Constitutional Reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Encyclopedia

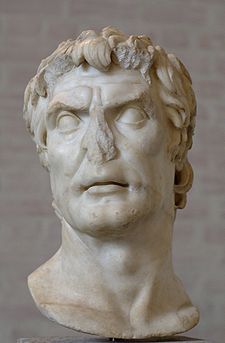

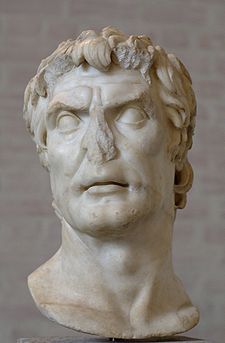

The Constitutional Reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla were a series of laws that were enacted by the Roman Dictator

Lucius Cornelius Sulla between 82 and 80 BC, which reformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic

. In the decades before Sulla had become Dictator, a series of political developments occurred which severely weakened aristocratic control over the Roman Constitution

. Sulla's Dictatorship constituted one of the most significant developments in the History of the Constitution of the Roman Republic

, and it served as a warning for the coming civil war, which ultimately would destroy the Roman Republic

and create the Roman Empire

. Sulla, who had witnessed chaos at the hands of his political enemies in the years before his Dictatorship, was naturally conservative. He believed that the underlying flaw in the Roman constitution was the increasingly aggressive democracy, which expressed itself through the Roman assemblies

, and as such, he sought to strengthen the Roman Senate

. He retired in 79 BC, and died in 78 BC, having believed that he had corrected the constitutional flaw. His constitution would be mostly rescinded by two of his former lieutenants, Pompey Magnus

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

, less than ten years after his death. But what he did not realize was that it was he himself who actually had illustrated the underlying flaw in the Roman constitution: that it was the army, and not the Roman senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state. The precedent he produced would be emulated less than forty years later by an individual whom he almost had executed, Julius Caesar

, and as such, he played a critical early role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

, had forced citizens to leave their farms, which often caused those farms to fall into a state of disrepair. This situation was made worse during the Second Punic War

, when Hannibal fought the Romans throughout Italy, and the Romans adopted a strategy of attrition and guerilla warfare in response. When the soldiers returned from the battlefield, they often had to sell their farms to pay their debts, and the landed aristocracy quickly bought these farms at discounted prices. The wars had also brought to Rome a great surplus of inexpensive slave labor, which the landed aristocrats used to staff their new farms. Soon the masses of unemployed Plebeians began to flood into Rome, and into the ranks of the legislative assemblies. At the same time, the aristocracy was becoming extremely rich, and with the destruction of Rome's great commercial rival of Carthage

, even more opportunities for profit became available. While the aristocrats spent their time exploiting new opportunities for profit, Rome was conquering new civilizations in the east. These civilizations were often highly developed, and as such they opened up a world of luxury to the Romans. Up until this point, most Romans had only known a simple life, but as both wealth and eastern luxuries became available at the same time, an era of ruinous decadence followed. The sums that were spent on these luxuries had no precedent in prior Roman history, and although several laws were enacted to stem this tide of decadence, these laws ultimately had no effect.

By the end of this era, Rome had become full of unemployed Plebeians. They then began filling the ranks of the assemblies, and the fact that they were no longer away from Rome made it easier for them to vote. In the principle legislative assembly, the Plebeian Council

, any individual voted in the Tribe to which his ancestors had belonged. Thus, most of these newly unemployed Plebeians belonged to one of the thirty-one rural Tribes, rather than one of the four urban Tribes, and the unemployed Plebeians soon acquired so much political power that the Plebeian Council became highly populist. These Plebeians were often angry with the aristocracy, which further exacerbated the class tensions. Their economic state usually led them to vote for the candidate who offered the most for them, or at least for the candidate whose games or whose bribes were the most magnificent. The fact that they were usually uninformed as to the issues before them didn't matter, because they usually sold their votes to the highest bidder anyway. Bribery became such a problem that major reforms were ultimately passed, in particular the requirement that all votes be by secret ballot. A new culture of dependency was emerging, which would look to any populist leader for relief.

Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Gracchus

was elected Plebeian Tribune (the chief representative of the people) in 133 BC, and as Tribune, he attempted to enact a law that would have distributed some of the public land amongst Rome's veterans. The aristocrats, who stood to lose an enormous amount of money, were bitterly opposed to this proposal. Tiberius submitted this law to the Plebeian Council

, but the law was vetoed by a Tribune named Marcus Octavius

, and so Tiberius used the Plebeian Council to impeach Octavius. The theory, that a representative of the people ceases to be one when he acts against the wishes of the people, was repugnant to the genius of Roman constitutional theory. If carried to its logical end, this theory removed all constitutional restraints on the popular will, and put the state under the absolute control of a temporary popular majority. This theory ultimately found its logical end under the future democratic empire of the military populist Julius Caesar. The law was enacted, but Tiberius was murdered when he stood for reelection to the Tribunate. The ten years that followed his death were politically inactive. The only important development was in the growing strength of the democratic opposition to the aristocracy.

Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected Plebeian Tribune in 123 BC. Gaius Gracchus'

ultimate goal was to weaken the senate and to strengthen the democratic forces, so he first enacted a law which put the knights (equites, or apolitical businessmen of the upper classes) on the jury courts instead of the senators. He then passed a grain law which greatly disadvantaged the provincial governors, most of whom were senators and thus who could no longer serve on the jury courts. The knights, on the other hand, stood to profit greatly from these grain reforms, and so the result was that Gaius managed to turn the most powerful class of non-senators against the senate. In the past, the senate eliminated political rivals either by establishing special judicial commissions or by passing a senatus consultum ultimum

("ultimate decree of the senate"). Both devices allowed the senate to bypass the ordinary due process rights that all citizens had. Gaius outlawed the judicial commissions, and declared the senatus consultum ultimum to be unconstitutional. Gaius then proposed a law which granted citizenship rights to Rome's Italian allies, but the selfish democracy in Rome, which jealously guarded its privileged status, deserted him over this proposal. He stood for reelection to a third term in 121 BC, but was defeated and then murdered. The democracy, however, had finally realized how weak the senate had become.

Several years later, a new power had emerged in Asia. In 88 BC, a Roman army was sent to put down that power, king Mithridates

Several years later, a new power had emerged in Asia. In 88 BC, a Roman army was sent to put down that power, king Mithridates

of Pontus

, but was defeated. Lucius Cornelius Sulla

had been elected Consul

(the chief-executive of the Roman Republic) for the year, and was ordered by the senate to assume command of the war against Mithridates. Gaius Marius

, a former Consul and a member of the democratic ("populare") party, was a bitter political rival of Sulla. Marius had a Plebeian Tribune

revoke Sulla's command of the war against Mithridates, so Sulla, a member of the aristocratic ("optimate") party, brought his army back to Italy and marched on Rome. Marius fled, and his supporters either fled or were murdered by Sulla. Sulla had become so angry at Marius' Tribune that he passed a law that was intended to permanently weaken the Tribunate. He then returned to his war against Mithridates, and with Sulla gone, the populares under Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna

soon took control of the city. The populare record was not one to be proud of, as they had reelected Marius to the Consulship several times without observing the required ten year interval. They also transgressed democracy by advancing un-elected individuals to magisterial office, and by substituting magisterial edicts for popular legislation. Sulla soon made peace with Mithridates, and in 83 BC, he returned to Rome, overcame all resistance, and captured the city again. Sulla was installed as Dictator

, and his supporters then slaughtered most of Marius' supporters, although one such supporter, a 17-year-old populare (and the son-in-law of Cinna) named Julius Caesar, was ultimately spared.

Sulla, who had observed the violent results of radical populare reforms (in particular those under Marius and Cinna), was naturally conservative, and so his conservatism was more reactionary than it was visionary. As such, he sought to strengthen the aristocracy, and thus the senate. Sulla retained his earlier reforms, which required senate approval before any bill could be submitted to the Plebeian Council

(the principal popular assembly), and which had also restored the older, more aristocratic ("Servian

") organization to the Century Assembly

(assembly of soldiers). Up until the 3rd century BC, the Plebeian Council was legally required to attain senatorial authorization before enacting any law, while the Century Assembly had been organized in such an aristocratic manner as to have denied the lower classes any political power. The reforms which had altered these two processes had marked the end to the Conflict of the Orders

, during which time the Plebeians had sought political equality with the aristocratic Patrician class.

Sulla, himself a Patrician and thus ineligible for election to the office of Plebeian Tribune

, thoroughly disliked the office. Some of his dislike may have been acquired when Marius' Tribune had revoked Sulla's authorization to command the war against Mithridates. As Sulla viewed the office, the Tribunate was especially dangerous, which was in part due to its radical past, and so his intention was to not only deprive the Tribunate of power, but also of prestige. The reforms of the Gracchi Tribunes were one such example of its radical past, but by no means were they the only such examples. Over the past three-hundred years, the Tribunes had been the officers most responsible for the loss of power by the aristocracy. Since the Tribunate was the principal means through which the democracy of Rome had always asserted itself against the aristocracy, it was of paramount importance to Sulla that he cripple the office. Through his reforms to the Plebeian Council, Tribunes lost the power to initiate legislation. Sulla then prohibited ex-Tribunes from ever holding any other office, so ambitious individuals would no longer seek election to the Tribunate, since such an election would end their political career. Finally, Sulla revoked the power of the Tribunes to veto acts of the senate. This reform was of dubious constitutionality at best, and was outright sacrilegious at worst. Ultimately, the Tribunes, and thus the People of Rome

, became powerless.

Sulla then weakened the magisterial offices by increasing the number of magistrates who were elected in any given year, and required that all newly-elected Quaestor

s be given automatic membership in the senate. These two reforms were enacted primarily so as to allow Sulla to increase the size of the senate from 300 to 600 senators. This removed the need for the Censor to draw up a list of senators, since there were always more than enough former magistrates to fill the senate. The Censorship was the most prestigious of all magisterial offices, and by reducing the power of the Censors, this particular reform further helped to reduce the prestige of all magisterial offices. In addition, by increasing the number of magistrates, the prestige of each magistrate was reduced, and the potential for obstruction within each magisterial college was maximized. This, so the theory went, would further increase the importance of the senate as the principal organ of constitutional government.

To further solidify the prestige and authority of the senate, Sulla transferred the control of the courts from the knights, who had held control since the Gracchi reforms, to the senators. This, along with the increase in the number of courts, further added to the power that was already held by the senators. He also codified, and thus established definitively, the cursus honorum

, which required an individual to reach a certain age and level of experience before running for any particular office. In this past, the cursus honorum had been observed through precedent, but had never actually been codified. By requiring senators to be more experienced than they had been in the past, he hoped to add to the prestige, and thus the authority, of the senate.

Sulla also wanted to reduce the risk that a future general might attempt to seize power, as he himself had done. To reduce this risk, he reaffirmed the requirement that any individual wait for ten years before being reelected to any office. Sulla then established a system where all Consuls and Praetors served in Rome during their year in office, and then commanded a provincial army as a governor for the year after they left office. The number of Praetors (the second-highest ranking magistrate, after the Consul

) were increased, so that there would be enough magistrates for each province under this system. These two reforms were meant to ensure that no governor would be able to command the same army for an extended period of time, so as to minimize the threat that another general might attempt to march on Rome.

In 77 BC, the senate sent one of Sulla's former lieutenants, Gnaeus Pompey Magnus

, to put down an uprising in Spain. By 71 BC, Pompey returned to Rome after having completed his mission, and around the same time, another of Sulla's former lieutenants, Marcus Licinius Crassus

, had just put down a slave revolt in Italy. Upon their return, Pompey and Crassus found the populare party fiercely attacking Sulla's constitution, and so they attempted to forge an agreement with the populare party. If both Pompey and Crassus were elected Consul in 70 BC, they would dismantle the more obnoxious components of Sulla's constitution. The promise of both Pompey and Crassus, aided by the presence of both of their armies outside of the gates of Rome, helped to 'persuade' the populares to elect the two to the Consulship. As soon as they were elected, they dismantled most of Sulla's constitution.

In 63 BC, a conspiracy led by Lucius Sergius Catiline attempted to overthrow the Republic, and install Catiline as master of the state. Catiline and his supporters simply followed in Sulla's footsteps. Ultimately, however, the conspiracy was discovered and the conspirators were killed. In January of 49 BC, after the senate had refused to renew his appointment as governor, Julius Caesar

followed in Sulla's footsteps, marched on Rome, and made himself Dictator. This time, however, the Roman Republic was not as lucky, and the civil war that Caesar began would not end until 27 BC, with the creation of the Roman Empire

.

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

Lucius Cornelius Sulla between 82 and 80 BC, which reformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic

Constitution of the Roman Republic

The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten, uncodified, and constantly evolving...

. In the decades before Sulla had become Dictator, a series of political developments occurred which severely weakened aristocratic control over the Roman Constitution

Roman Constitution

The Roman Constitution was an uncodified set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The Roman constitution was not formal or even official, largely unwritten and constantly evolving. Concepts that originated in the Roman constitution live on in constitutions to this day...

. Sulla's Dictatorship constituted one of the most significant developments in the History of the Constitution of the Roman Republic

History of the Constitution of the Roman Republic

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Republic is a study of the ancient Roman Republic that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC until the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The constitutional history of the Roman...

, and it served as a warning for the coming civil war, which ultimately would destroy the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

and create the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. Sulla, who had witnessed chaos at the hands of his political enemies in the years before his Dictatorship, was naturally conservative. He believed that the underlying flaw in the Roman constitution was the increasingly aggressive democracy, which expressed itself through the Roman assemblies

Roman assemblies

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital...

, and as such, he sought to strengthen the Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

. He retired in 79 BC, and died in 78 BC, having believed that he had corrected the constitutional flaw. His constitution would be mostly rescinded by two of his former lieutenants, Pompey Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and politician who commanded the right wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the...

, less than ten years after his death. But what he did not realize was that it was he himself who actually had illustrated the underlying flaw in the Roman constitution: that it was the army, and not the Roman senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state. The precedent he produced would be emulated less than forty years later by an individual whom he almost had executed, Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

, and as such, he played a critical early role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

Before the Gracchi (287–133 BC)

By the middle of the 2nd century BC, the Plebeians (commoners) saw a worsening economic situation. The long military campaigns, in particular those of the Punic WarsPunic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

, had forced citizens to leave their farms, which often caused those farms to fall into a state of disrepair. This situation was made worse during the Second Punic War

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War and The War Against Hannibal, lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the participation of the Berbers on...

, when Hannibal fought the Romans throughout Italy, and the Romans adopted a strategy of attrition and guerilla warfare in response. When the soldiers returned from the battlefield, they often had to sell their farms to pay their debts, and the landed aristocracy quickly bought these farms at discounted prices. The wars had also brought to Rome a great surplus of inexpensive slave labor, which the landed aristocrats used to staff their new farms. Soon the masses of unemployed Plebeians began to flood into Rome, and into the ranks of the legislative assemblies. At the same time, the aristocracy was becoming extremely rich, and with the destruction of Rome's great commercial rival of Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

, even more opportunities for profit became available. While the aristocrats spent their time exploiting new opportunities for profit, Rome was conquering new civilizations in the east. These civilizations were often highly developed, and as such they opened up a world of luxury to the Romans. Up until this point, most Romans had only known a simple life, but as both wealth and eastern luxuries became available at the same time, an era of ruinous decadence followed. The sums that were spent on these luxuries had no precedent in prior Roman history, and although several laws were enacted to stem this tide of decadence, these laws ultimately had no effect.

By the end of this era, Rome had become full of unemployed Plebeians. They then began filling the ranks of the assemblies, and the fact that they were no longer away from Rome made it easier for them to vote. In the principle legislative assembly, the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

, any individual voted in the Tribe to which his ancestors had belonged. Thus, most of these newly unemployed Plebeians belonged to one of the thirty-one rural Tribes, rather than one of the four urban Tribes, and the unemployed Plebeians soon acquired so much political power that the Plebeian Council became highly populist. These Plebeians were often angry with the aristocracy, which further exacerbated the class tensions. Their economic state usually led them to vote for the candidate who offered the most for them, or at least for the candidate whose games or whose bribes were the most magnificent. The fact that they were usually uninformed as to the issues before them didn't matter, because they usually sold their votes to the highest bidder anyway. Bribery became such a problem that major reforms were ultimately passed, in particular the requirement that all votes be by secret ballot. A new culture of dependency was emerging, which would look to any populist leader for relief.

Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus (133–121 BC)

Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman Populares politician of the 2nd century BC and brother of Gaius Gracchus. As a plebeian tribune, his reforms of agrarian legislation caused political turmoil in the Republic. These reforms threatened the holdings of rich landowners in Italy...

was elected Plebeian Tribune (the chief representative of the people) in 133 BC, and as Tribune, he attempted to enact a law that would have distributed some of the public land amongst Rome's veterans. The aristocrats, who stood to lose an enormous amount of money, were bitterly opposed to this proposal. Tiberius submitted this law to the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

, but the law was vetoed by a Tribune named Marcus Octavius

Marcus Octavius

Marcus Octavius was a Roman tribune and a major rival of Tiberius Gracchus. A serious and discreet person, he earned himself a reputation as an influential orator. Though originally close friends, Octavius became alarmed by Gracchus's populist agenda and, at the behest of the Roman senate,...

, and so Tiberius used the Plebeian Council to impeach Octavius. The theory, that a representative of the people ceases to be one when he acts against the wishes of the people, was repugnant to the genius of Roman constitutional theory. If carried to its logical end, this theory removed all constitutional restraints on the popular will, and put the state under the absolute control of a temporary popular majority. This theory ultimately found its logical end under the future democratic empire of the military populist Julius Caesar. The law was enacted, but Tiberius was murdered when he stood for reelection to the Tribunate. The ten years that followed his death were politically inactive. The only important development was in the growing strength of the democratic opposition to the aristocracy.

Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected Plebeian Tribune in 123 BC. Gaius Gracchus'

Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman Populari politician in the 2nd century BC and brother of the ill-fated reformer Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus...

ultimate goal was to weaken the senate and to strengthen the democratic forces, so he first enacted a law which put the knights (equites, or apolitical businessmen of the upper classes) on the jury courts instead of the senators. He then passed a grain law which greatly disadvantaged the provincial governors, most of whom were senators and thus who could no longer serve on the jury courts. The knights, on the other hand, stood to profit greatly from these grain reforms, and so the result was that Gaius managed to turn the most powerful class of non-senators against the senate. In the past, the senate eliminated political rivals either by establishing special judicial commissions or by passing a senatus consultum ultimum

Senatus consultum ultimum

Senatus consultum ultimum , more properly senatus consultum de re publica defendenda is the modern term given to a decree of the Roman Senate during the late Roman Republic passed in times of emergency...

("ultimate decree of the senate"). Both devices allowed the senate to bypass the ordinary due process rights that all citizens had. Gaius outlawed the judicial commissions, and declared the senatus consultum ultimum to be unconstitutional. Gaius then proposed a law which granted citizenship rights to Rome's Italian allies, but the selfish democracy in Rome, which jealously guarded its privileged status, deserted him over this proposal. He stood for reelection to a third term in 121 BC, but was defeated and then murdered. The democracy, however, had finally realized how weak the senate had become.

Sulla's constitution (82–80 BC)

Mithridates VI of Pontus

Mithridates VI or Mithradates VI Mithradates , from Old Persian Mithradatha, "gift of Mithra"; 134 BC – 63 BC, also known as Mithradates the Great and Eupator Dionysius, was king of Pontus and Armenia Minor in northern Anatolia from about 120 BC to 63 BC...

of Pontus

Pontus

Pontus or Pontos is a historical Greek designation for a region on the southern coast of the Black Sea, located in modern-day northeastern Turkey. The name was applied to the coastal region in antiquity by the Greeks who colonized the area, and derived from the Greek name of the Black Sea: Πόντος...

, but was defeated. Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

had been elected Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

(the chief-executive of the Roman Republic) for the year, and was ordered by the senate to assume command of the war against Mithridates. Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius was a Roman general and statesman. He was elected consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his dramatic reforms of Roman armies, authorizing recruitment of landless citizens, eliminating the manipular military formations, and reorganizing the...

, a former Consul and a member of the democratic ("populare") party, was a bitter political rival of Sulla. Marius had a Plebeian Tribune

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

revoke Sulla's command of the war against Mithridates, so Sulla, a member of the aristocratic ("optimate") party, brought his army back to Italy and marched on Rome. Marius fled, and his supporters either fled or were murdered by Sulla. Sulla had become so angry at Marius' Tribune that he passed a law that was intended to permanently weaken the Tribunate. He then returned to his war against Mithridates, and with Sulla gone, the populares under Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Lucius Cornelius Cinna was a four-time consul of the Roman Republic, serving four consecutive terms from 87 to 84 BC, and a member of the ancient Roman Cinna family of the Cornelii gens....

soon took control of the city. The populare record was not one to be proud of, as they had reelected Marius to the Consulship several times without observing the required ten year interval. They also transgressed democracy by advancing un-elected individuals to magisterial office, and by substituting magisterial edicts for popular legislation. Sulla soon made peace with Mithridates, and in 83 BC, he returned to Rome, overcame all resistance, and captured the city again. Sulla was installed as Dictator

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

, and his supporters then slaughtered most of Marius' supporters, although one such supporter, a 17-year-old populare (and the son-in-law of Cinna) named Julius Caesar, was ultimately spared.

Sulla, who had observed the violent results of radical populare reforms (in particular those under Marius and Cinna), was naturally conservative, and so his conservatism was more reactionary than it was visionary. As such, he sought to strengthen the aristocracy, and thus the senate. Sulla retained his earlier reforms, which required senate approval before any bill could be submitted to the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

(the principal popular assembly), and which had also restored the older, more aristocratic ("Servian

Century Assembly

The Century Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial...

") organization to the Century Assembly

Century Assembly

The Century Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial...

(assembly of soldiers). Up until the 3rd century BC, the Plebeian Council was legally required to attain senatorial authorization before enacting any law, while the Century Assembly had been organized in such an aristocratic manner as to have denied the lower classes any political power. The reforms which had altered these two processes had marked the end to the Conflict of the Orders

Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, also referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the Plebeians and Patricians of the ancient Roman Republic, in which the Plebeians sought political equality with the Patricians. It played a major role in the development of the...

, during which time the Plebeians had sought political equality with the aristocratic Patrician class.

Sulla, himself a Patrician and thus ineligible for election to the office of Plebeian Tribune

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

, thoroughly disliked the office. Some of his dislike may have been acquired when Marius' Tribune had revoked Sulla's authorization to command the war against Mithridates. As Sulla viewed the office, the Tribunate was especially dangerous, which was in part due to its radical past, and so his intention was to not only deprive the Tribunate of power, but also of prestige. The reforms of the Gracchi Tribunes were one such example of its radical past, but by no means were they the only such examples. Over the past three-hundred years, the Tribunes had been the officers most responsible for the loss of power by the aristocracy. Since the Tribunate was the principal means through which the democracy of Rome had always asserted itself against the aristocracy, it was of paramount importance to Sulla that he cripple the office. Through his reforms to the Plebeian Council, Tribunes lost the power to initiate legislation. Sulla then prohibited ex-Tribunes from ever holding any other office, so ambitious individuals would no longer seek election to the Tribunate, since such an election would end their political career. Finally, Sulla revoked the power of the Tribunes to veto acts of the senate. This reform was of dubious constitutionality at best, and was outright sacrilegious at worst. Ultimately, the Tribunes, and thus the People of Rome

SPQR

SPQR is an initialism from a Latin phrase, Senatus Populusque Romanus , referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic, and used as an official emblem of the modern day comune of Rome...

, became powerless.

Sulla then weakened the magisterial offices by increasing the number of magistrates who were elected in any given year, and required that all newly-elected Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

s be given automatic membership in the senate. These two reforms were enacted primarily so as to allow Sulla to increase the size of the senate from 300 to 600 senators. This removed the need for the Censor to draw up a list of senators, since there were always more than enough former magistrates to fill the senate. The Censorship was the most prestigious of all magisterial offices, and by reducing the power of the Censors, this particular reform further helped to reduce the prestige of all magisterial offices. In addition, by increasing the number of magistrates, the prestige of each magistrate was reduced, and the potential for obstruction within each magisterial college was maximized. This, so the theory went, would further increase the importance of the senate as the principal organ of constitutional government.

To further solidify the prestige and authority of the senate, Sulla transferred the control of the courts from the knights, who had held control since the Gracchi reforms, to the senators. This, along with the increase in the number of courts, further added to the power that was already held by the senators. He also codified, and thus established definitively, the cursus honorum

Cursus honorum

The cursus honorum was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in both the Roman Republic and the early Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The cursus honorum comprised a mixture of military and political administration posts. Each office had a minimum...

, which required an individual to reach a certain age and level of experience before running for any particular office. In this past, the cursus honorum had been observed through precedent, but had never actually been codified. By requiring senators to be more experienced than they had been in the past, he hoped to add to the prestige, and thus the authority, of the senate.

Sulla also wanted to reduce the risk that a future general might attempt to seize power, as he himself had done. To reduce this risk, he reaffirmed the requirement that any individual wait for ten years before being reelected to any office. Sulla then established a system where all Consuls and Praetors served in Rome during their year in office, and then commanded a provincial army as a governor for the year after they left office. The number of Praetors (the second-highest ranking magistrate, after the Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

) were increased, so that there would be enough magistrates for each province under this system. These two reforms were meant to ensure that no governor would be able to command the same army for an extended period of time, so as to minimize the threat that another general might attempt to march on Rome.

The fate of Sulla's constitution (70–27 BC)

Sulla resigned his Dictatorship in 80 BC, was elected Consul one last time, and died in 78 BC. While he thought that he had firmly established aristocratic rule, his own career had illustrated the fatal weaknesses in the constitution. Ultimately, it was the army, and not the senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state.In 77 BC, the senate sent one of Sulla's former lieutenants, Gnaeus Pompey Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

, to put down an uprising in Spain. By 71 BC, Pompey returned to Rome after having completed his mission, and around the same time, another of Sulla's former lieutenants, Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and politician who commanded the right wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the...

, had just put down a slave revolt in Italy. Upon their return, Pompey and Crassus found the populare party fiercely attacking Sulla's constitution, and so they attempted to forge an agreement with the populare party. If both Pompey and Crassus were elected Consul in 70 BC, they would dismantle the more obnoxious components of Sulla's constitution. The promise of both Pompey and Crassus, aided by the presence of both of their armies outside of the gates of Rome, helped to 'persuade' the populares to elect the two to the Consulship. As soon as they were elected, they dismantled most of Sulla's constitution.

In 63 BC, a conspiracy led by Lucius Sergius Catiline attempted to overthrow the Republic, and install Catiline as master of the state. Catiline and his supporters simply followed in Sulla's footsteps. Ultimately, however, the conspiracy was discovered and the conspirators were killed. In January of 49 BC, after the senate had refused to renew his appointment as governor, Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

followed in Sulla's footsteps, marched on Rome, and made himself Dictator. This time, however, the Roman Republic was not as lucky, and the civil war that Caesar began would not end until 27 BC, with the creation of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

See also

Primary sources

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius