Beeching Axe

Encyclopedia

The Beeching Axe or the Beeching Cuts are informal names for the British Government's attempt in the 1960s to reduce the cost of running British Railways, the nationalised railway system in the United Kingdom

. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr

Richard Beeching

. Although this report also proposed new modes of freight service and the modernisation of trunk passenger routes, it is remembered for recommending wholesale closure of what it considered little-used and unprofitable railway lines, the removal of stopping passenger trains and closure of local stations on other lines that remained open.

The report was a reaction to significant losses that had begun in the 1950s as the expansion in road transport began to attract passengers and goods from the railways; losses which continued to bedevil British Railways despite the introduction of the railway Modernisation Plan of 1955. Beeching proposed that only drastic action would save the railways from increasing losses in the future.

Successive governments were more keen on the cost-saving elements of the report rather than those requiring investment. More than 4000 miles (6,437.4 km) of railway and 3,000 stations closed in the decade following the report, a reduction of 25 per cent of route miles and 50 per cent of stations. To this day, Beeching's name is unfavourably synonymous with mass closure of railways and loss of many local services. This is particularly so in parts of the country that suffered most from cuts.

After growing rapidly in the 19th century, the British railway system reached its height in the years immediately before the First World War. In 1913 there were 23,440 route miles (37,720 km) of railway.

After the war, the railways began to face competition from other modes of transport such as bus

es, car

s and road haulage. Because of this, a modest number of railway lines were closed during the 1920s and 1930s. Most of these early closures were of the most marginal country branch lines such as the Charnwood Forest Railway

, closed to passengers in 1931, and of short suburban lines that had fallen victim to competition from buses and tram

s, which offered a more frequent service. An example of this was the Harborne Line in Birmingham

, which closed to passengers in 1934.

Also, a number of lines had been built by rival companies between the same places to compete with each other. With the grouping of railway companies in 1923, many of these duplicating lines became redundant and were closed. In total 1264 miles (2,034.2 km) of railway were closed to passengers between 1923 and 1939.

With the onset of World War II

, the railways gained a reprieve as they became essential to the war effort

and were heavily used. By the time the railways were nationalised

in 1948, they were in a substantially worn down condition, as little maintenance or investment was carried out during the war.

(BTC) created the "Branch Lines Committee" in 1949, with a remit to close the least used branch lines. Many of the most minor and little-used lines were closed during this period, though some secondary cross-country lines were closed as well, such as the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway

in East Anglia

, which was closed in 1959. In total 3318 miles (5,339.8 km) of railway were closed between 1948 and 1962.

This period saw the beginnings of a closures protest movement led by the Railway Development Association, whose most famous member was the poet John Betjeman

.

with diesel

and electric locomotive

s. The plan promised to win back traffic and restore the railways to profit by 1962. Much of the Modernisation Plan was approved.

Traffic on the railways remained fairly steady during the 1950s, but the economics of the railway network steadily deteriorated. This was largely due to costs such as labour rising faster than income. Fares and freight charges were repeatedly frozen by the government in an attempt to control inflation

and please the electorate.

The result was that by 1955 income no longer covered operating costs, and the situation steadily worsened. Much of the money spent on the Modernisation Plan had been borrowed. By the early 1960s the railways were in financial crisis. Operating losses increased to £68m in 1960, £87m in 1961, and £104m in 1962 (£ as of ). The BTC could no longer pay interest on borrowed money, which worsened the financial problem. The government lost patience and looked for radical solutions.

In tune with the mood of the early 1960s, the transport minister in Harold Macmillan

's Conservative

government was Ernest Marples

, director of a road-construction company (his two-thirds shareholding was divested to his wife while he was a minister to avoid potential conflict of interests). Marples believed the future of transport lay with roads and that railways were a relic of the Victorian

past.

An advisory group, known as the Stedeford Committee after its chairman, Sir Ivan Stedeford

, was set up to report on the state of British transport and to provide recommendations. Also on the committee was Richard Beeching, at the time technical director of ICI

. He was later, in 1961, appointed chairman of the new British Railways Board. Stedeford and Beeching clashed on matters related to the latter's proposals to prune the rail infrastructure. In spite of questions in Parliament, Sir Ivan's report was published only much later, and the proposals for the future of the railways that came to be known as the Beeching Plan were adopted by the government, resulting in the closure of a third of the rail network and the scrapping of a third of a million freight wagons.

Beeching believed railways should be a business and not a public service, and that if parts of the railway system did not pay their way—like some rural branch lines—they should close. His reasoning was that once unprofitable lines were closed, the remaining system would be restored to profitability.

When Beeching was chairman of British Railways he initiated a study of traffic flows on all the railway lines in the country.

When Beeching was chairman of British Railways he initiated a study of traffic flows on all the railway lines in the country.

This study took place during the week ending 23 April 1962, two weeks after Easter, and concluded that 30 per cent of miles carried just 1 per cent of passengers and freight, and half of all stations contributed just 2 per cent of income.

The report The Reshaping of British Railways (or Beeching I report) of 27 March 1963 proposed that of Britain's 18000 miles (28,968.1 km) of railway, 6000 miles (9,656 km) of mostly rural branch and cross-country lines should close. Further, many other rail lines should be kept open for freight only, and many lesser-used stations should close on lines that were to be kept open. The report was accepted by the Government.

At the time, the controversial report was called the Beeching Bombshell or the Beeching Axe by the press. It sparked an outcry from communities that would lose their rail services, many of which (especially in the case of rural communities) had no other public transport.

The government argued that many services could be provided more cheaply by bus

es, and promised that abandoned rail services would have their places taken by bus services.

A significant part of the report proposed that British Rail electrify

some major main lines and adopt containerised freight traffic instead of outdated and uneconomic wagon-load traffic. Some of those plans were eventually adopted, such as the creation of the Freightliner

concept and further electrification of the West Coast Main Line

from Crewe

to Glasgow

in 1974. Additionally the staff terms and conditions were improved over time.

At its peak in 1950, British Railway's system was around 21000 miles (33,796.1 km) and 6,000 stations. By 1975, the system had shrunk to 12000 miles (19,312.1 km) of track and 2,000 stations; it has remained roughly this size thereafter.

Closures of unremunerative lines had been ongoing throughout the 20th century. Numbers increased in the 1950s, as the Branchline Committee of BR

also looked for uncontentious duplicated lines as candidates for closure. Approximately 3000 miles (4,828 km) of line had already been closed between nationalisation and the publication of Beeching's report. After publication, the closure process was accelerated markedly.

The list below shows 7000 miles of closures, compared to the 9,000 miles stated above, which may be partly explained by freight-only line closures.

such as the Far North Line

and the West Highland Line

, although listed for closure, were kept open, in part because of pressure from the powerful Highland lobby. The Central Wales Line

was said to have been kept open because it passed through so many marginal constituencies that no one dared to close it.

In addition, lines such as the Tamar Valley Line

in Devon

and Cornwall

were kept open because the local roads were poor.

Some lines not recommended for closure were eventually closed, such as the Woodhead Line

between Manchester and Sheffield in 1981, after the freight traffic (most notably coal) on which it had relied, declined.

In February 1965, the British Railways Board issued a second, less well-known, report The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes, informally known as Beeching II.

In February 1965, the British Railways Board issued a second, less well-known, report The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes, informally known as Beeching II.

This report identified lines which were believed to justify large-scale investment to meet the likely demand over the next 20 years. Some railway supporters assumed that any other line would be closed sooner or later, although the report itself was careful to explain that no decision had been taken about them. ("The purpose of this study is to select routes for future intensive use, not to select lines for closure...")

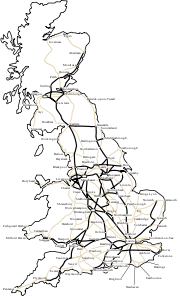

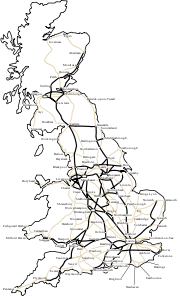

As the map shows, a small proportion of railway lines were highlighted. In Scotland only the Central Belt

routes and the lines via Fife and Perth to Aberdeen were selected for development, and none in Wales

at all, apart from the Great Western Main Line as far as Swansea. Many towns in south east England were not on selected lines, including places like Hastings and Eastbourne, although as the report also said that commuter routes would need "special consideration", major closures in the south east were probably the most unlikely of all.

In the event, this report does not seem to have made any lasting impression on the recently-elected Labour government, in power since October 1964, and Beeching resigned from BR two months after it was published.

Major railway closures may have been considered afresh since Beeching's time, but apart from the brief ripple caused by the Serpell Report

in 1982, they have not been formally proposed again.

Harold Wilson

. During the election campaign, Labour promised to halt the rail closures if elected. Once elected, they quickly backtracked on this promise, and the closures continued, at a faster rate than under the previous administration and until the end of the decade.

In 1965, Barbara Castle

was appointed transport minister and she decided that at least 11,000 route miles (17,700 km) would be needed for the foreseeable future and that the railway system should be stabilised at around this size.

Towards the end of the 1960s it became increasingly clear that rail closures were not producing the promised savings or bringing the rail system out of deficit and were unlikely ever to do so. Castle also stipulated that some rail services that could not pay their way but had a valuable social role should be subsidised. By the time the legislation allowing this was introduced into the 1968 Transport Act, (Section 39 of this Act made provision for a subsidy to be paid by the Treasury for a three-year period) many of the services and railway lines that would have qualified and benefited from these subsidies had already been closed or removed, thus lessening the impact of the legislation. Nevertheless, a number of branch lines were saved by this legislation.

The assumption at the time was that car

owners would drive to the nearest railhead (which was usually the junction where the closed branch line would otherwise have taken them) and continue their journey onwards by train. In practice having left home in their cars people used them for the whole journey. The same problem occurred with the movement of goods and freight: without branch lines, the railways' ability to transport goods "door to door" was dramatically reduced. Like the passenger model, it was assumed that lorries would pick up goods, transport them to the nearest railhead, where they would be taken across the country by train, unloaded onto another lorry and taken to their destination. The development of the motorway network, the advent of containerisation, improvements in road haulage vehicles, and the economic costs of having two break-of-bulk points all combined to make long-distance road transport a more viable alternative.

Another reason for Beeching plan's not achieving any great savings was that many of the closed lines ran at only a small deficit. Some lines such as the Sunderland

to West Hartlepool line cost only £291 per mile to operate. Closures of such small-scale loss making lines made little difference to the overall deficit. Perhaps ironically the busiest commuter routes had always lost the greatest amount of money, but even Beeching realised it would be impractical to close them.

The Beeching reports recommended against attempts to make loss-making lines profitable. Changes to light railway

services (already in use on some branch lines at the time of the report) were attacked by Beeching, who wrote: "The third suggestion, that rail buses should be substituted for trains, ignores the high cost of providing the route itself, and also ignores the fact that rail buses are more expensive vehicles than road buses." There is little in the Beeching report recommending general economies (in administration costs, working practices and so on). For example, a number of the stations that were closed were fully staffed eighteen hours a day, on lines controlled by multiple Victorian era

signalboxes (again fully staffed, often throughout the day). Reductions in operating costs could have been made by reducing staff and removing redundant services on these lines whilst still enabling these stations to stay open. Such concepts have since been successfully utilised by British Rail and its successors on lesser-used lines that survived the axe (such as the East Suffolk Line

from Ipswich to Lowestoft which survives as a "basic railway"). Such recommendations were absent from the Beeching reports.

In retrospect, many of the specific Beeching closures can be seen as very short-sighted. Many of the closed routes would now be heavily used, possibly even important trunk routes. The Settle-Carlisle Railway

was threatened with closure, reprieved and now handles more traffic (both passenger and freight) than at any time in its history. The Great Central Main Line

, the last trunk route built in Britain until the opening of High Speed 1 in 2007, was intended to provide a link to the north of England with a proposed Channel Tunnel

. It was built to the wider Continental loading gauge

and constructed to the same standards as a modern high speed line, with no level crossings and curves and gradients kept to an absolute minimum. This line closed in stages between 1966 and 1969 after just 60 years of service, 28 years before the eventual opening of the Channel Tunnel

rail link. Since the opening of the Channel Tunnel and High Speed 1, there has been discussion about "High Speed 2

" linking the tunnel to the North of England and Scotland. While this route would have been served by a simple extension of the closed line's original function, it would now be very difficult and expensive to construct as much of the former GCML route has been levelled or built on (see below).

" policy which replaced rail services with buses also failed. In many cases the replacement bus services were far slower and less convenient than the train services they were meant to replace, resulting in them being extremely unpopular with the public. Replacement bus services were often simply run between the (now disused) station sites, robbing the replacement service of any potential advantage over the closed rail service a bus service might have had. Most replacement bus services only lasted a few years before they were removed due to a lack of patronage, leaving large parts of the country with no public transport service.

and pollution

caused by increasing reliance on cars which followed, and also by the general public unrest caused by the cuts. The 1973 oil crisis

brought a final end of large scale railway closures, by highlighting the need for an energy efficient—and widespread—public transport network.

One of the last major railway closures (and possibly one of the most controversial) resulting from the Beeching Axe was of the 98-mile long (158 km) Waverley Route main line between Carlisle

, Hawick and Edinburgh

, in 1969. Plans have since been made in 2006 with the approval of the Scottish Parliament

to re-open a significant section of this line. With a few exceptions, after the early 1970s proposals to close other lines were met with vociferous public opposition and were quietly shelved. This opposition likely stemmed from the public's experience of the many line closures during the main years of the cuts in the mid and late 1960s. Today, many of Britain's railways still run at a deficit and require subsidies.

Beeching's reports made no stipulation for the handling of land after line closures. Throughout the 20th century British Rail operated a policy of disposing land which was surplus to requirement as a source of income. Many bridges, cuttings and embankments have been removed from former lines and the land sold off for development. Closed station buildings on remaining lines have often been either demolished or sold. Increasing pressure on land use in the UK throughout the 20th century meant that protection of closed trackbeds as in larger countries (such as the US Rail Bank scheme which holds former railway land for possible future use) was not practical. Many redundant structures from closed lines remain, such as bridges over other lines and drainage culverts. These often require ongoing maintenance as part of the rail infrastructure while providing no benefit. In these cases the costs have not been saved by closing lines, demonstrating an aspect of the report's short-sighted approach.

to Princes Risborough

. After the closure of the GCR

and subsequent singling works, all of the stations on the remaining line were reduced to a single platform until the line was re-doubled by Chiltern Railways in the early part of the 21st century. Again this demonstrates inconsistencies in the rail rationalisation undertaken.

Another example is the Kyle of Lochalsh Line

from Inverness

to Dingwall

. Reduced capacity on this line is now the major barrier to increasing the number of trains on the Far North Line from Inverness to Thurso

and Wick

. The West of England Main Line

(the LSWR line, not the GWR line), formerly an express route from London to the South-West, was largely reduced to a single track west of Salisbury and effectively reduced to a secondary cross-country line, since at national level it was viewed as duplicating the Great Western Main Line

. Some road schemes have been prioritised over existing rail lines requiring lines to be reduced to single tracks. The Shrewsbury to Chester Line

from Chester

to Wrexham General

line has a dual carriageway bridge on the A483 over the railway where space was only left for a single track. This constraint on the network now hampers frequency and timekeeping on the north-south Wales railway service.

Capacity problems exist on some lines, many of which now carry much greater volumes of passengers than during the time of the report. Traffic on the single track Golden Valley Line

between Kemble and Swindon

and the Cotswold Line

between Oxford and Worcester has increased significantly and a dual track line is now being reinstated here. On the Cotswold line, there are now twice as many trains trying to run on the single track than in the 1960s after singling, this route is also now being partially reinstated as a dual track. Punctuality and reliability can be harder to achieve on single lines. Delays are compounded when trains have to wait for a passing train to clear a single line section. Journey times are extended as waiting time and catch up time is added to the timetable. A journey from London to Worcester takes much longer today than before rationalisation, in spite of faster rolling stock.

, the possibility of more Beeching-style cuts was raised again, briefly. In 1983 Sir David Serpell, a civil servant who had worked with Beeching, compiled what became known as the Serpell Report

which set out a number of options. Beeching recommended closures and Serpell did not. Serpell alleged that a profitable railway (if that was the aim) could only be achieved by closing much of what remained. The infamous "Option A" in this report was illustrated by a map of a truly vestigial system with, for example, no railways west of Bristol and none in Scotland apart from the central belt. This was much more than Beeching had ever dared to suggest. Serpell was shown to have some serious weaknesses, such as the closure of the Midland Main Line

(a busy route for coal transport to power stations), and even the East Coast Main Line between Berwick-upon-Tweed

and Edinburgh, part of the key London/Edinburgh link. The report met with fierce resistance from many quarters and, having lost credibility, it was quickly abandoned.

In addition a small but significant number of closed stations have reopened, and passenger services been restored on lines where they had been removed. Many of these were in the urban metropolitan counties

where passenger transport executive

s have a role in promoting local passenger rail use.

, the Snow Hill tunnel

, south of Farringdon station

, was reopened for passenger use in 1988, providing a link between the Midland Main Line

, from St Pancras station, and the former Southern Railway

, via London Bridge station

. This line, named Thameslink

, now provides a north-south cross London rail link and it has been highly successful, providing a spine of service from to . Although its closure was not as a result of Beeching, its success demonstrates the possibilities for rail expansion, in contradiction of Beeching's approach. Since May 2010, Transport for London

has restored most of the section of line which once connected and , as part of its East London Line

project on the Overground network

.

(closed in 1967 but not mentioned by Beeching), the Oxford to Bicester Line

was reopened in 1987 by the Network SouthEast

sector of British Rail. Full re-opening of the Western section of the Varsity line looks likely to happen by 2028. The Chiltern Main Line

was redoubled in two stages between 1998 and 2002 between Princes Risborough

and Aynho Junction. Chandler's Ford

in Hampshire

opened its new railway station in 2003, on the Romsey to Eastleigh link

which had closed to passengers in 1969. Part of the London to Aylesbury Line

was extended north along the former Great Central Main Line

to a brand new station called Aylesbury Vale Parkway

which opened in December 2008.

in Nottinghamshire

, between Nottingham and Worksop

via Mansfield

, which reopened in the early 1990s. Previously Mansfield had been the largest town in Britain without a rail link.

More immediate reopenings occurred on the Lincoln to Peterborough line

. The section between Peterborough and Spalding closed to passengers on 5 October 1970 and re-opened on 7 June 1971. North of Spalding

, Ruskington Station

re-opened on 5 May 1975. Metheringham Station

followed on 6 October 1975.

a new Birmingham Snow Hill station

was opened in 1987 to replace the earlier Snow Hill station. The tunnel underneath Birmingham

city centre that served the station was also reopened, along with the line towards Kidderminster and Worcester

. This introduced a new service between Birmingham and London, terminating at Marylebone

. The former line from Snow Hill to Wolverhampton has been reopened as the Midland Metro

tram

system. The line from Coventry to Nuneaton

was reopened to passengers in 1988. Despite the successful and potential re-opening of many rail routes as light-rail and metro lines, the concept is still under-threat due to the varying popularity of these schemes with successive governments. The Walsall–Hednesford line

was reopened to passenger traffic in 1989 and extended to Rugeley

in 1997. Regular passenger services were terminated between and in 2008 on cost and efficiency grounds. Some commentators believe an intermediate station at Willenhall should have been included with the original reopening.

The South Staffordshire Line

between Stourbridge and Walsall is set to re-open in the future as a part of the Midland Metro expansion scheme. The line will be shared between trams and freight trains.

as a declining industrial region. As a result, it lost the majority of its network. Since 1983 it has experienced a major rail revival, with 32 new stations such as Llanharan

, and four lines reopened within 20 miles (32 km) of each other: Abercynon–Aberdare

, Barry–Bridgend

via , Bridgend–Maesteg

and the Ebbw Valley Railway via Newbridge.

, the section of the Glasgow Central Railway

between and was reopened in November 1979 establishing the Argyle Line

connecting the Hamilton Circle to the North Clyde Line

. The intermediate stations at , , Glasgow Central Low Level and were reopened, however those at and remained closed, although a new station was created at . The Argyle Line was further extended in December 2005 when a four-mile (6.4 km) section of the Mid Lanark Lines of the Caledonian Railway

was reopened, serving , and .

After several years of "false" starts dating to the 1980s, the railway from Stirling to Alloa

reopened on 19 May 2008, providing a passenger (and freight on to Kincardine) route once again after a 40-year gap.

on the mainline between Arbroath and Aberdeen

was shut in 1967 but 42 years later in May 2009 it was reopened. This was the 77th new or reopened station in Scotland since 1970. Others include , and all of which were closed in the mid 1960s but reinstated.

A 35-mile (56 km) stretch of the former Waverley Route between Edinburgh

and via Dalkeith is expected to be reopened in 2014 now that funding has been approved. The closure of the line in 1969 left the Scottish Borders

area without any rail links.

Several lines have also reopened as heritage railway

Several lines have also reopened as heritage railway

s.

called for a number of lines to be reopened. A total of 14 new lines, with about 40 stations are involved.

The lines involved, either wholly or in part, include:—

TV comedy series Oh, Doctor Beeching!

, which ran from 1995–1997, was set in a small fictional branch line railway station threatened with closure under the Beeching Axe.

Flanders and Swann

, writers and performers of satirical songs, wrote a lament for lines closed by the Beeching Axe entitled "Slow Train

". Michael Williams' book On the slow train takes its name from the Flanders and Swann song. It celebrates 12 of the most beautiful and historic journeys in Britain which were saved from the Beeching axe.

In the satirical magazine Private Eye

, the column on railway issues, "Signal Failures", is written under the pseudonym "Dr. B. Ching" as a reference to the report.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr

Doctor (title)

Doctor, as a title, originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb docēre . It has been used as an honored academic title for over a millennium in Europe, where it dates back to the rise of the university. This use spread...

Richard Beeching

Richard Beeching

Richard Beeching, Baron Beeching , commonly known as Doctor Beeching, was chairman of British Railways and a physicist and engineer...

. Although this report also proposed new modes of freight service and the modernisation of trunk passenger routes, it is remembered for recommending wholesale closure of what it considered little-used and unprofitable railway lines, the removal of stopping passenger trains and closure of local stations on other lines that remained open.

The report was a reaction to significant losses that had begun in the 1950s as the expansion in road transport began to attract passengers and goods from the railways; losses which continued to bedevil British Railways despite the introduction of the railway Modernisation Plan of 1955. Beeching proposed that only drastic action would save the railways from increasing losses in the future.

Successive governments were more keen on the cost-saving elements of the report rather than those requiring investment. More than 4000 miles (6,437.4 km) of railway and 3,000 stations closed in the decade following the report, a reduction of 25 per cent of route miles and 50 per cent of stations. To this day, Beeching's name is unfavourably synonymous with mass closure of railways and loss of many local services. This is particularly so in parts of the country that suffered most from cuts.

Pre-Beeching closures

Although Beeching is commonly associated with railway closures, a significant number of lines had closed before the 1960s, one of the earliest known being the closure of a section of the Newmarket and Chesterford Railway in 1851.After growing rapidly in the 19th century, the British railway system reached its height in the years immediately before the First World War. In 1913 there were 23,440 route miles (37,720 km) of railway.

After the war, the railways began to face competition from other modes of transport such as bus

Bus

A bus is a road vehicle designed to carry passengers. Buses can have a capacity as high as 300 passengers. The most common type of bus is the single-decker bus, with larger loads carried by double-decker buses and articulated buses, and smaller loads carried by midibuses and minibuses; coaches are...

es, car

Čar

Čar is a village in the municipality of Bujanovac, Serbia. According to the 2002 census, the town has a population of 296 people.-References:...

s and road haulage. Because of this, a modest number of railway lines were closed during the 1920s and 1930s. Most of these early closures were of the most marginal country branch lines such as the Charnwood Forest Railway

Charnwood Forest Railway

The Charnwood Forest Railway was a branch line in Leicestershire constructed by the Charnwood Forest Company between 1881 and 1883. The branch line ran from Coalville to the town of Loughborough....

, closed to passengers in 1931, and of short suburban lines that had fallen victim to competition from buses and tram

Tram

A tram is a passenger rail vehicle which runs on tracks along public urban streets and also sometimes on separate rights of way. It may also run between cities and/or towns , and/or partially grade separated even in the cities...

s, which offered a more frequent service. An example of this was the Harborne Line in Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, which closed to passengers in 1934.

Also, a number of lines had been built by rival companies between the same places to compete with each other. With the grouping of railway companies in 1923, many of these duplicating lines became redundant and were closed. In total 1264 miles (2,034.2 km) of railway were closed to passengers between 1923 and 1939.

With the onset of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the railways gained a reprieve as they became essential to the war effort

War effort

In politics and military planning, a war effort refers to a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and human—towards the support of a military force...

and were heavily used. By the time the railways were nationalised

Nationalization

Nationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

in 1948, they were in a substantially worn down condition, as little maintenance or investment was carried out during the war.

Early closures under British Railways

By the early 1950s, railway closures began again. The British Transport CommissionBritish Transport Commission

The British Transport Commission was created by Clement Attlee's post-war Labour government as a part of its nationalisation programme, to oversee railways, canals and road freight transport in Great Britain...

(BTC) created the "Branch Lines Committee" in 1949, with a remit to close the least used branch lines. Many of the most minor and little-used lines were closed during this period, though some secondary cross-country lines were closed as well, such as the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway

Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway

The Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway, was a joint railway owned by the Midland Railway and the Great Northern Railway in eastern England, affectionately known as the 'Muddle and Get Nowhere' to generations of passengers, enthusiasts, and other users.The main line ran from Peterborough to...

in East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

, which was closed in 1959. In total 3318 miles (5,339.8 km) of railway were closed between 1948 and 1962.

This period saw the beginnings of a closures protest movement led by the Railway Development Association, whose most famous member was the poet John Betjeman

John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman, CBE was an English poet, writer and broadcaster who described himself in Who's Who as a "poet and hack".He was a founding member of the Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture...

.

1955 modernisation

By the early 1950s, economic recovery and the end of fuel rationing meant that pre-war trends of increasing competition for the railways reasserted themselves as more people could afford cars and road haulage could compete for freight. The railways struggled to adapt. Britain's railways had fallen behind other countries. In an attempt to catch up, the BTC unveiled the Modernisation Plan in 1955, which proposed to spend more than £1,240 million on modernising the railways (£ as of ), replacing steamSteam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

with diesel

Diesel locomotive

A diesel locomotive is a type of railroad locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engine, a reciprocating engine operating on the Diesel cycle as invented by Dr. Rudolf Diesel...

and electric locomotive

Electric locomotive

An electric locomotive is a locomotive powered by electricity from overhead lines, a third rail or an on-board energy storage device...

s. The plan promised to win back traffic and restore the railways to profit by 1962. Much of the Modernisation Plan was approved.

Traffic on the railways remained fairly steady during the 1950s, but the economics of the railway network steadily deteriorated. This was largely due to costs such as labour rising faster than income. Fares and freight charges were repeatedly frozen by the government in an attempt to control inflation

Inflation

In economics, inflation is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation also reflects an erosion in the purchasing power of money – a...

and please the electorate.

The result was that by 1955 income no longer covered operating costs, and the situation steadily worsened. Much of the money spent on the Modernisation Plan had been borrowed. By the early 1960s the railways were in financial crisis. Operating losses increased to £68m in 1960, £87m in 1961, and £104m in 1962 (£ as of ). The BTC could no longer pay interest on borrowed money, which worsened the financial problem. The government lost patience and looked for radical solutions.

In tune with the mood of the early 1960s, the transport minister in Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

's Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

government was Ernest Marples

Ernest Marples

Alfred Ernest Marples, Baron Marples PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Postmaster General and Minister of Transport. After his retirement from active politics in 1974 Marples was elevated to the peerage...

, director of a road-construction company (his two-thirds shareholding was divested to his wife while he was a minister to avoid potential conflict of interests). Marples believed the future of transport lay with roads and that railways were a relic of the Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

past.

An advisory group, known as the Stedeford Committee after its chairman, Sir Ivan Stedeford

Ivan Stedeford

Sir Ivan Arthur Rice Stedeford, GBE was a British industrialist and philanthropist.Stedeford was Chairman and Managing Director of Tube Investments and one of Britain's leading 20th-century industrialists....

, was set up to report on the state of British transport and to provide recommendations. Also on the committee was Richard Beeching, at the time technical director of ICI

Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries was a British chemical company, taken over by AkzoNobel, a Dutch conglomerate, one of the largest chemical producers in the world. In its heyday, ICI was the largest manufacturing company in the British Empire, and commonly regarded as a "bellwether of the British...

. He was later, in 1961, appointed chairman of the new British Railways Board. Stedeford and Beeching clashed on matters related to the latter's proposals to prune the rail infrastructure. In spite of questions in Parliament, Sir Ivan's report was published only much later, and the proposals for the future of the railways that came to be known as the Beeching Plan were adopted by the government, resulting in the closure of a third of the rail network and the scrapping of a third of a million freight wagons.

Beeching believed railways should be a business and not a public service, and that if parts of the railway system did not pay their way—like some rural branch lines—they should close. His reasoning was that once unprofitable lines were closed, the remaining system would be restored to profitability.

Beeching I

This study took place during the week ending 23 April 1962, two weeks after Easter, and concluded that 30 per cent of miles carried just 1 per cent of passengers and freight, and half of all stations contributed just 2 per cent of income.

The report The Reshaping of British Railways (or Beeching I report) of 27 March 1963 proposed that of Britain's 18000 miles (28,968.1 km) of railway, 6000 miles (9,656 km) of mostly rural branch and cross-country lines should close. Further, many other rail lines should be kept open for freight only, and many lesser-used stations should close on lines that were to be kept open. The report was accepted by the Government.

At the time, the controversial report was called the Beeching Bombshell or the Beeching Axe by the press. It sparked an outcry from communities that would lose their rail services, many of which (especially in the case of rural communities) had no other public transport.

The government argued that many services could be provided more cheaply by bus

Bus

A bus is a road vehicle designed to carry passengers. Buses can have a capacity as high as 300 passengers. The most common type of bus is the single-decker bus, with larger loads carried by double-decker buses and articulated buses, and smaller loads carried by midibuses and minibuses; coaches are...

es, and promised that abandoned rail services would have their places taken by bus services.

A significant part of the report proposed that British Rail electrify

Railway electrification in Great Britain

Railway electrification in Great Britain started towards of the 19th century. A great range of voltages have been used in the intervening period using both overhead lines and third rails, however the most common standard for mainline services is now 25 kV AC using overhead lines and the...

some major main lines and adopt containerised freight traffic instead of outdated and uneconomic wagon-load traffic. Some of those plans were eventually adopted, such as the creation of the Freightliner

Freightliner (UK)

Freightliner Group Limited is a rail freight and logistics company, founded in 1995 and now operating in the United Kingdom, Poland, and Australia. It is the second largest rail freight operator in the UK, after DB Schenker Rail .- History :...

concept and further electrification of the West Coast Main Line

West Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line is the busiest mixed-traffic railway route in Britain, being the country's most important rail backbone in terms of population served. Fast, long-distance inter-city passenger services are provided between London, the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and the...

from Crewe

Crewe railway station

Crewe railway station was completed in 1837 and is one of the most historic railway stations in the world. Built in fields near to Crewe Hall, it originally served the village of Crewe with a population of just 70 residents...

to Glasgow

Glasgow Central station

Glasgow Central is the larger of the two present main-line railway terminals in Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland. The station was opened by the Caledonian Railway on 31 July 1879 and is currently managed by Network Rail...

in 1974. Additionally the staff terms and conditions were improved over time.

Rail closures by year

At its peak in 1950, British Railway's system was around 21000 miles (33,796.1 km) and 6,000 stations. By 1975, the system had shrunk to 12000 miles (19,312.1 km) of track and 2,000 stations; it has remained roughly this size thereafter.

Closures of unremunerative lines had been ongoing throughout the 20th century. Numbers increased in the 1950s, as the Branchline Committee of BR

BR

- Places :* Bedroom* BR postcode area, a group of eight postal districts in southeast London* Baton Rouge, Louisiana* Brazil , according to:** Its two-letter country code defined in ISO 3166-1 alpha-2** The prefix for Brazil's ISO 3166-2 subdivision codes...

also looked for uncontentious duplicated lines as candidates for closure. Approximately 3000 miles (4,828 km) of line had already been closed between nationalisation and the publication of Beeching's report. After publication, the closure process was accelerated markedly.

The list below shows 7000 miles of closures, compared to the 9,000 miles stated above, which may be partly explained by freight-only line closures.

| Year | Total length closed |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 150 miles (241.4 km) |

| 1951 | 275 miles (442.6 km) |

| 1952 | 300 miles (482.8 km) |

| 1953 | 275 miles (442.6 km) |

| 1954 to 1957 | 500 miles (804.7 km) |

| 1958 | 150 miles (241.4 km) |

| 1959 | 350 miles (563.3 km) |

| 1960 | 175 miles (281.6 km) |

| 1961 | 150 miles (241.4 km) |

| 1962 | 780 miles (1,255.3 km) |

| Beeching report published | |

| 1963 | 324 miles (521.4 km) |

| 1964 | 1058 miles (1,702.7 km) |

| 1965 | 600 miles (965.6 km) |

| 1966 | 750 miles (1,207 km) |

| 1967 | 300 miles (482.8 km) |

| 1968 | 400 miles (643.7 km) |

| 1969 | 250 miles (402.3 km) |

| 1970 | 275 miles (442.6 km) |

| 1971 | 23 miles (37 km) |

| 1972 | 50 miles (80.5 km) |

| 1973 | 35 miles (56.3 km) |

| 1974 | 0 mile (0 km) |

Recommendations not implemented

Not all the recommended closures were implemented; a number of lines were kept open for political reasons. For example, lines through the Scottish HighlandsScottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

such as the Far North Line

Far North Line

The Far North Line is a rural railway line entirely within the Highland area of Scotland, extending from Inverness to Thurso and Wick.- Route :...

and the West Highland Line

West Highland Line

The West Highland Line is considered the most scenic railway line in Britain, linking the ports of Mallaig and Oban on the west coast of Scotland to Glasgow. The line was voted the top rail journey in the world by readers of independent travel magazine Wanderlust in 2009, ahead of the iconic...

, although listed for closure, were kept open, in part because of pressure from the powerful Highland lobby. The Central Wales Line

Heart of Wales Line

The Heart of Wales Line is a railway line running from Craven Arms in Shropshire to Llanelli in South Wales. It runs, as the name suggests, through some of the heartlands of Wales. It serves a number of rural centres en route, including several once fashionable spa towns, including Llandrindod Wells...

was said to have been kept open because it passed through so many marginal constituencies that no one dared to close it.

In addition, lines such as the Tamar Valley Line

Tamar Valley Line

The Tamar Valley Line is a railway line from Devonport in Plymouth Devon, to Gunnislake in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The line follows the River Tamar for much of its route.-History:...

in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

and Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

were kept open because the local roads were poor.

Some lines not recommended for closure were eventually closed, such as the Woodhead Line

Woodhead Line

The Woodhead Line was a railway line linking Sheffield, Penistone and Manchester in the north of England. A key feature of the route is the passage under the high moorlands of the northern Peak District through the Woodhead Tunnels...

between Manchester and Sheffield in 1981, after the freight traffic (most notably coal) on which it had relied, declined.

Beeching II

This report identified lines which were believed to justify large-scale investment to meet the likely demand over the next 20 years. Some railway supporters assumed that any other line would be closed sooner or later, although the report itself was careful to explain that no decision had been taken about them. ("The purpose of this study is to select routes for future intensive use, not to select lines for closure...")

As the map shows, a small proportion of railway lines were highlighted. In Scotland only the Central Belt

Central Belt

The Central Belt of Scotland is a common term used to describe the area of highest population density within Scotland. Despite the name, it is not geographically central but is nevertheless situated at the 'waist' of Scotland on a conventional map and the term 'central' is used in many local...

routes and the lines via Fife and Perth to Aberdeen were selected for development, and none in Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

at all, apart from the Great Western Main Line as far as Swansea. Many towns in south east England were not on selected lines, including places like Hastings and Eastbourne, although as the report also said that commuter routes would need "special consideration", major closures in the south east were probably the most unlikely of all.

Beeching II: Major lines not selected for development

- East Coast Main LineEast Coast Main LineThe East Coast Main Line is a long electrified high-speed railway link between London, Peterborough, Doncaster, Wakefield, Leeds, York, Darlington, Newcastle and Edinburgh...

between Newcastle upon TyneNewcastle upon TyneNewcastle upon Tyne is a city and metropolitan borough of Tyne and Wear, in North East England. Historically a part of Northumberland, it is situated on the north bank of the River Tyne...

and EdinburghEdinburghEdinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area... - Midland Main LineMidland Main LineThe Midland Main Line is a major railway route in the United Kingdom, part of the British railway system.The present-day line links London St...

between LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

and LeicesterLeicesterLeicester is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England, and the county town of Leicestershire. The city lies on the River Soar and at the edge of the National Forest...

including St Pancras StationSt Pancras railway stationSt Pancras railway station, also known as London St Pancras and since 2007 as St Pancras International, is a central London railway terminus celebrated for its Victorian architecture. The Grade I listed building stands on Euston Road in St Pancras, London Borough of Camden, between the... - North Wales Coast LineNorth Wales Coast LineThe North Wales Coast Line is the railway line from Crewe to Holyhead. Virgin Trains consider their services along it to be a spur of the West Coast Main Line. The first section from Crewe to Chester was built by the Chester and Crewe Railway and absorbed by the Grand Junction Railway shortly...

between ChesterChesterChester is a city in Cheshire, England. Lying on the River Dee, close to the border with Wales, it is home to 77,040 inhabitants, and is the largest and most populous settlement of the wider unitary authority area of Cheshire West and Chester, which had a population of 328,100 according to the...

and HolyheadHolyheadHolyhead is the largest town in the county of Anglesey in the North Wales. It is also a major port adjacent to the Irish Sea serving Ireland.... - All other Welsh lines apart from the Great Western Main LineGreat Western Main LineThe Great Western Main Line is a main line railway in Great Britain that runs westwards from London Paddington station to the west of England and South Wales. The core Great Western Main Line runs from London Paddington to Temple Meads railway station in Bristol. A major branch of the Great...

to NewportNewportNewport is a city and unitary authority area in Wales. Standing on the banks of the River Usk, it is located about east of Cardiff and is the largest urban area within the historic county boundaries of Monmouthshire and the preserved county of Gwent...

, CardiffCardiffCardiff is the capital, largest city and most populous county of Wales and the 10th largest city in the United Kingdom. The city is Wales' chief commercial centre, the base for most national cultural and sporting institutions, the Welsh national media, and the seat of the National Assembly for...

and SwanseaSwanseaSwansea is a coastal city and county in Wales. Swansea is in the historic county boundaries of Glamorgan. Situated on the sandy South West Wales coast, the county area includes the Gower Peninsula and the Lliw uplands... - Settle and Carlisle Railway

- Cumbrian Coast LineCumbrian Coast LineThe Cumbrian Coast Line is a rail route in North West England, running from Carlisle to Barrow-in-Furness via Workington and Whitehaven. The line forms part of Network Rail route NW 4033, which continues via Ulverston and Grange-over-Sands to Carnforth, where it connects with the West Coast Main...

- Great Western secondary main lineReading to Taunton lineThe Reading to Taunton line also known as the Berks and Hants is a major branch of the Great Western Main Line that diverges at Reading, running to Cogload Junction near Taunton, where it joins the Bristol to Exeter line....

between ReadingReading, BerkshireReading is a large town and unitary authority area in England. It is located in the Thames Valley at the confluence of the River Thames and River Kennet, and on both the Great Western Main Line railway and the M4 motorway, some west of London....

and TauntonTauntonTaunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset.... - West of England Main LineWest of England Main LineThe West of England Main Line is a British railway line that runs from , Hampshire to Exeter St Davids in Devon, England. Passenger services run between London Waterloo station and Exeter...

between BasingstokeBasingstokeBasingstoke is a town in northeast Hampshire, in south central England. It lies across a valley at the source of the River Loddon. It is southwest of London, northeast of Southampton, southwest of Reading and northeast of the county town, Winchester. In 2008 it had an estimated population of...

and ExeterExeterExeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the... - Cornish Main LineCornish Main LineThe Cornish Main Line is a railway line in the United Kingdom, which forms the backbone for rail services in Cornwall, as well as providing a direct line to London.- History :...

west of PlymouthPlymouth railway stationPlymouth railway station serves the city of Plymouth, Devon, England. It is situated on the northern edge of the city centre close to the North Cross roundabout... - All lines in south east England apart from the main lines out of London to SouthamptonSouthamptonSouthampton is the largest city in the county of Hampshire on the south coast of England, and is situated south-west of London and north-west of Portsmouth. Southampton is a major port and the closest city to the New Forest...

, BournemouthBournemouthBournemouth is a large coastal resort town in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. According to the 2001 Census the town has a population of 163,444, making it the largest settlement in Dorset. It is also the largest settlement between Southampton and Plymouth...

, PortsmouthPortsmouthPortsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

, BrightonBrightonBrighton is the major part of the city of Brighton and Hove in East Sussex, England on the south coast of Great Britain...

and DoverDoverDover is a town and major ferry port in the home county of Kent, in South East England. It faces France across the narrowest part of the English Channel, and lies south-east of Canterbury; east of Kent's administrative capital Maidstone; and north-east along the coastline from Dungeness and Hastings... - All lines serving East Anglia with the exception of the Great Eastern Main LineGreat Eastern Main LineThe Great Eastern Main Line is a 212 Kilometre major railway line of the British railway system, which connects Liverpool Street in the City of London with destinations in east London and the East of England, including Chelmsford, Colchester, Ipswich, Norwich and several coastal resorts such as...

- All Scottish lines north of GlasgowGlasgowGlasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

, PerthPerth, ScotlandPerth is a town and former city and royal burgh in central Scotland. Located on the banks of the River Tay, it is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and the historic county town of Perthshire...

, DundeeDundeeDundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

and AberdeenAberdeenAberdeen is Scotland's third most populous city, one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas and the United Kingdom's 25th most populous city, with an official population estimate of ....

and west of the West Coast Main LineWest Coast Main LineThe West Coast Main Line is the busiest mixed-traffic railway route in Britain, being the country's most important rail backbone in terms of population served. Fast, long-distance inter-city passenger services are provided between London, the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and the...

In the event, this report does not seem to have made any lasting impression on the recently-elected Labour government, in power since October 1964, and Beeching resigned from BR two months after it was published.

Major railway closures may have been considered afresh since Beeching's time, but apart from the brief ripple caused by the Serpell Report

Serpell Report

The Serpell Report was produced by a committee chaired by Sir David Serpell, a senior civil servant. It was commissioned by the government of Margaret Thatcher to examine the state and long-term prospects of Great Britain's railway system. There were two main parts to the report. The first part...

in 1982, they have not been formally proposed again.

Changing attitudes and policies

In 1964 a Labour government was elected under Prime MinisterPrime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

. During the election campaign, Labour promised to halt the rail closures if elected. Once elected, they quickly backtracked on this promise, and the closures continued, at a faster rate than under the previous administration and until the end of the decade.

In 1965, Barbara Castle

Barbara Castle

Barbara Anne Castle, Baroness Castle of Blackburn , PC, GCOT was a British Labour Party politician....

was appointed transport minister and she decided that at least 11,000 route miles (17,700 km) would be needed for the foreseeable future and that the railway system should be stabilised at around this size.

Towards the end of the 1960s it became increasingly clear that rail closures were not producing the promised savings or bringing the rail system out of deficit and were unlikely ever to do so. Castle also stipulated that some rail services that could not pay their way but had a valuable social role should be subsidised. By the time the legislation allowing this was introduced into the 1968 Transport Act, (Section 39 of this Act made provision for a subsidy to be paid by the Treasury for a three-year period) many of the services and railway lines that would have qualified and benefited from these subsidies had already been closed or removed, thus lessening the impact of the legislation. Nevertheless, a number of branch lines were saved by this legislation.

Aftermath

The closures failed in their main purpose of trying to restore the railways to profitability, with the promised savings failing to materialise. By closing almost a third of the rail network, Beeching managed to achieve a saving of just £30 million, whilst overall losses were running in excess of £100 million. The shortfall arose mainly because the branch lines acted as feeders to the main lines and that feeder traffic was lost when the branches closed. This in turn meant less traffic and less income for the increasingly vulnerable main lines.The assumption at the time was that car

Automobile

An automobile, autocar, motor car or car is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transporting passengers, which also carries its own engine or motor...

owners would drive to the nearest railhead (which was usually the junction where the closed branch line would otherwise have taken them) and continue their journey onwards by train. In practice having left home in their cars people used them for the whole journey. The same problem occurred with the movement of goods and freight: without branch lines, the railways' ability to transport goods "door to door" was dramatically reduced. Like the passenger model, it was assumed that lorries would pick up goods, transport them to the nearest railhead, where they would be taken across the country by train, unloaded onto another lorry and taken to their destination. The development of the motorway network, the advent of containerisation, improvements in road haulage vehicles, and the economic costs of having two break-of-bulk points all combined to make long-distance road transport a more viable alternative.

Another reason for Beeching plan's not achieving any great savings was that many of the closed lines ran at only a small deficit. Some lines such as the Sunderland

Sunderland station

Sunderland Station is a National Rail and Tyne and Wear Metro station in the city centre of Sunderland, North East England. It is the only station in the country where both heavy rail and light rail services use the same platforms...

to West Hartlepool line cost only £291 per mile to operate. Closures of such small-scale loss making lines made little difference to the overall deficit. Perhaps ironically the busiest commuter routes had always lost the greatest amount of money, but even Beeching realised it would be impractical to close them.

The Beeching reports recommended against attempts to make loss-making lines profitable. Changes to light railway

Light railway

Light railway refers to a railway built at lower costs and to lower standards than typical "heavy rail". This usually means the railway uses lighter weight track, and is more steeply graded and tightly curved to avoid civil engineering costs...

services (already in use on some branch lines at the time of the report) were attacked by Beeching, who wrote: "The third suggestion, that rail buses should be substituted for trains, ignores the high cost of providing the route itself, and also ignores the fact that rail buses are more expensive vehicles than road buses." There is little in the Beeching report recommending general economies (in administration costs, working practices and so on). For example, a number of the stations that were closed were fully staffed eighteen hours a day, on lines controlled by multiple Victorian era

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

signalboxes (again fully staffed, often throughout the day). Reductions in operating costs could have been made by reducing staff and removing redundant services on these lines whilst still enabling these stations to stay open. Such concepts have since been successfully utilised by British Rail and its successors on lesser-used lines that survived the axe (such as the East Suffolk Line

East Suffolk Line

The East Suffolk Line is an un-electrified secondary railway line running between Ipswich and Lowestoft in Suffolk, England. The traffic along the route consists of passenger services operated by National Express East Anglia, while nuclear flask trains for the Sizewell nuclear power stations are...

from Ipswich to Lowestoft which survives as a "basic railway"). Such recommendations were absent from the Beeching reports.

In retrospect, many of the specific Beeching closures can be seen as very short-sighted. Many of the closed routes would now be heavily used, possibly even important trunk routes. The Settle-Carlisle Railway

Settle-Carlisle Railway

The Settle–Carlisle Line is a long main railway line in northern England. It is also known as the Settle and Carlisle. It is a part of the National Rail network and was constructed in the 1870s...

was threatened with closure, reprieved and now handles more traffic (both passenger and freight) than at any time in its history. The Great Central Main Line

Great Central Main Line

The Great Central Main Line , also known as the London Extension of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway , is a former railway line which opened in 1899 linking Sheffield with Marylebone Station in London via Nottingham and Leicester.The GCML was the last main line railway built in...

, the last trunk route built in Britain until the opening of High Speed 1 in 2007, was intended to provide a link to the north of England with a proposed Channel Tunnel

Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel is a undersea rail tunnel linking Folkestone, Kent in the United Kingdom with Coquelles, Pas-de-Calais near Calais in northern France beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. At its lowest point, it is deep...

. It was built to the wider Continental loading gauge

Loading gauge

A loading gauge defines the maximum height and width for railway vehicles and their loads to ensure safe passage through bridges, tunnels and other structures...

and constructed to the same standards as a modern high speed line, with no level crossings and curves and gradients kept to an absolute minimum. This line closed in stages between 1966 and 1969 after just 60 years of service, 28 years before the eventual opening of the Channel Tunnel

Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel is a undersea rail tunnel linking Folkestone, Kent in the United Kingdom with Coquelles, Pas-de-Calais near Calais in northern France beneath the English Channel at the Strait of Dover. At its lowest point, it is deep...

rail link. Since the opening of the Channel Tunnel and High Speed 1, there has been discussion about "High Speed 2

High Speed 2

High Speed 2 is a proposed high-speed railway between London and the Midlands, the North of England, and potentially at a later stage the central belt of Scotland. The project is being developed by High Speed Two Ltd, a company established by the British government...

" linking the tunnel to the North of England and Scotland. While this route would have been served by a simple extension of the closed line's original function, it would now be very difficult and expensive to construct as much of the former GCML route has been levelled or built on (see below).

Failures of bus-substitution

The "bustitutionBustitution

The word bustitution is a neologism sometimes used to describe the practice of replacing a passenger train service with a bus service either on a temporary or permanent basis. The word is a portmanteau of the words "bus" and "substitution"...

" policy which replaced rail services with buses also failed. In many cases the replacement bus services were far slower and less convenient than the train services they were meant to replace, resulting in them being extremely unpopular with the public. Replacement bus services were often simply run between the (now disused) station sites, robbing the replacement service of any potential advantage over the closed rail service a bus service might have had. Most replacement bus services only lasted a few years before they were removed due to a lack of patronage, leaving large parts of the country with no public transport service.

Final closures under Beeching

The closures were brought to a halt in the early 1970s when it became apparent that they were not useful. The small amount of money saved by closing railways was outweighed by the congestionTraffic congestion

Traffic congestion is a condition on road networks that occurs as use increases, and is characterized by slower speeds, longer trip times, and increased vehicular queueing. The most common example is the physical use of roads by vehicles. When traffic demand is great enough that the interaction...

and pollution

Pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into a natural environment that causes instability, disorder, harm or discomfort to the ecosystem i.e. physical systems or living organisms. Pollution can take the form of chemical substances or energy, such as noise, heat or light...

caused by increasing reliance on cars which followed, and also by the general public unrest caused by the cuts. The 1973 oil crisis

1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis started in October 1973, when the members of Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries or the OAPEC proclaimed an oil embargo. This was "in response to the U.S. decision to re-supply the Israeli military" during the Yom Kippur war. It lasted until March 1974. With the...

brought a final end of large scale railway closures, by highlighting the need for an energy efficient—and widespread—public transport network.

One of the last major railway closures (and possibly one of the most controversial) resulting from the Beeching Axe was of the 98-mile long (158 km) Waverley Route main line between Carlisle

Carlisle railway station

Carlisle railway station, also known as Carlisle Citadel station, is a railway station whichserves the Cumbrian City of Carlisle, England, and is a major station on the West Coast Main Line, lying south of Glasgow Central, and north of London Euston...

, Hawick and Edinburgh

Edinburgh Waverley railway station

Edinburgh Waverley railway station is the main railway station in the Scottish capital Edinburgh. Covering an area of over 25 acres in the centre of the city, it is the second-largest main line railway station in the United Kingdom in terms of area, the largest being...

, in 1969. Plans have since been made in 2006 with the approval of the Scottish Parliament

Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament is the devolved national, unicameral legislature of Scotland, located in the Holyrood area of the capital, Edinburgh. The Parliament, informally referred to as "Holyrood", is a democratically elected body comprising 129 members known as Members of the Scottish Parliament...

to re-open a significant section of this line. With a few exceptions, after the early 1970s proposals to close other lines were met with vociferous public opposition and were quietly shelved. This opposition likely stemmed from the public's experience of the many line closures during the main years of the cuts in the mid and late 1960s. Today, many of Britain's railways still run at a deficit and require subsidies.

Disposals of land and structures

Many of the areas along lines closed by the Beeching Axe have expanded and grown over the last 40 years. Where some lines were not profitable in 1963 (on a backdrop of falling passenger numbers and a rise in car use on uncongested roads) it seems likely that they could be profitable now. Many could certainly have a desirable impact on reducing road congestion and pollution, as well as relieving congestion on the railway lines that have remained open. In many instances it would be prohibitively expensive for these axed routes to be reopened.Beeching's reports made no stipulation for the handling of land after line closures. Throughout the 20th century British Rail operated a policy of disposing land which was surplus to requirement as a source of income. Many bridges, cuttings and embankments have been removed from former lines and the land sold off for development. Closed station buildings on remaining lines have often been either demolished or sold. Increasing pressure on land use in the UK throughout the 20th century meant that protection of closed trackbeds as in larger countries (such as the US Rail Bank scheme which holds former railway land for possible future use) was not practical. Many redundant structures from closed lines remain, such as bridges over other lines and drainage culverts. These often require ongoing maintenance as part of the rail infrastructure while providing no benefit. In these cases the costs have not been saved by closing lines, demonstrating an aspect of the report's short-sighted approach.

Track rationalisation

One effect of the Beeching closures was the reduction of some formerly double track sections of line to single tracks, an example being the section of line from BicesterBicester North railway station

Bicester North is a station on the Chiltern Main Line, one of two stations serving Bicester. Services operated by Chiltern Railways run south to and north to , and .Bicester North is the larger of Bicester's two stations...

to Princes Risborough

Princes Risborough railway station

Princes Risborough station is a railway station on the Chiltern Main Line that serves the town of Princes Risborough in Buckinghamshire, England...

. After the closure of the GCR

Great Central Railway

The Great Central Railway was a railway company in England which came into being when the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway changed its name in 1897 in anticipation of the opening in 1899 of its London Extension . On 1 January 1923, it was grouped into the London and North Eastern...

and subsequent singling works, all of the stations on the remaining line were reduced to a single platform until the line was re-doubled by Chiltern Railways in the early part of the 21st century. Again this demonstrates inconsistencies in the rail rationalisation undertaken.

Another example is the Kyle of Lochalsh Line

Kyle of Lochalsh Line