Executive Magistrates of the Roman Republic

Encyclopedia

The Executive Magistrates of the Roman Republic were officials of the ancient Roman Republic

(c. 510 BC – 44 BC), elected by the People of Rome

. Ordinary magistrate

s (magistratus) were divided into several ranks according to their role and the power they wielded: Censors, Consul

s (who functioned as the regular head of state), Praetor

s, Curule Aediles, and finally Quaestor

. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto

) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. By definition, Plebeian Tribunes

and Plebeian Aediles

were technically not magistrates as they were elected only by the Plebeians, but no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions. Dictator

was an extraordinary magistrate normally elected in times of emergency (usually military) for a short period of time. During this period, the Dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate.

s (magistratus) were elected by the People of Rome

, which consisted of Plebeians (commoners) and Patricians (aristocrats). Each magistrate was vested with a degree of power, called "major powers" or maior potestas. Dictators

had more "major powers" than any other magistrate, and thus they outranked all other magistrates; but were originally intended only to be a temporary tool for times of state emergency. Thereafter in descending order came the Censor (who, while the highest ranking ordinary magistrate by virtue of his prestige, held little real power), the Consul

, the Praetor

, the Curule Aedile, and the Quaestor

. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto

) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. If this obstruction occurred between two magistrates of equal rank, such as two Praetors, then it was called par potestas (negation of powers). To prevent this, magistrates used a principle of alteration, assigned responsibilities by lot or seniority, or gave certain magistrates control over certain functions. If this obstruction occurred against a magistrate of a lower rank, then it was called intercessio, where the magistrate literally interposed his higher rank to obstruct the lower ranking magistrate. By definition, Plebeian Tribunes

and Plebeian Aediles

were technically not magistrates since they were elected only by the Plebeians. As such, no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions.

) on any individual magistrate. The most important power was imperium

, which was held by Consuls (the chief magistrates) and by Praetors (the second highest ranking ordinary magistrate). Defined narrowly, imperium simply gave a magistrate the authority to command a military force. Defined more broadly, however, imperium gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military, diplomatic, civil, or otherwise). A magistrate's imperium was at its apex while the magistrate was abroad. While the magistrate was in the city of Rome itself, however, he had to completely surrender his imperium, so that liberty (libertas) was maximized. Magistrates with imperium sat in a Curule Chair

, and were attended by Lictors (bodyguards) who carried axes called Fasces

which symbolized the power of the state to punish and to execute. Only a magistrate with imperium could wear a bordered toga, or be awarded a triumph

.

All magistrates had the power of Coercion

All magistrates had the power of Coercion

(coercitio), which was used by magistrates to maintain public order. A magistrate had many ways with which to enforce this power. Examples include flogging, imprisonment, fines, mandating pledges and oaths, enslavement, banishment, and sometimes even the destruction of a person's house. While in Rome, all citizens had an absolute protection against Coercion. This protection was called "Provocatio" (see below), which allowed any citizen to appeal any punishment. However, the power of Coercion outside the city of Rome was absolute. Magistrates also had both the power and the duty to look for omens from the Gods (auspicia), which could be used to obstruct political opponents. By claiming to witness an omen, a magistrate could justify the decision to end a legislative or senate meeting, or the decision to veto a colleague. While the magistrates had access to oracular documents, the Sibylline books

, they rarely consulted with these books, and even then, only after seeing an omen. All senior magistrates (Consuls, Praetors, Censors, and Plebeian Tribunes) were required to actively look for omen

s (auspicia impetrativa); simply having omens thrust upon them (auspicia oblativa) was generally not adequate. Omens could be discovered while observing the heavens, while studying the flight of birds, or while studying the entrails of sacrificed animals. When a magistrate believed that he had witnessed such an omen, he usually had an a priest

(augur

) interpret the omen. A magistrate was required to look for omens while presiding over a legislative or senate meeting, and while preparing for a war.

One check over a magistrate's power was collegiality (collega), which required that each magisterial office be held concurrently by at least two people. For example, two Consuls always served together. The check on the magistrate's power of Coercion was Provocatio, which was an early form of due process (habeas corpus

). Any Roman citizen had the absolute right to appeal any ruling by a magistrate to a Plebeian Tribune. In this case, the citizen would cry "provoco ad populum", which required the magistrate to wait for a Tribune to intervene, and make a ruling. Sometimes, the case was brought before the College of Tribunes, and sometimes before the Plebeian Council

(popular assembly). Since no Tribune could retain his powers outside of the city of Rome, the power of Coercion here was absolute. An additional check over a magistrate's power was that of Provincia, which required a division of responsibilities.

Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he had to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Since this did create problems for some magistrates (in particular, Consuls and Praetors), these magistrates occasionally had their imperium "prorogued" (prorogare

), which allowed them to retain the powers of the office as a Promagistrate

. The result was that private citizens ended up with Consular and Praetorian imperium, without actually holding either office. Often, they used this power to act as provincial governors.

was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Two Consuls were elected for an annual term (from January through December) by the assembly of Roman soldiers, the Century Assembly

. After they were elected, they were granted imperium

powers by the assembly. If a Consul died before his term ended, another Consul (the consul suffectus), was elected to complete the original Consular term. Throughout the year, one Consul was superior in rank to the other Consul. This ranking flipped every month, between the two Consuls. Once a Consul's term ended, he held the honorary title of consulare for the rest of his time in the senate, and had to wait for ten years before standing for reelection to the Consulship. Consuls had supreme power in both civil and military matters, which was due, in part, to the fact that they held the highest ordinary grade of imperium (command) powers. While in the city of Rome, the Consul was the head of the Roman government. While components of public administration were delegated to other magistrates, the management of the government was under the ultimate authority of the Consul. The Consuls presided over the Roman Senate

and the Roman assemblies

, and had the ultimate responsibility to enforce policies and laws enacted by both institutions. The Consul was the chief diplomat, carried out business with foreign nations, and facilitated interactions between foreign ambassadors and the senate. Upon an order by the senate, the Consul was responsible for raising and commanding an army. While the Consuls had supreme military authority, they had to be provided with financial resources by the Roman Senate while they were commanding their armies. While abroad, the Consul had absolute power over his soldiers, and over any Roman province.

The Praetors administered civil law

and commanded provincial armies, and, eventually, began to act as chief judges over the courts. Praetors usually stood for election with the Consuls before the assembly of the soldiers, the Century Assembly. After they were elected, they were granted imperium powers by the assembly. In the absence of both senior and junior Consuls from the city, the Urban Praetor governed Rome, and presided over the Roman Senate and Roman assemblies

. Other Praetors had foreign affairs-related responsibilities, and often acted as governors of the provinces. Since Praetors held imperium powers, they could command an army.

Every five years, two Censors were elected for an eighteen month term. Since the Censorship was the most prestigious of all offices, usually only former Consuls were elected to it. Censors were elected by the assembly of Roman Soldiers, the Century Assembly, usually after the new Consuls and Praetors for the year began their term. After the Censors had been elected, the Century Assembly granted the new Censors Censorial power. Censors did not have imperium powers, and they were not accompanied by any lictor

Every five years, two Censors were elected for an eighteen month term. Since the Censorship was the most prestigious of all offices, usually only former Consuls were elected to it. Censors were elected by the assembly of Roman Soldiers, the Century Assembly, usually after the new Consuls and Praetors for the year began their term. After the Censors had been elected, the Century Assembly granted the new Censors Censorial power. Censors did not have imperium powers, and they were not accompanied by any lictor

s. In addition, they did not have the power to convene the Roman Senate or Roman assemblies. Technically they outranked all other ordinary magistrates (including Consuls and Praetors). This ranking, however, was solely a result of their prestige, rather than any real power they had. Since the office could be easily abused (as a result of its power over every ordinary citizen), only former Consuls (usually Patrician Consuls) were elected to the office. This is what gave the office its prestige. Their actions could not be vetoed by any magistrate other than a Plebeian Tribune, or a fellow Censor. No other ordinary magistrate could veto a Censor because no ordinary magistrate technically outranked a Censor. Tribunes, by virtue of their sacrosanctity as the representatives of the people, could veto anything or anyone. Censors usually did not have to act in unison, but if a Censor wanted to reduce the status of a citizen in a census, he had to act in unison with his colleague.

Censors could enroll citizens in the senate, or purge them from the senate. A Censor had the ability to fine a citizen, or to sell his property, which was often a punishment for either evading the census or having filed a fraudulent registration. Other actions that could result in a Censorial punishment were the poor cultivation of land

, cowardice or disobedience in the army, dereliction of civil duties, corruption, or debt. A Censor could reassign a citizen to a different Tribe

(a civil unit of division), or place a punitive mark (nota) besides a man's name on the register. Later, a law (one of the Leges Clodiae

or "Clodian Laws") allowed a citizen to appeal a Censorial nota. Once a census was complete, a purification ceremony (the lustrum

) was performed by a Censor, which typically involved prayers for the upcoming five years. This was a religious ceremony that acted as the certification of the census, and was performed before the Century Assembly. Censors had several other duties as well, including the management of public contracts and the payment of individuals doing contract work for the state. Any act by the Censor that resulted in an expenditure of public money

required the approval of the senate.

Aedile

s were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, and often assisted the higher magistrates. The office was not on the cursus honorum

, and therefore did not mark the beginning of a political career. Every year, two Curule Aedile

s and two Plebeian Aediles were elected. The Tribal Assembly

, while under the presidency of a higher magistrate (either a Consul or Praetor), elected the two Curule Aediles. While they had a curule chair, they did not have lictors, and thus they had no power of coercion. The Plebeian Council

(principal popular assembly), under the presidency of a Plebeian Tribune

, elected the two Plebeian Aediles. Aediles had wide ranging powers over day-to-day affairs inside the city of Rome, and over the maintenance of public order. They had the power over public games and shows, and over the markets. They also had the power to repair and preserve temples, sewers and aqueducts, to maintain public records, and to issue edicts. Any expenditure of public funds, by either a Curule Aedile or a Plebeian Aedile, had to be authorized by the senate.

The office of Quaestor

was considered to be the lowest ranking of all major political offices. Quaestors were elected by the Tribal Assembly, and the assignment of their responsibilities were settled by lot. Magistrates often chose which Quaestor accompanied them abroad, and these Quaestors often functioned as personal secretaries responsible for the allocation of money, including army pay. Urban Quaestors had several important responsibilities, such as the management of the public treasury, (the aerarium Saturni) where they monitored all items going into, and coming out of, the treasury. In addition, they often spoke publicly about the balances available in the treasury. The Quaestors could only issue public money for a particular purpose if they were authorized to do so by the senate. The Quaestors were assisted by scribe

s, who handled the actual accounting for the treasury. The treasury was a repository for documents, as well as for money. The texts of enacted statutes and decrees of the Roman Senate were deposited in the treasury under the supervision of the Quaestors.

and Plebeian Aediles

were elected by the Plebeians (commoners) in the Plebeian Council

, rather than by all of the People of Rome

(Plebeians and the aristocratic Patrician class), they were technically not magistrates. While the term "Plebeian Magistrate" (magistratus plebeii) has been used as an approximation, it is technically a contradiction. The Plebeian Aedile functioned as the Tribune's assistant, and often performed similar duties as did the Curule Aediles (discussed above). In time, however, the differences between the Plebeian Aediles and the Curule Aediles disappeared.

Since the Tribunes were considered to be the embodiment of the Plebeians, they were sacrosanct

Since the Tribunes were considered to be the embodiment of the Plebeians, they were sacrosanct

. Their sacrosanctity was enforced by a pledge, taken by the Plebeians, to kill any person who harmed or interfered with a Tribune during his term of office. All of the powers of the Tribune derived from their sacrosanctity. One obvious consequence of this sacrosanctity was the fact that it was considered a capital offense to harm a Tribune, to disregard his veto, or to interfere with a Tribune. The sacrosanctity of a Tribune (and thus all of his legal powers) were only in effect so long as that Tribune was within the city of Rome. If the Tribune was abroad, the Plebeians in Rome could not enforce their oath to kill any individual who harmed or interfered with the Tribune. Since Tribunes were technically not magistrates, they had no magisterial powers ("major powers" or maior potestas), and thus could not rely on such powers to veto. Instead, they relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct. If a magistrate, an assembly or the senate did not comply with the orders of a Tribune, the Tribune could 'interpose the sacrosanctity of his person' (intercessio) to physically stop that particular action. Any resistance against the Tribune was tantamount to a violation of his sacrosanctity, and thus was considered a capital offense. Their lack of magisterial powers made them independent of all other magistrates, which also meant that no magistrate could veto a Tribune.

Tribunes could use their sacrosanctity to order the use of capital punishment against any person who interfered with their duties. Tribunes could also use their sacrosanctity as protection when physically manhandling an individual, such as when arrest

ing someone. On a couple of rare occasions (such as during the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus

), a Tribune might use a form of blanket obstruction, which could involve a broad veto over all governmental functions. While a Tribune could veto any act of the senate, the assemblies, or the magistrates, he could only veto the act, and not the actual measure. Therefore, he had to physically be present when the act was occurring. As soon as that Tribune was no longer present, the act could be completed as if there had never been a veto.

Tribunes, the only true representatives of the people, had the authority to enforce the right of Provocatio, which was a theoretical guarantee of due process, and a precursor to our own habeas corpus. If a magistrate was threatening to take action against a citizen, that citizen could yell "provoco ad populum", which would appeal the magistrate's decision to a Tribune. A Tribune had to assess the situation, and give the magistrate his approval before the magistrate could carry out the action. Sometimes the Tribune brought the case before the College of Tribunes or the Plebeian Council for a trial. Any action taken in spite of a valid provocatio was on its face illegal.

In times of emergency (military or otherwise), a Roman Dictator

In times of emergency (military or otherwise), a Roman Dictator

(magister populi or "Master of the Nation") was appointed for a six month term. The Dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate. While the Consul Cicero

and the contemporary historian Livy

do mention the military uses of the dictatorship, others, such as the contemporary historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus

, mention its use for the purposes of maintaining order during times of Plebeian unrest. For a Dictator to be appointed, the Roman Senate had to pass a decree (a senatus consultum), authorizing a Roman Consul

to nominate a Dictator, who then took office immediately. Often the Dictator resigned his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved. Ordinary magistrates (such as Consuls and Praetors) retained their offices, but lost their independence and became agents of the Dictator. If they disobeyed the Dictator, they could be forced out of office. While a Dictator could ignore the right of Provocatio, that right, as well as the Plebeian Tribune's independence, theoretically still existed during a Dictator's term. A Dictator's power was equivalent to that of the power of the two Consuls exercised conjointly, without any checks on their power by any other organ of government. Thus, Dictatorial appointments were tantamount to a six month restoration of the monarchy, with the Dictator taking the place of the old Roman King. This is why, for example, each Consul was accompanied by six lictors, whereas the Dictator (as the Roman King before him) was accompanied by twelve lictors.

Each Dictator appointed a Master of the Horse

(magister equitum or Master of the Knights), to serve as his most senior lieutenant

. The Master of the Horse had constitutional command authority (imperium

) equivalent to a Praetor

, and often, when they authorized the appointment of a Dictator, the senate specified who was to be the Master of the Horse. In many respects, he functioned more as a parallel magistrate (like an inferior co-Consul) than he did as a direct subordinate. Whenever a Dictator's term ended, the term of his Master of the Horse ended as well. Often, the Dictator functioned principally as the master of the infantry (and thus the legions

), while the Master of the Horse (as the name implies) functioned as the master of the cavalry. The Dictator, while not elected by the people, was technically a magistrate since he was nominated by an elected Consul. The Master of the Horse was also technically a magistrate, since he was nominated by the Dictator. Thus, both of these magistrates were referred to as "Extraordinary Magistrates".

The last ordinary Dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the senatus consultum ultimum

("ultimate decree of the senate") which suspended civil government, and declared something analogous to martial law

. It declared "videant consules ne res publica detrimenti capiat" ("let the Consuls see to it that the state suffer no harm") which, in effect, vested the Consuls with dictatorial powers. There were several reasons for this change. Up until 202 BC, Dictators were often appointed to fight Plebeian unrest. In 217 BC, a law was passed that gave the popular assemblies the right to nominate Dictators. This, in effect, eliminated the monopoly that the aristocracy

had over this power. In addition, a series of laws were passed, which placed additional checks on the power of the Dictator.

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

(c. 510 BC – 44 BC), elected by the People of Rome

SPQR

SPQR is an initialism from a Latin phrase, Senatus Populusque Romanus , referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic, and used as an official emblem of the modern day comune of Rome...

. Ordinary magistrate

Magistrate

A magistrate is an officer of the state; in modern usage the term usually refers to a judge or prosecutor. This was not always the case; in ancient Rome, a magistratus was one of the highest government officers and possessed both judicial and executive powers. Today, in common law systems, a...

s (magistratus) were divided into several ranks according to their role and the power they wielded: Censors, Consul

Consul

Consul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

s (who functioned as the regular head of state), Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

s, Curule Aediles, and finally Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. By definition, Plebeian Tribunes

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

and Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

were technically not magistrates as they were elected only by the Plebeians, but no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions. Dictator

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

was an extraordinary magistrate normally elected in times of emergency (usually military) for a short period of time. During this period, the Dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate.

Ranks

The magistrateMagistrate

A magistrate is an officer of the state; in modern usage the term usually refers to a judge or prosecutor. This was not always the case; in ancient Rome, a magistratus was one of the highest government officers and possessed both judicial and executive powers. Today, in common law systems, a...

s (magistratus) were elected by the People of Rome

SPQR

SPQR is an initialism from a Latin phrase, Senatus Populusque Romanus , referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic, and used as an official emblem of the modern day comune of Rome...

, which consisted of Plebeians (commoners) and Patricians (aristocrats). Each magistrate was vested with a degree of power, called "major powers" or maior potestas. Dictators

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

had more "major powers" than any other magistrate, and thus they outranked all other magistrates; but were originally intended only to be a temporary tool for times of state emergency. Thereafter in descending order came the Censor (who, while the highest ranking ordinary magistrate by virtue of his prestige, held little real power), the Consul

Consul

Consul was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic and an appointive office under the Empire. The title was also used in other city states and also revived in modern states, notably in the First French Republic...

, the Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

, the Curule Aedile, and the Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. If this obstruction occurred between two magistrates of equal rank, such as two Praetors, then it was called par potestas (negation of powers). To prevent this, magistrates used a principle of alteration, assigned responsibilities by lot or seniority, or gave certain magistrates control over certain functions. If this obstruction occurred against a magistrate of a lower rank, then it was called intercessio, where the magistrate literally interposed his higher rank to obstruct the lower ranking magistrate. By definition, Plebeian Tribunes

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

and Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

were technically not magistrates since they were elected only by the Plebeians. As such, no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions.

Powers

Only the Roman citizens (both Plebeians and Patricians) had the right to confer magisterial powers (potestasPotestas

Potestas is a Latin word meaning power or faculty. It is an important concept in Roman Law.-Origin of the concept:The idea of potestas originally referred to the power, through coercion, of a Roman magistrate to promulgate edicts, give action to litigants, etc. This power, in Roman political and...

) on any individual magistrate. The most important power was imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

, which was held by Consuls (the chief magistrates) and by Praetors (the second highest ranking ordinary magistrate). Defined narrowly, imperium simply gave a magistrate the authority to command a military force. Defined more broadly, however, imperium gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military, diplomatic, civil, or otherwise). A magistrate's imperium was at its apex while the magistrate was abroad. While the magistrate was in the city of Rome itself, however, he had to completely surrender his imperium, so that liberty (libertas) was maximized. Magistrates with imperium sat in a Curule Chair

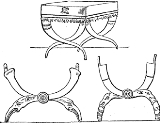

Curule chair

In the Roman Republic, and later the Empire, the curule seat was the chair upon which senior magistrates or promagistrates owning imperium were entitled to sit, including dictators, masters of the horse, consuls, praetors, censors, and the curule aediles...

, and were attended by Lictors (bodyguards) who carried axes called Fasces

Fasces

Fasces are a bundle of wooden sticks with an axe blade emerging from the center, which is an image that traditionally symbolizes summary power and jurisdiction, and/or "strength through unity"...

which symbolized the power of the state to punish and to execute. Only a magistrate with imperium could wear a bordered toga, or be awarded a triumph

Roman triumph

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the military achievement of an army commander who had won great military successes, or originally and traditionally, one who had successfully completed a foreign war. In Republican...

.

Coercion

Coercion is the practice of forcing another party to behave in an involuntary manner by use of threats or intimidation or some other form of pressure or force. In law, coercion is codified as the duress crime. Such actions are used as leverage, to force the victim to act in the desired way...

(coercitio), which was used by magistrates to maintain public order. A magistrate had many ways with which to enforce this power. Examples include flogging, imprisonment, fines, mandating pledges and oaths, enslavement, banishment, and sometimes even the destruction of a person's house. While in Rome, all citizens had an absolute protection against Coercion. This protection was called "Provocatio" (see below), which allowed any citizen to appeal any punishment. However, the power of Coercion outside the city of Rome was absolute. Magistrates also had both the power and the duty to look for omens from the Gods (auspicia), which could be used to obstruct political opponents. By claiming to witness an omen, a magistrate could justify the decision to end a legislative or senate meeting, or the decision to veto a colleague. While the magistrates had access to oracular documents, the Sibylline books

Sibylline Books

The Sibylline Books or Libri Sibyllini were a collection of oracular utterances, set out in Greek hexameters, purchased from a sibyl by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, and consulted at momentous crises through the history of the Republic and the Empire...

, they rarely consulted with these books, and even then, only after seeing an omen. All senior magistrates (Consuls, Praetors, Censors, and Plebeian Tribunes) were required to actively look for omen

Omen

An omen is a phenomenon that is believed to foretell the future, often signifying the advent of change...

s (auspicia impetrativa); simply having omens thrust upon them (auspicia oblativa) was generally not adequate. Omens could be discovered while observing the heavens, while studying the flight of birds, or while studying the entrails of sacrificed animals. When a magistrate believed that he had witnessed such an omen, he usually had an a priest

Priest

A priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities...

(augur

Augur

The augur was a priest and official in the classical world, especially ancient Rome and Etruria. His main role was to interpret the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds: whether they are flying in groups/alone, what noises they make as they fly, direction of flight and what kind of...

) interpret the omen. A magistrate was required to look for omens while presiding over a legislative or senate meeting, and while preparing for a war.

One check over a magistrate's power was collegiality (collega), which required that each magisterial office be held concurrently by at least two people. For example, two Consuls always served together. The check on the magistrate's power of Coercion was Provocatio, which was an early form of due process (habeas corpus

Habeas corpus

is a writ, or legal action, through which a prisoner can be released from unlawful detention. The remedy can be sought by the prisoner or by another person coming to his aid. Habeas corpus originated in the English legal system, but it is now available in many nations...

). Any Roman citizen had the absolute right to appeal any ruling by a magistrate to a Plebeian Tribune. In this case, the citizen would cry "provoco ad populum", which required the magistrate to wait for a Tribune to intervene, and make a ruling. Sometimes, the case was brought before the College of Tribunes, and sometimes before the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

(popular assembly). Since no Tribune could retain his powers outside of the city of Rome, the power of Coercion here was absolute. An additional check over a magistrate's power was that of Provincia, which required a division of responsibilities.

Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he had to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Since this did create problems for some magistrates (in particular, Consuls and Praetors), these magistrates occasionally had their imperium "prorogued" (prorogare

Prorogatio

In the constitution of ancient Rome, prorogatio was the extension of a commander's imperium beyond the one-year term of his magistracy, usually that of consul or praetor...

), which allowed them to retain the powers of the office as a Promagistrate

Promagistrate

A promagistrate is a person who acts in and with the authority and capacity of a magistrate, but without holding a magisterial office. A legal innovation of the Roman Republic, the promagistracy was invented in order to provide Rome with governors of overseas territories instead of having to elect...

. The result was that private citizens ended up with Consular and Praetorian imperium, without actually holding either office. Often, they used this power to act as provincial governors.

Ordinary Magistrates

The Consul of the Roman RepublicRoman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Two Consuls were elected for an annual term (from January through December) by the assembly of Roman soldiers, the Century Assembly

Century Assembly

The Century Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial...

. After they were elected, they were granted imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

powers by the assembly. If a Consul died before his term ended, another Consul (the consul suffectus), was elected to complete the original Consular term. Throughout the year, one Consul was superior in rank to the other Consul. This ranking flipped every month, between the two Consuls. Once a Consul's term ended, he held the honorary title of consulare for the rest of his time in the senate, and had to wait for ten years before standing for reelection to the Consulship. Consuls had supreme power in both civil and military matters, which was due, in part, to the fact that they held the highest ordinary grade of imperium (command) powers. While in the city of Rome, the Consul was the head of the Roman government. While components of public administration were delegated to other magistrates, the management of the government was under the ultimate authority of the Consul. The Consuls presided over the Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

and the Roman assemblies

Roman assemblies

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital...

, and had the ultimate responsibility to enforce policies and laws enacted by both institutions. The Consul was the chief diplomat, carried out business with foreign nations, and facilitated interactions between foreign ambassadors and the senate. Upon an order by the senate, the Consul was responsible for raising and commanding an army. While the Consuls had supreme military authority, they had to be provided with financial resources by the Roman Senate while they were commanding their armies. While abroad, the Consul had absolute power over his soldiers, and over any Roman province.

The Praetors administered civil law

Civil law (legal system)

Civil law is a legal system inspired by Roman law and whose primary feature is that laws are codified into collections, as compared to common law systems that gives great precedential weight to common law on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different...

and commanded provincial armies, and, eventually, began to act as chief judges over the courts. Praetors usually stood for election with the Consuls before the assembly of the soldiers, the Century Assembly. After they were elected, they were granted imperium powers by the assembly. In the absence of both senior and junior Consuls from the city, the Urban Praetor governed Rome, and presided over the Roman Senate and Roman assemblies

Roman assemblies

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new statutes, the carrying out of capital...

. Other Praetors had foreign affairs-related responsibilities, and often acted as governors of the provinces. Since Praetors held imperium powers, they could command an army.

Lictor

The lictor was a member of a special class of Roman civil servant, with special tasks of attending and guarding magistrates of the Roman Republic and Empire who held imperium, the right and power to command; essentially, a bodyguard...

s. In addition, they did not have the power to convene the Roman Senate or Roman assemblies. Technically they outranked all other ordinary magistrates (including Consuls and Praetors). This ranking, however, was solely a result of their prestige, rather than any real power they had. Since the office could be easily abused (as a result of its power over every ordinary citizen), only former Consuls (usually Patrician Consuls) were elected to the office. This is what gave the office its prestige. Their actions could not be vetoed by any magistrate other than a Plebeian Tribune, or a fellow Censor. No other ordinary magistrate could veto a Censor because no ordinary magistrate technically outranked a Censor. Tribunes, by virtue of their sacrosanctity as the representatives of the people, could veto anything or anyone. Censors usually did not have to act in unison, but if a Censor wanted to reduce the status of a citizen in a census, he had to act in unison with his colleague.

Censors could enroll citizens in the senate, or purge them from the senate. A Censor had the ability to fine a citizen, or to sell his property, which was often a punishment for either evading the census or having filed a fraudulent registration. Other actions that could result in a Censorial punishment were the poor cultivation of land

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

, cowardice or disobedience in the army, dereliction of civil duties, corruption, or debt. A Censor could reassign a citizen to a different Tribe

Tribal Assembly

The Tribal Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman citizens. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of thirty-five Tribes: Four Tribes encompassed citizens inside the city of Rome, while the other thirty-one Tribes encompassed...

(a civil unit of division), or place a punitive mark (nota) besides a man's name on the register. Later, a law (one of the Leges Clodiae

Leges Clodiae

Leges Clodiae were a series of laws passed by the Plebeian Council of the Roman Republic under the tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher in 58 BC. Clodius was a member of the patrician family Claudius; the alternate spelling of his name is sometimes regarded as a political gesture...

or "Clodian Laws") allowed a citizen to appeal a Censorial nota. Once a census was complete, a purification ceremony (the lustrum

Lustrum

A lustrum was a term for a five-year period in Ancient Rome.The lustration was originally a sacrifice for expiation and purification offered by one of the censors in the name of the Roman people at the close of the taking of the census...

) was performed by a Censor, which typically involved prayers for the upcoming five years. This was a religious ceremony that acted as the certification of the census, and was performed before the Century Assembly. Censors had several other duties as well, including the management of public contracts and the payment of individuals doing contract work for the state. Any act by the Censor that resulted in an expenditure of public money

Aerarium

Aerarium was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances....

required the approval of the senate.

Aedile

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

s were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, and often assisted the higher magistrates. The office was not on the cursus honorum

Cursus honorum

The cursus honorum was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in both the Roman Republic and the early Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The cursus honorum comprised a mixture of military and political administration posts. Each office had a minimum...

, and therefore did not mark the beginning of a political career. Every year, two Curule Aedile

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

s and two Plebeian Aediles were elected. The Tribal Assembly

Tribal Assembly

The Tribal Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman citizens. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of thirty-five Tribes: Four Tribes encompassed citizens inside the city of Rome, while the other thirty-one Tribes encompassed...

, while under the presidency of a higher magistrate (either a Consul or Praetor), elected the two Curule Aediles. While they had a curule chair, they did not have lictors, and thus they had no power of coercion. The Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

(principal popular assembly), under the presidency of a Plebeian Tribune

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

, elected the two Plebeian Aediles. Aediles had wide ranging powers over day-to-day affairs inside the city of Rome, and over the maintenance of public order. They had the power over public games and shows, and over the markets. They also had the power to repair and preserve temples, sewers and aqueducts, to maintain public records, and to issue edicts. Any expenditure of public funds, by either a Curule Aedile or a Plebeian Aedile, had to be authorized by the senate.

The office of Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

was considered to be the lowest ranking of all major political offices. Quaestors were elected by the Tribal Assembly, and the assignment of their responsibilities were settled by lot. Magistrates often chose which Quaestor accompanied them abroad, and these Quaestors often functioned as personal secretaries responsible for the allocation of money, including army pay. Urban Quaestors had several important responsibilities, such as the management of the public treasury, (the aerarium Saturni) where they monitored all items going into, and coming out of, the treasury. In addition, they often spoke publicly about the balances available in the treasury. The Quaestors could only issue public money for a particular purpose if they were authorized to do so by the senate. The Quaestors were assisted by scribe

Scribe

A scribe is a person who writes books or documents by hand as a profession and helps the city keep track of its records. The profession, previously found in all literate cultures in some form, lost most of its importance and status with the advent of printing...

s, who handled the actual accounting for the treasury. The treasury was a repository for documents, as well as for money. The texts of enacted statutes and decrees of the Roman Senate were deposited in the treasury under the supervision of the Quaestors.

Plebeian Magistrates

Since the Plebeian TribunesTribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

and Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

were elected by the Plebeians (commoners) in the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

, rather than by all of the People of Rome

SPQR

SPQR is an initialism from a Latin phrase, Senatus Populusque Romanus , referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic, and used as an official emblem of the modern day comune of Rome...

(Plebeians and the aristocratic Patrician class), they were technically not magistrates. While the term "Plebeian Magistrate" (magistratus plebeii) has been used as an approximation, it is technically a contradiction. The Plebeian Aedile functioned as the Tribune's assistant, and often performed similar duties as did the Curule Aediles (discussed above). In time, however, the differences between the Plebeian Aediles and the Curule Aediles disappeared.

Sacrosanct

Sacrosanctity was a right of tribunes in Ancient Rome not to be harmed physically. Plebeians took an oath to regard anyone who laid hands on a tribune as an outlaw liable to be killed without penalty...

. Their sacrosanctity was enforced by a pledge, taken by the Plebeians, to kill any person who harmed or interfered with a Tribune during his term of office. All of the powers of the Tribune derived from their sacrosanctity. One obvious consequence of this sacrosanctity was the fact that it was considered a capital offense to harm a Tribune, to disregard his veto, or to interfere with a Tribune. The sacrosanctity of a Tribune (and thus all of his legal powers) were only in effect so long as that Tribune was within the city of Rome. If the Tribune was abroad, the Plebeians in Rome could not enforce their oath to kill any individual who harmed or interfered with the Tribune. Since Tribunes were technically not magistrates, they had no magisterial powers ("major powers" or maior potestas), and thus could not rely on such powers to veto. Instead, they relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct. If a magistrate, an assembly or the senate did not comply with the orders of a Tribune, the Tribune could 'interpose the sacrosanctity of his person' (intercessio) to physically stop that particular action. Any resistance against the Tribune was tantamount to a violation of his sacrosanctity, and thus was considered a capital offense. Their lack of magisterial powers made them independent of all other magistrates, which also meant that no magistrate could veto a Tribune.

Tribunes could use their sacrosanctity to order the use of capital punishment against any person who interfered with their duties. Tribunes could also use their sacrosanctity as protection when physically manhandling an individual, such as when arrest

Arrest

An arrest is the act of depriving a person of his or her liberty usually in relation to the purported investigation and prevention of crime and presenting into the criminal justice system or harm to oneself or others...

ing someone. On a couple of rare occasions (such as during the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was a Roman Populares politician of the 2nd century BC and brother of Gaius Gracchus. As a plebeian tribune, his reforms of agrarian legislation caused political turmoil in the Republic. These reforms threatened the holdings of rich landowners in Italy...

), a Tribune might use a form of blanket obstruction, which could involve a broad veto over all governmental functions. While a Tribune could veto any act of the senate, the assemblies, or the magistrates, he could only veto the act, and not the actual measure. Therefore, he had to physically be present when the act was occurring. As soon as that Tribune was no longer present, the act could be completed as if there had never been a veto.

Tribunes, the only true representatives of the people, had the authority to enforce the right of Provocatio, which was a theoretical guarantee of due process, and a precursor to our own habeas corpus. If a magistrate was threatening to take action against a citizen, that citizen could yell "provoco ad populum", which would appeal the magistrate's decision to a Tribune. A Tribune had to assess the situation, and give the magistrate his approval before the magistrate could carry out the action. Sometimes the Tribune brought the case before the College of Tribunes or the Plebeian Council for a trial. Any action taken in spite of a valid provocatio was on its face illegal.

Extraordinary Magistrates

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

(magister populi or "Master of the Nation") was appointed for a six month term. The Dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate. While the Consul Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

and the contemporary historian Livy

Livy

Titus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

do mention the military uses of the dictatorship, others, such as the contemporary historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Caesar Augustus. His literary style was Attistic — imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.-Life:...

, mention its use for the purposes of maintaining order during times of Plebeian unrest. For a Dictator to be appointed, the Roman Senate had to pass a decree (a senatus consultum), authorizing a Roman Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

to nominate a Dictator, who then took office immediately. Often the Dictator resigned his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved. Ordinary magistrates (such as Consuls and Praetors) retained their offices, but lost their independence and became agents of the Dictator. If they disobeyed the Dictator, they could be forced out of office. While a Dictator could ignore the right of Provocatio, that right, as well as the Plebeian Tribune's independence, theoretically still existed during a Dictator's term. A Dictator's power was equivalent to that of the power of the two Consuls exercised conjointly, without any checks on their power by any other organ of government. Thus, Dictatorial appointments were tantamount to a six month restoration of the monarchy, with the Dictator taking the place of the old Roman King. This is why, for example, each Consul was accompanied by six lictors, whereas the Dictator (as the Roman King before him) was accompanied by twelve lictors.

Each Dictator appointed a Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse

The Master of the Horse was a position of varying importance in several European nations.-Magister Equitum :...

(magister equitum or Master of the Knights), to serve as his most senior lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

. The Master of the Horse had constitutional command authority (imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

) equivalent to a Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

, and often, when they authorized the appointment of a Dictator, the senate specified who was to be the Master of the Horse. In many respects, he functioned more as a parallel magistrate (like an inferior co-Consul) than he did as a direct subordinate. Whenever a Dictator's term ended, the term of his Master of the Horse ended as well. Often, the Dictator functioned principally as the master of the infantry (and thus the legions

Roman legion

A Roman legion normally indicates the basic ancient Roman army unit recruited specifically from Roman citizens. The organization of legions varied greatly over time but they were typically composed of perhaps 5,000 soldiers, divided into maniples and later into "cohorts"...

), while the Master of the Horse (as the name implies) functioned as the master of the cavalry. The Dictator, while not elected by the people, was technically a magistrate since he was nominated by an elected Consul. The Master of the Horse was also technically a magistrate, since he was nominated by the Dictator. Thus, both of these magistrates were referred to as "Extraordinary Magistrates".

The last ordinary Dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the senatus consultum ultimum

Senatus consultum ultimum

Senatus consultum ultimum , more properly senatus consultum de re publica defendenda is the modern term given to a decree of the Roman Senate during the late Roman Republic passed in times of emergency...

("ultimate decree of the senate") which suspended civil government, and declared something analogous to martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

. It declared "videant consules ne res publica detrimenti capiat" ("let the Consuls see to it that the state suffer no harm") which, in effect, vested the Consuls with dictatorial powers. There were several reasons for this change. Up until 202 BC, Dictators were often appointed to fight Plebeian unrest. In 217 BC, a law was passed that gave the popular assemblies the right to nominate Dictators. This, in effect, eliminated the monopoly that the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

had over this power. In addition, a series of laws were passed, which placed additional checks on the power of the Dictator.

See also

Further reading

- Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13.

- Cameron, A. The Later Roman Empire, (Fontana Press, 1993).

- Crawford, M. The Roman Republic, (Fontana Press, 1978).

- Gruen, E. S. "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974)

- Ihne, Wilhelm. Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering. 1853

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone. Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891

- Millar, F. The Emperor in the Roman World, (Duckworth, 1977, 1992).

- Mommsen, Theodor. Roman Constitutional Law. 1871–1888

- Tighe, Ambrose. The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co. 1886.

- Von Fritz, Kurt. The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975.

External links

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

- What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius

- Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, by Montesquieu