Richard Beeching

Encyclopedia

Richard Beeching, Baron Beeching (21 April 1913 – 23 March 1985), commonly known as Doctor Beeching, was chairman of British Railways and a physicist

and engineer

. He became infamous in Britain in the early 1960s for his report "The Reshaping of British Railways", commonly referred to as the Beeching Report, which led to far-reaching changes in the railway network, popularly known as the Beeching Axe

. As a result of the report, just over 4,000 route miles were cut on cost and efficiency grounds, leaving Britain with 13721 miles (22,081.8 km) of railway lines in 1966. A further 2000 miles (3,218.7 km) were to be lost by the end of the 1960s.

on the Isle of Sheppey

in Kent

, the second of four brothers. His father was a reporter with the Kent Messenger

, his mother a schoolteacher and his maternal grandfather a dockyard worker. Shortly after his birth, Beeching's family moved to Maidstone

where his brothers Kenneth (who was killed in the Second World War) and John were born. All four Beeching boys attended the local Church of England

primary school, Maidstone All Saints, and won scholarships to Maidstone Grammar School

, where Richard was a prefect. Beeching and his elder brother Geoffrey attended Imperial College of Science & Technology

in London where both read physics

and took First Class honours degrees. His younger brothers both attended Downing College, Cambridge

.

Beeching remained at Imperial College where he undertook a research Ph.D under the supervision of Sir George Thomson

. He continued in research until 1943, first at the Fuel Research Station in Greenwich

in 1936 and then, the following year, with the Mond Nickel Laboratories

in London where he was appointed senior physicist carrying out research in the fields of physics, metallurgy

and mechanical engineering

.

In 1938 he married Ella Margaret Tiley whom he had known since his schooldays. They remained married for the rest of his life. They had no children and initially set up home in Solihull

. During the Second World War Beeching, at the age of 29, was loaned by Mond Nickel on the recommendation of a Dr. Sykes at Firth Brown Steels

to the Ministry of Supply

, where he worked in their Armament Design and Research Departments at Fort Halstead

. His first post was with the Shell Design Section where he had a rank equivalent to that of army captain. Whilst with Armament Design, Beeching worked under the Department's Superintendent and Chief Engineer, Sir Frank Smith

, a former Chief Engineer with Imperial Chemical Industries

(ICI).

After the war Smith returned to ICI as Technical Director and was replaced as Chief Engineer of Armament Design by Sir Steuart Mitchell who promoted Beeching, then 33 years old, to the post of Deputy Chief Engineer with a rank equivalent to that of Brigadier

. Beeching continued his work with armaments, particularly anti-aircraft

weaponry and small arms

. In 1948 he joined ICI as Personal Technical Assistant to Sir Frank Smith where he remained for around 18 months, working on the production lines for various products such as zip fasteners, paints and leather

cloth with a view to improving efficiency and reducing production costs. He was then appointed to the Terylene Council, and subsequently to the board of ICI Fibres Division. In 1953 he went to Canada as vice-president of ICI (Canada) Ltd and given overall responsibility for a terylene plant in Ontario

. He returned after two years to become chairman of ICI Metals Division on the recommendation of Sir Frank Smith. In 1957 he was appointed to the ICI board as Technical Director, and for a short time also served as Development Director.

Minister of Transport

, Ernest Marples

, to become a member of an advisory group on the financial state of the British Transport Commission

to be chaired by Sir Ivan Stedeford

. Smith declined but recommended Beeching in his place, a suggestion which Marples accepted. Stedeford and Beeching clashed on a number of issues connected with Beeching's proposal to drastically prune Britain's rail infrastructure. In spite of questions being asked in Parliament

, Sir Ivan's report was not published until much later.

announced in the House of Commons that Beeching would be the first Chairman of the British Railways Board

as from 1 June. The Board was the successor to the British Transport Commission

which was broken up by the Transport Act 1962

. Beeching would receive the same yearly salary that he was earning at I.C.I., the controversial sum of £24,000 (£367,000 in today's money), £10,000 more than Sir Brian Robertson

, the last chairman of the British Transport Commission, £14,000 more than Prime Minister

Harold Macmillan

and two-and-a-half times higher than the salary of any head of a nationalised industry at the time. Beeching was given a leave of absence for five years by ICI in order to carry out this task.

At that time the Government was seeking outside talent and fresh blood to sort out the huge problems of the railway network.

There was widespread concern at the time that, despite substantial investment in the 1955 Modernisation Plan, the railways continued to haemorrhage losses - from £15.6m in 1956 to £42m in 1960. Passenger and goods traffic was also declining in the face of increased competition from the roads; by 1960, one in nine families owned a car. It would be Beeching's task to find a way to returning the industry to profitability as soon as possible.

Unsurprisingly, Beeching's plans were hugely controversial not only with trade unions, but with the Labour

opposition and railway-using public. Beeching was undeterred and argued that too many lines were running at a loss, and that his charge to shape a profitable railway made cuts a logical starting point. As one author puts it, Beeching "was expected to produce quick solutions to problems that were deep-seated and not susceptible to purely intellectual analysis." For his part, Beeching was unrepentant about his role in the closures: "I suppose I'll always be looked upon as the axe man, but it was surgery, not mad chopping."

Beeching was nevertheless instrumental in modernising many aspects of the railway network, particularly a greater emphasis on block trains which did not require expensive and time-consuming shunting en route.

On 23 December 1964, Tom Fraser

informed the House of Commons that Beeching was to return to ICI in June 1965.

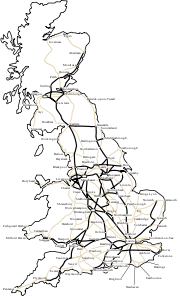

, Manchester

, Liverpool

and Scotland

would be routed through the West Coast Main Line

running to Carlisle

and Glasgow

; traffic to the north-east would be concentrated through the East Coast Main Line

which was to be closed north of Newcastle; and traffic to Wales

and the West Country

would go on the Great Western Main Line

, then to Swansea

and Plymouth

. Underpinning Beeching's proposals was his belief that there was still too much duplication in the railway network. Of the 7500 miles (12,070.1 km) of trunk route, 3700 miles (5,954.6 km) involves a choice between two routes, 700 miles (1,126.5 km) a choice of three, and over a further 700 miles (1,126.5 km) a choice of four.

These proposals were rejected by the government which put an early end to his secondment from ICI to which he returned in June 1965. It is a matter of debate whether Beeching left by mutual arrangement with the government or if he was sacked. Frank Cousins

, the Labour Minister of Technology

, revealed to the House of Commons in November 1965 that Beeching had been dismissed by Tom Fraser

. Beeching denied this, pointing out that he had returned early to ICI as he would not have had enough time to undertake an in-depth transport study before the formal end of his secondment from ICI.

he was made a life peer

as Baron Beeching, of East Grinstead

in the county of Sussex

, and in the same year he became a director of Lloyds Bank

. In 1966 he was appointed as chairman of the Royal Commission

to examine assizes and quarter sessions, and eventually proposed a mass reorganisation of the court system involving the setting-up of regional courts in cities such as Cardiff

, Birmingham

and Leeds

. The following year he became chairman of Associated Electrical Industries

, a role he also held with Redland

from 1970–77 and Furness Withy

from 1973-75.

The Beatles

considered Lord Beeching when they were trying to find someone who could sort out the business affairs of their company Apple Corps

.

: I Tried to Run a Railway (1967) ISBN 0-7110-0447-1. Neither book is in print at the time of writing (2006). Both are broadly sympathetic to Beeching's basic analysis and the proposed solution. On the other hand, Hardy points out Beeching's political naivete (see below) in moving from private to public industry. Similarly Fiennes notes that because a passenger service was producing a loss did not mean that it must always do so in future. It can reasonably be argued that too many routes were run in a traditional fashion unchanged from Edwardian Britain, whereas radical changes in operating procedures would have greatly reduced the losses generated. Beeching allegedly made no attempt to quantify what such savings could have yielded, nor which lines could have survived had practices been changed.

The political aspects of the Beeching Report remain controversial. The report was commissioned by a Conservative government with strong ties to the road construction lobby. However, the report's findings were enthusiastically endorsed and implemented by the subsequent Labour administrations which were heavily dependent for funds from unions associated with road industry associations. The general reduction of Britain's railway mileage was probably inevitable but the speed with which the two Labour governments of 1964 and 1966 pursued the report's recommendations was not. Beeching seemingly failed to realise that history would portray him as the 'axeman', even though the Secretary of State for Transport

is the only person who can authorise abandonment of railway passenger services in the UK.

Several ex-railway sites have been named after Beeching. There is a pub called Lord Beechings at the end of the Cambrian Railway at Aberystwyth

, which until its refurbishment by SA Brain & Company Ltd was decorated with various railway memorabilia, in particular regarding the Aberystwyth

- London and Aberystwyth

- Carmarthen

service, which he axed. It was previously called The Railway. The road Beechings Way at Alford, Lincolnshire

, is so named to commemorate the loss of the formerly adjacent station and line (formerly from Grimsby

to London, via Louth

and Peterborough

) under the Beeching Axe

. The road 'Beeching Drive' in Lowestoft

, Suffolk

, located on the site of the former Lowestoft North station is also so named. Coincidentally, a smaller pedestrian area in the vicinity is known as 'Stevenson's Walk'. There is a cul-de-sac in the Leicestershire

village of Countesthorpe

[about seven miles (11 km) south of Leicester

city centre] aptly named Beeching's Close. The village was served by a line between Leicester and Rugby

, closed under the Beeching Axe

. The gardens of the houses on the west side of the close meet with the boundary of the old line. East Grinstead, where Beeching lived, was formerly served by a railway line from Tunbridge Wells (West) to Three Bridges, a line most of which was closed under the Beeching Axe

. To the east of the current East Grinstead station, the line passed through a deep cutting. This cutting currently forms part of the A22 relief road through East Grinstead. Due to the depth of the cutting, locals wanted to call the road "Beeching Cut", but as this was deemed politically incorrect, it was instead called 'Beeching Way' .

, a television sitcom by David Croft and Richard Spendlove

from 1995 to 1997.

A popular Flanagan

and Allen

song became the theme song which ran:

Note: This is based on the once-well-known and railway-related poem.

Flanders and Swann

commemorated the loss of the branch lines and small country stations in 1964 in their song "Slow Train

"; another song which remembers Beeching is The Beeching Report, a song against the Beeching Axe, recorded by the post-rock

group iLiKETRAiNS

.

Physicist

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole...

and engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

. He became infamous in Britain in the early 1960s for his report "The Reshaping of British Railways", commonly referred to as the Beeching Report, which led to far-reaching changes in the railway network, popularly known as the Beeching Axe

Beeching Axe

The Beeching Axe or the Beeching Cuts are informal names for the British Government's attempt in the 1960s to reduce the cost of running British Railways, the nationalised railway system in the United Kingdom. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr Richard...

. As a result of the report, just over 4,000 route miles were cut on cost and efficiency grounds, leaving Britain with 13721 miles (22,081.8 km) of railway lines in 1966. A further 2000 miles (3,218.7 km) were to be lost by the end of the 1960s.

Early years

Beeching was born in SheernessSheerness

Sheerness is a town located beside the mouth of the River Medway on the northwest corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 12,000 it is the largest town on the island....

on the Isle of Sheppey

Isle of Sheppey

The Isle of Sheppey is an island off the northern coast of Kent, England in the Thames Estuary, some to the east of London. It has an area of . The island forms part of the local government district of Swale...

in Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, the second of four brothers. His father was a reporter with the Kent Messenger

Kent Messenger

This article is about the weekly paper for the Maidstone region. For the Kent Messenger Group, see KM Group.The Kent Messenger is a weekly newspaper serving the mid-Kent area. It is published in three editions - Maidstone, Malling, and the Weald...

, his mother a schoolteacher and his maternal grandfather a dockyard worker. Shortly after his birth, Beeching's family moved to Maidstone

Maidstone

Maidstone is the county town of Kent, England, south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town linking Maidstone to Rochester and the Thames Estuary. Historically, the river was a source and route for much of the town's trade. Maidstone was the centre of the agricultural...

where his brothers Kenneth (who was killed in the Second World War) and John were born. All four Beeching boys attended the local Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

primary school, Maidstone All Saints, and won scholarships to Maidstone Grammar School

Maidstone Grammar School

Maidstone Grammar School is a grammar school located in Maidstone, United Kingdom. It was founded in 1549.-Admissions:The school takes boys at the age of 11 and over by examination and boys and girls at 16+ on their GCSE results. The school currently has almost 1200 students and approximately 120...

, where Richard was a prefect. Beeching and his elder brother Geoffrey attended Imperial College of Science & Technology

Imperial College London

Imperial College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom, specialising in science, engineering, business and medicine...

in London where both read physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

and took First Class honours degrees. His younger brothers both attended Downing College, Cambridge

Downing College, Cambridge

Downing College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1800 and currently has around 650 students.- History :...

.

Beeching remained at Imperial College where he undertook a research Ph.D under the supervision of Sir George Thomson

George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson, FRS was an English physicist and Nobel laureate in physics recognised for his discovery with Clinton Davisson of the wave properties of the electron by electron diffraction.-Biography:...

. He continued in research until 1943, first at the Fuel Research Station in Greenwich

Greenwich

Greenwich is a district of south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich.Greenwich is best known for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time...

in 1936 and then, the following year, with the Mond Nickel Laboratories

Mond Nickel Company

The Mond Nickel Company Limited was a United Kingdom-based mining company, formed on September 20, 1900, licenced in Canada to carry on business in the province of Ontario, from October 16, 1900...

in London where he was appointed senior physicist carrying out research in the fields of physics, metallurgy

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their intermetallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are called alloys. It is also the technology of metals: the way in which science is applied to their practical use...

and mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is a discipline of engineering that applies the principles of physics and materials science for analysis, design, manufacturing, and maintenance of mechanical systems. It is the branch of engineering that involves the production and usage of heat and mechanical power for the...

.

In 1938 he married Ella Margaret Tiley whom he had known since his schooldays. They remained married for the rest of his life. They had no children and initially set up home in Solihull

Solihull

Solihull is a town in the West Midlands of England with a population of 94,753. It is a part of the West Midlands conurbation and is located 9 miles southeast of Birmingham city centre...

. During the Second World War Beeching, at the age of 29, was loaned by Mond Nickel on the recommendation of a Dr. Sykes at Firth Brown Steels

Firth Brown Steels

Firth Brown Steels was initially formed in 1902, when Sheffield steelmakers John Brown and Company exchanged shares and came to a working agreement with neighbouring company Thomas Firth & Sons...

to the Ministry of Supply

Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply was a department of the UK Government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. There was, however, a separate ministry responsible for aircraft production and the Admiralty retained...

, where he worked in their Armament Design and Research Departments at Fort Halstead

Fort Halstead

Fort Halstead is a research site of Dstl, an Executive Agency of the UK Ministry of Defence. It is situated on the crest of the Kentish North Downs, overlooking the town of Sevenoaks...

. His first post was with the Shell Design Section where he had a rank equivalent to that of army captain. Whilst with Armament Design, Beeching worked under the Department's Superintendent and Chief Engineer, Sir Frank Smith

Frank Edward Smith

Sir Frank Edward Smith, GCB, GBE, FRS was a British physicist.He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1918. His candidacy citation read: "Principal Assistant in the National Physical Laboratory . Author of a number of papers dealing with electrical units which have appeared in the...

, a former Chief Engineer with Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries was a British chemical company, taken over by AkzoNobel, a Dutch conglomerate, one of the largest chemical producers in the world. In its heyday, ICI was the largest manufacturing company in the British Empire, and commonly regarded as a "bellwether of the British...

(ICI).

After the war Smith returned to ICI as Technical Director and was replaced as Chief Engineer of Armament Design by Sir Steuart Mitchell who promoted Beeching, then 33 years old, to the post of Deputy Chief Engineer with a rank equivalent to that of Brigadier

Brigadier

Brigadier is a senior military rank, the meaning of which is somewhat different in different military services. The brigadier rank is generally superior to the rank of colonel, and subordinate to major general....

. Beeching continued his work with armaments, particularly anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare

NATO defines air defence as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action." They include ground and air based weapon systems, associated sensor systems, command and control arrangements and passive measures. It may be to protect naval, ground and air forces...

weaponry and small arms

Small arms

Small arms is a term of art used by armed forces to denote infantry weapons an individual soldier may carry. The description is usually limited to revolvers, pistols, submachine guns, carbines, assault rifles, battle rifles, multiple barrel firearms, sniper rifles, squad automatic weapons, light...

. In 1948 he joined ICI as Personal Technical Assistant to Sir Frank Smith where he remained for around 18 months, working on the production lines for various products such as zip fasteners, paints and leather

Leather

Leather is a durable and flexible material created via the tanning of putrescible animal rawhide and skin, primarily cattlehide. It can be produced through different manufacturing processes, ranging from cottage industry to heavy industry.-Forms:...

cloth with a view to improving efficiency and reducing production costs. He was then appointed to the Terylene Council, and subsequently to the board of ICI Fibres Division. In 1953 he went to Canada as vice-president of ICI (Canada) Ltd and given overall responsibility for a terylene plant in Ontario

Ontario

Ontario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

. He returned after two years to become chairman of ICI Metals Division on the recommendation of Sir Frank Smith. In 1957 he was appointed to the ICI board as Technical Director, and for a short time also served as Development Director.

Stedeford Committee

Sir Frank Smith, who had retired in 1959, was asked by the ConservativeConservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

Minister of Transport

Secretary of State for Transport

The Secretary of State for Transport is the member of the cabinet responsible for the British Department for Transport. The role has had a high turnover as new appointments are blamed for the failures of decades of their predecessors...

, Ernest Marples

Ernest Marples

Alfred Ernest Marples, Baron Marples PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Postmaster General and Minister of Transport. After his retirement from active politics in 1974 Marples was elevated to the peerage...

, to become a member of an advisory group on the financial state of the British Transport Commission

British Transport Commission

The British Transport Commission was created by Clement Attlee's post-war Labour government as a part of its nationalisation programme, to oversee railways, canals and road freight transport in Great Britain...

to be chaired by Sir Ivan Stedeford

Ivan Stedeford

Sir Ivan Arthur Rice Stedeford, GBE was a British industrialist and philanthropist.Stedeford was Chairman and Managing Director of Tube Investments and one of Britain's leading 20th-century industrialists....

. Smith declined but recommended Beeching in his place, a suggestion which Marples accepted. Stedeford and Beeching clashed on a number of issues connected with Beeching's proposal to drastically prune Britain's rail infrastructure. In spite of questions being asked in Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

, Sir Ivan's report was not published until much later.

British Rail Chairman

On 15 March 1961 Ernest MarplesErnest Marples

Alfred Ernest Marples, Baron Marples PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Postmaster General and Minister of Transport. After his retirement from active politics in 1974 Marples was elevated to the peerage...

announced in the House of Commons that Beeching would be the first Chairman of the British Railways Board

British Railways Board

The British Railways Board was a nationalised industry in the United Kingdom that existed from 1962 to 2001. From its foundation until 1997, it was responsible for most railway services in Great Britain, trading under the brand names British Railways and, from 1965, British Rail...

as from 1 June. The Board was the successor to the British Transport Commission

British Transport Commission

The British Transport Commission was created by Clement Attlee's post-war Labour government as a part of its nationalisation programme, to oversee railways, canals and road freight transport in Great Britain...

which was broken up by the Transport Act 1962

Transport Act 1962

The Transport Act 1962 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Described as the "most momentous piece of legislation in the field of railway law to have been enacted since the Railway and Canal Traffic Act 1854", it was passed by Harold Macmillan's Conservative government to dissolve the...

. Beeching would receive the same yearly salary that he was earning at I.C.I., the controversial sum of £24,000 (£367,000 in today's money), £10,000 more than Sir Brian Robertson

Brian Robertson, 1st Baron Robertson of Oakridge

General Brian Hubert Robertson, 1st Baron Robertson of Oakridge, GCB, GBE, KCMG, KCVO, DSO, MC , known as Sir Brian Robertson, 2nd Baronet, from 1933 to 1961, was a British Army General....

, the last chairman of the British Transport Commission, £14,000 more than Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

and two-and-a-half times higher than the salary of any head of a nationalised industry at the time. Beeching was given a leave of absence for five years by ICI in order to carry out this task.

At that time the Government was seeking outside talent and fresh blood to sort out the huge problems of the railway network.

There was widespread concern at the time that, despite substantial investment in the 1955 Modernisation Plan, the railways continued to haemorrhage losses - from £15.6m in 1956 to £42m in 1960. Passenger and goods traffic was also declining in the face of increased competition from the roads; by 1960, one in nine families owned a car. It would be Beeching's task to find a way to returning the industry to profitability as soon as possible.

First Beeching Report

On 27 March 1963, Beeching published his report on the future of the railways. Entitled "The Reshaping of British Railways", he called for the closure of one-third of the country's 7,000 railway stations. Passenger services would be withdrawn from around 5,000 route miles accounting for an annual train mileage of 68 million and yielding, according to Beeching, a net saving of £18m per year. The reshaping would also involve the shedding of around 70,000 British Railways jobs over three years. Beeching forecast that his changes would result in an improvement in British Railway's accounts of between £115m and £147m. The cut-backs would include the scrapping of a third of a million goods wagons, much as Stedeford had foreseen and fought against. See Gourvish (link below)Unsurprisingly, Beeching's plans were hugely controversial not only with trade unions, but with the Labour

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

opposition and railway-using public. Beeching was undeterred and argued that too many lines were running at a loss, and that his charge to shape a profitable railway made cuts a logical starting point. As one author puts it, Beeching "was expected to produce quick solutions to problems that were deep-seated and not susceptible to purely intellectual analysis." For his part, Beeching was unrepentant about his role in the closures: "I suppose I'll always be looked upon as the axe man, but it was surgery, not mad chopping."

Beeching was nevertheless instrumental in modernising many aspects of the railway network, particularly a greater emphasis on block trains which did not require expensive and time-consuming shunting en route.

On 23 December 1964, Tom Fraser

Tom Fraser

Tom Fraser PC was a Labour Member of Parliament for the Hamilton constituency between 1943 and 1967.He was Minister of Transport from October 16, 1964 until December 23, 1965...

informed the House of Commons that Beeching was to return to ICI in June 1965.

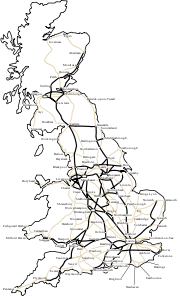

Second Beeching Report

On 16 February 1965, Beeching announced the second stage of his reorganisation of the railways. The report set out his conclusion that of the 7500 miles (12,070.1 km) of trunk railway throughout Britain, only 3000 miles (4,828 km) "should be selected for future development" and invested in. This policy would result in traffic through Britain being routed through nine selected lines. Traffic to BirminghamBirmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

, Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

and Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

would be routed through the West Coast Main Line

West Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line is the busiest mixed-traffic railway route in Britain, being the country's most important rail backbone in terms of population served. Fast, long-distance inter-city passenger services are provided between London, the West Midlands, the North West, North Wales and the...

running to Carlisle

Carlisle railway station

Carlisle railway station, also known as Carlisle Citadel station, is a railway station whichserves the Cumbrian City of Carlisle, England, and is a major station on the West Coast Main Line, lying south of Glasgow Central, and north of London Euston...

and Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

; traffic to the north-east would be concentrated through the East Coast Main Line

East Coast Main Line

The East Coast Main Line is a long electrified high-speed railway link between London, Peterborough, Doncaster, Wakefield, Leeds, York, Darlington, Newcastle and Edinburgh...

which was to be closed north of Newcastle; and traffic to Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

and the West Country

West Country

The West Country is an informal term for the area of south western England roughly corresponding to the modern South West England government region. It is often defined to encompass the historic counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset and the City of Bristol, while the counties of...

would go on the Great Western Main Line

Great Western Main Line

The Great Western Main Line is a main line railway in Great Britain that runs westwards from London Paddington station to the west of England and South Wales. The core Great Western Main Line runs from London Paddington to Temple Meads railway station in Bristol. A major branch of the Great...

, then to Swansea

Swansea

Swansea is a coastal city and county in Wales. Swansea is in the historic county boundaries of Glamorgan. Situated on the sandy South West Wales coast, the county area includes the Gower Peninsula and the Lliw uplands...

and Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

. Underpinning Beeching's proposals was his belief that there was still too much duplication in the railway network. Of the 7500 miles (12,070.1 km) of trunk route, 3700 miles (5,954.6 km) involves a choice between two routes, 700 miles (1,126.5 km) a choice of three, and over a further 700 miles (1,126.5 km) a choice of four.

These proposals were rejected by the government which put an early end to his secondment from ICI to which he returned in June 1965. It is a matter of debate whether Beeching left by mutual arrangement with the government or if he was sacked. Frank Cousins

Frank Cousins

Frank Cousins PC was a British trade union leader and Labour politician.He was born in Bulwell, Nottinghamshire, and became a full-time official in the road transport section of the Transport and General Workers' Union in July 1938...

, the Labour Minister of Technology

Minister of Technology

The Minister of Technology was a position in the government of the United Kingdom, sometimes abbreviated as "MinTech". The Ministry of Technology was established by the incoming government of Harold Wilson in October 1964 as part of Wilson's ambition to modernise the state for what he perceived to...

, revealed to the House of Commons in November 1965 that Beeching had been dismissed by Tom Fraser

Tom Fraser

Tom Fraser PC was a Labour Member of Parliament for the Hamilton constituency between 1943 and 1967.He was Minister of Transport from October 16, 1964 until December 23, 1965...

. Beeching denied this, pointing out that he had returned early to ICI as he would not have had enough time to undertake an in-depth transport study before the formal end of his secondment from ICI.

Later years

Upon returning to ICI, Beeching was appointed liaison director for the agricultural division and organisation and services director. He later rose to become Deputy Chairman from 1966-68. In the 1965 birthday honoursQueen's Birthday Honours

The Queen's Birthday Honours is a part of the British honours system, being a civic occasion on the celebration of the Queen's Official Birthday in which new members of most Commonwealth Realms honours are named. The awards are presented by the reigning monarch or head of state, currently Queen...

he was made a life peer

Life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the Peerage whose titles cannot be inherited. Nowadays life peerages, always of baronial rank, are created under the Life Peerages Act 1958 and entitle the holders to seats in the House of Lords, presuming they meet qualifications such as...

as Baron Beeching, of East Grinstead

East Grinstead

East Grinstead is a town and civil parish in the northeastern corner of Mid Sussex, West Sussex in England near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders. It lies south of London, north northeast of Brighton, and east northeast of the county town of Chichester...

in the county of Sussex

Sussex

Sussex , from the Old English Sūþsēaxe , is an historic county in South East England corresponding roughly in area to the ancient Kingdom of Sussex. It is bounded on the north by Surrey, east by Kent, south by the English Channel, and west by Hampshire, and is divided for local government into West...

, and in the same year he became a director of Lloyds Bank

Lloyds Bank

Lloyds Bank Plc was a British retail bank which operated in England and Wales from 1765 until its merger into Lloyds TSB in 1995; it remains a registered company but is currently dormant. It expanded during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and took over a number of smaller banking companies...

. In 1966 he was appointed as chairman of the Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

to examine assizes and quarter sessions, and eventually proposed a mass reorganisation of the court system involving the setting-up of regional courts in cities such as Cardiff

Cardiff

Cardiff is the capital, largest city and most populous county of Wales and the 10th largest city in the United Kingdom. The city is Wales' chief commercial centre, the base for most national cultural and sporting institutions, the Welsh national media, and the seat of the National Assembly for...

, Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

and Leeds

Leeds

Leeds is a city and metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. In 2001 Leeds' main urban subdivision had a population of 443,247, while the entire city has a population of 798,800 , making it the 30th-most populous city in the European Union.Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial...

. The following year he became chairman of Associated Electrical Industries

Associated Electrical Industries

Associated Electrical Industries was a British holding company formed in 1928 through the merger of the British Thomson-Houston Company and Metropolitan-Vickers electrical engineering companies...

, a role he also held with Redland

Redland plc

Redland plc was a leading British building materials business. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange and was once a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index.-History:...

from 1970–77 and Furness Withy

Furness Withy

Furness Withy was a major British transport business. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange.-History:The Company was founded by Christopher Furness and Henry Withy in 1891 in Hartlepool. This was achieved by the amalgamation of the Furness Line of steamers with the business of Edward Withy and...

from 1973-75.

The Beatles

The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, active throughout the 1960s and one of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed acts in the history of popular music. Formed in Liverpool, by 1962 the group consisted of John Lennon , Paul McCartney , George Harrison and Ringo Starr...

considered Lord Beeching when they were trying to find someone who could sort out the business affairs of their company Apple Corps

Apple Corps

Apple Corps Ltd. is a multi-armed multimedia corporation founded in January 1968 by the members of The Beatles to replace their earlier company and to form a conglomerate. Its name is a pun. Its chief division is Apple Records, which was launched in the same year...

.

Legacy

Beeching's findings have been reviewed in two books by his contemporaries. R.H.N (Dick) Hardy: Beeching - Champion of the Railway (1989) ISBN 0-7110-1855-3 and Gerard FiennesGerry Fiennes

Gerry Fiennes was a British railway manager who rose through the ranks of the London and North Eastern Railway and later British Rail following graduation from Oxford University.He joined the London and North Eastern Railway as a Traffic Apprentice in 1928, and his subsequent...

: I Tried to Run a Railway (1967) ISBN 0-7110-0447-1. Neither book is in print at the time of writing (2006). Both are broadly sympathetic to Beeching's basic analysis and the proposed solution. On the other hand, Hardy points out Beeching's political naivete (see below) in moving from private to public industry. Similarly Fiennes notes that because a passenger service was producing a loss did not mean that it must always do so in future. It can reasonably be argued that too many routes were run in a traditional fashion unchanged from Edwardian Britain, whereas radical changes in operating procedures would have greatly reduced the losses generated. Beeching allegedly made no attempt to quantify what such savings could have yielded, nor which lines could have survived had practices been changed.

The political aspects of the Beeching Report remain controversial. The report was commissioned by a Conservative government with strong ties to the road construction lobby. However, the report's findings were enthusiastically endorsed and implemented by the subsequent Labour administrations which were heavily dependent for funds from unions associated with road industry associations. The general reduction of Britain's railway mileage was probably inevitable but the speed with which the two Labour governments of 1964 and 1966 pursued the report's recommendations was not. Beeching seemingly failed to realise that history would portray him as the 'axeman', even though the Secretary of State for Transport

Secretary of State for Transport

The Secretary of State for Transport is the member of the cabinet responsible for the British Department for Transport. The role has had a high turnover as new appointments are blamed for the failures of decades of their predecessors...

is the only person who can authorise abandonment of railway passenger services in the UK.

Several ex-railway sites have been named after Beeching. There is a pub called Lord Beechings at the end of the Cambrian Railway at Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth is a historic market town, administrative centre and holiday resort within Ceredigion, Wales. Often colloquially known as Aber, it is located at the confluence of the rivers Ystwyth and Rheidol....

, which until its refurbishment by SA Brain & Company Ltd was decorated with various railway memorabilia, in particular regarding the Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth is a historic market town, administrative centre and holiday resort within Ceredigion, Wales. Often colloquially known as Aber, it is located at the confluence of the rivers Ystwyth and Rheidol....

- London and Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth is a historic market town, administrative centre and holiday resort within Ceredigion, Wales. Often colloquially known as Aber, it is located at the confluence of the rivers Ystwyth and Rheidol....

- Carmarthen

Carmarthen

Carmarthen is a community in, and the county town of, Carmarthenshire, Wales. It is sited on the River Towy north of its mouth at Carmarthen Bay. In 2001, the population was 14,648....

service, which he axed. It was previously called The Railway. The road Beechings Way at Alford, Lincolnshire

Alford, Lincolnshire

- Notable residents :* Captain John Smith who lived in nearby Willoughby* Anne Hutchinson, pioneer settler and religious reformer in the United States* Thomas Paine, who was an excise officer in the town....

, is so named to commemorate the loss of the formerly adjacent station and line (formerly from Grimsby

Grimsby

Grimsby is a seaport on the Humber Estuary in Lincolnshire, England. It has been the administrative centre of the unitary authority area of North East Lincolnshire since 1996...

to London, via Louth

Louth, Lincolnshire

Louth is a market town and civil parish within the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England.-Geography:Known as the "capital of the Lincolnshire Wolds", it is situated where the ancient trackway Barton Street crosses the River Lud, and has a total resident population of 15,930.The Greenwich...

and Peterborough

Peterborough

Peterborough is a cathedral city and unitary authority area in the East of England, with an estimated population of in June 2007. For ceremonial purposes it is in the county of Cambridgeshire. Situated north of London, the city stands on the River Nene which flows into the North Sea...

) under the Beeching Axe

Beeching Axe

The Beeching Axe or the Beeching Cuts are informal names for the British Government's attempt in the 1960s to reduce the cost of running British Railways, the nationalised railway system in the United Kingdom. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr Richard...

. The road 'Beeching Drive' in Lowestoft

Lowestoft

Lowestoft is a town in the English county of Suffolk. The town is on the North Sea coast and is the most easterly point of the United Kingdom. It is north-east of London, north-east of Ipswich and south-east of Norwich...

, Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, located on the site of the former Lowestoft North station is also so named. Coincidentally, a smaller pedestrian area in the vicinity is known as 'Stevenson's Walk'. There is a cul-de-sac in the Leicestershire

Leicestershire

Leicestershire is a landlocked county in the English Midlands. It takes its name from the heavily populated City of Leicester, traditionally its administrative centre, although the City of Leicester unitary authority is today administered separately from the rest of Leicestershire...

village of Countesthorpe

Countesthorpe

Countesthorpe is a large village and civil parish in the Leicestershire district of Blaby, with a population of 6,393 . It lies to the south of Leicester, and is about six miles from the city centre, but only two miles south of the suburb of South Wigston...

[about seven miles (11 km) south of Leicester

Leicester

Leicester is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England, and the county town of Leicestershire. The city lies on the River Soar and at the edge of the National Forest...

city centre] aptly named Beeching's Close. The village was served by a line between Leicester and Rugby

Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in Warwickshire, England, located on the River Avon. The town has a population of 61,988 making it the second largest town in the county...

, closed under the Beeching Axe

Beeching Axe

The Beeching Axe or the Beeching Cuts are informal names for the British Government's attempt in the 1960s to reduce the cost of running British Railways, the nationalised railway system in the United Kingdom. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr Richard...

. The gardens of the houses on the west side of the close meet with the boundary of the old line. East Grinstead, where Beeching lived, was formerly served by a railway line from Tunbridge Wells (West) to Three Bridges, a line most of which was closed under the Beeching Axe

Beeching Axe

The Beeching Axe or the Beeching Cuts are informal names for the British Government's attempt in the 1960s to reduce the cost of running British Railways, the nationalised railway system in the United Kingdom. The name is that of the main author of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr Richard...

. To the east of the current East Grinstead station, the line passed through a deep cutting. This cutting currently forms part of the A22 relief road through East Grinstead. Due to the depth of the cutting, locals wanted to call the road "Beeching Cut", but as this was deemed politically incorrect, it was instead called 'Beeching Way' .

In popular culture

The effect of the 'Beeching Axe' on a small station was the subject of Oh, Doctor Beeching!Oh, Doctor Beeching!

Oh, Doctor Beeching! is a British television sitcom written by David Croft and Richard Spendlove, which, after a broadcast pilot on 14 August 1995, ran for two series from 8 July 1996, with the last episode being broadcast on 28 September 1997...

, a television sitcom by David Croft and Richard Spendlove

Richard Spendlove

Richard Spendlove MBE is a British radio producer/presenter and television writer.-Life and work:Richard Spendlove worked for the former British Railways for 35 years, and in 1963 was appointed Relief Station Master at Cambridge, one of the youngest men in that job...

from 1995 to 1997.

A popular Flanagan

Bud Flanagan

Bud Flanagan was a popular English music hall and vaudeville entertainer from the 1930s until the 1960s. Flanagan was famous as a wartime entertainer and his achievements were recognised when he was awarded the O.B.E. in 1960.- Family background :Flaganan was born Chaim Reuben Weintrop in...

and Allen

Chesney Allen

Chesney Allen was a popular English entertainer of the Second World War period. He is best remembered as part of the double act with Bud Flanagan, Flanagan and Allen.-Life and career:...

song became the theme song which ran:

- "Oh! Dr. Beeching, what have you done?

- There once were lots of trains to catch, but soon there will be none!

- I'll have to buy a bike, 'cause I can't afford a car.

- Oh! Dr. Beeching! What a naughty man you are!"

Note: This is based on the once-well-known and railway-related poem.

- "Oh! Mr porter, what can I do!

- I wanted to go to Birmingham and they took me on to Crewe.

- Take me back to London as quickly as you can

- Oh Mr Porter what a silly girl I am!"

Flanders and Swann

Flanders and Swann

The British duo Flanders and Swann were the actor and singer Michael Flanders and the composer, pianist and linguist Donald Swann , who collaborated in writing and performing comic songs....

commemorated the loss of the branch lines and small country stations in 1964 in their song "Slow Train

Slow Train

"Slow Train" is a song by the British duo Flanders and Swann, written in 1963.It laments the loss of British stations and railway lines in that era, due to the Beeching cuts, and also the passing of a way of life, with the advent of motorways etc....

"; another song which remembers Beeching is The Beeching Report, a song against the Beeching Axe, recorded by the post-rock

Post-rock

Post-rock is a subgenre of rock music characterized by the influence and use of instruments commonly associated with rock, but using rhythms and "guitars as facilitators of timbre and textures" not traditionally found in rock...

group iLiKETRAiNS

ILiKETRAiNS

I Like Trains are an alternative/post-rock band from Leeds, England. The group play brooding songs featuring sparse piano and guitar, baritone vocals, uplifting choral passages and reverberant orchestral crescendos...

.