The Troubles

Encyclopedia

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland

which spilled over at various times into England

, the Republic of Ireland

, and mainland Europe

. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement of 1998. , sporadic violence has nonetheless continued.

The principal issues at stake in the Troubles were the constitutional status of Northern Ireland

and the relationship between the mainly Protestant unionist

and mainly Catholic

nationalist

communities in Northern Ireland. The Troubles had both political and military (or paramilitary) dimensions. Its participants included republican

and loyalist

paramilitaries

, the security forces of the United Kingdom and of the Republic of Ireland, and nationalist and unionist politicians and political activists.

and/or Roman Catholic) and its unionist community (who mainly self-identified as British

and/or Protestant). Use of the term "the Troubles" has been raised at Northern Ireland Assembly

level, as some people considered this period of conflict to have been a war. The conflict was the result of discrimination against the Nationalist/Catholic minority by the Unionist/Protestant majority and the question of Northern Ireland's status within the United Kingdom. The violence was characterised by the armed campaigns of Irish republican

and Ulster loyalist

paramilitary groups. This included the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) campaign of 1969–1997

, intended to end British rule in Northern Ireland and to reunite Ireland

politically and thus create a new "all-Ireland" Irish Republic

; and of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), formed in 1966 in response to the perceived erosion of both the British character and unionist domination of Northern Ireland. The state security forces — the British Army

and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC) — were also involved in the violence.

The British Government's view was that its forces were neutral in the conflict, trying to uphold law and order in Northern Ireland and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to democratic self-determination. Irish republicans, however, regarded the state forces as forces of occupation and combatants in the conflict, noting collusion

between the state forces and the loyalist paramilitaries. The "Ballast" investigation by the Police Ombudsman

has confirmed that British forces, and in particular the RUC, did, on several occasions, collude with loyalist paramilitaries, were involved in murder, and did obstruct the course of justice when such claims had previously been investigated. The extent of collusion is still hotly disputed. Unionists claim that reports of collusion were either false or highly exaggerated and that there were also instances of collusion between the authorities of the Republic of Ireland and republican paramilitaries.

Alongside the violence, there was a political deadlock between the major political parties in Northern Ireland, including those who condemned violence, over the future status of Northern Ireland and the form of government there should be within Northern Ireland.

The Troubles were brought to an uneasy end by a peace process

. It included the declaration of ceasefires by most paramilitary organisations, the complete decommissioning of the IRA's weapons, the reform of the police, and the corresponding withdrawal of army troops from the streets and sensitive border areas such as South Armagh

and Fermanagh, as agreed by the signatories to the Belfast Agreement

(commonly known as the "Good Friday Agreement"). The agreement reiterated the long-held British position, which successive Irish governments had not fully acknowledged, that Northern Ireland would remain within the United Kingdom, until a majority of people in Northern Ireland voted otherwise.

On the other hand, the British Government recognised for the first time the principle that the people of the island of Ireland as a whole have the right, without any outside interference, to solve the issues between North and South by mutual consent. The latter statement was key to winning support for the agreement from nationalists and republicans. It also established a devolved power-sharing government within Northern Ireland (which had been suspended from 14 October 2002 until 8 May 2007), where the government must consist of both unionist and nationalist parties.

Though the number of active participants in the Troubles was relatively small, the Troubles touched the lives of many people in Northern Ireland on a daily basis, while occasionally spreading to the Republic of Ireland and England.

In 1609, Scottish and English settler

In 1609, Scottish and English settler

s, known as planters, were given land confiscated from the native Irish in the Plantation of Ulster

. Coupled with Protestant immigration to "unplanted" areas of Ulster, particularly Antrim and Down, this resulted in conflict between the native Catholics and the "planters". This led to two bloody ethno-religious conflicts known as the Irish Confederate Wars

(1641–1653) and the Williamite war

(1689–1691), both of which resulted in Protestant victories.

British Protestant political dominance in Ireland was ensured by the passage of the penal laws

, which curtailed the religious, legal and political rights of anyone (including both Catholics and (Protestant) Dissenters, such as Presbyterians) who did not conform to the state church—the Anglican Church of Ireland

.

As the penal laws broke down in the latter part of the eighteenth century, there was more competition for land, as restrictions were lifted on the Catholic Irish

ability to rent. With Roman Catholics allowed to buy land and enter trades from which they had formerly been banned, Protestant "Peep O'Day Boys

" attacks on that community increased. In the 1790s Catholics in south Ulster organised as "The Defenders

" and counter-attacked. This created polarisation between the communities and a dramatic reduction in reformers within the Protestant community which had been growing more receptive to ideas of democratic reform.

Following the foundation of the nationalist-based Society of the United Irishmen

by Presbyterians, Catholics and liberal Anglicans, and the resulting failed Irish Rebellion of 1798

, sectarian violence

between Catholics and Protestants continued. The Orange Order

(founded in 1795), with its stated goal of upholding the Protestant faith and loyalty to William of Orange

and his heirs, dates from this period and remains active to this day.

In 1801, a new political framework was formed with the abolition of the Irish Parliament and incorporation of Ireland into the United Kingdom

. The result was a closer tie between the former, largely pro-republican Presbyterians and Anglicans as part of a "loyal" Protestant community. Though Catholic Emancipation

was achieved in 1829, in large part by Daniel O'Connell

, largely eliminating legal discrimination against Catholics (around 75% of Ireland's population), Jews and Dissenters, O'Connell's long-term goals of Repeal of the 1801 Union and Home Rule

were never achieved. The Home Rule movement served to define the divide between most nationalists

(often Catholics), who sought the restoration of an Irish Parliament, and most unionists (often Protestants), who were afraid of being a minority in a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament and tended to support continuing union with Britain. Unionists and Home-Rule advocates countered each other during the career of Charles Stuart Parnell, a repealer, and onwards.

. In response, unionists, mostly Protestant and concentrated in Ulster, resisted both self-government and independence for Ireland, fearing for their future in an overwhelmingly Catholic country dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1912, unionists led by Edward Carson signed the Ulster Covenant

and pledged to resist Home Rule by force if necessary. To this end, they formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers and imported arms from Germany (the Easter Rising

insurrectionists did the same several years later).

Nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers

, whose ostensible goal was to oppose the Ulster Volunteers and ensure the enactment of the Third Home Rule Bill

in the event of British or unionist recalcitrance. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 temporarily averted the crisis of possible civil war and delayed the resolution of the question of Irish independence. Home Rule, though passed in the British Parliament with Royal Assent

, was suspended for the duration of the war.

Following the nationalist Easter Rising

in Dublin in 1916 by the Irish Republican Brotherhood

, and the executions of fifteen of the Rising's leaders, the separatist Sinn Féin

party won a majority of seats in Ireland and set up the First Dáil

(Irish Parliament) in Dublin. Their victory was aided by the threat of conscription to the British Army. Ireland essentially seceded from the United Kingdom. The Irish War for Independence followed, leading to eventual independence for the Republic of Ireland. In Ulster, however, and particularly in the six counties which became Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin

fared poorly in the 1918 election, and Unionists won a strong majority.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920

partitioned the island of Ireland into two separate jurisdictions, Southern Ireland

and Northern Ireland, both devolved regions of the United Kingdom. This partition of Ireland

was confirmed when the Parliament of Northern Ireland

exercised its right in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty

of 1921 to opt out of the newly established Irish Free State

.

A part of the treaty signed in 1922, stated that a boundary commission would sit in due course to decide where the frontier of the northern state would be in relation to its southern neighbour. With the two key signatories from the South of Ireland dead during the Irish Civil War

of 1922–23, this part of the treaty was given less priority by the new Southern Irish government led by Cosgrave and was quietly dropped.

The idea of the boundary commission was to include as many of the nationalist and loyalist communities in their respective states as fairly as possible. As counties Fermanagh

and Tyrone

and border areas of Londonderry

, Armagh

and Down

were mainly nationalist, the boundary commission could have rendered Northern Ireland untenable, as at best a 4 county state and possibly even smaller than this.

Northern Ireland remained a part of the United Kingdom, albeit under a separate system of government whereby it was given its own Parliament

and devolved government

. While this arrangement met the desires of unionists to remain part of the United Kingdom, nationalists largely viewed the partition of Ireland as an illegal and arbitrary division of the island against the will of the majority of its people. They argued that the Northern Ireland state was neither legitimate nor democratic, but created with a deliberately gerrymandered

unionist majority. Catholics initially composed about 33% of its population.

Northern Ireland came into being in a violent manner — a total of 557 people were killed in political or sectarian violence from 1920–1922, during and after the Irish War of Independence

. Most were Catholics. (See also; Irish War of Independence in the North East.) The result was communal strife between Catholics and Protestants, with nationalists characterising this violence, especially that in Belfast

, as a "pogrom

" against their community, although one historian argues that the reciprocity of northern violence does not fit the pogrom model or imagery so well.

A legacy of the Irish Civil War

A legacy of the Irish Civil War

, later to have a major impact on Northern Ireland, was the survival of a marginalised remnant of the Irish Republican Army

. It was illegal in both Irish states and ideologically committed to overthrowing both by force of arms to re-establish the Irish Republic

of 1919–1921. In response, the Northern Irish government passed the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) 1922

; this gave sweeping powers to the government and police to do virtually anything seen as necessary to re-establish or preserve law and order. The Act continued to be used against the nationalist community long after the violence of this period had come to an end.

The two sides' positions became strictly defined following this period. From a unionist perspective, Northern Ireland's nationalists were inherently disloyal and determined to force Protestants and unionists into a united Ireland. In the 1970s, for instance, during the period when the British government was unsuccessfully attempting to implement the Sunningdale Agreement

, then-Social Democratic and Labour Party

(SDLP) councillor Hugh Logue

described the agreement as the means by which unionists "will be trundled into a united Ireland". This threat was seen as justifying preferential treatment of unionists in housing, employment and other fields. The prevalence of large families and a more rapid population growth among Catholics was also seen as a threat.

From a nationalist perspective, continued discrimination against Catholics only proved that Northern Ireland was an inherently corrupt, British-imposed state. The Republic of Ireland Taoiseach

(Prime Minister) Charles Haughey

, whose family had fled County Londonderry

during the 1920s Troubles, described Northern Ireland as "a failed political entity". The Unionist government ignored Edward Carson's warning in 1921 that alienating Catholics would make Northern Ireland inherently unstable.

After the initial turmoil of the early 1920s, there were occasional incidents of sectarian unrest in Northern Ireland. These included a brief and ineffective IRA campaign

in the 1940s, and another abortive IRA campaign

between 1956 and 1962. By the early 1960s Northern Ireland was fairly stable.

. That month the UVF began a campaign of intimidation against a Catholic-owned off-licence on the Shankill Road. Its members painted sectarian graffiti on the neighbouring house and threw a petrol bomb through the window, killing a 77-year-old Protestant widow.

On 21 May 1966, the UVF issued a statement:

On 11 June 1966, the UVF shot and killed Catholic store owner John Patrick Scullion in west Belfast. On 26 June 1966, another UVF gun attack in west Belfast killed Catholic barman Peter Ward and seriously injured three others. On 30 March 1969 a UVF bomb exploded at an electricity station in Castlereagh, resulting in widespread black-outs. A further five bombs were exploded at electricity stations and water pipelines throughout April. It was hoped that these attacks would be blamed on the IRA, forcing moderate unionists to increase their opposition to the reforms of Terence O'Neill

's government.

On 20 June 1968, Austin Currie, a Nationalist MP staged a symbolic protest against housing discrimination when he squatted in a house in the village of Caledon, in County Tyrone, which a local Unionist party official had allocated to a Protestant 19 year old single woman over two homeless Catholic families. Catholics in Northern Ireland had long complained that religion and political views were more important than need when it came to the allocation of state-built houses and this was just one of the many unjust example of such discrimination. When the Royal Ulster Constabulary

On 20 June 1968, Austin Currie, a Nationalist MP staged a symbolic protest against housing discrimination when he squatted in a house in the village of Caledon, in County Tyrone, which a local Unionist party official had allocated to a Protestant 19 year old single woman over two homeless Catholic families. Catholics in Northern Ireland had long complained that religion and political views were more important than need when it came to the allocation of state-built houses and this was just one of the many unjust example of such discrimination. When the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC) showed up to remove Currie from the house, one of the members was the girl's brother, who would later move in with her. Prior to Currie's protest, the two Catholic families had been squatting in a nearby house but were evicted by the police, while the local news cameras filmed, when the Protestant girl, also the secretary of a Unionist parliamentary candidate, moved in to her new house. Currie had brought their grievance to the local council and Stormont

and in both cases, he was asked to leave. He then chose to highlight the issue with an act of civil disobedience which became a "cause celebre" thereby helping in rallying thousands for the first ever civil right protest march in Northern Ireland and has been referred to by some scholars as the spark which ignited the Troubles. In 1968, the marches of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

(NICRA) were met with a violent backlash by police and civil authorities. This group had launched a peaceful civil rights

campaign in 1967, which borrowed the language and symbolism of the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King in the United States. NICRA was seeking a redress of Catholic and nationalist grievances within Northern Ireland. Specifically, it wanted an end to the gerrymandering

of electoral boundaries that produced unrepresentative local councils (particularly in Derry city) by putting virtually all Catholics in a limited number of electoral wards; the abolition of the rate-payer franchise in local government elections, which gave Protestants disproportionate voting power; an end to unfair allocation of jobs and housing; and an end to the Special Powers Act

which allowed for internment

from 1971 to 1975 and other repressive measures and which was seen as being aimed at the nationalist community.

Initially, Terence O'Neill

, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, reacted favourably to this moderate-seeming campaign and promised reforms of Northern Ireland. However, he was opposed by many unionists, including William Craig and Ian Paisley

, who accused him of being a "sell-out". Some unionists immediately mistrusted the NICRA, seeing it as an IRA

"Trojan horse

".

Violence broke out at several civil rights marches when Protestant loyalists attacked civil rights demonstrators with clubs. The Royal Ulster Constabulary, almost entirely Protestant, was widely viewed by nationalists as supporting the loyalists and of allowing the violence to occur. On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march in Derry was banned by the Northern Ireland government. When civil rights activists defied the ban, they were attacked by the RUC, leading to three days of rioting. On 4 January 1969, a People's Democracy

march between Belfast and Derry through Catholic and Protestant areas was repeatedly attacked by loyalists and off-duty police. At Burntollet Bridge it was ambushed by ~200 loyalists armed with iron bars, bricks and bottles. The police did little to protect the march. Subsequently, barricades were erected in nationalist areas of Belfast and Derry to prevent police incursions. Many regard these events as the beginning of the Troubles.

This disorder culminated in the Battle of the Bogside

This disorder culminated in the Battle of the Bogside

(12 August 1969 – 14 August 1969), which was a nationalist communal uprising in Derry. The riot started as a confrontation between Catholic residents of the Bogside

, police, and members of the Apprentice Boys of Derry

who were due to march past the Bogside along the city walls.

Rioting between police and loyalists on one side and Bogside residents on the other continued for two days before British Army

troops were sent in to restore order. The "battle" sparked vicious sectarian rioting in Belfast, Newry

, Strabane

and elsewhere, starting on 14 August 1969, which left many people dead and many homes burned. The riots began with nationalist demonstrations in support of the Bogside residents and escalated when a grenade

was thrown at a police station. The RUC in response deployed three Shorland

armoured cars mounted with M2 Browning machine guns, and killed a nine-year-old boy, struck by a tracer bullet as he lay in bed in his family's flat in Divis Tower in Belfast. Loyalist crowds attacked Catholic areas, burning down much of Bombay Street, Madrid Street and other Catholic streets (see Northern Ireland riots of August 1969).

Nationalists alleged that the Royal Ulster Constabulary had aided, or at least not acted against, loyalists in these riots. The IRA was widely criticised by its supporters for failing to defend the Catholic community during the Belfast troubles of August 1969, when eight people had been killed, about 750 injured and 1,505 Catholic families had been forced out of their homes—almost five times the number of dispossessed Protestant households. Graffiti reading "IRA - I Ran Away" appeared in many areas.

In the wake of the riots, the Republic of Ireland

expressed open support for the nationalists. In a televised broadcast, Taoiseach

Jack Lynch

stated that the Irish Government could "no longer stand by" while hundreds of people were being injured. This was interpreted in some quarters as a threat of military intervention. The Irish Army

set up field hospitals along the border to provide medical support for the wounded. Under the orders of Taoiseach Lynch, the Irish Army General Staff drew up Exercise Armageddon

, a classified

plan for possible humanitarian intervention in Northern Ireland, which was ultimately rejected.

The Government of Northern Ireland

requested that the UK Government deploy the British Army in Northern Ireland

to restore order and to prevent sectarian attacks on Catholics. Nationalists initially welcomed the Army, often giving the soldiers tea and sandwiches, as they did not trust the police to act in an unbiased manner. Relations soured due to heavy-handedness by the Army.

in Northern Ireland, peaking in 1972, when nearly 500 people, just over half of them civilians, lost their lives. The year 1972 saw the greatest loss of life throughout the entire conflict.

In Derry

by the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to block access to what was known as Free Derry

; 16 of them impassable even to the British Army's one-ton armoured vehicles. Many of the nationalist/republican "no-go areas

" were controlled by one of the two factions of the Irish Republican Army—the Provisional IRA

and Official IRA.

There are several reasons why violence escalated in these years.

Unionists claim the main reason was the formation of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

(Provisional IRA), a group formed when the IRA

split into the Provisional and Official

factions. While the older IRA had embraced non-violent civil agitation, the new Provisional IRA was determined to wage "armed struggle" against British rule in Northern Ireland. The new IRA was willing to take on the role of "defenders of the Catholic community", rather than seeking working-class unity across both communities which had become the aim of the "Officials".

Nationalists pointed to a number of events in these years to explain the upsurge in violence. One such incident was the Falls Curfew

in July 1970, when 3,000 troops imposed a curfew on the nationalist Lower Falls area of Belfast, firing more than 1,500 rounds of ammunition in gun battles with the IRA and killing four people. Another was the 1971 introduction of internment without trial (out of over 350 initial detainees, none was a Protestant). Moreover, due to poor intelligence, very few of those interned were actually republican activists, but some went on to become republicans as a result of their experience. Between 1971 and 1975, 1,981 people were detained; 1,874 were Catholic/republican, while 107 were Protestant/loyalist. There were widespread allegations of abuse and even torture

of detainees, and the "five techniques

" used by the police and army for interrogation were ruled to be illegal following a British government inquiry. Nationalists also point to the fatal shootings of 14 unarmed nationalist civil rights demonstrators by the British Army in Derry on 30 January 1972, on what became known as Bloody Sunday

.

The Provisional IRA (or "Provos", as they became known), which emerged out of a split in the Irish Republican Army

in December 1969, soon established itself as defenders of the nationalist community. Despite the increasingly reformist and Marxist politics of the Official IRA, it began its own armed campaign in reaction to the ongoing violence. The Provisional IRA's offensive campaign began in early 1971 when the Army Council sanctioned attacks on the British Army.

In 1972, the Provisional IRA killed approximately 100 soldiers, wounded 500 more and carried out approximately 1,300 bombings, mostly against commercial targets which they considered "the artificial economy". The bombing campaign killed many civilians, notably on Bloody Friday

on 21 July, when 22 bombs were set off in the centre of Belfast killing seven civilians and two soldiers. The Official IRA, which had never been fully committed to armed action, called off its campaign in May 1972. Despite a temporary ceasefire in 1972 and talks with British officials, the Provisionals were determined to continue their campaign until the achievement of a united Ireland.

The loyalist paramilitaries, including the Ulster Volunteer Force and the newly-founded Ulster Defence Association

, responded to the increasing violence with a campaign of sectarian assassination of nationalists, identified simply as Catholics. Some of these killings were particularly gruesome. The Shankill Butchers

beat and tortured their victims before killing them. Another feature of the political violence was the involuntary or forced displacement of both Catholics and Protestants from formerly mixed residential areas. For example, in Belfast, Protestants were forced out of Lenadoon, and Catholics were driven out of the Rathcoole estate and the Westvale neighbourhood. In Derry city, almost all the Protestants fled to the predominantly loyalist Fountain Estate and Waterside areas.

The UK government in London, believing the Northern Ireland administration incapable of containing the security situation, sought to take over the control of law and order there. As this was unacceptable to the Northern Ireland Government, the British government pushed through emergency legislation (the Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972

) which suspended the unionist-controlled Stormont

parliament and government, and introduced "direct rule

" from London. Direct rule was initially intended as a short-term measure; the medium-term strategy was to restore self-government to Northern Ireland on a basis that was acceptable to both unionists and nationalists. Agreement proved elusive, however, and the Troubles continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s within a context of political deadlock.

The existence of "no-go areas" in Belfast and Derry was a challenge to the authority of the British government in Northern Ireland, and the British army finally demolished the barricades and re-established control over the areas in Operation Motorman

on 31 July 1972.

and a referendum in March on the status of Northern Ireland, a new parliamentary body, the Northern Ireland Assembly, was established. Elections

to this were held on 28 June. In October of that year, mainstream nationalist and unionist parties, along with the British and (Southern) Irish governments, negotiated the Sunningdale Agreement

, which was intended to produce a political settlement within Northern Ireland, but with a so-called "Irish dimension" involving the Republic of Ireland. The agreement provided for "power-sharing" between nationalists and unionists and a "Council of Ireland" designed to encourage cross-border co-operation. Seamus Mallon

, the Social Democratic and Labour Party

(SDLP) politician, has pointed to the marked similarities between the Sunningdale Agreement and the Belfast Agreement of 1998. Notably, he characterised the latter as "Sunningdale for slow learners". This assertion has been criticized by political scientists one of whom stated that "..there are... significant differences between them [Sunningdale and Belfast], both in terms of content and the circumstances surrounding their negotiation, implementation, and operation".

Unionism, however, was split over Sunningdale, which was also opposed by the IRA, whose goal remained nothing short of an end to Northern Ireland's existence as part of the United Kingdom. Many unionists opposed the concept of power-sharing, arguing that it was not feasible to share power with those (nationalists) who sought the destruction of the state. Perhaps more significant, however, was the unionist opposition to the "Irish dimension" and the Council of Ireland, which was perceived as being an all-Ireland parliament-in-waiting. The remarks by SDLP councillor Hugh Logue

to an audience at Trinity College Dublin that Sunningdale was the tool "by which the Unionists will be trundled off to a united Ireland" also damaged unionist support for the agreement.

In January 1974, Brian Faulkner

was narrowly deposed as Unionist Party leader and replaced by Harry West

. A UK general election in February 1974

gave the anti-Sunningdale unionists the opportunity to test unionist opinion with the slogan "Dublin is only a Sunningdale away", and the result galvanised their opposition: they won 11 of the 12 seats, winning 58% of the vote with most of the rest going to nationalists and pro-Sunningdale unionists.

Ultimately, however, the Sunningdale Agreement was brought down by mass action on the part of loyalists (primarily the Ulster Defence Association, at that time over 20,000 strong) and Protestant workers, who formed the Ulster Workers' Council. They organised a general strike

: the Ulster Workers' Council strike

. This severely curtailed business in Northern Ireland and cut off essential services such as water and electricity. Nationalists argue that the UK government did not do enough to break this strike and uphold the Sunningdale initiative. There is evidence that the strike was further encouraged by MI5

, a part of their campaign to 'disorientate' Wilson's government. In the event, faced with such determined opposition, the pro-Sunningdale unionists resigned from the power-sharing government and the new regime collapsed.

Three days into the UWC strike, on 17 May 1974, two UVF teams from the Belfast and Mid-Ulster

brigades detonated three no-warning car bombs

in Dublin's city centre during the Friday evening rush hour, resulting in 26 deaths and close to 300 injuries. Ninety minutes later, a fourth car bomb exploded in Monaghan

, killing another seven people. Nobody has ever been convicted of these attacks.

The failure of Sunningdale led on to the examination in London of the option of a rapid British withdrawal by the new government of Harold Wilson

. This was also considered in Dublin by Garret FitzGerald

in a memorandum of June 1975, on which he commented in 2006. This concluded that the Irish government could do little on such a withdrawal with its army of 12,500 men, with the likely result of a greater loss of life.

had lifted the proscription against the UVF in April 1974. In December, one month after the Birmingham pub bombings

which killed 21 people, the IRA declared a ceasefire; this would theoretically last throughout most of the following year. The ceasefire notwithstanding, sectarian killings actually escalated in 1975, along with internal feuding between rival paramilitary groups. This made 1975 one of the "bloodiest years of the conflict". On 31 July 1975 at Buskhill, outside Newry

, the popular Irish cabaret band "The Miami Showband

" was returning home to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge

when it was ambushed by gunmen from the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade wearing British Army uniforms at a bogus military roadside checkpoint on the main A1 road

. Three of the bandmembers were shot dead and two of the UVF men were killed when the bomb they had loaded onto the band's minibus went off prematurely. The following January, ten Protestant workers were gunned down in Kingsmill

, south County Armagh

after having been ordered off their bus by an armed Republican gang who called itself the South Armagh Republican Action Force

. These killings were in retaliation for the loyalists' double shooting attack against the Reavey and O'Dowd families

the previous night.

The violence continued through the rest of the 1970s. The British Government reinstated the ban against the UVF in October 1975, making it once more an illegal organisation. When the Provisional IRA's December 1974 ceasefire had ended in early 1976 and it had returned to violence, it had lost the hope that it had felt in the early 1970s that it could force a rapid British withdrawal from Northern Ireland, and instead developed a strategy known as the "Long War", which involved a less intense but more sustained campaign of violence that could continue indefinitely. The Official IRA

The violence continued through the rest of the 1970s. The British Government reinstated the ban against the UVF in October 1975, making it once more an illegal organisation. When the Provisional IRA's December 1974 ceasefire had ended in early 1976 and it had returned to violence, it had lost the hope that it had felt in the early 1970s that it could force a rapid British withdrawal from Northern Ireland, and instead developed a strategy known as the "Long War", which involved a less intense but more sustained campaign of violence that could continue indefinitely. The Official IRA

ceasefire of 1972, however, became permanent, and the "Official" movement eventually evolved into the Workers' Party

, which rejected violence completely. A splinter from the "Officials", however, in 1974 — the Irish National Liberation Army

— continued with a campaign of violence.

in 1976. The Peace People organised large demonstrations calling for an end to paramilitary violence. Their campaign lost momentum, however, after they appealed to the nationalist community to provide information on the IRA to security forces, the Peace People being perceived as being more critical of paramilitaries than the security forces. The decade ended with a double attack by the IRA against the British. On 27 August 1979, Lord Mountbatten of Burma

, while on holiday in Mullaghmore, County Sligo, was blown up by a bomb planted on board his boat. Three other people were also killed, including a local teenage boatman. That same afternoon, eighteen British soldiers, mostly members of the Parachute Regiment, were killed by two remote-controlled bombs at Warrenpoint

, County Down

.

Successive British Governments, having failed to achieve a political settlement, tried to "normalise" Northern Ireland. Aspects included the removal of internment

Successive British Governments, having failed to achieve a political settlement, tried to "normalise" Northern Ireland. Aspects included the removal of internment

without trial and the removal of political status for paramilitary prisoners. From 1972 onwards, paramilitaries were tried in juryless Diplock courts

to avoid intimidation of jurors. On conviction, they were to be treated as ordinary criminals. Resistance to this policy among republican prisoners led to over 500 of them in the Maze prison initiating the blanket protest

and the dirty protest

. Their protests culminated in hunger strike

s in 1980 and 1981, aimed at the restoration of political status.

In the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike

, ten republican prisoners (seven from the Provisional IRA and three from the Irish National Liberation Army

) starved themselves to death. The first hunger striker to die, Bobby Sands

, was elected to Parliament on an Anti-H-Block ticket, as was his election agent Owen Carron

following Sands' death. The hunger strikes proved emotional events for the nationalist community—over 100,000 people attended Sands' funeral mass at St. Luke's, Twinbrook, West Belfast, and crowds also attended the subsequent funerals.

From an Irish republican perspective, the significance of these events was to demonstrate a potential for political and electoral strategy. In the wake of the hunger strikes, Sinn Féin, seen by some as the Provisional IRA's political wing, began to contest elections for the first time in both Northern Ireland and the Republic. In 1986, Sinn Féin recognised the legitimacy of the Republic's Dáil, which caused a small group of republicans to break away and form Republican Sinn Féin

.

The IRA's "Long War" was boosted by large donations of arms to them from Libya

The IRA's "Long War" was boosted by large donations of arms to them from Libya

in the 1980s (see Provisional IRA arms importation

) due to Muammar al-Gaddafi

's anger at Thatcher

's government for assisting the Reagan

government's bombing of Tripoli, which had allegedly killed one of Gaddafi's children.

The IRA continued its bombing campaign. One of its most high profile actions was the Brighton hotel bombing

The IRA continued its bombing campaign. One of its most high profile actions was the Brighton hotel bombing

on 12 October 1984, when it set off a 100-pound bomb in the Grand Hotel

, Brighton, where politicians including Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher

were staying for the Conservative Party

conference. Five people were killed, including Conservative MP Sir Anthony Berry

and the wife of Government Chief Whip

John Wakeham

, and thirty-four others were injured, including Wakeham, Trade and Industry Secretary Norman Tebbit

and Tebbit's wife, Margaret.

In the mid to late 1980s loyalist paramilitaries, including the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Ulster Defence Association and Ulster Resistance

, imported arms and explosives from South Africa. The weapons obtained were divided between the UDA, the UVF and Ulster Resistance, and led to an escalation in the assassination of Catholics, although some of the weaponry (such as rocket-propelled grenades) were hardly used. These killings were in response to the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement

which gave the Irish government

a "consultative role" in the internal government of Northern Ireland.

, led since 1983 by Gerry Adams

, sought a negotiated end to the conflict, although Adams knew that this would be a very long process. In a statement, attributed to a 1970 interview with German filmmaker Teod Richter, he himself predicted that the war would last another 20 years He conducted open talks with John Hume

—the Social Democratic and Labour Party

leader—and secret talks with Government officials. Loyalists were also engaged in behind-the-scenes talks to end the violence, connecting with the British and Irish governments through Protestant clergy, in particular the Presbyterian Rev Roy Magee

and the Anglican Archbishop Robin Eames

.

The year leading up to the ceasefires was a particularly tense one, marked by atrocities. The UDA and UVF stepped up their killings of Catholics (for the first time in 1993 killing more civilians than the republicans). The IRA responded with the Shankill Road bombing

in October 1993, which aimed to kill the UDA leadership, but in fact killed nine Protestant civilians. The UDA in turn retaliated with the Greysteel massacre

and shootings at Castlerock, County Londonderry.

On 16 June 1994, just before the ceasefires, the Irish National Liberation Army killed a UVF member in a gun attack on the Shankill Road. In revenge, three days later, the UVF killed six civilians in a shooting at a pub in Loughinisland, County Down

. The IRA, in the remaining month before its ceasefire, killed four senior loyalists, three from the UDA and one from the UVF. There are various interpretations of the spike in violence before the ceasefires. One theory is that the loyalists feared the peace process represented an imminent "sellout" of the Union and ratcheted up their violence accordingly. Another explanation is that the republicans were "settling old scores" before the end of their campaigns. They wanted to enter the political process from a position of military strength rather than weakness.

On 31 August 1994, the Provisional IRA declared a ceasefire

. The loyalist paramilitaries, temporarily united in the "Combined Loyalist Military Command

", reciprocated six weeks later. Although these ceasefires failed in the short run, they marked an effective end to large-scale political violence in the Troubles, as they paved the way for the final ceasefire.

In 1995 the United States appointed George Mitchell as the United States Special Envoy for Northern Ireland

. Mitchell was recognised as being more than a token envoy and someone representing a President (Bill Clinton

) with a deep interest in events. The British and Irish governments agreed that Mitchell would chair an international commission on disarmament of paramilitary groups.

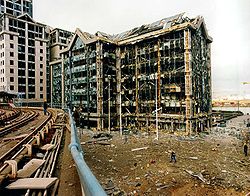

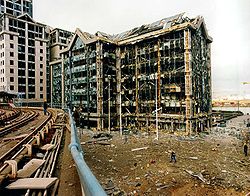

The attack was followed by several more, most notably the Manchester Bombing

The attack was followed by several more, most notably the Manchester Bombing

, which destroyed a large area of the centre of the city on 15 June 1996. It was the largest bomb attack in Britain since World War II. While the attack avoided any fatalities due to the rapid response of the emergency services to a telephone warning, over 200 people were injured in the attack, many of them outside the established cordon. The damage caused by the blast was valued at £411 million. The last British soldier to die in the Troubles, Lance Bombardier Stephen Restorick, was also killed during this period, on 12 February 1997, by the "South Armagh sniper".

The IRA reinstated their ceasefire in July 1997, as negotiations for the document that would become known as the Good Friday Agreement were starting without Sinn Féin. In September of the same year Sinn Féin signed the Mitchell Principles

and was invited into the talks.

The UVF was the first paramilitary grouping to split as a result of their ceasefire, spawning the Loyalist Volunteer Force

(LVF) in 1996. In December 1997, the INLA assassinated LVF leader Billy Wright

, leading to a series of revenge killings of Catholics by loyalist groups. In addition, a group of Republicans split from the Provisional IRA and formed the Real IRA.

In August 1998, a Real IRA bomb

in Omagh

killed 29 civilians. This bombing largely discredited "dissident" Republicans and their campaigns in the eyes of most nationalists. They became small groups with little influence, but still capable of violence. The INLA also declared a ceasefire after the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

Since then, most paramilitary violence has been directed inwards, at their "own" communities and at other factions within their organisations. The UDA, for example, has feuded with their fellow loyalists the UVF on two occasions since 2000. There have also been internal struggles for power between "Brigade commanders" and involvement in organised crime.

Provisional IRA members have also been accused of killing men, such as Robert McCartney, Matthew Ignatius Burns and Andrew Kearney.

of 1998. This Agreement restored self-government to Northern Ireland on the basis of "power-sharing". In 1999, an executive was formed consisting of the four main parties, including Sinn Féin. Other important changes included the reform of the RUC, renamed as the Police Service of Northern Ireland

, which was required to recruit at least a minimum quota of Catholics, and the abolition of Diplock courts

under the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act 2007. A security normalisation process also began as part of the treaty, which comprised the progressive closing of redundant Army barracks, border observation towers, and the withdrawal of all forces taking part in Operation Banner

- including the resident battalions of the Royal Irish Regiment

- that would be replaced by an infantry brigade, deployed in ten sites around Northern Ireland but with no operative role in the province itself.

The power-sharing Executive and Assembly were suspended in 2002, when unionists withdrew following the exposure of a Provisional IRA spy ring within the Sinn Féin office. There were ongoing tensions about the Provisional IRA's failure to disarm fully and sufficiently quickly. IRA decommissioning has since been completed (in September 2005) to the satisfaction of most.

A feature of Northern Irish politics since the Agreement has been the eclipse in electoral terms of parties such as the Social Democratic and Labour Party and Ulster Unionist Party

, by rival parties such as Sinn Féin and the DUP. Similarly, although political violence is greatly reduced, sectarian animosity has not disappeared. Residential areas are more segregated between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists than ever.

Because of this, progress towards restoring the power-sharing institutions was slow and tortuous. On 8 May 2007, devolved government returned to Northern Ireland. DUP leader Ian Paisley

and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness

took office as First Minister and deputy First Minister, respectively.

The Group stated its terms of reference as:

The group was co-chaired by His Grace the Most Rev. Dr. Robin Eames

(Lord Eames), the former Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh, and Denis Bradley

, and published its report in January 2009.

Whilst the group met MI5

and the UVF, the Provisional IRA refused to meet with the group.

The Group published its recommendations on 28 January 2009 in a 190-page report, containing more than 30 recommendations, expected to cost in total £300m. The report recommended the setting up of a 5 year Legacy Commission, a Reconciliation Forum to aid the existing commission for victims and survivors, and a new historical case review body. The report concluded the Legacy Commission should make proposals on how "a line might be drawn", but omitted proposals for an amnesty. Additionally, it was proposed that no new Public Inquiries be held, and an annual Day of Reflection and Reconciliation and a shared memorial to the conflict. A controversial proposal to pay the relatives of all victims killed in The Troubles, including the families of paramilitary members, £12,000, as a "recognition payment", caused disruption to the report's launch by protestors. This estimated cost of this part of the proposal was £40m.

between the state security forces and loyalist paramilitaries as highlighted by the Stevens Inquiries and the case of Brian Nelson amongst others.

According to a report released by the Irish government in 2006, members of British security forces colluded with loyalist paramilitaries in a number of attacks during the troubles.

One problem, highlighted by documents declassified in 2004, is that British government documents from the early 1970s show overlapping membership between the Ulster Defence Regiment

One problem, highlighted by documents declassified in 2004, is that British government documents from the early 1970s show overlapping membership between the Ulster Defence Regiment

(UDR) and loyalist paramilitary groups. The documents include a report titled "Subversion in the UDR" which details the problem. The documents state that:

Despite knowing that the UDR had problems and that over 200 weapons had been passed from British Army hands to loyalist paramilitaries by 1973, the British Government went on to increase the role of the UDR in maintaining order in Northern Ireland.

" carried out a string of sectarian attacks against the Irish Catholic and nationalist community in the area of mid-Ulster known as the "murder triangle". The gang included members of an RUC "anti-terrorist" unit called the Special Patrol Group

, members of the UDR, and members of the UVF. In 1980 two SPG members, John Weir

and Billy McCaughey

, were convicted of murder for a 1977 attack on a Keady

, and the 1978 kidnap of a Catholic priest. They implicated their immediate colleagues in at least 11 other killings and alleged that they were part of a wider conspiracy involving RUC Special Branch, British military intelligence, and the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade (which was commanded by Robin "The Jackal" Jackson

from July 1975 to the early 1990s). The nationalist Pat Finucane Centre

has attributed 87 killings to the gang; including the Dublin and Monaghan bombings

of 1974, the Miami Showband killings

of 1975, and the Reavey and O'Dowd killings

of 1976. The Special Patrol Group was disbanded by the RUC after the men's conviction in 1980.

Elements within the Army and police have been shown to have leaked intelligence to loyalists from the late 1980s to target republican activists. In 1992, a British agent within the UDA, Brian Nelson, revealed Army complicity in his activities which included killings and importing arms. Factions within the British Army and RUC are known to have cooperated with Nelson and the UDA through the British Army Intelligence group called the Force Research Unit

Elements within the Army and police have been shown to have leaked intelligence to loyalists from the late 1980s to target republican activists. In 1992, a British agent within the UDA, Brian Nelson, revealed Army complicity in his activities which included killings and importing arms. Factions within the British Army and RUC are known to have cooperated with Nelson and the UDA through the British Army Intelligence group called the Force Research Unit

. Since the late 1990s, some loyalists have confirmed to journalists such as Peter Taylor

that they received files and intelligence from security sources on Republican targets.

In a report released on 22 January 2007, the Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan

stated that UVF informers committed serious crimes, including murder, with the full knowledge of their handlers. The report alleged that certain Special Branch

officers created false statements, blocked evidence searches and "baby-sat" suspects during interviews. Democratic Unionist Party

(DUP) councillor and former Police Federation chairman Jimmy Spratt said if the report "had had one shred of credible evidence then we could have expected charges against former police officers. There are no charges, so the public should draw their own conclusion, the report is clearly based on little fact". However, the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

, Peter Hain

, said that he was "convinced that at least one prosecution will arise out of today's report". Peter Hain also said, "There are all sorts of opportunities for prosecutions to follow. The fact that some retired police officers obstructed the investigation and refused to co-operate with the Police Ombudsman is very serious in itself. There will be consequences for those involved and it is a matter for the relevant bodies to take up".

rather than arresting IRA suspects. The security forces denied this and point out that in incidents such as the killing of eight IRA men at Loughgall

in 1987, the paramilitaries who were killed were heavily armed. Others argue that incidents such as the shooting of three unarmed IRA members

in Gibraltar

by the Special Air Service

ten months later confirmed suspicions among republicans, and in the British and Irish media, of a tacit British shoot-to-kill policy of suspected IRA members.

parades take place across Northern Ireland. The parades are held to commemorate William of Orange

's victory in the Battle of the Boyne

in 1690, which secured the Protestant Ascendancy

and British rule in Ireland. One particular flashpoint that has caused repeated strife is the Garvaghy Road area in Portadown

, where an Orange parade from Drumcree Church

passes through a mainly nationalist estate off the Garvaghy Road. This parade has now been banned indefinitely, following nationalist riots against the parade, and also loyalist counter-riots against its banning. In 1995, 1996 and 1997, there were several weeks of prolonged rioting throughout Northern Ireland over the impasse at Drumcree. A number of people died in this violence, including a Catholic taxi driver, killed by the Loyalist Volunteer Force

, and three (of four) nominally Catholic brothers (from a mixed-religion family) died when their house in Ballymoney

was petrol-bombed.

Disputes have also occurred in Belfast over parade routes along the Ormeau and Crumlin Roads. Orangemen hold that to march their "traditional route" is their civil right. Nationalists argue that, by parading through predominantly Catholic areas, the Orange Order is being unnecessarily provocative. Symbolically, the ability to either parade or to block a parade is viewed as expressing ownership of "territory" and influence over the government of Northern Ireland.

Many commentators have expressed the view that the violence over the parades issue has provided an outlet for the violence of paramilitary groups who are otherwise on ceasefire.

The Troubles' impact on the ordinary people of Northern Ireland produced such psychological trauma that the city of Belfast had been compared to London during the Blitz. The stress resulting from bomb attacks, street disturbances, security checkpoints, and the constant military presence had the strongest effect on children and young adults. In addition to the violence and intimidation, there was chronic unemployment and a severe housing shortage. Vandalism was also a major problem. In the 1970s there were 10,000 vandalised empty houses in Belfast alone. Most of the vandals were aged between eight and thirteen. Activities for young people were limited, with pubs fortified and cinemas closed. Just to go shopping in the city centre required passing through security gates and being subjected to body searches.

The Troubles' impact on the ordinary people of Northern Ireland produced such psychological trauma that the city of Belfast had been compared to London during the Blitz. The stress resulting from bomb attacks, street disturbances, security checkpoints, and the constant military presence had the strongest effect on children and young adults. In addition to the violence and intimidation, there was chronic unemployment and a severe housing shortage. Vandalism was also a major problem. In the 1970s there were 10,000 vandalised empty houses in Belfast alone. Most of the vandals were aged between eight and thirteen. Activities for young people were limited, with pubs fortified and cinemas closed. Just to go shopping in the city centre required passing through security gates and being subjected to body searches.

Social intercourse was also affected. Normal interaction and friendship with people from the opposite side of the religious/political divide was nearly impossible in the atmosphere of fear and distrust that the Troubles generated.

According to one historian of the conflict, the stress of the Troubles engendered a breakdown in the previously strict sexual morality of Northern Ireland, resulting in a "confused hedonism" in respect of personal life. In Derry, illegitimate births and alcoholism increased for women and the divorce rate rose. Teenage alcoholism was also a problem, partly as a result of the drinking clubs established in both loyalist and republican areas. In many cases, there was little parental supervision of children in some of the poorer districts.

The Department of Health has looked at a report written in 2007 by Mike Tomlinson of Queen's University

, which asserted that the legacy of the Troubles has played a substantial role in the current high rate of suicide in Northern Ireland.

Approximately 60% of the dead were killed by republicans, 30% by loyalists and 10% by British security forces.

and three Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) members killed during the conflict were also Ulster Defence Regiment

(UDR) soldiers at the time of their deaths.

At least one civilian victim was an off-duty member of the TA.

, were also affected, albeit to a lesser degree than Northern Ireland itself. Occasionally, violence also took place in western Europe, especially against the British Army

and to a lesser extent against the Royal Air Force

in Germany.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

which spilled over at various times into England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

, and mainland Europe

Continental Europe

Continental Europe, also referred to as mainland Europe or simply the Continent, is the continent of Europe, explicitly excluding European islands....

. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement of 1998. , sporadic violence has nonetheless continued.

The principal issues at stake in the Troubles were the constitutional status of Northern Ireland

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland was the division of the island of Ireland into two distinct territories, now Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . Partition occurred when the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920...

and the relationship between the mainly Protestant unionist

Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is an ideology that favours the continuation of some form of political union between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain...

and mainly Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

nationalist

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

communities in Northern Ireland. The Troubles had both political and military (or paramilitary) dimensions. Its participants included republican

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

and loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

paramilitaries

Paramilitary

A paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

, the security forces of the United Kingdom and of the Republic of Ireland, and nationalist and unionist politicians and political activists.

Overview

"The Troubles" refers to approximately three decades of violence between elements of Northern Ireland's nationalist community (who mainly self-identified as IrishIrish people

The Irish people are an ethnic group who originate in Ireland, an island in northwestern Europe. Ireland has been populated for around 9,000 years , with the Irish people's earliest ancestors recorded having legends of being descended from groups such as the Nemedians, Fomorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha...

and/or Roman Catholic) and its unionist community (who mainly self-identified as British

British people

The British are citizens of the United Kingdom, of the Isle of Man, any of the Channel Islands, or of any of the British overseas territories, and their descendants...

and/or Protestant). Use of the term "the Troubles" has been raised at Northern Ireland Assembly

Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly is the devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and to appoint the Northern Ireland Executive...

level, as some people considered this period of conflict to have been a war. The conflict was the result of discrimination against the Nationalist/Catholic minority by the Unionist/Protestant majority and the question of Northern Ireland's status within the United Kingdom. The violence was characterised by the armed campaigns of Irish republican

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

and Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

paramilitary groups. This included the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) campaign of 1969–1997

Provisional IRA campaign 1969–1997

From 1969 until 1997, the Provisional Irish Republican Army conducted an armed paramilitary campaign in Northern Ireland and England, aimed at ending British rule in Northern Ireland in order to create a united Ireland....

, intended to end British rule in Northern Ireland and to reunite Ireland

United Ireland

A united Ireland is the term used to refer to the idea of a sovereign state which covers all of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. The island of Ireland includes the territory of two independent sovereign states: the Republic of Ireland, which covers 26 counties of the island, and the...

politically and thus create a new "all-Ireland" Irish Republic

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic was a revolutionary state that declared its independence from Great Britain in January 1919. It established a legislature , a government , a court system and a police force...

; and of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), formed in 1966 in response to the perceived erosion of both the British character and unionist domination of Northern Ireland. The state security forces — the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

(RUC) — were also involved in the violence.

The British Government's view was that its forces were neutral in the conflict, trying to uphold law and order in Northern Ireland and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to democratic self-determination. Irish republicans, however, regarded the state forces as forces of occupation and combatants in the conflict, noting collusion

Collusion

Collusion is an agreement between two or more persons, sometimes illegal and therefore secretive, to limit open competition by deceiving, misleading, or defrauding others of their legal rights, or to obtain an objective forbidden by law typically by defrauding or gaining an unfair advantage...

between the state forces and the loyalist paramilitaries. The "Ballast" investigation by the Police Ombudsman

Police Ombudsman

The Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland is a non-departmental public body intended to provide an independent, impartial police complaints system for the people and police under the Police Acts of 1998 and 2000.-Personnel:...

has confirmed that British forces, and in particular the RUC, did, on several occasions, collude with loyalist paramilitaries, were involved in murder, and did obstruct the course of justice when such claims had previously been investigated. The extent of collusion is still hotly disputed. Unionists claim that reports of collusion were either false or highly exaggerated and that there were also instances of collusion between the authorities of the Republic of Ireland and republican paramilitaries.

Alongside the violence, there was a political deadlock between the major political parties in Northern Ireland, including those who condemned violence, over the future status of Northern Ireland and the form of government there should be within Northern Ireland.

The Troubles were brought to an uneasy end by a peace process

Northern Ireland peace process

The peace process, when discussing the history of Northern Ireland, is often considered to cover the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Belfast Agreement, and subsequent political developments.-Towards a...

. It included the declaration of ceasefires by most paramilitary organisations, the complete decommissioning of the IRA's weapons, the reform of the police, and the corresponding withdrawal of army troops from the streets and sensitive border areas such as South Armagh

South Armagh

South Armagh can refer to:*The southern part of County Armagh*South Armagh *South Armagh...

and Fermanagh, as agreed by the signatories to the Belfast Agreement

Belfast Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement , sometimes called the Stormont Agreement, was a major political development in the Northern Ireland peace process...

(commonly known as the "Good Friday Agreement"). The agreement reiterated the long-held British position, which successive Irish governments had not fully acknowledged, that Northern Ireland would remain within the United Kingdom, until a majority of people in Northern Ireland voted otherwise.

On the other hand, the British Government recognised for the first time the principle that the people of the island of Ireland as a whole have the right, without any outside interference, to solve the issues between North and South by mutual consent. The latter statement was key to winning support for the agreement from nationalists and republicans. It also established a devolved power-sharing government within Northern Ireland (which had been suspended from 14 October 2002 until 8 May 2007), where the government must consist of both unionist and nationalist parties.

Though the number of active participants in the Troubles was relatively small, the Troubles touched the lives of many people in Northern Ireland on a daily basis, while occasionally spreading to the Republic of Ireland and England.

1609–1912

Settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established permanent residence there, often to colonize the area. Settlers are generally people who take up residence on land and cultivate it, as opposed to nomads...

s, known as planters, were given land confiscated from the native Irish in the Plantation of Ulster

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation of Ulster—a province of Ireland—by people from Great Britain. Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while official plantation controlled by King James I of England and VI of Scotland began in 1609...

. Coupled with Protestant immigration to "unplanted" areas of Ulster, particularly Antrim and Down, this resulted in conflict between the native Catholics and the "planters". This led to two bloody ethno-religious conflicts known as the Irish Confederate Wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

(1641–1653) and the Williamite war

Williamite war in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland—also called the Jacobite War in Ireland, the Williamite-Jacobite War in Ireland and in Irish as Cogadh an Dá Rí —was a conflict between Catholic King James II and Protestant King William of Orange over who would be King of England, Scotland and Ireland...

(1689–1691), both of which resulted in Protestant victories.

British Protestant political dominance in Ireland was ensured by the passage of the penal laws

Penal Laws (Ireland)

The term Penal Laws in Ireland were a series of laws imposed under English and later British rule that sought to discriminate against Roman Catholics and Protestant dissenters in favour of members of the established Church of Ireland....

, which curtailed the religious, legal and political rights of anyone (including both Catholics and (Protestant) Dissenters, such as Presbyterians) who did not conform to the state church—the Anglican Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

.

As the penal laws broke down in the latter part of the eighteenth century, there was more competition for land, as restrictions were lifted on the Catholic Irish

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

ability to rent. With Roman Catholics allowed to buy land and enter trades from which they had formerly been banned, Protestant "Peep O'Day Boys

Peep O'Day Boys

The Peep o' Day Boys was a Protestant secret association in 18th century Ireland, active in the 1780s and '90s and a precursor of the Orange Order.-Origins:The Peep-of-day Boys arose in the year 1784, in County Armagh, Ireland...

" attacks on that community increased. In the 1790s Catholics in south Ulster organised as "The Defenders

Defenders (Ireland)

The Defenders were a militant, vigilante agrarian secret society in 18th century Ireland, mainly Roman Catholic and from Ulster, who allied with the United Irishmen but did little during the rebellion of 1798.-Origin:...

" and counter-attacked. This created polarisation between the communities and a dramatic reduction in reformers within the Protestant community which had been growing more receptive to ideas of democratic reform.

Following the foundation of the nationalist-based Society of the United Irishmen

Society of the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was founded as a liberal political organisation in eighteenth century Ireland that sought Parliamentary reform. However, it evolved into a revolutionary republican organisation, inspired by the American Revolution and allied with Revolutionary France...

by Presbyterians, Catholics and liberal Anglicans, and the resulting failed Irish Rebellion of 1798

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

, sectarian violence

between Catholics and Protestants continued. The Orange Order

Orange Institution

The Orange Institution is a Protestant fraternal organisation based mainly in Northern Ireland and Scotland, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth and United States. The Institution was founded in 1796 near the village of Loughgall in County Armagh, Ireland...

(founded in 1795), with its stated goal of upholding the Protestant faith and loyalty to William of Orange

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

and his heirs, dates from this period and remains active to this day.

In 1801, a new political framework was formed with the abolition of the Irish Parliament and incorporation of Ireland into the United Kingdom

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

. The result was a closer tie between the former, largely pro-republican Presbyterians and Anglicans as part of a "loyal" Protestant community. Though Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

was achieved in 1829, in large part by Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell (6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847; often referred to as The Liberator, or The Emancipator, was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century...

, largely eliminating legal discrimination against Catholics (around 75% of Ireland's population), Jews and Dissenters, O'Connell's long-term goals of Repeal of the 1801 Union and Home Rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

were never achieved. The Home Rule movement served to define the divide between most nationalists

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

(often Catholics), who sought the restoration of an Irish Parliament, and most unionists (often Protestants), who were afraid of being a minority in a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament and tended to support continuing union with Britain. Unionists and Home-Rule advocates countered each other during the career of Charles Stuart Parnell, a repealer, and onwards.

1912–1922

By the second decade of the 20th century Home Rule, or limited Irish self-government, was on the brink of being conceded due to the agitation of the Irish Parliamentary PartyIrish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party was formed in 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament elected to the House of Commons at...

. In response, unionists, mostly Protestant and concentrated in Ulster, resisted both self-government and independence for Ireland, fearing for their future in an overwhelmingly Catholic country dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1912, unionists led by Edward Carson signed the Ulster Covenant

Ulster Covenant

The Ulster Covenant was signed by just under half a million of men and women from Ulster, on and before September 28, 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill, introduced by the Government in that same year...

and pledged to resist Home Rule by force if necessary. To this end, they formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers and imported arms from Germany (the Easter Rising

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising was an insurrection staged in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. The Rising was mounted by Irish republicans with the aims of ending British rule in Ireland and establishing the Irish Republic at a time when the British Empire was heavily engaged in the First World War...

insurrectionists did the same several years later).

Nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers

Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland"...

, whose ostensible goal was to oppose the Ulster Volunteers and ensure the enactment of the Third Home Rule Bill

Home Rule Act 1914