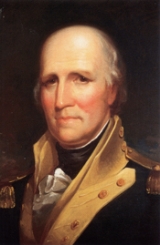

George Rogers Clark

Encyclopedia

George Rogers Clark was a soldier from Virginia

and the highest ranking American military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War

. He served as leader of the Kentucky

(then part of Virginia) militia

throughout much of the war. Clark is best known for his celebrated captures of Kaskaskia

(1778) and Vincennes

(1779), which greatly weakened British

influence in the Northwest Territory

. Because the British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

, Clark has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest."

Clark's military achievements all came before his 30th birthday. Afterwards he led militia in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War

, but was accused of being drunk on duty. Despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations, he was disgraced and forced to resign. He left Kentucky to live on the Indiana

frontier. Never fully reimbursed by Virginia for his wartime expenditures, Clark spent the final decades of his life evading creditors, and living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was involved in two failed conspiracies to open the Spanish

-controlled Mississippi River

to American traffic. After suffering a stroke and losing his leg, Clark was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

. Clark died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

, not far from the home of Thomas Jefferson

. He was the second of ten children of John Clark and Ann Rogers Clark, who were Anglicans

of English and Scots ancestry. Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son, William Clark, was too young to fight in the Revolution, but later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

. In about 1756, after the outbreak of the French and Indian War

(part of the worldwide Seven Years' War

), the family moved away from the frontier to Caroline County, Virginia

, and lived on a 400 acres (1.6 km²) plantation

that later grew to over 2000 acres (8.1 km²).

Little is known of Clark's schooling. He lived with his grandfather so he could attend Donald Robertson's school with James Madison

and John Taylor of Caroline

and received a common education. He was also tutored at home, as was usual for Virginian planters' children of the period. Becoming a planter, he was taught to survey land by his grandfather.

At age nineteen, Clark left his home on his first surveying trip into western Virginia. In 1772, as a twenty-year-old surveyor, Clark made his first trip into Kentucky via the Ohio River

at Pittsburgh. Thousands of settlers were entering the area as a result of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix

of 1768. In 1774, Clark was preparing to lead an expedition of ninety men down the Ohio River when war broke out with the American Indians

. Although most of Kentucky was not inhabited by Indians, several tribes used the area for hunting. The tribes living in the Ohio country

had not been party to the treaty signed with the Cherokee

, which ceded the Kentucky hunting grounds to Britain for settlement. They attacked the European-American settlers to try to push them out of the area, conflicts that eventually culminated in Lord Dunmore's War. Clark served in the war as a captain in the Virginia militia.

, settlers in Kentucky were involved in a dispute over the region's sovereignty. Richard Henderson, a judge and land speculator from North Carolina

, had purchased much of Kentucky from the Cherokee in an illegal treaty. Henderson intended to create a proprietary colony

known as Transylvania

, but many Kentucky settlers did not recognize Transylvania's authority over them. In June 1776, these settlers selected Clark and John Gabriel Jones

to deliver a petition to the Virginia General Assembly

, asking Virginia to formally extend its boundaries to include Kentucky. Clark and Jones traveled via the Wilderness Road

to Williamsburg

, where they convinced Governor Patrick Henry

to create Kentucky County, Virginia

. Clark was given 500 lb (226.8 kg) of gunpowder to help defend the settlements and was appointed a major

in the Kentucky County militia. Clark was just 24 years old, but older settlers such as Daniel Boone

, Benjamin Logan

, and Leonard Helm

looked to him as a leader.

, Native Americans waged war and raided the Kentucky settlers in hopes of reclaiming the region as their hunting ground. The Continental Army

could spare no men for an invasion of the Northwest or the defense of distant Kentucky, so its defense was left entirely to the local population. Clark participated in several skirmishes against the Native American raiders. As a leader of the defense of Kentucky, Clark believed that the best way to end these raids was to seize British outposts north of the Ohio River, thereby destroying British influence with the Indians. Clark asked Governor Henry for permission to lead a secret expedition to capture the nearest British posts, which were located in the Illinois country

. Governor Henry commissioned Clark as a lieutenant colonel

in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise troops for the expedition.

In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac

and marched to Kaskaskia

, taking it on the night of July 4. Cahokia

, Vincennes

, and several other villages and forts in British territory were subsequently captured without firing a shot, because most of the French-speaking and American Indian inhabitants were unwilling to take up arms on behalf of the British. To counter Clark's advance, Henry Hamilton reoccupied Vincennes with a small force. In February 1779, Clark returned to Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. The winter expedition was Clark's most significant military achievement and became the source of his reputation as an early American military hero. When news of his victory reached General George Washington

, Clark's success was celebrated and was used to encourage the alliance with France

. Washington recognized his achievement had been gained without support from the regular army in men or funds. Virginia capitalized on Clark's success by laying claim to the whole of the Old Northwest, calling it Illinois County.

Clark's ultimate goal during the Revolutionary War was to seize British-held Detroit, but he could never recruit enough men to make the attempt. The Kentucky militiamen generally preferred to defend their homes by staying closer to Kentucky rather than making a long and potentially perilous expedition to Detroit. In June 1780, a mixed force of British and Indians, including Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot and others, from Detroit invaded Kentucky

Clark's ultimate goal during the Revolutionary War was to seize British-held Detroit, but he could never recruit enough men to make the attempt. The Kentucky militiamen generally preferred to defend their homes by staying closer to Kentucky rather than making a long and potentially perilous expedition to Detroit. In June 1780, a mixed force of British and Indians, including Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot and others, from Detroit invaded Kentucky

with cannons, capturing two fortified settlements and carrying away hundreds of prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a retaliatory force that won a victory at the Shawnee village of Peckuwe, at what is now called George Rogers Clark Park near Springfield, Ohio

.

The next year Clark was promoted to brigadier general

by Governor Thomas Jefferson, and was given command of all the militia in the Kentucky and Illinois counties. He prepared again to lead an expedition against Detroit. Although Washington transferred a small group of regulars to assist Clark, the detachment was disastrously defeated

in August 1781 before they could meet up with Clark, ending the campaign.

In August 1782, another British-Indian force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks

. Although Clark had not been present at the battle, as senior military officer, he was severely criticized in the Virginia Council for the disaster. In response, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country, destroying several Indian towns

along the Great Miami River

in the last major expedition of the war.

The importance of Clark's activities in the Revolutionary War has been the subject of much debate among historians. As early as 1779 he was called the Conqueror of the Northwest by George Mason

. Because the British ceded the entire Old Northwest Territory

to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

, some historians, including William Hayden English

, credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original Thirteen Colonies

by seizing control of the Illinois country during the war. Clark's Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized. Other historians, such as Lowell Harrison, have downplayed the importance of the campaign in the peace negotiations and the outcome of the war, arguing that Clark's "conquest" was little more than a temporary occupation.

Clark was just thirty years old when the Revolutionary War ended, but his greatest military achievements were already behind him. Ever since Clark's victories in Illinois, settlers had been pouring into Kentucky, often illegally squatting on Indian land north of the Ohio River. From 1784 until 1788 Clark served as the superintendent-surveyor for Virginia's war veterans and surveyed the lands granted to them for their service in the war. The position brought a small income, but Clark devoted very little time to the enterprise. Clark helped to negotiate the Treaty of Fort McIntosh

Clark was just thirty years old when the Revolutionary War ended, but his greatest military achievements were already behind him. Ever since Clark's victories in Illinois, settlers had been pouring into Kentucky, often illegally squatting on Indian land north of the Ohio River. From 1784 until 1788 Clark served as the superintendent-surveyor for Virginia's war veterans and surveyed the lands granted to them for their service in the war. The position brought a small income, but Clark devoted very little time to the enterprise. Clark helped to negotiate the Treaty of Fort McIntosh

in 1785 and the Treaty of Fort Finney

in 1786 with tribes north of the river, but violence between Native Americans and Kentucky settlers continued to escalate.

According to a 1790 U.S. government report, 1,500 Kentucky settlers had been killed in Indian raids since the end of the Revolutionary War. In an attempt to end these raids, Clark led an expedition of 1,200 drafted men against Indian towns on the Wabash River

in 1786, one of the first actions of the Northwest Indian War

. The campaign ended without a victory: lacking supplies, about three hundred militiamen mutinied

, and Clark had to withdraw, but not before concluding a ceasefire with the Indians. It was rumored, most notably by James Wilkinson

, that Clark had often been drunk on duty. Many years later, Wilkinson was found to be working as a secret agent of the Spanish

government. When Clark learned of the rumors he demanded an official inquiry be made, but his request was declined by Governor of Virginia, and Virginia Council condemned Clark's actions. Clark's reputation was tarnished, he never again led men in battle, and he left Kentucky, moving into the Indiana

frontier near Clarksville

because record keeping on the frontier during the war had been haphazard. For his services in the war Virginia gave Clark a gift of 150000 acres (607 km²) of land. The soldiers who fought with Clark also received smaller tracts of land. Together with Clark's Grant

and his other holdings, his ownership encompassed all of present day Clark County, Indiana

and most of the surrounding counties. Although Clark had claims to tens of thousands of acres of land resulting from his military service and land speculation, he was "land-poor," meaning that he owned much land but lacked the means to make money from it.

With his career seemingly over and his prospects for prosperity doubtful, on February 2, 1793, Clark offered his services to Edmond-Charles Genêt

, the controversial ambassador of revolutionary France, hoping to earn money to maintain his estate. Western Americans were outraged that the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana

, denied Americans free access to the Mississippi River

, their only easy outlet for long distance commerce. The Washington Administration was also seemingly deaf to western concerns about opening the Mississippi to U.S. commerce. Clark proposed to Genêt that, with French financial support, he could lead an expedition to drive the Spanish out of the Mississippi Valley. Genêt appointed Clark "Major General in the Armies of France and Commander-in-chief of the French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi River." Clark began to organize a campaign to seize New Madrid

, St. Louis

, Natchez

, and New Orleans

, getting assistance from old comrades such as Benjamin Logan and John Montgomery

, and winning the tacit support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby

. Clark spent $4,680 ($ in 2009 chained dollars

) of his own money for supplies. In early 1794, however, President Washington issued a proclamation

forbidding Americans from violating U.S. neutrality and threatened to dispatch General Anthony Wayne

to Fort Massac

to stop the expedition. The French government recalled Genêt and revoked the commissions he granted to the Americans for the war against Spain. Clark's planned campaign gradually collapsed, and he was unable to convince the French to reimburse him for his expenses.

Due to his growing debt, it became impossible for Clark to continue holding his land, since it became subject to seizure. Much of his land he deeded to friends or transferred to family members where it could be held for him, so that it would not be lost to his creditors. After a few years, the lenders and their assigns closed in and deprived the veteran of almost all of the property that remained in his name. Clark, once the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small plot of land in Clarksville, where he built a small gristmill

which he worked with two African American

slaves. Clark lived on for another two decades, and continued to struggle with alcohol abuse

, a problem which had plagued him on-and-off for many years. He was very bitter about his treatment and neglect by Virginia, and blamed his misfortune on the state.

The Indiana Territory

chartered the Indiana Canal Company

in 1805 to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio, near Clarksville. Clark was named to the board of directors and was part of the surveying team that assisted in laying out the route of the canal. The company collapsed the next year before construction could begin, when two of the fellow board members, including Vice President

Aaron Burr

, were arrested for treason. Burr was plotting to seize Louisiana from Spain and open the Mississippi to the Americans. A large part of the company's $1.2 million($60.5 million in 2009 chained dollars) in investments was unaccounted for, and where the funds went was never determined.

In 1809, Clark suffered a severe stroke

In 1809, Clark suffered a severe stroke

. Falling into an operating fireplace, he suffered a burn on one leg so severe as to necessitate the amputation of the limb. It was impossible for Clark to continue to operate his mill, so he became a dependent member of the household of his brother-in-law, Major William Croghan, a planter at Locust Grove

farm eight miles (13 km) from the growing town of Louisville. During 1812, the Virginia General Assembly granted Clark a pension of four hundred dollars per year, and finally recognized his services in the Revolution by granting him a ceremonial sword

. After a second stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove, February 13, 1818, and was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later.

In his funeral oration, Judge John Rowan succinctly summed up the stature and importance of George Rogers Clark during the critical years on the Trans-Appalachian frontier: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around."

Clark's body was exhumed along with the rest of his family members on October 29, 1869, and reburied at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

Several years after Clark's death the state of Virginia granted his estate $30,000 ($ in 2009 chained dollars) as a partial payment on the debts that they owed him. The government of Virginia continued to find debt to Clark for decades, with the last payment to his estate being made in 1913. Clark never married and he kept no account of any romantic relationships, although his family held that he had once been in love with Teresa de Leyba, sister of Don Fernando de Leyba

, the Lieutenant Governor of Spanish Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin in the Draper Manuscripts attest to their belief in Clark's lifelong disappointment over the failed romance.

Calvin Coolidge

ordered a memorial to George Rogers Clark to be erected in Vincennes. Completed in 1933, the George Rogers Clark Memorial, built in Roman Classical

style, stands on what was then believed to be the site of Fort Sackville, and is now the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park

. It includes a statue of Clark by Hermon Atkins MacNeil

. On February 25, 1929, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the surrender of Fort Sackville, the U.S. Post Office Department

issued a 2-cent postage stamp

that depicted the surrender. In April 1929, the Paul Revere

Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

of Muncie, Indiana

erected a monument to George Rogers Clark on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, Virginia

. The marker doesn't identify the connection between General Clark and Fredericksburg, so this choice of location is currently a mystery. In 1975, the Indiana General Assembly

designated February 25 George Rogers Clark Day in Indiana. Built in 1929, the George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge (Second Street Bridge) carries U.S. Highway 31, over the Ohio River

at Louisville, Kentucky

.

Other statues of Clark can be found in:

Places named for Clark include counties in Illinois, Indiana

, Kentucky

(home to George Rogers Clark High School), Ohio

(home to Clark State Community College

), and Virginia

, and communities in West Virginia (Clarksburg

), Indiana (Clarksville

), and Tennessee (also Clarksville

). Clark Street

in Chicago, Illinois is named for him, as is a campsite in the Woodland Trails Scout Reservation

, Camden, Ohio

.

Schools named after Clark include:

Schools named after Clark include:

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and the highest ranking American military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. He served as leader of the Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

(then part of Virginia) militia

Militia (United States)

The role of militia, also known as military service and duty, in the United States is complex and has transformed over time.Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control, Page 36. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995. " The term militia can be used to describe any number of groups within the...

throughout much of the war. Clark is best known for his celebrated captures of Kaskaskia

Kaskaskia, Illinois

Kaskaskia is a village in Randolph County, Illinois, United States. In the 2010 census the population was 14, making it the second-smallest incorporated community in the State of Illinois in terms of population. A major French colonial town of the Illinois Country, its peak population was about...

(1778) and Vincennes

Vincennes, Indiana

Vincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the Wabash River in the southwestern part of the state. The population was 18,701 at the 2000 census...

(1779), which greatly weakened British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

influence in the Northwest Territory

Northwest Territory

The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio...

. Because the British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

, Clark has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest."

Clark's military achievements all came before his 30th birthday. Afterwards he led militia in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War

Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War , also known as Little Turtle's War and by various other names, was a war fought between the United States and a confederation of numerous American Indian tribes for control of the Northwest Territory...

, but was accused of being drunk on duty. Despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations, he was disgraced and forced to resign. He left Kentucky to live on the Indiana

Indiana Territory

The Territory of Indiana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, until November 7, 1816, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana....

frontier. Never fully reimbursed by Virginia for his wartime expenditures, Clark spent the final decades of his life evading creditors, and living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was involved in two failed conspiracies to open the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

-controlled Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

to American traffic. After suffering a stroke and losing his leg, Clark was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

. Clark died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

Early years

George Rogers Clark was born on November 19, 1752 in Charlottesville, VirginiaCharlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville is an independent city geographically surrounded by but separate from Albemarle County in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States, and named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of King George III of the United Kingdom.The official population estimate for...

, not far from the home of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

. He was the second of ten children of John Clark and Ann Rogers Clark, who were Anglicans

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

of English and Scots ancestry. Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son, William Clark, was too young to fight in the Revolution, but later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

. In about 1756, after the outbreak of the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

(part of the worldwide Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

), the family moved away from the frontier to Caroline County, Virginia

Caroline County, Virginia

Caroline County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 28,545. Its county seat is Bowling Green. Caroline County is also home to The Meadow stables, the birthplace of the renowned racehorse Secretariat, winner of the 1973 Kentucky Derby, Preakness and...

, and lived on a 400 acres (1.6 km²) plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

that later grew to over 2000 acres (8.1 km²).

Little is known of Clark's schooling. He lived with his grandfather so he could attend Donald Robertson's school with James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

and John Taylor of Caroline

John Taylor of Caroline

John Taylor usually called John Taylor of Caroline was a politician and writer. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and in the United States Senate . He wrote several books on politics and agriculture...

and received a common education. He was also tutored at home, as was usual for Virginian planters' children of the period. Becoming a planter, he was taught to survey land by his grandfather.

At age nineteen, Clark left his home on his first surveying trip into western Virginia. In 1772, as a twenty-year-old surveyor, Clark made his first trip into Kentucky via the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

at Pittsburgh. Thousands of settlers were entering the area as a result of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was an important treaty between North American Indians and the British Empire. It was signed in 1768 at Fort Stanwix, located in present-day Rome, New York...

of 1768. In 1774, Clark was preparing to lead an expedition of ninety men down the Ohio River when war broke out with the American Indians

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

. Although most of Kentucky was not inhabited by Indians, several tribes used the area for hunting. The tribes living in the Ohio country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

had not been party to the treaty signed with the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

, which ceded the Kentucky hunting grounds to Britain for settlement. They attacked the European-American settlers to try to push them out of the area, conflicts that eventually culminated in Lord Dunmore's War. Clark served in the war as a captain in the Virginia militia.

Revolutionary War

As the American Revolutionary War began in the EastEastern United States

The Eastern United States, the American East, or simply the East is traditionally defined as the states east of the Mississippi River. The first two tiers of states west of the Mississippi have traditionally been considered part of the West, but can be included in the East today; usually in...

, settlers in Kentucky were involved in a dispute over the region's sovereignty. Richard Henderson, a judge and land speculator from North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, had purchased much of Kentucky from the Cherokee in an illegal treaty. Henderson intended to create a proprietary colony

Proprietary colony

A proprietary colony was a colony in which one or more individuals, usually land owners, remaining subject to their parent state's sanctions, retained rights that are today regarded as the privilege of the state, and in all cases eventually became so....

known as Transylvania

Transylvania (colony)

Transylvania, or the Transylvania Colony, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in 1775 by Richard Henderson, who controlled the North Carolina based Transylvania Company, which had reached an agreement to purchase the land from the Cherokee in the "Treaty of Sycamore Shoals"...

, but many Kentucky settlers did not recognize Transylvania's authority over them. In June 1776, these settlers selected Clark and John Gabriel Jones

John Gabriel Jones

John Gabriel Jones was a colonial American pioneer and politician. An early settler of Kentucky, he and George Rogers Clark sought to petition Virginia to allow Kentucky to become a part of the Colony of Virginia at the outset of the American Revolution.He was named in honor of his uncle, the...

to deliver a petition to the Virginia General Assembly

Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere, established on July 30, 1619. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of a lower house, the Virginia House of Delegates, with 100 members,...

, asking Virginia to formally extend its boundaries to include Kentucky. Clark and Jones traveled via the Wilderness Road

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was the principal route used by settlers for more than fifty years to reach Kentucky from the East. In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail for the Transylvania Company from Fort Chiswell in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky. It was later lengthened,...

to Williamsburg

Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city located on the Virginia Peninsula in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia, USA. As of the 2010 Census, the city had an estimated population of 14,068. It is bordered by James City County and York County, and is an independent city...

, where they convinced Governor Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry was an orator and politician who led the movement for independence in Virginia in the 1770s. A Founding Father, he served as the first and sixth post-colonial Governor of Virginia from 1776 to 1779 and subsequently, from 1784 to 1786...

to create Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County, Virginia

Kentucky County was formed by the Commonwealth of Virginia by dividing Fincastle County into three new counties: Kentucky, Washington, and Montgomery, effective December 31, 1776. Four years later Kentucky County was abolished on June 30, 1780, when it was divided into Fayette, Jefferson, and...

. Clark was given 500 lb (226.8 kg) of gunpowder to help defend the settlements and was appointed a major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

in the Kentucky County militia. Clark was just 24 years old, but older settlers such as Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, explorer, and frontiersman whose frontier exploits mad']'e him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. Boone is most famous for his exploration and settlement of what is now the Commonwealth of Kentucky, which was then beyond the western borders of...

, Benjamin Logan

Benjamin Logan

Benjamin Logan was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Shelby County, Kentucky. As colonel of the Kentucky County militia of Virginia during the American Revolutionary War, he was second-in-command of militia in Kentucky. Logan was a leader in Kentucky's efforts to become a state...

, and Leonard Helm

Leonard Helm

Leonard Helm was an early pioneer of Kentucky, and a Virginia officer during the American Revolutionary War. Born around 1720 probably in Fauquier County, Virginia, he died in poverty while fighting Native American allies of British troops during one of the last engagements of the Revolutionary...

looked to him as a leader.

Illinois campaign

In 1777, the American Revolutionary War intensified in Kentucky. Armed and encouraged by British lieutenant governor Henry Hamilton at Fort DetroitFort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Détroit was a fort established by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701. The location of the former fort is now in the city of Detroit in the U.S...

, Native Americans waged war and raided the Kentucky settlers in hopes of reclaiming the region as their hunting ground. The Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

could spare no men for an invasion of the Northwest or the defense of distant Kentucky, so its defense was left entirely to the local population. Clark participated in several skirmishes against the Native American raiders. As a leader of the defense of Kentucky, Clark believed that the best way to end these raids was to seize British outposts north of the Ohio River, thereby destroying British influence with the Indians. Clark asked Governor Henry for permission to lead a secret expedition to capture the nearest British posts, which were located in the Illinois country

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

. Governor Henry commissioned Clark as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, a lieutenant colonel is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of major and just below the rank of colonel. It is equivalent to the naval rank of commander in the other uniformed services.The pay...

in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise troops for the expedition.

In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac

Fort Massac

Fort Massac is a colonial and early National-era fort on the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, United States.Legend has it that, as early as 1540, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his soldiers constructed a primitive fortification here to defend themselves from native attack...

and marched to Kaskaskia

Kaskaskia, Illinois

Kaskaskia is a village in Randolph County, Illinois, United States. In the 2010 census the population was 14, making it the second-smallest incorporated community in the State of Illinois in terms of population. A major French colonial town of the Illinois Country, its peak population was about...

, taking it on the night of July 4. Cahokia

Cahokia, Illinois

Cahokia is a village in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2000 census, the village had a population of 16,391. The name is a reference to one of the clans of the historic Illini confederacy, who were encountered by early French explorers to the region.Early European settlers also...

, Vincennes

Vincennes, Indiana

Vincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the Wabash River in the southwestern part of the state. The population was 18,701 at the 2000 census...

, and several other villages and forts in British territory were subsequently captured without firing a shot, because most of the French-speaking and American Indian inhabitants were unwilling to take up arms on behalf of the British. To counter Clark's advance, Henry Hamilton reoccupied Vincennes with a small force. In February 1779, Clark returned to Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. The winter expedition was Clark's most significant military achievement and became the source of his reputation as an early American military hero. When news of his victory reached General George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, Clark's success was celebrated and was used to encourage the alliance with France

Franco-American alliance

The Franco-American alliance refers to the 1778 alliance between Louis XVI's France and the United States, during the American Revolutionary War. Formalized in the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, it was a military pact in which France provided arms and money, and engaged in full-scale war with Britain. ...

. Washington recognized his achievement had been gained without support from the regular army in men or funds. Virginia capitalized on Clark's success by laying claim to the whole of the Old Northwest, calling it Illinois County.

Final years of the war

Bird's invasion of Kentucky

Bird's invasion of Kentucky during the American Revolutionary War was one phase of an extensive planned series of operations planned by the British in 1780, whereby the entire West, from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico, was to be swept clear of both Spanish and colonial resistance.While Bird's...

with cannons, capturing two fortified settlements and carrying away hundreds of prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a retaliatory force that won a victory at the Shawnee village of Peckuwe, at what is now called George Rogers Clark Park near Springfield, Ohio

Springfield, Ohio

Springfield is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Clark County. The municipality is located in southwestern Ohio and is situated on the Mad River, Buck Creek and Beaver Creek, approximately west of Columbus and northeast of Dayton. Springfield is home to Wittenberg...

.

The next year Clark was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

by Governor Thomas Jefferson, and was given command of all the militia in the Kentucky and Illinois counties. He prepared again to lead an expedition against Detroit. Although Washington transferred a small group of regulars to assist Clark, the detachment was disastrously defeated

Lochry's Defeat

Lochry's Defeat, also known as the Lochry massacre, was a battle fought on August 24, 1781, near present-day Aurora, Indiana, in the United States...

in August 1781 before they could meet up with Clark, ending the campaign.

In August 1782, another British-Indian force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks

Battle of Blue Licks

The Battle of Blue Licks, fought on August 19, 1782, was one of the last battles of the American Revolutionary War. The battle occurred ten months after Lord Cornwallis's famous surrender at Yorktown, which had effectively ended the war in the east...

. Although Clark had not been present at the battle, as senior military officer, he was severely criticized in the Virginia Council for the disaster. In response, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country, destroying several Indian towns

Battle of Piqua

The Battle of Piqua, also known as the Battle of Pekowee or Pekowi, was part of the western campaign during the American Revolutionary War...

along the Great Miami River

Great Miami River

The Great Miami River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately long, in southwestern Ohio in the United States...

in the last major expedition of the war.

The importance of Clark's activities in the Revolutionary War has been the subject of much debate among historians. As early as 1779 he was called the Conqueror of the Northwest by George Mason

George Mason

George Mason IV was an American Patriot, statesman and a delegate from Virginia to the U.S. Constitutional Convention...

. Because the British ceded the entire Old Northwest Territory

Northwest Territory

The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio...

to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

, some historians, including William Hayden English

William Hayden English

William Hayden English was an American politician from Indiana.William English was most famous for his role in the passage of the infamous, pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution of Kansas in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1858...

, credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original Thirteen Colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

by seizing control of the Illinois country during the war. Clark's Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized. Other historians, such as Lowell Harrison, have downplayed the importance of the campaign in the peace negotiations and the outcome of the war, arguing that Clark's "conquest" was little more than a temporary occupation.

Later years

Treaty of Fort McIntosh

The Treaty of Fort McIntosh was a treaty between the United States government and representatives of the Wyandotte, Delaware, Chippewa and Ottawa nations of Native Americans...

in 1785 and the Treaty of Fort Finney

Treaty of Fort Finney

The Treaty of Fort Finney, also known as the Treaty at the Mouth of the Great Miami, was signed in 1786 between the United States and Shawnee leaders after the American Revolutionary War, ceding parts of the Ohio country to the United States. The treaty was reluctantly signed by the Shawnees, and...

in 1786 with tribes north of the river, but violence between Native Americans and Kentucky settlers continued to escalate.

According to a 1790 U.S. government report, 1,500 Kentucky settlers had been killed in Indian raids since the end of the Revolutionary War. In an attempt to end these raids, Clark led an expedition of 1,200 drafted men against Indian towns on the Wabash River

Wabash River

The Wabash River is a river in the Midwestern United States that flows southwest from northwest Ohio near Fort Recovery across northern Indiana to southern Illinois, where it forms the Illinois-Indiana border before draining into the Ohio River, of which it is the largest northern tributary...

in 1786, one of the first actions of the Northwest Indian War

Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War , also known as Little Turtle's War and by various other names, was a war fought between the United States and a confederation of numerous American Indian tribes for control of the Northwest Territory...

. The campaign ended without a victory: lacking supplies, about three hundred militiamen mutinied

Mutiny

Mutiny is a conspiracy among members of a group of similarly situated individuals to openly oppose, change or overthrow an authority to which they are subject...

, and Clark had to withdraw, but not before concluding a ceasefire with the Indians. It was rumored, most notably by James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson was an American soldier and statesman, who was associated with several scandals and controversies. He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, but was twice compelled to resign...

, that Clark had often been drunk on duty. Many years later, Wilkinson was found to be working as a secret agent of the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

government. When Clark learned of the rumors he demanded an official inquiry be made, but his request was declined by Governor of Virginia, and Virginia Council condemned Clark's actions. Clark's reputation was tarnished, he never again led men in battle, and he left Kentucky, moving into the Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

frontier near Clarksville

Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River as a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 21,724 at the 2010 census. The town, once a home site to George Rogers Clark, was founded in 1783 and is the oldest American town in the Northwest...

Life in Indiana

Clark lived most of the rest of his life in financial difficulties. Clark had financed the majority of his military campaigns with borrowed funds. When creditors began to come to him for these unpaid debts, he was unable to obtain recompense from Virginia or the United States CongressUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

because record keeping on the frontier during the war had been haphazard. For his services in the war Virginia gave Clark a gift of 150000 acres (607 km²) of land. The soldiers who fought with Clark also received smaller tracts of land. Together with Clark's Grant

Clark's Grant

Clark's Grant was a tract of land granted to George Rogers Clark and the soldiers who fought with him during the American Revolutionary War by the state of Virginia in honor of their service...

and his other holdings, his ownership encompassed all of present day Clark County, Indiana

Clark County, Indiana

Clark County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana, located directly across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. At the 2010 Census, the population was 110,232. The county seat is Jeffersonville. Clarksville is also a major city in the county...

and most of the surrounding counties. Although Clark had claims to tens of thousands of acres of land resulting from his military service and land speculation, he was "land-poor," meaning that he owned much land but lacked the means to make money from it.

With his career seemingly over and his prospects for prosperity doubtful, on February 2, 1793, Clark offered his services to Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt , also known as Citizen Genêt, was a French ambassador to the United States during the French Revolution.-Early life:Genêt was born in Versailles in 1763...

, the controversial ambassador of revolutionary France, hoping to earn money to maintain his estate. Western Americans were outraged that the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana

Louisiana (New Spain)

Louisiana was the name of an administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1764 to 1803 that represented territory west of the Mississippi River basin, plus New Orleans...

, denied Americans free access to the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

, their only easy outlet for long distance commerce. The Washington Administration was also seemingly deaf to western concerns about opening the Mississippi to U.S. commerce. Clark proposed to Genêt that, with French financial support, he could lead an expedition to drive the Spanish out of the Mississippi Valley. Genêt appointed Clark "Major General in the Armies of France and Commander-in-chief of the French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi River." Clark began to organize a campaign to seize New Madrid

New Madrid, Missouri

New Madrid is a city in New Madrid County, Missouri, 42 miles south by west of Cairo, Illinois, on the Mississippi River. New Madrid was founded in 1788 by American frontiersmen. In 1900, 1,489 people lived in New Madrid, Missouri; in 1910, the population was 1,882. The population was 3,334 at...

, St. Louis

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

, Natchez

Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez is the county seat of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. With a total population of 18,464 , it is the largest community and the only incorporated municipality within Adams County...

, and New Orleans

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

, getting assistance from old comrades such as Benjamin Logan and John Montgomery

John Montgomery (pioneer)

Colonel John Montgomery was an early American soldier, settler, and explorer. He is credited with founding the city of Clarksville, Tennessee, and the county of Montgomery County, Tennessee is named for him....

, and winning the tacit support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby was the first and fifth Governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina. He was also a soldier in Lord Dunmore's War, the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812...

. Clark spent $4,680 ($ in 2009 chained dollars

Chained dollars

Chained dollars is a method of adjusting real dollar amounts for inflation over time, so as to allow comparison of figures from different years. The U.S. Department of Commerce introduced the chained-dollar measure in 1996...

) of his own money for supplies. In early 1794, however, President Washington issued a proclamation

Proclamation of Neutrality

The Proclamation of Neutrality was a formal announcement issued by United States President George Washington on April 22, 1793, declaring the nation neutral in the conflict between France and Great Britain. It threatened legal proceedings against any American providing assistance to any country at...

forbidding Americans from violating U.S. neutrality and threatened to dispatch General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne was a United States Army general and statesman. Wayne adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his military exploits and fiery personality quickly earned him a promotion to the rank of brigadier general and the sobriquet of Mad Anthony.-Early...

to Fort Massac

Fort Massac

Fort Massac is a colonial and early National-era fort on the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, United States.Legend has it that, as early as 1540, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his soldiers constructed a primitive fortification here to defend themselves from native attack...

to stop the expedition. The French government recalled Genêt and revoked the commissions he granted to the Americans for the war against Spain. Clark's planned campaign gradually collapsed, and he was unable to convince the French to reimburse him for his expenses.

Due to his growing debt, it became impossible for Clark to continue holding his land, since it became subject to seizure. Much of his land he deeded to friends or transferred to family members where it could be held for him, so that it would not be lost to his creditors. After a few years, the lenders and their assigns closed in and deprived the veteran of almost all of the property that remained in his name. Clark, once the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small plot of land in Clarksville, where he built a small gristmill

Gristmill

The terms gristmill or grist mill can refer either to a building in which grain is ground into flour, or to the grinding mechanism itself.- Early history :...

which he worked with two African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

slaves. Clark lived on for another two decades, and continued to struggle with alcohol abuse

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is a broad term for problems with alcohol, and is generally used to mean compulsive and uncontrolled consumption of alcoholic beverages, usually to the detriment of the drinker's health, personal relationships, and social standing...

, a problem which had plagued him on-and-off for many years. He was very bitter about his treatment and neglect by Virginia, and blamed his misfortune on the state.

The Indiana Territory

Indiana Territory

The Territory of Indiana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, until November 7, 1816, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana....

chartered the Indiana Canal Company

Indiana Canal Company

The Indiana Canal Company was a corporation first established in 1805 for the purpose of building a canal around the Falls of the Ohio on the Indiana side of the Ohio River...

in 1805 to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio, near Clarksville. Clark was named to the board of directors and was part of the surveying team that assisted in laying out the route of the canal. The company collapsed the next year before construction could begin, when two of the fellow board members, including Vice President

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr, Jr. was an important political figure in the early history of the United States of America. After serving as a Continental Army officer in the Revolutionary War, Burr became a successful lawyer and politician...

, were arrested for treason. Burr was plotting to seize Louisiana from Spain and open the Mississippi to the Americans. A large part of the company's $1.2 million($60.5 million in 2009 chained dollars) in investments was unaccounted for, and where the funds went was never determined.

Return to Kentucky

Stroke

A stroke, previously known medically as a cerebrovascular accident , is the rapidly developing loss of brain function due to disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This can be due to ischemia caused by blockage , or a hemorrhage...

. Falling into an operating fireplace, he suffered a burn on one leg so severe as to necessitate the amputation of the limb. It was impossible for Clark to continue to operate his mill, so he became a dependent member of the household of his brother-in-law, Major William Croghan, a planter at Locust Grove

Historic Locust Grove

Historic Locust Grove is a 55-acre 18th century farm site and National Historic Landmark situated in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky . The site is presently owned by the Louisville Metro government, and operated as a historic interpretive site by Historic Locust Grove, Inc.The main feature on...

farm eight miles (13 km) from the growing town of Louisville. During 1812, the Virginia General Assembly granted Clark a pension of four hundred dollars per year, and finally recognized his services in the Revolution by granting him a ceremonial sword

Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration...

. After a second stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove, February 13, 1818, and was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later.

In his funeral oration, Judge John Rowan succinctly summed up the stature and importance of George Rogers Clark during the critical years on the Trans-Appalachian frontier: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around."

Clark's body was exhumed along with the rest of his family members on October 29, 1869, and reburied at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

Several years after Clark's death the state of Virginia granted his estate $30,000 ($ in 2009 chained dollars) as a partial payment on the debts that they owed him. The government of Virginia continued to find debt to Clark for decades, with the last payment to his estate being made in 1913. Clark never married and he kept no account of any romantic relationships, although his family held that he had once been in love with Teresa de Leyba, sister of Don Fernando de Leyba

Fernando de Leyba

Don Fernando de Leyba was a Spanish officer and politician who served as the third governor of Upper Louisiana from 1778 until his death.Little is known of De Leyba's life until his appointment to the position of governor on June 14, 1778...

, the Lieutenant Governor of Spanish Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin in the Draper Manuscripts attest to their belief in Clark's lifelong disappointment over the failed romance.

Legacy

On May 23, 1928, PresidentPresident of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

ordered a memorial to George Rogers Clark to be erected in Vincennes. Completed in 1933, the George Rogers Clark Memorial, built in Roman Classical

Classical architecture

Classical architecture is a mode of architecture employing vocabulary derived in part from the Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, enriched by classicizing architectural practice in Europe since the Renaissance...

style, stands on what was then believed to be the site of Fort Sackville, and is now the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park

George Rogers Clark National Historical Park

George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, located in Vincennes on the banks of the Wabash River at what is believed to be the site of Fort Sackville, is a United States National Historical Park. A classical memorial here was authorized under President Calvin Coolidge and dedicated by President...

. It includes a statue of Clark by Hermon Atkins MacNeil

Hermon Atkins MacNeil

Hermon Atkins MacNeil was an American sculptor born in Chelsea, Massachusetts.He was an instructor in industrial art at Cornell University from 1886 to 1889, and was then a pupil of Henri M. Chapu and Alexandre Falguière in Paris...

. On February 25, 1929, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the surrender of Fort Sackville, the U.S. Post Office Department

United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service is an independent agency of the United States government responsible for providing postal service in the United States...

issued a 2-cent postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

that depicted the surrender. In April 1929, the Paul Revere

Paul Revere

Paul Revere was an American silversmith and a patriot in the American Revolution. He is most famous for alerting Colonial militia of approaching British forces before the battles of Lexington and Concord, as dramatized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem, Paul Revere's Ride...

Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution is a lineage-based membership organization for women who are descended from a person involved in United States' independence....

of Muncie, Indiana

Muncie, Indiana

Muncie is a city in Center Township, Delaware County in east central Indiana, best known as the home of Ball State University and the birthplace of the Ball Corporation. It is the principal city of the Muncie, Indiana, Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a population of 118,769...

erected a monument to George Rogers Clark on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia located south of Washington, D.C., and north of Richmond. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 24,286...

. The marker doesn't identify the connection between General Clark and Fredericksburg, so this choice of location is currently a mystery. In 1975, the Indiana General Assembly

Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate...

designated February 25 George Rogers Clark Day in Indiana. Built in 1929, the George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge (Second Street Bridge) carries U.S. Highway 31, over the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

at Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

.

Other statues of Clark can be found in:

- Metropolis, Fort Massac, Illinois, by sculptor Leon HermantLeon HermantLeon Hermant was a French-American sculptor best known for his architectural sculpture.Hermant was born in France, educated in Europe and came to America in 1904 to work on the French Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri...

, placed by the Daughters of the American RevolutionDaughters of the American RevolutionThe Daughters of the American Revolution is a lineage-based membership organization for women who are descended from a person involved in United States' independence....

in the early 1900s. - Louisville, Kentucky, by sculptor Felix de WeldonFelix de WeldonFelix Weihs de Weldon was an American sculptor. His most famous piece is the Marine Corps War Memorial of five U.S. Marines and one sailor raising the flag of the United States on Iwo Jima during World War Two.-Biography:...

, at Riverfront Plaza/BelvedereRiverfront Plaza/BelvedereRiverfront Plaza/Belvedere is a public area on the Ohio River in Downtown Louisville, Kentucky, USA. Although proposed as early as 1930, the project did not get off the ground until $13.5 million in funding was secured in 1969 to revitalize the downtown area . On April 27, 1973 the Riverfront...

, next to the wharf on the Ohio River. - Springfield, OhioSpringfield, OhioSpringfield is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Clark County. The municipality is located in southwestern Ohio and is situated on the Mad River, Buck Creek and Beaver Creek, approximately west of Columbus and northeast of Dayton. Springfield is home to Wittenberg...

, by Charles KeckCharles KeckCharles Keck was an American sculptor, born in New York City. He studied in the National Academy of Design and Art Students League with Philip Martiny and was an assistant to Augustus Saint-Gaudens from 1893 to 1898. He also attended the American Academy in Rome. He is best known for his...

at the site of the Battle of PiquaBattle of PiquaThe Battle of Piqua, also known as the Battle of Pekowee or Pekowi, was part of the western campaign during the American Revolutionary War...

. - Charlottesville, VirginiaCharlottesville, VirginiaCharlottesville is an independent city geographically surrounded by but separate from Albemarle County in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States, and named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of King George III of the United Kingdom.The official population estimate for...

, by Robert Aitken on the grounds of the University of VirginiaUniversity of VirginiaThe University of Virginia is a public research university located in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, founded by Thomas Jefferson...

. - Quincy, IllinoisQuincy, IllinoisQuincy, known as Illinois' "Gem City," is a river city along the Mississippi River and the county seat of Adams County. As of the 2010 census the city held a population of 40,633. The city anchors its own micropolitan area and is the economic and regional hub of West-central Illinois, catering a...

, in Riverview Park, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. - Indianapolis, IndianaIndianapolis, IndianaIndianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

, by sculptor John H. Mahoney, on Monument Circle

Places named for Clark include counties in Illinois, Indiana

Clark County, Indiana

Clark County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana, located directly across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. At the 2010 Census, the population was 110,232. The county seat is Jeffersonville. Clarksville is also a major city in the county...

, Kentucky

Clark County, Kentucky

Clark County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It was formed in 1793. The population was 35,613 in the 2010 Census. Its county seat is Winchester, Kentucky...

(home to George Rogers Clark High School), Ohio

Clark County, Ohio

As of the census of 2000, there were 144,742 people, 56,648 households, and 39,370 families residing in the county. The population density was 362 people per square mile . There were 61,056 housing units at an average density of 153 per square mile...

(home to Clark State Community College

Clark State Community College

Clark State Community College began in 1962 as the Springfield and Clark County Technical Education Program in an effort to meet the post-secondary, technical education needs of Springfield and the surrounding area. In 1966 the name was changed to Clark County Technical Institute and was chartered...

), and Virginia

Clarke County, Virginia

Clarke County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the population was 14,034. Its county seat is Berryville.-History:Clarke County was established in 1836 by Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron who built a home, Greenway Court, on part of his 5 million acre property,...

, and communities in West Virginia (Clarksburg

Clarksburg, West Virginia

Clarksburg is a city in and the county seat of Harrison County, West Virginia, United States, in the north-central region of the state. It is the principal city of the Clarksburg, WV Micropolitan Statistical Area...

), Indiana (Clarksville

Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River as a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 21,724 at the 2010 census. The town, once a home site to George Rogers Clark, was founded in 1783 and is the oldest American town in the Northwest...

), and Tennessee (also Clarksville

Clarksville, Tennessee

Clarksville is a city in and the county seat of Montgomery County, Tennessee, United States, and the fifth largest city in the state. The population was 132,929 in 2010 United States Census...

). Clark Street

Clark Street (Chicago)

Clark Street is a north-south street in Chicago, Illinois that runs close to the shore of Lake Michigan from the northern city boundary with Evanston, to 2200 South in the city street numbering system...

in Chicago, Illinois is named for him, as is a campsite in the Woodland Trails Scout Reservation

Woodland Trails Scout Reservation

Woodland Trails Scout Reservation is a camping facility owned and operated by the Miami Valley Council, Boy Scouts of America in Camden, Ohio, USA.- History :...

, Camden, Ohio

Camden, Ohio

Camden is a village in Preble County, Ohio, United States. The population was 2,302 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Dayton Metropolitan Statistical Area...

.

- George Rogers Clark College in Indianapolis, Indiana (closed 1992)

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School in Clarksville, Indiana (closed 2010)

- George Rogers Clark Middle/High School in Hammond, IndianaHammond, IndianaHammond is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. It is part of the Chicago metropolitan area. The population was 80,830 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Hammond is located at ....

, - George Rogers Clark High School in Winchester, KentuckyWinchester, KentuckyWinchester is a city in and the county seat of Clark County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,724 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Lexington-Fayette, KY Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

- Clark Middle School in Winchester, KentuckyWinchester, KentuckyWinchester is a city in and the county seat of Clark County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,724 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Lexington-Fayette, KY Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

- Clark Elementary School in Charlottesville, VirginiaCharlottesville, VirginiaCharlottesville is an independent city geographically surrounded by but separate from Albemarle County in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States, and named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of King George III of the United Kingdom.The official population estimate for...

- George Rogers Clark Middle School in Vincennes, IndianaVincennes, IndianaVincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the Wabash River in the southwestern part of the state. The population was 18,701 at the 2000 census...

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School of ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

. - George Rogers Clark Elementary School in Paducah, KentuckyPaducah, KentuckyPaducah is the largest city in Kentucky's Jackson Purchase Region and the county seat of McCracken County, Kentucky, United States. It is located at the confluence of the Tennessee River and the Ohio River, halfway between the metropolitan areas of St. Louis, Missouri, to the west and Nashville,...

See also

- History of Louisville, KentuckyHistory of Louisville, KentuckyThe history of Louisville, Kentucky spans hundreds of years, with thousands of years of human habitation. The area's geography and location on the Ohio River attracted people from the earliest times. The city is located at the Falls of the Ohio River...

- List of Louisvillians

- General Jonathan ClarkJonathan Clark (soldier)Jonathan Clark was a U.S. soldier. After serving as a captain, major and colonel in the American Revolutionary War, he rose to the rank of major-general of the Virginia militia...

, his older brother - William Clark (explorer), his younger brother