Cephalopod

Encyclopedia

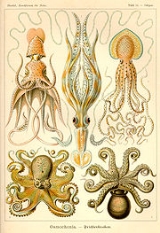

A cephalopod is any member of the mollusc

an class

Cephalopoda (Greek

plural (kephalópoda); "head-feet"). These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arm

s or tentacle

s (muscular hydrostat

s) modified from the primitive molluscan foot. Fishermen sometimes call them inkfish, referring to their common ability to squirt ink

. The study of cephalopods is a branch of malacology

known as teuthology.

Cephalopods became dominant during the Ordovician

period, represented by primitive nautiloids. The class now contains two, only distantly related, extant subclasses: Coleoidea

, which includes octopus

es, squid

, and cuttlefish

; and Nautiloidea, represented by Nautilus

and Allonautilus

. In the Coleoidea, the molluscan shell has been internalized or is absent, whereas in the Nautiloidea, the external shell remains. About 800 living species

of cephalopods have been identified. Two important extinct taxa

are the Ammonoidea (ammonites) and Belemnoidea

(belemnites).

have been described, although the soft-bodied nature of cephalopods means they are not easily fossilised.

Cephalopods are found in all the oceans of Earth. None of them can tolerate freshwater

, but the brief squid, Lolliguncula brevis

, found in Chesapeake Bay

, may be a notable exception in that it tolerates brackish water

.

Cephalopods occupy most of the depth of the ocean, from the abyssal plane to the sea surface. Their diversity is greatest near the equator (~40 species retrieved in nets at 11°N by a diversity study) and decreases towards the poles (~5 species captured at 60°N).

s, and have well developed senses and large brain

s (larger than those of gastropods). The nervous system

of cephalopods is the most complex of the invertebrates and their brain-to-body-mass ratio falls between that of warm- and cold-blooded vertebrates. The brain is protected in a cartilaginous

cranium. The giant nerve

fibers of the cephalopod mantle

have been widely used as experimental material in neurophysiology

for many years; their large diameter (due to lack of myelination) makes them relatively easy to study.

Cephalopods are social creatures; when isolated from their own kind, they will take to shoaling

with fish.

Some cephalopods are able to fly through air for distances up to 50 m. While the organisms are not particularly aerodynamic, they achieve these rather impressive ranges by use of jet-propulsion; water continues to be expelled from the funnel while the organism is in flight.

s, and have a variety of chemical sense organs. Octopuses use their tentacles to explore their environment and can use them for depth perception.

.jpg)

can distinguish the brightness, size, shape, and horizontal or vertical orientation of objects. The morphological construction gives cephalopod eyes the same performance as sharks'; however, their construction differs, as cephalopods lack a cornea, and have an everted retina. Cephalopods' eyes are also sensitive to the plane of polarization of light. Surprisingly—given their ability to change color—all octopuses and most cephalopods are color blind. When camouflaging themselves, they use their chromatophores to change brightness and pattern according to the background they see, but their ability to match the specific color of a background may come from cells such as iridophores and leucophores that reflect light from the environment. They also produce visual pigments throughout their body, and may sense light levels directly from their body. Evidence of color vision

has been found in the sparkling enope squid (Watasenia scintillans), which achieves color vision by the use of three distinct retinal

molecules (A1, sensitive to red; A2, to purple, and A4, to yellow?) which bind to its opsin

.

Unlike many other cephalopods, nautilus

es do not have good vision; their eye structure is highly developed, but lacks a solid lens

. They have a simple "pinhole

" eye through which water can pass. Instead of vision, the animal is thought to use olfaction

as the primary sense for foraging

, as well as locating or identifying potential mates.

Most cephalopods possess chromatophore

Most cephalopods possess chromatophore

s - that is, coloured pigments - which they can use in a startling array of fashions. As well as providing camouflage with their background, some cephalopods bioluminesce, shining light downwards to disguise their shadows from any predators that may lurk below. The bioluminescence is produced by bacterial symbionts; the host cephalopod is able to detect the light produced by these organisms. Bioluminescence

may also be used to entice prey, and some species use colourful displays to impress mates, startle predators, or even communicate with one another. It is not certain whether bioluminescence is actually of epithelial origin or if it is a bacterial production.

Evidence of original colouration has been detected in cephalopod fossils dating as far back as the Silurian

; these orthoconic individuals bore concentric stripes, which are thought to have served as camouflage. Devonian cephalopods bear more complex colour patterns, whose function may be more complex.

belonging to the suborder

Cirrina, all known cephalopods have an ink sac, which can be used to expel a cloud of dark ink to confuse predators. This sac is a muscular bag which originated as an extension of the hind gut. It lies beneath the gut and opens into the anus, into which its contents – almost pure melanin

– can be squirted; its proximity to the base of the funnel means the ink can be distributed by ejected water as the cephalopod uses its jet propulsion. The ejected cloud of melanin is usually mixed, upon expulsion, with mucus

, produced elsewhere in the mantle, and therefore forms a thick cloud, resulting in visual (and possibly chemosensory) impairment of the predator, like a smokescreen. However, a more sophisticated behaviour has been observed, in which the cephalopod releases a cloud, with a greater mucus content, that approximately resembles the cephalopod that released it (this decoy is referred to as a Pseudomorph). This strategy often results in the predator attacking the pseudomorph, rather than its rapidly departing prey. For more information, see Inking behaviors.

The inking behaviour of cephalopods has led to a common name of "inkfish", primarily used in fisheries science and the fishing industry

, paralleling the terms white fish

, oily fish

, and shellfish

.

s (also known as branchial heart

s) that move blood through the capillaries of the gill

s. A single systemic heart then pumps the oxygenated blood through the rest of the body.

Like most molluscs, cephalopods use hemocyanin

, a copper-containing protein, rather than hemoglobin

, to transport oxygen. As a result, their blood is colorless when deoxygenated and turns blue when exposed to air.

There is a trade-off with gill size regarding lifestyle. To achieve fast speeds, gills need to be small - water will be passed through them quickly when energy is needed, compensating for their small size. However, organisms which spend most of their time moving slowly along the bottom do not naturally pass much water through their cavity for locomotion; thus they have larger gills, along with complex systems to ensure that water is constantly washing through their gills, even when the organism is stationary. The water flow is controlled by contractions of the radial and circular mantle cavity muscles.

The gills of cephalopods are supported by a skeleton of robust fibrous proteins; the lack of mucopolysaccharides distinguishes this matrix from cartilage. The gills are also thought to be involved in excretion, with NH4+ being swapped with K+ from the seawater.

Whilst jet propulsion is never the sole mode of locomotion, the stop-start motion provided by the jets continues to be useful for providing bursts of high speed - not least when capturing prey or avoiding predators. Indeed, it makes cephalopods the fastest marine invertebrates,

and they can out-accelerate most fish.

The jet is supplemented with fin motion; in the squid, the fins flap each time that a jet is released, amplifying the thrust; they are then extended between jets (presumably to avoid sinking).

Oxygenated water is taken into the mantle cavity

to the gill

s and through muscular contraction of this cavity, the spent water is expelled through the hyponome

, created by a fold in the mantle. The size difference between the posterior and anterior ends of this organ control the speed of the jet the organism can produce. The velocity of the organism can be accurately predicted for a given mass and morhpology of animal. Motion of the cephalopods is usually backward as water is forced out anteriorly through the hyponome, but direction can be controlled somewhat by pointing it in different directions. Some cephalopods accompany this expulsion of water with a gunshot-like popping noise, thought to function to frighten away potential predators.

Cephalopods employ a similar method of propulsion despite their increasing size (as they grow) changing the dynamics of the water in which they find themselves. Thus their paralarvae do not extensively use their fins (which are less efficient at low Reynolds numbers) and primarily use their jets to propel themselves upwards, whereas large adult cephalopods tend to swim less efficiently and with more reliance on their fins.

Early cephalopods are thought to have produced jets by drawing their body into their shells, as Nautilus does today. Nautilus is also capable of creating a jet by undulations of its funnel; this slower flow of water is more suited to the extraction of oxygen from the water. The jet velocity in Nautilus is much slower than in coleoids, but less musculature and energy is involved in its production. Jet thrust in cephalopods is controlled primarily by the maximum diameter of the funnel orifice (or, perhaps, the average diameter of the funnel) and the diameter of the mantle cavity. Changes in the size of the orifice are used most at intermediate velocities. The absolute velocity achieved is limited by the cephalopod's requirement to inhale water for expulsion; this intake limits the maximum velocity to eight body-lengths per second, a speed which most cephalopods can attain after two funnel-blows. Water refills the cavity by entering not only through the orifices, but also though the funnel. Squid can expel up to 94% of the fluid within their cavity in a single jet thrust. To accommodate the rapid changes in water intake and expulsion, the orifices are highly flexible and can change their size by a factor of twenty; the funnel radius, conversely, changes only by a factor of around 1.5.

Early cephalopods are thought to have produced jets by drawing their body into their shells, as Nautilus does today. Nautilus is also capable of creating a jet by undulations of its funnel; this slower flow of water is more suited to the extraction of oxygen from the water. The jet velocity in Nautilus is much slower than in coleoids, but less musculature and energy is involved in its production. Jet thrust in cephalopods is controlled primarily by the maximum diameter of the funnel orifice (or, perhaps, the average diameter of the funnel) and the diameter of the mantle cavity. Changes in the size of the orifice are used most at intermediate velocities. The absolute velocity achieved is limited by the cephalopod's requirement to inhale water for expulsion; this intake limits the maximum velocity to eight body-lengths per second, a speed which most cephalopods can attain after two funnel-blows. Water refills the cavity by entering not only through the orifices, but also though the funnel. Squid can expel up to 94% of the fluid within their cavity in a single jet thrust. To accommodate the rapid changes in water intake and expulsion, the orifices are highly flexible and can change their size by a factor of twenty; the funnel radius, conversely, changes only by a factor of around 1.5.

Some octopus species are also able to walk along the sea bed. Squids and cuttlefish can move short distances in any direction by rippling of a flap of muscle

around the mantle.

While most cephalopods float (i.e. are neutrally buoyant

or nearly so; in fact most cephalopods are about 2-3% denser than seawater), they achieve this in different ways.

Some, such as Nautilus

, allow gas to diffuse into the gap between the mantle and the shell; others allow purer water to ooze from their kidneys, forcing out denser salt water from the body cavity; others, like some fish, accumulate oils in the liver; and some octopuses have a gelatinous body with lighter chlorine

ion

s replacing sulfate

in the body chemistry.

es are the only extant cephalopods with an external shell. However, all molluscan shells are formed from the ectoderm (outer layer of the embryo); in cuttlefish

(Sepia spp.), for example, an invagination of the ectoderm forms during the embryonic period, resulting in a shell that is internal in the adult. The same is true of the chitinous gladius of squid and octopus. Cirrate octopus

es have cartilaginous fin supports, which are sometimes referred to as a "shell vestige" or "gladius". The Incirrina have no vestige of an internal shell, and some squid also lack a gladius. Interestingly, the shelled coleoids do not form a clade or even a paraphyletic group. The Spirula shell begins as an organic structure, and is then very rapidly mineralized. Shells that are "lost" may be lost by resorption of the calcium carbonate component.

Females of the octopus genus Argonauta secrete a specialised paper-thin eggcase in which they reside, and this is popularly regarded as a "shell", although it is not attached to the body of the animal.

The largest group of shelled cephalopods, the ammonite

s, are extinct, but their shells are very common as fossil

s.

The deposition of carbonate, leading to a mineralized shell, appears to be related to the acidity of the organic shell matrix (see Mollusc shell

); shell-forming cephalopods have an acidic matrix, whereas the gladius of squid has a basic matrix.

they number eight or ten. Decapods such as cuttlefish and squid have five pairs. The longer two, termed tentacle

s, are actively involved in capturing prey; they can lengthen rapidly (in as little as 15 milliseconds). In giant squid

they may reach a length of 8 metres. They may terminate in a broadened, sucker-coated club. The shorter four pairs are termed arms

, and are involved in holding and manipulating the captured organism. They too have suckers, on the side closest to the mouth; these help to hold onto the prey. Octopods only have four pairs of sucker-coated arms, as the name suggests.

The tentacle consists of a thick central nerve cord (which must be thick to allow each sucker to be controlled independently) surrounded by circular and radial muscles. Because the volume of the tentacle remains constant, contracting the circular muscles decreases the radius and permits the rapid increase in length. Typically a 70% lengthening is achieved by decreasing the width by 23%. The shorter arms lack this capability.

The size of the tentacle is related to the size of the buccal cavity; larger, stronger tentacles can hold prey as small bites are taken from it; with more numerous, smaller tentacles, prey is swallowed whole, so the mouth cavity must be larger.

Externally shelled nautilids (Nautilus

and Allonautilus

) have on the order of 90 finger-like appendages, termed tentacles, which lack suckers but are sticky instead, and are partly retractable.

, although it is reduced in most octopus and absent altogether in Spirula. They feed by capturing prey with their tentacles, drawing it in to their mouth and taking bites from it. They have a mixture of toxic digestive juices, some of which are manufactured by symbiotic algae, which they eject from their salivary glands onto their captured prey held in their mouth. These juices separate the flesh of their prey from the bone or shell. The salivary gland has a small tooth at its end which can be poked into an organism to digest it from within.

The digestive gland itself is rather short. It has four elements, with food passing through the crop, stomach and caecum before entering the intestine. Most digestion, as well as the absorption of nutrients, occurs in the digestive gland, sometimes called the liver. Nutrients and waste materials are exchanged between the gut and the digestive gland through a pair of connections linking the gland to the junction of the stomach and caecum. Cells in the digestive gland directly release pigmented excretory chemicals into the lumen of the gut, which are then bound with mucus passed through the anus as long dark strings, ejected with the aid of exhaled water from the funnel. Cephalopods tend to concentrate ingested heavy metals in their body tissue.

Cephalopod radulae are known from fossil deposits dating back to the Ordovician. They are usually preserved within the cephalopod's body chamber, commonly in conjunction with the mandibles; but this need not always be the case; many radulae are preserved in a range of settings in the Mason Creek.

Radulae are usually difficult to detect, even when they are preserved in fossils, as the rock must weather and crack in exactly the right fashion to expose them; for instance, radulae have only been found in nine of the 43 ammonite genera, and they are rarer still in non-ammonoid forms: only three pre-Mesozoic species possess one.

. Filtered nitrogenous waste is produced in the pericardial

cavity of the branchial heart

s, each of which is connected to a nephridium by a narrow canal. The canal delivers the excreta to a bladder-like renal sac, and also resorbs excess water from the filtrate. Several outgrowths of the lateral vena cava project into the renal sac, continuously inflating and deflating as the branchial hearts beat. This action helps to pump the secreted waste into the sacs, to be released into the mantle cavity through a pore.

Nautilus, unusually, possesses four nephridia, none of which are connected to the pericardial cavities.

is thought to be important in shell formation in terrestrial molluscs, and in other nonmolluscan lineages.

Because protein

(i.e. flesh) is a major constituent of the cephalopod diet, large amounts of ammonium

are produced as waste. The main organs involved with the release of this excess ammonium are the gills.

The rate of this release is the lowest in the shelled cephalopods Nautilus

and Sepia

, probably as a result of their use of nitrogen

to fill their shells with gas to produce buoyancy. Other cephalopods use ammonium in a similar way, storing the ion

s (as ammonium chloride

) themselves to reduce their overall density and thus become more buoyant.

. That, in turn, is used to transfer the spermatophores to the female. In species where the hectocotylus is missing, the penis is long and able to extend beyond the mantle cavity and transfers the spermatophores directly to the female. Deep water squid have the greatest known penis length relative to body size of all mobile animals, second in the entire animal kingdom only to certain sessile barnacle

s. Penis elongation in Onykia ingens may result in a penis that is as long as the mantle, head and arms combined.

Most cephalopods tend towards a semelparous reproduction strategy; they lay many small eggs in one batch and die afterwards. The Nautiloidea, on the other hand, stick to iteroparity; they produce a few large eggs in each batch and live for a long time.

External sexual characteristics are lacking in cephalopods, so cephalopods use colour communication. A courting male will approach a likely looking opposite number flashing his brightest colours, often in rippling displays. If the other cephalopod is female and receptive, her skin will change colour to become pale, and mating will occur. If the other cephalopod remains brightly coloured, it is taken as a warning.

The male has a sperm-carrying arm, known as the hectocotylous arm, with which to impregnate the female. In many cephalopods, mating occurs head to head and the male may simply transfer sperm to the female. Others may detach the sperm-carrying arm and leave it attached to the female. In the paper nautilus, this arm remains active and wriggling for some time, prompting the zoologists who discovered it to conclude it was some sort of worm-like parasite. It was duly given a genus name Hectocotylus, which held for some time until the mistake was discovered.

Nidamental gland

s are involved in the secretion of egg cases or the gelatinous substance comprising egg masses. The eggs may be brooded: female paper nautilus construct a shelter for the young, while Gonatiid squid carry a larva-laden membrane from the hooks on their arms. Other cephalopods deposit their young under rocks and aerate them with their tentacles hatching. Often, though, the eggs are left to their own devices; many squid lay sausage-like bunches of eggs in crevices or occasionally on the sea floor. Cuttlefish

lay their eggs separately in cases and attach them to coral or algal fronds. Fossilised egg clutches show that ammonites also laid clutches of eggs.

Cephalopods are occasionally long-lived, especially in the deep water or polar forms, but most of the group live fast and die young, maturing rapidly to their adult size. Some may gain as much as 12% of their body mass each day. Most live for one to two years, reproducing and then dying shortly thereafter.

To free up resources for reproduction, many squid are known to resorb the muscle tissue of their mantle and tentacles, breaking down the tissue and using the energy contained therein to produce more gametes.

l stage. The fertilised ovum

initially divides to produce a disc of germinal cells at one pole, with the yolk remaining at the opposite pole. The germinal disc grows to envelop and eventually absorb the yolk, forming the embryo. The tentacles and arms first appear at the hind part of the body, where the foot would be in other molluscs, and only later migrate towards the head.

The funnel of cephalopods develops on the top of their head, whereas the mouth develops on the opposite surface. The early embryological stages are reminiscent of ancestral gastropods and extant Monoplacophora

.

The shells develop from the ectoderm as an organic framework which is subsequently mineralised. In Sepia, which has an internal shell, the ectoderm forms an invagination whose pore is sealed off before this organic framework is deposited.

The gene engrailed

is expressed first in the arms, funnel and optic vesicles, and is only later present in the tentacles and eyelids. It is expressed in embryonic stages 17–19 in all arm buds, and subsequently in the future-tentacles in stages 24–5, suggesting that it may serve a role in the differential development of tentacles. Sequential expression of Hox genes is also observed in cephalopod arms.

The process from spawning to hatching follows a similar trajectory in all species, the main variable being the amount of yolk available to the young and when it is absorbed by the embryo.

Young do not pass through a larval stage, strictly speaking. They quickly learn how to hunt, using encounters with prey to refine their strategies.

Growth in juveniles is usually allometric, whilst adult growth is isometric.

to some gastropods was used in support of this view. The development of a siphuncle

would have allowed the shells of these early forms to become gas-filled (thus buoyant) in order to support them and keep the shells upright while the animal crawled along the floor, and separated the true cephalopods from putative ancestors such as Knightoconus

, which lacked a siphuncle. Neutral or positive buoyancy (i.e. the ability to float) would have come later, followed by swimming in the Plectronocerida

and eventually jet propulsion in more derived cephalopods.

However, some morphological evidence is difficult to reconcile with this view, and the redescription of Nectocaris pteryx

, which did not have a shell and appeared to possess jet propulsion in the manner of "derived" cephalopods, complicated the question of the order in which cephalopod features developed – provided Nectocaris is a cephalopod at all. Their position within the Mollusca is currently wide open to interpretation - see Mollusca#Phylogeny.

Early cephalopods were likely predators near the top of the food chain. They underwent pulses of diversification during the Ordovician period to become diverse and dominant in the Paleozoic

and Mesozoic

seas.

In the Early Palaeozoic, their range was far more restricted than today; they were mainly constrained to sublittoral regions of shallow shelves of the low latitudes, and usually occur in association with thrombolites. A more pelagic habit was gradually adopted as the Ordovician progressed. Deep-water cephalopods, whilst rare, have been found in the Lower Ordovician - but only in high-latitude waters.

The mid Ordovician saw the first cephalopods with septa strong enough to cope with the pressures associated with deeper water, and could inhabit depths greater than 100–200 m. The direction of shell coiling would prove to be crucial to the future success of the lineages; endogastric coiling would only permit large size to be attained with a straight shell, whereas exogastric coiling - initially rather rare - permitted the spirals familiar from the fossil record to develop, with their corresponding large size and diversity. (Endogastric mean the shell is curved so as the ventral or lower side is longitudinally concave (belly in); exogastric means the shell is curved so as the ventral side is longitudinally convex (belly out) allowing the funnel to be pointed backwards beneath the shell.)

The ancestors of coleoids (including most modern cephalopods) and the ancestors of the modern nautilus, had diverged by the Floian Age of the Early Ordovician Period, over 470 million years ago. The Bactritida

The ancestors of coleoids (including most modern cephalopods) and the ancestors of the modern nautilus, had diverged by the Floian Age of the Early Ordovician Period, over 470 million years ago. The Bactritida

, a Silurian–Triassic group of orthocones, are widely held to be paraphyletic to the coleoids and ammonoids – that is, the latter groups arose from within the Bactritida. An increase in the diversity of the coleoids and ammonoids is observed around the start of the Devonian period, and corresponds with a profound increase in fish diversity. This could represent the origin of the two derived groups.

Unlike most modern cephalopods, most ancient varieties had protective shells. These shells at first were conical but later developed into curved nautiloid shapes seen in modern nautilus

species.

Competitive pressure from fish is thought to have forced the shelled forms into deeper water, which provided an evolutionary pressure towards shell loss and gave rise to the modern coleoids, a change which led to greater metabolic costs associated with the loss of buoyancy, but which allowed them to recolonise shallow waters. However, some of the straight-shelled nautiloids evolved into belemnites, out of which some evolved into squid

and cuttlefish

. The loss of the shell may also have resulted from evolutionary pressure to increase manoeuvrability, resulting in a more fish-like habit.

Molecular estimates for clade divergence vary. One 'statistically robust' estimate has Nautilus diverging from Octopus at .

The classification presented here, for recent cephalopods, follows largely from Current Classification of Recent Cephalopoda (May 2001), for fossil cephalopods takes from Arkell et al. 1957, Teichert and Moore 1964, Teichert 1988, and others. The three subclasses are traditional, corresponding to the three orders of cephalopods recognized by Bather.

The classification presented here, for recent cephalopods, follows largely from Current Classification of Recent Cephalopoda (May 2001), for fossil cephalopods takes from Arkell et al. 1957, Teichert and Moore 1964, Teichert 1988, and others. The three subclasses are traditional, corresponding to the three orders of cephalopods recognized by Bather.

Class Cephalopoda († indicates extinct groups)

Other classifications differ, primarily in how the various decapod

orders are related, and whether they should be orders or families.

Nautiloids in general, (Teichert and Moore 1964) Sequence as given.

Paleozoic Ammonoidea ( Miller, Furnish, and Schindewolf, 1957)

Mesozoic Ammonoidea (Arkel et al., 1957)

Subsequent revisions include the establishment of three Upper Cambrian orders, the Plectronocerida, Protactinocerida and Yanhecerida; separation of the pseudorthocerids as the Pseudorthocerida, and elevating orthoceritoids as the Subclass Orthoceratoidea.

Class Cephalopoda

Class Cephalopoda

Another recent system divides all cephalopods into two clade

Another recent system divides all cephalopods into two clade

s. One includes nautilus and most fossil nautiloids. The other clade (Neocephalopoda

or Angusteradulata) is closer to modern coleoids, and includes belemnoids, ammonoids, and many orthocerid families. There are also stem group cephalopods of the traditional Ellesmerocerida

that belong to neither clade.

Mollusca

The Mollusca , common name molluscs or mollusksSpelled mollusks in the USA, see reasons given in Rosenberg's ; for the spelling mollusc see the reasons given by , is a large phylum of invertebrate animals. There are around 85,000 recognized extant species of molluscs. Mollusca is the largest...

an class

Taxonomic rank

In biological classification, rank is the level in a taxonomic hierarchy. Examples of taxonomic ranks are species, genus, family, and class. Each rank subsumes under it a number of less general categories...

Cephalopoda (Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

plural (kephalópoda); "head-feet"). These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arm

Cephalopod arm

A cephalopod arm is distinct from a tentacle, though the terms are often used interchangeably.Generally, cephalopod arms have suckers along most of their length, as opposed to tentacles, which have suckers only near their ends. Octopuses have eight arms and no tentacles, while squid and cuttlefish...

s or tentacle

Tentacle

A tentacle or bothrium is one of usually two or more elongated flexible organs present in animals, especially invertebrates. The term may also refer to the hairs of the leaves of some insectivorous plants. Usually, tentacles are used for feeding, feeling and grasping. Anatomically, they work like...

s (muscular hydrostat

Muscular hydrostat

A muscular hydrostat is a biological structure found in animals. It is used to manipulate items or to move its host about and consists mainly of muscles with no skeletal support...

s) modified from the primitive molluscan foot. Fishermen sometimes call them inkfish, referring to their common ability to squirt ink

Cephalopod ink

Cephalopod ink is a dark pigment released into water by most species of cephalopod, usually as an escape mechanism. All cephalopods, with the exception of the Nautilidae and the species of octopus belonging to the suborder Cirrina, are able to release ink....

. The study of cephalopods is a branch of malacology

Malacology

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology which deals with the study of the Mollusca , the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, octopus and squid, and numerous other kinds, many of which have shells...

known as teuthology.

Cephalopods became dominant during the Ordovician

Ordovician

The Ordovician is a geologic period and system, the second of six of the Paleozoic Era, and covers the time between 488.3±1.7 to 443.7±1.5 million years ago . It follows the Cambrian Period and is followed by the Silurian Period...

period, represented by primitive nautiloids. The class now contains two, only distantly related, extant subclasses: Coleoidea

Coleoidea

Subclass Coleoidea, or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the primarily soft-bodied creatures. Unlike its sister group Nautiloidea, whose members have a rigid outer shell for protection, the coleoids have at most an internal bone or shell that is used for buoyancy or support...

, which includes octopus

Octopus

The octopus is a cephalopod mollusc of the order Octopoda. Octopuses have two eyes and four pairs of arms, and like other cephalopods they are bilaterally symmetric. An octopus has a hard beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms...

es, squid

Squid

Squid are cephalopods of the order Teuthida, which comprises around 300 species. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, a mantle, and arms. Squid, like cuttlefish, have eight arms arranged in pairs and two, usually longer, tentacles...

, and cuttlefish

Cuttlefish

Cuttlefish are marine animals of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda . Despite their name, cuttlefish are not fish but molluscs....

; and Nautiloidea, represented by Nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

and Allonautilus

Allonautilus

The genus Allonautilus contains two species of nautiluses, which differ significantly in terms of morphology from those placed in the sister taxon Nautilus. Allonautilus is now thought to be a descendant of Nautilus and the latter paraphyletic.-External links:*...

. In the Coleoidea, the molluscan shell has been internalized or is absent, whereas in the Nautiloidea, the external shell remains. About 800 living species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of cephalopods have been identified. Two important extinct taxa

Taxon

|thumb|270px|[[African elephants]] form a widely-accepted taxon, the [[genus]] LoxodontaA taxon is a group of organisms, which a taxonomist adjudges to be a unit. Usually a taxon is given a name and a rank, although neither is a requirement...

are the Ammonoidea (ammonites) and Belemnoidea

Belemnoidea

Belemnoids are an extinct group of marine cephalopod, very similar in many ways to the modern squid and closely related to the modern cuttlefish. Like them, the belemnoids possessed an ink sac, but, unlike the squid, they possessed ten arms of roughly equal length, and no tentacles...

(belemnites).

Distribution

There are around 800 species of cephalopod, although new species continue to be described. An estimated 11,000 extinct taxaTaxon

|thumb|270px|[[African elephants]] form a widely-accepted taxon, the [[genus]] LoxodontaA taxon is a group of organisms, which a taxonomist adjudges to be a unit. Usually a taxon is given a name and a rank, although neither is a requirement...

have been described, although the soft-bodied nature of cephalopods means they are not easily fossilised.

Cephalopods are found in all the oceans of Earth. None of them can tolerate freshwater

Freshwater

Fresh water is naturally occurring water on the Earth's surface in ice sheets, ice caps, glaciers, bogs, ponds, lakes, rivers and streams, and underground as groundwater in aquifers and underground streams. Fresh water is generally characterized by having low concentrations of dissolved salts and...

, but the brief squid, Lolliguncula brevis

Lolliguncula brevis

Lolliguncula brevis, or the Atlantic brief squid, is a small species of squid in the Loliginidae family. It is found in shallow parts of the western Atlantic Ocean.-Distribution:...

, found in Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

, may be a notable exception in that it tolerates brackish water

Brackish water

Brackish water is water that has more salinity than fresh water, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing of seawater with fresh water, as in estuaries, or it may occur in brackish fossil aquifers. The word comes from the Middle Dutch root "brak," meaning "salty"...

.

Cephalopods occupy most of the depth of the ocean, from the abyssal plane to the sea surface. Their diversity is greatest near the equator (~40 species retrieved in nets at 11°N by a diversity study) and decreases towards the poles (~5 species captured at 60°N).

Nervous system and behaviour

Cephalopods are widely regarded as the most intelligent of the invertebrateInvertebrate

An invertebrate is an animal without a backbone. The group includes 97% of all animal species – all animals except those in the chordate subphylum Vertebrata .Invertebrates form a paraphyletic group...

s, and have well developed senses and large brain

Brain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

s (larger than those of gastropods). The nervous system

Nervous system

The nervous system is an organ system containing a network of specialized cells called neurons that coordinate the actions of an animal and transmit signals between different parts of its body. In most animals the nervous system consists of two parts, central and peripheral. The central nervous...

of cephalopods is the most complex of the invertebrates and their brain-to-body-mass ratio falls between that of warm- and cold-blooded vertebrates. The brain is protected in a cartilaginous

Cartilage

Cartilage is a flexible connective tissue found in many areas in the bodies of humans and other animals, including the joints between bones, the rib cage, the ear, the nose, the elbow, the knee, the ankle, the bronchial tubes and the intervertebral discs...

cranium. The giant nerve

Nerve

A peripheral nerve, or simply nerve, is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of peripheral axons . A nerve provides a common pathway for the electrochemical nerve impulses that are transmitted along each of the axons. Nerves are found only in the peripheral nervous system...

fibers of the cephalopod mantle

Mantle (mollusc)

The mantle is a significant part of the anatomy of molluscs: it is the dorsal body wall which covers the visceral mass and usually protrudes in the form of flaps well beyond the visceral mass itself.In many, but by no means all, species of molluscs, the epidermis of the mantle secretes...

have been widely used as experimental material in neurophysiology

Neurophysiology

Neurophysiology is a part of physiology. Neurophysiology is the study of nervous system function...

for many years; their large diameter (due to lack of myelination) makes them relatively easy to study.

Cephalopods are social creatures; when isolated from their own kind, they will take to shoaling

Shoaling and schooling

In biology, any group of fish that stay together for social reasons are said to be shoaling , and if, in addition, the group is swimming in the same direction in a coordinated manner, they are said to be schooling . In common usage, the terms are sometimes used rather loosely...

with fish.

Some cephalopods are able to fly through air for distances up to 50 m. While the organisms are not particularly aerodynamic, they achieve these rather impressive ranges by use of jet-propulsion; water continues to be expelled from the funnel while the organism is in flight.

Senses

Cephalopods have advanced vision, can detect gravity with statocystStatocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in Xenoturbella. The statocyst consists of a sac-like structure containing a mineralised mass and numerous...

s, and have a variety of chemical sense organs. Octopuses use their tentacles to explore their environment and can use them for depth perception.

.jpg)

Vision

Most cephalopods rely on vision to detect predators and prey, and to communicate with one another. Consequently, cephalopod vision is acute: training experiments have shown that the common octopusCommon Octopus

The Common Octopus is the most studied of all octopus species. Its natural range extends from the Mediterranean Sea and the southern coast of England to at least Senegal in Africa. It also occurs off the Azores, Canary Islands, and Cape Verde Islands.- Characteristics :O. vulgaris grows to 25 cm...

can distinguish the brightness, size, shape, and horizontal or vertical orientation of objects. The morphological construction gives cephalopod eyes the same performance as sharks'; however, their construction differs, as cephalopods lack a cornea, and have an everted retina. Cephalopods' eyes are also sensitive to the plane of polarization of light. Surprisingly—given their ability to change color—all octopuses and most cephalopods are color blind. When camouflaging themselves, they use their chromatophores to change brightness and pattern according to the background they see, but their ability to match the specific color of a background may come from cells such as iridophores and leucophores that reflect light from the environment. They also produce visual pigments throughout their body, and may sense light levels directly from their body. Evidence of color vision

Color vision

Color vision is the capacity of an organism or machine to distinguish objects based on the wavelengths of the light they reflect, emit, or transmit...

has been found in the sparkling enope squid (Watasenia scintillans), which achieves color vision by the use of three distinct retinal

Retinal

Retinal, also called retinaldehyde or vitamin A aldehyde, is one of the many forms of vitamin A . Retinal is a polyene chromophore, and bound to proteins called opsins, is the chemical basis of animal vision...

molecules (A1, sensitive to red; A2, to purple, and A4, to yellow?) which bind to its opsin

Opsin

Opsins are a group of light-sensitive 35–55 kDa membrane-bound G protein-coupled receptors of the retinylidene protein family found in photoreceptor cells of the retina. Five classical groups of opsins are involved in vision, mediating the conversion of a photon of light into an electrochemical...

.

Unlike many other cephalopods, nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

es do not have good vision; their eye structure is highly developed, but lacks a solid lens

Lens (anatomy)

The crystalline lens is a transparent, biconvex structure in the eye that, along with the cornea, helps to refract light to be focused on the retina. The lens, by changing shape, functions to change the focal distance of the eye so that it can focus on objects at various distances, thus allowing a...

. They have a simple "pinhole

Pinhole camera

A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens and with a single small aperture – effectively a light-proof box with a small hole in one side. Light from a scene passes through this single point and projects an inverted image on the opposite side of the box...

" eye through which water can pass. Instead of vision, the animal is thought to use olfaction

Olfaction

Olfaction is the sense of smell. This sense is mediated by specialized sensory cells of the nasal cavity of vertebrates, and, by analogy, sensory cells of the antennae of invertebrates...

as the primary sense for foraging

Foraging

- Definitions and significance of foraging behavior :Foraging is the act of searching for and exploiting food resources. It affects an animal's fitness because it plays an important role in an animal's ability to survive and reproduce...

, as well as locating or identifying potential mates.

Use of light

Chromatophore

Chromatophores are pigment-containing and light-reflecting cells found in amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans, and cephalopods. They are largely responsible for generating skin and eye colour in cold-blooded animals and are generated in the neural crest during embryonic development...

s - that is, coloured pigments - which they can use in a startling array of fashions. As well as providing camouflage with their background, some cephalopods bioluminesce, shining light downwards to disguise their shadows from any predators that may lurk below. The bioluminescence is produced by bacterial symbionts; the host cephalopod is able to detect the light produced by these organisms. Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by a living organism. Its name is a hybrid word, originating from the Greek bios for "living" and the Latin lumen "light". Bioluminescence is a naturally occurring form of chemiluminescence where energy is released by a chemical reaction in...

may also be used to entice prey, and some species use colourful displays to impress mates, startle predators, or even communicate with one another. It is not certain whether bioluminescence is actually of epithelial origin or if it is a bacterial production.

Colouration

Colouration can be changed in milliseconds as they adapt to their environment, and the pigment cells are expandable by muscular contraction. Colouration is typically more pronounced in near-shore species than those living in the open ocean, whose functions tend to be restricted to camouflage by breaking their outline.Evidence of original colouration has been detected in cephalopod fossils dating as far back as the Silurian

Silurian

The Silurian is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Ordovician Period, about 443.7 ± 1.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Devonian Period, about 416.0 ± 2.8 Mya . As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period's start and end are well identified, but the...

; these orthoconic individuals bore concentric stripes, which are thought to have served as camouflage. Devonian cephalopods bear more complex colour patterns, whose function may be more complex.

Ink

With the exception of the Nautilidae and the species of octopusOctopus

The octopus is a cephalopod mollusc of the order Octopoda. Octopuses have two eyes and four pairs of arms, and like other cephalopods they are bilaterally symmetric. An octopus has a hard beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms...

belonging to the suborder

Order (biology)

In scientific classification used in biology, the order is# a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, family, genus, and species, with order fitting in between class and family...

Cirrina, all known cephalopods have an ink sac, which can be used to expel a cloud of dark ink to confuse predators. This sac is a muscular bag which originated as an extension of the hind gut. It lies beneath the gut and opens into the anus, into which its contents – almost pure melanin

Melanin

Melanin is a pigment that is ubiquitous in nature, being found in most organisms . In animals melanin pigments are derivatives of the amino acid tyrosine. The most common form of biological melanin is eumelanin, a brown-black polymer of dihydroxyindole carboxylic acids, and their reduced forms...

– can be squirted; its proximity to the base of the funnel means the ink can be distributed by ejected water as the cephalopod uses its jet propulsion. The ejected cloud of melanin is usually mixed, upon expulsion, with mucus

Mucus

In vertebrates, mucus is a slippery secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. Mucous fluid is typically produced from mucous cells found in mucous glands. Mucous cells secrete products that are rich in glycoproteins and water. Mucous fluid may also originate from mixed glands, which...

, produced elsewhere in the mantle, and therefore forms a thick cloud, resulting in visual (and possibly chemosensory) impairment of the predator, like a smokescreen. However, a more sophisticated behaviour has been observed, in which the cephalopod releases a cloud, with a greater mucus content, that approximately resembles the cephalopod that released it (this decoy is referred to as a Pseudomorph). This strategy often results in the predator attacking the pseudomorph, rather than its rapidly departing prey. For more information, see Inking behaviors.

The inking behaviour of cephalopods has led to a common name of "inkfish", primarily used in fisheries science and the fishing industry

Fishing industry

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products....

, paralleling the terms white fish

Whitefish (fisheries term)

Whitefish or white fish is a fisheries term referring to several species of demersal fish with fins, particularly cod , whiting , and haddock , but also hake , pollock , or others...

, oily fish

Oily fish

Oily fish have oil in their tissues and in the belly cavity around the gut. Their fillets contain up to 30 percent oil, although this figure varies both within and between species...

, and shellfish

Shellfish

Shellfish is a culinary and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater environments, some kinds are found only in freshwater...

.

Circulatory system

Cephalopods are the only mollusks with a closed circulatory system. Coleoids have two gill heartHeart

The heart is a myogenic muscular organ found in all animals with a circulatory system , that is responsible for pumping blood throughout the blood vessels by repeated, rhythmic contractions...

s (also known as branchial heart

Branchial heart

Branchial hearts are myogenic accessory pumps found in coleoid cephalopods that supplement the action of the main, systemic heart. Each consists of a single chamber and they are always paired, being located at the base of the gills. They pump blood through the gills via the afferent branchial veins...

s) that move blood through the capillaries of the gill

Gill

A gill is a respiratory organ found in many aquatic organisms that extracts dissolved oxygen from water, afterward excreting carbon dioxide. The gills of some species such as hermit crabs have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are kept moist...

s. A single systemic heart then pumps the oxygenated blood through the rest of the body.

Like most molluscs, cephalopods use hemocyanin

Hemocyanin

Hemocyanins are respiratory proteins in the form of metalloproteins containing two copper atoms that reversibly bind a single oxygen molecule . Oxygenation causes a color change between the colorless Cu deoxygenated form and the blue Cu oxygenated form...

, a copper-containing protein, rather than hemoglobin

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein in the red blood cells of all vertebrates, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae, as well as the tissues of some invertebrates...

, to transport oxygen. As a result, their blood is colorless when deoxygenated and turns blue when exposed to air.

Respiration

Cephalopods exchange gasses with the seawater by forcing water through their gills, which are attached to the roof of the organism. Water enters the mantle cavity on the outside of the gills, and the entrance of the mantle cavity closes. When the mantle contracts, water is forced through the gills, which lie between the mantle cavity and the funnel. The water's expulsion through the funnel can be used to power jet propulsion. The gills, which are much more efficient than those of other molluscs, are attached to the ventral surface of the mantle cavity.There is a trade-off with gill size regarding lifestyle. To achieve fast speeds, gills need to be small - water will be passed through them quickly when energy is needed, compensating for their small size. However, organisms which spend most of their time moving slowly along the bottom do not naturally pass much water through their cavity for locomotion; thus they have larger gills, along with complex systems to ensure that water is constantly washing through their gills, even when the organism is stationary. The water flow is controlled by contractions of the radial and circular mantle cavity muscles.

The gills of cephalopods are supported by a skeleton of robust fibrous proteins; the lack of mucopolysaccharides distinguishes this matrix from cartilage. The gills are also thought to be involved in excretion, with NH4+ being swapped with K+ from the seawater.

Locomotion and buoyancy

While all cephalopods can move by jet propulsion, this is a very energy-consuming way to travel compared to the tail propulsion used by fish. The efficiency of a propellor-driven waterjet (i.e. Froude efficiency) is a more efficient model than rocket efficiency. The relative efficiency of jet propulsion decreases further as animal size increases; paralarvae are far more efficient than juvenile and adult individuals. Since the Paleozoic era, as competition with fish produced an environment where efficient motion was crucial to survival, jet propulsion has taken a back role, with fins and tentacles used to maintain a steady velocity.Whilst jet propulsion is never the sole mode of locomotion, the stop-start motion provided by the jets continues to be useful for providing bursts of high speed - not least when capturing prey or avoiding predators. Indeed, it makes cephalopods the fastest marine invertebrates,

and they can out-accelerate most fish.

The jet is supplemented with fin motion; in the squid, the fins flap each time that a jet is released, amplifying the thrust; they are then extended between jets (presumably to avoid sinking).

Oxygenated water is taken into the mantle cavity

Mantle (mollusc)

The mantle is a significant part of the anatomy of molluscs: it is the dorsal body wall which covers the visceral mass and usually protrudes in the form of flaps well beyond the visceral mass itself.In many, but by no means all, species of molluscs, the epidermis of the mantle secretes...

to the gill

Gill

A gill is a respiratory organ found in many aquatic organisms that extracts dissolved oxygen from water, afterward excreting carbon dioxide. The gills of some species such as hermit crabs have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are kept moist...

s and through muscular contraction of this cavity, the spent water is expelled through the hyponome

Hyponome

A siphon is an anatomical structure which is part of the body of aquatic molluscs in three classes: Gastropoda, Bivalvia and Cephalopoda. In other words, a siphon is found in some saltwater and freshwater snails, in some clams, and in octopus, squid and relatives.Siphons in molluscs are tube-like...

, created by a fold in the mantle. The size difference between the posterior and anterior ends of this organ control the speed of the jet the organism can produce. The velocity of the organism can be accurately predicted for a given mass and morhpology of animal. Motion of the cephalopods is usually backward as water is forced out anteriorly through the hyponome, but direction can be controlled somewhat by pointing it in different directions. Some cephalopods accompany this expulsion of water with a gunshot-like popping noise, thought to function to frighten away potential predators.

Cephalopods employ a similar method of propulsion despite their increasing size (as they grow) changing the dynamics of the water in which they find themselves. Thus their paralarvae do not extensively use their fins (which are less efficient at low Reynolds numbers) and primarily use their jets to propel themselves upwards, whereas large adult cephalopods tend to swim less efficiently and with more reliance on their fins.

Some octopus species are also able to walk along the sea bed. Squids and cuttlefish can move short distances in any direction by rippling of a flap of muscle

Muscle

Muscle is a contractile tissue of animals and is derived from the mesodermal layer of embryonic germ cells. Muscle cells contain contractile filaments that move past each other and change the size of the cell. They are classified as skeletal, cardiac, or smooth muscles. Their function is to...

around the mantle.

While most cephalopods float (i.e. are neutrally buoyant

Neutral buoyancy

Neutral buoyancy is a condition in which a physical body's mass equals the mass it displaces in a surrounding medium. This offsets the force of gravity that would otherwise cause the object to sink...

or nearly so; in fact most cephalopods are about 2-3% denser than seawater), they achieve this in different ways.

Some, such as Nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

, allow gas to diffuse into the gap between the mantle and the shell; others allow purer water to ooze from their kidneys, forcing out denser salt water from the body cavity; others, like some fish, accumulate oils in the liver; and some octopuses have a gelatinous body with lighter chlorine

Chlorine

Chlorine is the chemical element with atomic number 17 and symbol Cl. It is the second lightest halogen, found in the periodic table in group 17. The element forms diatomic molecules under standard conditions, called dichlorine...

ion

Ion

An ion is an atom or molecule in which the total number of electrons is not equal to the total number of protons, giving it a net positive or negative electrical charge. The name was given by physicist Michael Faraday for the substances that allow a current to pass between electrodes in a...

s replacing sulfate

Sulfate

In inorganic chemistry, a sulfate is a salt of sulfuric acid.-Chemical properties:...

in the body chemistry.

Shell

NautilusNautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

es are the only extant cephalopods with an external shell. However, all molluscan shells are formed from the ectoderm (outer layer of the embryo); in cuttlefish

Cuttlefish

Cuttlefish are marine animals of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda . Despite their name, cuttlefish are not fish but molluscs....

(Sepia spp.), for example, an invagination of the ectoderm forms during the embryonic period, resulting in a shell that is internal in the adult. The same is true of the chitinous gladius of squid and octopus. Cirrate octopus

Octopus

The octopus is a cephalopod mollusc of the order Octopoda. Octopuses have two eyes and four pairs of arms, and like other cephalopods they are bilaterally symmetric. An octopus has a hard beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms...

es have cartilaginous fin supports, which are sometimes referred to as a "shell vestige" or "gladius". The Incirrina have no vestige of an internal shell, and some squid also lack a gladius. Interestingly, the shelled coleoids do not form a clade or even a paraphyletic group. The Spirula shell begins as an organic structure, and is then very rapidly mineralized. Shells that are "lost" may be lost by resorption of the calcium carbonate component.

Females of the octopus genus Argonauta secrete a specialised paper-thin eggcase in which they reside, and this is popularly regarded as a "shell", although it is not attached to the body of the animal.

The largest group of shelled cephalopods, the ammonite

Ammonite

Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct subclass within the Molluscan class Cephalopoda which are more closely related to living coleoids Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct...

s, are extinct, but their shells are very common as fossil

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals , plants, and other organisms from the remote past...

s.

The deposition of carbonate, leading to a mineralized shell, appears to be related to the acidity of the organic shell matrix (see Mollusc shell

Mollusc shell

The mollusc shell is typically a calcareous exoskeleton which encloses, supports and protects the soft parts of an animal in the phylum Mollusca, which includes snails, clams, tusk shells, and several other classes...

); shell-forming cephalopods have an acidic matrix, whereas the gladius of squid has a basic matrix.

Head appendages

Cephalopods, as the name implies, have muscular appendages extending from their heads and surrounding their mouths. These are used in feeding, mobility, and even reproduction. In coleoidsColeoidea

Subclass Coleoidea, or Dibranchiata, is the grouping of cephalopods containing all the primarily soft-bodied creatures. Unlike its sister group Nautiloidea, whose members have a rigid outer shell for protection, the coleoids have at most an internal bone or shell that is used for buoyancy or support...

they number eight or ten. Decapods such as cuttlefish and squid have five pairs. The longer two, termed tentacle

Tentacle

A tentacle or bothrium is one of usually two or more elongated flexible organs present in animals, especially invertebrates. The term may also refer to the hairs of the leaves of some insectivorous plants. Usually, tentacles are used for feeding, feeling and grasping. Anatomically, they work like...

s, are actively involved in capturing prey; they can lengthen rapidly (in as little as 15 milliseconds). In giant squid

Giant squid

The giant squid is a deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae, represented by as many as eight species...

they may reach a length of 8 metres. They may terminate in a broadened, sucker-coated club. The shorter four pairs are termed arms

Cephalopod arm

A cephalopod arm is distinct from a tentacle, though the terms are often used interchangeably.Generally, cephalopod arms have suckers along most of their length, as opposed to tentacles, which have suckers only near their ends. Octopuses have eight arms and no tentacles, while squid and cuttlefish...

, and are involved in holding and manipulating the captured organism. They too have suckers, on the side closest to the mouth; these help to hold onto the prey. Octopods only have four pairs of sucker-coated arms, as the name suggests.

The tentacle consists of a thick central nerve cord (which must be thick to allow each sucker to be controlled independently) surrounded by circular and radial muscles. Because the volume of the tentacle remains constant, contracting the circular muscles decreases the radius and permits the rapid increase in length. Typically a 70% lengthening is achieved by decreasing the width by 23%. The shorter arms lack this capability.

The size of the tentacle is related to the size of the buccal cavity; larger, stronger tentacles can hold prey as small bites are taken from it; with more numerous, smaller tentacles, prey is swallowed whole, so the mouth cavity must be larger.

Externally shelled nautilids (Nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

and Allonautilus

Allonautilus

The genus Allonautilus contains two species of nautiluses, which differ significantly in terms of morphology from those placed in the sister taxon Nautilus. Allonautilus is now thought to be a descendant of Nautilus and the latter paraphyletic.-External links:*...

) have on the order of 90 finger-like appendages, termed tentacles, which lack suckers but are sticky instead, and are partly retractable.

Feeding

All living cephalopods have a two-part beak; most have a radulaRadula

The radula is an anatomical structure that is used by molluscs for feeding, sometimes compared rather inaccurately to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food enters the esophagus...

, although it is reduced in most octopus and absent altogether in Spirula. They feed by capturing prey with their tentacles, drawing it in to their mouth and taking bites from it. They have a mixture of toxic digestive juices, some of which are manufactured by symbiotic algae, which they eject from their salivary glands onto their captured prey held in their mouth. These juices separate the flesh of their prey from the bone or shell. The salivary gland has a small tooth at its end which can be poked into an organism to digest it from within.

The digestive gland itself is rather short. It has four elements, with food passing through the crop, stomach and caecum before entering the intestine. Most digestion, as well as the absorption of nutrients, occurs in the digestive gland, sometimes called the liver. Nutrients and waste materials are exchanged between the gut and the digestive gland through a pair of connections linking the gland to the junction of the stomach and caecum. Cells in the digestive gland directly release pigmented excretory chemicals into the lumen of the gut, which are then bound with mucus passed through the anus as long dark strings, ejected with the aid of exhaled water from the funnel. Cephalopods tend to concentrate ingested heavy metals in their body tissue.

Radula

The cephalopod radula consists of multiple symmetrical rows of up to nine teeth – thirteen in fossil classes. The organ is reduced or even vestigial in certain octopus species and is absent in Spirula. The teeth may be homodont (i.e. similar in form across a row), heterodont (otherwise), or ctenodont (comb-like). Their height, width and number of cusps is variable between species. The pattern of teeth repeats, but each row may not be identical to the last; in the octopus, for instance, the sequence repeats every five rows.Cephalopod radulae are known from fossil deposits dating back to the Ordovician. They are usually preserved within the cephalopod's body chamber, commonly in conjunction with the mandibles; but this need not always be the case; many radulae are preserved in a range of settings in the Mason Creek.

Radulae are usually difficult to detect, even when they are preserved in fossils, as the rock must weather and crack in exactly the right fashion to expose them; for instance, radulae have only been found in nine of the 43 ammonite genera, and they are rarer still in non-ammonoid forms: only three pre-Mesozoic species possess one.

Excretory system

Most cephalopods possess a single pair of large nephridiaNephridium

A Nephridium is an invertebrate organ which occurs in pairs and function similar to kidneys. Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. They are present in many different invertebrate lines. There are two basic types, metanephridia and protonephridia, but there are other...

. Filtered nitrogenous waste is produced in the pericardial

Pericardium

The pericardium is a double-walled sac that contains the heart and the roots of the great vessels.-Layers:...

cavity of the branchial heart

Branchial heart

Branchial hearts are myogenic accessory pumps found in coleoid cephalopods that supplement the action of the main, systemic heart. Each consists of a single chamber and they are always paired, being located at the base of the gills. They pump blood through the gills via the afferent branchial veins...

s, each of which is connected to a nephridium by a narrow canal. The canal delivers the excreta to a bladder-like renal sac, and also resorbs excess water from the filtrate. Several outgrowths of the lateral vena cava project into the renal sac, continuously inflating and deflating as the branchial hearts beat. This action helps to pump the secreted waste into the sacs, to be released into the mantle cavity through a pore.

Nautilus, unusually, possesses four nephridia, none of which are connected to the pericardial cavities.

Ammonium

The handling of ammoniaAmmonia

Ammonia is a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . It is a colourless gas with a characteristic pungent odour. Ammonia contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to food and fertilizers. Ammonia, either directly or...

is thought to be important in shell formation in terrestrial molluscs, and in other nonmolluscan lineages.

Because protein

Protein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

(i.e. flesh) is a major constituent of the cephalopod diet, large amounts of ammonium

Ammonium

The ammonium cation is a positively charged polyatomic cation with the chemical formula NH. It is formed by the protonation of ammonia...

are produced as waste. The main organs involved with the release of this excess ammonium are the gills.

The rate of this release is the lowest in the shelled cephalopods Nautilus

Nautilus

Nautilus is the common name of marine creatures of cephalopod family Nautilidae, the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina. It comprises six living species in two genera, the type of which is the genus Nautilus...

and Sepia

Sepia (genus)

Sepia is a genus of cuttlefish in the family Sepiidae encompassing some of the best known and most common species. The cuttlebone is relatively ellipsoid in shape...

, probably as a result of their use of nitrogen

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element that has the symbol N, atomic number of 7 and atomic mass 14.00674 u. Elemental nitrogen is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, and mostly inert diatomic gas at standard conditions, constituting 78.08% by volume of Earth's atmosphere...

to fill their shells with gas to produce buoyancy. Other cephalopods use ammonium in a similar way, storing the ion

Ion

An ion is an atom or molecule in which the total number of electrons is not equal to the total number of protons, giving it a net positive or negative electrical charge. The name was given by physicist Michael Faraday for the substances that allow a current to pass between electrodes in a...

s (as ammonium chloride

Ammonium chloride

Ammonium chloride NH4Cl is an inorganic compound with the formula NH4Cl. It is a white crystalline salt that is highly soluble in water. Solutions of ammonium chloride are mildly acidic. Sal ammoniac is a name of natural, mineralogical form of ammonium chloride...

) themselves to reduce their overall density and thus become more buoyant.

Reproduction and life cycle

With a few exceptions, Coleoidea live short lives with rapid growth. Most of the energy extracted from their food is used for growing. The penis in most male Coleoidea is a long and muscular end of the gonoduct used to transfer spermatophores to a modified arm called a hectocotylusHectocotylus

A hectocotylus is one of the arms of the male of most kinds of cephalopods that is modified in various ways to effect the fertilization of the female's eggs. It is a specialized, extended muscular hydrostat used to store spermatophores, the male gametophore...

. That, in turn, is used to transfer the spermatophores to the female. In species where the hectocotylus is missing, the penis is long and able to extend beyond the mantle cavity and transfers the spermatophores directly to the female. Deep water squid have the greatest known penis length relative to body size of all mobile animals, second in the entire animal kingdom only to certain sessile barnacle

Barnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod belonging to infraclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile suspension feeders, and have...

s. Penis elongation in Onykia ingens may result in a penis that is as long as the mantle, head and arms combined.

Most cephalopods tend towards a semelparous reproduction strategy; they lay many small eggs in one batch and die afterwards. The Nautiloidea, on the other hand, stick to iteroparity; they produce a few large eggs in each batch and live for a long time.

External sexual characteristics are lacking in cephalopods, so cephalopods use colour communication. A courting male will approach a likely looking opposite number flashing his brightest colours, often in rippling displays. If the other cephalopod is female and receptive, her skin will change colour to become pale, and mating will occur. If the other cephalopod remains brightly coloured, it is taken as a warning.

The male has a sperm-carrying arm, known as the hectocotylous arm, with which to impregnate the female. In many cephalopods, mating occurs head to head and the male may simply transfer sperm to the female. Others may detach the sperm-carrying arm and leave it attached to the female. In the paper nautilus, this arm remains active and wriggling for some time, prompting the zoologists who discovered it to conclude it was some sort of worm-like parasite. It was duly given a genus name Hectocotylus, which held for some time until the mistake was discovered.

Nidamental gland

Nidamental gland

The nidamental gland is an internal organ found in some elasmobranchs and certain molluscs, including cephalopods and gastropods....

s are involved in the secretion of egg cases or the gelatinous substance comprising egg masses. The eggs may be brooded: female paper nautilus construct a shelter for the young, while Gonatiid squid carry a larva-laden membrane from the hooks on their arms. Other cephalopods deposit their young under rocks and aerate them with their tentacles hatching. Often, though, the eggs are left to their own devices; many squid lay sausage-like bunches of eggs in crevices or occasionally on the sea floor. Cuttlefish

Cuttlefish

Cuttlefish are marine animals of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda . Despite their name, cuttlefish are not fish but molluscs....

lay their eggs separately in cases and attach them to coral or algal fronds. Fossilised egg clutches show that ammonites also laid clutches of eggs.

Cephalopods are occasionally long-lived, especially in the deep water or polar forms, but most of the group live fast and die young, maturing rapidly to their adult size. Some may gain as much as 12% of their body mass each day. Most live for one to two years, reproducing and then dying shortly thereafter.

To free up resources for reproduction, many squid are known to resorb the muscle tissue of their mantle and tentacles, breaking down the tissue and using the energy contained therein to produce more gametes.

Embryology

Unlike most other molluscs, cephalopods do not have a distinct larvaLarva

A larva is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle...

l stage. The fertilised ovum

Ovum