Enola Gay

Encyclopedia

Enola Gay is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber

, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, mother of the pilot, then-Colonel

(later Brigadier General

) Paul Tibbets

. On August 6, 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb

as a weapon of war. The bomb, code-named "Little Boy

", was targeted at the city of Hiroshima

, Japan, and caused extensive destruction.

The Enola Gay gained additional attention in 1995 when the cockpit and nose section of the aircraft were exhibited during the bombing's 50th anniversary at the National Air and Space Museum

(NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution

in downtown Washington, D.C.

The exhibit was changed due to a controversy over original historical script displayed with the aircraft. Since 2003 the entire restored B-29 has been on display at NASM's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

.

(now Lockheed Martin

) at its Bellevue, Nebraska

, plant, at what is now known as Offutt Air Force Base

, and was one of fifteen B-29s with the "Silverplate

" modifications necessary to deliver atomic weapons, which included an extensively modified bomb bay with pneumatic doors, special propellors, modified engines and the deletion of protective armor and gun turrets. Enola Gay was personally selected by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr.

, commander of the 509th Composite Group, on May 9, 1945, while still on the assembly line

.

The aircraft was accepted by the USAAF on May 18, 1945 and assigned to the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy

, 509th Composite Group

. Crew B-9 (Captain Robert A. Lewis

, aircraft commander) took delivery of the bomber and flew it from Omaha to the 509th's base at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah

on June 14, 1945. Thirteen days later, the aircraft left Wendover for Guam

, where it received a bomb bay modification and flew to Tinian

on July 6th. It was originally given the victor number "12," but on August 1st was given the circle R tail markings of the 6th Bomb Group as a security measure and had its victor changed to "82" to avoid misidentification with actual 6th BG aircraft. During July of that year, after the bomber flew eight training missions and two combat missions to drop pumpkin bomb

s on industrial targets at Kobe

and Nagoya, Enola Gay was used on July 31st on a rehearsal flight for the actual mission. The partially-assembled Little Boy combat weapon L-11 was contained inside a 41” x 47” x 138” wood crate weighing 10000 pounds (4,535.9 kg) that was secured to the deck of the USS Indianapolis

. Unlike the six U-235 target discs, which were later flown to Tinian on three separate planes arriving July 28 and 29, the assembled projectile with the nine U-235 rings installed was shipped in a single lead-lined steel container weighing 300 pounds (136.1 kg) that was securely locked to brackets welded to the deck of Captain Charles McVay’s quarters. Both the L-11 and projectile were dropped off at Tinian on July 26, 1945.

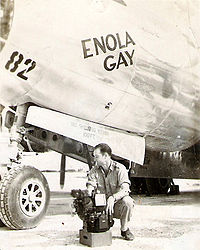

On August 5, 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets

On August 5, 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets

who assumed command of the aircraft, named the B-29 aircraft after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets (1893–1983), who had been named for the heroine of a novel

. According to Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan-Witts

, regularly assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission, and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of August 6th to see it painted with the now famous nose art. Tibbets himself, interviewed on Tinian later that day by war correspondents, confessed that he was a bit embarrassed at having attached his mother's name to such a fateful mission.

The Hiroshima mission

had been described by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts in Enola Gay book as tactically flawless, and Enola Gay returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare on the base. The Enola Gay was accompanied by two other B-29s, Necessary Evil which was used to carry scientific observers, and as a camera plane to photograph the explosion and effects of the bomb and The Great Artiste

instrumented for blast measurement.

The first atomic bombing was followed three days later by another B-29 (Bockscar

) (piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney) which dropped a second nuclear weapon, "Fat Man

", on Nagasaki. The Nagasaki mission, by contrast, had been described as tactically botched, although the mission had met its objectives. The crew encountered a number of problems in execution, and Bockscar

had very little fuel by the time it landed on Okinawa. On that mission, Enola Gay, flown by Crew B-10 (Capt. George Marquardt, aircraft commander, see Necessary Evil for crew details), was the weather reconnaissance aircraft for Kokura.

Enola Gays crew on August 6, 1945 consisted of 12 men. Only three, Tibbetts, Ferebee, and Parsons, knew the purpose of the mission.

Enola Gays crew on August 6, 1945 consisted of 12 men. Only three, Tibbetts, Ferebee, and Parsons, knew the purpose of the mission.

(Asterisks denote regular crewmen of the Enola Gay.)

, New Mexico

, on 8 November. On April 29, 1946, Enola Gay left Roswell as part of Operation Crossroads

and flew to Kwajalein

on May 1st. It was not chosen to make the test drop at Bikini Atoll

and left Kwajalein on July 1st, the date of the test, and reached Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Field

, California

, the next day.

The decision was made to preserve the Enola Gay, and on July 24, 1946, the aircraft was flown to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base

, Arizona

, in preparation for storage. On August 30, 1946, the title to the aircraft was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution

and the Enola Gay was removed from the USAAF inventory. From 1946 to 1961, the Enola Gay was put into temporary storage at a number of locations:

Restoration of the bomber began on December 5, 1984, at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility

in Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland

.

The propellers that were used on the bombing mission were later shipped to Texas A&M University

. One of these propellers was trimmed to 12½ ft for use in the university's Oran W. Nicks Low Speed Wind Tunnel. The lightweight aluminum variable pitch propeller is powered by a 1,250 kVA electric motor providing a wind speed up to 200 mph.

, when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War, was drafted by the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum

staff, and arranged around the restored Enola Gay.

Critics of the planned exhibit, especially those of the American Legion

and the Air Force Association

, charged that the exhibit focused too much attention on the Japanese casualties inflicted by the nuclear bomb, rather than on the motivations for the bombing or the discussion of the bomb's role in ending the World War II conflict with Japan. The exhibit brought to national attention many long-standing academic and political issues related to retrospective views of the bombings. As a result, after various failed attempts to revise the exhibit in order to meet the satisfaction of competing interest groups, the exhibit was canceled on January 30, 1995. Martin O. Harwit, Director of the National Air and Space Museum

, was compelled to resign over the controversy.

The forward fuselage did go on display on June 28, 1995. On July, 2nd three people were arrested for throwing ash and human blood on the aircraft's fuselage, following an earlier incident in which a protester had thrown red paint over the gallery's carpeting.

On May 18, 1998, the fuselage was returned to the Garber Facility for final restoration.

Restoration work began in 1984, and would eventually require 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

Restoration work began in 1984, and would eventually require 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

in Chantilly, Virginia

from March–June 2003, with the fuselage and wings reunited for the first time since 1960 on April 10, 2003 and assembly completed on August 18, 2003. The aircraft is currently at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, since the museum annex opened on December 15, 2003.

As a result of the earlier controversy, the signage around the aircraft provides only the same succinct technical data as is provided for other aircraft in the museum, without discussion of the controversial issues. The aircraft is shielded by various means to prevent a repetition of the vandalism that was attempted when it was first placed on display. A video analytics system was installed in 2005 and multiple surveillance cameras automatically generate an alarm when any person or object approaches the aircraft.

Bomber

A bomber is a military aircraft designed to attack ground and sea targets, by dropping bombs on them, or – in recent years – by launching cruise missiles at them.-Classifications of bombers:...

, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, mother of the pilot, then-Colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

(later Brigadier General

Brigadier General

Brigadier general is a senior rank in the armed forces. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries, usually sitting between the ranks of colonel and major general. When appointed to a field command, a brigadier general is typically in command of a brigade consisting of around 4,000...

) Paul Tibbets

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in the history of warfare. The bomb, code-named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima...

. On August 6, 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

as a weapon of war. The bomb, code-named "Little Boy

Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the codename of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, of the United States Army Air Forces. It was the first atomic bomb to be used as a weapon...

", was targeted at the city of Hiroshima

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture, and the largest city in the Chūgoku region of western Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It became best known as the first city in history to be destroyed by a nuclear weapon when the United States Army Air Forces dropped an atomic bomb on it at 8:15 A.M...

, Japan, and caused extensive destruction.

The Enola Gay gained additional attention in 1995 when the cockpit and nose section of the aircraft were exhibited during the bombing's 50th anniversary at the National Air and Space Museum

National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution holds the largest collection of historic aircraft and spacecraft in the world. It was established in 1976. Located in Washington, D.C., United States, it is a center for research into the history and science of aviation and...

(NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

in downtown Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

The exhibit was changed due to a controversy over original historical script displayed with the aircraft. Since 2003 the entire restored B-29 has been on display at NASM's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum 's annex at Washington Dulles International Airport in the Chantilly area of Fairfax County, Virginia, United States....

.

World War II

The Enola Gay (B-29-45-MO, AAF Serial Number 44-86292, victor number 82) was built by the Glenn L. Martin CompanyGlenn L. Martin Company

The Glenn L. Martin Company was an American aircraft and aerospace manufacturing company that was founded by the aviation pioneer Glenn L. Martin. The Martin Company produced many important aircraft for the defense of the United States and its allies, especially during World War II and the Cold War...

(now Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin is an American global aerospace, defense, security, and advanced technology company with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta in March 1995. It is headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, in the Washington Metropolitan Area....

) at its Bellevue, Nebraska

Bellevue, Nebraska

Bellevue is a city in Sarpy County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 50,137 at the 2010 census. Eight miles south of Omaha, Bellevue is part of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area. Originally settled in the 1830s, It was the first state capitol. Bellevue was incorporated in...

, plant, at what is now known as Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force installation near Omaha, and lies adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S...

, and was one of fifteen B-29s with the "Silverplate

Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project for the B-29 Superfortress to enable it to drop an atomic weapon, Silverplate eventually came to identify...

" modifications necessary to deliver atomic weapons, which included an extensively modified bomb bay with pneumatic doors, special propellors, modified engines and the deletion of protective armor and gun turrets. Enola Gay was personally selected by Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr.

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in the history of warfare. The bomb, code-named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima...

, commander of the 509th Composite Group, on May 9, 1945, while still on the assembly line

Assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process in which parts are added to a product in a sequential manner using optimally planned logistics to create a finished product much faster than with handcrafting-type methods...

.

The aircraft was accepted by the USAAF on May 18, 1945 and assigned to the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy

393d Bomb Squadron

The 393d Bomb Squadron is part of the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri.-History:Activated as a B-29 Superfortress squadron in early 1944; trained under Second Air Force. Training delayed as engineering flaws being worked out of the B-29...

, 509th Composite Group

509th Composite Group

The 509th Composite Group was a United States Army Air Forces unit created during World War II, and tasked with operational deployment of nuclear weapons...

. Crew B-9 (Captain Robert A. Lewis

Robert A. Lewis

Robert A. Lewis was a United States Army Air Forces Officer serving in the Pacific Theatre during World War II.Lewis grew up in Ridgefield Park, New Jersey and attended Ridgefield Park High School there, graduating in 1937....

, aircraft commander) took delivery of the bomber and flew it from Omaha to the 509th's base at Wendover Army Air Field, Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

on June 14, 1945. Thirteen days later, the aircraft left Wendover for Guam

Guam

Guam is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is one of five U.S. territories with an established civilian government. Guam is listed as one of 16 Non-Self-Governing Territories by the Special Committee on Decolonization of the United...

, where it received a bomb bay modification and flew to Tinian

Tinian

Tinian is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.-Geography:Tinian is about 5 miles southwest of its sister island, Saipan, from which it is separated by the Saipan Channel. It has a land area of 39 sq.mi....

on July 6th. It was originally given the victor number "12," but on August 1st was given the circle R tail markings of the 6th Bomb Group as a security measure and had its victor changed to "82" to avoid misidentification with actual 6th BG aircraft. During July of that year, after the bomber flew eight training missions and two combat missions to drop pumpkin bomb

Pumpkin bomb

Pumpkin bombs were conventional high explosive aerial bombs developed by the Manhattan Project and used by the United States Army Air Forces against Japan during World War II...

s on industrial targets at Kobe

Kobe

, pronounced , is the fifth-largest city in Japan and is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture on the southern side of the main island of Honshū, approximately west of Osaka...

and Nagoya, Enola Gay was used on July 31st on a rehearsal flight for the actual mission. The partially-assembled Little Boy combat weapon L-11 was contained inside a 41” x 47” x 138” wood crate weighing 10000 pounds (4,535.9 kg) that was secured to the deck of the USS Indianapolis

USS Indianapolis (CA-35)

USS Indianapolis was a of the United States Navy. She holds a place in history due to the circumstances of her sinking, which led to the greatest single loss of life at sea in the history of the U.S. Navy...

. Unlike the six U-235 target discs, which were later flown to Tinian on three separate planes arriving July 28 and 29, the assembled projectile with the nine U-235 rings installed was shipped in a single lead-lined steel container weighing 300 pounds (136.1 kg) that was securely locked to brackets welded to the deck of Captain Charles McVay’s quarters. Both the L-11 and projectile were dropped off at Tinian on July 26, 1945.

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in the history of warfare. The bomb, code-named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima...

who assumed command of the aircraft, named the B-29 aircraft after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets (1893–1983), who had been named for the heroine of a novel

Enola; or, Her fatal mistake

Enola; or, Her fatal mistake is an 1886 book written by Mary Young Ridenbaugh. It is notable for being the inspiration, indirectly, for the naming of the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber airplane which dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima...

. According to Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan-Witts

Max Morgan-Witts

Max Morgan-Witts is a British producer, director and author of Canadian origin.Morgan-Witts was a Director/Producer at Granada TV. He directed hundreds of popular television shows for Granada, including: 50 episodes of The Army Game, a forerunner of the American show Bilko and at the time Britain's...

, regularly assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission, and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of August 6th to see it painted with the now famous nose art. Tibbets himself, interviewed on Tinian later that day by war correspondents, confessed that he was a bit embarrassed at having attached his mother's name to such a fateful mission.

The Hiroshima mission

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

had been described by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts in Enola Gay book as tactically flawless, and Enola Gay returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare on the base. The Enola Gay was accompanied by two other B-29s, Necessary Evil which was used to carry scientific observers, and as a camera plane to photograph the explosion and effects of the bomb and The Great Artiste

The Great Artiste

The Great Artiste was a U.S. Army Air Forces Silverplate B-29 bomber , assigned to the 393rd Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group, that participated in the atomic bomb attacks on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Flown by 393rd commander Major Charles W...

instrumented for blast measurement.

The first atomic bombing was followed three days later by another B-29 (Bockscar

Bockscar

Bockscar, sometimes called Bock's Car or Bocks Car, is the name of the United States Army Air Forces B-29 bomber that dropped the "Fat Man" nuclear weapon over Nagasaki on 9 August 1945, the second atomic weapon used against Japan....

) (piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney) which dropped a second nuclear weapon, "Fat Man

Fat Man

"Fat Man" is the codename for the atomic bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, by the United States on August 9, 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons to be used in warfare to date , and its detonation caused the third man-made nuclear explosion. The name also refers more...

", on Nagasaki. The Nagasaki mission, by contrast, had been described as tactically botched, although the mission had met its objectives. The crew encountered a number of problems in execution, and Bockscar

Bockscar

Bockscar, sometimes called Bock's Car or Bocks Car, is the name of the United States Army Air Forces B-29 bomber that dropped the "Fat Man" nuclear weapon over Nagasaki on 9 August 1945, the second atomic weapon used against Japan....

had very little fuel by the time it landed on Okinawa. On that mission, Enola Gay, flown by Crew B-10 (Capt. George Marquardt, aircraft commander, see Necessary Evil for crew details), was the weather reconnaissance aircraft for Kokura.

Mission personnel

(Asterisks denote regular crewmen of the Enola Gay.)

- ColonelColonel (United States)In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

Paul W. Tibbets, Jr.Paul TibbetsPaul Warfield Tibbets, Jr. was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force, best known for being the pilot of the Enola Gay, the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in the history of warfare. The bomb, code-named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima...

(1915-2007) – Pilot and Aircraft commander - Captain Robert A. LewisRobert A. LewisRobert A. Lewis was a United States Army Air Forces Officer serving in the Pacific Theatre during World War II.Lewis grew up in Ridgefield Park, New Jersey and attended Ridgefield Park High School there, graduating in 1937....

(1917-1983) – Co-pilot; Enola Gays assigned aircraft commander* - MajorMajorMajor is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

Thomas FerebeeThomas FerebeeThomas W. Ferebee was the bombardier aboard the B-29 Superfortress, Enola Gay, that dropped the atomic bomb, "Little Boy", on Hiroshima in 1945.-Biography:...

(1918–2000) – BombardierBombardier (air force)A bombardier , in the United States Army Air Forces and United States Air Force, or a bomb aimer, in the Royal Air Force and other Commonwealth air forces, was the crewman of a bomber responsible for assisting the navigator in guiding the plane to a bombing target and releasing the aircraft's bomb...

; replaced regular crewman Donald Orrphin. - Captain Theodore "Dutch" Van KirkTheodore Van KirkTheodore Van Kirk is a former United States Army Air Force navigator. He is famous as the navigator of the Enola Gay when it dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima...

(1921-) – NavigatorFlight officerThe title flight officer was a military rank used by the United States Armed Forces where it was an air force warrant officer rank. It was also an air force rank in several Commonwealth nations where it was used for female officers and was equivalent to the rank of flight lieutenant... - U.S. Navy Captain William S. "Deak" ParsonsWilliam Sterling ParsonsRear Admiral William Sterling "Deak" Parsons was a naval officer who worked as an ordnance expert on the Manhattan Project during World War II...

(1901–1953) – Weaponeer and bomb commander. - Lieutenant Jacob BeserJacob BeserJacob Beser was a lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces who served during World War II. Beser was the radar specialist aboard the Enola Gay on August 6, 1945, when it dropped the "Little Boy" atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Three days later, Beser was aboard Bock's Car when "Fat Man" was...

(1921–1992) – Radar countermeasuresElectronic countermeasuresAn electronic countermeasure is an electrical or electronic device designed to trick or deceive radar, sonar or other detection systems, like infrared or lasers. It may be used both offensively and defensively to deny targeting information to an enemy...

(also the only man to fly on both of the nuclear bombing aircraft) - Second Lieutenant Morris R. JeppsonMorris R. JeppsonMorris Richard Jeppson was born in Logan, Utah and was a Second Lieutenant in the Army Air Forces during World War II. He served as assistant weaponeer on the Enola Gay, which dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945.-Early life:Jeppson studied physics at the University...

(1922–2010) – Assistant weaponeer - Technical Sergeant George R. "Bob" CaronGeorge R. "Bob" CaronTechnical Sergeant George Robert "Bob" Caron was the tail gunner, the only defender of the twelve crewmen, aboard the B-29 Enola Gay during the historic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan on 6 August 1945...

(1919-1995) – Tail gunner* - Technical Sergeant Wyatt E. Duzenberry – Flight engineerFlight engineerFlight engineers work in three types of aircraft: fixed-wing , rotary wing , and space flight .As airplanes became even larger requiring more engines and complex systems to operate, the workload on the two pilots became excessive during certain critical parts of the flight regime, notably takeoffs...

* - Sergeant Joe S. Stiborik (1914-1984) – RadarRadarRadar is an object-detection system which uses radio waves to determine the range, altitude, direction, or speed of objects. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations, and terrain. The radar dish or antenna transmits pulses of radio...

operator* - Sergeant Robert H. Shumard (1920-1967) – Assistant flight engineer*

- Private First Class Richard H. Nelson (1925-2003) – VHF radioRadioRadio is the transmission of signals through free space by modulation of electromagnetic waves with frequencies below those of visible light. Electromagnetic radiation travels by means of oscillating electromagnetic fields that pass through the air and the vacuum of space...

operator*

Subsequent history

On November 6, 1945, Lewis flew the Enola Gay back to the United States, arriving at the 509th's new base at Roswell Army Air FieldWalker Air Force Base

Walker Air Force Base is a closed United States Air Force base located three miles south of the central business district of Roswell, a city in Chaves County, New Mexico, US...

, New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

, on 8 November. On April 29, 1946, Enola Gay left Roswell as part of Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. It was the first test of a nuclear weapon after the Trinity nuclear test in July 1945...

and flew to Kwajalein

Kwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll , is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands . The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island. English-speaking residents of the U.S...

on May 1st. It was not chosen to make the test drop at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll is an atoll, listed as a World Heritage Site, in the Micronesian Islands of the Pacific Ocean, part of Republic of the Marshall Islands....

and left Kwajalein on July 1st, the date of the test, and reached Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Field

Travis Air Force Base

Travis Air Force Base is a United States Air Force air base under the operational control of the Air Mobility Command , located three miles east of the central business district of Fairfield, in Solano County, California, United States. The base is named for Brigadier General Robert F...

, California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, the next day.

The decision was made to preserve the Enola Gay, and on July 24, 1946, the aircraft was flown to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base

Davis–Monthan Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located within the city limits, and approximately south-southeast of downtown, Tucson, Arizona....

, Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

, in preparation for storage. On August 30, 1946, the title to the aircraft was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

and the Enola Gay was removed from the USAAF inventory. From 1946 to 1961, the Enola Gay was put into temporary storage at a number of locations:

- September 1, 1946: Davis-Monthan AFB.

- July 3, 1949: Orchard Place Air FieldO'Hare International AirportChicago O'Hare International Airport , also known as O'Hare Airport, O'Hare Field, Chicago Airport, Chicago International Airport, or simply O'Hare, is a major airport located in the northwestern-most corner of Chicago, Illinois, United States, northwest of the Chicago Loop...

, Park Ridge, IllinoisPark Ridge, Illinois-Climate:-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 37,775 people, 14,219 households, and 10,465 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,374.6 people per square mile . There were 14,646 housing units at an average density of 2,083.8 per square mile...

, flown there by Brig Gen Tibbets for acceptance by the Smithsonian. - January 12, 1952: Pyote Air Force BasePyote Air Force BasePyote Air Force Base was a World War II United States Army Air Forces training airbase. It was on a mile from the town of Pyote, Texas on Interstate 20, twenty miles west of Monahans and just south of U.S...

, Texas, moved after O'Hare International AirportO'Hare International AirportChicago O'Hare International Airport , also known as O'Hare Airport, O'Hare Field, Chicago Airport, Chicago International Airport, or simply O'Hare, is a major airport located in the northwestern-most corner of Chicago, Illinois, United States, northwest of the Chicago Loop...

's location was announced. - December 2, 1953: Andrews Air Force BaseAndrews Air Force BaseJoint Base Andrews is a United States military facility located in Prince George's County, Maryland. The facility is under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force 11th Wing, Air Force District of Washington ....

, Maryland. - August 10, 1960: disassembly at Andrews AFB begun by personnel of the Smithsonian.

- July 21, 1961: components transported to the Smithsonian storage facility at Suitland, Maryland.

Restoration of the bomber began on December 5, 1984, at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility

Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility

The Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility is located in Suitland, Maryland, USA. The facility, also nicknamed "Silver Hill", is where the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum restores aircraft, spacecraft, and other artifacts.It is named in honor of...

in Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland

Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland

Suitland-Silver Hill is a census-designated place in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. The census area include separate unincorporated communities of Silver Hill and Suitland, and other smaller communities. The population was 33,515 at the 2000 census...

.

The propellers that were used on the bombing mission were later shipped to Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University is a coeducational public research university located in College Station, Texas . It is the flagship institution of the Texas A&M University System. The sixth-largest university in the United States, A&M's enrollment for Fall 2011 was over 50,000 for the first time in school...

. One of these propellers was trimmed to 12½ ft for use in the university's Oran W. Nicks Low Speed Wind Tunnel. The lightweight aluminum variable pitch propeller is powered by a 1,250 kVA electric motor providing a wind speed up to 200 mph.

Exhibition controversy

Enola Gay became the center of a controversy at the Smithsonian InstitutionSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

, when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War, was drafted by the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum

National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution holds the largest collection of historic aircraft and spacecraft in the world. It was established in 1976. Located in Washington, D.C., United States, it is a center for research into the history and science of aviation and...

staff, and arranged around the restored Enola Gay.

Critics of the planned exhibit, especially those of the American Legion

American Legion

The American Legion is a mutual-aid organization of veterans of the United States armed forces chartered by the United States Congress. It was founded to benefit those veterans who served during a wartime period as defined by Congress...

and the Air Force Association

Air Force Association

The Air Force Association is an independent, 501 non-profit, civilian education organization, headquartered in Arlington, Virginia...

, charged that the exhibit focused too much attention on the Japanese casualties inflicted by the nuclear bomb, rather than on the motivations for the bombing or the discussion of the bomb's role in ending the World War II conflict with Japan. The exhibit brought to national attention many long-standing academic and political issues related to retrospective views of the bombings. As a result, after various failed attempts to revise the exhibit in order to meet the satisfaction of competing interest groups, the exhibit was canceled on January 30, 1995. Martin O. Harwit, Director of the National Air and Space Museum

National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution holds the largest collection of historic aircraft and spacecraft in the world. It was established in 1976. Located in Washington, D.C., United States, it is a center for research into the history and science of aviation and...

, was compelled to resign over the controversy.

The forward fuselage did go on display on June 28, 1995. On July, 2nd three people were arrested for throwing ash and human blood on the aircraft's fuselage, following an earlier incident in which a protester had thrown red paint over the gallery's carpeting.

On May 18, 1998, the fuselage was returned to the Garber Facility for final restoration.

Complete restoration and display

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center is the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum 's annex at Washington Dulles International Airport in the Chantilly area of Fairfax County, Virginia, United States....

in Chantilly, Virginia

Chantilly, Virginia

Chantilly is an unincorporated community located in western Fairfax County and southeastern Loudoun County of Northern Virginia. Recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau as a census designated place , the community population was 23,039 as of the 2010 census -- down from 41,041 in 2000, due to the...

from March–June 2003, with the fuselage and wings reunited for the first time since 1960 on April 10, 2003 and assembly completed on August 18, 2003. The aircraft is currently at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, since the museum annex opened on December 15, 2003.

As a result of the earlier controversy, the signage around the aircraft provides only the same succinct technical data as is provided for other aircraft in the museum, without discussion of the controversial issues. The aircraft is shielded by various means to prevent a repetition of the vandalism that was attempted when it was first placed on display. A video analytics system was installed in 2005 and multiple surveillance cameras automatically generate an alarm when any person or object approaches the aircraft.

External links

- History of Enola Gay co-pilot Robert A. Lewis's mushroom cloud sculpture

- Annotated bibliography for the Enola Gay from the Alsos Digital Library

- The Smithsonian's site on Enola Gay' includes links to crew lists and other details

- Eyewitnesses to Hiroshima, Time magazine, 1 August 2005

- "Inside the Enola Gay", Air & Space, May 18, 2010