Ethnic cleansing

Encyclopedia

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or

religious group from certain geographic areas.

An earlier draft by the Commission of Experts described ethnic cleansing as "the planned deliberate removal from a specific territory, persons of a particular ethnic group

, by force or intimidation, in order to render that area ethnically homogenous." which it based on "the many reports describing the policy and practices conducted in the former Yugoslavia

, 'ethnic cleansing' has been carried out by means of murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extra-judicial executions, rape and sexual assaults, confinement of civilian population in ghetto areas, forcible removal, displacement and deportation of civilian population, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, and wanton destruction of property. Those practices constitute crimes against humanity and can be assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore, such acts could also fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention".

Ethnic cleansing is not to be confused with genocide

. These terms are not synonymous, yet the academic discourse considers both as existing in a spectrum of assaults on nations or religio-ethnic groups. Ethnic cleansing is similar to forced deportation or 'population transfer' whereas genocide is the "intentional murder of part or all of a particular ethnic, religious, or national group." The idea in ethnic cleansing is "to get people to move, and the means used to this end range from the legal to the semi-legal." Some academics consider genocide as a subset of "murderous ethnic cleansing." Thus, these concepts are different, but related,

"literally and figuratively, ethnic cleansing bleeds into genocide, as mass murder is committed in order to rid the land of a people."

Synonyms include ethnic purification.

definition of ethnic cleansing is "rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation

to remove from a given area persons of another ethnic or religious group."

The term ethnic cleansing has been defined as a spectrum, or continuum by some historians. In the words of Andrew Bell-Fialkoff:

Terry Martin

has defined ethnic cleansing as "the forcible removal of an ethnically defined population from a given territory" and as "occupying the central part of a continuum between genocide on one end and nonviolent pressured ethnic emigration on the other end."

In reviewing the International Court of Justice

(ICJ) Bosnian Genocide Case in the judgement of Jorgic v. Germany on 12 July 2007 the European Court of Human Rights

quoted from the ICJ ruling on the Bosnian Genocide Case to draw a distinction between ethnic cleansing and genocide.

.

During the 1990s, the term was used extensively by the media in the former Yugoslavia

in relation to the wars in Croatia

and Bosnia. The conflicting parties used widespread and systematic acts of persecution (murder, violence, detention, intimidation) against opposing populations, creating a such coercive and frightening atmosphere that the targeted population had no option but to flee or be forcibly deported. These acts were carried out from (at least) August 1991. Croats

and Bosniaks were expelled by Serbs, Serbs and Bosniaks by Croats, and Bosniaks expelled the perceived rival populations from their domains. This period of ethnic cleansing culminated in 1995, when the long-established population of Krajina

was completely expunged. Serbs who remained, mostly elderly and helpless, were murdered by Croatian

paramilitaries.

As early as 1914, a Carnegie Endowment report on the Balkan Wars

points out that village-burning and ethnic cleansing had traditionally accompanied Balkan wars, regardless of the ethnic group in power. However, the term "cleanse" was probably used first by Vuk Karadžić, to describe what happened to the Turks

in Belgrade

when the city was captured by the Karadjordje's forces in 1806. Konstantin Nenadović wrote, in his biography of the famous Serbian leader published in 1883, that after the fighting "the Serbs

, in their bitterness (after 500 years of Turkish occupation), slit the throats of the Turks everywhere they found them, sparing neither the wounded, nor the woman, nor the Turkish children".

During World War II

, Mile Budak

laid down the Croatian plan to purge Croatia of Serbs: by killing one third, expelling one third and assimilating the rest.

On the 16th of May 1941, a commander in the Croatian extremist Ustaše

faction, Viktor Gutić, said:

Only a month later (30 June 1941), Stevan Moljević

(a lawyer from Banja Luka

who was also an ideologue of the Chetniks), published a booklet with the title "On Our State and Its Borders". Moljević asserted:

In fact, the Ustaše carried out widespread persecution and massacre of the Serbs in Croatia

during World War II

, and on several occasions used the term "cleansing" to describe these acts.

However, the concept of ethnic cleansing was not restricted to Yugoslavia during this period. The Russian

term "cleansing of borders" (ochistka granits – очистка границ), was used in Soviet Union

documents of the early 1930s to describe the forced resettlement of Polish people from the 22 km border zone

in the Byelorussian SSR

and Ukrainian SSR

. This process was repeated on an even larger and wider scale in 1939–1941, involving many other ethnicities with allegedly external loyalties: see Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

and Population transfer in the Soviet Union

.

Most notoriously, the Nazi

administration in Germany

under Adolf Hitler

applied a similar term to their systematic replacement of the Jewish people. When an area under Nazi control had its entire Jewish population removed, by driving the population out, by deportation to Concentration Camps and/or murder

, that area was declared judenrein (lit. "Jew Clean"): "cleansed of Jews" (cf. racial hygiene

).

The purpose of ethnic cleansing is to remove competitors. The party implementing this policy sees a risk (or a useful scapegoat) in a particular ethnic group, and uses propaganda

The purpose of ethnic cleansing is to remove competitors. The party implementing this policy sees a risk (or a useful scapegoat) in a particular ethnic group, and uses propaganda

about that group to stir up FUD

(fear, uncertainty and doubt) in the general population. The targeted ethnic group is marginalized and demonized. It can also be conveniently blamed for the economic, moral and political woes of that region.

Physically removing the targeted ethnic community provides a very clear, visual reminder of the power of the current government. It also provides a safety-valve for violence stirred up by the FUD. The government in power benefits significantly from seizing the assets of the dispossessed ethnic group.

The reason given for ethnic cleansing is usually that the targeted community is potentially or actually hostile to the "approved" population. Suddenly your neighbour becomes a "danger" to you and your children. In giving in to the FUD, you become as much a victim of political manipulation as the targeted group. Although ethnic cleansing has sometimes been motivated by claims that an ethnic group is literally "unclean" (as in the case of the Jews of medieval Europe

), it has generally been a deliberate (if brutal) way of ensuring the complete domination of a region.

In the 1990s Bosnian war

, ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon. It typically entailed intimidation, forced expulsion and/or killing of the undesired ethnic group, as well as the destruction or removal of key physical and cultural elements. These included places of worship, cemeteries, works of art and historic buildings. According to numerous ICTY verdicts, both Serb and Croat forces performed ethnic cleansing of their intended territories in order to create ethnically pure states (Republika Srpska

and Herzeg-Bosnia). Serb forces were also judged to have committed genocide in Srebrenica at the end of the war.

Based on the evidence of numerous attacks by Croat forces against Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks), the ICTY Trial Chamber concluded in the Kordić and Čerkez case that by April 1993, the Croat leadership from Bosnia and Herzegovina had a designated plan to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley

in Central Bosnia. Dario Kordić

, the local political leader, was found to be the instigator of this plan.

In the same year (1993), ethnic cleansing was also occurring in another country. During the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, the armed Abkhaz

separatist insurgency implemented a campaign of ethnic cleansing

against the large population of ethnic Georgians. This was actually a case of trying to drive out a majority, rather than a minority, since Georgians were the single largest ethnic group in pre-war Abkhazia, with a 45.7% plurality as of 1989. As a result of this deliberate campaign by the Abkhaz separatists, more than 250,000 ethnic Georgians were forced to flee, and approximately 30,000 people were killed during separate incidents involving massacres and expulsions (see Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia

). This was recognized as ethnic cleansing by OSCE conventions, and was also mentioned in UN General Assembly Resolution GA/10708.

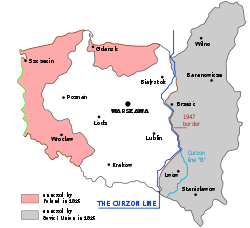

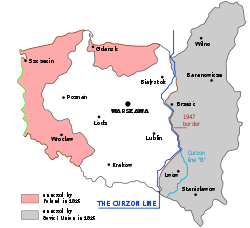

As a tactic, ethnic cleansing has a number of systemic impacts. It enables a force to eliminate civilian support for resistance by eliminating the civilians — recognizing Mao Zedong

's dictum that guerrillas among a civilian population are fish in water, it removes the fish by draining the water. When enforced as part of a political settlement, as happened with the forced resettlement of ethnic Germans to the new Germany

after 1945, it can contribute to long-term stability. Some individuals of the large German population in Czechoslovakia

and prewar Poland

had encouraged Nazi jingoism

before the Second World War, but this was forcibly resolved. It thus establishes "facts on the ground

" – radical demographic changes which can be very hard to reverse.

For the most part, ethnic cleansing is such a brutal tactic and so often accompanied by large-scale bloodshed that it is widely reviled. It is generally regarded as lying somewhere between population transfer

s and genocide

on a scale of odiousness, and is treated by international law

as a war crime

. Ethnic cleansing may be seen as a policy aimed to stabilise the borders of the State.

(ICC) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

(ICTY). The gross human-rights violations integral to stricter definitions of ethnic cleansing are treated as separate crimes falling under the definitions for genocide or crimes against humanity of the statutes.

The UN Commission of Experts (established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 780) held that the practices associated with ethnic cleansing "constitute crimes against humanity and can be assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore ... such acts could also fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention." The UN General Assembly condemned "ethnic cleansing" and racial hatred in a 1992 resolution.

There are however situations, such as the expulsion of Germans after World War II

, where ethnic cleansing has taken place without legal redress (see Preussische Treuhand v. Poland). Timothy V. Waters argues that if similar circumstances arise in the future, this precedent would allow the ethnic cleansing of other populations under international law.

. Apparently concerned with Western

media representations of atrocities committed in the conflict — which generally focused on those perpetrated by the Serbs

— atrocities committed against Serbs were dubbed "silent", on the grounds that they were not receiving adequate coverage.

Since that time, the term has been used by other ethnically oriented groups for situations that they perceive to be similar — examples include both sides in Ireland

's recent conflict

, and the expulsion of ethnic Germans

from former German territories during and after World War II

.

Some observers, however, assert that the term should only be used to denote population changes that do not occur as the result of overt violent action, or at least not from more or less organized aggression – the absence of such stressors being the very factor that makes it "silent", although some form of coercion is still used. The United States practiced this during the Indian Wars of the 19th century.

, the founder of Genocide Watch

, has criticised the rise of the term and its use for events that he feels should be called "genocide": as "ethnic cleansing" has no legal definition, its media use can detract attention from events that should be prosecuted as genocide.

religious group from certain geographic areas.

An earlier draft by the Commission of Experts described ethnic cleansing as "the planned deliberate removal from a specific territory, persons of a particular ethnic group

Ethnic group

An ethnic group is a group of people whose members identify with each other, through a common heritage, often consisting of a common language, a common culture and/or an ideology that stresses common ancestry or endogamy...

, by force or intimidation, in order to render that area ethnically homogenous." which it based on "the many reports describing the policy and practices conducted in the former Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

, 'ethnic cleansing' has been carried out by means of murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, extra-judicial executions, rape and sexual assaults, confinement of civilian population in ghetto areas, forcible removal, displacement and deportation of civilian population, deliberate military attacks or threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, and wanton destruction of property. Those practices constitute crimes against humanity and can be assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore, such acts could also fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention".

Ethnic cleansing is not to be confused with genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. These terms are not synonymous, yet the academic discourse considers both as existing in a spectrum of assaults on nations or religio-ethnic groups. Ethnic cleansing is similar to forced deportation or 'population transfer' whereas genocide is the "intentional murder of part or all of a particular ethnic, religious, or national group." The idea in ethnic cleansing is "to get people to move, and the means used to this end range from the legal to the semi-legal." Some academics consider genocide as a subset of "murderous ethnic cleansing." Thus, these concepts are different, but related,

"literally and figuratively, ethnic cleansing bleeds into genocide, as mass murder is committed in order to rid the land of a people."

Synonyms include ethnic purification.

Definitions

The official United NationsUnited Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

definition of ethnic cleansing is "rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation

Intimidation

Intimidation is intentional behavior "which would cause a person of ordinary sensibilities" fear of injury or harm. It's not necessary to prove that the behavior was so violent as to cause terror or that the victim was actually frightened.Criminal threatening is the crime of intentionally or...

to remove from a given area persons of another ethnic or religious group."

The term ethnic cleansing has been defined as a spectrum, or continuum by some historians. In the words of Andrew Bell-Fialkoff:

[E]thnic cleansing [...] defies easy definition. At one end it is virtually indistinguishable from forced emigration and population exchange while at the other it merges with deportationDeportationDeportation means the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. Today it often refers to the expulsion of foreign nationals whereas the expulsion of nationals is called banishment, exile, or penal transportation...

and genocideGenocideGenocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. At the most general level, however, ethnic cleansing can be understood as the expulsion of a population from a given territory.

Terry Martin

Terry Martin (publisher)

Terry Martin is chief executive of United Kingdom-based publishers The House of Murky Depths who publish the quarterly science fiction and horror anthology Murky Depths, and other comics and paperback books....

has defined ethnic cleansing as "the forcible removal of an ethnically defined population from a given territory" and as "occupying the central part of a continuum between genocide on one end and nonviolent pressured ethnic emigration on the other end."

In reviewing the International Court of Justice

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

(ICJ) Bosnian Genocide Case in the judgement of Jorgic v. Germany on 12 July 2007 the European Court of Human Rights

European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg is a supra-national court established by the European Convention on Human Rights and hears complaints that a contracting state has violated the human rights enshrined in the Convention and its protocols. Complaints can be brought by individuals or...

quoted from the ICJ ruling on the Bosnian Genocide Case to draw a distinction between ethnic cleansing and genocide.

The term 'ethnic cleansing' has frequently been employed to refer to the events in Bosnia and HerzegovinaBosnia and HerzegovinaBosnia and Herzegovina , sometimes called Bosnia-Herzegovina or simply Bosnia, is a country in Southern Europe, on the Balkan Peninsula. Bordered by Croatia to the north, west and south, Serbia to the east, and Montenegro to the southeast, Bosnia and Herzegovina is almost landlocked, except for the...

which are the subject of this case ... General Assembly resolution 47/121 referred in its Preamble to 'the abhorrent policy of 'ethnic cleansing', which is a form of genocide', as being carried on in Bosnia and Herzegovina. ... It [i.e. ethnic cleansing] can only be a form of genocide within the meaning of the [Genocide] ConventionConvention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of GenocideThe Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 as General Assembly Resolution 260. The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951. It defines genocide in legal terms, and is the culmination of...

, if it corresponds to or falls within one of the categories of acts prohibited by Article II of the Convention. Neither the intent, as a matter of policy, to render an area “ethnically homogeneous”, nor the operations that may be carried out to implement such policy, can as such be designated as genocide: the intent that characterizes genocide is “to destroy, in whole or in part” a particular group, and deportation or displacement of the members of a group, even if effected by force, is not necessarily equivalent to destruction of that group, nor is such destruction an automatic consequence of the displacement. This is not to say that acts described as 'ethnic cleansing' may never constitute genocide, if they are such as to be characterized as, for example, 'deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part', contrary to Article II, paragraph (c), of the Convention, provided such action is carried out with the necessary specific intent (dolus specialis), that is to say with a view to the destruction of the group, as distinct from its removal from the region. As the ICTY has observed, while 'there are obvious similarities between a genocidal policy and the policy commonly known as 'ethnic cleansing' ' (Krstić, IT-98-33-T, Trial Chamber Judgment, 2 August 2001, para. 562), yet '[a] clear distinction must be drawn between physical destruction and mere dissolution of a group. The expulsion of a group or part of a group does not in itself suffice for genocide. |ECHR quoting the ICJ.

Origins of the term

The practice is much older than the term, known throughout history. The term itself appears to have been popularised by the international media approximately early in 1992, following the discovery of Bosnian-Serb Concentration camps established in April 1992, and the subsequent assault on SarajevoSarajevo

Sarajevo |Bosnia]], surrounded by the Dinaric Alps and situated along the Miljacka River in the heart of Southeastern Europe and the Balkans....

.

During the 1990s, the term was used extensively by the media in the former Yugoslavia

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was the Yugoslav state that existed from the abolition of the Yugoslav monarchy until it was dissolved in 1992 amid the Yugoslav Wars. It was a socialist state and a federation made up of six socialist republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia,...

in relation to the wars in Croatia

Croatia

Croatia , officially the Republic of Croatia , is a unitary democratic parliamentary republic in Europe at the crossroads of the Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. Its capital and largest city is Zagreb. The country is divided into 20 counties and the city of Zagreb. Croatia covers ...

and Bosnia. The conflicting parties used widespread and systematic acts of persecution (murder, violence, detention, intimidation) against opposing populations, creating a such coercive and frightening atmosphere that the targeted population had no option but to flee or be forcibly deported. These acts were carried out from (at least) August 1991. Croats

Croats

Croats are a South Slavic ethnic group mostly living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby countries. There are around 4 million Croats living inside Croatia and up to 4.5 million throughout the rest of the world. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have...

and Bosniaks were expelled by Serbs, Serbs and Bosniaks by Croats, and Bosniaks expelled the perceived rival populations from their domains. This period of ethnic cleansing culminated in 1995, when the long-established population of Krajina

Krajina

-Etymology:In old-Croatian, this earliest geographical term appeared at least from 10th century within the Glagolitic inscriptions in Chakavian dialect, e.g. in Baška tablet about 1105, and also in some subsequent Glagolitic texts as krayna in the original medieval meaning of inlands or mainlands...

was completely expunged. Serbs who remained, mostly elderly and helpless, were murdered by Croatian

Croats

Croats are a South Slavic ethnic group mostly living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby countries. There are around 4 million Croats living inside Croatia and up to 4.5 million throughout the rest of the world. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have...

paramilitaries.

As early as 1914, a Carnegie Endowment report on the Balkan Wars

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913.By the early 20th century, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia, the countries of the Balkan League, had achieved their independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large parts of their ethnic...

points out that village-burning and ethnic cleansing had traditionally accompanied Balkan wars, regardless of the ethnic group in power. However, the term "cleanse" was probably used first by Vuk Karadžić, to describe what happened to the Turks

Turkish people

Turkish people, also known as the "Turks" , are an ethnic group primarily living in Turkey and in the former lands of the Ottoman Empire where Turkish minorities had been established in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, and Romania...

in Belgrade

Belgrade

Belgrade is the capital and largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, where the Pannonian Plain meets the Balkans. According to official results of Census 2011, the city has a population of 1,639,121. It is one of the 15 largest cities in Europe...

when the city was captured by the Karadjordje's forces in 1806. Konstantin Nenadović wrote, in his biography of the famous Serbian leader published in 1883, that after the fighting "the Serbs

Serbs

The Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

, in their bitterness (after 500 years of Turkish occupation), slit the throats of the Turks everywhere they found them, sparing neither the wounded, nor the woman, nor the Turkish children".

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Mile Budak

Mile Budak

Mile Budak was a Croatian Ustaše and writer, best known as one of the chief ideologists of the Croatian clerofascist Ustaše movement, which ruled the Independent State of Croatia, or NDH, from 1941-45 and waged a genocidal campaign against its Serb, Roma and Jewish minorities, and against Croatian...

laid down the Croatian plan to purge Croatia of Serbs: by killing one third, expelling one third and assimilating the rest.

On the 16th of May 1941, a commander in the Croatian extremist Ustaše

Ustaše

The Ustaša - Croatian Revolutionary Movement was a Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav separatist movement. The ideology of the movement was a blend of fascism, Nazism, and Croatian nationalism. The Ustaše supported the creation of a Greater Croatia that would span to the River Drina and to the border...

faction, Viktor Gutić, said:

"Every Croat who today solicits for our enemies not only is not a good Croat, but also an opponent and disrupter of the prearranged, well-calculated plan for cleansing [čišćenje] our CroatiaIndependent State of CroatiaThe Independent State of Croatia was a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, established on a part of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The NDH was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. All of Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed to NDH, together with some parts...

of unwanted elements [...]."

Only a month later (30 June 1941), Stevan Moljević

Stevan Moljevic

Dr Stevan Moljević was Serbian and Yugoslav politician, lawyer and publicist, president of the Yugoslav-French Club, president of the Yugoslav-British Club, president of Rotary International Club of Yugoslavia and member of the Central National Committee of Yugoslavia in World War II...

(a lawyer from Banja Luka

Banja Luka

-History:The name "Banja Luka" was first mentioned in a document dated February 6, 1494, but Banja Luka's history dates back to ancient times. There is a substantial evidence of the Roman presence in the region during the first few centuries A.D., including an old fort "Kastel" in the centre of...

who was also an ideologue of the Chetniks), published a booklet with the title "On Our State and Its Borders". Moljević asserted:

"One must take advantage of the war conditions and at a suitable moment seize the territory marked on the map, cleanse [očistiti] it before anybody notices and with strong battalions occupy the key places (...) and the territory surrounding these cities, freed of non-SerbSerbsThe Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

elements. The guilty must be promptly punished and the others deported – the CroatsCroatsCroats are a South Slavic ethnic group mostly living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby countries. There are around 4 million Croats living inside Croatia and up to 4.5 million throughout the rest of the world. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have...

to (significantly amputated) Croatia, the Muslims to TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

or perhaps AlbaniaAlbaniaAlbania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

– while the vacated territory is settled with Serb refugees now located in Serbia."

In fact, the Ustaše carried out widespread persecution and massacre of the Serbs in Croatia

Serbs of Croatia

Višeslav of Serbia, a contemporary of Charlemagne , ruled the Županias of Neretva, Tara, Piva, Lim, his ancestral lands. According to the Royal Frankish Annals , Duke of Pannonia Ljudevit Posavski fled, during the Frankish invasion, from his seat in Sisak to the Serbs in western Bosnia, who...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, and on several occasions used the term "cleansing" to describe these acts.

However, the concept of ethnic cleansing was not restricted to Yugoslavia during this period. The Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

term "cleansing of borders" (ochistka granits – очистка границ), was used in Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

documents of the early 1930s to describe the forced resettlement of Polish people from the 22 km border zone

Border Security Zone of Russia

The Border Security Zone in Russia is the designation of a strip of land where economic activity and access are restricted without permission of the FSB. In order to visit the zone, a permit issued by the local FSB department is required. The restricted access zone The Border Security Zone in...

in the Byelorussian SSR

Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union. It was one of the four original founding members of the Soviet Union in 1922, together with the Ukrainian SSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic...

and Ukrainian SSR

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

. This process was repeated on an even larger and wider scale in 1939–1941, involving many other ethnicities with allegedly external loyalties: see Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

Forced settlements in the Soviet Union took several forms. Though the most notorious was the Gulag labor camp system of penal labor, resettling of entire categories of population was another method of political repression implemented by the Soviet Union. At the same time, involuntary settlement...

and Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union

Population transfer in the Soviet Union may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population, often classified as "enemies of workers," deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite...

.

Most notoriously, the Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

administration in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

applied a similar term to their systematic replacement of the Jewish people. When an area under Nazi control had its entire Jewish population removed, by driving the population out, by deportation to Concentration Camps and/or murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

, that area was declared judenrein (lit. "Jew Clean"): "cleansed of Jews" (cf. racial hygiene

Racial hygiene

Racial hygiene was a set of early twentieth century state sanctioned policies by which certain groups of individuals were allowed to procreate and others not, with the expressed purpose of promoting certain characteristics deemed to be particularly desirable...

).

Ethnic cleansing as a military, political and economic tactic

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

about that group to stir up FUD

Fear, uncertainty and doubt

Fear, uncertainty and doubt, frequently abbreviated as FUD, is a tactic used in sales, marketing, public relations, politics and propaganda....

(fear, uncertainty and doubt) in the general population. The targeted ethnic group is marginalized and demonized. It can also be conveniently blamed for the economic, moral and political woes of that region.

Physically removing the targeted ethnic community provides a very clear, visual reminder of the power of the current government. It also provides a safety-valve for violence stirred up by the FUD. The government in power benefits significantly from seizing the assets of the dispossessed ethnic group.

The reason given for ethnic cleansing is usually that the targeted community is potentially or actually hostile to the "approved" population. Suddenly your neighbour becomes a "danger" to you and your children. In giving in to the FUD, you become as much a victim of political manipulation as the targeted group. Although ethnic cleansing has sometimes been motivated by claims that an ethnic group is literally "unclean" (as in the case of the Jews of medieval Europe

Jews in the Middle Ages

The history of Jews in the Middle Ages spans the timeframe of approximately 500 CE to 1750 CE. This article covers the medieval history of Jews in the Christian-dominated European region...

), it has generally been a deliberate (if brutal) way of ensuring the complete domination of a region.

In the 1990s Bosnian war

Bosnian War

The Bosnian War or the War in Bosnia and Herzegovina was an international armed conflict that took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina between April 1992 and December 1995. The war involved several sides...

, ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon. It typically entailed intimidation, forced expulsion and/or killing of the undesired ethnic group, as well as the destruction or removal of key physical and cultural elements. These included places of worship, cemeteries, works of art and historic buildings. According to numerous ICTY verdicts, both Serb and Croat forces performed ethnic cleansing of their intended territories in order to create ethnically pure states (Republika Srpska

Republika Srpska

Republika Srpska is one of two main political entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina...

and Herzeg-Bosnia). Serb forces were also judged to have committed genocide in Srebrenica at the end of the war.

Based on the evidence of numerous attacks by Croat forces against Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks), the ICTY Trial Chamber concluded in the Kordić and Čerkez case that by April 1993, the Croat leadership from Bosnia and Herzegovina had a designated plan to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley

Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing

The Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing, also known as the Lašva Valley case, refers to numerous war crimes committed during the Bosnian war by the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia's political and military leadership on Bosnian Muslim civilians in the Lašva Valley region of Bosnia-Herzegovina...

in Central Bosnia. Dario Kordić

Dario Kordic

Dario Kordić is a former Bosnian Croat politician, military commander of the HVO forces between 1992 and 1994, and vice president of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia...

, the local political leader, was found to be the instigator of this plan.

In the same year (1993), ethnic cleansing was also occurring in another country. During the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, the armed Abkhaz

Abkhazia

Abkhazia is a disputed political entity on the eastern coast of the Black Sea and the south-western flank of the Caucasus.Abkhazia considers itself an independent state, called the Republic of Abkhazia or Apsny...

separatist insurgency implemented a campaign of ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia

The Ethnic Cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia, also known as the Massacres of Georgians in Abkhazia and Genocide of Georgians in Abkhazia — refers to ethnic cleansing, massacres and forced mass expulsion of thousands of ethnic Georgians living in Abkhazia during the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict...

against the large population of ethnic Georgians. This was actually a case of trying to drive out a majority, rather than a minority, since Georgians were the single largest ethnic group in pre-war Abkhazia, with a 45.7% plurality as of 1989. As a result of this deliberate campaign by the Abkhaz separatists, more than 250,000 ethnic Georgians were forced to flee, and approximately 30,000 people were killed during separate incidents involving massacres and expulsions (see Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia

Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia

The Ethnic Cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia, also known as the Massacres of Georgians in Abkhazia and Genocide of Georgians in Abkhazia — refers to ethnic cleansing, massacres and forced mass expulsion of thousands of ethnic Georgians living in Abkhazia during the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict...

). This was recognized as ethnic cleansing by OSCE conventions, and was also mentioned in UN General Assembly Resolution GA/10708.

As a tactic, ethnic cleansing has a number of systemic impacts. It enables a force to eliminate civilian support for resistance by eliminating the civilians — recognizing Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

's dictum that guerrillas among a civilian population are fish in water, it removes the fish by draining the water. When enforced as part of a political settlement, as happened with the forced resettlement of ethnic Germans to the new Germany

Expulsion of Germans after World War II

The later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

after 1945, it can contribute to long-term stability. Some individuals of the large German population in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

and prewar Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

had encouraged Nazi jingoism

Jingoism

Jingoism is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as extreme patriotism in the form of aggressive foreign policy. In practice, it is a country's advocation of the use of threats or actual force against other countries in order to safeguard what it perceives as its national interests...

before the Second World War, but this was forcibly resolved. It thus establishes "facts on the ground

Facts on the ground

Facts on the ground is a diplomatic term that means the situation in reality as opposed to in the abstract. It originated in discussions of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, where it was used to refer to Israeli settlements built in the occupied West Bank, which were intended to establish permanent...

" – radical demographic changes which can be very hard to reverse.

For the most part, ethnic cleansing is such a brutal tactic and so often accompanied by large-scale bloodshed that it is widely reviled. It is generally regarded as lying somewhere between population transfer

Population transfer

Population transfer is the movement of a large group of people from one region to another by state policy or international authority, most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion...

s and genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

on a scale of odiousness, and is treated by international law

International law

Public international law concerns the structure and conduct of sovereign states; analogous entities, such as the Holy See; and intergovernmental organizations. To a lesser degree, international law also may affect multinational corporations and individuals, an impact increasingly evolving beyond...

as a war crime

War crime

War crimes are serious violations of the laws applicable in armed conflict giving rise to individual criminal responsibility...

. Ethnic cleansing may be seen as a policy aimed to stabilise the borders of the State.

Ethnic cleansing as a crime under international law

There is no formal legal definition of ethnic cleansing. However, ethnic cleansing in the broad sense – the forcible deportation of a population – is defined as a crime against humanity under the statutes of both International Criminal CourtInternational Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court is a permanent tribunal to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression .It came into being on 1 July 2002—the date its founding treaty, the Rome Statute of the...

(ICC) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

The International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, more commonly referred to as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia or ICTY, is a...

(ICTY). The gross human-rights violations integral to stricter definitions of ethnic cleansing are treated as separate crimes falling under the definitions for genocide or crimes against humanity of the statutes.

The UN Commission of Experts (established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 780) held that the practices associated with ethnic cleansing "constitute crimes against humanity and can be assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore ... such acts could also fall within the meaning of the Genocide Convention." The UN General Assembly condemned "ethnic cleansing" and racial hatred in a 1992 resolution.

There are however situations, such as the expulsion of Germans after World War II

Expulsion of Germans after World War II

The later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

, where ethnic cleansing has taken place without legal redress (see Preussische Treuhand v. Poland). Timothy V. Waters argues that if similar circumstances arise in the future, this precedent would allow the ethnic cleansing of other populations under international law.

Silent ethnic cleansing

Silent ethnic cleansing is a term coined in the mid-1990s by some observers of the Yugoslav warsYugoslav wars

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of wars, fought throughout the former Yugoslavia between 1991 and 1995. The wars were complex: characterized by bitter ethnic conflicts among the peoples of the former Yugoslavia, mostly between Serbs on the one side and Croats and Bosniaks on the other; but also...

. Apparently concerned with Western

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

media representations of atrocities committed in the conflict — which generally focused on those perpetrated by the Serbs

Serbs

The Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

— atrocities committed against Serbs were dubbed "silent", on the grounds that they were not receiving adequate coverage.

Since that time, the term has been used by other ethnically oriented groups for situations that they perceive to be similar — examples include both sides in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

's recent conflict

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

, and the expulsion of ethnic Germans

Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche - "German in terms of people/folk" -, defined ethnically, is a historical term from the 20th century. The words volk and volkische conveyed in Nazi thinking the meanings of "folk" and "race" while adding the sense of superior civilization and blood...

from former German territories during and after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Some observers, however, assert that the term should only be used to denote population changes that do not occur as the result of overt violent action, or at least not from more or less organized aggression – the absence of such stressors being the very factor that makes it "silent", although some form of coercion is still used. The United States practiced this during the Indian Wars of the 19th century.

Instances of ethnic cleansing

This section lists incidents that have been termed "ethnic cleansing" by some academic or legal experts. Not all experts agree on every case; nor do all the claims necessarily follow definitions given in this article. Where claims of ethnic cleansing originate from non-experts (e.g., journalists or politicians) this is noted.Early modern history

- Edward I of EnglandEdward I of EnglandEdward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

expelled all JewsJewsThe Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

living in England in 1290. Hundreds of Jewish elders were executed. - SpainSpainSpain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

expelled its JewsAlhambra decreeThe Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

in 1492, then its Muslims in 1502, forcibly Christianizing the remaining Muslim. The descendents of these converted Muslims were called Moriscos. After the 1571 suppression of the Morisco RevoltMorisco RevoltThe Morisco Revolt , also known as War of Las Alpujarras or Revolt of Las Alpujarras, in what is now Andalusia in southern Spain, was a rebellion against the Crown of Castile by the remaining Muslim converts to Christianity from the Kingdom of Granada.-The defeat of Muslim Spain:In the wake of the...

in the AlpujarrasAlpujarrasthumb|250px|A typical Alpujarran village, [[Busquístar]].La Alpujarra is a landlocked historical region in Southern Spain, which stretches south from the Sierra Nevada mountains near Granada in the autonomous community of Andalusia. The western part of the region lies in the province of Granada...

region, almost 80,000 Moriscos were expelled from there to other parts of Spain and some 270 villages and hamlets were repopulated with settlers brought in from Northern Spain. This was followed by the overall Expulsion of the MoriscosExpulsion of the MoriscosOn April 9, 1609, King Philip III of Spain decreed the Expulsion of the Moriscos . The Moriscos were the descendants of the Muslim population that converted to Christianity under threat of exile from Ferdinand and Isabella in 1502...

from the entire Spanish realm in 1609–1614. - After the Cromwellian conquest of IrelandCromwellian conquest of IrelandThe Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

and Act of SettlementAct for the Settlement of Ireland 1652The Act for the Settlement of Ireland imposed penalties including death and land confiscation against participants and bystanders of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and subsequent unrest.-Background:...

in 1652, the whole post-war Cromwellian settlement of Ireland has been characterised by historians such as Mark Levene and Alan AxelrodAlan AxelrodAlan Axelrod is an author of history, business and management. He resides in Atlanta, Georgia.He received his doctorate in English from the University of Iowa, specializing in the literature and culture of colonial America and the early republic...

as ethnic cleansing, in that it sought to remove Irish Catholics from the eastern part of the country, but others such as the historical writer Tim Pat CooganTim Pat CooganTimothy Patrick Coogan is an Irish historical writer, broadcaster and newspaper columnist. He served as editor of the Irish Press newspaper from 1968 to 1987...

have describe the actions of Cromwell and his subordinates as genocide. Most Irish remember him as the man responsible for the mass slaughter of civilians at Drogheda and Wexford and as the agent of the greatest episode of ethnic cleansing ever attempted in Western Europe as, within a decade, the percentage of land possessed by Catholics born in Ireland dropped from sixty to twenty. In a decade, the ownership of two-fifths of the land mass was transferred from several thousand Irish Catholic landowners to British Protestants. The gap between Irish and the English views of the seventeenth-century conquest remains unbridgeable and is governed by G.K. Chesterton's mirthless epigram of 1917, that "it was a tragic necessity that the Irish should remember it; but it was far more tragic that the English forgot it." - James M Lutz, Brenda J Lutz, (2004). Global Terrorism, Routledge:London, p.193: "The draconian laws applied by Oliver Cromwell in Ireland were an early version of ethnic cleansing. The Catholic Irish were to be expelled to the northwestern areas of the island. Relocation rather than extermination was the goal."

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Volume 2. ISBN 978-1-84511-057-4 Page 55, 56 & 57. A sample quote describes the Cromwellian campaign and settlement as "a conscious attempt to reduce a distinct ethnic population".

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State, I.B.Tauris: London:

[The Act of Settlement of Ireland], and the parliamentary legislation which succeeded it the following year, is the nearest thing on paper in the English, and more broadly British, domestic record, to a programme of state-sanctioned and systematic ethnic cleansing of another people. The fact that it did not include 'total' genocide in its remit, or that it failed to put into practice the vast majority of its proposed expulsions, ultimately, however, says less about the lethal determination of its makers and more about the political, structural and financial weakness of the early modern English state.

- On May 26, 1830, president Andrew JacksonAndrew JacksonAndrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

of the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

signed the Indian Removal ActIndian Removal ActThe Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

which resulted in the Trail of TearsTrail of TearsThe Trail of Tears is a name given to the forced relocation and movement of Native American nations from southeastern parts of the United States following the Indian Removal Act of 1830...

. - Michael Mann, basing his figures on those provided by Justin McCarthyJustin McCarthy (American historian)Justin A. McCarthy is an American demographer, professor of history at the University of Louisville, in Louisville, Kentucky. He holds an honorary doctorate from Boğaziçi University, Turkey, and is a board member of the Institute of Turkish Studies...

, states that between 1821 and 1922, a large number of Muslims were expelled from south-eastern Europe as Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia gained their independence from the Ottoman EmpireOttoman EmpireThe Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. Mann describes these events as "murderous ethnic cleansing on a stupendous scale not previously seen in Europe". These countries sought to expand their territory against the Ottoman EmpireOttoman EmpireThe Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, which culminated in the Balkan WarsBalkan WarsThe Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans in south-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913.By the early 20th century, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia, the countries of the Balkan League, had achieved their independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large parts of their ethnic...

of the early 20th century. - In 2005, the historian Gary Clayton AndersonGary Clayton AndersonGary Clayton Anderson is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma at Norman, Oklahoma, known for his specialization in the American Indians of the Great Plains and the Southwest.-Background:...

of the University of OklahomaUniversity of OklahomaThe University of Oklahoma is a coeducational public research university located in Norman, Oklahoma. Founded in 1890, it existed in Oklahoma Territory near Indian Territory for 17 years before the two became the state of Oklahoma. the university had 29,931 students enrolled, most located at its...

published The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1830–1875. This book repudiates traditional historians, such as Walter Prescott WebbWalter Prescott WebbWalter Prescott Webb was a 20th century U.S. historian and author noted for his groundbreaking historical work on the American West. As president of the Texas State Historical Association, he launched the project that produced the Handbook of Texas...

and Rupert N. RichardsonRupert N. RichardsonRupert Norval Richardson, Sr. , was an American historian and a former president of Baptist-affiliated Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas...

, who viewed the settlement of TexasTexasTexas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

by the displacement of the native populations as a healthful development. Anderson writes that at the time of the outbreak of the American Civil WarAmerican Civil WarThe American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, when the Texas population was nearly 600,000, the still new state was "a very violent place. ... Texans mostly blamed Indians for the violence – an unfair indictment, since a series of terrible droughts had virtually incapacitated the Plains Indians, making them incapable of extended warfare." The Conquest of Texas was nominated for a Pulitzer PrizePulitzer PrizeThe Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

. - The forced expulsion of the Acadians in 1755, from settlements in Nova ScotiaNova ScotiaNova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

, and the subsequent deaths of over 50% of the deported population, has been described by many scholars as being an act of ethnic cleansing following the French and Indian WarFrench and Indian WarThe French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

s. - The nomadic Roma people have been expelled from European countries several times.

20th century

- In December 2008 200 Turkish intellectuals and academics issued an apology for the ethnic cleansing of ArmeniansArmenian GenocideThe Armenian Genocide—also known as the Armenian Holocaust, the Armenian Massacres and, by Armenians, as the Great Crime—refers to the deliberate and systematic destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire during and just after World War I...

during World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, an event that most Western historians view as amounting to a genocideGenocideGenocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

. At a conference of Hellenes victims of ethnic cleansing, held in February 2011 in Nicosia, an apology was demanded

- The BolshevikBolshevikThe Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

regime killed or deported an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Don CossacksDon CossacksDon Cossacks were Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don.- Etymology and origins :The Don Cossack Host was a frontier military organization from the end of the 16th until the early 20th century....

during the Russian Civil WarRussian Civil WarThe Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

, in 1919–1920. Geoffrey Hosking stated "It could be argued that the Red policy towards the Don Cossacks amounted to ethnic cleansing. It was short-lived, however, and soon abandoned because it did not fit with normal Leninist theory and practice".

- The Nazi German government's persecutions and expulsions of JewsJewsThe Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

in GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, AustriaAustriaAustria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and other Nazi-controlled areas prior to the initiation of mass genocideThe HolocaustThe Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

. Estimated number of those who died in the process is nearly 6 million Jews. - In the last months of the Second World War, ethnic Germans were ethnically cleansed from Yugoslavia, Poland and Chechoslovakia, beginning in the fall of 1944 and going through the spring and summer of 1945. At the Potsdam ConferencePotsdam ConferenceThe Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

17 July-2 August 1945 the Allies agreed to transferring the rest (article XIII of the Potsdam communiqué). In all 14 million ethnic Germans were expelled and it has been asserted that as many as two million might have perished in the process. Due to horrifying revelations of Nazi genocidal practices at the same period, and to the collaboration of many ethnic Germans with Nazi occupation in various countries, their expulsion was mostly tolerated by international public opinion at the time.

- At least 330,000 SerbsSerbsThe Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

, 30,000 Jews and 30,000 Roma were killed during the NDHNDHThe letters NDH can mean:* The Independent State of Croatia * New German Hardness, or Neue Deutsche Härte * National Dairy Holdings L.P.* In ads for used vehicles, particularly aircraft: No damage history...

(see JasenovacJasenovacJasenovac is a village and a municipality in Croatian Slavonia, in the southern part of the Sisak-Moslavina county at the confluence of the river Una into Sava.The name means "ash tree" or "ash forest" in Croatian, the area being ringed by such a forest....

) (today Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina). The same number of Serbs were forced out of the NDH , from May 1941 to May 1945. The Croatian Fascist regime managed to kill more than 45 000 Serbs, 12 000 or more Jews and approximately 16 000 Roma at the Jasenovac Concentration Camp.

- During World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, in Kosovo & Metohija, approximately 10,000 Serbs were killed by Nazi German soldiersNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and Albanian colloborators., and about 80 to 100,000 or more were ethnically cleansed. After World War II, the new communist authorities of Yugoslavia banned Serbians and Montenegrins expelled during the war from returning to their abandoned estates.

- The Population exchange between Greece and TurkeyPopulation exchange between Greece and TurkeyThe 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey was based upon religious identity, and involved the Greek Orthodox citizens of Turkey and the Muslim citizens of Greece...

has been described as an ethnic cleansing.

- During the four years of wartime occupation from 1941–1944, the Axis (German, Hungarian and NDHIndependent State of CroatiaThe Independent State of Croatia was a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, established on a part of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The NDH was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. All of Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed to NDH, together with some parts...

) forces committed numerous war crimes against the civilian population of Serbs, Roma and Jews in the former Yugoslavia: about 50,000 people in VojvodinaVojvodinaVojvodina, officially called Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is an autonomous province of Serbia. Its capital and largest city is Novi Sad...

(north SerbiaSerbiaSerbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

) (see Occupation of Vojvodina, 1941–1944) were murdered and about 280,000 were arrested, raped or tortured. The total number of people killed under Hungarian occupation in Bačka was 19,573, in Banat 7,513 (under German occupation) and in Syrmia 28,199 (under Croatian occupation).

- During the Axis occupation of Albania (1943–1944), the Albanian collaborationist organization Balli KombëtarBalli KombëtarBalli Kombëtar was an Albanian nationalist, anti-communist and anti-monarchy organization established in October 1939. It was led by Ali Këlcyra and Mit’hat Frashëri...

with Nazi GermanNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

support mounted a major offensive in southern Albania (Northern EpirusNorthern EpirusNorthern Epirus is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, that are part of the modern Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek population in the region...

) with devastating results: over 200 Greek populated towns and villages were burned down or destroyed, 2,000 ethnic Greeks were killed, 5,000 imprisoned and 2,000 forced to concentration camps. Moreover, 30,000 people had to flee to nearby Greece during and after this period.

- Towards the end of World War II, nearly 30,000 ethnic Albanian Muslims were expelled from the coastal region of Epirus in northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as ChameriaChameriaChameria is a term used today mostly by Albanians for parts of the coastal region of Epirus in southern Albania and northwestern Greece It was also used by Greeks till the mid of 20th century and is frequently found in Greek literature. Today it is obsolete in Greek, surviving mainly in Greek folk...

.

- At the end of World War II, as many as 15 million ethnic Germans were expelled from eastern EuropeExpulsion of Germans after World War IIThe later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the forced migration of millions of German nationals and ethnic Germans from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria...

, following major post-war international border revisions. Historians such as Thomas Kamusella, Piotr Pikle, Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees all describe it as ethic cleansing. Kamusella he links it to the development of ethnic nationalism in central and eastern Europe.

- During the Partition of IndiaPartition of IndiaThe Partition of India was the partition of British India on the basis of religious demographics that led to the creation of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India on 14 and 15...

6 million Muslims fled genocide taking place in India to come to what became Pakistan and 5 million Hindus and Sikhs fled from what became Pakistan into India. The events which occurred during this time period have been described as ethnic cleansing by Ishtiaq Ahmed (an associate professor in the Department of Political Science, Stockholm University)

- The AzerbaijaniAzerbaijani peopleThe Azerbaijanis are a Turkic-speaking people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan, as well as in the neighbourhood states, Georgia, Russia and formerly Armenia. Commonly referred to as Azeris or Azerbaijani Turks , they also live in a wider area from the Caucasus to...

population was subjected to deportation from the territory of Democratic Republic of ArmeniaDemocratic Republic of ArmeniaThe Democratic Republic of Armenia was the first modern establishment of an Armenian state...

and Armenian SSRArmenian SSRThe Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic The Armenian Soviet...

several times during the 20th century. In the course of several Armenian-Azerbaijani conflicts, hundred of thousands of Azerbaijanis were resettled by force and many of them were killed and injured. During those same conflicts, hundreds of thousands of Armenians also were resettled by force, and many were killed and injured during pogroms which authorities ignored or encouraged.

1920s–1930s

- The Burning of 'The Negro Wall St,' also known as the 'Tulsa Race RiotTulsa Race RiotThe Tulsa race riot was a large-scale racially motivated conflict, May 31 - June 1st 1921, between the white and black communities of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which the wealthiest African-American community in the United States, the Greenwood District also known as 'The Negro Wall St' was burned to the...

': in which the wealthiest African-American community in the USA was burned to the ground. During the 16 hour offensive, over 800 people were hospitalized, more than 6,000 Greenwood DistrictGreenwood, Tulsa, OklahomaGreenwood was a district in Tulsa, Oklahoma. As one of the most successful and wealthiest African American communities in the United States during the early 20th Century, it was popularly known as America's "Black Wall Street" until the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921...

residents were arrested and detained in a prison camp, and 35 city blocks composed of 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire caused by bombing resulting in an estimated 10,000 African-American Residents left homeless. Property damage totaled $1.5 million (1921). Although the official death toll claimed that 26 blacks and 13 whites died during the fighting, most estimates are considerably higher. At the time of the riot, the American Red CrossAmerican Red CrossThe American Red Cross , also known as the American National Red Cross, is a volunteer-led, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief and education inside the United States. It is the designated U.S...

listed 8,624 persons in need of assistance, in excess of 1,000 homes and businesses destroyed, and the delivery of several stillborn infants.

- The KuomintangKuomintangThe Kuomintang of China , sometimes romanized as Guomindang via the Pinyin transcription system or GMD for short, and translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party is a founding and ruling political party of the Republic of China . Its guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People, espoused...

Chinese Muslim Generals Ma QiMa QiMa Qi was a Chinese Muslim warlord in early 20th century China.-Early life:His grandfather Sa-la Ma , is a Salar. He was born in 1869 in Daohe, now part of Linxia, Gansu, China. His father was Ma Haiyan...

and Ma BufangMa BufangMa Bufang was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the northwestern province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general...

launched extermination campaigns in QinghaiQinghaiQinghai ; Oirat Mongolian: ; ; Salar:) is a province of the People's Republic of China, named after Qinghai Lake...

and TibetTibetTibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...