Cordobazo

Encyclopedia

Córdoba, Argentina

Córdoba is a city located near the geographical center of Argentina, in the foothills of the Sierras Chicas on the Suquía River, about northwest of Buenos Aires. It is the capital of Córdoba Province. Córdoba is the second-largest city in Argentina after the federal capital Buenos Aires, with...

, in the end of May 1969, during the military dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía

Juan Carlos Onganía

Juan Carlos Onganía Carballo was de facto president of Argentina from 29 June 1966 to 8 June 1970. He rose to power as military dictator after toppling, in a coup d’état self-named Revolución Argentina , the democratically elected president Arturo Illia .-Economic and social...

, which occurred a few days after the Rosariazo

Rosariazo

The Rosariazo was a protest movement that consisted in demonstrations and strikes, in Rosario, , between May and September 1969, during the military dictatorial rule of de facto President General Juan Carlos Onganía...

, and a year after the French May '68. Contrary to previous protests, the Cordobazo did not correspond to previous struggles, headed by Marxist workers' leaders, but associated students and workers in the same struggle against the junta

Military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a form of government where in the political power resides with the military. It is similar but not identical to a stratocracy, a state ruled directly by the military....

.

On 29 May 1969 there was a general strike

General strike

A general strike is a strike action by a critical mass of the labour force in a city, region, or country. While a general strike can be for political goals, economic goals, or both, it tends to gain its momentum from the ideological or class sympathies of the participants...

in the city of Córdoba, which brought police repression and a civil uprising, an episode later termed the Cordobazo. The next day the CGT de los Argentinos, headed in Cordoba by Agustín Tosco

Agustín Tosco

Agustín Gringo Tosco was an Argentine union leader, member of the CGT de los Argentinos and an important participant in the historic local uprising known as the Cordobazo.-Thought and maturity:At 27 years old, he was the general secretary for Luz y Fuerza...

, called for national strike.

Context

General Onganía had taken power during the 1966 coup, self-named Revolución Argentina (Argentine Revolution), which had toppled President Arturo Illia (Radical Civic UnionRadical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union is a political party in Argentina. The party's positions on issues range from liberal to social democratic. The UCR is a member of the Socialist International. Founded in 1891 by radical liberals, it is the oldest political party active in Argentina...

, UCR). Onganía's regime immediately suspended the right to strike, froze workers' wages, desactivated the Commission on Minimum Wages, while his Minister of Economy, Adalbert Krieger Vasena, decreed a 40% devaluation of the peso

Argentine peso

The peso is the currency of Argentina, identified by the symbol $ preceding the amount in the same way as many countries using dollar currencies. It is subdivided into 100 centavos. Its ISO 4217 code is ARS...

. Age of retirement was also extended.

Onganía had also implemented the "law on repression of Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

" and had ordered the Dirección de Investigación de Políticas Antidemocráticas (DIPA) political police to detain political activists and trade-unionists who did not care to cooperate with him in the "participationist" policies, and, considering universities as "centers of subversion and communism", had also retroceded on the 1918 University Reform (which had found its origins in students' protests in Córdoba), violently expelling from universities teachers and students in the Noche de los Bastones Largos.

Furthermore, Onganía was attempting to impose corporatism

Corporatism

Corporatism, also known as corporativism, is a system of economic, political, or social organization that involves association of the people of society into corporate groups, such as agricultural, business, ethnic, labor, military, patronage, or scientific affiliations, on the basis of common...

in Argentina. In this context, the important industrial hub of Córdoba was one of the experimental place of corporatinist policies, implemented by the appointed governor Carlos Caballero.

Popular uprising

On 13 May 1969, in Tucumán, former workers of a sugar mill took the factory and its manager as hostage, asking for overdue payments.

On 14 May, in Córdoba, automobile industry workers protested the elimination of the Saturday rest.

On 15 May, the University of Corrientes

Corrientes

Corrientes is the capital city of the province of Corrientes, Argentina, located on the eastern shore of the Paraná River, about from Buenos Aires and from Posadas, on National Route 12...

increased the price of food tickets in its cafeteria fivefold, and the ensuing protest ended up with one student, Juan José Cabral, killed by the police (see Correntinazo).

On 17 May, the student Adolfo Bello was killed during a protest in Rosario (see Rosariazo

Rosariazo

The Rosariazo was a protest movement that consisted in demonstrations and strikes, in Rosario, , between May and September 1969, during the military dictatorial rule of de facto President General Juan Carlos Onganía...

).

On 21 May, the police killed the 15-year-old student Luis Blanco during a silent march of 4,000 persons in Rosario, in commemoration of Bello's death. Rosario is declared by the authorities an emergency zone under military jurisdiction.

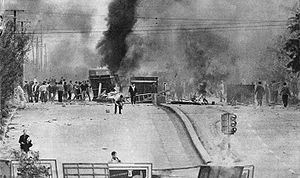

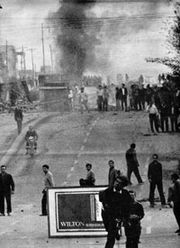

On 29 May 1969, the police shot dead the first victim of the Cordobazo, killing Máximo Mena, which triggered further demonstrations and rioting. Progressively, the population took control of most of the city, setting up barricades to defend themselves. They burnt several administrative centers, as well as the headquarters of the foreign firms, which symbolized Vasena's economic policies, of Citroën

Citroën

Citroën is a major French automobile manufacturer, part of the PSA Peugeot Citroën group.Founded in 1919 by French industrialist André-Gustave Citroën , Citroën was the first mass-production car company outside the USA and pioneered the modern concept of creating a sales and services network that...

and Xerox

Xerox

Xerox Corporation is an American multinational document management corporation that produced and sells a range of color and black-and-white printers, multifunction systems, photo copiers, digital production printing presses, and related consulting services and supplies...

, although they then accompanied the firebombers in order to impede the fire from extending itself to other city blocks.

On the night of 29 to 30 May 1969, Onganía decided to send the military to crush the uprising. Meanwhile, the headquarters of the CGT de los Argentinos (CGTA, an off-shoot of the General Confederation of Labour

General Confederation of Labour (Argentina)

The General Confederation of Labour of the Argentine Republic is a national trade union centre of Argentina founded on September 27, 1930, as the result of the merge of the USA and the COA trade union centres...

created in 1968 over opposition to the collaborationist stance adopted by the general secretary of the CGT, Augusto Vandor

Augusto Vandor

Augusto Timoteo Vandor was an Argentine trade unionist leader, military and politician.-Career:Vandor was born Bovril, Entre Ríos Province, to a Dutch father and a French mother, in 1923. He enlisted in the Argentine Navy in 1940, and later became an officer in the ARA Comodoro Py warship...

) were searched and its leaders arrested. Thus, Agustín Tosco

Agustín Tosco

Agustín Gringo Tosco was an Argentine union leader, member of the CGT de los Argentinos and an important participant in the historic local uprising known as the Cordobazo.-Thought and maturity:At 27 years old, he was the general secretary for Luz y Fuerza...

, one of the main leader of the CGTA, was arrested and condemned by the War Council.

On the following days, official medias reflected the official vision of the events, allegedly a conspiracy of international communism.

Consequences

Córdoba, as well as the autonomous unions of Fiat Concord and Fiat Materfer (SITRAC-SITRAM). Workers' leaders of Córdoba, such as

Agustín Tosco

Agustín Tosco

Agustín Gringo Tosco was an Argentine union leader, member of the CGT de los Argentinos and an important participant in the historic local uprising known as the Cordobazo.-Thought and maturity:At 27 years old, he was the general secretary for Luz y Fuerza...

, René Salamanca, Gregorio Flores and José Francisco Páez, played a role on the national political stage. In Salta

Salta

Salta is a city in northwestern Argentina and the capital city of the Salta Province. Along with its metropolitan area, it has a population of 464,678 inhabitants as of the , making it Argentina's eighth largest city.-Overview:...

, Armando Jaime also headed the CGT clasista.

It also underlined two new facts in Argentine politics: on one hand, the alliance of the students' movement with the workers, and on the other hand, the predominance of the interior (or of the provinces of Argentina

Provinces of Argentina

Argentina is subdivided into twenty-three provinces and one autonomous city...

) on the capital, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

.

The Cordobazo also had lasting influences on the history of Argentina

History of Argentina

The history of Argentina is divided by historians into four main parts: the pre-Columbian time, or early history , the colonial period , the independence wars and the early post-colonial period of the nation and the history of modern Argentina .The beginning of prehistory in the present territory of...

. On one hand, it showed that the population accepted violent means to defend themselves against the military dictatorship, since no other democratic means of expression could be used. On the other hand, liberal democracy

Liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also known as constitutional democracy, is a common form of representative democracy. According to the principles of liberal democracy, elections should be free and fair, and the political process should be competitive...

, parliamentarism and the system of elections was globally refused by what came to be known as the New Opposition (Nueva Oposición). Even Arturo Frondizi

Arturo Frondizi

Arturo Frondizi Ercoli was the President of Argentina between May 1, 1958, and March 29, 1962, for the Intransigent Radical Civic Union.-Early life:Frondizi was born in Paso de los Libres, Corrientes Province...

, who had been elected in 1958, had legitimed the 1955 military coup, known as the Revolución Libertadora

Revolución Libertadora

The Revolución Libertadora was a military uprising that ended the second presidential term of Juan Perón in Argentina, on September 16, 1955.-History:...

, which had toppled Juan Perón

Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón was an Argentine military officer, and politician. Perón was three times elected as President of Argentina though he only managed to serve one full term, after serving in several government positions, including the Secretary of Labor and the Vice Presidency...

.

Henceforth, the Cordobazo showed, to contemporary activists, that they could find popular support for violent and revolutionary means of actions against Onganía's dictatorship, thus radicalizing the social and political context of Argentina. Several armed groups were formed or strengthened in the aftermaths of the Cordobazo, among them the Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas (FAP, 1967), the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación (FAL, 1968), the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo

People's Revolutionary Army (Argentina)

The Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo was the military branch of the communist Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores in Argentina...

(ERP), the Revolutionary Peronists

Peronism

Peronism , or Justicialism , is an Argentine political movement based on the programmes associated with former President Juan Perón and his second wife, Eva Perón...

Montoneros

Montoneros

Montoneros was an Argentine Peronist urban guerrilla group, active during the 1960s and 1970s. The name is an allusion to 19th century Argentinian history. After Juan Perón's return from 18 years of exile and the 1973 Ezeiza massacre, which marked the definitive split between left and right-wing...

, and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias.

Finally, the Cordobazo showed Onganía's weakness. He forced his Minister of Economy Vasena to resign, while a transition period opened itself, the military junta, supreme organ of the so-called Revolución Argentina, deciding to destitute Onganía of his leadership, replaced in June 1970 by General Roberto M. Levingston

Roberto M. Levingston

Roberto Marcelo Levingston Laborda was a general in theArgentine Army and president of Argentina from June 18, 1970 to March 22, 1971, during the Revolución Argentina period in Argentine history...

, former military attaché at the Argentine Embassy in Washington D.C.. Instead of calling for elections, Levingston decided to go ahead with the Revolución Argentina, governing against the will of the different political parties.

The latter countered Levingston's policies by the conjoint declaration of 11 November 1970, named la Hora del Pueblo (The Hour of the People), which called for free and immediate democratic elections to put an end to the political crisis. The declaration was signed by the Radical Civic Union

Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union is a political party in Argentina. The party's positions on issues range from liberal to social democratic. The UCR is a member of the Socialist International. Founded in 1891 by radical liberals, it is the oldest political party active in Argentina...

(UCR), the Justicialist Party

Justicialist Party

The Justicialist Party , or PJ, is a Peronist political party in Argentina, and the largest component of the Peronist movement.The party was led by Néstor Kirchner, President of Argentina from 2003 to 2007, until his death on October 27, 2010. The current Argentine president, Cristina Fernández de...

(Peronist Party), the Argentine Socialist Party (PSA), the Popular Conservative Party (PCP) and the Partido Bloquista (PB).

The Opposition's call for elections led to Levingston's replacement by General Alejandro Lanusse, who called for elections but excluded the Peronist Party from participating to it. Lanusse tried to implement starting in July 1971 the Gran Acuerdo Nacional (Great National Agreement), which was to find an honorable exit for the military junta without allowing Peronism participation to the elections. The proposal was rejected by Perón, exiled in Spain, who formed the FRECILINA (Frente Cívico de Liberación Nacional, Civic Front of National Liberation), headed by his delegate Héctor José Cámpora

Héctor José Cámpora

Héctor José Cámpora Demaestre was president of Argentina from 25 May until 13 July 1973.Cámpora, affectionately known as el Tío , was born in the city of Mercedes, in the Province of Buenos Aires...

and which gathered the Justicialist Party and the Movimiento de Integración y Desarrollo (MID), headed by Arturo Frondizi

Arturo Frondizi

Arturo Frondizi Ercoli was the President of Argentina between May 1, 1958, and March 29, 1962, for the Intransigent Radical Civic Union.-Early life:Frondizi was born in Paso de los Libres, Corrientes Province...

. The FRECILINA requested free and unrestricted elections, which took place on March 11, 1973.

English language

- Brennan, James : Working class protest, popular revolt, and urban insurrection in Argentina: The 1969 'Cordobazo in: Journal of social history,(1993(27)) , pp. 477–498

Spanish language

- El cordobazo : una rebelión popular, compilación e introducción: Juan Carlos Cena. Prólogo: Osvaldo Bayer, Buenos Aires : Ed. La Rosa Blindada, 2000

- En negro y blanco : Fotografías del Cordobazo al Juico a las Juntas, Idea y compilación: Pablo Cerolini. Coordinación y compilación: Alejandro Reynoso, Buenos Aires : Latingráfica, 2006

- Balvé, Beba C. ; Balvé, Beatriz S.: El '69 : huelga política de masas : rosariazo, cordobazo, rosariazo, Buenos Aires : Ed. RyR [etc.], 2005

- Brennan, James : Working class protest, popular revolt, and urban insurrection in Argentina: The 1969 'Cordobazo in: Journal of social history,(1993(27)) , pp. 477–498

- Iñigo Carrera, Nicolás: Historia y lucha de clases : el Cordobazo 30 años después in: Crítica de nuestro tiempo : revista internacional de teoría y política. - Buenos Aires , Año 8, Nr. 21, pp. 134-145

- González, Daniel: Agustín Tosco : el nombre del Cordobazo, Prólogo: Osvaldo Bayer, Buenos Aires : Capital Intelectual, 2006

- Moreno, Nahuel : Después del cordobazo, 3. ed., Buenos Aires: Ed. Antídoto, 1997

- Torres, Elpidio: El cordobazo organizado : la historia sin mitos, Buenos Aires : Ed. Catálogos, 1999

Films

- Enrique Juárez (close to the Grupo Cine LiberaciónGrupo Cine LiberaciónThe Grupo Cine Liberación was an Argentine film movement that took place during the end of the sixties. It was founded by Fernando Solanas, Octavio Getino and Gerardo Vallejo...

movement), Ya es tiempo de violencia (1969)

External links

- El Cordobazo Fragmentos del documental del periodista argentino Roberto Di Chiara, quien lo construyó a su vez con material de su archivo.

- El Cordobazo (completo) Documental completo del fragmento publicado en youtube.