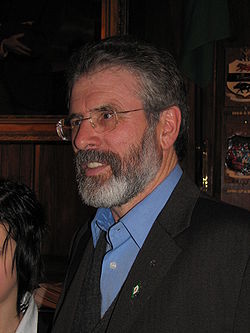

Gerry Adams

Encyclopedia

Gerry Adams is an Irish republican

politician and Teachta Dála (TD

) for the constituency of Louth

. From 1983 to 1992 and from 1997 to 2011, he was an abstentionist

Westminster

Member of Parliament

for Belfast West

. He is the president of Sinn Féin

, the second largest political party in Northern Ireland and the largest nationalist party. From the late 1980s onwards, Adams was an important figure in the Northern Ireland peace process

, initially following contact by the then Social Democratic and Labour Party

(SDLP) leader John Hume

and subsequently with the Irish

and British governments and then other parties. In 2005, the Provisional Irish Republican Army

(IRA) indicated that its armed campaign was over and that it is now exclusively committed to democratic politics. Under Adams, Sinn Féin changed its traditional policy of abstentionism towards Oireachtas Éireann, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland

, in 1986 and later took seats in the power-sharing

Northern Ireland Assembly

. However, Sinn Féin retains a policy of abstentionism towards the Westminster Parliament, but since 2002, receives allowances for staff and takes up offices in the House of Commons.

and Annie Hannaway came from republican backgrounds. Adams' grandfather, also called Gerry Adams, had been a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

(IRB) during the Irish War of Independence

. Two of Adams' uncles, Dominic and Patrick Adams, had been interned by the governments in Belfast and Dublin. Although it is reported that his uncle Dominic was a one-time IRA chief of staff, J. Bowyer Bell

states in his book, The Secret Army: The IRA 1916 (Irish Academy Press), that Dominic Adams was a senior figure in the IRA of the mid-1940s. Gerry Sr. joined the IRA

at age sixteen. In 1942, he participated in an IRA ambush on a Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC) patrol but was himself shot, arrested and sentenced to eight years imprisonment.

Adams' maternal great-grandfather, Michael Hannaway, was a member of the Fenians during their dynamiting campaign in England in the 1860s and 1870s. Michael's son, Billy, was election agent for Éamon de Valera

in 1918 in West Belfast

but refused to follow de Valera into democratic and constitutional politics upon the formation of Fianna Fáil

.

Annie Hannaway was a member of Cumann na mBan

, the women's branch of the IRA. Three of her brothers (Alfie, Liam and Tommy) were known IRA members.

Adams attended St Finian's Primary School

on the Falls Road where he was taught by De La Salle brothers

. Having passed the eleven-plus exam in 1960, he attended St Mary's Christian Brothers Grammar School. He left St. Mary's with six O-levels and became a barman

. He was increasingly involved in the Irish republican movement, joining Sinn Féin and Fianna Éireann

in 1964, after being radicalised by the Divis Street riots during that years general election

campaign.

In 1971, Adams married Collette McArdle, with whom he has three children.

In the late 1960s, a civil rights campaign developed in Northern Ireland. Adams was an active supporter and joined the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

In the late 1960s, a civil rights campaign developed in Northern Ireland. Adams was an active supporter and joined the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

in 1967. However, the civil rights movement was met with protests from loyalist

counter-demonstrators. In August 1969, Northern Ireland cities like Belfast and Derry

erupted in major rioting and British troops were called in at the request of the Government of Northern Ireland (see 1969 Northern Ireland Riots

).

Adams was active in Sinn Féin at this time, siding with the Provisionals in the split of 1970. In August 1971, internment

was reintroduced to Northern Ireland under the Special Powers Act 1922

. Adams was interned in March 1972, on , but was released in June to take part in secret, but abortive talks in London. The IRA negotiated a short-lived truce with the British government and an IRA delegation met with the British Home Secretary, William Whitelaw at Cheyne Walk

in Chelsea. The delegation included Gerry Adams, Martin McGuinness

, Sean Mac Stiofain

(IRA Chief of Staff), Daithi O'Conaill, Seamus Twomey

, Ivor Bell

and Dublin solicitor Myles Shevlin

. The IRA insisted Adams be included in the meeting and he was released from internment to participate. Following the failure of the talks, he played a central role in planning the bomb blitz on Belfast known as Bloody Friday

. He was re-arrested in July 1973 and interned at the Long Kesh

internment camp. After taking part in an IRA-organised escape attempt, he was sentenced to a period of imprisonment. During this time, he wrote articles in the paper An Phoblacht

under the by-line "Brownie", where he criticized the strategy and policy of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

and Billy McKee

. He was also highly critical of a decision taken in Belfast by McKee to assassinate members of the rival Official IRA

, who had been on ceasefire since 1972. After his release in 1976, he was again arrested in 1978 for alleged IRA membership, the charges were subsequently dismissed.

During the 1981 hunger strike

, Adams played an important policy-making role, which saw the emergence of his party as a political force. In 1983, he was elected president of Sinn Féin and became the first Sinn Féin MP elected to the British House of Commons since Phil Clarke

and Tom Mitchell in the mid-1950s. Following his election as MP for Belfast West

, the British

government lifted a ban on him travelling to Great Britain

. In line with Sinn Féin policy, he refused to take his seat in the House of Commons.

On 14 March 1984 in central Belfast, Adams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt when several Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) gunmen fired about 20 shots into the car in which he was travelling. He was hit in the neck, shoulder and arm. After the shooting, he was rushed to the Royal Victoria Hospital

, where he underwent surgery to remove the three bullets which had entered his body. Under-cover plain clothes police officers seized three suspects who were later convicted and sentenced. One of the three was John Gregg

, who would be killed by Loyalists in 2003. Adams claimed that the British army

had prior knowledge of the attack and allowed it to go ahead.

(IRA). However, authors such as Ed Moloney

, Peter Taylor

, Mark Urban

and historian Richard English

have all named Adams as part of the IRA leadership since the 1970s. Adams has denied Moloney's claims, calling them "libellous".

and joint vice- president Dáithí Ó Conaill

.

The 1975 IRA-British truce is often viewed as the event that began the challenge to the original Provisional Sinn Féin leadership, which was said to be Southern-based and dominated by southerners like Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill. However, the Chief of Staff of the IRA at the time, Seamus Twomey

, was a senior figure from Belfast. Others in the leadership were also Northern based, including Billy McKee

from Belfast. Adams (allegedly) rose to become the most senior figure in the IRA Northern Command

on the basis of his absolute rejection of anything but military action, but this conflicts with the fact that during his time in prison, Adams came to reassess his approach and became more political.

One of the reasons that the Provisional IRA and provisional Sinn Féin were founded, in December 1969 and January 1970, respectively, was that people like Ó Brádaigh, O'Connell and McKee opposed participation in constitutional politics. The other reason was the failure of the Goulding leadership to provide for the defence of nationalist areas. When, at the December 1969 IRA convention and the January 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis the delegates voted to participate in the Dublin (Leinster House), Belfast (Stormont) and London (Westminster) parliaments, the organizations split. Gerry Adams, who had joined the Republican Movement in the early 1960s, sided with the Provisionals.

In The Empire of Great Kesh in the mid-1970s, and writing under the pseudonym "Brownie" in Republican News

, Adams called on Republicans for increased political activity, especially at a local level. The call resonated with younger Northern people, many of whom had been active in the Provisional IRA but had not necessarily been highly active in Sinn Féin. In 1977, Adams and Danny Morrison drafted the address of Jimmy Drumm at the Annual Wolfe Tone Commemoration at Bodenstown. The address was viewed as watershed in that Drumm acknowledged that the war would be a long one and that success depended on political activity that would complement the IRA's armed campaign. For some, this wedding of politics and armed struggle culminated in Danny Morrison's statement at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in which he asked "Who here really believes we can win the war through the Ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in one hand and the Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland". For others, however, the call to link political activity with armed struggle had been clearly defined in Sinn Féin policy and in the Presidential Addresses of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

, but it had not resonated with the young Northerners.

Even after the election of Bobby Sands

Even after the election of Bobby Sands

as MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone, a part of the mass mobilization associated with the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike

by republican prisoners in the H blocks of the Maze prison (known as Long Kesh by Republicans), Adams was cautious about the level of political involvement by Sinn Féin. Charles Haughey

, the Taoiseach

of the Republic of Ireland, called an election

for June 1981. At an Ard Chomhairle meeting, Adams recommended that they contest only four constituencies which were in border counties. Instead, H-Block/Armagh Candidates contested nine constituencies and elected two TDs. This, along with the election of Bobby Sands, was a precursor to a big electoral breakthrough in elections in 1982 to the Northern Ireland Assembly. Adams, Danny Morrison, Martin McGuinness

, Jim McAllister

, and Owen Carron

were elected as abstentionists. The Social Democratic Labour Party

(SDLP) had announced before the election that it would not take any seats and so its 14 elected representatives also abstained from participating in the Assembly and it was a failure. The 1982 election was followed by the 1983 Westminster election

, in which Sinn Féin's vote increased and Gerry Adams was elected, as an abstentionist, as MP for Belfast West. It was in 1983 that Ruairí Ó Brádaigh resigned as President of Sinn Féin and was succeeded by Gerry Adams.

Republicans had long claimed that the only legitimate Irish state was the Irish Republic

declared in the Proclamation of the Republic of 1916, which they considered to be still in existence. In their view, the legitimate government was the IRA Army Council

, which had been vested with the authority of that Republic in 1938 (prior to the Second World War

) by the last remaining anti-Treaty

deputies of the Second Dáil

. Adams continued to adhere to this claim of republican political legitimacy until quite recently — however, in his 2005 speech to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis

he explicitly rejected it. "But we refuse to criminalise those who break the law in pursuit of legitimate political objectives. ... Sinn Féin is accused of recognising the Army Council of the IRA as the legitimate government of this island. That is not the case. ... do not believe that the Army Council is the government of Ireland. Such a government will only exist when all the people of this island elect it. Does Sinn Féin accept the institutions of this state as the legitimate institutions of this state? Of course we do."

As a result of this non-recognition, Sinn Féin had abstained from taking any of the seats they won in the British or Irish parliaments. At its 1986 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin delegates passed a resolution to amend the rules and constitution that would allow its members to sit in the Dublin parliament (Leinster House/Dáil Éireann). At this, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

led a small walkout, just as he and Sean Mac Stiofain had done sixteen years earlier with the creation of Provisional Sinn Féin. This minority, which rejected dropping the policy of abstentionism

, now nominally distinguishes itself from Provisional Sinn Féin by using the name Republican Sinn Féin

(or Sinn Féin Poblachtach), and maintains that they are the true Sinn Féin republicans.

Adams' leadership of Sinn Féin was supported by a Northern-based cadre that included people like Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness

. Over time, Adams and others pointed to Republican electoral successes in the early and mid-1980s, when hunger strikers Bobby Sands

and Kieran Doherty

were elected to the British House of Commons and Dáil Éireann

respectively, and they advocated that Sinn Féin become increasingly political and base its influence on electoral politics rather than paramilitarism. The electoral effects of this strategy were shown later by the election of Adams and McGuinness to the House of Commons.

and loyalist organisations, but in practice Adams was the only one prominent enough to appear regularly on TV). This ban was imposed by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher

on 19 October 1988, the reason given being to "starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend" after the BBC interviewed Martin McGuinness

and Adams had been the focus of a row over an edition of After Dark, an intended Channel 4

discussion programme which was never made.

A similar ban, known as Section 31, had been law in the Republic of Ireland since the 1970s. However, media outlets soon found ways around the ban, initially by the use of subtitles, but later and more commonly by the use of an actor reading his words over the images of him speaking. One actor who voiced Adams was Paul Loughran

.

This ban was lampooned in cartoons and satirical TV shows, such as Spitting Image

, and in The Day Today

and was criticised by freedom of speech

organisations and British media personalities, including BBC Director General John Birt and BBC foreign editor John Simpson. The ban was lifted by British Prime Minister John Major

on 17 September 1994.

even after Adams won the Belfast West

constituency. He lost his seat to Joe Hendron

of the Social Democratic and Labour Party

(SDLP) in the 1992 general election

, regaining it at the next election five years later

.

Under Adams, Sinn Féin appeared to move away from being a political voice of the Provisional IRA to becoming a professionally organised political party in both Northern Ireland

and the Republic of Ireland

.

SDLP leader John Hume

, MP, identified the possibility that a negotiated settlement might be possible and began secret talks with Adams in 1988. These discussions led to unofficial contacts with the British Northern Ireland Office

under the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

, Peter Brooke

, and with the government of the Republic under Charles Haughey

– although both governments maintained in public that they would not negotiate with "terrorists".

These talks provided the groundwork for what was later to be the Belfast Agreement

, as well as the milestone Downing Street Declaration

and the Joint Framework Document.

These negotiations led to the IRA ceasefire in August 1994. Irish Taoiseach

Albert Reynolds

, who had replaced Haughey and who had played a key role in the Hume/Adams dialogue through his Special Advisor Martin Mansergh

, regarded the ceasefire as permanent. However, the slow pace of developments contributed in part to the (wider) political difficulties of the British government of John Major

and the consequent reliance on Ulster Unionist Party

votes in the House of Commons, led the IRA to end its ceasefire and resume the campaign.

A re-instituted ceasefire later followed as part of the negotiations strategy, which saw teams from the British and Irish governments, the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP, Sinn Féin and representatives of loyalist paramilitary organizations, under the chairmanship of former United States Senator George Mitchell

, produced the Belfast Agreement (also called the Good Friday Agreement as it was signed on Good Friday

, 1998). Under the agreement, structures were created reflecting the Irish and British identities of the people of Ireland, with a British-Irish Council

and a Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly

created.

Articles 2 and 3 of the Republic's constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, which claimed sovereignty over all of Ireland, were reworded, and a power-sharing Executive Committee was provided for. As part of their deal, Sinn Féin agreed to abandon its abstentionist policy regarding a "six-county parliament", as a result taking seats in the new Stormont

-based Assembly and running the education and health and social services ministries in the power-sharing government.

On 15 August 1998, four months after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the Real IRA exploded a car bomb

in Omagh

, County Tyrone

, killing 31 people and injuring 220, from many communities. Breaking with tradition, Adams said in reaction to the bombing "I am totally horrified by this action. I condemn it without any equivocation whatsoever." Prior to this, Adams had maintained a policy of refusing to condemn IRA or their splinter groups' actions.

Opponents in Republican Sinn Féin accused Sinn Féin of "selling out" by agreeing to participate in what it called "partitionist

assemblies" in the Republic and Northern Ireland. However, Gerry Adams insisted that the Belfast Agreement provided a mechanism to deliver a united Ireland by non-violent and constitutional means, much as Michael Collins

had said of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

nearly 80 years earlier.

When Sinn Féin came to nominate its two ministers to the Northern Ireland Executive, for tactical reasons the party, like the SDLP and the Democratic Unionist Party

(DUP), chose not to include its leader among its ministers. (When later the SDLP chose a new leader, it selected one of its ministers, Mark Durkan

, who then opted to remain in the Committee.)

Adams remains the President of Sinn Féin. In 2011 he succeeded Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin

as Sinn Féin parliamentary leader in Dáil Éireann. Daithí McKay

is the head of the Sinn Féin group in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Adams was re-elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 8 March 2007, and on 26 March 2007, he met with DUP leader Ian Paisley

face-to-face for the first time, and the two came to an agreement regarding the return of the power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland.

In January 2009, Adams attended the United States presidential Inauguration of Barack Obama

as a guest of US Congressman Richard Neal

.

On 6 May 2010, Adams was re-elected as MP for West Belfast garnering 71.1% of the vote. In 2011 the Chancellor appointed Adams to the British title of Steward and Bailiff of the Manor of Northstead to allow him to resign from the House of Commons and to stand for election in the Dáil. Initially it was claimed by David Cameron that Adams had accepted the title but Downing Street has since apologized for this and Adams has publicly rejected the title stating, "I have had no truck whatsoever with these antiquated and quite bizarre aspects of the British parliamentary system".

(member of Irish Parliament) for the constituency of Louth

at the 2011 Irish general election. He subsequently resigned his West Belfast Assembly

seat on 7 December 2010.

Following the announcement of the Irish general election, 2011, Adams wrote to the House of Commons to resign his seat. This was treated as an application for the position of Crown Steward and Bailiff of the Manor of Northstead, an office of profit

under the Crown, the traditional method of leaving Westminster as plain resignation is not possible, and granted as such even though Adams had not explicitly made the request.

He was elected to the Dáil, topping the Louth constituency poll with 15,072 (21.7%) first preference votes.

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

politician and Teachta Dála (TD

Teachta Dála

A Teachta Dála , usually abbreviated as TD in English, is a member of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas . It is the equivalent of terms such as "Member of Parliament" or "deputy" used in other states. The official translation of the term is "Deputy to the Dáil", though a more literal...

) for the constituency of Louth

Louth (Dáil Éireann constituency)

Louth is a parliamentary constituency represented in Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Irish parliament or Oireachtas. The constituency elects 5 deputies...

. From 1983 to 1992 and from 1997 to 2011, he was an abstentionist

Abstentionism

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in the election itself...

Westminster

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

for Belfast West

Belfast West (UK Parliament constituency)

Belfast West is a parliamentary constituency in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.-Boundaries:The seat was restored in 1922 when as part of the establishment of the devolved Stormont Parliament for Northern Ireland, the number of MPs in the Westminster Parliament was drastically cut...

. He is the president of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

, the second largest political party in Northern Ireland and the largest nationalist party. From the late 1980s onwards, Adams was an important figure in the Northern Ireland peace process

Northern Ireland peace process

The peace process, when discussing the history of Northern Ireland, is often considered to cover the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Belfast Agreement, and subsequent political developments.-Towards a...

, initially following contact by the then Social Democratic and Labour Party

Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party is a social-democratic, Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. Its basic party platform advocates Irish reunification, and the further devolution of powers while Northern Ireland remains part of the United Kingdom...

(SDLP) leader John Hume

John Hume

John Hume is a former Irish politician from Derry, Northern Ireland. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize, with David Trimble....

and subsequently with the Irish

Irish Government

The Government of Ireland is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.-Members of the Government:Membership of the Government is regulated fundamentally by the Constitution of Ireland. The Government is headed by a prime minister called the Taoiseach...

and British governments and then other parties. In 2005, the Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

(IRA) indicated that its armed campaign was over and that it is now exclusively committed to democratic politics. Under Adams, Sinn Féin changed its traditional policy of abstentionism towards Oireachtas Éireann, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

, in 1986 and later took seats in the power-sharing

D'Hondt method

The d'Hondt method is a highest averages method for allocating seats in party-list proportional representation. The method described is named after Belgian mathematician Victor D'Hondt who described it in 1878...

Northern Ireland Assembly

Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly is the devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and to appoint the Northern Ireland Executive...

. However, Sinn Féin retains a policy of abstentionism towards the Westminster Parliament, but since 2002, receives allowances for staff and takes up offices in the House of Commons.

Ancestry and early life

Adams' parents, Gerry Adams Sr.Gerry Adams Sr.

Gerry Adams Sr. was a Belfast Irish Republican Army volunteer who took part in its Northern Campaign in the 1940s....

and Annie Hannaway came from republican backgrounds. Adams' grandfather, also called Gerry Adams, had been a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

(IRB) during the Irish War of Independence

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence , Anglo-Irish War, Black and Tan War, or Tan War was a guerrilla war mounted by the Irish Republican Army against the British government and its forces in Ireland. It began in January 1919, following the Irish Republic's declaration of independence. Both sides agreed...

. Two of Adams' uncles, Dominic and Patrick Adams, had been interned by the governments in Belfast and Dublin. Although it is reported that his uncle Dominic was a one-time IRA chief of staff, J. Bowyer Bell

J. Bowyer Bell

J. Bowyer Bell was an American historian, artist and art critic.-Background and early life:Bell was born into an Episcopalian family on 15 November 1931 in New York City. The family later moved to Alabama, from where Bell attended Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, majoring in...

states in his book, The Secret Army: The IRA 1916 (Irish Academy Press), that Dominic Adams was a senior figure in the IRA of the mid-1940s. Gerry Sr. joined the IRA

Irish Republican Army (1922–1969)

The original Irish Republican Army fought a guerrilla war against British rule in Ireland in the Irish War of Independence 1919–1921. Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921, the IRA in the 26 counties that were to become the Irish Free State split between supporters and...

at age sixteen. In 1942, he participated in an IRA ambush on a Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

(RUC) patrol but was himself shot, arrested and sentenced to eight years imprisonment.

Adams' maternal great-grandfather, Michael Hannaway, was a member of the Fenians during their dynamiting campaign in England in the 1860s and 1870s. Michael's son, Billy, was election agent for Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

in 1918 in West Belfast

Belfast West (UK Parliament constituency)

Belfast West is a parliamentary constituency in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.-Boundaries:The seat was restored in 1922 when as part of the establishment of the devolved Stormont Parliament for Northern Ireland, the number of MPs in the Westminster Parliament was drastically cut...

but refused to follow de Valera into democratic and constitutional politics upon the formation of Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party , more commonly known as Fianna Fáil is a centrist political party in the Republic of Ireland, founded on 23 March 1926. Fianna Fáil's name is traditionally translated into English as Soldiers of Destiny, although a more accurate rendition would be Warriors of Fál...

.

Annie Hannaway was a member of Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914 as an auxiliary of the Irish Volunteers...

, the women's branch of the IRA. Three of her brothers (Alfie, Liam and Tommy) were known IRA members.

Adams attended St Finian's Primary School

St Finian's Primary School

St. Finian's Primary School was a Roman Catholic primary school located in the Falls Road area of West Belfast. It was run by the De La Salle Christian Brothers. In view of its high educational standards it attracted pupils not only from the Falls Road but other Catholic districts in Belfast. Due...

on the Falls Road where he was taught by De La Salle brothers

Roman Catholic religious order

Catholic religious orders are, historically, a category of Catholic religious institutes.Subcategories are canons regular ; monastics ; mendicants Catholic religious orders are, historically, a category of Catholic religious institutes.Subcategories are canons regular (canons and canonesses regular...

. Having passed the eleven-plus exam in 1960, he attended St Mary's Christian Brothers Grammar School. He left St. Mary's with six O-levels and became a barman

Public house

A public house, informally known as a pub, is a drinking establishment fundamental to the culture of Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. There are approximately 53,500 public houses in the United Kingdom. This number has been declining every year, so that nearly half of the smaller...

. He was increasingly involved in the Irish republican movement, joining Sinn Féin and Fianna Éireann

Fianna Éireann

The name Fianna Éireann , also written Fianna na hÉireann and Na Fianna Éireann , has been used by various Irish republican youth movements throughout the 20th and 21st centuries...

in 1964, after being radicalised by the Divis Street riots during that years general election

United Kingdom general election, 1964

The United Kingdom general election of 1964 was held on 15 October 1964, more than five years after the preceding election, and thirteen years after the Conservative Party had retaken power...

campaign.

In 1971, Adams married Collette McArdle, with whom he has three children.

Early political career

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was an organisation which campaigned for equal civil rights for the all the people in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s...

in 1967. However, the civil rights movement was met with protests from loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

counter-demonstrators. In August 1969, Northern Ireland cities like Belfast and Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

erupted in major rioting and British troops were called in at the request of the Government of Northern Ireland (see 1969 Northern Ireland Riots

1969 Northern Ireland Riots

During 12–17 August 1969, Northern Ireland was rocked by intense political and sectarian rioting. There had been sporadic violence throughout the year arising from the civil rights campaign, which was demanding an end to government discrimination against Irish Catholics and nationalists...

).

Adams was active in Sinn Féin at this time, siding with the Provisionals in the split of 1970. In August 1971, internment

Internment

Internment is the imprisonment or confinement of people, commonly in large groups, without trial. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the meaning as: "The action of 'interning'; confinement within the limits of a country or place." Most modern usage is about individuals, and there is a distinction...

was reintroduced to Northern Ireland under the Special Powers Act 1922

Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) 1922

The Civil Authorities Act 1922, often referred to simply as the Special Powers Act, was an Act passed by the Parliament of Northern Ireland shortly after the establishment of Northern Ireland, and in the context of violent conflict over the issue of the partition of Ireland...

. Adams was interned in March 1972, on , but was released in June to take part in secret, but abortive talks in London. The IRA negotiated a short-lived truce with the British government and an IRA delegation met with the British Home Secretary, William Whitelaw at Cheyne Walk

Cheyne Walk

Cheyne Walk , is a historic street in Chelsea, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It takes its name from William Lord Cheyne who owned the manor of Chelsea until 1712. Most of the houses were built in the early 18th century. Before the construction in the 19th century of the busy...

in Chelsea. The delegation included Gerry Adams, Martin McGuinness

Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness is an Irish Sinn Féin politician and the current deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. McGuinness was also the Sinn Féin candidate for the Irish presidential election, 2011. He was born in Derry, Northern Ireland....

, Sean Mac Stiofain

Seán Mac Stíofáin

Seán Mac Stíofáin was an Irish republican paramilitary activist born in London, who became associated with the republican movement in Ireland after serving in the Royal Air Force...

(IRA Chief of Staff), Daithi O'Conaill, Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey was an Irish republican and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.-Biography:Born in Belfast, Twomey lived at 6 Sevastopol Street in the Falls district...

, Ivor Bell

Ivor Bell

Ivor Malachy Bell is an Irish republican, and a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army who later became Chief of Staff on the Army Council.-IRA career:...

and Dublin solicitor Myles Shevlin

Myles Shevlin

Myles P. Shevlin was an Irish republican Dublin-based solicitor known as 'the Provisionals' "legal adviser"' Shevlin represented several individuals accused of IRA membership and/or activity....

. The IRA insisted Adams be included in the meeting and he was released from internment to participate. Following the failure of the talks, he played a central role in planning the bomb blitz on Belfast known as Bloody Friday

Bloody Friday (1972)

Bloody Friday is the name given to the bombings by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in Belfast on 21 July 1972. Twenty-two bombs exploded in the space of eighty minutes, killing nine people and injuring 130....

. He was re-arrested in July 1973 and interned at the Long Kesh

Maze (HM Prison)

Her Majesty's Prison Maze was a prison in Northern Ireland that was used to house paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from mid-1971 to mid-2000....

internment camp. After taking part in an IRA-organised escape attempt, he was sentenced to a period of imprisonment. During this time, he wrote articles in the paper An Phoblacht

An Phoblacht

An Phoblacht is the official newspaper of Sinn Féin in Ireland. It is published once a month, and according to its website sells an average of up to 15,000 copies every month and was the first Irish paper to provide an edition online and currently having in excess of 100,000 website hits per...

under the by-line "Brownie", where he criticized the strategy and policy of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh is an Irish republican. He is a former chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army , former president of Sinn Féin and former president of Republican Sinn Féin.-Early life:...

and Billy McKee

Billy McKee

Billy McKee is an Irish republican and was a founding member and former leader of the Provisional Irish Republican Army .-Early life:McKee was born in Belfast in the early 1920s, and joined the Irish Republican Army in 1939. During the Second World War, the IRA carried out a number of armed...

. He was also highly critical of a decision taken in Belfast by McKee to assassinate members of the rival Official IRA

Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA is an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to create a "32-county workers' republic" in Ireland. It emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army in December 1969, shortly after the beginning of "The Troubles"...

, who had been on ceasefire since 1972. After his release in 1976, he was again arrested in 1978 for alleged IRA membership, the charges were subsequently dismissed.

During the 1981 hunger strike

1981 Irish hunger strike

The 1981 Irish hunger strike was the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. The protest began as the blanket protest in 1976, when the British government withdrew Special Category Status for convicted paramilitary prisoners...

, Adams played an important policy-making role, which saw the emergence of his party as a political force. In 1983, he was elected president of Sinn Féin and became the first Sinn Féin MP elected to the British House of Commons since Phil Clarke

Philip Clarke

Philip Christopher Clarke was an Irish republican paramilitary and politician.-Early life:Clarke was born in Dublin. A civil servant and an evening student at University College Dublin, Clarke joined the Irish Republican Army and was captured after the IRA raided a British Army barracks in Omagh,...

and Tom Mitchell in the mid-1950s. Following his election as MP for Belfast West

Belfast West (UK Parliament constituency)

Belfast West is a parliamentary constituency in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.-Boundaries:The seat was restored in 1922 when as part of the establishment of the devolved Stormont Parliament for Northern Ireland, the number of MPs in the Westminster Parliament was drastically cut...

, the British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

government lifted a ban on him travelling to Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

. In line with Sinn Féin policy, he refused to take his seat in the House of Commons.

On 14 March 1984 in central Belfast, Adams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt when several Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) gunmen fired about 20 shots into the car in which he was travelling. He was hit in the neck, shoulder and arm. After the shooting, he was rushed to the Royal Victoria Hospital

Royal Victoria Hospital

The Royal Victoria Hospital, or as it is popularly known, the "Royal Vic", is located at 687 Pine Avenue, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.The Royal Vic is located in downtown Montreal, on the slopes of Mount Royal. There are a number of buildings, including the Surgical, Medical, Ross and Women's...

, where he underwent surgery to remove the three bullets which had entered his body. Under-cover plain clothes police officers seized three suspects who were later convicted and sentenced. One of the three was John Gregg

John Gregg (UDA)

John Gregg was a senior member of the UDA/UFF loyalist organisation in Northern Ireland. From the 1990s until his shooting death by rival associates, he served as brigadier of its South East Antrim Brigade...

, who would be killed by Loyalists in 2003. Adams claimed that the British army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

had prior knowledge of the attack and allowed it to go ahead.

Allegations of IRA membership

Adams has stated repeatedly that he has never been a member of the Provisional Irish Republican ArmyProvisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

(IRA). However, authors such as Ed Moloney

Ed Moloney

Ed Moloney is an Irish journalist and author best known for his coverage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and particularly the activities of the Provisional IRA. Ed worked for the Hibernia magazine and Magill before going on to serve as Northern Ireland editor for The Irish Times and...

, Peter Taylor

Peter Taylor (Journalist)

Peter Taylor born in Scarborough, North Riding of Yorkshire is a British journalist and documentary-maker who had covered for many years the political and armed conflict in Northern Ireland, widely known as the Troubles...

, Mark Urban

Mark Urban

Mark Urban is a British journalist, author, broadcaster and orientalist, and is currently the Diplomatic Editor for BBC Two's Newsnight.-Education and early career:...

and historian Richard English

Richard English

Richard English is a historian from Northern Ireland. He was born in Belfast in 1963. His father, Donald English was a prominent Methodist preacher. He studied as an undergraduate at Keble College, Oxford, and subsequently at Keele University, where he was awarded a PhD in History...

have all named Adams as part of the IRA leadership since the 1970s. Adams has denied Moloney's claims, calling them "libellous".

President of Sinn Féin

In 1978, Gerry Adams became joint vice-president of Sinn Féin and a key figure in directing a challenge to the Sinn Féin leadership of President Ruairí Ó BrádaighRuairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh is an Irish republican. He is a former chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army , former president of Sinn Féin and former president of Republican Sinn Féin.-Early life:...

and joint vice- president Dáithí Ó Conaill

Dáithí Ó Conaill

Dáithí Ó Conaill was an Irish republican, a member of the IRA Army Council, vice-president of Sinn Féin and Republican Sinn Féin. He was also the first chief of staff of the Continuity IRA.-Joins IRA:...

.

The 1975 IRA-British truce is often viewed as the event that began the challenge to the original Provisional Sinn Féin leadership, which was said to be Southern-based and dominated by southerners like Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill. However, the Chief of Staff of the IRA at the time, Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey was an Irish republican and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.-Biography:Born in Belfast, Twomey lived at 6 Sevastopol Street in the Falls district...

, was a senior figure from Belfast. Others in the leadership were also Northern based, including Billy McKee

Billy McKee

Billy McKee is an Irish republican and was a founding member and former leader of the Provisional Irish Republican Army .-Early life:McKee was born in Belfast in the early 1920s, and joined the Irish Republican Army in 1939. During the Second World War, the IRA carried out a number of armed...

from Belfast. Adams (allegedly) rose to become the most senior figure in the IRA Northern Command

IRA Northern Command

Northern Command was a command division in the Irish Republican Army and Provisional IRA, responsible for directing IRA operations in the northern part of Ireland.-IRA:...

on the basis of his absolute rejection of anything but military action, but this conflicts with the fact that during his time in prison, Adams came to reassess his approach and became more political.

One of the reasons that the Provisional IRA and provisional Sinn Féin were founded, in December 1969 and January 1970, respectively, was that people like Ó Brádaigh, O'Connell and McKee opposed participation in constitutional politics. The other reason was the failure of the Goulding leadership to provide for the defence of nationalist areas. When, at the December 1969 IRA convention and the January 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis the delegates voted to participate in the Dublin (Leinster House), Belfast (Stormont) and London (Westminster) parliaments, the organizations split. Gerry Adams, who had joined the Republican Movement in the early 1960s, sided with the Provisionals.

In The Empire of Great Kesh in the mid-1970s, and writing under the pseudonym "Brownie" in Republican News

Republican News

Republican News was a longstanding newspaper/magazine published by Sinn Féin. Following the split in physical force Irish republicanism in the late 1960s between the Officials and the Provisionals Republican News was a longstanding newspaper/magazine published by Sinn Féin. Following the split in...

, Adams called on Republicans for increased political activity, especially at a local level. The call resonated with younger Northern people, many of whom had been active in the Provisional IRA but had not necessarily been highly active in Sinn Féin. In 1977, Adams and Danny Morrison drafted the address of Jimmy Drumm at the Annual Wolfe Tone Commemoration at Bodenstown. The address was viewed as watershed in that Drumm acknowledged that the war would be a long one and that success depended on political activity that would complement the IRA's armed campaign. For some, this wedding of politics and armed struggle culminated in Danny Morrison's statement at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in which he asked "Who here really believes we can win the war through the Ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in one hand and the Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland". For others, however, the call to link political activity with armed struggle had been clearly defined in Sinn Féin policy and in the Presidential Addresses of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh is an Irish republican. He is a former chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army , former president of Sinn Féin and former president of Republican Sinn Féin.-Early life:...

, but it had not resonated with the young Northerners.

Bobby Sands

Robert Gerard "Bobby" Sands was an Irish volunteer of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and member of the United Kingdom Parliament who died on hunger strike while imprisoned in HM Prison Maze....

as MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone, a part of the mass mobilization associated with the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike

1981 Irish hunger strike

The 1981 Irish hunger strike was the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. The protest began as the blanket protest in 1976, when the British government withdrew Special Category Status for convicted paramilitary prisoners...

by republican prisoners in the H blocks of the Maze prison (known as Long Kesh by Republicans), Adams was cautious about the level of political involvement by Sinn Féin. Charles Haughey

Charles Haughey

Charles James "Charlie" Haughey was Taoiseach of Ireland, serving three terms in office . He was also the fourth leader of Fianna Fáil...

, the Taoiseach

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government or prime minister of Ireland. The Taoiseach is appointed by the President upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas , and must, in order to remain in office, retain the support of a majority in the Dáil.The current Taoiseach is...

of the Republic of Ireland, called an election

Irish general election, 1981

The Irish general election of 1981 was held on 11 June 1981, three weeks after the dissolution of the Dáil on 21 May. The newly elected 166 members of the 22nd Dáil assembled at Leinster House on 30 June when a new Taoiseach and government were appointed....

for June 1981. At an Ard Chomhairle meeting, Adams recommended that they contest only four constituencies which were in border counties. Instead, H-Block/Armagh Candidates contested nine constituencies and elected two TDs. This, along with the election of Bobby Sands, was a precursor to a big electoral breakthrough in elections in 1982 to the Northern Ireland Assembly. Adams, Danny Morrison, Martin McGuinness

Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness is an Irish Sinn Féin politician and the current deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. McGuinness was also the Sinn Féin candidate for the Irish presidential election, 2011. He was born in Derry, Northern Ireland....

, Jim McAllister

Jim McAllister (Irish republican)

James McAllister , known as Jim McAllister, is an Irish republican activist and former politician.Born in Crossmaglen, County Armagh, McAllister first became involved in the republican movement in the 1950s, at the end of the Border Campaign. He joined Sinn Féin in 1962, but moved to England later...

, and Owen Carron

Owen Carron

Owen Gerard Carron is an Irish republican activist and who was Member of Parliament for Fermanagh and South Tyrone from 1981 to 1983.Carron is the nephew of former Nationalist Party politician John Carron....

were elected as abstentionists. The Social Democratic Labour Party

Social Democratic Labour Party

Social Democratic Labour Party may refer to one of the following.*Estonian Social Democratic Labour Party, successor merged into the Estonian United Left Party*Social Democratic Workers' Party...

(SDLP) had announced before the election that it would not take any seats and so its 14 elected representatives also abstained from participating in the Assembly and it was a failure. The 1982 election was followed by the 1983 Westminster election

United Kingdom general election, 1983

The 1983 United Kingdom general election was held on 9 June 1983. It gave the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher the most decisive election victory since that of Labour in 1945...

, in which Sinn Féin's vote increased and Gerry Adams was elected, as an abstentionist, as MP for Belfast West. It was in 1983 that Ruairí Ó Brádaigh resigned as President of Sinn Féin and was succeeded by Gerry Adams.

Republicans had long claimed that the only legitimate Irish state was the Irish Republic

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic was a revolutionary state that declared its independence from Great Britain in January 1919. It established a legislature , a government , a court system and a police force...

declared in the Proclamation of the Republic of 1916, which they considered to be still in existence. In their view, the legitimate government was the IRA Army Council

IRA Army Council

The IRA Army Council was the decision-making body of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, more commonly known as the IRA, a paramilitary group dedicated to bringing about the end of the Union between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. The council had seven members, said by the...

, which had been vested with the authority of that Republic in 1938 (prior to the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

) by the last remaining anti-Treaty

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of...

deputies of the Second Dáil

Second Dáil

The Second Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. From 1919–1922 Dáil Éireann was the revolutionary parliament of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic. The Second Dáil consisted of members elected in 1921...

. Adams continued to adhere to this claim of republican political legitimacy until quite recently — however, in his 2005 speech to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis

Ard Fheis

Ardfheis or Ard Fheis is the name used by many Irish political parties for their annual party conference. The term was first used by Conradh na Gaeilge, the Irish language cultural organisation, for its annual convention....

he explicitly rejected it. "But we refuse to criminalise those who break the law in pursuit of legitimate political objectives. ... Sinn Féin is accused of recognising the Army Council of the IRA as the legitimate government of this island. That is not the case. ... do not believe that the Army Council is the government of Ireland. Such a government will only exist when all the people of this island elect it. Does Sinn Féin accept the institutions of this state as the legitimate institutions of this state? Of course we do."

As a result of this non-recognition, Sinn Féin had abstained from taking any of the seats they won in the British or Irish parliaments. At its 1986 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin delegates passed a resolution to amend the rules and constitution that would allow its members to sit in the Dublin parliament (Leinster House/Dáil Éireann). At this, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh is an Irish republican. He is a former chief of staff of the Irish Republican Army , former president of Sinn Féin and former president of Republican Sinn Féin.-Early life:...

led a small walkout, just as he and Sean Mac Stiofain had done sixteen years earlier with the creation of Provisional Sinn Féin. This minority, which rejected dropping the policy of abstentionism

Abstentionism

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in the election itself...

, now nominally distinguishes itself from Provisional Sinn Féin by using the name Republican Sinn Féin

Republican Sinn Féin

Republican Sinn Féin or RSF is an unregisteredAlthough an active movement, RSF is not registered as a political party in either Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland. minor political party operating in Ireland. It emerged in 1986 as a result of a split in Sinn Féin...

(or Sinn Féin Poblachtach), and maintains that they are the true Sinn Féin republicans.

Adams' leadership of Sinn Féin was supported by a Northern-based cadre that included people like Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness

Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness is an Irish Sinn Féin politician and the current deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. McGuinness was also the Sinn Féin candidate for the Irish presidential election, 2011. He was born in Derry, Northern Ireland....

. Over time, Adams and others pointed to Republican electoral successes in the early and mid-1980s, when hunger strikers Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands

Robert Gerard "Bobby" Sands was an Irish volunteer of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and member of the United Kingdom Parliament who died on hunger strike while imprisoned in HM Prison Maze....

and Kieran Doherty

Kieran Doherty

Kieran Doherty TD was an Irish republican hunger striker, Teachta Dála and a volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army ....

were elected to the British House of Commons and Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann is the lower house, but principal chamber, of the Oireachtas , which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann . It is directly elected at least once in every five years under the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote...

respectively, and they advocated that Sinn Féin become increasingly political and base its influence on electoral politics rather than paramilitarism. The electoral effects of this strategy were shown later by the election of Adams and McGuinness to the House of Commons.

Voice ban

Adams's prominence as an Irish Republican leader was increased by the ban on the media broadcast of his voice (the ban actually covered eleven republicanIrish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

and loyalist organisations, but in practice Adams was the only one prominent enough to appear regularly on TV). This ban was imposed by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

on 19 October 1988, the reason given being to "starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend" after the BBC interviewed Martin McGuinness

Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness is an Irish Sinn Féin politician and the current deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. McGuinness was also the Sinn Féin candidate for the Irish presidential election, 2011. He was born in Derry, Northern Ireland....

and Adams had been the focus of a row over an edition of After Dark, an intended Channel 4

Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British public-service television broadcaster which began working on 2 November 1982. Although largely commercially self-funded, it is ultimately publicly owned; originally a subsidiary of the Independent Broadcasting Authority , the station is now owned and operated by the Channel...

discussion programme which was never made.

A similar ban, known as Section 31, had been law in the Republic of Ireland since the 1970s. However, media outlets soon found ways around the ban, initially by the use of subtitles, but later and more commonly by the use of an actor reading his words over the images of him speaking. One actor who voiced Adams was Paul Loughran

Paul Loughran

Paul Loughran is a Northern Irish actor. He was educated at Methodist College Belfast. He is best known for portraying Butch Dingle in ITV Soap Opera Emmerdale in which his character died in a bus crash with friend Pete Collins. After that he appeared in many other Soaps such as Heartbeat...

.

This ban was lampooned in cartoons and satirical TV shows, such as Spitting Image

Spitting Image

Spitting Image is a British satirical puppet show that aired on the ITV network from 1984 to 1996. It was produced by Spitting Image Productions for Central Television. The series was nominated for 10 BAFTA Awards, winning one for editing in 1989....

, and in The Day Today

The Day Today

The Day Today is a surreal British parody of television current affairs programmes, broadcast in 1994, and created by the comedians Armando Iannucci and Chris Morris. It is an adaptation of the radio programme On the Hour, which was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 between 1991 and 1992...

and was criticised by freedom of speech

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship. The term freedom of expression is sometimes used synonymously, but includes any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used...

organisations and British media personalities, including BBC Director General John Birt and BBC foreign editor John Simpson. The ban was lifted by British Prime Minister John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

on 17 September 1994.

Moving into mainstream politics

Sinn Féin continued its policy of refusing to sit in the Westminster ParliamentParliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

even after Adams won the Belfast West

Belfast West (UK Parliament constituency)

Belfast West is a parliamentary constituency in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.-Boundaries:The seat was restored in 1922 when as part of the establishment of the devolved Stormont Parliament for Northern Ireland, the number of MPs in the Westminster Parliament was drastically cut...

constituency. He lost his seat to Joe Hendron

Joe Hendron

Joseph Gerard Hendron is a Northern Ireland politician, a member of the moderate Irish nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party ....

of the Social Democratic and Labour Party

Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party is a social-democratic, Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. Its basic party platform advocates Irish reunification, and the further devolution of powers while Northern Ireland remains part of the United Kingdom...

(SDLP) in the 1992 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1992

The United Kingdom general election of 1992 was held on 9 April 1992, and was the fourth consecutive victory for the Conservative Party. This election result was one of the biggest surprises in 20th Century politics, as polling leading up to the day of the election showed Labour under leader Neil...

, regaining it at the next election five years later

United Kingdom general election, 1997

The United Kingdom general election, 1997 was held on 1 May 1997, more than five years after the previous election on 9 April 1992, to elect 659 members to the British House of Commons. The Labour Party ended its 18 years in opposition under the leadership of Tony Blair, and won the general...

.

Under Adams, Sinn Féin appeared to move away from being a political voice of the Provisional IRA to becoming a professionally organised political party in both Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

and the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

.

SDLP leader John Hume

John Hume

John Hume is a former Irish politician from Derry, Northern Ireland. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize, with David Trimble....

, MP, identified the possibility that a negotiated settlement might be possible and began secret talks with Adams in 1988. These discussions led to unofficial contacts with the British Northern Ireland Office

Northern Ireland Office

The Northern Ireland Office is a United Kingdom government department responsible for Northern Ireland affairs. The NIO is led by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and is based in Northern Ireland at Stormont House.-Role:...

under the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, informally the Northern Ireland Secretary, is the principal secretary of state in the government of the United Kingdom with responsibilities for Northern Ireland. The Secretary of State is a Minister of the Crown who is accountable to the Parliament of...

, Peter Brooke

Peter Brooke

Peter Leonard Brooke, Baron Brooke of Sutton Mandeville, CH, PC , is a British politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet under Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and John Major, and was a Member of Parliament representing the Cities of London and Westminster from...

, and with the government of the Republic under Charles Haughey

Charles Haughey

Charles James "Charlie" Haughey was Taoiseach of Ireland, serving three terms in office . He was also the fourth leader of Fianna Fáil...

– although both governments maintained in public that they would not negotiate with "terrorists".

These talks provided the groundwork for what was later to be the Belfast Agreement

Belfast Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement , sometimes called the Stormont Agreement, was a major political development in the Northern Ireland peace process...

, as well as the milestone Downing Street Declaration

Downing Street Declaration

The Downing Street Declaration was a joint declaration issued on 15 December 1993 by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, John Major, and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland, Albert Reynolds at the British Prime Minister office in 10 Downing Street...

and the Joint Framework Document.

These negotiations led to the IRA ceasefire in August 1994. Irish Taoiseach

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government or prime minister of Ireland. The Taoiseach is appointed by the President upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas , and must, in order to remain in office, retain the support of a majority in the Dáil.The current Taoiseach is...

Albert Reynolds

Albert Reynolds

Albert Reynolds , served as Taoiseach of Ireland, serving one term in office from 1992 until 1994. He has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize...

, who had replaced Haughey and who had played a key role in the Hume/Adams dialogue through his Special Advisor Martin Mansergh

Martin Mansergh

Martin Mansergh is a former Irish Fianna Fáil politician and historian. He was a Teachta Dála for the Tipperary South constituency from May 2007 until his defeat at the general election in February 2011. He was previously a senator from 2002 to 2007.He has played a leading role in formulating...

, regarded the ceasefire as permanent. However, the slow pace of developments contributed in part to the (wider) political difficulties of the British government of John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

and the consequent reliance on Ulster Unionist Party

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

votes in the House of Commons, led the IRA to end its ceasefire and resume the campaign.

A re-instituted ceasefire later followed as part of the negotiations strategy, which saw teams from the British and Irish governments, the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP, Sinn Féin and representatives of loyalist paramilitary organizations, under the chairmanship of former United States Senator George Mitchell

George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell, Jr., is the former U.S. Special Envoy for Middle East Peace under the Obama administration. A Democrat, Mitchell was a United States Senator who served as the Senate Majority Leader from 1989 to 1995...

, produced the Belfast Agreement (also called the Good Friday Agreement as it was signed on Good Friday

Good Friday

Good Friday , is a religious holiday observed primarily by Christians commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his death at Calvary. The holiday is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum on the Friday preceding Easter Sunday, and may coincide with the Jewish observance of...

, 1998). Under the agreement, structures were created reflecting the Irish and British identities of the people of Ireland, with a British-Irish Council

British-Irish Council

The British–Irish Council is an international organisation established under the Belfast Agreement in 1998, and formally established on 2 December 1999 on the entry into force of the consequent legislation...

and a Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly

Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly is the devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and to appoint the Northern Ireland Executive...

created.

Articles 2 and 3 of the Republic's constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, which claimed sovereignty over all of Ireland, were reworded, and a power-sharing Executive Committee was provided for. As part of their deal, Sinn Féin agreed to abandon its abstentionist policy regarding a "six-county parliament", as a result taking seats in the new Stormont

Parliament Buildings (Northern Ireland)

The Parliament Buildings, known as Stormont because of its location in the Stormont area of Belfast is the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the Northern Ireland Executive...

-based Assembly and running the education and health and social services ministries in the power-sharing government.

On 15 August 1998, four months after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the Real IRA exploded a car bomb

Omagh bombing

The Omagh bombing was a car bomb attack carried out by the Real Irish Republican Army , a splinter group of former Provisional Irish Republican Army members opposed to the Good Friday Agreement, on Saturday 15 August 1998, in Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. Twenty-nine people died as a...

in Omagh

Omagh

Omagh is the county town of County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is situated where the rivers Drumragh and Camowen meet to form the Strule. The town, which is the largest in the county, had a population of 19,910 at the 2001 Census. Omagh also contains the headquarters of Omagh District Council and...

, County Tyrone

County Tyrone

Historically Tyrone stretched as far north as Lough Foyle, and comprised part of modern day County Londonderry east of the River Foyle. The majority of County Londonderry was carved out of Tyrone between 1610-1620 when that land went to the Guilds of London to set up profit making schemes based on...

, killing 31 people and injuring 220, from many communities. Breaking with tradition, Adams said in reaction to the bombing "I am totally horrified by this action. I condemn it without any equivocation whatsoever." Prior to this, Adams had maintained a policy of refusing to condemn IRA or their splinter groups' actions.

Opponents in Republican Sinn Féin accused Sinn Féin of "selling out" by agreeing to participate in what it called "partitionist

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland was the division of the island of Ireland into two distinct territories, now Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . Partition occurred when the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920...

assemblies" in the Republic and Northern Ireland. However, Gerry Adams insisted that the Belfast Agreement provided a mechanism to deliver a united Ireland by non-violent and constitutional means, much as Michael Collins

Michael Collins (Irish leader)

Michael "Mick" Collins was an Irish revolutionary leader, Minister for Finance and Teachta Dála for Cork South in the First Dáil of 1919, Director of Intelligence for the IRA, and member of the Irish delegation during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations. Subsequently, he was both Chairman of the...

had said of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of...

nearly 80 years earlier.

When Sinn Féin came to nominate its two ministers to the Northern Ireland Executive, for tactical reasons the party, like the SDLP and the Democratic Unionist Party

Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party is the larger of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland. Founded by Ian Paisley and currently led by Peter Robinson, it is currently the largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly and the fourth-largest party in the House of Commons of the...

(DUP), chose not to include its leader among its ministers. (When later the SDLP chose a new leader, it selected one of its ministers, Mark Durkan

Mark Durkan

Mark Durkan is an Irish nationalist politician in Northern Ireland who was leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party from 2001 to 2010.-Early life:...

, who then opted to remain in the Committee.)

Adams remains the President of Sinn Féin. In 2011 he succeeded Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin

Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin

Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin is a Sinn Féin politician from Ireland. He has been a Teachta Dála for the Cavan–Monaghan constituency since 1997 and was the parliamentary leader of Sinn Féin in Dáil Éireann from 1997–2011.-Biography:Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin was born in Monaghan in 1953. He was educated at St....

as Sinn Féin parliamentary leader in Dáil Éireann. Daithí McKay

Daithí McKay

Daithí McKay, MLA is an Irish republican politician. He is the Education spokesperson for Sinn Féin and the deputy chair of the Enterprise, Trade and Investment Committee in the Northern Irish Assembly...

is the head of the Sinn Féin group in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Adams was re-elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 8 March 2007, and on 26 March 2007, he met with DUP leader Ian Paisley

Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, PC is a politician and church minister in Northern Ireland. As the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party , he and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness were elected First Minister and deputy First Minister respectively on 8 May 2007.In addition to co-founding...

face-to-face for the first time, and the two came to an agreement regarding the return of the power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland.

In January 2009, Adams attended the United States presidential Inauguration of Barack Obama

Inauguration of Barack Obama

The inauguration of Barack Obama as the 44th President of the United States took place on Tuesday, January 20, 2009. The inauguration, which set a record attendance for any event held in Washington, D.C., marked the commencement of the four-year term of Barack Obama as President and Joe...

as a guest of US Congressman Richard Neal

Richard Neal

Richard Edmund Neal is the U.S. Representative for , serving since 1989. He is a member of the Democratic Party. He is a former city councilor and mayor of Springfield, Massachusetts....

.