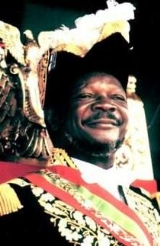

Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Encyclopedia

Jean-Bédel Bokassa a military officer, was the head of state

of the Central African Republic

and its successor state, the Central African Empire

, from his coup d'état

on 1 January 1966 until 20 September 1979. Of this period, he served almost eleven years (1 January 1966–4 December 1976) as president

(president for life

in 1972–1976), and for almost three years, 4 December 1976—20 September 1979), he reigned as emperor

. Although Bokassa was formally crowned in December 1977, his imperial title did not achieve worldwide diplomatic recognition.

After his overthrow in 1979, Central Africa reverted to its former name and status as the Central African Republic, and the former Bokassa I went into exile. He returned to Central Africa in 1986, was put on trial for treason and murder and convicted of these offenses in 1987, and was imprisoned in 1987—1993. Bokassa lived in private life in his former capital, Bangui, until his death in November 1996.

, a large M'Baka

village in the Lobaye

basin located at the edge of the equatorial forest, then a part of colonial French Equatorial Africa

, some 80 kilometres (49.7 mi) southwest of Bangui

. Mgboundoulou was forced to organise the rosters of his village people to work for the French Forestière company. After hearing about the efforts of a prophet named Karnu to resist French rule and forced labour, Mgboundoulou decided that he would no longer follow French orders. He released some of his fellow villagers who were being held hostage by the Forestière. The company considered this to be a rebellious act, so they detained Mgboundoulou, and took him away bound in chains to Mbaïki

. On 13 November 1927, he was beaten to death in the town square just outside the prefecture office. A week later, Bokassa's mother, Marie Yokowo, unable to bear the grief of losing her husband, committed suicide.

Bokassa's extended family decided that it would be best if he received a French-language education at the Ecole Sainte-Jeanne d'Arc, a Christian mission

school in Mbaïki. As a child, he was frequently taunted by his classmates about his orphanhood. He was short in stature and physically strong. In his studies, he became especially fond of a French grammar book by an author named Jean Bedel. His teachers noticed his attachment, and started calling him "Jean-Bedel". During his teenage years, Bokassa studied at Ecole Saint-Louis in Bangui, under Father Grüner. Grüner educated Bokassa with the intention of making him a priest, but realized that his student did not have the aptitude for study or the piety required for this occupation. He then studied at Father Compte's school in Brazzaville

, where he developed his abilities as a cook. After graduating in 1939, Bokassa took the advice offered to him by his grandfather, M'Balanga, and Father Grüner, by joining the Free French Forces

as a private

on 19 May.

in July 1940 and a sergeant major in November 1941. After the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, Bokassa served in the Forces' African unit and took part in the capture of the Vichy government's

capital at Brazzaville. On 15 August 1944, he participated in the Allied Forces

’ landing in Provence

, France, in Operation Dragoon

and fought in southern France and in Germany in early 1945 before Nazi Germany

was toppled. He remained in the French Army after the war, studying radio transmission

s at an army camp in the French coastal town of Fréjus

. Afterwards, he attended officer training

school in Saint-Louis, Senegal

. On 7 September 1950, Bokassa headed to Indochina

as the transmissions expert for the battalion of Saigon-Cholon

. Bokassa saw some combat during the First Indochina War

before his tour of duty

ended in March 1953. For his exploits in battle, he was honored with a membership in the Légion d'honneur

, and was decorated with Croix de guerre

. During his stay in Indochina, he married a 17-year-old Vietnamese girl named Nguyen Thi Hué. After Hué bore him a daughter, Bokassa had the child registered as a French national

. Bokassa left Indochina without his wife and child, as he believed he would return for another tour of duty in the near future. Upon his return to France, Bokassa was stationed at Fréjus, where he taught radio transmissions to African recruits. In 1956, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant

and two years later to Lieutenant

. Bokassa was then stationed as a military technical assistant in Brazzaville

and later Bangui

before being promoted to the rank of Captain

on 1 July 1961.

The French colony of Ubangi-Chari

(Oubangui-Chari in French), part of French Equatorial Africa

, had become a semi-autonomous territory of the French Community

in 1958 and then an independent nation as the Central African Republic

on 13 August 1960.

On 1 January 1962, Bokassa left the French Army

and joined the military forces of the CAR

with the rank of battalion commandant. As a cousin of the CAR President David Dacko

and nephew of Dacko's predecessor Barthélémy Boganda

, Bokassa was given the task of creating the new country's military. Over a year later, Bokassa became commander-in-chief

of the 500 soldiers in the Central African army. Due to his relation to Dacko and experience abroad in the French military, Bokassa was able to quickly rise through the ranks of the army, becoming the Central African army's first colonel on 1 December 1964.

Bokassa sought recognition for his status as leader of the army. He frequently appeared in public wearing all his military decorations, and in ceremonies, he often sat next to President Dacko to display his importance in the government. Bokassa frequently got into heated arguments with Jean-Paul Douate, the government's chief of protocol, who admonished him for not following the correct order of seating at presidential tables. At first, Dacko found his cousin's antics amusing. Despite the number of recent military coups in Africa, Dacko publicly dismissed the likelihood that Bokassa would try to take control of the country. At an official dinner, he said, "Colonel Bokassa only wants to collect medals and he is too stupid to pull off a coup d'état". Other members of Dacko's cabinet believed that Bokassa was a genuine threat to the regime. Jean-Arthur Bandio, the minister of interior, suggested Dacko name Bokassa to the Cabinet, which he hoped would both break the colonel's close connections with the CAR army and satisfy the colonel's desire for recognition. To combat the chance that Bokassa would stage a coup, Dacko created the gendarmerie

, an armed police force of 500 and a 120-member presidential security guard, led by Jean Izamo

and Prosper Mounoumbaye, respectively.

, the bureaucracy started to fall apart, and the country's boundaries were constantly breached by Lumumbists

from the south and the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army

from the east. Under pressure from political radicals in the Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire (Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa or MESAN

) and in an attempt to cultivate alternative sources of support and display his ability to make foreign policy without the help of the French government, Dacko established diplomatic relations with Mao Zedong

's People's Republic of China

(PRC) in September 1964. A delegation led by Meng Yieng and agents of the Chinese government toured the country, showing communist propaganda films

. Soon after, the PRC gave the CAR an interest-free loan of one billion CFA franc

s (20 million French franc

s); however, the aid failed to subdue the prospect of a financial collapse for the country. Widespread corruption

by government officials and politicians added to the country's list of problems. Bokassa felt that he needed to take over the CAR government to solve all the country's problems—most importantly, to rid the country from the influence of communism. According to Samuel Decalo, a scholar on African government, Bokassa's personal ambitions played the most important role in his decision to launch a coup against Dacko.

Dacko sent Bokassa to Paris as part of the country's delegation for the Bastille Day

celebrations in July 1965. After attending the celebrations and a 23 July ceremony to mark the closing of a military officer training school he had attended decades earlier, Bokassa decided to return to the CAR. However, Dacko forbade his return, and the infuriated Bokassa spent the next few months trying to obtain supporters from the French and Central African armed forces, who he hoped would force Dacko to reconsider his decision. Dacko eventually yielded to pressure and allowed Bokassa back in October 1965. Bokassa claimed that Dacko finally gave up after French President Charles de Gaulle

had personally told Dacko that "Bokassa must be immediately returned to his post. I cannot tolerate the mistreatment of my companion-in-arms".

Tensions between Dacko and Bokassa continued to escalate in the coming months. In December, Dacko approved an increase in the budget for Izamo's gendarmerie, but rejected the budget proposal Bokassa had made for the army. At this point, Bokassa told friends he was annoyed by Dacko's mistreatment and was "going for a coup d'état". Dacko planned to replace Bokassa with Izamo as his personal military adviser, and wanted to promote army officers loyal to the government, while demoting Bokassa and his close associates. Dacko did not conceal his plans; he hinted at his intentions to elders of the Bobangui

village, who in turn informed Bokassa of the plot. Bokassa realized he had to act against Dacko quickly, and worried that his 500-man army would be no match for the gendarmerie and the presidential guard. He was also overwrought over the possibility that the French would come to Dacko's aid after the coup d'état, as had occurred after one in Gabon

against President Léon M'ba

in February 1964. After receiving word of the coup from the country's vice president, officials in Paris sent paratrooper

s to Gabon in a matter of hours and M'Ba was quickly restored to power.

Bokassa received substantive support from his co-conspirator, Captain Alexandre Banza

, who commanded the Camp Kassaï military base in northeast Bangui, and, like Bokassa, had been stationed with the French army around the world. Banza was an intelligent, ambitious and capable man who played a major role in the planning of the coup. By December, many people began to anticipate the political turmoil that would soon engulf the country. Dacko's personal advisers alerted him that Bokassa "showed signs of mental instability" and needed to be arrested before he sought to bring down the government, but Dacko did not heed these warnings.

Dacko left the Palais de la Renaissance early in the evening of 31 December 1965 to visit one of his ministers' plantations southwest of Bangui. An hour and a half before midnight, Captain Banza gave orders to his officers to begin the coup. Bokassa called Izamo at his headquarters and asked him to come to Camp de Roux to sign some documents that needed his immediate attention. Izamo, who was at a New Year's Eve

Dacko left the Palais de la Renaissance early in the evening of 31 December 1965 to visit one of his ministers' plantations southwest of Bangui. An hour and a half before midnight, Captain Banza gave orders to his officers to begin the coup. Bokassa called Izamo at his headquarters and asked him to come to Camp de Roux to sign some documents that needed his immediate attention. Izamo, who was at a New Year's Eve

celebration with friends, reluctantly agreed and travelled to the camp. Upon arrival, he was confronted by Banza and Bokassa, who informed him of the coup in progress. After declaring his opposition to the coup, Izamo was taken by the coup plotters to an underground cellar

.

Around midnight, Bokassa, Banza and their supporters left Camp de Roux to take over the capital. After seizing the capital in a matter of hours, Bokassa and Banza rushed to the Palais de la Renaissance in order to arrest Dacko. However, Dacko was nowhere to be found. Bokassa panicked, believing the president had been warned of the coup in advance, and immediately ordered his soldiers to search for Dacko in the countryside until he was found. Dacko was arrested by soldiers patrolling Pétévo Junction, on the western border of the capital. He was taken back to the presidential palace, where Bokassa hugged the president and told him, "I tried to warn you—but now it's too late". President Dacko was taken to Ngaragba Prison in east Bangui at around 02:00 WAT (01:00 UTC). In a move that he thought would boost his popularity in the country, Bokassa ordered prison director Otto Sacher to release all prisoners in the jail. Bokassa then took Dacko to Camp Kassaï, where he forced the president to resign. Later, Bokassa's officers announced on Radio-Bangui that the Dacko government had been toppled and Bokassa had taken over control. In the morning, Bokassa addressed the public via Radio-Bangui:

was banned; tom-tom

playing was allowed only during the nights and weekends; and a "morality brigade" was formed in the capital to monitor bars and dance halls. Polygamy

, dowries

and female circumcision

were all abolished. Bokassa also opened a public transport

system in Bangui and subsidized the creation of two national orchestra

s.

Despite the positive changes in the country, Bokassa had difficulty obtaining international recognition for his new government. He tried to justify the coup by explaining that Izamo and communist Chinese agents were trying to take over the government and that he had to intervene to save the CAR from the influence of communism. He alleged that Chinese agents in the countryside had been training and arming locals to start a revolution, and on 6 January 1966, he dismissed the communist agents from the country and cut off diplomatic relations with China. Bokassa also believed that the coup was necessary in order to prevent further corruption in the government.

Bokassa first secured diplomatic recognition from President François Tombalbaye

of neighboring Chad

, whom he met in Bouca

, Ouham

. After Bokassa reciprocated by meeting Tombalbaye on 2 April 1966 along the southern border of Chad at Fort Archambault

, the two decided to help one another if either was in danger of losing power. Soon after, other African countries began to diplomatically recognize the new government. At first, the French government was reluctant to support the Bokassa regime, so Banza went to Paris to meet with French officials to convince them that the coup was necessary to save the country from turmoil. Bokassa met with Prime Minister Georges Pompidou

on 7 July 1966, but the French remained noncommittal in offering their support. After Bokassa threatened to withdraw from the franc monetary zone, President Charles de Gaulle decided to make an official visit to the CAR on 17 November 1966. To the Bokassa regime, this visit meant that the French had finally accepted the new changes in the country.

On 13 April 1968, in another one of his frequent cabinet reshuffles, Bokassa demoted Banza to minister of health, but let him remain in his position as minister of state. Cognizant of the president's intentions, Banza increased his vocalization of dissenting political views. A year later, after Banza made a number of remarks highly critical of Bokassa and his management of the economy, the president, perceiving an immediate threat to his power, removed him as his minister of state. Banza revealed his intention to stage a coup to Lieutenant Jean-Claude Mandaba, the commanding officer of Camp Kassaï, who he looked to for support. Mandaba went along with the plan, but his allegiance remained with Bokassa. When Banza contacted his co-conspirators on 8 April 1969, informing them that they would execute the coup the following day, Mandaba immediately phoned Bokassa and informed him of the plan. When Banza entered Camp Kassaï on 9 April 1969, he was ambushed by Mandaba and his soldiers. The men had to break Banza's arms before they could overpower and throw him into the trunk of a Mercedes

and take him directly to Bokassa. At his house in Berengo, Bokassa nearly beat Banza to death before Mandaba suggested that Banza be put on trial for appearance's sake.

On 12 April, Banza presented his case before a military tribunal

at Camp de Roux, where he admitted to his plan, but stated that he had not planned to kill Bokassa. He was sentenced to death

by firing squad

, taken to an open field behind Camp Kassaï, executed and buried in an unmarked grave

. The circumstances of Banza's death have been disputed. The American newsmagazine, Time

, reported that Banza "was dragged before a Cabinet meeting where Bokassa slashed him with a razor. Guards then beat Banza until his back was broken, dragged him through the streets of Bangui and finally shot him." The French daily evening newspaper Le Monde

reported that Banza was killed in circumstances "so revolting that it still makes one's flesh creep":

. He survived another coup attempt in December 1974. The following month, on 2 January, he relinquished the position of prime minister

to Elisabeth Domitien

. His domestic and foreign policies became increasingly unpredictable, leading to another assassination attempt at Bangui M'Poko International Airport

in February 1976.

aided Bokassa.

Also France supported Bokassa and dealt with him. In 1975, the French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

declared himself a "friend and family member" of Bokassa. By that time France supplied its former colony's regime with financial and military backing. In exchange, Bokassa frequently took d'Estaing on hunting trips in Central Africa and supplied France with uranium

, which was vital for France's nuclear energy and weapons

program in the Cold War

era.

The "friendly and fraternal" cooperation with France—according to Bokassa's own terms—reached its peak with the imperial coronation ceremony of Bokassa I on 4 December 1977. The French Defence Minister sent a battalion to secure the ceremony; he also lent 17 aircraft to the new Central African Empire's government, and even assigned French Navy personnel to support the orchestra. The coronation ceremony lasted for two days and cost 10 million GBP, more than annual budget of the Central African Republic. The ceremony was organized by French artist Jean-Pierre Dupont. Parisian jeweller Claude Bertrand made his crown, which included diamonds. Bokassa sat on a two-ton throne modeled in the shape of a large eagle made from solid gold.

On 10 October 1979, the Canard Enchaîné satirical newspaper reported that President Bokassa had offered the then Minister of Finance Valéry Giscard d'Estaing two diamonds in 1973. This soon became a major political scandal known as the Diamonds Affair, which contributed significantly to Giscard d'Estaing's losing his reelection bid. The Franco-Central African relationship drastically changed when France's Renseignements Généraux intelligence service learned of Bokassa's willingness to become a partner of Muammar al-Gaddafi

of Libya

. In early December 1979, the French council officially stopped all support to Bokassa.

After a meeting with Gaddafi in September 1976, Bokassa converted to Islam

and changed his name to Salah Eddine Ahmed Bokassa, but in December 1976 he converted back to Catholicism

. It is presumed that this was a ploy calculated to ensure ongoing Libyan financial aid. When no funds promised by Gaddafi were forthcoming, Bokassa abandoned his new faith. It also was incompatible with his plans to be crowned emperor in the Catholic cathedral in Bangui.

a monarchy

, the Central African Empire

. The following year, he issued an imperial constitution

, announced his conversion back to Catholicism

and had himself crowned "S.M.I. Bokassa 1er ", with S.M.I. standing for Sa Majesté Impériale: "His Imperial Majesty", in a formal coronation ceremony on 4 December 1977. Bokassa's full title was Empereur de Centrafrique par la volonté du peuple Centrafricain, uni au sein du parti politique national, le MESAN

("Emperor of Central Africa by the will of the Central African people, united within the national political party, the MESAN"). His regalia

, lavish coronation

ceremony and regime of the newly formed Central African Empire were largely inspired by Napoleon I

, who had converted the French Revolutionary Republic of which he was First Consul into the First French Empire. The coronation ceremony was estimated to cost his country roughly 20 million US dollars.

Bokassa attempted to justify his actions by claiming that creating a monarchy would help Central Africa "stand out" from the rest of the continent, and earn the world's respect. The 1977 coronation ceremony consumed one third of the CAE's (Central African Empire) annual budget and all of France's aid money for that year, but despite generous invitations, no foreign leaders attended the event. By this time, many people in the CAE and in the rest of the world thought Bokassa was insane, and the Western press, mostly in France, the UK, and USA, often compared his eccentric behavior and egotistical extravagance with that of Africa's other well-known eccentric dictator, Idi Amin

of Uganda

. Tenacious rumors that he occasionally consumed human flesh

were found unproven during his eventual trial.

Although Bokassa claimed that the new empire would be a constitutional monarchy

, no significant democratic reforms were made, and suppression of dissenters remained widespread. Torture was said to be especially rampant, with allegations that even Bokassa himself occasionally participated in beatings and executions.

s with Bokassa's image on them. Around 100 children were killed. Bokassa allegedly participated in the massacre, beating some of the children to death with his cane. However, the initial reports received by Amnesty International indicated only that the 100 or more school students who died actually suffocated or were beaten to death while being forced into a small jail cell following their arrest.

The massive worldwide press coverage which followed the deaths of the students opened the way for a successful coup which saw French troops (in "Opération Barracuda") invade the Central African Empire and restored former president David Dacko to power while Bokassa fled into exile by airplane to the Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire

) on 20 September 1979.

. Operation Barracuda began on the evening of 20 September and ended early the next morning. An undercover commando squad from the French intelligence agency SDECE (now DGSE), joined by Special Forces' 1st Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment

, or 1er RPIMa, led by Colonel Brancion-Rouge, landed by Transall and managed to secure the Bangui Mpoko airport with little resistance. Upon arrival of two more French military transport aircraft, containing over 300 French troops, a message was sent by Colonal Brancion-Rouge to Colonel Degenne to come in with his Barracudas (codename for eight Puma helicopters

and Transall aircraft), which took off from N'Djamena

military airport in neighbouring Chad

.

. Bokassa, who was visiting Libya on a state visit at the time, fled to Côte d'Ivoire

(Ivory Coast) where he spent four years living in Abidjan

. He then moved to France where he was allowed to settle in his Chateau d'Hardricourt

in the suburb of Paris. France gave him political asylum because of the French Foreign Legion

obligations.

During Bokassa's seven-year of exile, he wrote his memoirs after complaining that his French military pension was insufficient. But the French courts ordered that all 8,000 copies of the book be confiscated and destroyed after his publisher claimed that Bokassa said that he shared women with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who has been a frequent guest in the Central African Republic. Bokassa also claimed to have given Giscard a gift of diamonds worth around a quarter of a million dollars in 1973 while the French president was serving as finance minister. Giscard's next presidential reelection campaign failed in the wake of the scandal. Bokassa's presence in France proved embarrassing to many government ministers who supported him during his entire rule.

in December 1980 for the murder of numerous political rivals. However, he returned from exile in France on 24 October 1986. Bokassa was immediately arrested by the Central African authorities as soon as he stepped off the plane and was tried for 14 different charges, including treason

, murder, cannibalism

, illegal use of property, assault and battery, and embezzlement

. Now that Bokassa was unexpectedly in the hands of the Central African Republic government, they were required by law to try him in person, granting him the benefit of defence counsel.

The trial began on 15 December 1986, taking place in the hot and humid, non-air conditioned chambers of the Palais de Justice in Bangui. Bokassa hired two French lawyers, François Gilbault and Francis Szpiner, which faced a panel composed of six jurors and three judges, presided over by High Court Judge Edouard Franck, which was modelled after the legal system in France itself. A fair jury trial of a former head of state was unprecedented in the history of post-colonial Africa where previous dictators had been tried and executed after show trials. New, too, was public access to the trial which the courtroom was constantly filled with standing-room-only spectators as well as live French-language broadcasts by Radio Bangui and local TV news crews which was broadcast all over the country, as well as neighbouring French-speaking African countries. The trial was listened to and watched by all those in the Central African Republic and in neighbouring countries by those who had access to any type of radio or TV set.

The prosecutor was Gabriel-Faustin M'Boudou, the Chief Prosecutor of the CAR, who called various witnesses to testify against Bokassa, which included remembering victims ranging from political enemies to a newborn son of a palace guard commander who had been executed for attempting to kill Bokassa in 1978 when he was the self-proclaimed emperor. A hospital nurse testified that Bokassa was said to have killed the delivered child with an injection of poison.

Next, testimony came from 27 teenagers and young adults who were former school children who testified to being the only survivors of the 180 children who were arrested and died in April 1979 after they threw rocks at Bokassa's passing Rolls-Royce

during the students protest over wearing the costly school uniforms which they were forced to purchase from a factory owned by one of his wives. Several of them testified that on their first night in jail, Bokassa visited the prison and screamed at the children for their insolence. He was said to have ordered the prison guards to club the children to death, and Bokassa indeed participated, smashing the skulls of at least five children with his ebony walking stick.

Throughout the entire trial, Bokassa denied all the charges against him. He attempted to shift the blame away from himself to wayward members of his former cabinet and the army for any misdeeds that might have occurred during his reign as both president and emperor. Testifying in his own defence, Bokassa stated: "I'm not a saint. I'm just a man like everyone else." As testimony against him mounted, he gave away at several times his legendary short temper. Bokassa once stood up and raged at chief prosecutor M'Boudou: "The aggravating thing about all this is that it's all about Bokassa, Bokassa, Bokassa! I have enough crimes levelled against me without you blaming me for all the murders of the last 21 years!"

One of the most lurid allegations against Bokassa was the charge of cannibalism, which was technically superfluous. In the Central African Republic, statutes forbidding cannibalism classified any crime of eating human remains as a misdemeanour. Upon seizing power from David Dacko in 1981, the current President André Kolingba

had declared amnesty for all misdemeanours committed during the tenure of his predecessors. Bokassa could not be punished for the crime, even if he was found guilty. The cannibalism charges against him were brought from old indictments in 1980 that resulted in his conviction in absentia, a year before Kolingba's amnesty, so the anthropophagy

charge remained listed among Bokassa's crimes.

Former president Dacko was called to the witness stand to testify that he had seen photographs of butchered bodies hanging in the dark cold-storage rooms of Bokassa's palace immediately after the 1979 coup. When the defence put up a reasonable doubt during the cross-examination of Dacko that he could not be positively sure if the photographs he had seen of dead bodies were used for consumption, Bokassa's former security chief of the palace was called to testify that he had cooked human flesh stored in the walk-in freezers and served it to Bokassa on an occasional basis. The prosecution did not examine the rumours that Bokassa had served the flesh of his victims to French President Giscard d'Estaing and other visiting dignitaries.

The government prosecutors hired Bernard Jouanneau, a French lawyer to investigate as well as recover some of the millions of CAR francs that Bokassa had diverted from the national treasury and from both social and charity funds for his own personal use in the embezzlement charges. Late in the trial, Bokassa's lawyers tried to bar Jouanneau from testifying. In light of the other heinous crimes Bokassa was charged with, the embezzlement indictment seemed almost insignificant, particularly since Bokassa had clearly already spent most of the money that was stolen.

On 12 June 1987, Bokassa was found guilty of all but the cannibalism charges. The court acknowledged that many individual allegations of murder had been levelled at Bokassa but found that the evidence was unimpeachable in only about 20 cases. Bokassa was said to have wept silently as Judge Franck sentenced him to death. Szpiner and Gibault appealed the verdict for a retrial on the grounds that the Central African Republic's constitution allowed a former head of state to be charged only with treason. The CAR supreme court rejected the appeal.

On 29 February 1988, President Kolingba demonstrated his opposition to capital punishment by voiding the death penalty against Bokassa and commuted his sentence to life in prison in solitary confinement, and the following year reduced the sentence to 20 years. With the return of democracy to the Central African Republic in 1993, Kolingba declared a general amnesty

for all prisoners as one of his final acts as President, and Bokassa was released on 1 August 1993.

Bokassa remained in the CAR for the rest of his life. In 1996, as his health declined, he proclaimed himself the 13th Apostle and claimed to have secret meetings with the Pope

. Bokassa died of a heart attack

on 3 November 1996 in Bangui, at the age of 75. He had 17 wives and a reported 50 children.

issued a decree rehabilitating Bokassa and calling him "a son of the nation recognised by all as a great builder". The decree went on to hold that "This rehabilitation of rights erases penal condemnations, particularly fines and legal costs, and stops any future incapacities that result from them". In the lead-up to this official rehabilitation, Bokassa has been praised by CAR politicians for his patriotism and for the periods of stability that he brought the country.

Bokassa the First, Emperor

of Central Africa

by the will of the Central African people, united within the national political party, the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa.

|-

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

of the Central African Republic

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic , is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Chad in the north, Sudan in the north east, South Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south, and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of about ,...

and its successor state, the Central African Empire

Central African Empire

The Central African Empire was a short-lived, self-declared autocratic monarchy that replaced the Central African Republic and was, in turn, replaced by the restoration of the republic. The empire was formed when Jean-Bédel Bokassa, President of the republic, declared himself Emperor Bokassa I on...

, from his coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

on 1 January 1966 until 20 September 1979. Of this period, he served almost eleven years (1 January 1966–4 December 1976) as president

President

A president is a leader of an organization, company, trade union, university, or country.Etymologically, a president is one who presides, who sits in leadership...

(president for life

President for Life

President for Life is a title assumed by some dictators to remove their term limit, in the hope that their authority, legitimacy, and term will never be disputed....

in 1972–1976), and for almost three years, 4 December 1976—20 September 1979), he reigned as emperor

Emperor

An emperor is a monarch, usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife or a woman who rules in her own right...

. Although Bokassa was formally crowned in December 1977, his imperial title did not achieve worldwide diplomatic recognition.

After his overthrow in 1979, Central Africa reverted to its former name and status as the Central African Republic, and the former Bokassa I went into exile. He returned to Central Africa in 1986, was put on trial for treason and murder and convicted of these offenses in 1987, and was imprisoned in 1987—1993. Bokassa lived in private life in his former capital, Bangui, until his death in November 1996.

Early life

Bokassa was born on 22 February 1921 as one of 12 children to Mindogon Mgboundoulou, a village chief, and his wife Marie Yokowo in BobanguiBobangui

Bobangui is a large M'Baka village in Lobaye, Central African Republic, located at the edge of the equatorial forest some southwest of the capital, Bangui. Both President Barthélemy Boganda and Jean-Bédel Bokassa were born in this village....

, a large M'Baka

M'Baka

The M'baka are a minority people in the Central African Republic and northwest Democratic Republic of Congo. The former President and Emperor, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, was M'Baka, as was the CAR's first President, David Dacko and Prime Minister Barthélémy Boganda...

village in the Lobaye

Lobaye

Lobaye is one of the 14 prefectures of the Central African Republic. Its capital is Mbaïki. The prefecture is located in the southern part of the country, bordering the Congo Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

basin located at the edge of the equatorial forest, then a part of colonial French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

, some 80 kilometres (49.7 mi) southwest of Bangui

Bangui

-Law and government:Bangui is an autonomous commune of the Central African Republic. With an area of 67 km², it is by far the smallest high-level administrative division of the CAR in area but the highest in population...

. Mgboundoulou was forced to organise the rosters of his village people to work for the French Forestière company. After hearing about the efforts of a prophet named Karnu to resist French rule and forced labour, Mgboundoulou decided that he would no longer follow French orders. He released some of his fellow villagers who were being held hostage by the Forestière. The company considered this to be a rebellious act, so they detained Mgboundoulou, and took him away bound in chains to Mbaïki

Mbaïki

Mbaïki is the capital of Lobaye, one of the 14 prefectures of the Central African Republic. It situated in the southwest of the country, 107 km from the capital Bangui. The economy is based on the coffee and timber industries. Lobaye people and Pygmy people live in the area. There is also a...

. On 13 November 1927, he was beaten to death in the town square just outside the prefecture office. A week later, Bokassa's mother, Marie Yokowo, unable to bear the grief of losing her husband, committed suicide.

Bokassa's extended family decided that it would be best if he received a French-language education at the Ecole Sainte-Jeanne d'Arc, a Christian mission

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

school in Mbaïki. As a child, he was frequently taunted by his classmates about his orphanhood. He was short in stature and physically strong. In his studies, he became especially fond of a French grammar book by an author named Jean Bedel. His teachers noticed his attachment, and started calling him "Jean-Bedel". During his teenage years, Bokassa studied at Ecole Saint-Louis in Bangui, under Father Grüner. Grüner educated Bokassa with the intention of making him a priest, but realized that his student did not have the aptitude for study or the piety required for this occupation. He then studied at Father Compte's school in Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

, where he developed his abilities as a cook. After graduating in 1939, Bokassa took the advice offered to him by his grandfather, M'Balanga, and Father Grüner, by joining the Free French Forces

Free French Forces

The Free French Forces were French partisans in World War II who decided to continue fighting against the forces of the Axis powers after the surrender of France and subsequent German occupation and, in the case of Vichy France, collaboration with the Germans.-Definition:In many sources, Free...

as a private

Private (rank)

A Private is a soldier of the lowest military rank .In modern military parlance, 'Private' is shortened to 'Pte' in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and to 'Pvt.' in the United States.Notably both Sir Fitzroy MacLean and Enoch Powell are examples of, rare, rapid career...

on 19 May.

Army

While serving in the Second bataillon de marche, Bokassa became a corporalCorporal

Corporal is a rank in use in some form by most militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. It is usually equivalent to NATO Rank Code OR-4....

in July 1940 and a sergeant major in November 1941. After the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, Bokassa served in the Forces' African unit and took part in the capture of the Vichy government's

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

capital at Brazzaville. On 15 August 1944, he participated in the Allied Forces

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

’ landing in Provence

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

, France, in Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon was the Allied invasion of southern France on August 15, 1944, during World War II. The invasion was initiated via a parachute drop by the 1st Airborne Task Force, followed by an amphibious assault by elements of the U.S. Seventh Army, followed a day later by a force made up...

and fought in southern France and in Germany in early 1945 before Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

was toppled. He remained in the French Army after the war, studying radio transmission

Transmission (telecommunications)

Transmission, in telecommunications, is the process of sending, propagating and receiving an analogue or digital information signal over a physical point-to-point or point-to-multipoint transmission medium, either wired, optical fiber or wireless...

s at an army camp in the French coastal town of Fréjus

Fréjus

Fréjus is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.It neighbours Saint-Raphaël, effectively forming one town...

. Afterwards, he attended officer training

Officer training

Officer training refers to the training that most military officers must complete before acquiring an officer rank. A potential recruit becomes an officer cadet, someone in training. An officer in training can either be trained in a military college like West Point, or taken from the enlisted ranks...

school in Saint-Louis, Senegal

Saint-Louis, Senegal

Saint-Louis, or Ndar as it is called in Wolof, is the capital of Senegal's Saint-Louis Region. Located in the northwest of Senegal, near the mouth of the Senegal River, and 320 km north of Senegal's capital city Dakar, it has a population officially estimated at 176,000 in 2005. Saint-Louis...

. On 7 September 1950, Bokassa headed to Indochina

Indochina

The Indochinese peninsula, is a region in Southeast Asia. It lies roughly southwest of China, and east of India. The name has its origins in the French, Indochine, as a combination of the names of "China" and "India", and was adopted when French colonizers in Vietnam began expanding their territory...

as the transmissions expert for the battalion of Saigon-Cholon

Cholon, Ho Chi Minh City

Chợ Lớn is a Chinese-influenced section of Ho Chi Minh City . It is the largest Chinatown in Vietnam. It lies on the west bank of the Saigon River, having Binh Tay Market as its central market. Cholon consists of the western half of District 5 as well as several adjoining neighborhoods in District...

. Bokassa saw some combat during the First Indochina War

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War was fought in French Indochina from December 19, 1946, until August 1, 1954, between the French Union's French Far East...

before his tour of duty

Tour of duty

In the Navy, a tour of duty is a period of time spent performing operational duties at sea, including combat, performing patrol or fleet duties, or assigned to service in a foreign country....

ended in March 1953. For his exploits in battle, he was honored with a membership in the Légion d'honneur

Légion d'honneur

The Legion of Honour, or in full the National Order of the Legion of Honour is a French order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Consulat which succeeded to the First Republic, on 19 May 1802...

, and was decorated with Croix de guerre

Croix de guerre

The Croix de guerre is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was awarded during World War I, again in World War II, and in other conflicts...

. During his stay in Indochina, he married a 17-year-old Vietnamese girl named Nguyen Thi Hué. After Hué bore him a daughter, Bokassa had the child registered as a French national

Nationality

Nationality is membership of a nation or sovereign state, usually determined by their citizenship, but sometimes by ethnicity or place of residence, or based on their sense of national identity....

. Bokassa left Indochina without his wife and child, as he believed he would return for another tour of duty in the near future. Upon his return to France, Bokassa was stationed at Fréjus, where he taught radio transmissions to African recruits. In 1956, he was promoted to Second Lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

and two years later to Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

. Bokassa was then stationed as a military technical assistant in Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

and later Bangui

Bangui

-Law and government:Bangui is an autonomous commune of the Central African Republic. With an area of 67 km², it is by far the smallest high-level administrative division of the CAR in area but the highest in population...

before being promoted to the rank of Captain

Captain (OF-2)

The army rank of captain is a commissioned officer rank historically corresponding to command of a company of soldiers. The rank is also used by some air forces and marine forces. Today a captain is typically either the commander or second-in-command of a company or artillery battery...

on 1 July 1961.

The French colony of Ubangi-Chari

Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari, or Ubangi-Shari, was a French territory in central Africa which later became the independent Central African Republic . French activity in the area began in 1889 with the establishment of an outpost at Bangui, now the capital of CAR. The territory was named in 1894.In 1903, French...

(Oubangui-Chari in French), part of French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

, had become a semi-autonomous territory of the French Community

French Community

The French Community was an association of states known in French simply as La Communauté. In 1958 it replaced the French Union, which had itself succeeded the French colonial empire in 1946....

in 1958 and then an independent nation as the Central African Republic

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic , is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Chad in the north, Sudan in the north east, South Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south, and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of about ,...

on 13 August 1960.

On 1 January 1962, Bokassa left the French Army

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

and joined the military forces of the CAR

Military of the Central African Republic

The Forces armées centrafricaines are the armed forces of the Central African Republic, established after independence in 1960. Today they are a rather weak institution, dependent on international support to hold back the enemies in the current civil war...

with the rank of battalion commandant. As a cousin of the CAR President David Dacko

David Dacko

David Dacko was the first President of the Central African Republic , from August 14, 1960 to January 1, 1966, and the third president of the CAR from September 21, 1979 to September 1, 1981...

and nephew of Dacko's predecessor Barthélémy Boganda

Barthélemy Boganda

Barthélemy Boganda was the leading nationalist politician of what is now the Central African Republic. Boganda was active prior to his country's independence, during the period when the area, part of French Equatorial Africa, was administered by France under the name of Oubangui-Chari...

, Bokassa was given the task of creating the new country's military. Over a year later, Bokassa became commander-in-chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

of the 500 soldiers in the Central African army. Due to his relation to Dacko and experience abroad in the French military, Bokassa was able to quickly rise through the ranks of the army, becoming the Central African army's first colonel on 1 December 1964.

Bokassa sought recognition for his status as leader of the army. He frequently appeared in public wearing all his military decorations, and in ceremonies, he often sat next to President Dacko to display his importance in the government. Bokassa frequently got into heated arguments with Jean-Paul Douate, the government's chief of protocol, who admonished him for not following the correct order of seating at presidential tables. At first, Dacko found his cousin's antics amusing. Despite the number of recent military coups in Africa, Dacko publicly dismissed the likelihood that Bokassa would try to take control of the country. At an official dinner, he said, "Colonel Bokassa only wants to collect medals and he is too stupid to pull off a coup d'état". Other members of Dacko's cabinet believed that Bokassa was a genuine threat to the regime. Jean-Arthur Bandio, the minister of interior, suggested Dacko name Bokassa to the Cabinet, which he hoped would both break the colonel's close connections with the CAR army and satisfy the colonel's desire for recognition. To combat the chance that Bokassa would stage a coup, Dacko created the gendarmerie

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

, an armed police force of 500 and a 120-member presidential security guard, led by Jean Izamo

Jean Izamo

Jean-Henri Izamo was the head of the gendarmerie of the Central African Republic. He was killed following the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état.-Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état:...

and Prosper Mounoumbaye, respectively.

Tensions rise between Dacko and Bokassa

Dacko's government faced a number of problems during 1964 and 1965: the economy experienced stagnationEconomic stagnation

Economic stagnation or economic immobilism, often called simply stagnation or immobilism, is a prolonged period of slow economic growth , usually accompanied by high unemployment. Under some definitions, "slow" means significantly slower than potential growth as estimated by experts in macroeconomics...

, the bureaucracy started to fall apart, and the country's boundaries were constantly breached by Lumumbists

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis...

from the south and the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army

Sudan People's Liberation Army

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement is a political party in South Sudan. It was initially founded as a rebel political movement with a military wing known as the Sudan People's Liberation Army estimated at 180,000 soldiers. The SPLM fought in the Second Sudanese Civil War against the Sudanese...

from the east. Under pressure from political radicals in the Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire (Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa or MESAN

MESAN

The Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire was a nationalist quasi-religious political party that sought to affirm black humanity and advocated for the independence of Ubangi-Shari, then a French colonial territory...

) and in an attempt to cultivate alternative sources of support and display his ability to make foreign policy without the help of the French government, Dacko established diplomatic relations with Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

's People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

(PRC) in September 1964. A delegation led by Meng Yieng and agents of the Chinese government toured the country, showing communist propaganda films

Propaganda in the People's Republic of China

Propaganda in the People's Republic of China as interpreted in Western media refers to the Communist Party of China's use of propaganda to sway public and international opinion in favor of its policies. Domestically, this includes censorship of proscribed views and an active cultivation of views...

. Soon after, the PRC gave the CAR an interest-free loan of one billion CFA franc

CFA franc

The CFA franc is the name of two currencies used in Africa which are guaranteed by the French treasury. The two CFA franc currencies are the West African CFA franc and the Central African CFA franc...

s (20 million French franc

French franc

The franc was a currency of France. Along with the Spanish peseta, it was also a de facto currency used in Andorra . Between 1360 and 1641, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money...

s); however, the aid failed to subdue the prospect of a financial collapse for the country. Widespread corruption

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

by government officials and politicians added to the country's list of problems. Bokassa felt that he needed to take over the CAR government to solve all the country's problems—most importantly, to rid the country from the influence of communism. According to Samuel Decalo, a scholar on African government, Bokassa's personal ambitions played the most important role in his decision to launch a coup against Dacko.

Dacko sent Bokassa to Paris as part of the country's delegation for the Bastille Day

Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the name given in English-speaking countries to the French National Day, which is celebrated on 14 July of each year. In France, it is formally called La Fête Nationale and commonly le quatorze juillet...

celebrations in July 1965. After attending the celebrations and a 23 July ceremony to mark the closing of a military officer training school he had attended decades earlier, Bokassa decided to return to the CAR. However, Dacko forbade his return, and the infuriated Bokassa spent the next few months trying to obtain supporters from the French and Central African armed forces, who he hoped would force Dacko to reconsider his decision. Dacko eventually yielded to pressure and allowed Bokassa back in October 1965. Bokassa claimed that Dacko finally gave up after French President Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

had personally told Dacko that "Bokassa must be immediately returned to his post. I cannot tolerate the mistreatment of my companion-in-arms".

Tensions between Dacko and Bokassa continued to escalate in the coming months. In December, Dacko approved an increase in the budget for Izamo's gendarmerie, but rejected the budget proposal Bokassa had made for the army. At this point, Bokassa told friends he was annoyed by Dacko's mistreatment and was "going for a coup d'état". Dacko planned to replace Bokassa with Izamo as his personal military adviser, and wanted to promote army officers loyal to the government, while demoting Bokassa and his close associates. Dacko did not conceal his plans; he hinted at his intentions to elders of the Bobangui

Bobangui

Bobangui is a large M'Baka village in Lobaye, Central African Republic, located at the edge of the equatorial forest some southwest of the capital, Bangui. Both President Barthélemy Boganda and Jean-Bédel Bokassa were born in this village....

village, who in turn informed Bokassa of the plot. Bokassa realized he had to act against Dacko quickly, and worried that his 500-man army would be no match for the gendarmerie and the presidential guard. He was also overwrought over the possibility that the French would come to Dacko's aid after the coup d'état, as had occurred after one in Gabon

Gabon

Gabon , officially the Gabonese Republic is a state in west central Africa sharing borders with Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, and with the Republic of the Congo curving around the east and south. The Gulf of Guinea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean is to the west...

against President Léon M'ba

Léon M'ba

Gabriel Léon M'ba was the first Prime Minister and President of Gabon. A member of the Fang ethnic group, M'ba was born into a relatively privileged village family. After studying at a seminary, he held a number of small jobs before entering the colonial administration as a customs agent...

in February 1964. After receiving word of the coup from the country's vice president, officials in Paris sent paratrooper

Paratrooper

Paratroopers are soldiers trained in parachuting and generally operate as part of an airborne force.Paratroopers are used for tactical advantage as they can be inserted into the battlefield from the air, thereby allowing them to be positioned in areas not accessible by land...

s to Gabon in a matter of hours and M'Ba was quickly restored to power.

Bokassa received substantive support from his co-conspirator, Captain Alexandre Banza

Alexandre Banza

Lieutenant Colonel Alexandre Banza was a military officer and politician in the Central African Republic. Born in Carnot, Ubangi-Shari, Banza served with the French Army during the First Indochina War before joining the Central African Republic armed forces...

, who commanded the Camp Kassaï military base in northeast Bangui, and, like Bokassa, had been stationed with the French army around the world. Banza was an intelligent, ambitious and capable man who played a major role in the planning of the coup. By December, many people began to anticipate the political turmoil that would soon engulf the country. Dacko's personal advisers alerted him that Bokassa "showed signs of mental instability" and needed to be arrested before he sought to bring down the government, but Dacko did not heed these warnings.

Coup d'état

New Year's Eve

New Year's Eve is observed annually on December 31, the final day of any given year in the Gregorian calendar. In modern societies, New Year's Eve is often celebrated at social gatherings, during which participants dance, eat, consume alcoholic beverages, and watch or light fireworks to mark the...

celebration with friends, reluctantly agreed and travelled to the camp. Upon arrival, he was confronted by Banza and Bokassa, who informed him of the coup in progress. After declaring his opposition to the coup, Izamo was taken by the coup plotters to an underground cellar

Basement

__FORCETOC__A basement is one or more floors of a building that are either completely or partially below the ground floor. Basements are typically used as a utility space for a building where such items as the furnace, water heater, breaker panel or fuse box, car park, and air-conditioning system...

.

Around midnight, Bokassa, Banza and their supporters left Camp de Roux to take over the capital. After seizing the capital in a matter of hours, Bokassa and Banza rushed to the Palais de la Renaissance in order to arrest Dacko. However, Dacko was nowhere to be found. Bokassa panicked, believing the president had been warned of the coup in advance, and immediately ordered his soldiers to search for Dacko in the countryside until he was found. Dacko was arrested by soldiers patrolling Pétévo Junction, on the western border of the capital. He was taken back to the presidential palace, where Bokassa hugged the president and told him, "I tried to warn you—but now it's too late". President Dacko was taken to Ngaragba Prison in east Bangui at around 02:00 WAT (01:00 UTC). In a move that he thought would boost his popularity in the country, Bokassa ordered prison director Otto Sacher to release all prisoners in the jail. Bokassa then took Dacko to Camp Kassaï, where he forced the president to resign. Later, Bokassa's officers announced on Radio-Bangui that the Dacko government had been toppled and Bokassa had taken over control. In the morning, Bokassa addressed the public via Radio-Bangui:

Early years of regime

In the early days of his regime, Bokassa engaged in self-promotion before the local media, showing his countrymen his French army medals, and displaying his strength, fearlessness and masculinity. He formed a new government called the Revolutionary Council, invalidated the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly. He called it "a lifeless organ no longer representing the people". In his address to the nation, Bokassa claimed that the government would hold elections in the future, a new assembly would be formed, and a new constitution would be written. He also told his countrymen that he would give up his power after the communist threat had been eliminated, the economy stabilized, and corruption rooted out. President Bokassa allowed MESAN to continue functioning, but barred all other political organizations from the country. In the coming months, Bokassa imposed a number of new rules and regulations: men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 had to provide proof that they had jobs, or else they would be fined or imprisoned; beggingBegging

Begging is to entreat earnestly, implore, or supplicate. It often occurs for the purpose of securing a material benefit, generally for a gift, donation or charitable donation...

was banned; tom-tom

Tom-tom drum

A tom-tom drum is a cylindrical drum with no snare.Although "tom-tom" is the British term for a child's toy drum, the name came originally from the Anglo-Indian and Sinhala; the tom-tom itself comes from Asian or Native American cultures...

playing was allowed only during the nights and weekends; and a "morality brigade" was formed in the capital to monitor bars and dance halls. Polygamy

Polygamy

Polygamy is a marriage which includes more than two partners...

, dowries

Dowry

A dowry is the money, goods, or estate that a woman brings forth to the marriage. It contrasts with bride price, which is paid to the bride's parents, and dower, which is property settled on the bride herself by the groom at the time of marriage. The same culture may simultaneously practice both...

and female circumcision

Female genital cutting

Female genital mutilation , also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is defined by the World Health Organization as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."FGM...

were all abolished. Bokassa also opened a public transport

Public transport

Public transport is a shared passenger transportation service which is available for use by the general public, as distinct from modes such as taxicab, car pooling or hired buses which are not shared by strangers without private arrangement.Public transport modes include buses, trolleybuses, trams...

system in Bangui and subsidized the creation of two national orchestra

Orchestra

An orchestra is a sizable instrumental ensemble that contains sections of string, brass, woodwind, and percussion instruments. The term orchestra derives from the Greek ορχήστρα, the name for the area in front of an ancient Greek stage reserved for the Greek chorus...

s.

Despite the positive changes in the country, Bokassa had difficulty obtaining international recognition for his new government. He tried to justify the coup by explaining that Izamo and communist Chinese agents were trying to take over the government and that he had to intervene to save the CAR from the influence of communism. He alleged that Chinese agents in the countryside had been training and arming locals to start a revolution, and on 6 January 1966, he dismissed the communist agents from the country and cut off diplomatic relations with China. Bokassa also believed that the coup was necessary in order to prevent further corruption in the government.

Bokassa first secured diplomatic recognition from President François Tombalbaye

François Tombalbaye

François Tombalbaye, also called Ngarta Tombalbaye , was a teacher and a trade union activist who served as the first president of Chad. He was born in the southern region of the country in the Moyen-Chari Prefecture near the city of Koumara and was of the Sara ethnic group, the prominent ethnicity...

of neighboring Chad

Chad

Chad , officially known as the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west...

, whom he met in Bouca

Bouca

Bouca is a town located in the Central African Republic prefecture of Ouham. It is not far east of Bossangoa at the Fafa river....

, Ouham

Ouham

Ouham is one of the 14 prefectures of the Central African Republic. Its capital is Bossangoa.-Geography:The prefecture is in the nord-west of the Central African Republic. In the north it has a border with the Chad. In the south is the prefecture Ombella-Mpoko, in the west the prefecture...

. After Bokassa reciprocated by meeting Tombalbaye on 2 April 1966 along the southern border of Chad at Fort Archambault

Sarh

Sarh is the third largest city in Chad, after N'Djamena and Moundou. It is the capital of Moyen-Chari region and the department of Barh Köh. It lies 350 miles south-east of the capital Ndjamena on the Chari River...

, the two decided to help one another if either was in danger of losing power. Soon after, other African countries began to diplomatically recognize the new government. At first, the French government was reluctant to support the Bokassa regime, so Banza went to Paris to meet with French officials to convince them that the coup was necessary to save the country from turmoil. Bokassa met with Prime Minister Georges Pompidou

Georges Pompidou

Georges Jean Raymond Pompidou was a French politician. He was Prime Minister of France from 1962 to 1968, holding the longest tenure in this position, and later President of the French Republic from 1969 until his death in 1974.-Biography:...

on 7 July 1966, but the French remained noncommittal in offering their support. After Bokassa threatened to withdraw from the franc monetary zone, President Charles de Gaulle decided to make an official visit to the CAR on 17 November 1966. To the Bokassa regime, this visit meant that the French had finally accepted the new changes in the country.

Threat to power

Bokassa and Banza had a major argument over the country's budget, as Banza adamantly opposed the president's extravagant spending. Bokassa moved to Camp de Roux, where he felt he could safely run the government without having to worry about Banza's thirst for power. In the meantime, Banza tried to obtain a support base within the army, spending much of his time in the company of soldiers. Bokassa recognized what his minister was doing, so he sent military units most sympathetic to Banza to the country's border and brought his own army supporters as close to the capital as possible. In September 1967, he took a special trip to Paris, where he asked for protection from French troops. Two months later, the government deployed 80 paratroopers to Bangui.On 13 April 1968, in another one of his frequent cabinet reshuffles, Bokassa demoted Banza to minister of health, but let him remain in his position as minister of state. Cognizant of the president's intentions, Banza increased his vocalization of dissenting political views. A year later, after Banza made a number of remarks highly critical of Bokassa and his management of the economy, the president, perceiving an immediate threat to his power, removed him as his minister of state. Banza revealed his intention to stage a coup to Lieutenant Jean-Claude Mandaba, the commanding officer of Camp Kassaï, who he looked to for support. Mandaba went along with the plan, but his allegiance remained with Bokassa. When Banza contacted his co-conspirators on 8 April 1969, informing them that they would execute the coup the following day, Mandaba immediately phoned Bokassa and informed him of the plan. When Banza entered Camp Kassaï on 9 April 1969, he was ambushed by Mandaba and his soldiers. The men had to break Banza's arms before they could overpower and throw him into the trunk of a Mercedes

Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz is a German manufacturer of automobiles, buses, coaches, and trucks. Mercedes-Benz is a division of its parent company, Daimler AG...

and take him directly to Bokassa. At his house in Berengo, Bokassa nearly beat Banza to death before Mandaba suggested that Banza be put on trial for appearance's sake.

On 12 April, Banza presented his case before a military tribunal

Military tribunal

A military tribunal is a kind of military court designed to try members of enemy forces during wartime, operating outside the scope of conventional criminal and civil proceedings. The judges are military officers and fulfill the role of jurors...

at Camp de Roux, where he admitted to his plan, but stated that he had not planned to kill Bokassa. He was sentenced to death

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

by firing squad

Execution by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, sometimes called fusillading , is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war.Execution by shooting is a fairly old practice...

, taken to an open field behind Camp Kassaï, executed and buried in an unmarked grave

Unmarked grave

The phrase unmarked grave has metaphorical meaning in the context of cultures that mark burial sites.As a figure of speech, a common meaning of the term "unmarked grave" is consignment to oblivion, i.e., an ignominious end. A grave monument is a sign of respect and fondness, erected with the...

. The circumstances of Banza's death have been disputed. The American newsmagazine, Time

Time (magazine)

Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

, reported that Banza "was dragged before a Cabinet meeting where Bokassa slashed him with a razor. Guards then beat Banza until his back was broken, dragged him through the streets of Bangui and finally shot him." The French daily evening newspaper Le Monde

Le Monde

Le Monde is a French daily evening newspaper owned by La Vie-Le Monde Group and edited in Paris. It is one of two French newspapers of record, and has generally been well respected since its first edition under founder Hubert Beuve-Méry on 19 December 1944...

reported that Banza was killed in circumstances "so revolting that it still makes one's flesh creep":

Rule during the 1970s

In 1971, Bokassa promoted himself to full general, and on March 4, 1972, declared himself president for lifePresident for Life

President for Life is a title assumed by some dictators to remove their term limit, in the hope that their authority, legitimacy, and term will never be disputed....

. He survived another coup attempt in December 1974. The following month, on 2 January, he relinquished the position of prime minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

to Elisabeth Domitien

Elisabeth Domitien

Elisabeth Domitien was prime minister of the Central African Republic from 1975 to 1976. She was the first and to date only woman to hold the position....

. His domestic and foreign policies became increasingly unpredictable, leading to another assassination attempt at Bangui M'Poko International Airport

Bangui M'Poko International Airport

-External links:* Afriqiyah Airways http://www.afriqiyah.aero* Official Airline Guide http://www.oag-flights.com...

in February 1976.

Foreign support

Muammar al-GaddafiMuammar al-Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar Gaddafi or "September 1942" 20 October 2011), commonly known as Muammar Gaddafi or Colonel Gaddafi, was the official ruler of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and then the "Brother Leader" of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011.He seized power in a...

aided Bokassa.

Also France supported Bokassa and dealt with him. In 1975, the French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing is a French centre-right politician who was President of the French Republic from 1974 until 1981...

declared himself a "friend and family member" of Bokassa. By that time France supplied its former colony's regime with financial and military backing. In exchange, Bokassa frequently took d'Estaing on hunting trips in Central Africa and supplied France with uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

, which was vital for France's nuclear energy and weapons

France and weapons of mass destruction

France is known to have an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. France is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty; but is not known to possess or develop any chemical or biological weapons. France was the fourth country to test an independently...

program in the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

era.