Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Encyclopedia

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–53) refers to the conquest of Ireland

by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell

during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army

on behalf of England's Rump Parliament

in 1649. The conflict is sometimes referred to as the Cromwellian Wars.

Since the Irish Rebellion of 1641

, Ireland had been mainly under the control of the Irish Confederate Catholics

, who in 1649, signed an alliance with the English Royalist

party, which had been defeated in the English Civil War

. Cromwell's forces defeated the Confederate and Royalist coalition in Ireland and occupied the country - bringing to an end the Irish Confederate Wars

. He passed a series of Penal laws against Roman Catholics (the vast majority of the population) and confiscated large amounts of their land.

The Parliamentarian

reconquest of Ireland was brutal, and Cromwell is still a hated figure in Ireland. The extent to which Cromwell, who was in direct command for the first year of the campaign, is responsible for the atrocities is debated fiercely to this day. It has recently been argued by some historians that the actions of Cromwell were within the then-accepted rules of war, or were exaggerated or distorted by later propagandists; these claims have however been challenged by others.

The impact of the war on the Irish population was unquestionably severe, although there is no consensus as to the magnitude of the loss of life. Estimates of the drop in the Irish population resulting from the parliamentarian campaign vary from 15-25%, to half and even as much as five-sixths

, had several reasons for sending an army to Ireland in 1649.

, in 1649 the only remaining Parliamentarian outpost in Ireland was in Dublin, under the command of Colonel Michael Jones

. A combined Royalist

and Confederate

force under the Marquess of Ormonde

gathered at Rathmines

, south of Dublin, in order to take the city and deprive the Parliamentarians

of a port in which they could land. Jones however launched a surprise attack

on the Royalists while they were deploying on August 2, putting them to flight. Jones claimed to have killed around 4000 Royalist or Confederate soldiers and taken 2,517 prisoners.

Oliver Cromwell

called the battle, "an astonishing mercy, so great and seasonable that we are like them that dreamed", as it meant that he had a secure port at which he could land his army in Ireland, and that he retained the capital city. With Admiral Robert Blake

blockading the remaining Royalist fleet under Prince Rupert of the Rhine

in Kinsale

, Cromwell landed on August 15 with thirty five ships filled with troops and equipment. Henry Ireton landed two days later with a further seventy seven ships.

Ormonde's troops retreated from around Dublin in disarray. They were badly demoralised by their unexpected defeat at Rathmines and were incapable of fighting another pitched battle in the short term. As a result, Ormonde hoped to hold the walled towns on Ireland's east coast to hold up the Cromwellian advance until the winter, when he hoped that "Colonel Hunger and Major Sickness" (i.e. hunger and disease) would deplete their ranks.

proceeded to take the other port cities on Ireland

’s east coast, in order to secure an efficient supply of reinforcements and logistics

from England

. The first town to fall was Drogheda

, about 50 km north of Dublin. Drogheda was garrisoned by a regiment of 3000 English Royalist

and Irish Confederate soldiers, commanded by Arthur Aston

. When Cromwell’s men took the town by storm, the majority of the garrison and Catholic priests were massacred on Cromwell’s orders. Many civilians also died in the sack. Arthur Aston was beaten to death by the Roundhead

s with his own wooden leg.

The massacre of the garrison in Drogheda

, including some after they had surrendered and some who had sheltered in a Church was received with horror in Ireland, and is remembered even today as an example of Cromwell’s extreme cruelty. However, it has recently been argued (for example by Tom Reilly in Cromwell, an Honourable Enemy, Dingle 1999) that what happened at Drogheda was not unusually severe by the standards of 17th century siege warfare.

Having taken Drogheda, Cromwell sent 5000 men north under Robert Venables

to take eastern Ulster

from the remnants of a Scottish Covenanter

army that had landed there in 1642. They defeated the Scots at the battle of Lisnagarvey

and linked up with a Parliamentarian army composed of English settlers based around Derry

in western Ulster, which was commanded by Charles Coote.

The New Model Army

The New Model Army

then marched south to secure the ports of Wexford

, Waterford

and Duncannon

. Wexford was the scene of another infamous atrocity

, when Parliamentarian troops broke into the town while negotiations for its surrender were ongoing, and sacked it, killing about 2000 soldiers and 1500 townspeople and burning much of the town. Cromwell's responsibility for the sack of Wexford is disputed. He did not order the attack on the town, and had been in the process of negotiating its surrender when his troops broke into the town. On the other hand, his critics point out that he made little effort to restrain his troops or to punish them afterwards for their conduct.

Arguably, the sack of Wexford was somewhat counter-productive for the Parliamentarians. The destruction of the town meant that the Parliamentarians could not use its port as a base for supplying their forces in Ireland. Secondly, the effects of the severe measures adopted at Drogheda and at Wexford were mixed. To some degree they may have been effective in discouraging future resistance.

The Royalist commander Ormonde thought that the terror of Cromwell's army had a paralysing effect on his forces. Towns like New Ross

and Carlow

subsequently surrendered on terms when besieged by Cromwell's forces. On the other hand, the massacres of the defenders of Drogheda and Wexford prolonged resistance elsewhere, as they convinced many Irish Catholics that they would be killed even if they surrendered.

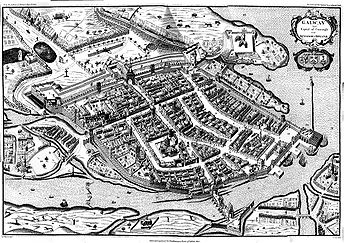

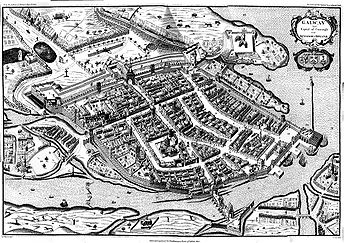

Such towns as Waterford

, Duncannon

, Clonmel

, Limerick

and Galway

only surrendered after determined resistance. Cromwell was unable to take Waterford

or Duncannon

and the New Model Army had to retire to winter quarters, where many of its men died of disease – especially typhoid and dysentery

. (The port towns of Waterford and Duncannon eventually surrendered after prolonged sieges in 1650).

The following spring, Cromwell mopped up the remaining walled towns in Ireland’s south east – notably the Confederate

The following spring, Cromwell mopped up the remaining walled towns in Ireland’s south east – notably the Confederate

Capital of Kilkenny

, which surrendered on terms. The New Model Army

met its only serious reverse in Ireland at the siege of Clonmel

, where its attacks on the towns walls were repulsed at a cost of up to 2,000 men. The town nevertheless surrendered the following day. Cromwell's behaviour at Kilkenny and Clonmel may be contrasted with his conduct at Drogheda and Wexford.

Despite the fact that his troops had suffered heavy casualties attacking the former two towns, Cromwell respected surrender terms which guaranteed the lives and property of the townspeople and the evacuation of armed Irish troops who were defending them. The change in attitude on the part of the Parliamentarian commander may have been a recognition that excessive cruelty was prolonging Irish resistance. However, in the case of Drogheda and Wexford no surrender agreement had been negotiated, and by the rules of continental siege warfare prevalent in the mid-17th century, this meant no quarter would be given; thus it can be argued that Cromwell's attitude had not changed.

Ormonde’s Royalists still held most of Munster

, but were outflanked by a mutiny of their own garrison in Cork

. The British

Protestant troops there had been fighting for the Parliament up to 1648 and resented fighting with the Irish Confederates

. Their mutiny handed Cork and most of Munster

to Cromwell

and they defeated the local Irish garrison

at the battle of Macroom

. The Irish and Royalist forces retreated behind the Shannon

river into Connaught

or (in the case of the remaining Munster forces) into the fastness of Kerry

.

repudiated his father’s (Charles I

) alliance with the Irish Confederates in preference for an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters (see Treaty of Breda (1650)

). This totally undermined Ormonde’s position as head of a Royalist coalition in Ireland. Cromwell published generous surrender terms for Protestant Royalists in Ireland and many of them either capitulated or went over to the Parliamentarian side.

This left in the field only the remaining Irish Catholic armies and a few diehard English Royalists. From this point onwards, many Irish Catholics, including their bishops and clergy, questioned why they should accept Ormonde's leadership when his master, the King had repudiated his alliance with them. Cromwell left Ireland in May 1650 to fight the Third English Civil War

against the new Scottish-Royalist alliance. He passed his command onto Henry Ireton

.

, formerly commanded by Owen Roe O'Neill

, who died in 1649. However the army was now commanded by an inexperienced Catholic Bishop named Heber MacMahon

. The Ulster army met a Parliamentarian army composed mainly of British settlers and commanded by Charles Coote at the battle of Scarrifholis

in Donegal

in June 1650. The Ulster army was routed and as many as 2000 of its men were killed. In addition, MacMahon and most of the Ulster Army's officers were either killed at the battle or captured and executed after it. This eliminated the last strong field army opposing the Parliamentarians in Ireland and secured for them the northern province of Ulster. Coote's army, despite suffering heavy losses at the Siege of Charlemont

, the last Catholic stronghold in the north, was now free to march south and invade the west coast of Ireland.

The Parliamentarians crossed the Shannon

The Parliamentarians crossed the Shannon

into the western province of Connaught

in October 1650. An Irish army under Clanricarde

had attempted to stop them but this was surprised and routed at the battle of Meelick Island

. Ormonde

was discredited by the constant stream of defeats for the Irish and Royalist forces and no longer had the confidence of the men he commanded, particularly the Irish Confederates

. He fled for France

in December 1650 and was replaced by an Irish nobleman Ulick Burke of Clanricarde as commander. The Irish and Royalist forces were penned into the area west of the river Shannon and placed their last hope on defending the strongly walled cities of Limerick

and Galway

on Ireland's west coast. These cities had built extensive modern defences and could not be taken by a straightforward assault like Drogheda or Wexford. Ireton besieged Limerick while Charles Coote surrounded Galway, but they were unable to take the strongly fortified cities and instead blockaded them until a combination of hunger and disease forced them to surrender. An Irish force from Kerry attempted to relieve Limerick from the south but this was intercepted and routed at the battle of Knocknaclashy

. Limerick fell in 1651 and Galway the following year. Disease however killed indiscriminately and Ireton along with thousands of Parliamentarian troops, died of plague

outside Limerick in 1651.

The fall of Galway

The fall of Galway

saw the end of organised resistance to the Cromwellian conquest, but fighting continued as small units of Irish troops launched guerrilla attacks

on the Parliamentarians.

The guerrilla phase of the war had been going since late 1650 and at the end of 1651, despite the defeat of the main Irish or Royalist forces, there were still estimated to be 30,000 men in arms against the Parliamentarians. Tories (from the Irish word tóraidhe meaning, "pursued man") operated from difficult terrain such as the Bog of Allen

, the Wicklow Mountains

and the drumlin

country in the north midlands, and within months, made the countryside extremely dangerous for all except large parties of Parliamentarian troops. Henry Ireton

mounted a punitive expedition

to the Wicklow mountains in 1650 to try and put down the tories there, but without success.

By early 1651, it was reported that no English supply convoys were safe if they travelled more than two miles outside a military base. In response, the Parliamentarians destroyed food supplies and forcibly evicted civilians who were thought to be helping the tories. John Hewson

systematically destroyed food stocks in counties Wicklow

and Kildare

, Hardress Waller

did likewise in the Burren

in County Clare

, as did Colonel Cook in County Wexford

. The result was famine

throughout much of Ireland, aggravated by an outbreak of bubonic plague

. As the guerrilla war ground on, the Parliamentarians, as of April 1651, designated areas such as County Wicklow

and much of the south of the country as what would now be called free-fire zones, where anyone found would be, "taken slain and destroyed as enemies and their cattle and good shall be taken or spoiled as the goods of enemies". This tactic had succeeded in the Nine Years' War

that had ended in 1603. 50,000 Irish people, including prisoners of war, were sold as indentured labourers under the English Commonwealth regime. They were sent to the English colonies of America and West Indies. In Barbados

, some of their descendants are known as Redlegs

.

This phase of the war was by far the most costly in terms of civilian loss of life. The combination of warfare, famine and plague caused a huge mortality among the Irish population. William Petty

estimated (in the Down Survey

) that the death toll of the wars in Ireland since 1641 was over 618,000 people, or about 40% of the country’s pre-war population. Of these, he estimated that over 400,000 were Catholics, 167,000 killed directly by war or famine and the remainder by war-related disease.

Eventually, the guerrilla war was ended when the Parliamentarians published surrender terms in 1652 allowing Irish troops to go abroad to serve in foreign armies not at war with the Commonwealth of England

. Most went to France or Spain. The largest Irish guerilla forces under John Fitzpatrick (in Leinster

), Edmund O'Dwyer (in Munster

) and Edmund Daly (in Connacht

) surrendered in 1652, under terms signed at Kilkenny

in May of that year. However, up to 11,000 men, mostly in Ulster

, were still thought to be in the field at the end of the year. The last Irish and Royalist forces (the remnants of the Confederate's Ulster Army, led by Philip O'Reilly) formally surrendered at Cloughoughter in County Cavan

on April 27, 1653. However, low-level guerrilla warfare continued for the remainder of the decade and was accompanied by widespread lawlessness. Undoubtedly some of the tories were simple brigands, whereas others were politically motivated. The Cromwellians distinguished in their rewards for information or capture of outlaws between "private tories" and "public tories".

religion and to punish Irish Catholics for the rebellion of 1641

, in particular the massacres of Protestant settlers in Ulster. Also he needed to raise money to pay off his army and to repay the London merchants who had subsidized the war under the Adventurers Act

back in 1640.

Anyone implicated in the rebellion of 1641

was executed. Those who participated in Confederate Ireland

had all their land confiscated and thousands were transported to the West Indies as indentured labourers. Those Catholic landowners who had not taken part in the wars still had their land confiscated, although they were entitled to claim land in Connaught

as compensation. In addition, no Catholics were allowed to live in towns. Irish soldiers who had fought in the Confederate and Royalist

armies left the country in large numbers to find service in the armies of France

and Spain

- William Petty

estimated their number at 54,000 men. The practice of Catholicism was banned and bounties were offered for the capture of priests, who were executed when found.

The Long Parliament

had passed the Adventurers Act

in 1640 (the act received royal assent in 1642), under which those who lent money to Parliament for the subjugation of Ireland would be paid in confiscated land in Ireland. In addition, Parliamentarian soldiers who served in Ireland were entitled to an allotment of confiscated land there, in lieu of their wages, which the Parliament was unable to pay in full. As a result, many thousands of New Model Army

veterans were settled in Ireland. Moreover, the pre-war Protestant settlers greatly increased their ownership of land (see also: The Cromwellian Plantation). Before the wars, Irish Catholics had owned 60% of the land in Ireland, whereas by the time of the English Restoration

, when compensations had been made to Catholic Royalists, they owned only 20% of it. During the Commonwealth period, Catholic landownership had fallen to 8%. Even after the Restoration of 1660, Catholics were barred from all public office, but not from the Irish Parliament.

. In particular, Cromwell's actions at Drogheda and Wexford earned him a reputation for cruelty.

However, pro-Cromwell accounts argue that Cromwell's actions in Ireland were not excessively cruel by the standards of the day. Cromwell himself argued that his severity when he was in Ireland applied only to "men in arms" who opposed him. Accounts of his massacres of civilians are still disputed, although there is evidence from contemporary sources that Drogheda was regarded as a massacre even then and this is the view most often taken by historians.

Formally, Cromwell's command issued in Dublin shortly after his arrival states the following:

The purpose of this order was, at least in part, to ensure that the local population would sell food and other supplies to his troops. It is worth noting that the Parliamentarian Colonel Daniel Axtell

was court-martialled by Ireton in 1650 as a result of atrocities committed by his soldiers during the Battle of Meelick Island

.

Cromwell's critics point to his response to a plea by Catholic Bishops to the Irish Catholic people to resist him in which he states that although his intention was not to "massacre, banish and destroy the Catholic inhabitants", if they did resist "I hope to be free from the misery and desolation, blood and ruin that shall befall them, and shall rejoice to exercise the utmost severity against them."

It has also recently been argued, by Tom Reilly in Cromwell, an Honourable Enemy, that what happened at Drogheda and Wexford was not unusually severe by the standards of 17th century siege warfare, in which the garrisons of towns taken by storm were routinely killed to discourage resistance in the future. The Journal History Ireland dismisses this view: "His [Reilly's] general thesis that Cromwell may well have had no moral right to take the lives at Drogheda or Wexford 'but he certainly had the law firmly on his side' does not stand up to examination." Similarly, John Morrill

commented, "A major attempt at rehabilitation was attempted by Tom Reilly, Cromwell: An Honourable Enemy (London, 1999) but this has been largely rejected by other scholars." Moreover, historians critical of Cromwell point out that even at the time the killings at Drogheda and Wexford were considered atrocities. They cite such sources as Edmund Ludlow

, the Parliamentarian commander in Ireland after Ireton's death, who wrote that the tactics used by Cromwell at Drogheda showed "extraordinary severity".

Cromwell's actions in Ireland occurred in the context of a mutually cruel war. In 1641-42 Irish insurgents in Ulster killed between 4,000 and 12,000 Protestant settlers (who had settled on land where the former Catholic owners had been evicted to make way for them) before they fled. These events were magnified in Protestant propaganda as an attempt by Irish Catholics to exterminate the English Protestant settlers in Ireland. In turn, this was used as justification by English Parliamentary and Scottish Covenant forces to take vengeance on the Irish Catholic population. A Parliamentary tract of 1655 argued that, "the whole Irish nation, consisting of gentry, clergy and commonality are engaged as one nation in this quarrel, to root out and extirpate all English Protestants from amongst them". One historian has gone so far as to say that, "It [the 1641 massacres] was to be the justification for Cromwell's genocidal campaign and settlement."

When Murrough O'Brien

, the Earl of Inchiquin and Parliamentarian commander in Cork

, at the Sack of Cashel

in 1647, slaughtered the garrison and Catholic clergy there (including Theobald Stapleton

), earning the nickname "Murrough of the Burnings". (Inchiquin switched allegiances in 1648, becoming a commander of the Royalist forces). After such battles as Dungans Hill and Scarrifholis

, English Parliamentarian forces executed their Irish Catholic prisoners. Similarly, when the Confederate Catholic general Thomas Preston

took Maynooth

in 1647, he hanged its Catholic defenders as apostates.

Seen in this light, some have argued that the severe conduct of the Parliamentarian campaign of 1649-53 appears unexceptional, given that Cromwell could not afford to fight a long campaign. Again, this is strongly disputed as was just shown above.

Nevertheless, the 1649-53 campaign remains notorious in Irish popular memory as it was responsible for a huge death toll among the Irish population. The reason for this was the counter-guerrilla tactics used by such commanders as Henry Ireton

, John Hewson

and Edmund Ludlow

against the Catholic population from 1650, when large areas of the country still resisted the Parliamentary Army. These tactics included the wholesale burning of crops, forced population movement and killing of civilians. The policy caused famine throughout the country that was "responsible for the majority of an estimated 600,000 deaths out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000."

In addition, the whole post-war Cromwellian settlement of Ireland has been characterised by historians such as Mark Levene and Alan Axelrod

as ethnic cleansing

, in that it sought to remove Irish Catholics from the eastern part of the country, others such as the historical writer Tim Pat Coogan

have described the actions of Cromwell and his subordinates as genocide. The aftermath of the Cromwellian campaign and settlement saw extensive dispossession of landowners who were Catholic, and a huge drop in population. In the event, the much larger number of surviving poorer Catholics were not moved westwards; most of them had to fend for themselves by working for the new landowners.

colonisation

of Ireland, which was merged into the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland

in 1653-59. It destroyed the native Irish Catholic land-owning classes and replaced them with colonists with a British identity. The bitterness caused by the Cromwellian settlement was a powerful source of Irish nationalism

from the 17th century onwards.

After the Stuart Restoration

in 1660, Charles II of England

restored about a third of the confiscated land to the former landlords in the Act of Settlement 1662

, but not all, as he needed political support from former parliamentarians in England. A generation later, during the Glorious Revolution

, many of the Irish Catholic landed class tried to reverse the remaining Cromwellian settlement in the Williamite war in Ireland

(1689–91), where they fought en masse for the Jacobites

. They were defeated once again, and many lost land that had been regranted after 1662. As a result, Irish and English Catholics did not become full political citizens of the British state again until 1829

and were legally barred from buying valuable interests in land until the Papists Act 1778

.

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

on behalf of England's Rump Parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

in 1649. The conflict is sometimes referred to as the Cromwellian Wars.

Since the Irish Rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

, Ireland had been mainly under the control of the Irish Confederate Catholics

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

, who in 1649, signed an alliance with the English Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

party, which had been defeated in the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

. Cromwell's forces defeated the Confederate and Royalist coalition in Ireland and occupied the country - bringing to an end the Irish Confederate Wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

. He passed a series of Penal laws against Roman Catholics (the vast majority of the population) and confiscated large amounts of their land.

The Parliamentarian

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

reconquest of Ireland was brutal, and Cromwell is still a hated figure in Ireland. The extent to which Cromwell, who was in direct command for the first year of the campaign, is responsible for the atrocities is debated fiercely to this day. It has recently been argued by some historians that the actions of Cromwell were within the then-accepted rules of war, or were exaggerated or distorted by later propagandists; these claims have however been challenged by others.

The impact of the war on the Irish population was unquestionably severe, although there is no consensus as to the magnitude of the loss of life. Estimates of the drop in the Irish population resulting from the parliamentarian campaign vary from 15-25%, to half and even as much as five-sixths

Background

The English Parliament, victorious in the English Civil WarEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, had several reasons for sending an army to Ireland in 1649.

- An alliance was signed in 1649 between the Irish Confederate CatholicsConfederate IrelandConfederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

and Charles IICharles II of EnglandCharles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

(the exiled son of the executed Charles ICharles I of EnglandCharles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

) and the English Royalists. This allowed for Royalist troops to be sent to Ireland and put the Irish Confederate Catholic troops under the command of Royalist officers led by James Butler, Earl of OrmondeJames Butler, 1st Duke of OrmondeJames Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde PC was an Irish statesman and soldier. He was the second of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom. He was the friend of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who appointeed him commander of the Cavalier forces in Ireland. From 1641 to 1647, he...

. Their aim was to invade England and restore the monarchy there. This was a threat which the new English Commonwealth could not afford to ignore. - Even if the Confederates had not allied themselves with the Royalists, it is likely that the English Parliament would have eventually tried to reconquer Ireland. They had sent Parliamentary forces to Ireland throughout the Wars of the Three KingdomsWars of the Three KingdomsThe Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

(most of them under Michael JonesMichael Jones (soldier)Lieutenant-General Michael Jones fought for King Charles I during the Irish Confederate War but joined the English Parliamentary side when the English Civil War started....

in 1647). They viewed Ireland as part of the territory governed by right by the Kingdom of EnglandKingdom of EnglandThe Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

and only temporarily out of its control since the Irish Rebellion of 1641Irish Rebellion of 1641The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

. - In addition many Parliamentarians wished to punish the Irish for atrocities against English Protestant settlers during the 1641 Uprising.

- Some Irish towns (notably WexfordWexfordWexford is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. It is situated near the southeastern corner of Ireland, close to Rosslare Europort. The town is connected to Dublin via the M11/N11 National Primary Route, and the national rail network...

and WaterfordWaterfordWaterford is a city in the South-East Region of Ireland. It is the oldest city in the country and fifth largest by population. Waterford City Council is the local government authority for the city and its immediate hinterland...

) had acted as bases from which Privateers had attacked English shipping during the 1640s. - Parliament had raised loans of £10 million under the Adventurers ActAdventurers ActThe Adventurers' Act is an Act of the Parliament of England, with the long title "An Act for the speedy and effectual reducing of the rebels in His Majesty's Kingdom of Ireland".-The main Act:...

to subdue Ireland since 1640, on the basis that its creditors would be repaid with land confiscated from Irish Catholic rebels. To repay these creditors, it would be necessary to conquer Ireland and confiscate such land. - Cromwell and many of his army were Puritans who considered all Roman Catholics to be heretics, and so for them the conquest was partly a crusade. The Irish Confederates had been supplied with arms and money by the Papacy and had welcomed the papal legatePapal legateA papal legate – from the Latin, authentic Roman title Legatus – is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic Church. He is empowered on matters of Catholic Faith and for the settlement of ecclesiastical matters....

ScarampiPierfrancesco ScarampiPierfrancesco Scarampi was a Roman Catholic oratorian and Papal envoy.-Early life and ordination:Scarampi was born into the noble Scarampi family in the Marquisate of Montferrat, today a part of Piedmont, in 1596. He was destined by his parents for the military career, but during a visit to the...

and later the Papal Nuncio RinucciniGiovanni Battista RinucciniGiovanni Battista Rinuccini was a Roman Catholic archbishop in the mid seventeenth century. He was a noted legal scholar who became chamberlain to Pope Gregory XV, who made him the Archbishop of Fermo in Italy...

in 1643-49.

The battle of Rathmines and Cromwell’s landing in Ireland

By the end of the period, known as Confederate IrelandConfederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

, in 1649 the only remaining Parliamentarian outpost in Ireland was in Dublin, under the command of Colonel Michael Jones

Michael Jones (soldier)

Lieutenant-General Michael Jones fought for King Charles I during the Irish Confederate War but joined the English Parliamentary side when the English Civil War started....

. A combined Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

and Confederate

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

force under the Marquess of Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde PC was an Irish statesman and soldier. He was the second of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom. He was the friend of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who appointeed him commander of the Cavalier forces in Ireland. From 1641 to 1647, he...

gathered at Rathmines

Rathmines

Rathmines is a suburb on the southside of Dublin, about 3 kilometres south of the city centre. It effectively begins at the south side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to the south, Ranelagh to the east and Harold's Cross to the west.Rathmines has...

, south of Dublin, in order to take the city and deprive the Parliamentarians

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

of a port in which they could land. Jones however launched a surprise attack

Battle of Rathmines

The Battle of Rathmines was fought in and around what is now the Dublin suburb of Rathmines in August 1649, during the Irish Confederate Wars, the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

on the Royalists while they were deploying on August 2, putting them to flight. Jones claimed to have killed around 4000 Royalist or Confederate soldiers and taken 2,517 prisoners.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

called the battle, "an astonishing mercy, so great and seasonable that we are like them that dreamed", as it meant that he had a secure port at which he could land his army in Ireland, and that he retained the capital city. With Admiral Robert Blake

Robert Blake (admiral)

Robert Blake was one of the most important military commanders of the Commonwealth of England and one of the most famous English admirals of the 17th century. Blake is recognised as the chief founder of England's naval supremacy, a dominance subsequently inherited by the British Royal Navy into...

blockading the remaining Royalist fleet under Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria, 1st Duke of Cumberland, 1st Earl of Holderness , commonly called Prince Rupert of the Rhine, KG, FRS was a noted soldier, admiral, scientist, sportsman, colonial governor and amateur artist during the 17th century...

in Kinsale

Kinsale

Kinsale is a town in County Cork, Ireland. Located some 25 km south of Cork City on the coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon and has a population of 2,257 which increases substantially during the summer months when the tourist season is at its peak and...

, Cromwell landed on August 15 with thirty five ships filled with troops and equipment. Henry Ireton landed two days later with a further seventy seven ships.

Ormonde's troops retreated from around Dublin in disarray. They were badly demoralised by their unexpected defeat at Rathmines and were incapable of fighting another pitched battle in the short term. As a result, Ormonde hoped to hold the walled towns on Ireland's east coast to hold up the Cromwellian advance until the winter, when he hoped that "Colonel Hunger and Major Sickness" (i.e. hunger and disease) would deplete their ranks.

The Siege of Drogheda

Upon landing, Oliver CromwellOliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

proceeded to take the other port cities on Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

’s east coast, in order to secure an efficient supply of reinforcements and logistics

Logistics

Logistics is the management of the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of destination in order to meet the requirements of customers or corporations. Logistics involves the integration of information, transportation, inventory, warehousing, material handling, and packaging, and...

from England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The first town to fall was Drogheda

Drogheda

Drogheda is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 56 km north of Dublin. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea....

, about 50 km north of Dublin. Drogheda was garrisoned by a regiment of 3000 English Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

and Irish Confederate soldiers, commanded by Arthur Aston

Arthur Aston (army officer)

Sir Arthur Aston was a lifelong professional soldier, most noted for his support for King Charles I in the English Civil War, and in folklore for the gruesome manner of his death....

. When Cromwell’s men took the town by storm, the majority of the garrison and Catholic priests were massacred on Cromwell’s orders. Many civilians also died in the sack. Arthur Aston was beaten to death by the Roundhead

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

s with his own wooden leg.

The massacre of the garrison in Drogheda

Drogheda

Drogheda is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 56 km north of Dublin. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea....

, including some after they had surrendered and some who had sheltered in a Church was received with horror in Ireland, and is remembered even today as an example of Cromwell’s extreme cruelty. However, it has recently been argued (for example by Tom Reilly in Cromwell, an Honourable Enemy, Dingle 1999) that what happened at Drogheda was not unusually severe by the standards of 17th century siege warfare.

Having taken Drogheda, Cromwell sent 5000 men north under Robert Venables

Robert Venables

Robert Venables , was a soldier during the English Civil War and noted angler.Venables was lieutenant-colonel in the parliamentary army. He was wounded at Chester in 1645. He was appointed governor of Liverpool in 1648. He served with success in Ireland from 1649 until 1654...

to take eastern Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

from the remnants of a Scottish Covenanter

Covenanter

The Covenanters were a Scottish Presbyterian movement that played an important part in the history of Scotland, and to a lesser extent in that of England and Ireland, during the 17th century...

army that had landed there in 1642. They defeated the Scots at the battle of Lisnagarvey

Battle of Lisnagarvey

The Battle of Lisnagarvey took place near Lisburn, 20 miles south of Carrickfergus, in south county Antrim, Ireland in December 1649. It was fought between the Royalists army and the Parliamentarians during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.-Background:When the army of Oliver Cromwell landed in...

and linked up with a Parliamentarian army composed of English settlers based around Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

in western Ulster, which was commanded by Charles Coote.

Wexford, Waterford and Duncannon

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

then marched south to secure the ports of Wexford

Wexford

Wexford is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. It is situated near the southeastern corner of Ireland, close to Rosslare Europort. The town is connected to Dublin via the M11/N11 National Primary Route, and the national rail network...

, Waterford

Waterford

Waterford is a city in the South-East Region of Ireland. It is the oldest city in the country and fifth largest by population. Waterford City Council is the local government authority for the city and its immediate hinterland...

and Duncannon

Duncannon

Duncannon is a village in southwest County Wexford, Ireland. Bordered to the west by Waterford harbour and sitting on a rocky promontory jutting into the channel is the strategically prominent Duncannon Fort which dominates the village.Primarily a fishing village, Duncannon also relies heavily on...

. Wexford was the scene of another infamous atrocity

Sack of Wexford

The Sack of Wexford took place in October 1649, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, when the New Model Army under Oliver Cromwell took Wexford town in south-eastern Ireland. The English Parliamentarian troops broke into the town while the commander of the garrison was trying to negotiate a...

, when Parliamentarian troops broke into the town while negotiations for its surrender were ongoing, and sacked it, killing about 2000 soldiers and 1500 townspeople and burning much of the town. Cromwell's responsibility for the sack of Wexford is disputed. He did not order the attack on the town, and had been in the process of negotiating its surrender when his troops broke into the town. On the other hand, his critics point out that he made little effort to restrain his troops or to punish them afterwards for their conduct.

Arguably, the sack of Wexford was somewhat counter-productive for the Parliamentarians. The destruction of the town meant that the Parliamentarians could not use its port as a base for supplying their forces in Ireland. Secondly, the effects of the severe measures adopted at Drogheda and at Wexford were mixed. To some degree they may have been effective in discouraging future resistance.

The Royalist commander Ormonde thought that the terror of Cromwell's army had a paralysing effect on his forces. Towns like New Ross

New Ross

New Ross is a town located in southwest County Wexford, in the southeast of Ireland. In 2006 it had a population of 7,709 people, making it the third largest town in the county after Wexford and Enniscorthy.-History:...

and Carlow

Carlow

Carlow is the county town of County Carlow in Ireland. It is situated in the south-east of Ireland, 84 km from Dublin. County Carlow is the second smallest county in Ireland by area, however Carlow Town is the 14th largest urban area in Ireland by population according to the 2006 census. The...

subsequently surrendered on terms when besieged by Cromwell's forces. On the other hand, the massacres of the defenders of Drogheda and Wexford prolonged resistance elsewhere, as they convinced many Irish Catholics that they would be killed even if they surrendered.

Such towns as Waterford

Waterford

Waterford is a city in the South-East Region of Ireland. It is the oldest city in the country and fifth largest by population. Waterford City Council is the local government authority for the city and its immediate hinterland...

, Duncannon

Duncannon

Duncannon is a village in southwest County Wexford, Ireland. Bordered to the west by Waterford harbour and sitting on a rocky promontory jutting into the channel is the strategically prominent Duncannon Fort which dominates the village.Primarily a fishing village, Duncannon also relies heavily on...

, Clonmel

Clonmel

Clonmel is the county town of South Tipperary in Ireland. It is the largest town in the county. While the borough had a population of 15,482 in 2006, another 17,008 people were in the rural hinterland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian army which sacked both...

, Limerick

Limerick

Limerick is the third largest city in the Republic of Ireland, and the principal city of County Limerick and Ireland's Mid-West Region. It is the fifth most populous city in all of Ireland. When taking the extra-municipal suburbs into account, Limerick is the third largest conurbation in the...

and Galway

Galway

Galway or City of Galway is a city in County Galway, Republic of Ireland. It is the sixth largest and the fastest-growing city in Ireland. It is also the third largest city within the Republic and the only city in the Province of Connacht. Located on the west coast of Ireland, it sits on the...

only surrendered after determined resistance. Cromwell was unable to take Waterford

Waterford

Waterford is a city in the South-East Region of Ireland. It is the oldest city in the country and fifth largest by population. Waterford City Council is the local government authority for the city and its immediate hinterland...

or Duncannon

Duncannon

Duncannon is a village in southwest County Wexford, Ireland. Bordered to the west by Waterford harbour and sitting on a rocky promontory jutting into the channel is the strategically prominent Duncannon Fort which dominates the village.Primarily a fishing village, Duncannon also relies heavily on...

and the New Model Army had to retire to winter quarters, where many of its men died of disease – especially typhoid and dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

. (The port towns of Waterford and Duncannon eventually surrendered after prolonged sieges in 1650).

Clonmel and the conquest of Munster

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

Capital of Kilkenny

Kilkenny

Kilkenny is a city and is the county town of the eponymous County Kilkenny in Ireland. It is situated on both banks of the River Nore in the province of Leinster, in the south-east of Ireland...

, which surrendered on terms. The New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

met its only serious reverse in Ireland at the siege of Clonmel

Siege of Clonmel

The Siege of Clonmel took place in April – May 1650 during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland when the town of Clonmel in County Tipperary was besieged by Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army. Cromwell's 8,000 men eventually took the town from its 2,000 Irish defenders, but not before they...

, where its attacks on the towns walls were repulsed at a cost of up to 2,000 men. The town nevertheless surrendered the following day. Cromwell's behaviour at Kilkenny and Clonmel may be contrasted with his conduct at Drogheda and Wexford.

Despite the fact that his troops had suffered heavy casualties attacking the former two towns, Cromwell respected surrender terms which guaranteed the lives and property of the townspeople and the evacuation of armed Irish troops who were defending them. The change in attitude on the part of the Parliamentarian commander may have been a recognition that excessive cruelty was prolonging Irish resistance. However, in the case of Drogheda and Wexford no surrender agreement had been negotiated, and by the rules of continental siege warfare prevalent in the mid-17th century, this meant no quarter would be given; thus it can be argued that Cromwell's attitude had not changed.

Ormonde’s Royalists still held most of Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

, but were outflanked by a mutiny of their own garrison in Cork

Cork (city)

Cork is the second largest city in the Republic of Ireland and the island of Ireland's third most populous city. It is the principal city and administrative centre of County Cork and the largest city in the province of Munster. Cork has a population of 119,418, while the addition of the suburban...

. The British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Protestant troops there had been fighting for the Parliament up to 1648 and resented fighting with the Irish Confederates

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

. Their mutiny handed Cork and most of Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

to Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

and they defeated the local Irish garrison

Garrison

Garrison is the collective term for a body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it, but now often simply using it as a home base....

at the battle of Macroom

Battle of Macroom

The Battle of Macroom was fought in 1650, near Macroom, County Cork, in southern Ireland, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. An English Parliamentarian force under Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery defeated an Irish Confederate force under David Roche....

. The Irish and Royalist forces retreated behind the Shannon

River Shannon

The River Shannon is the longest river in Ireland at . It divides the west of Ireland from the east and south . County Clare, being west of the Shannon but part of the province of Munster, is the major exception...

river into Connaught

Connacht

Connacht , formerly anglicised as Connaught, is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for...

or (in the case of the remaining Munster forces) into the fastness of Kerry

County Kerry

Kerry means the "people of Ciar" which was the name of the pre-Gaelic tribe who lived in part of the present county. The legendary founder of the tribe was Ciar, son of Fergus mac Róich. In Old Irish "Ciar" meant black or dark brown, and the word continues in use in modern Irish as an adjective...

.

The collapse of the Royalist alliance

In May 1650, Charles IICharles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

repudiated his father’s (Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

) alliance with the Irish Confederates in preference for an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters (see Treaty of Breda (1650)

Treaty of Breda (1650)

The Treaty of Breda was signed on 1 May 1650 between Charles II and the Scottish Covenanters during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.-Background:...

). This totally undermined Ormonde’s position as head of a Royalist coalition in Ireland. Cromwell published generous surrender terms for Protestant Royalists in Ireland and many of them either capitulated or went over to the Parliamentarian side.

This left in the field only the remaining Irish Catholic armies and a few diehard English Royalists. From this point onwards, many Irish Catholics, including their bishops and clergy, questioned why they should accept Ormonde's leadership when his master, the King had repudiated his alliance with them. Cromwell left Ireland in May 1650 to fight the Third English Civil War

Third English Civil War

The Third English Civil War was the last of the English Civil Wars , a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists....

against the new Scottish-Royalist alliance. He passed his command onto Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton was an English general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War. He was the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell.-Early life:...

.

Scarrifholis and the destruction of the Ulster Army

The most formidable force left to the Irish and Royalists was the 6000 strong army of UlsterUlster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, formerly commanded by Owen Roe O'Neill

Owen Roe O'Neill

Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill , anglicised as Owen Roe O'Neill , was a seventeenth century soldier and one of the most famous of the O'Neill dynasty of Ulster.- In Spanish service :...

, who died in 1649. However the army was now commanded by an inexperienced Catholic Bishop named Heber MacMahon

Heber MacMahon

Heber MacMahon was bishop of Clogher and general in Ulster. He was educated at the Irish college, Douay, and at Louvain, and ordained a Roman Catholic priest 1625. He became bishop of Clogher in 1643 and a leader among the confederate Catholics. As a general of the Ulster army he fought Oliver...

. The Ulster army met a Parliamentarian army composed mainly of British settlers and commanded by Charles Coote at the battle of Scarrifholis

Battle of Scarrifholis

The Battle of Scarrifholis was fought in Donegal North-West Ireland, on the 21st of June 1650, during the Irish Confederate Wars – part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms Cogadh ná Trí Ríocht...

in Donegal

Donegal

Donegal or Donegal Town is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. Its name, which was historically written in English as Dunnagall or Dunagall, translates from Irish as "stronghold of the foreigners" ....

in June 1650. The Ulster army was routed and as many as 2000 of its men were killed. In addition, MacMahon and most of the Ulster Army's officers were either killed at the battle or captured and executed after it. This eliminated the last strong field army opposing the Parliamentarians in Ireland and secured for them the northern province of Ulster. Coote's army, despite suffering heavy losses at the Siege of Charlemont

Siege of Charlemont

The Siege of Charlemont took place in July - August 1650 during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland when the fortress of Charlemont in County Armagh, Ireland was besieged by Charles Coote's Parliamentarian army, which was largely composed of soldiers of the New Model Army...

, the last Catholic stronghold in the north, was now free to march south and invade the west coast of Ireland.

The Sieges of Limerick and Galway

River Shannon

The River Shannon is the longest river in Ireland at . It divides the west of Ireland from the east and south . County Clare, being west of the Shannon but part of the province of Munster, is the major exception...

into the western province of Connaught

Connacht

Connacht , formerly anglicised as Connaught, is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for...

in October 1650. An Irish army under Clanricarde

Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde

Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde , was an Irish nobleman and figure in English Civil War....

had attempted to stop them but this was surprised and routed at the battle of Meelick Island

Battle of Meelick Island

The Battle of Meelick Island took place on the river Shannon, on the border between Connaught and Leinster, in Ireland in October 1650. It was fought between the armies of Confederate Ireland and the English Parliament during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The battle occurred when an English force...

. Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde PC was an Irish statesman and soldier. He was the second of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom. He was the friend of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who appointeed him commander of the Cavalier forces in Ireland. From 1641 to 1647, he...

was discredited by the constant stream of defeats for the Irish and Royalist forces and no longer had the confidence of the men he commanded, particularly the Irish Confederates

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

. He fled for France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

in December 1650 and was replaced by an Irish nobleman Ulick Burke of Clanricarde as commander. The Irish and Royalist forces were penned into the area west of the river Shannon and placed their last hope on defending the strongly walled cities of Limerick

Limerick

Limerick is the third largest city in the Republic of Ireland, and the principal city of County Limerick and Ireland's Mid-West Region. It is the fifth most populous city in all of Ireland. When taking the extra-municipal suburbs into account, Limerick is the third largest conurbation in the...

and Galway

Galway

Galway or City of Galway is a city in County Galway, Republic of Ireland. It is the sixth largest and the fastest-growing city in Ireland. It is also the third largest city within the Republic and the only city in the Province of Connacht. Located on the west coast of Ireland, it sits on the...

on Ireland's west coast. These cities had built extensive modern defences and could not be taken by a straightforward assault like Drogheda or Wexford. Ireton besieged Limerick while Charles Coote surrounded Galway, but they were unable to take the strongly fortified cities and instead blockaded them until a combination of hunger and disease forced them to surrender. An Irish force from Kerry attempted to relieve Limerick from the south but this was intercepted and routed at the battle of Knocknaclashy

Battle of Knocknaclashy

The battle of Knocknaclashy, took place in county Cork in southern Ireland in 1651. In it, an Irish Confederate force led by Donagh MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry was defeated by an English Parliamentarian force under Roger Boyle, 1st Earl of Orrery...

. Limerick fell in 1651 and Galway the following year. Disease however killed indiscriminately and Ireton along with thousands of Parliamentarian troops, died of plague

Pandemic

A pandemic is an epidemic of infectious disease that is spreading through human populations across a large region; for instance multiple continents, or even worldwide. A widespread endemic disease that is stable in terms of how many people are getting sick from it is not a pandemic...

outside Limerick in 1651.

Guerrilla warfare, famine and plague

Galway

Galway or City of Galway is a city in County Galway, Republic of Ireland. It is the sixth largest and the fastest-growing city in Ireland. It is also the third largest city within the Republic and the only city in the Province of Connacht. Located on the west coast of Ireland, it sits on the...

saw the end of organised resistance to the Cromwellian conquest, but fighting continued as small units of Irish troops launched guerrilla attacks

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

on the Parliamentarians.

The guerrilla phase of the war had been going since late 1650 and at the end of 1651, despite the defeat of the main Irish or Royalist forces, there were still estimated to be 30,000 men in arms against the Parliamentarians. Tories (from the Irish word tóraidhe meaning, "pursued man") operated from difficult terrain such as the Bog of Allen

Bog of Allen

The Bog of Allen is a large raised bog in the centre of Ireland between the rivers Liffey and Shannon.The bog's 958 square kilometers stretch into County Offaly, County Meath, County Kildare, County Laois, and County Westmeath. Peat is mechanically harvested on a large scale by Bórd na Móna,...

, the Wicklow Mountains

Wicklow Mountains

The Wicklow Mountains form the largest continuous upland area in Ireland. They occupy the whole centre of County Wicklow and stretch outside its borders into Counties Carlow, Wexford and Dublin. Where the mountains extend into County Dublin, they are known locally as the Dublin Mountains...

and the drumlin

Drumlin

A drumlin, from the Irish word droimnín , first recorded in 1833, is an elongated whale-shaped hill formed by glacial ice acting on underlying unconsolidated till or ground moraine.-Drumlin formation:...

country in the north midlands, and within months, made the countryside extremely dangerous for all except large parties of Parliamentarian troops. Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton was an English general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War. He was the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell.-Early life:...

mounted a punitive expedition

Punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a state or any group of persons outside the borders of the punishing state. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong behavior, but may be also be a covered revenge...

to the Wicklow mountains in 1650 to try and put down the tories there, but without success.

By early 1651, it was reported that no English supply convoys were safe if they travelled more than two miles outside a military base. In response, the Parliamentarians destroyed food supplies and forcibly evicted civilians who were thought to be helping the tories. John Hewson

John Hewson (regicide)

Colonel John Hewson was a soldier in the New Model Army and signed the death warrant of King Charles I, making him a regicide.-Life:...

systematically destroyed food stocks in counties Wicklow

County Wicklow

County Wicklow is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Wicklow, which derives from the Old Norse name Víkingalág or Wykynlo. Wicklow County Council is the local authority for the county...

and Kildare

County Kildare

County Kildare is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Kildare. Kildare County Council is the local authority for the county...

, Hardress Waller

Hardress Waller

Sir Hardress Waller , cousin of Sir William Waller, was an English parliamentarian of note.-Life:Born in Groombridge, Kent, and descendant of Sir Richard Waller of Groombridge Place, Waller was knighted by Charles I in 1629...

did likewise in the Burren

Burren

Burren can refer to:*The Burren, a karst landscape in County Clare, Ireland*Burren, County Down, a village in Northern Ireland*Burren College of Art, an art college in Ballyvaughan, County Clare, Ireland*Burrén and Burrena, twin hills in Aragon, Spain...

in County Clare

County Clare

-History:There was a Neolithic civilisation in the Clare area — the name of the peoples is unknown, but the Prehistoric peoples left evidence behind in the form of ancient dolmen; single-chamber megalithic tombs, usually consisting of three or more upright stones...

, as did Colonel Cook in County Wexford

County Wexford

County Wexford is a county in Ireland. It is part of the South-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Wexford. In pre-Norman times it was part of the Kingdom of Uí Cheinnselaig, whose capital was at Ferns. Wexford County Council is the local...

. The result was famine

Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including crop failure, overpopulation, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every continent in the world has...

throughout much of Ireland, aggravated by an outbreak of bubonic plague

Bubonic plague

Plague is a deadly infectious disease that is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis, named after the French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin. Primarily carried by rodents and spread to humans via fleas, the disease is notorious throughout history, due to the unrivaled scale of death...

. As the guerrilla war ground on, the Parliamentarians, as of April 1651, designated areas such as County Wicklow

County Wicklow

County Wicklow is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Wicklow, which derives from the Old Norse name Víkingalág or Wykynlo. Wicklow County Council is the local authority for the county...

and much of the south of the country as what would now be called free-fire zones, where anyone found would be, "taken slain and destroyed as enemies and their cattle and good shall be taken or spoiled as the goods of enemies". This tactic had succeeded in the Nine Years' War

Nine Years' War (Ireland)

The Nine Years' War or Tyrone's Rebellion took place in Ireland from 1594 to 1603. It was fought between the forces of Gaelic Irish chieftains Hugh O'Neill of Tír Eoghain, Hugh Roe O'Donnell of Tír Chonaill and their allies, against English rule in Ireland. The war was fought in all parts of the...

that had ended in 1603. 50,000 Irish people, including prisoners of war, were sold as indentured labourers under the English Commonwealth regime. They were sent to the English colonies of America and West Indies. In Barbados

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles. It is in length and as much as in width, amounting to . It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 kilometres east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea; therein, it is about east of the islands of Saint...

, some of their descendants are known as Redlegs

Redlegs

Redlegs is a term used to refer to the class of poor whites that live on Barbados, St. Vincent, Grenada and a few other Caribbean islands. Their forebears came from Ireland, Scotland and the West of England. Many of their ancestors were transported by Oliver Cromwell. Others had originally...

.

This phase of the war was by far the most costly in terms of civilian loss of life. The combination of warfare, famine and plague caused a huge mortality among the Irish population. William Petty

William Petty

Sir William Petty FRS was an English economist, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers...

estimated (in the Down Survey

Down Survey

The Down Survey, also known as the Civil Survey, refers to the mapping of Ireland carried out by William Petty, English scientist in 1655 and 1656....

) that the death toll of the wars in Ireland since 1641 was over 618,000 people, or about 40% of the country’s pre-war population. Of these, he estimated that over 400,000 were Catholics, 167,000 killed directly by war or famine and the remainder by war-related disease.

Eventually, the guerrilla war was ended when the Parliamentarians published surrender terms in 1652 allowing Irish troops to go abroad to serve in foreign armies not at war with the Commonwealth of England

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

. Most went to France or Spain. The largest Irish guerilla forces under John Fitzpatrick (in Leinster

Leinster

Leinster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the east of Ireland. It comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Mide, Osraige and Leinster. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the historic fifths of Leinster and Mide gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled...

), Edmund O'Dwyer (in Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

) and Edmund Daly (in Connacht

Connacht

Connacht , formerly anglicised as Connaught, is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for...

) surrendered in 1652, under terms signed at Kilkenny

Kilkenny

Kilkenny is a city and is the county town of the eponymous County Kilkenny in Ireland. It is situated on both banks of the River Nore in the province of Leinster, in the south-east of Ireland...

in May of that year. However, up to 11,000 men, mostly in Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, were still thought to be in the field at the end of the year. The last Irish and Royalist forces (the remnants of the Confederate's Ulster Army, led by Philip O'Reilly) formally surrendered at Cloughoughter in County Cavan

County Cavan

County Cavan is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Cavan. Cavan County Council is the local authority for the county...

on April 27, 1653. However, low-level guerrilla warfare continued for the remainder of the decade and was accompanied by widespread lawlessness. Undoubtedly some of the tories were simple brigands, whereas others were politically motivated. The Cromwellians distinguished in their rewards for information or capture of outlaws between "private tories" and "public tories".

The Cromwellian Settlement

Cromwell imposed an extremely harsh settlement on the Irish Catholic population. This was because of his deep religious antipathy to the CatholicCatholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

religion and to punish Irish Catholics for the rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641