordained as the first Roman Catholic priest from Oubangui-Chari. During World War II

, Boganda served in a number of missions and after was persuaded by the Bishop of Bangui

to enter politics. In 1946, he became the first Oubanguian elected to the French National Assembly, where he maintained a political platform

against racism

and the colonial regime

. He then returned to Oubangui-Chari to form a grassroots movement in opposition of French colonialism

. The movement led to the foundation of the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa

(MESAN), and became popular among villagers and the working class

. Boganda's reputation was slightly damaged when he was laicized

from the priesthood after marrying Michelle Jourdain, a parliamentary secretary. Nonetheless, he continued to advocate for equal treatment and civil rights

for blacks in the territory well into the 1950s.

In 1958, after the French Fourth Republic

began to consider granting independence to most of its African colonies, Boganda met with Prime Minister

Charles de Gaulle

to discuss terms for the independence of Oubangui-Chari. De Gaulle accepted Boganda's terms, and on 1 December, Boganda declared the establishment of the Central African Republic. He became the autonomous territory's first Prime Minister and intended to serve as the first President of the independent CAR. He was killed in a mysterious plane crash on 29 March 1959, while en route to Bangui. Experts found a trace of explosives in the plane's wreckage, but revelation of this detail was withheld. Although those responsible for the crash were never identified, people have suspected the French secret service, and even Boganda's wife, of being involved. Slightly more than one year later, Boganda's dream was realized, when the Central African Republic attained formal independence from France.

in Bobangui

, a large M'Baka

village in the Lobaye

basin located at the edge of the equatorial forest some 80 kilometres (49.7 mi) southwest of Bangui

. French commercial exploitation of Central Africa had reached an apogee around the time of Boganda's birth, and although interrupted by World War I

, activity resumed in the 1920s. The French consortia used what was essentially a form of slavery—the corvée—and one of the most notorious was the Compagnie forestière de la Sangha-Oubangui, involved in rubber gathering in the Lobaye district.

In the late 1920s, Boganda's mother was beaten to death by the company's officials while collecting rubber in the forest. His uncle, whose son Jean-Bédel Bokassa

would later crown himself as the Emperor of the Central African Empire

, was beaten to death at the colonial police station as a result of his alleged resistance to work

. Boganda's father was a witch doctor

who had engaged in cannibalistic

rituals.

During his early years, Boganda was adopted by Catholic missionaries. As a boy he attended the school opened at Mbaiki

(the administrative centre for the Lobaye prefecture

) by the post's founder, Lieutenant Mayer. From December 1921 to December 1922, he spent two hours a day with Monsignor

Jean-Réné Calloch learning how to read, while spending the rest of his time performing manual labour. On December 24, he was received into the church under the name Barthélemy, in honour of one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ who was believed to have worked as Christian missionary

in Africa. Father Gabriel Herrau sent Boganda to the Catholic School of Betou and then to the school of the Saint Paul Mission at Bangui, where he completed his primary studies under Mgr Calloch, whom he would consider his spiritual father. The missionaries there, encouraged by his intellectual promise and pious demeanour, helped him continue secondary studies at small seminaries in Brazzaville

and Kisantu

(under Belgian

Jesuits

) before he moved on to the great seminary at Yaoundé

. On 17 March 1938, fulfilling an ambition he had had since age twelve, he was ordained and became the first Roman Catholic

priest native to Oubangui-Chari

, as the colony was then called. He ministered at Bangui, Grimari

and Bangassou

, and in 1939, his bishop denied his request to join the French Army

. He was needed at home, as many Frenchmen involved with the church had been called back to the metropole to fight in World War II

, during which he served in a number of missions.

to the assembly after winning almost half of the total votes cast and defeating three other candidates, including the outgoing incumbent, François Joseph Reste, who had formerly served as the Governor-General of French Equatorial Africa

. Boganda arrived in Paris

attired in his clerical garb and introduced himself to his fellow legislators as the son of a polygamous cannibal. From 1947 on, Boganda conducted a lively campaign against racism and the colonial regime. Soon realizing the limits of his influence in France (he served in parliament until 1958 but gradually detached himself from its activities), he returned to Oubangui-Chari to organise a grassroots movement of teachers, truck drivers and small producers to oppose French colonialism, although his previous attempt to set up a marketing cooperative among African planters of his own ethnicity had failed. On 28 September 1949, at Bangui, he founded the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN), a quasi-religious political movement

and party

that sought to affirm black humanity and quickly came to dominate local politics. His political creed was summed up in the Sango

phrase "zo kwe zo", which translated to "every human being is a person". Effectively, he was looking for equal treatment and civil rights for blacks within the French Union

rather than independence, at least for the time being. He demarginalised large masses of people—women, youth, workers, poor cultivators—with the intent of unleashing the creativity of the Oubanguian people by placing them centre stage in the making of their country's history.

The movement was more popular among villagers than among évolué

townsmen, whom Boganda considered servile and to whom he applied the derogatory term "Mboundjou-Voko" ("Black-Whites"). Additionally, he created the Intergroupe Liberal Oubanguien (ILO) in 1953, which aimed to elect an equal number of black and white politicians to the assembly, so that a united electoral college

could be established. MESAN's activities angered the French administration and the companies trading in cotton, coffee, diamonds and other commodities. The Bangui chamber of commerce was controlled by these companies, and the men who gathered at this club strongly resented the demise of forced labour and the resultant rise of black nationalism. They hated Boganda in particular, viewing him as a dangerous revolutionary demagogue and a threat to their "free enterprise", and they resolved to get rid of him. They also set up local RPF

branches to counter MESAN, and the presence of African Democratic Rally (RDA) in the other three territories of French Equatorial Africa posed some menace for MESAN, but by 1958, although other parties were allowed, they had been reduced to tiny groups. On many occasions, General Charles de Gaulle

expressed his sympathy for Oubangui-Chari, which had supported de Gaulle's Free French Forces

as early as August 1940, and refused to support the violent intrigues of the RPF against Boganda and his men. He received Boganda, by then head of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and pushing for independence, in Paris in July 1958 and was in turn received at Brazzaville in August. The discussions there led to the General accepting Boganda's demands for independence and the endorsement of the French Community

in September throughout French Equatorial Africa

.

Boganda's attachment to his chosen calling weakened when he met and fell in love with a young Frenchwoman, Michelle Jourdain, who was employed as a parliamentary secretary. They were married on 13 June 1950, for which Boganda was expelled from the priesthood and cut off from the Catholic hierarchy's support. Boganda and Jourdain would later have two daughters and a son. The affair caused a minor scandal in Paris, but it did little to dent his popularity with his people. In the National Assembly he continued to battle, often in vain, against repressive features of the French administration in Oubangui-Chari. Arbitrary arrest, low wages, compulsory cotton cultivation, and the exclusion of blacks from restaurants and cinemas were all targets of his rhetoric.

to the National Assembly with 48% of the vote despite the obstacles placed in his way by the administration and strong opposition by the authorities, colonists, and the missions, with two prominent French candidates seeking to oust him. At this time, he emerged as an extraordinarily popular messianic folk hero and his country's leading nationalist; MESAN became the majority party in the Territorial Assembly elections

in March 1952. In this period he divided his time between his coffee plantation, his emancipation work and new political positions. In April 1954, an incident that would showcase Boganda's talent and appeal with crowds erupted at Berbérati

. A white public works agent, who had recently been reprimanded for his brutality toward Africans, announced that his cook and the cook's wife had died. A riot broke out and the governor sent in parachutists while armoured vehicles patrolled the streets. Boganda hesitated to appear in a village that was not one of his strongholds, but did so anyway and declared before the rioters that justice would be the same for blacks and whites. Upon hearing Boganda's words, the crowd became calm and dispersed.

He played a crucial role at the beginning of internal autonomy (1956–1958), although the relatively conservative Boganda remained sympathetic to French interests and still did not advocate immediate independence. For Boganda, the 1956 election, in which he took 89% of the vote against another Oubanguian, was an uncontested speaker's platform with which the colonial administration had come to terms; the French had realised that opposing him would be dangerous and sought to accommodate him. That year he agreed to European representation on election lists in exchange for the financial support of French business leaders, and on 18 November, was elected as the first mayor of Bangui. On 31 March 1957, MESAN won all seats in the Territorial Assembly election

He played a crucial role at the beginning of internal autonomy (1956–1958), although the relatively conservative Boganda remained sympathetic to French interests and still did not advocate immediate independence. For Boganda, the 1956 election, in which he took 89% of the vote against another Oubanguian, was an uncontested speaker's platform with which the colonial administration had come to terms; the French had realised that opposing him would be dangerous and sought to accommodate him. That year he agreed to European representation on election lists in exchange for the financial support of French business leaders, and on 18 November, was elected as the first mayor of Bangui. On 31 March 1957, MESAN won all seats in the Territorial Assembly election

; on 18 June, Boganda was elected president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa (a forum he used to broadcast his views on African unity) and in May was appointed vice-president of the Oubangui-Chari Government Council (the French governor was still its president).

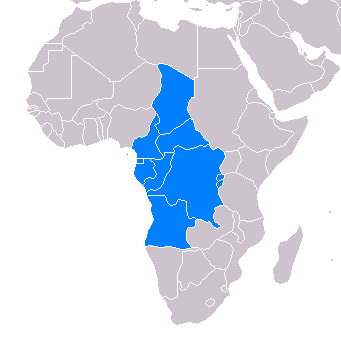

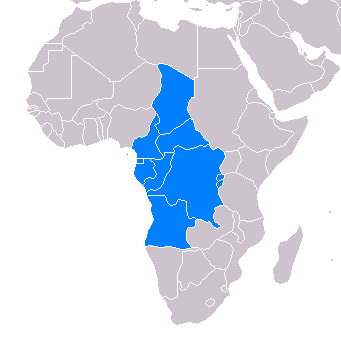

A pragmatist, Boganda spoke before the local assembly on 30 December 1957 in praise of the new Comité de Salut Economique, which envisioned joint administration of the economy between French colonials and MESAN territorial councilors (he called it "the union of capital and Oubanguian labour"), but lack of French investment and opposition by Oubanguians soon led him to turn away from the idea. With the numerous declarations of independence being made in much of Francophone Africa, Boganda advised that an independent Oubangui-Chari would face major economic problems from the onset. Instead, he advocated the independence of all of French Equatorial Africa

and its integration into a United States of Latin Africa

comprising the former French, Belgian, and Portuguese

colonies of Central Africa; he intended for Oubangui-Chari to become a federal unit within that structure. However, such a federation proved unrealistic, foundering on the rocks of regional jealousy and personal ambition, and Boganda came to accept a constitution covering only Oubangui-Chari as the Central African Republic. Thus, after 1 December 1958, when Boganda declared the establishment of the Central African Republic as an autonomous member of the French Community, the name was applied only to the former Oubangui-Chari. On 8 December, the CAR's first government came into being with Boganda as prime minister; a French governor remained in the country but was now called high commissioner. The new government began by adopting a law banning nudity and vagabondage, Boganda's missionary education still showing through. Its main task, however, was to draw up a constitution, which was democratic and modelled to some extent on that of France; this was approved by the assembly on 16 February 1959. Formal independence came later, on 13 August 1960.

of Boda (about 160 kilometres (99.4 mi) west of Bangui), killing all passengers and crew. No clear cause has ever been ascertained for the mysterious crash and no commission of inquiry was ever formed; sabotage was widely suspected. The nation was shocked at the death of its revered leader, whose funeral on April 2 at the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Bangui saw a great outpouring of grief from thousands of Oubanguians. The 7 May edition of the Paris weekly L'Express

revealed that experts had found traces of explosive in the wreckage, but the French high commissioner banned the sale of that magazine edition when it appeared in the CAR. Many suspected that expatriate businessmen from the Bangui chamber of commerce, possibly aided by the French secret service, played a role. Michelle Jourdain was suspected of being involved, as well: by 1959, relations between Boganda and his wife had deteriorated, and he thought of leaving her and returning to the priesthood. She had a large insurance policy on his life, taken just days before the accident. According to Brian Titley, author of Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, there are good reasons for suspecting her involvement in the plane crash.

Abel Goumba

, the vice-premier and finance minister whom Titley describes as "intelligent, honest, and strongly nationalistic", emerged as Boganda's logical successor. However, his close confidant and cousin, interior minister David Dacko

, more likely to lead a regime deferential to foreign interests, was backed by the high commissioner, Colonel Roger Barberot, with the support of the chamber of commerce and Michelle Jourdain. He thus brushed aside Goumba and by 1962 had shut down the opposition, with MESAN becoming the country's single party. The events after Boganda's death are strongly evocative of other French efforts to maintain economic domination by ensuring that compliant leaders came to power in its former colonies. It also robbed the country of a charismatic leader in the Houphouët-Boigny

or Senghor

mould, whose prestige alone might have sufficed to retain civilian rule, which ended when Bokassa deposed the unpopular Dacko in 1966.

Boganda is not only considered the hero and father of his nation but also as one of the great leaders of Black African emancipation; the historian Georges Chaffard described him after his death as "the most prestigious and the most capable of Equatorial political men," while political historian Gérard Prunier

Boganda is not only considered the hero and father of his nation but also as one of the great leaders of Black African emancipation; the historian Georges Chaffard described him after his death as "the most prestigious and the most capable of Equatorial political men," while political historian Gérard Prunier

called him "probably the most gifted and most inventive of French Africa's decolonization generation of politicians." Among the places named after him are an avenue in Bangui, one of the city's largest high schools, a Château Boganda and Barthelemy Boganda Stadium

. March 29, the anniversary of his death, is Boganda Day, a public holiday. Boganda was also the designer of the Flag of the Central African Republic

, originally intended for the United States of Latin Africa

.

Boganda is one in a long line of African political leaders who, in an attempt to develop specifically national political cultures, were presented (or presented themselves) as the great national leader, glorified and sometimes nearly deified. They were hailed as the fathers of their nations and considered wise in the ways of understanding the best interests of their peoples. Others who became particular objects of hero-worship include Léopold Sédar Senghor

, Félix Houphouët-Boigny

, Moktar Ould Daddah

, Ahmed Sékou Touré

, Modibo Keïta

, Léon M'ba

and Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly

. Boganda did little to discourage wide circulation of tales about his supernatural powers, putative invulnerability and even immortality. Shortly before his death, a large crowd waited on the shore of the Ubangui River to see him cross by walking upon the waters. He did not show up, but apparently a good many people still believed that he could have made the miraculous crossing. More than just a charismatic political leader, he was seen as the "black Christ", a great religious figure endowed with extraordinary powers. Along with Congo-Brazzaville

's Fulbert Youlou

, who remained a priest while president, Boganda was not particularly concerned with his religious mission once he entered politics, but he unabashedly used the enormous popular respect for the Church and the cloth to political advantage. He successfully manipulated religious symbols (clerical garb, crosses, baptism, disciples, acolytes, etc.) for political purposes.

Once he died, his mystique grew: he was a national martyr, and miracles were regularly attributed to him. The Boganda myth continues to exercise a strong hold on many people in the CAR, and it has frequently been used by his successors in their appeals for national unity. Those who were related to him even tenuously, such as Bokassa (who was from the same village and minority ethnic group, was the son of his mother's uncle, justified his coup using Boganda's name and created a cult of Boganda as founder of the party and state), or Dacko (who posed as the ideological successor of Boganda by championing for "national reconciliation" during the 1981 election

) were able to capture some of his aura and use it to their advantage.

|-

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

politician of what is now the Central African Republic

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic , is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Chad in the north, Sudan in the north east, South Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south, and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of about ,...

. Boganda was active prior to his country's independence, during the period when the area, part of French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

, was administered by France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

under the name of Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari, or Ubangi-Shari, was a French territory in central Africa which later became the independent Central African Republic . French activity in the area began in 1889 with the establishment of an outpost at Bangui, now the capital of CAR. The territory was named in 1894.In 1903, French...

. He served as the first Prime Minister of the Central African Republic autonomous territory.

Boganda was born into a family of subsistence farmers, and was adopted and educated by Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

missionaries

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

. In 1938, he was ordained as the first Roman Catholic priest from Oubangui-Chari. During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Boganda served in a number of missions and after was persuaded by the Bishop of Bangui

Bangui

-Law and government:Bangui is an autonomous commune of the Central African Republic. With an area of 67 km², it is by far the smallest high-level administrative division of the CAR in area but the highest in population...

to enter politics. In 1946, he became the first Oubanguian elected to the French National Assembly, where he maintained a political platform

Party platform

A party platform, or platform sometimes also referred to as a manifesto, is a list of the actions which a political party, individual candidate, or other organization supports in order to appeal to the general public for the purpose of having said peoples' candidates voted into political office or...

against racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

and the colonial regime

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

. He then returned to Oubangui-Chari to form a grassroots movement in opposition of French colonialism

French colonial empires

The French colonial empire was the set of territories outside Europe that were under French rule primarily from the 17th century to the late 1960s. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second-largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire...

. The movement led to the foundation of the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa

MESAN

The Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire was a nationalist quasi-religious political party that sought to affirm black humanity and advocated for the independence of Ubangi-Shari, then a French colonial territory...

(MESAN), and became popular among villagers and the working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

. Boganda's reputation was slightly damaged when he was laicized

Defrocking

To defrock, unfrock, or laicize ministers or priests is to remove their rights to exercise the functions of the ordained ministry. This may be due to criminal convictions, disciplinary matters, or disagreements over doctrine or dogma...

from the priesthood after marrying Michelle Jourdain, a parliamentary secretary. Nonetheless, he continued to advocate for equal treatment and civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

for blacks in the territory well into the 1950s.

In 1958, after the French Fourth Republic

French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic was the republican government of France between 1946 and 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution. It was in many ways a revival of the Third Republic, which was in place before World War II, and suffered many of the same problems...

began to consider granting independence to most of its African colonies, Boganda met with Prime Minister

Prime Minister of France

The Prime Minister of France in the Fifth Republic is the head of government and of the Council of Ministers of France. The head of state is the President of the French Republic...

Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

to discuss terms for the independence of Oubangui-Chari. De Gaulle accepted Boganda's terms, and on 1 December, Boganda declared the establishment of the Central African Republic. He became the autonomous territory's first Prime Minister and intended to serve as the first President of the independent CAR. He was killed in a mysterious plane crash on 29 March 1959, while en route to Bangui. Experts found a trace of explosives in the plane's wreckage, but revelation of this detail was withheld. Although those responsible for the crash were never identified, people have suspected the French secret service, and even Boganda's wife, of being involved. Slightly more than one year later, Boganda's dream was realized, when the Central African Republic attained formal independence from France.

Early life

Boganda was born to a family of subsistence farmersSubsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture is self-sufficiency farming in which the farmers focus on growing enough food to feed their families. The typical subsistence farm has a range of crops and animals needed by the family to eat and clothe themselves during the year. Planting decisions are made with an eye...

in Bobangui

Bobangui

Bobangui is a large M'Baka village in Lobaye, Central African Republic, located at the edge of the equatorial forest some southwest of the capital, Bangui. Both President Barthélemy Boganda and Jean-Bédel Bokassa were born in this village....

, a large M'Baka

M'Baka

The M'baka are a minority people in the Central African Republic and northwest Democratic Republic of Congo. The former President and Emperor, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, was M'Baka, as was the CAR's first President, David Dacko and Prime Minister Barthélémy Boganda...

village in the Lobaye

Lobaye

Lobaye is one of the 14 prefectures of the Central African Republic. Its capital is Mbaïki. The prefecture is located in the southern part of the country, bordering the Congo Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

basin located at the edge of the equatorial forest some 80 kilometres (49.7 mi) southwest of Bangui

Bangui

-Law and government:Bangui is an autonomous commune of the Central African Republic. With an area of 67 km², it is by far the smallest high-level administrative division of the CAR in area but the highest in population...

. French commercial exploitation of Central Africa had reached an apogee around the time of Boganda's birth, and although interrupted by World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, activity resumed in the 1920s. The French consortia used what was essentially a form of slavery—the corvée—and one of the most notorious was the Compagnie forestière de la Sangha-Oubangui, involved in rubber gathering in the Lobaye district.

In the late 1920s, Boganda's mother was beaten to death by the company's officials while collecting rubber in the forest. His uncle, whose son Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa , a military officer, was the head of state of the Central African Republic and its successor state, the Central African Empire, from his coup d'état on 1 January 1966 until 20 September 1979...

would later crown himself as the Emperor of the Central African Empire

Central African Empire

The Central African Empire was a short-lived, self-declared autocratic monarchy that replaced the Central African Republic and was, in turn, replaced by the restoration of the republic. The empire was formed when Jean-Bédel Bokassa, President of the republic, declared himself Emperor Bokassa I on...

, was beaten to death at the colonial police station as a result of his alleged resistance to work

Employment

Employment is a contract between two parties, one being the employer and the other being the employee. An employee may be defined as:- Employee :...

. Boganda's father was a witch doctor

Witch doctor

A witch doctor originally referred to a type of healer who treated ailments believed to be caused by witchcraft. It is currently used to refer to healers in some third world regions, who use traditional healing rather than contemporary medicine...

who had engaged in cannibalistic

Cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh of other human beings. It is also called anthropophagy...

rituals.

During his early years, Boganda was adopted by Catholic missionaries. As a boy he attended the school opened at Mbaiki

Mbaïki

Mbaïki is the capital of Lobaye, one of the 14 prefectures of the Central African Republic. It situated in the southwest of the country, 107 km from the capital Bangui. The economy is based on the coffee and timber industries. Lobaye people and Pygmy people live in the area. There is also a...

(the administrative centre for the Lobaye prefecture

Prefecture

A prefecture is an administrative jurisdiction or subdivision in any of various countries and within some international church structures, and in antiquity a Roman district governed by an appointed prefect.-Antiquity:...

) by the post's founder, Lieutenant Mayer. From December 1921 to December 1922, he spent two hours a day with Monsignor

Monsignor

Monsignor, pl. monsignori, is the form of address for those members of the clergy of the Catholic Church holding certain ecclesiastical honorific titles. Monsignor is the apocopic form of the Italian monsignore, from the French mon seigneur, meaning "my lord"...

Jean-Réné Calloch learning how to read, while spending the rest of his time performing manual labour. On December 24, he was received into the church under the name Barthélemy, in honour of one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ who was believed to have worked as Christian missionary

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

in Africa. Father Gabriel Herrau sent Boganda to the Catholic School of Betou and then to the school of the Saint Paul Mission at Bangui, where he completed his primary studies under Mgr Calloch, whom he would consider his spiritual father. The missionaries there, encouraged by his intellectual promise and pious demeanour, helped him continue secondary studies at small seminaries in Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

and Kisantu

Kisantu

Kisantu, also known as Inkisi, is a town in the western Democratic Republic of Congo, lying south west of Kinshasa, on the Inkisi River. It is known for its large cathedral and for its botanical gardens, which include an arboretum of indigenous trees....

(under Belgian

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

Jesuits

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

) before he moved on to the great seminary at Yaoundé

Yaoundé

-Transportation:Yaoundé Nsimalen International Airport is a major civilian hub, while nearby Yaoundé Airport is used by the military. Railway lines run west to the port city of Douala and north to N'Gaoundéré. Many bus companies operate from the city; particularly in the Nsam and Mvan neighborhoods...

. On 17 March 1938, fulfilling an ambition he had had since age twelve, he was ordained and became the first Roman Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

priest native to Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari, or Ubangi-Shari, was a French territory in central Africa which later became the independent Central African Republic . French activity in the area began in 1889 with the establishment of an outpost at Bangui, now the capital of CAR. The territory was named in 1894.In 1903, French...

, as the colony was then called. He ministered at Bangui, Grimari

Grimari

Grimari is a city located in the Ouaka prefecture in Central African Republic, approximately away from capital, Bangui. President Abel Goumba was born in this city.-External links:***...

and Bangassou

Bangassou

Bangassou is a city in the south eastern Central African Republic, lying on the north bank of the Mbomou River. It has a population of 24,447 and is the capital of the Mbomou prefecture. It is known for its wildlife and its market and is linked by ferry to the Democratic Republic of Congo on the...

, and in 1939, his bishop denied his request to join the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

. He was needed at home, as many Frenchmen involved with the church had been called back to the metropole to fight in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, during which he served in a number of missions.

Beginnings in politics and marriage

After World War II, Boganda was urged by the Bishop of Bangui, Mgr Grandin, to complement his humanitarian and social works through political action. Boganda decided to run for election to the National Assembly of France. On 10 November 1946, he became the first Oubanguian electedFrench legislative election, November 1946

Legislative election was held in France on 10 November 1946 to elect the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. The electoral system used was proportional representation....

to the assembly after winning almost half of the total votes cast and defeating three other candidates, including the outgoing incumbent, François Joseph Reste, who had formerly served as the Governor-General of French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

. Boganda arrived in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

attired in his clerical garb and introduced himself to his fellow legislators as the son of a polygamous cannibal. From 1947 on, Boganda conducted a lively campaign against racism and the colonial regime. Soon realizing the limits of his influence in France (he served in parliament until 1958 but gradually detached himself from its activities), he returned to Oubangui-Chari to organise a grassroots movement of teachers, truck drivers and small producers to oppose French colonialism, although his previous attempt to set up a marketing cooperative among African planters of his own ethnicity had failed. On 28 September 1949, at Bangui, he founded the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN), a quasi-religious political movement

Political movement

A political movement is a social movement in the area of politics. A political movement may be organized around a single issue or set of issues, or around a set of shared concerns of a social group...

and party

Political party

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to influence government policy, usually by nominating their own candidates and trying to seat them in political office. Parties participate in electoral campaigns, educational outreach or protest actions...

that sought to affirm black humanity and quickly came to dominate local politics. His political creed was summed up in the Sango

Sango language

Sango is the primary language spoken in the Central African Republic: it has approximately 1,600,000 second-language speakers, but only about 404,000 native speakers, mainly in the towns.- Classification :...

phrase "zo kwe zo", which translated to "every human being is a person". Effectively, he was looking for equal treatment and civil rights for blacks within the French Union

French Union

The French Union was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial system, the "French Empire" and to abolish its "indigenous" status.-History:...

rather than independence, at least for the time being. He demarginalised large masses of people—women, youth, workers, poor cultivators—with the intent of unleashing the creativity of the Oubanguian people by placing them centre stage in the making of their country's history.

The movement was more popular among villagers than among évolué

Évolué

Évolué is a French term used in the colonial era to refer to native Africans and Asians who had "evolved", through education or assimilation, and accepted European values and patterns of behavior...

townsmen, whom Boganda considered servile and to whom he applied the derogatory term "Mboundjou-Voko" ("Black-Whites"). Additionally, he created the Intergroupe Liberal Oubanguien (ILO) in 1953, which aimed to elect an equal number of black and white politicians to the assembly, so that a united electoral college

Electoral college

An electoral college is a set of electors who are selected to elect a candidate to a particular office. Often these represent different organizations or entities, with each organization or entity represented by a particular number of electors or with votes weighted in a particular way...

could be established. MESAN's activities angered the French administration and the companies trading in cotton, coffee, diamonds and other commodities. The Bangui chamber of commerce was controlled by these companies, and the men who gathered at this club strongly resented the demise of forced labour and the resultant rise of black nationalism. They hated Boganda in particular, viewing him as a dangerous revolutionary demagogue and a threat to their "free enterprise", and they resolved to get rid of him. They also set up local RPF

Rally of the French People

The Rally of the French People was a French political party, led by Charles de Gaulle.-Foundation:...

branches to counter MESAN, and the presence of African Democratic Rally (RDA) in the other three territories of French Equatorial Africa posed some menace for MESAN, but by 1958, although other parties were allowed, they had been reduced to tiny groups. On many occasions, General Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

expressed his sympathy for Oubangui-Chari, which had supported de Gaulle's Free French Forces

Free French Forces

The Free French Forces were French partisans in World War II who decided to continue fighting against the forces of the Axis powers after the surrender of France and subsequent German occupation and, in the case of Vichy France, collaboration with the Germans.-Definition:In many sources, Free...

as early as August 1940, and refused to support the violent intrigues of the RPF against Boganda and his men. He received Boganda, by then head of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and pushing for independence, in Paris in July 1958 and was in turn received at Brazzaville in August. The discussions there led to the General accepting Boganda's demands for independence and the endorsement of the French Community

French Community

The French Community was an association of states known in French simply as La Communauté. In 1958 it replaced the French Union, which had itself succeeded the French colonial empire in 1946....

in September throughout French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

.

Boganda's attachment to his chosen calling weakened when he met and fell in love with a young Frenchwoman, Michelle Jourdain, who was employed as a parliamentary secretary. They were married on 13 June 1950, for which Boganda was expelled from the priesthood and cut off from the Catholic hierarchy's support. Boganda and Jourdain would later have two daughters and a son. The affair caused a minor scandal in Paris, but it did little to dent his popularity with his people. In the National Assembly he continued to battle, often in vain, against repressive features of the French administration in Oubangui-Chari. Arbitrary arrest, low wages, compulsory cotton cultivation, and the exclusion of blacks from restaurants and cinemas were all targets of his rhetoric.

Increasing popularity and move toward autonomy

On 29 March 1951, Boganda was sentenced to two months in prison following his arrest on 10 January for "endangering the peace" after intervening in a local market dispute (the "Bokanga incident" in Lobaye). His wife was sentenced to 15 days in prison, but neither served their terms. On 17 June, he was re-electedFrench legislative election, 1951

Legislative elections were held in France on 17 June 1951 to elect the second National Assembly of the Fourth Republic.After the Second World War, the three parties which took a major part in the French Resistance to the German occupation dominated the political scene and government: the French...

to the National Assembly with 48% of the vote despite the obstacles placed in his way by the administration and strong opposition by the authorities, colonists, and the missions, with two prominent French candidates seeking to oust him. At this time, he emerged as an extraordinarily popular messianic folk hero and his country's leading nationalist; MESAN became the majority party in the Territorial Assembly elections

Ubangi-Shari parliamentary election, 1952

Territorial Assembly elections were held in Ubangi-Shari in March 1952. The result was a victory for the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa , which won 17 seats .-Results:...

in March 1952. In this period he divided his time between his coffee plantation, his emancipation work and new political positions. In April 1954, an incident that would showcase Boganda's talent and appeal with crowds erupted at Berbérati

Berbérati

Berbérati is the third-largest city in the Central African Republic with a population of 76,918 . It is the capital of the Mambéré-Kadéï Prefecture. The city is situated in the south-west of the country near the border with Cameroon...

. A white public works agent, who had recently been reprimanded for his brutality toward Africans, announced that his cook and the cook's wife had died. A riot broke out and the governor sent in parachutists while armoured vehicles patrolled the streets. Boganda hesitated to appear in a village that was not one of his strongholds, but did so anyway and declared before the rioters that justice would be the same for blacks and whites. Upon hearing Boganda's words, the crowd became calm and dispersed.

Ubangi-Shari parliamentary election, 1957

Territorial Assembly elections were held in Ubangi-Shari on 31 March 1957. The first and second college system for giving separate seats to Europeans and Africans was scrapped, and all 50 seats elected by universal suffrage. The result was a victory for the Movement for the Social Evolution of...

; on 18 June, Boganda was elected president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa (a forum he used to broadcast his views on African unity) and in May was appointed vice-president of the Oubangui-Chari Government Council (the French governor was still its president).

A pragmatist, Boganda spoke before the local assembly on 30 December 1957 in praise of the new Comité de Salut Economique, which envisioned joint administration of the economy between French colonials and MESAN territorial councilors (he called it "the union of capital and Oubanguian labour"), but lack of French investment and opposition by Oubanguians soon led him to turn away from the idea. With the numerous declarations of independence being made in much of Francophone Africa, Boganda advised that an independent Oubangui-Chari would face major economic problems from the onset. Instead, he advocated the independence of all of French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

and its integration into a United States of Latin Africa

United States of Latin Africa

The United States of Latin Africa was the proposed union of Romance-language-speaking African countries envisioned by Barthélémy Boganda...

comprising the former French, Belgian, and Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

colonies of Central Africa; he intended for Oubangui-Chari to become a federal unit within that structure. However, such a federation proved unrealistic, foundering on the rocks of regional jealousy and personal ambition, and Boganda came to accept a constitution covering only Oubangui-Chari as the Central African Republic. Thus, after 1 December 1958, when Boganda declared the establishment of the Central African Republic as an autonomous member of the French Community, the name was applied only to the former Oubangui-Chari. On 8 December, the CAR's first government came into being with Boganda as prime minister; a French governor remained in the country but was now called high commissioner. The new government began by adopting a law banning nudity and vagabondage, Boganda's missionary education still showing through. Its main task, however, was to draw up a constitution, which was democratic and modelled to some extent on that of France; this was approved by the assembly on 16 February 1959. Formal independence came later, on 13 August 1960.

Death and aftermath

Boganda was poised to become the first president of the independent CAR when he boarded a plane at Berbérati for a flight to Bangui on 29 March 1959, just prior to legislative elections. The aircraft exploded in midair over Boukpayanga in the sub-prefectureSub-prefectures of the Central African Republic

The prefectures of the Central African Republic are divided into 71 sub-prefectures . The sub-prefectures are listed below, by prefecture.-Bamingui-Bangoran Prefecture:* Bamingui* Ndélé-Bangui Commune:* Bangui...

of Boda (about 160 kilometres (99.4 mi) west of Bangui), killing all passengers and crew. No clear cause has ever been ascertained for the mysterious crash and no commission of inquiry was ever formed; sabotage was widely suspected. The nation was shocked at the death of its revered leader, whose funeral on April 2 at the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Bangui saw a great outpouring of grief from thousands of Oubanguians. The 7 May edition of the Paris weekly L'Express

L'Express (France)

L'Express is a French weekly news magazine. When founded in 1953 during the First Indochina War, it was modelled on the US magazine TIME.-History:...

revealed that experts had found traces of explosive in the wreckage, but the French high commissioner banned the sale of that magazine edition when it appeared in the CAR. Many suspected that expatriate businessmen from the Bangui chamber of commerce, possibly aided by the French secret service, played a role. Michelle Jourdain was suspected of being involved, as well: by 1959, relations between Boganda and his wife had deteriorated, and he thought of leaving her and returning to the priesthood. She had a large insurance policy on his life, taken just days before the accident. According to Brian Titley, author of Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, there are good reasons for suspecting her involvement in the plane crash.

Abel Goumba

Abel Goumba

Abel Nguéndé Goumba was a Central African political figure...

, the vice-premier and finance minister whom Titley describes as "intelligent, honest, and strongly nationalistic", emerged as Boganda's logical successor. However, his close confidant and cousin, interior minister David Dacko

David Dacko

David Dacko was the first President of the Central African Republic , from August 14, 1960 to January 1, 1966, and the third president of the CAR from September 21, 1979 to September 1, 1981...

, more likely to lead a regime deferential to foreign interests, was backed by the high commissioner, Colonel Roger Barberot, with the support of the chamber of commerce and Michelle Jourdain. He thus brushed aside Goumba and by 1962 had shut down the opposition, with MESAN becoming the country's single party. The events after Boganda's death are strongly evocative of other French efforts to maintain economic domination by ensuring that compliant leaders came to power in its former colonies. It also robbed the country of a charismatic leader in the Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny , affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux, was the first President of Côte d'Ivoire. Originally a village chief, he worked as a doctor, an administrator of a plantation, and a union leader, before being elected to the French Parliament and serving in a number of...

or Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor was a Senegalese poet, politician, and cultural theorist who for two decades served as the first president of Senegal . Senghor was the first African elected as a member of the Académie française. Before independence, he founded the political party called the Senegalese...

mould, whose prestige alone might have sufficed to retain civilian rule, which ended when Bokassa deposed the unpopular Dacko in 1966.

Legacy

Gérard Prunier

Gérard Prunier is a French academic and historian specializing in the Horn of Africa and East Africa.Prunier received a PhD in African History in 1981 from the University of Paris. In 1984, he joined the CNRS scientific institution in Paris as a researcher. He later also became Director of the...

called him "probably the most gifted and most inventive of French Africa's decolonization generation of politicians." Among the places named after him are an avenue in Bangui, one of the city's largest high schools, a Château Boganda and Barthelemy Boganda Stadium

Barthelemy Boganda Stadium

Complexe Sportif Barthelemy Boganda in Bangui is the national stadium of the Central African Republic. It is currently used mostly for football matches. The stadium has a capacity of 20,000 people. It is named after the former president of the country, Barthelemy Boganda.-External links:*...

. March 29, the anniversary of his death, is Boganda Day, a public holiday. Boganda was also the designer of the Flag of the Central African Republic

Flag of the Central African Republic

The flag of the Central African Republic was adopted on December 1, 1958. It was designed by Barthélemy Boganda, the first president of the autonomous territory of Oubangui-Chari, who believed that "France and Africa must march together." Thus he combined the blue, white and red of the French...

, originally intended for the United States of Latin Africa

United States of Latin Africa

The United States of Latin Africa was the proposed union of Romance-language-speaking African countries envisioned by Barthélémy Boganda...

.

Boganda is one in a long line of African political leaders who, in an attempt to develop specifically national political cultures, were presented (or presented themselves) as the great national leader, glorified and sometimes nearly deified. They were hailed as the fathers of their nations and considered wise in the ways of understanding the best interests of their peoples. Others who became particular objects of hero-worship include Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor was a Senegalese poet, politician, and cultural theorist who for two decades served as the first president of Senegal . Senghor was the first African elected as a member of the Académie française. Before independence, he founded the political party called the Senegalese...

, Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny , affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux, was the first President of Côte d'Ivoire. Originally a village chief, he worked as a doctor, an administrator of a plantation, and a union leader, before being elected to the French Parliament and serving in a number of...

, Moktar Ould Daddah

Moktar Ould Daddah

Moktar Ould Daddah was the President of Mauritania from 1960, when his country gained its independence from France, to 1978, when he was deposed in a military coup d'etat.- Background :...

, Ahmed Sékou Touré

Ahmed Sékou Touré

Ahmed Sékou Touré was an African political leader and President of Guinea from 1958 to his death in 1984...

, Modibo Keïta

Modibo Keïta

Modibo Keita ; was the first President of Mali and the Prime Minister of the Mali Federation. He espoused a form of African socialism.-Youth:...

, Léon M'ba

Léon M'ba

Gabriel Léon M'ba was the first Prime Minister and President of Gabon. A member of the Fang ethnic group, M'ba was born into a relatively privileged village family. After studying at a seminary, he held a number of small jobs before entering the colonial administration as a customs agent...

and Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly

Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly

Daniel Ouezzin Coulibaly was the president of the governing council of the French colony of Upper Volta, today's Burkina Faso, from 17 May 1957 until his death on 7 September 1958 in Paris...

. Boganda did little to discourage wide circulation of tales about his supernatural powers, putative invulnerability and even immortality. Shortly before his death, a large crowd waited on the shore of the Ubangui River to see him cross by walking upon the waters. He did not show up, but apparently a good many people still believed that he could have made the miraculous crossing. More than just a charismatic political leader, he was seen as the "black Christ", a great religious figure endowed with extraordinary powers. Along with Congo-Brazzaville

Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo , sometimes known locally as Congo-Brazzaville, is a state in Central Africa. It is bordered by Gabon, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo , the Angolan exclave province of Cabinda, and the Gulf of Guinea.The region was dominated by...

's Fulbert Youlou

Fulbert Youlou

Abbé Fulbert Youlou was a Brazzaville-Congolese Roman Catholic priest, nationalist leader and politician.-Early life:...

, who remained a priest while president, Boganda was not particularly concerned with his religious mission once he entered politics, but he unabashedly used the enormous popular respect for the Church and the cloth to political advantage. He successfully manipulated religious symbols (clerical garb, crosses, baptism, disciples, acolytes, etc.) for political purposes.

Once he died, his mystique grew: he was a national martyr, and miracles were regularly attributed to him. The Boganda myth continues to exercise a strong hold on many people in the CAR, and it has frequently been used by his successors in their appeals for national unity. Those who were related to him even tenuously, such as Bokassa (who was from the same village and minority ethnic group, was the son of his mother's uncle, justified his coup using Boganda's name and created a cult of Boganda as founder of the party and state), or Dacko (who posed as the ideological successor of Boganda by championing for "national reconciliation" during the 1981 election

Central African Republic presidential election, 1981

Presidential elections were held in the Central African Republic on 15 March 1981. Five candidates—David Dacko, Ange-Félix Patassé, François Pehoua, Henri Maïdou and Abel Goumba—ran for the election....

) were able to capture some of his aura and use it to their advantage.

External links

Grioo.com biography|-