Bird colony

Encyclopedia

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of bird

Bird

Birds are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic , egg-laying, vertebrate animals. Around 10,000 living species and 188 families makes them the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. They inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from...

that nest

Bird nest

A bird nest is the spot in which a bird lays and incubates its eggs and raises its young. Although the term popularly refers to a specific structure made by the bird itself—such as the grassy cup nest of the American Robin or Eurasian Blackbird, or the elaborately woven hanging nest of the...

or roost in close proximity at a particular location. Many kinds of birds are known to congregate in groups of varying size; a congregation of nesting birds is called a breeding colony. Colonial nesting birds include seabirds such as auk

Auk

An auk is a bird of the family Alcidae in the order Charadriiformes. Auks are superficially similar to penguins due to their black-and-white colours, their upright posture and some of their habits...

s and albatross

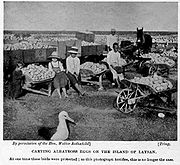

Albatross

Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm-petrels and diving-petrels in the order Procellariiformes . They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific...

es; wetland species such as heron

Heron

The herons are long-legged freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae. There are 64 recognised species in this family. Some are called "egrets" or "bitterns" instead of "heron"....

s; and a few passerine

Passerine

A passerine is a bird of the order Passeriformes, which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds or, less accurately, as songbirds, the passerines form one of the most diverse terrestrial vertebrate orders: with over 5,000 identified species, it has roughly...

s such as weaverbirds, certain blackbird

Icterid

The Icterids are a group of small to medium-sized, often colorful passerine birds restricted to the New World. Most species have black as a predominant plumage color, often enlivened by yellow, orange or red. The family is extremely varied in size, shape, behavior and coloration...

s, and some swallow

Swallow

The swallows and martins are a group of passerine birds in the family Hirundinidae which are characterised by their adaptation to aerial feeding...

s. A group of birds congregating for rest is called a communal roost

Communal roosting

Communal roosting is practiced by birds when large flocks or colonies roost together usually in trees with several hundred on each.Several communal roosting trees can be located within densely populated cities nowadays where common birds like house sparrows and starlings etc...

.

Variations on colonial nesting in birds

Approximately 13% of all bird species nest colonially.Nesting colonies are very common among seabirds on cliffs and islands. Nearly 95% of seabirds are colonial, leading to the usage, seabird colony, sometimes called a rookery

Rookery

A rookery is a colony of breeding animals, generally birds. A rook is a Northern European and Central Asian member of the crow family, which nest in prominent colonies at the tops of trees. The term is applied to the nesting place of birds, such as crows and rooks, the source of the term...

. Many species of tern

Tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Sternidae, previously considered a subfamily of the gull family Laridae . They form a lineage with the gulls and skimmers which in turn is related to skuas and auks...

s nest in colonies on the ground. Heron

Heron

The herons are long-legged freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae. There are 64 recognised species in this family. Some are called "egrets" or "bitterns" instead of "heron"....

s, egrets, stork

Stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family Ciconiidae. They are the only family in the biological order Ciconiiformes, which was once much larger and held a number of families....

s, and other large waterfowl also nest communally in what are called heronries

Heronry

A heronry is a breeding ground for herons, sometimes called a heron rookery.- Asia :* Kaggaladu Heronry is in Karnataka state of India...

. Colony nesting may be an evolutionary response to a shortage of safe nesting sites and abundance or unpredictable food sources which are far away from the nest sites. Colony-nesting birds often show synchrony in their breeding, meaning that chicks all hatch at once, with the implication that any predator coming along at that time would find more prey items than it could possibly eat.

What exactly constitutes a colony is a matter of definition. Tufted Puffins, for example, are pelagic birds that nest on the steep slopes and rocky crevices on coastal cliffs, often on islands. Each pair excavates its own burrow. A congregation of puffin burrows on a marine island is considered a colony. Sand Martin

Sand Martin

The Sand Martin is a migratory passerine bird in the swallow family. It has a wide range in summer, embracing practically the whole of Europe and the Mediterranean countries, part of northern Asia and also North America. It winters in eastern and southern Africa, South America and South Asia...

s (called Bank Swallows in North America) are seldom, if ever, observed to nest in solitude; such a dependence on social nesting would term the bird a colonial nester. A more extreme example of colonial nesting is found in the weaverbird family. The Sociable Weaver

Sociable Weaver

The Sociable Weaver or Social Weaver is a species of bird in the Ploceidae family endemic to Southern Africa. It is monotypic within the genus Philetairus. It is found in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. but their range is centred around Northern Cape Province and southern Namibia...

of southern Africa constructs massive, multi-family dwellings of twigs and dry grasses, with many entrances leading to different nesting chambers, accommodating as many as a hundred nesting pairs. These structures resemble haystacks hanging from trees, and have been likened to apartment buildings or beehives.

Some seabird colonies host thousands of nesting pairs of various species. Triangle Island, for example, the largest seabird colony in British Columbia

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

, Canada, is home to auks, gulls, cormorants, shorebirds, and other birds, as well as some marine mammals. Many seabirds show remarkable site fidelity, returning to the same burrow, nest or site for many years, and they will defend that site from rivals with great vigour. This increases breeding success, provides a place for returning mates to reunite, and reduces the costs of prospecting for a new site. Young adults breeding for the first time usually return to their natal colony, and often nest very close to where they hatched. Individual nesting sites at seabird colonies can be widely spaced, as in an albatross colony, or densely packed like an auk colony. In most seabird colonies several different species will nest on the same colony, often exhibiting some niche

Ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is a term describing the relational position of a species or population in its ecosystem to each other; e.g. a dolphin could potentially be in another ecological niche from one that travels in a different pod if the members of these pods utilize significantly different food...

separation. Seabirds can nest in trees (if any are available), on the ground (with or without nests), on cliffs, in burrows under the ground and in rocky crevices. Colony size

Group size measures

Many animals, including humans, tend to live in groups, herds, flocks, bands, packs, shoals, or colonies of conspecific individuals. The size of these groups, as expressed by the number of participant individuals, is an important aspect of their social environment...

is a major aspect of the social environment of colonial birds.

Some birds are known to nest in colonies when conditions are suitable, but not always. The White-winged Dove

White-winged Dove

The White-winged Dove is a dove whose native range extends from the south-western USA through Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In recent years with increasing urbanization and backyard feeding, it has expanded throughout Texas and into Louisiana...

of southwestern North America was known to nest in large colonies when foraging areas could support such numbers. In 1978, in Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Tamaulipas is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 43 municipalities and its capital city is Ciudad Victoria. The capital city was named after Guadalupe Victoria, the...

, Mexico, researchers counted 22 breeding colonies of White-winged Doves with a collective population size of more than eight million birds. But as habitat was transformed through urbanization or agriculture, the doves apparently spread out into smaller, less long-lived colonies. Today, these doves are observed to nest singly and colonially in both urban and rural areas.

The term colony has also been applied, perhaps misleadingly, to smaller nesting groups, such as forest-dwelling species that nest socially in a suitable stand of trees. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker

Red-cockaded Woodpecker

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker is a woodpecker found in southeastern North America.- Description :About the size of the Northern Cardinal, it is approximately 8.5 in. long, with a wingspan of about 14 in. and a weight of about 1.5 ounces...

, an endangered species of southeastern North America, is a social species that feeds and roosts in family groups, or clans. Clans nest and roost in clusters of tree cavities and use a cooperative breeding

Cooperative breeding

Cooperative breeding is a social system in which individuals contribute care to offspring that are not their own at the expense of their own reproduction . When reproduction is monopolized by one or few of the adult group members and most adults do not reproduce, but help rear the breeder’s...

system. Many parrot

Parrot

Parrots, also known as psittacines , are birds of the roughly 372 species in 86 genera that make up the order Psittaciformes, found in most tropical and subtropical regions. The order is subdivided into three families: the Psittacidae , the Cacatuidae and the Strigopidae...

species are also extremely social. For example, the Thick-billed Parrot

Thick-billed Parrot

The Thick-billed Parrot, Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha is an endangered, medium-sized, up to 38 cm long, bright green parrot with a large black bill and a red forecrown, shoulder and thighs...

is another bird that nests and roosts communally; individuals of neighboring roosts has been observed to communicate with each other each morning to signal their readiness to form flocks

Flocking (behavior)

Flocking behavior is the behavior exhibited when a group of birds, called a flock, are foraging or in flight. There are parallels with the shoaling behavior of fish, the swarming behavior of insects, and herd behavior of land animals....

for foraging. However, these complex social structures in birds are a different sort of group behavior than what is normally considered colonial.

Ecological functions

The habit of nesting in groups is believed to provide better survival against predators in several ways. Many colonies are situated in locations that are naturally free of predators. In other cases, the presence of many birds means there are more individuals available for defense. Also, synchronized breeding leads to such an abundance of offspring as to satiate predatorsPredator satiation

Predator satiation is an antipredator adaptation in which prey occur at high population densities, reducing the probability of an individual organism being eaten....

.

For seabirds, colonies on islands have an obvious advantage over mainland colonies when it comes to protection from terrestrial predators. Other situations can also be found where bird colonies avoid predation. A study of Yellow-rumped Cacique

Yellow-rumped Cacique

The Yellow-rumped Cacique, Cacicus cela, is a passerine bird in the New World family Icteridae. It breeds in much of northern South America from Panama and Trinidad south to Peru, Bolivia and central Brazil.-Description:...

s in Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

found that the birds, which build enclosed, pouch-like nests in colonies of up to one hundred active nests, situate themselves near wasp nests, which provide some protection from tree-dwelling predators such as monkeys. When other birds came to rob the nests, the caciques would cooperatively defend the colony by mobbing the invader. Mobbing, clearly a group effort, is well-known behavior, not limited to colonial species; the more birds participating in the mobbing, the more effective it is at driving off the predator. Therefore, it has been theorized that the larger number of individuals available for vigilance and defense makes the colony a safer place for the individual birds nesting there. More pairs of eyes and ears are available to raise the alarm and rise to the occasion.

Another suggestion is that colonies act as information centers and birds that have not found good foraging sites are able to follow others, who have fared better, to find food. This makes sense for foragers because the food source is one that can be locally abundant. This hypothesis would explain why the Lesser Kestrel

Lesser Kestrel

The Lesser Kestrel is a small falcon. This species breeds from the Mediterranean across southern central Asia to China and Mongolia. It is a summer migrant, wintering in Africa and Pakistan and sometimes even to India and Iraq. It is rare north of its breeding range, and declining in its European...

, which feeds on insects, breeds in colonies, while the related Common Kestrel

Common Kestrel

The Common Kestrel is a bird of prey species belonging to the kestrel group of the falcon family Falconidae. It is also known as the European Kestrel, Eurasian Kestrel, or Old World Kestrel. In Britain, where no other brown falcon occurs, it is generally just called "the kestrel".This species...

, which feeds on larger prey, is not.

Colonial behaviour has its costs as well. It has been noted that parasitism

Parasitism

Parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship between organisms of different species where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Traditionally parasite referred to organisms with lifestages that needed more than one host . These are now called macroparasites...

by haematozoa

Haematozoa

Haematozoa or Hematozoa is a general term that includes blood parasites, mainly protozoans. Well known examples include the malaria and trypanosoma parasites, but a large number of species are known to infect birds and are transmitted by arthropod vectors....

is higher in colonial birds and it has been suggested that blood parasites might have shaped adaptations such as larger organs in the immune system and life-history traits. Other costs include brood parasitism and competition for food and territory. Colony size is a factor in the ecological function of colony nesting. In a larger colony, increased competition for food can make it harder for parents to feed their chicks.

The benefits and drawbacks for birds of nesting in groups seem to be highly situational. Although scientists have hypothesized about the advantages of group nesting in terms of enabling group defensive behavior, escape from predation by being surrounded by neighbors (called the selfish herd hypothesis), as well as escaping predators through sheer numbers, in reality, each of these functions evidently depends on a number of factors. Clearly, there can be safety in numbers, but there is some doubt about whether it balances out against the tendency for conspicuous breeding colonies to attract predators, and some suggest that colonial breeding can actually make birds more vulnerable. At a Common Tern

Common Tern

The Common Tern is a seabird of the tern family Sternidae. This bird has a circumpolar distribution, breeding in temperate and sub-Arctic regions of Europe, Asia and east and central North America. It is strongly migratory, wintering in coastal tropical and subtropical regions. It is sometimes...

colony in Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

, a study of Spotted Sandpiper

Spotted Sandpiper

The Spotted Sandpiper is a small shorebird, 18–20 cm long. Together with its sister species, the Common Sandpiper they make up the genus Actitis...

s observed to nest near the tern colony showed that the sandpipers that nested nearest the colony seemed to gain some protection from mammalian predators, but avian predators were apparently attracted to the colony and the sandpipers nesting there were actually more vulnerable. In a study of a Least Tern colony in Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

, nocturnal avian predators in the form of Black-crowned Night Heron

Black-crowned Night Heron

The Black-crowned Night Heron commonly abbreviated to just Night Heron in Eurasia, is a medium-sized heron found throughout a large part of the world, except in the coldest regions and Australasia .-Description:Adults are...

s and Great Horned Owl

Great Horned Owl

The Great Horned Owl, , also known as the Tiger Owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an adaptable bird with a vast range and is the most widely distributed true owl in the Americas.-Description:...

s were observed to repeatedly invade a colony, flying into the middle of the colony and meeting no resistance.

For seabirds, the location of colonies on islands, which are inaccessible to terrestrial predators, is an obvious advantage. Islands where terrestrial predators have arrived in the form of rats, cats, foxes, etc., have devastated island seabird colonies. One well-studied case of this phenomenon has been the effect on Common Murre colonies on islands in Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

, where foxes were introduced for fur farming

Fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of world market for in the early modern period furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most valued...

.

Human use

Guano

Guano is the excrement of seabirds, cave dwelling bats, and seals. Guano manure is an effective fertilizer due to its high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen and also its lack of odor. It was an important source of nitrates for gunpowder...

for fertilizer. Over-exploitation can be devastating to a colony, or even to an entire population of a colonial species. For example, there was once a large seabird known as the Great Auk

Great Auk

The Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis, formerly of the genus Alca, was a large, flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus, a group of birds that formerly included one other species of flightless giant auk from the Atlantic Ocean...

, which nested in colonies in the North Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

. Eggs and birds were used for a variety of purposes. Beginning in the 16th Century, seafarers took the birds in especially great numbers to fill ships' larders, and by the mid-19th century, the Great Auk was extinct. Likewise, the Short-tailed Albatross

Short-tailed Albatross

The Short-tailed Albatross or Steller's Albatross, Phoebastria albatrus, is a large rare seabird from the North Pacific. Although related to the other North Pacific albatrosses, it also exhibits behavioural and morphological links to the albatrosses of the Southern Ocean...

of the North Pacific

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

was heavily harvested at what seems to have been its primary colony on Torishima Island

Torishima (Izu Islands)

, literally meaning "Bird Island", is an uninhabited volcanic island at the south end of the Izu Islands in the Pacific Ocean, administered by Japan.-Geography:...

. Millions of birds were killed with a few decades at the end of the 19th century. It survives, though endangered. In North America, the case of the highly gregarious Passenger Pigeon

Passenger Pigeon

The Passenger Pigeon or Wild Pigeon was a bird, now extinct, that existed in North America and lived in enormous migratory flocks until the early 20th century...

has been well documented. It was hunted as if inexhaustible. Case in point: in 1871, in Wisconsin, an estimated 136 million pigeons nested in a dense congregation over a wide area; thousands of people were drawn to hunt the birds, shipping the squab

Squab (food)

In culinary terminology, squab is a young domestic pigeon or its meat. The meat is widely described as tasting like dark chicken. The term is probably of Scandinavian origin; the Swedish word skvabb means "loose, fat flesh". It formerly applied to all dove and pigeon species, such as the Wood...

to market by rail. The Passenger Pigeon is a famous example of a familiar bird going extinct in modern times.

The use of seabird droppings as fertilizer, or guano, began with the Indigenous Peruvians, who collected it from sites along the coast of South America, such as the Chincha Islands

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands are a group of three small islands 21 km off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco,...

. When, after the Spanish Conquest, the value of this fertilizer became known to the wider world, collection increased to the point where the supply nearly ran out, and other sources of guano had to be found.