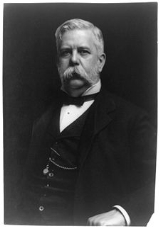

George Westinghouse

Encyclopedia

George Westinghouse, Jr was an American entrepreneur

and engineer

who invented the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry. Westinghouse was one of Thomas Edison

's main rivals in the early implementation of the American electricity system. Westinghouse's system, which used alternating current

based on the extensive research by Nikola Tesla

, ultimately prevailed over Edison's insistence on direct current

. In 1911, he received the AIEE's

Edison Medal "For meritorious achievement in connection with the development of the alternating current system."

Westinghouse was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1980.

. He also devised the Westinghouse Farm Engine

. At age 21 he invented a "car replacer", a device to guide derailed railroad cars back onto the tracks, and a reversible frog, a device used with a railroad switch to guide trains onto one of two tracks.

At about this time he witnessed a train wreck where two engineers saw one another, but were unable to stop their trains in time using the existing brakes. Brakemen ran from car to car, on catwalks atop the cars, applying the brakes manually on each car.

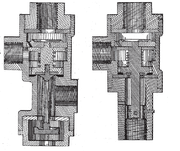

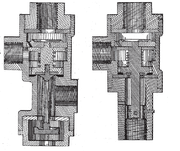

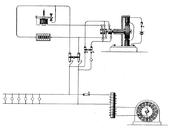

In 1869 at age 22 he invented a railroad braking system using compressed air. The Westinghouse system used a compressor on the locomotive, a reservoir and a special valve on each car, and a single pipe running the length of the train (with flexible connections) which both refilled the reservoirs and controlled the brakes, applying and releasing the brakes on all cars simultaneously. It is a failsafe system, in that any rupture or disconnection in the train pipe will apply the brakes throughout the train. It was patented by Westinghouse on March 5, 1872. The Westinghouse Air Brake Company (WABCO) was subsequently organized to manufacture and sell Westinghouse's invention. It was in time nearly universally adopted. Modern trains use brakes in various forms based on this design.

In 1869 at age 22 he invented a railroad braking system using compressed air. The Westinghouse system used a compressor on the locomotive, a reservoir and a special valve on each car, and a single pipe running the length of the train (with flexible connections) which both refilled the reservoirs and controlled the brakes, applying and releasing the brakes on all cars simultaneously. It is a failsafe system, in that any rupture or disconnection in the train pipe will apply the brakes throughout the train. It was patented by Westinghouse on March 5, 1872. The Westinghouse Air Brake Company (WABCO) was subsequently organized to manufacture and sell Westinghouse's invention. It was in time nearly universally adopted. Modern trains use brakes in various forms based on this design.

Westinghouse pursued many improvements in railway signal

s (then using oil lamps) and in 1881 he founded the Union Switch and Signal Company to manufacture his signaling and switching inventions.

, and realized the need for an electrical distribution system to provide power for lighting. On September 4, 1882, Edison switched on the world's first electrical power distribution system, providing 110 volt

s direct current

(DC) to 59 customers in lower Manhattan

, around his Pearl Street

laboratory.

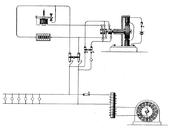

Westinghouse's interests in gas distribution and telephone switching logically led him to become interested in electrical power distribution. He investigated Edison's scheme, but decided that it was too inefficient to be scaled up to a large size. Edison's power network was based on low-voltage DC, which meant large currents and serious power losses. Nikola Tesla

was working on "alternating current

(AC)" power distribution. An AC power system allowed voltages to be "stepped up" by a transformer

for distribution, reducing power losses, and then "stepped down" by a transformer for consumer use.

A power transformer developed by Lucien Gaulard

of France and John Dixon Gibbs of England was demonstrated in London

in 1881, and attracted the interest of Westinghouse. Transformers were not new, but the Gaulard-Gibbs design was one of the first that could handle large amounts of power and was easily manufactured. In 1885 Westinghouse imported a number of Gaulard-Gibbs transformers and a Siemens

AC generator to begin experimenting with AC networks in Pittsburgh.

Assisted by William Stanley, and Franklin Leonard Pope

Assisted by William Stanley, and Franklin Leonard Pope

, Westinghouse worked to refine the transformer design and build a practical AC power network. In 1886 Westinghouse and Stanley installed the first multiple-voltage AC power system in Great Barrington, Massachusetts

. The network was driven by a hydropower

generator that produced 500 volts AC. The voltage was stepped up to 3,000 volts for transmission, and then stepped back down to 100 volts to power electric lights. That same year, Westinghouse formed the "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company", which was renamed the "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in 1889.

Thirty more AC lighting systems were installed within a year, but the scheme was limited by the lack of an effective metering system and an AC electric motor

. In 1888, Westinghouse and his engineer Oliver B. Shallenberger

developed a power meter, with a design that mimicked a gas meter. The same basic meter technology remains in use today. An AC motor was a more difficult task, but a design was already available as Nikola Tesla

had already devised the principles of a polyphase

electric motor. Tesla had conceived the rotating magnetic field

principle in 1882 and used it to invent the first brushless AC motor or induction motor

in 1883, but was employed by Thomas Edison since 1884.

However, by 1886, Tesla and Edison had abruptly parted ways in what would become a well-publicized quarrel, at which point Westinghouse was able to contact Tesla and obtain patent

rights to his AC motor. Westinghouse hired him as a consultant for a year and from 1888 onwards the wide scale introduction of the polyphase AC motor began. The work led to the modern US power-distribution scheme: three-phase AC at 60 Hz, chosen as a rate high enough to minimize light flickering, but low enough to reduce reactive losses, an arrangement also conceived by Tesla.

Westinghouse's promotion of AC power distribution led him into a bitter confrontation with Edison and his DC power system. The feud became known as the "War of Currents

". Edison claimed that high voltage systems were inherently dangerous. Westinghouse replied that the risks could be managed and were outweighed by the benefits. Edison tried to have legislation enacted in several states to limit power transmission voltages to 800 volts, but failed.

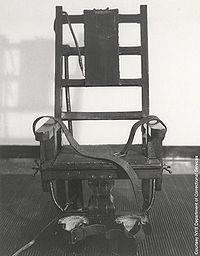

The battle went to an absurd level when, in 1887, a board appointed by the state of New York consulted Edison on the best way to execute condemned prisoners. At first, Edison wanted nothing to do with the matter.

Westinghouse AC networks were clearly winning the battle of the currents, and the ultra-competitive Edison saw a last opportunity to defeat his rival. Edison hired an outside engineer named Harold P. Brown

Westinghouse AC networks were clearly winning the battle of the currents, and the ultra-competitive Edison saw a last opportunity to defeat his rival. Edison hired an outside engineer named Harold P. Brown

, who could pretend to be impartial, to perform public demonstrations in which animals were electrocuted by AC power. Edison then told the state board that AC was so deadly that it would kill instantly, making it the ideal method of execution. His prestige was so great that his recommendation was adopted.

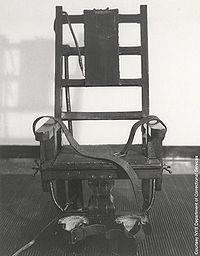

Harold Brown then sold gear for performing electric executions to the state for $8,000. In August 1890, a convict named William Kemmler

became the first person to be executed by electrocution. Westinghouse hired the best lawyer of the day to defend Kemmler and condemned electrocution as a form of "cruel and unusual punishment". Of the first 17 seconds that the current flowed, meant to kill the man, he survived. People were horrified and scrambled to turn the current back on, although no one is quite sure how long the second burst lasted. A reporter got a hold of Westinghouse in Pittsburgh and asked about the execution. "I do not care to talk about it. It has been a brutal affair. They could have done better with an axe." The electric chair

became a common form of execution for decades, although it had been proven to be unsatisfactory for the task. However, Edison failed to coin the term "Westinghoused" for what happened to those sentenced to death.

Edison also failed to discredit AC power, whose advantages outweighed its hazards. Westinghouse was able to build pivotal projects using AC power such as the Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant

in 1891 and the original Niagara Falls Adams Power Plant in 1895 which proved to be a success.

Even General Electric

, which absorbed Edison General Electric in 1892, decided to begin production of AC equipment.

In 1889, Westinghouse hired Benjamin G. Lamme

(1864–1924) electrical engineer and inventor. Interested in mechanics and mathematics from childhood, Lamme graduated from Ohio State University

with an engineering degree (1888). Soon after joining Westinghouse Corp, he became the company's chief designer of electrical machinery. His sister and fellow Ohio State graduate, Bertha Lamme (1869–1943), the nation's first woman electrical engineer, joined him in his pioneering work at Westinghouse until her marriage to fellow Westinghouse engineer, Russel Feicht. Among the electrical generating projects attributed to Bertha Lamme is the turbogenerator at Niagara Falls

. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railway adopted the Lamme's single-phase overhead electrification system in 1905. Benjamin Garver Lamme was Westinghouse's chief engineer from 1903 until his death.

In 1893, in a significant victory, the Westinghouse company was awarded the contract to set up an AC network to power the World's Columbian Exposition

In 1893, in a significant victory, the Westinghouse company was awarded the contract to set up an AC network to power the World's Columbian Exposition

in Chicago

, giving the company and the technology widespread positive publicity. Westinghouse also received a contract to set up the first long-range power network, with AC generators at Niagara Falls

producing electricity for distribution in Buffalo, New York

, 40 kilometres (24.9 mi) away.

With AC networks expanding, Westinghouse turned his attention to electrical power production. At the outset, the available generating sources were hydroturbines where falling water was available, and reciprocating steam engine

s where it was not. Westinghouse felt that reciprocating steam engines were clumsy and inefficient, and wanted to develop some class of "rotating" engine that would be more elegant and efficient.

One of his first inventions had been a rotary steam engine, but it had proven impractical. British engineer Charles Algernon Parsons

began experimenting with steam turbine

s in 1884, beginning with a 10 horsepower (7.5 kW) unit. Westinghouse bought rights to the Parsons turbine in 1885, and improved the Parsons technology and increased its scale.

In 1898 Westinghouse demonstrated a 300 kilowatt unit, replacing reciprocating engines in his air-brake factory. The next year he installed a 1.5 megawatt, 1,200 rpm unit for the Hartford Electric Light Company.

In 1898 Westinghouse demonstrated a 300 kilowatt unit, replacing reciprocating engines in his air-brake factory. The next year he installed a 1.5 megawatt, 1,200 rpm unit for the Hartford Electric Light Company.

Westinghouse then developed steam turbines for maritime propulsion. Large turbines were most efficient at about 3,000 rpm, while an efficient propeller operated at about 100 rpm. That required reduction gearing, but building reduction gearing that could operate at high rpm and at high power was difficult, since a slight misalignment would shake the power train to pieces. Westinghouse and his engineers devised an automatic alignment system that made turbine power practical for large vessels.

Westinghouse remained productive and inventive almost all his life. Like Edison, he had a practical and experimental streak. At one time, Westinghouse began to work on heat pump

s that could provide heating and cooling, and believed that he might be able to extract enough power in the process for the system to run itself.

Any modern engineer would clearly see that Westinghouse was after a perpetual motion machine, and the British physicist Lord Kelvin, one of Westinghouse's correspondents, told him that he would be violating the laws of thermodynamics

. Westinghouse replied that might be the case, but it made no difference. If he couldn't build a perpetual-motion machine, he would still have a heat pump system that he could patent and sell.

With the introduction of the automobile

after the turn of the century, Westinghouse went back to earlier inventions and devised a compressed air shock absorber

for automobile suspensions.

Westinghouse remained a captain of American industry until 1907, when a financial panic led to his resignation from control of the Westinghouse company. By 1911, he was no longer active in business, and his health was in decline.

Westinghouse remained a captain of American industry until 1907, when a financial panic led to his resignation from control of the Westinghouse company. By 1911, he was no longer active in business, and his health was in decline.

George Westinghouse married Marguerite Erskine Walker on August 8, 1867. They had one child, George Westinghouse 3rd, and were married for 47 years. George Westinghouse died on March 12, 1914, in New York City, at age 67. As a Civil War veteran, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

, along with his wife Marguerite, who survived him by three months. Although a shrewd and determined businessman, Westinghouse was a conscientious employer and wanted to make fair deals with his business associates.

In 1918 his former home was razed and the land given to the City of Pittsburgh to establish Westinghouse Park

. In 1930, a memorial to Westinghouse, funded by his employees, was placed in Schenley Park

in Pittsburgh. Also named in his honor, George Westinghouse Bridge

is near the site of his Turtle Creek plant. Its plaque reads:

The George Westinghouse, Jr., Birthplace and Boyhood Home

was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

in 1986.

Entrepreneur

An entrepreneur is an owner or manager of a business enterprise who makes money through risk and initiative.The term was originally a loanword from French and was first defined by the Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon. Entrepreneur in English is a term applied to a person who is willing to...

and engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

who invented the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry. Westinghouse was one of Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

's main rivals in the early implementation of the American electricity system. Westinghouse's system, which used alternating current

Alternating current

In alternating current the movement of electric charge periodically reverses direction. In direct current , the flow of electric charge is only in one direction....

based on the extensive research by Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

, ultimately prevailed over Edison's insistence on direct current

Direct current

Direct current is the unidirectional flow of electric charge. Direct current is produced by such sources as batteries, thermocouples, solar cells, and commutator-type electric machines of the dynamo type. Direct current may flow in a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through...

. In 1911, he received the AIEE's

American Institute of Electrical Engineers

The American Institute of Electrical Engineers was a United States based organization of electrical engineers that existed between 1884 and 1963, when it merged with the Institute of Radio Engineers to form the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers .- History :The 1884 founders of the...

Edison Medal "For meritorious achievement in connection with the development of the alternating current system."

Westinghouse was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1980.

Early years

Westinghouse was born in Central Bridge, NY in 1846. He was the son of a machine shop owner and was talented at machinery and business. He was 19 years old when he created his first invention, the rotary steam engineRotary engine

The rotary engine was an early type of internal-combustion engine, usually designed with an odd number of cylinders per row in a radial configuration, in which the crankshaft remained stationary and the entire cylinder block rotated around it...

. He also devised the Westinghouse Farm Engine

Westinghouse Farm Engine

The Westinghouse Farm Engine was a small, vertical boilered farm engine that emerged in the late nineteenth century. In the transition from horses to machinery, small portable steam engines were hauled by horses from farm to farm. Many small workshops produced them...

. At age 21 he invented a "car replacer", a device to guide derailed railroad cars back onto the tracks, and a reversible frog, a device used with a railroad switch to guide trains onto one of two tracks.

At about this time he witnessed a train wreck where two engineers saw one another, but were unable to stop their trains in time using the existing brakes. Brakemen ran from car to car, on catwalks atop the cars, applying the brakes manually on each car.

Westinghouse pursued many improvements in railway signal

Railway signal

A signal is a mechanical or electrical device erected beside a railway line to pass information relating to the state of the line ahead to train/engine drivers. The driver interprets the signal's indication and acts accordingly...

s (then using oil lamps) and in 1881 he founded the Union Switch and Signal Company to manufacture his signaling and switching inventions.

Electricity and the "War of Currents"

In 1879 Edison invented an improved incandescent light bulbIncandescent light bulb

The incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe makes light by heating a metal filament wire to a high temperature until it glows. The hot filament is protected from air by a glass bulb that is filled with inert gas or evacuated. In a halogen lamp, a chemical process...

, and realized the need for an electrical distribution system to provide power for lighting. On September 4, 1882, Edison switched on the world's first electrical power distribution system, providing 110 volt

Volt

The volt is the SI derived unit for electric potential, electric potential difference, and electromotive force. The volt is named in honor of the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta , who invented the voltaic pile, possibly the first chemical battery.- Definition :A single volt is defined as the...

s direct current

Direct current

Direct current is the unidirectional flow of electric charge. Direct current is produced by such sources as batteries, thermocouples, solar cells, and commutator-type electric machines of the dynamo type. Direct current may flow in a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through...

(DC) to 59 customers in lower Manhattan

Manhattan

Manhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

, around his Pearl Street

Pearl Street (Manhattan)

Pearl Street is a street in the Lower section of the New York City borough of Manhattan, running northeast from Battery Park to the Brooklyn Bridge, then turning west and terminating at Centre Street...

laboratory.

Westinghouse's interests in gas distribution and telephone switching logically led him to become interested in electrical power distribution. He investigated Edison's scheme, but decided that it was too inefficient to be scaled up to a large size. Edison's power network was based on low-voltage DC, which meant large currents and serious power losses. Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

was working on "alternating current

Alternating current

In alternating current the movement of electric charge periodically reverses direction. In direct current , the flow of electric charge is only in one direction....

(AC)" power distribution. An AC power system allowed voltages to be "stepped up" by a transformer

Transformer

A transformer is a device that transfers electrical energy from one circuit to another through inductively coupled conductors—the transformer's coils. A varying current in the first or primary winding creates a varying magnetic flux in the transformer's core and thus a varying magnetic field...

for distribution, reducing power losses, and then "stepped down" by a transformer for consumer use.

A power transformer developed by Lucien Gaulard

Lucien Gaulard

Lucien Gaulard invented devices for the transmission of alternating current electrical energy.-Biography:Gaulard was born in Paris, France....

of France and John Dixon Gibbs of England was demonstrated in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 1881, and attracted the interest of Westinghouse. Transformers were not new, but the Gaulard-Gibbs design was one of the first that could handle large amounts of power and was easily manufactured. In 1885 Westinghouse imported a number of Gaulard-Gibbs transformers and a Siemens

Siemens AG

Siemens AG is a German multinational conglomerate company headquartered in Munich, Germany. It is the largest Europe-based electronics and electrical engineering company....

AC generator to begin experimenting with AC networks in Pittsburgh.

Franklin Leonard Pope

Franklin Leonard Pope was an American engineer, explorer, and inventor.-Biography:He was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the son of Ebenezer Pope and Electra Wainwright. He was a telegrapher, electrical engineer, explorer, inventor, and patent attorney.He was also a major contributor to...

, Westinghouse worked to refine the transformer design and build a practical AC power network. In 1886 Westinghouse and Stanley installed the first multiple-voltage AC power system in Great Barrington, Massachusetts

Great Barrington, Massachusetts

Great Barrington is a town in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 7,104 at the 2010 census. Both a summer resort and home to Ski Butternut, Great Barrington includes the villages of Van...

. The network was driven by a hydropower

Hydropower

Hydropower, hydraulic power, hydrokinetic power or water power is power that is derived from the force or energy of falling water, which may be harnessed for useful purposes. Since ancient times, hydropower has been used for irrigation and the operation of various mechanical devices, such as...

generator that produced 500 volts AC. The voltage was stepped up to 3,000 volts for transmission, and then stepped back down to 100 volts to power electric lights. That same year, Westinghouse formed the "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company", which was renamed the "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in 1889.

Thirty more AC lighting systems were installed within a year, but the scheme was limited by the lack of an effective metering system and an AC electric motor

Electric motor

An electric motor converts electrical energy into mechanical energy.Most electric motors operate through the interaction of magnetic fields and current-carrying conductors to generate force...

. In 1888, Westinghouse and his engineer Oliver B. Shallenberger

Oliver B. Shallenberger

Oliver Blackburn Shallenberger was an American engineer and inventor.He was born in Rochester, Beaver County, Pennsylvania. His parents were Aaron T. Shallenberger and Mary . His uncle was William Shadrack Shallenberger.In 1877 he entered the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. After his...

developed a power meter, with a design that mimicked a gas meter. The same basic meter technology remains in use today. An AC motor was a more difficult task, but a design was already available as Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American inventor, mechanical engineer, and electrical engineer...

had already devised the principles of a polyphase

Polyphase system

A polyphase system is a means of distributing alternating current electrical power. Polyphase systems have three or more energized electrical conductors carrying alternating currents with a definite time offset between the voltage waves in each conductor. Polyphase systems are particularly useful...

electric motor. Tesla had conceived the rotating magnetic field

Rotating magnetic field

A rotating magnetic field is a magnetic field which changes direction at a constant angular rate. This is a key principle in the operation of the alternating-current motor. Nikola Tesla claimed in his autobiography that he identified the concept of the rotating magnetic field in 1882. In 1885,...

principle in 1882 and used it to invent the first brushless AC motor or induction motor

Induction motor

An induction or asynchronous motor is a type of AC motor where power is supplied to the rotor by means of electromagnetic induction. These motors are widely used in industrial drives, particularly polyphase induction motors, because they are robust and have no brushes...

in 1883, but was employed by Thomas Edison since 1884.

However, by 1886, Tesla and Edison had abruptly parted ways in what would become a well-publicized quarrel, at which point Westinghouse was able to contact Tesla and obtain patent

Patent

A patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

rights to his AC motor. Westinghouse hired him as a consultant for a year and from 1888 onwards the wide scale introduction of the polyphase AC motor began. The work led to the modern US power-distribution scheme: three-phase AC at 60 Hz, chosen as a rate high enough to minimize light flickering, but low enough to reduce reactive losses, an arrangement also conceived by Tesla.

Westinghouse's promotion of AC power distribution led him into a bitter confrontation with Edison and his DC power system. The feud became known as the "War of Currents

War of Currents

In the "War of Currents" era in the late 1880s, George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison became adversaries due to Edison's promotion of direct current for electric power distribution over alternating current advocated by several European companies and Westinghouse Electric based out of Pittsburgh,...

". Edison claimed that high voltage systems were inherently dangerous. Westinghouse replied that the risks could be managed and were outweighed by the benefits. Edison tried to have legislation enacted in several states to limit power transmission voltages to 800 volts, but failed.

The battle went to an absurd level when, in 1887, a board appointed by the state of New York consulted Edison on the best way to execute condemned prisoners. At first, Edison wanted nothing to do with the matter.

Harold P. Brown

Harold Pitney Brown was the American credited with building the original electric chair based on the design by Dr. Alfred P. Southwick...

, who could pretend to be impartial, to perform public demonstrations in which animals were electrocuted by AC power. Edison then told the state board that AC was so deadly that it would kill instantly, making it the ideal method of execution. His prestige was so great that his recommendation was adopted.

Harold Brown then sold gear for performing electric executions to the state for $8,000. In August 1890, a convict named William Kemmler

William Kemmler

William Francis Kemmler of Buffalo, New York, was a convicted murderer and the first person in the world to be executed using an electric chair.-Early life:...

became the first person to be executed by electrocution. Westinghouse hired the best lawyer of the day to defend Kemmler and condemned electrocution as a form of "cruel and unusual punishment". Of the first 17 seconds that the current flowed, meant to kill the man, he survived. People were horrified and scrambled to turn the current back on, although no one is quite sure how long the second burst lasted. A reporter got a hold of Westinghouse in Pittsburgh and asked about the execution. "I do not care to talk about it. It has been a brutal affair. They could have done better with an axe." The electric chair

Electric chair

Execution by electrocution, usually performed using an electric chair, is an execution method originating in the United States in which the condemned person is strapped to a specially built wooden chair and electrocuted through electrodes placed on the body...

became a common form of execution for decades, although it had been proven to be unsatisfactory for the task. However, Edison failed to coin the term "Westinghoused" for what happened to those sentenced to death.

Edison also failed to discredit AC power, whose advantages outweighed its hazards. Westinghouse was able to build pivotal projects using AC power such as the Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant

Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant

The Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant, located near Ophir, Colorado, was the world's first commercial system to produce and transmit alternating current electricity. It is now on the List of IEEE Milestones....

in 1891 and the original Niagara Falls Adams Power Plant in 1895 which proved to be a success.

Even General Electric

General Electric

General Electric Company , or GE, is an American multinational conglomerate corporation incorporated in Schenectady, New York and headquartered in Fairfield, Connecticut, United States...

, which absorbed Edison General Electric in 1892, decided to begin production of AC equipment.

In 1889, Westinghouse hired Benjamin G. Lamme

Benjamin G. Lamme

Benjamin Garver Lamme was an electrical engineer and chief engineer at Westinghouse, where he was responsible for the design of electrical power machines...

(1864–1924) electrical engineer and inventor. Interested in mechanics and mathematics from childhood, Lamme graduated from Ohio State University

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly referred to as Ohio State, is a public research university located in Columbus, Ohio. It was originally founded in 1870 as a land-grant university and is currently the third largest university campus in the United States...

with an engineering degree (1888). Soon after joining Westinghouse Corp, he became the company's chief designer of electrical machinery. His sister and fellow Ohio State graduate, Bertha Lamme (1869–1943), the nation's first woman electrical engineer, joined him in his pioneering work at Westinghouse until her marriage to fellow Westinghouse engineer, Russel Feicht. Among the electrical generating projects attributed to Bertha Lamme is the turbogenerator at Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls

The Niagara Falls, located on the Niagara River draining Lake Erie into Lake Ontario, is the collective name for the Horseshoe Falls and the adjacent American Falls along with the comparatively small Bridal Veil Falls, which combined form the highest flow rate of any waterfalls in the world and has...

. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railway adopted the Lamme's single-phase overhead electrification system in 1905. Benjamin Garver Lamme was Westinghouse's chief engineer from 1903 until his death.

Later years

World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition was a World's Fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. Chicago bested New York City; Washington, D.C.; and St...

in Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, giving the company and the technology widespread positive publicity. Westinghouse also received a contract to set up the first long-range power network, with AC generators at Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls

The Niagara Falls, located on the Niagara River draining Lake Erie into Lake Ontario, is the collective name for the Horseshoe Falls and the adjacent American Falls along with the comparatively small Bridal Veil Falls, which combined form the highest flow rate of any waterfalls in the world and has...

producing electricity for distribution in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

, 40 kilometres (24.9 mi) away.

With AC networks expanding, Westinghouse turned his attention to electrical power production. At the outset, the available generating sources were hydroturbines where falling water was available, and reciprocating steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

s where it was not. Westinghouse felt that reciprocating steam engines were clumsy and inefficient, and wanted to develop some class of "rotating" engine that would be more elegant and efficient.

One of his first inventions had been a rotary steam engine, but it had proven impractical. British engineer Charles Algernon Parsons

Charles Algernon Parsons

Sir Charles Algernon Parsons OM KCB FRS was an Anglo-Irish engineer, best known for his invention of the steam turbine. He worked as an engineer on dynamo and turbine design, and power generation, with great influence on the naval and electrical engineering fields...

began experimenting with steam turbine

Steam turbine

A steam turbine is a mechanical device that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam, and converts it into rotary motion. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Parsons in 1884....

s in 1884, beginning with a 10 horsepower (7.5 kW) unit. Westinghouse bought rights to the Parsons turbine in 1885, and improved the Parsons technology and increased its scale.

Westinghouse then developed steam turbines for maritime propulsion. Large turbines were most efficient at about 3,000 rpm, while an efficient propeller operated at about 100 rpm. That required reduction gearing, but building reduction gearing that could operate at high rpm and at high power was difficult, since a slight misalignment would shake the power train to pieces. Westinghouse and his engineers devised an automatic alignment system that made turbine power practical for large vessels.

Westinghouse remained productive and inventive almost all his life. Like Edison, he had a practical and experimental streak. At one time, Westinghouse began to work on heat pump

Heat pump

A heat pump is a machine or device that effectively "moves" thermal energy from one location called the "source," which is at a lower temperature, to another location called the "sink" or "heat sink", which is at a higher temperature. An air conditioner is a particular type of heat pump, but the...

s that could provide heating and cooling, and believed that he might be able to extract enough power in the process for the system to run itself.

Any modern engineer would clearly see that Westinghouse was after a perpetual motion machine, and the British physicist Lord Kelvin, one of Westinghouse's correspondents, told him that he would be violating the laws of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a physical science that studies the effects on material bodies, and on radiation in regions of space, of transfer of heat and of work done on or by the bodies or radiation...

. Westinghouse replied that might be the case, but it made no difference. If he couldn't build a perpetual-motion machine, he would still have a heat pump system that he could patent and sell.

With the introduction of the automobile

Automobile

An automobile, autocar, motor car or car is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transporting passengers, which also carries its own engine or motor...

after the turn of the century, Westinghouse went back to earlier inventions and devised a compressed air shock absorber

Shock absorber

A shock absorber is a mechanical device designed to smooth out or damp shock impulse, and dissipate kinetic energy. It is a type of dashpot.-Nomenclature:...

for automobile suspensions.

George Westinghouse married Marguerite Erskine Walker on August 8, 1867. They had one child, George Westinghouse 3rd, and were married for 47 years. George Westinghouse died on March 12, 1914, in New York City, at age 67. As a Civil War veteran, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

, along with his wife Marguerite, who survived him by three months. Although a shrewd and determined businessman, Westinghouse was a conscientious employer and wanted to make fair deals with his business associates.

In 1918 his former home was razed and the land given to the City of Pittsburgh to establish Westinghouse Park

Westinghouse Park

Westinghouse Park is a small municipal park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.The park's lands are the site of the former mansion, "Solitude", which was home to George Westinghouse, an American entrepreneur and engineer....

. In 1930, a memorial to Westinghouse, funded by his employees, was placed in Schenley Park

Schenley Park

Schenley Park is a large municipal park located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, between the neighborhoods of Oakland, Greenfield, and Squirrel Hill. It is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district...

in Pittsburgh. Also named in his honor, George Westinghouse Bridge

George Westinghouse Bridge

George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania carries U.S. Route 30, The Lincoln Highway, over the Turtle Creek Valley where it joins the Monongahela River Valley east of Pittsburgh....

is near the site of his Turtle Creek plant. Its plaque reads:

|

The George Westinghouse, Jr., Birthplace and Boyhood Home

George Westinghouse, Jr., Birthplace and Boyhood Home

George Westinghouse, Jr., Birthplace and Boyhood Home is a historic home located at Central Bridge in Schoharie County, New York. The property includes two 19th-century residences, two small barns, a well house and privy, as well as the site of a combined blacksmith shop and threshing machine works...

was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

in 1986.