Blackbirding

Encyclopedia

Kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the taking away or transportation of a person against that person's will, usually to hold the person in false imprisonment, a confinement without legal authority...

s to work as labourers. From the 1860s blackbirding ships were engaged in seeking workers to mine the guano

Guano

Guano is the excrement of seabirds, cave dwelling bats, and seals. Guano manure is an effective fertilizer due to its high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen and also its lack of odor. It was an important source of nitrates for gunpowder...

deposits on the Chincha Islands

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands are a group of three small islands 21 km off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco,...

in Peru. In the 1870s the blackbirding trade focused on supplying labourers to plantations, particularly the sugar cane plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

s of Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

(Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

) and Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

. The practice occurred primarily between the 1860s and 1901. Those 'blackbirded' were recruited from the indigenous populations of nearby Pacific islands or northern Queensland. In the early days of the pearling industry in Broome

Broome, Western Australia

Broome is a pearling and tourist town in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, north of Perth. The year round population is approximately 14,436, growing to more than 45,000 per month during the tourist season...

, local Aboriginal people were blackbirded from the surrounding areas, including aboriginal people from desert areas.

Blackbirding has continued to the present day in the Third World. One example is the kidnapping and coercion at gunpoint of indigenous people in Central America to work as plantation labourers, where they are exposed to heavy pesticide loads and do back-breaking work for very little pay.

Etymology

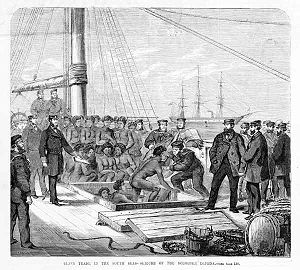

The term may have been formed directly as a contraction of blackbird catching; blackbird was a slang term for the local indigenous people. It might also have derived from an earlier phrase, blackbird shooting, which referred to recreational hunting of Australian Aboriginal people by early European settlers.Blackbirding in Polynesia in the 1860's

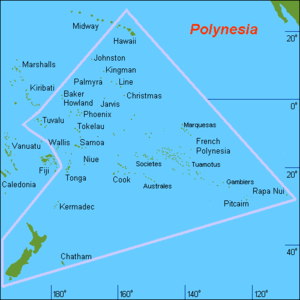

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

from Easter Island

Easter Island

Easter Island is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian triangle. A special territory of Chile that was annexed in 1888, Easter Island is famous for its 887 extant monumental statues, called moai, created by the early Rapanui people...

in the eastern Pacific to the southern islands of the Ellice Islands

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

(now Tuvalu

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

) in the central Pacific, seeking workers to mine the guano

Guano

Guano is the excrement of seabirds, cave dwelling bats, and seals. Guano manure is an effective fertilizer due to its high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen and also its lack of odor. It was an important source of nitrates for gunpowder...

deposits on the Chincha Islands

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands are a group of three small islands 21 km off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco,...

in Peru.

In 1862 the Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

vian government had decided to obtain indentured labourers to collect guano

Guano

Guano is the excrement of seabirds, cave dwelling bats, and seals. Guano manure is an effective fertilizer due to its high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen and also its lack of odor. It was an important source of nitrates for gunpowder...

on the Peru's Chincha Islands

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands are a group of three small islands 21 km off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco,...

. A fleet of ships spread out over the Pacific to find willing migrants, but quickly switched to plain kidnapping tactics instead. In June 1863 there lived about 350 people on Ata atoll in Tonga

Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga , is a state and an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, comprising 176 islands scattered over of ocean in the South Pacific...

in a village called Kolomaile (of which remnants were still visible a century later). Captain Thomas James McGrath of the whaler "Grecian", having decided that slavetrade was more profitable than whaling, came along and invited the islanders on board for trading. But once almost half of the population was on board, doors and rooms were locked, and the ship sailed away. 144 persons would never return. The "Grecian" tried to get more recruits from the Lau group, but was not successful there. From Niuafouou

Niuafo'ou

Niuafoou is the most northerly island in the kingdom of Tonga. It is a volcanic rim island of 15 km² and with a population of 650 in 2006.-Geography:...

it was able to fool only 30 people; the second island in Tonga

Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga , is a state and an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, comprising 176 islands scattered over of ocean in the South Pacific...

to be affected. (Uiha

'Uiha

Uiha is an island in Lifuka district, in the Haapai islands of Tonga. It had a population of 638 and an area of 5.36 km².More about Ha'apai at http://www.nelligennet.com/horst.com...

was the third, but there the islanders had actually been able to reverse roles and ambushed the ship the "Margarita" instead).

The "Grecian" never made it to Peru. Probably near Pukapuka (Tuamotu) it met another slaver, the "General Prim", which had left Callao

Callao

Callao is the largest and most important port in Peru. The city is coterminous with the Constitutional Province of Callao, the only province of the Callao Region. Callao is located west of Lima, the country's capital, and is part of the Lima Metropolitan Area, a large metropolis that holds almost...

in March, which was more than willing to take over the 174 Friendly islanders to quickly return to port, where it arrived on 19 July. Meanwhile, however, the Peruvian government, under pressure from foreign powers and also shocked that its labour plan had turned into a slavetrade, had already on 28 April cancelled all licenses. The islanders on board of the "General Prim", and other ships were even not allowed to enter Peruvian soil. They were transferred to other ships chartered by the Peruvian government to bring them home. By the time, 2 October 1863, the "Adelante" (on which the Tongans were put) finally left, many had already died or were dying from contagious diseases. It seems that Captain Escurra of the "Adelante" (which had been one of the most successful slavers before!) had not any intention to bring them home after being paid $30 per head. Instead he dumped them on uninhabited Cocos Island

Cocos Island

Cocos Island is an uninhabited island located off the shore of Costa Rica . It constitutes the 11th district of Puntarenas Canton of the province of Puntarenas. It is one of the National Parks of Costa Rica...

, (absolutely not on the route to Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

), claiming that the 426 kanakas

Kanakas

Kanaka was the term for a worker from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia , Fiji and Queensland in the 19th and early 20th centuries...

were affected with smallpox and a danger to his crew. 200 were left over there when the whaler "Active" passed along and found them on 21 October. Somewhere in November finally a Peruvian warship "Tumbes" came to save the survivors, of which there were 38 left. They were brought to Paita

Paita

Paita is a city in northwestern Peru. It is the capital of the Paita Province which is in the Piura Region. It is a leading seaport in that region...

, where they apparently were absorbed in the local population.

Meanwhile in Tonga, king George Tupou I, having heard of the happenings, sent three schooners to Ata to evacuate and to resettle the about 200 remaining people to Eua

'Eua

Eua is a smaller but still major island in the kingdom of Tonga. It is close to Tongatapu, but forms a separate administrative division. It has an area of 87.44 km2, and a population in 2006 of 5,165 people.- Geography :...

, where they would be safe against future attacks. Nowadays their descendants still live in Haatua of which a part has received the name Kolomaile.

The Rev. A. W. Murray, the earliest European missionary in Tuvalu, describes the activities of blackbirders in the Ellice Islands

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

, as persuading islanders onto the ships with the promise that they would be taught about God while engaged in coconut oil production, when the intended destination was the Chincha Islands

Chincha Islands

The Chincha Islands are a group of three small islands 21 km off the southwest coast of Peru, to which they belong, near the town of Pisco,...

in Peru. The impact of the blackbirders on the Ellice Islands

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

is established by the observations of the Rev. A Murray who reported that in 1863 about 180 people were taken from Funafuti

Funafuti

Funafuti is an atoll that forms the capital of the island nation of Tuvalu. It has a population of 4,492 , making it the most populated atoll in the country. It is a narrow sweep of land between 20 and 400 metres wide, encircling a large lagoon 18 km long and 14 km wide, with a surface of...

and about 200 were taken from Nukulaelae

Nukulaelae

Nukulaelae is an atoll that is part of the nation of Tuvalu, and has a population of 393. It has the form of an oval and consists of at least 15 islets...

as there were fewer than 100 of the 300 recorded in 1861 as living on Nukulaelae

Nukulaelae

Nukulaelae is an atoll that is part of the nation of Tuvalu, and has a population of 393. It has the form of an oval and consists of at least 15 islets...

.

Bully Hayes

Bully Hayes

William Henry "Bully" Hayes has been described as a South Sea pirate and "the last of the Buccaneers", who together with Ben Pease, engaged in blackbirding in the 1860s and 1870s. Hayes operated across the breadth of the Pacific in the 1850s until his murder on 31 March 1877 by his cook Peter...

, an American ship captain who achieved notoriety for his activities in the Pacific in the 1850s to the 1870s, is described as arriving in Papeete

Papeete

-Sights:* Interactive Google map of Papeete, to discover the 30 major tourist attractions in Papeete downtown.*The waterfront esplanade*Bougainville Park -Sights:* Interactive Google map of Papeete, to discover the 30 major tourist attractions in Papeete downtown.*The waterfront...

, Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

in December 1868 on his ship Rona with 150 men from Niue

Niue

Niue , is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean. It is commonly known as the "Rock of Polynesia", and inhabitants of the island call it "the Rock" for short. Niue is northeast of New Zealand in a triangle between Tonga to the southwest, the Samoas to the northwest, and the Cook Islands to...

, who Hayes offering for sale as contract labourers. The expansion of plantations in Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

and Samoa

Samoa

Samoa , officially the Independent State of Samoa, formerly known as Western Samoa is a country encompassing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in...

also created destinations for blackbirders. The number of ships involved in the blackbirding trade resulted in the British Navy sending ships from the Australia Station

Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British—and later Australian—naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent.-History:In the early years following the establishment of the colony of New South Wales, ships based in Australian waters came under the control of the East Indies...

into the Pacific in order to suppress the trade. The activities of the ships of the Australian Squadron

Australian Squadron

The Australian Squadron was the name given to the British naval force assigned to the Australia Station from 1859 to 1911.The Squadron was initially a small force of Royal Navy warships based in Sydney, and although intended to protect the colonies of Australia and New Zealand, the ships were...

, (HMS Basilisk

HMS Basilisk (1848)

HMS Basilisk was a first-class paddle sloop of the Royal Navy, built at the Woolwich Dockyard and launched on 22 August 1848.-Propulsion trials:She participated in 1849 in trials in the English Channel with the screw sloop HMS Niger...

, HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle (1872)

HMS Beagle was a schooner of the Royal Navy, built by John Cuthbert, Millers Point, New South Wales and launched in December 1872.She commenced service on the Australia Station at Sydney in 1873 for anti-blackbirding operations in the South Pacific...

, HMS Conflict

HMS Conflict (1873)

HMS Conflict was a schooner of the Royal Navy, built by John Cuthbert, Millers Point, New South Wales and launched on 11 February 1873.-Royal Navy service:...

, HMS Renard

HMS Renard (1873)

HMS Renard was a schooner of the Royal Navy, built by John Cuthbert, Millers Point, New South Wales and launched 16 January 1873.She commenced service on the Australia Station at Sydney in 1873 for anti-blackbirding operations in the South Pacific and later hydrographic surveys around Fiji and the...

, HMS Sandfly

HMS Sandfly (1872)

HMS Sandfly was a schooner of the Royal Navy, built by John Cuthbert, Millers Point, New South Wales and launched on 5 December 1872. She commenced service on the Australia Station at Sydney in 1873 for anti-blackbirding operations in the South Pacific. She also undertook hydrographic surveys in...

& HMS Rosario

HMS Rosario (1860)

HMS Rosario was an 11-gun Rosario-class screw sloop of the Royal Navy, launched in 1860 at Deptford Dockyard. She served two commissions, including eight years on the Australia Station during which she fought to reduce illegal kidnappings of South Sea Islanders for the Queensland labour market. She...

), did not put an end to the blackbird trade, with the islands of Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

and Micronesia

Micronesia

Micronesia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising thousands of small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It is distinct from Melanesia to the south, and Polynesia to the east. The Philippines lie to the west, and Indonesia to the southwest....

also suffering the predations of blackbirders.

In Australia

From the 1860s the demand for labour in QueenslandQueensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, became the focus of blackbirding. Queensland was a self-governing British colony in northeastern Australia until 1901 when it became a state of the Commonwealth of Australia. Over a period of 40 years, from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, native non-European labourers for the sugar cane fields of Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

, were "recruited" from Vanuatu

Vanuatu

Vanuatu , officially the Republic of Vanuatu , is an island nation located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is some east of northern Australia, northeast of New Caledonia, west of Fiji, and southeast of the Solomon Islands, near New Guinea.Vanuatu was...

, Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

, the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state in Oceania, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly one thousand islands. It covers a land mass of . The capital, Honiara, is located on the island of Guadalcanal...

and the Loyalty Islands

Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands are an archipelago in the Pacific. They are part of the French territory of New Caledonia, whose mainland is away. They form the Loyalty Islands Province , one of the three provinces of New Caledonia...

of New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

as well as Niue

Niue

Niue , is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean. It is commonly known as the "Rock of Polynesia", and inhabitants of the island call it "the Rock" for short. Niue is northeast of New Zealand in a triangle between Tonga to the southwest, the Samoas to the northwest, and the Cook Islands to...

. The Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

government attempted to regulate the trade by requiring every ship engaged in recruiting labourers from the Pacific islands to carry a person approved by the government to ensure that labourers were willingly recruited and not kidnapped. However these government observers were not effective as they often corrupted by bonuses paid for labourers 'recruited' or blinded by alcohol and did nothing prevent sea-captains from tricking islanders on-board or otherwise engaging in kidnapping with violence.

The "recruitment" process almost always included an element of coercive recruitment (not unlike the press-gangs once employed by the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

in England) and indentured servitude

Indentured servant

Indentured servitude refers to the historical practice of contracting to work for a fixed period of time, typically three to seven years, in exchange for transportation, food, clothing, lodging and other necessities during the term of indenture. Usually the father made the arrangements and signed...

. Some 55,000 to 62,500 South Sea Islanders were taken to Australia.

These people were referred to as Kanakas (the French equivalent Canaques still applies to the ethnic Melanesians

Melanesians

Melanesians are an ethnic group in Melanesia. The original inhabitants of the group of islands now named Melanesia were likely the ancestors of the present-day Papuan-speaking people...

in New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

) and came from the Western Pacific

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

islands: from Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

, mainly the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, with a small number from the Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

n and Micronesia

Micronesia

Micronesia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising thousands of small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It is distinct from Melanesia to the south, and Polynesia to the east. The Philippines lie to the west, and Indonesia to the southwest....

n islands such as Tonga

Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga , is a state and an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, comprising 176 islands scattered over of ocean in the South Pacific...

(mainly 'Ata

'Ata

Ata is a small, rocky island in the far south of the Tonga archipelago, situated on . It is also known as Pylstaart island. It should not be confused with Atā, which is an uninhabited, low coral island in the string of small atolls along the Piha passage along the northside of Tongatapu, nor should...

), Samoa

Samoa

Samoa , officially the Independent State of Samoa, formerly known as Western Samoa is a country encompassing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in...

, Kiribati

Kiribati

Kiribati , officially the Republic of Kiribati, is an island nation located in the central tropical Pacific Ocean. The permanent population exceeds just over 100,000 , and is composed of 32 atolls and one raised coral island, dispersed over 3.5 million square kilometres, straddling the...

, Tuvalu

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

and Loyalty Islands

Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands are an archipelago in the Pacific. They are part of the French territory of New Caledonia, whose mainland is away. They form the Loyalty Islands Province , one of the three provinces of New Caledonia...

. Many of the workers were effectively slaves, but since the Slavery Abolition Act

Slavery Abolition Act

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 was an 1833 Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire...

made slavery illegal, they were officially called "indentured labourers" or the like. Some Australian Aboriginal people, especially from Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

, were also kidnapped and transported south to work on the farms.

The methods of blackbirding were varied. Some labourers were willing to be taken to Australia to work, while others were tricked or even forced. In some cases blackbirding ships (which made huge profits) would entice entire villages by luring them on board for trade or a religious service, and then setting sail. Many died during the voyage due to unsanitary conditions, and also in the fields due to the hard manual labour.

The question of how many Islanders were actually kidnapped or "blackbirded" is unknown and remains controversial. Official documents and accounts from the period often conflict with the oral tradition passed down to the descendants of workers. Stories of blatantly violent kidnapping tended to relate to the first 10–15 years of the trade. The majority of the 10,000 remaining in Australia in 1901 were repatriated between 1906-08 under the provisions of the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901

Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901

The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which was designed to facilitate the mass deportation of nearly all the Pacific Islanders working in Australia. Along with the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, enacted six days later, it formed an important part of the...

. A 1992 census of South Sea Islanders found there were around 10,000 descendants of the blackbirded labourers living in Queensland, although less than 3,500 were reported in the 2001 Australian census.

In Fiji

The blackbirding era began in FijiFiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

in 1865 when the first New Hebridean

New Hebrides

New Hebrides was the colonial name for an island group in the South Pacific that now forms the nation of Vanuatu. The New Hebrides were colonized by both the British and French in the 18th century shortly after Captain James Cook visited the islands...

and Solomon Island labourers arrived in Fiji to work on cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

plantations. Cotton had become scarce, and potentially an extremely profitable business, when the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

blocked most cotton exports from the southern United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. Since Fijian

Fijian people

Fijian people are the major indigenous people of the Fiji Islands, and live in an area informally called Melanesia. The Fijian people are believed to have arrived in Fiji from western Melanesia approximately 3,500 years ago, though the exact origins of the Fijian people are unknown...

s were not interested in regular sustained labour, the thousands of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an planters who flocked to Fiji sought labour from the Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

n islands. On 5 July 1865 Ben Pease

Ben Pease

Ben Pease or Benjamin Pease, was a notorious Blackbirder, engaged in recruiting and kidnapping Pacific islanders to provide labour for the plantations of Fiji....

received the first licence to provide 40 labourers from the New Hebrides

New Hebrides

New Hebrides was the colonial name for an island group in the South Pacific that now forms the nation of Vanuatu. The New Hebrides were colonized by both the British and French in the 18th century shortly after Captain James Cook visited the islands...

to Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

.

Attempts were made by the British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

and Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

Governments to regulate this transportation of labour. Melanesian labourers were to be recruited for three years, paid three pounds per year, issued with basic clothing and given access to the company store for supplies. Despite this, most Melanesians were recruited by deceit, usually being enticed abroad ships with gifts and then locked up. The living and working conditions in Fiji were even worse than those suffered by the later Indian

Demographics of India

The demographics of India are inclusive of the second most populous country in the world, with over 1.21 billion people , more than a sixth of the world's population. Already containing 17.5% of the world's population, India is projected to be the world's most populous country by 2025, surpassing...

indenture

Indenture

An indenture is a legal contract reflecting a debt or purchase obligation, specifically referring to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, an instrument used for commercial debt or real estate transaction.-Historical usage:An indenture is a...

d labourers. In 1875, the chief medical officer in Fiji, Sir William MacGregor

William MacGregor

Sir William MacGregor GCMG, CB was a Lieutenant-Governor of British New Guinea, Governor of Newfoundland and Governor of Queensland.-Early life:...

, listed a mortality rate of 540 out of every 1000 labourers. After the expiry of the three-year contract, the labourers were required to be transported back to their villages but most ship captains dropped them off at the first island they sighted off the Fiji waters. The British sent warships to enforce the law (Pacific Islanders' Protection Act of 1872) but only a small proportion of the culprits were prosecuted.

A notorious incident of the blackbirding trade was the 1871 voyage of the brig

Brig

A brig is a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. During the Age of Sail, brigs were seen as fast and manoeuvrable and were used as both naval warships and merchant vessels. They were especially popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries...

Carl, that was organised by Dr James Patrick Murray, to recruit labourers to work in the plantations of Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

. Murray had his men reverse their collars and carry black books, so to appear to be missionaries. When islanders were enticed to congregate Murray and his men would produce guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the voyage Murray shot about 60 islanders. He was never brought to trial for his actions as he was allowed to escape trial by giving evidence against crew members. The captain of the Carl, Joseph Armstrong, was later sentenced to death.

With the arrival of Indian indentured labourers

Indian indenture system

The Indian indenture system was an ongoing system of indenture by which thousands of Indians were transported to various colonies of European powers to provide labour for the plantations...

in Fiji from 1879, the number of Melanesian labourers decreased but they were still being recruited and employed, off the plantations in sugar mills and ports, until the start of the First World War. Most of the Melanesians recruited were males. After the recruitment ended, those who chose to stay in Fiji took Fijian wives and settled in areas around Suva

Suva

Suva features a tropical rainforest climate under the Koppen climate classification. The city sees a copious amount of precipitation during the course of the year. Suva averages 3,000 mm of precipitation annually with its driest month, July averaging 125 mm of rain per year. In fact,...

. Their descendants still remain a distinct community but their language and culture cannot be distinguished from native Fijians.

Descendants of Solomon Islanders living at Tamavua-i-Wai in Fiji received a High Court

High Court (Fiji)

The High Court of Fiji is one of three courts established by Chapter 9 of the Constitution of Fiji—the others being the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. The Constitution empowers Parliament to create other courts; these are subordinate to the High Court, which is authorized to oversee all...

verdict in their favour on 1 February 2007. The court refused a claim by the Seventh-day Adventist Church

Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is a Protestant Christian denomination distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the original seventh day of the Judeo-Christian week, as the Sabbath, and by its emphasis on the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ...

to force the islanders to vacate the land on which they had been living for seventy years.

Resistance

Blackbirding was associated with the death of Anglican missionary John Coleridge PattesonJohn Coleridge Patteson

John Coleridge Patteson was an Anglican bishop and martyr.Patteson was educated at The King's School, Ottery St Mary, Eton and then Balliol College, Oxford. He was ordained in 1853 in the Church of England...

on 20 September 1870. While the exact reasons for his death are unclear, it was linked at the time to resistance to blackbirding by local people, one of whom had been killed in a struggle with blackbirders and others abducted. Patteson, who wanted to take children away to be educated in a mission school, may have been perceived as a form of blackbirder. His death led to a crack-down on the abusive aspects of the practice.

Author Jack London

Jack London

John Griffith "Jack" London was an American author, journalist, and social activist. He was a pioneer in the then-burgeoning world of commercial magazine fiction and was one of the first fiction writers to obtain worldwide celebrity and a large fortune from his fiction alone...

wrote in his book The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark is a non-fictional, illustrated book by Jack London chronicling his sailing adventure in 1907 across the south Pacific in his ketch the Snark. Accompanying London on this voyage was his wife Charmian and a small crew...

that in 1907 at Langa Langa Lagoon

Langa Langa Lagoon

Langa Langa Lagoon or Akwalaafu is a natural lagoon on the West coast of Malaita near the provincial capital Auki within the Solomon Islands. The lagoon is 21 km in length and just under 1 km wide...

Malaita

Malaita

Malaita is the largest island of the Malaita Province in the Solomon Islands. A tropical and mountainous island, Malaita's pristine river systems and tropical forests have not been exploited. Malaita is the most populous island of the Solomon Islands, with 140,000 people or more than a third of the...

, Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state in Oceania, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly one thousand islands. It covers a land mass of . The capital, Honiara, is located on the island of Guadalcanal...

a "recruiting" ship encountered resistance to the attempted "kidnapping":

"..still bore the tomahawk marks where the Malaitans at Langa Langa several months before broke in for the trove of rifles and ammunition locked therein, after bloodily slaughtering Jansen's predecessor, Captain Mackenzie. The burning of the vessel was somehow prevented by the black crew, but this was so unprecedented that the owner feared some complicity between them and the attacking party. However, it could not be proved, and we sailed with the majority of this same crew. The present skipper smilingly warned us that the same tribe still required two more heads from the Minota, to square up for deaths on the Ysabel plantation. (p 387)

"Three fruitless days were spent at Su'u. The Minota got no recruits from the bush and the bushmen got no heads from the Minota. We towed out with a whaleboat and ran along the coast to Langa Langa, a large village of salt-water people built with labour on a sand bank - literally built up"

See also

- SlaverySlaverySlavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

- South Sea IslanderSouth Sea IslanderThe Australian label South Sea Islanders refers to the Australian descendants of people from the more than 80 islands in the Western Pacific including the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in Melanesia and the Loyalty Islands, Samoa, Kiribati, Rotuma and Tuvalu in Polynesia and Micronesia who were...

- Coolies

- Mal MeningaMal MeningaMalcolm Norman Meninga AM is an Australian former rugby league test captain and current coach of Queensland's State of Origin team. As a player he was a legendary goal-kicking centre, counted amongst the finest footballers of the 20th century...

- KanakasKanakasKanaka was the term for a worker from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia , Fiji and Queensland in the 19th and early 20th centuries...

- ShanghaiingShanghaiingShanghaiing refers to the practice of conscripting men as sailors by coercive techniques such as trickery, intimidation, or violence. Those engaged in this form of kidnapping were known as crimps. Until 1915, unfree labor was widely used aboard American merchant ships...

- ImpressmentImpressmentImpressment, colloquially, "the Press", was the act of taking men into a navy by force and without notice. It was used by the Royal Navy, beginning in 1664 and during the 18th and early 19th centuries, in wartime, as a means of crewing warships, although legal sanction for the practice goes back to...

, the formal term for pressganging - Bully HayesBully HayesWilliam Henry "Bully" Hayes has been described as a South Sea pirate and "the last of the Buccaneers", who together with Ben Pease, engaged in blackbirding in the 1860s and 1870s. Hayes operated across the breadth of the Pacific in the 1850s until his murder on 31 March 1877 by his cook Peter...

- Ben PeaseBen PeaseBen Pease or Benjamin Pease, was a notorious Blackbirder, engaged in recruiting and kidnapping Pacific islanders to provide labour for the plantations of Fiji....

External links

- Background and history of the South Sea Islanders - Queensland Department of Premier and Cabinet

- http://www.janeresture.com/kanakas/index.htm Jane Resture, The Kanakas and the Cane Fields