Greek Resistance

Encyclopedia

The Greek Resistance is the blanket term for a number of armed and unarmed groups from across the political spectrum that resisted the Axis Occupation of Greece in the period 1941–1944, during World War II

.

and occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany

(and its allies Italy and Bulgaria

) from 1941-1944. Italy led the way with its attempted invasion

from Albania

in 1940, which was repelled by the Greek Army. After the German invasion

, the occupation of Athens and the fall of Crete, King George II

and his government escaped to Egypt

, where they proclaimed a government-in-exile, recognised by the Allies

, but not the Soviet Union

which was at the time friendly to the Nazi Germany

after the signature of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The British actively encouraged, even coerced, the King to appoint centrist, moderate ministers; only two of his ministers were members of the dictatorial government

that had governed Greece before the German invasion. Despite that some in the left-wing resistance claimed the government to be illegitimate, on account of its roots in the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas

from 1936-1941.

The Germans set up a Greek collaborationist government, headed by General Georgios Tsolakoglou

, before entering Athens

. Some high-profile officers of the pre-war Greek regime served the Germans in various posts.This government however, lacked legitimacy and support, being utterly dependent on the German and Italian occupation authorities, and discredited because of its inability to prevent the cession of much of Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace

to Bulgaria

. Both the collaborationist government and the occupation forces were further undermined due to their failure to prevent the outbreak of the Great Famine

, with the mortality rate reaching a peak in the winter of 1941-42, which seriously harmed the Greek civilian population.

Although there is an unconfirmed incident connected with Evzone Konstantinos Koukidis

Although there is an unconfirmed incident connected with Evzone Konstantinos Koukidis

the day the Germans occupied Athens, the first confirmed resistance act in Greece had taken place on the night of 30 May 1941, even before the end of the Battle of Crete

. Two young students, Apostolos Santas

, a law student

, and Manolis Glezos

, a student at the Athens University of Economics and Business, secretly climbed the northwest face of the Acropolis

and tore down the swastika banner

which had been placed there by the occupation authorities.

The first wider resistance movements occurred in northern Greece, where the Bulgarians annexed Greek territories. The first mass uprising occurred around the town of Drama

in eastern Macedonia, in the Bulgaria

n occupation zone. The Bulgarian authorities had initiated large-scale Bulgarization policies, causing the Greek population's reaction. During the night of 28–29 September 1941 the people of Drama

and its outskirts rose up. This badly-organized revolt was suppressed by the Bulgarian Army, which retaliated executing over three thousand people in Drama alone. An estimated fifteen thousand Greeks were killed from the Bulgarian occupational army during the next few weeks and in the countryside entire villages were machine gunned and looted. The town of Doxato

and the village of Choristi are officially considered today Martyr Cities.

At the same time, large demonstrations were organized in Greek Macedonian cities by the Defenders of Northern Greece (YVE), a right-wing organization, in protest against the Bulgarian annexation

of Greek territories.

Armed groups consisted of andartes - αντάρτες ("guerillas") first appeared in the mountains of Macedonia

by October 1941, and the first armed clashes resulted in 488 civilians being murdered in reprisal

s by the Germans, which succeeded in severely limiting Resistance activity for the next few months. However, these harsh actions, together with the plundering of Greece's natural resources by the Germans, turned Greeks more against the occupiers.

, and those who remained behind were unsure of their prospects against the Wehrmacht. This situation resulted in the creation of several new groupings, where the pre-war establishment was largely absent, which assumed the role of resisting the occupation powers.

The first major resistance group to be founded was the National Liberation Front (EAM). EAM was a political movement. Until 1944 EAM became the most powerful resistance movement in Europe, with more than 1,800,000 members (the Greek population was around 7,500,000 at that time). EAM was organized by the Greek Communist Party (KKE) and other smaller parties, but all major political parties refused to participate either in EAM or in any other resistance movement. On February 16, 1942, EAM gave permission to a communist veteran, called Thanasis Claras (later known as Aris Velouchiotis

) to examine the possibilities of a victorious armed resistance movement. Soon the first andartes (guerrillas) joined ELAS and many battles were fought and won against both the Italians and Nazis (the sabotage of Gorgopotamos bridge [with the participation of EDES partisans and British commandos of SOE], the battle at Mikro Horio etc.).

The second to be found was Venizelist

-oriented National Republican Greek League (EDES), led by a former army officer, Colonel Napoleon Zervas

, with exiled republican

General Nikolaos Plastiras

as its nominal head. Although its foundation was announced in late 1941, there were no military acts until 1942, when ELAS (National Popular Liberation Army) the armed forces of EAM came to birth.

. But by 1942, due to the weakness of the central government in Athens, the countryside was gradually slipping out of its control, while the Resistance groups had acquired a firm and wide-ranging organization, parallel and more effective than that of the official state.

, with Aris Velouchiotis

a communist activist as their chief captain. Later, on 28 July 1942, a centrist ex-army officer Col.Napoleon Zervas

announced the foundation of the "National Groups of Greek Guerrillas" (EOEA), as EDES' military arm, to operate, at first, in the region of Aetoloakarnania. EKKA also formed a military corps, named after the famous 5/42 Evzone Regiment, under Col. Dimitrios Psarros

, that was mainly localized in the area of Mount Giona

.

Until the summer of 1942, the occupation authorities had been little troubled by the armed Resistance, which was still in its infancy. The Italians in particular, in control of most of the countryside, considered the situation to have been normalized. From that point, however, the Resistance gained pace, with EAM/ELAS in particular expanding rapidly, with armed groups attacking and disarming local gendarmerie stations and isolated Italian outposts, or touring the villages and giving speeches. The Italians were forced to re-evaluate their assessment, and take such measures such as the deportation of Army officers to camps in Italy and Germany, which naturally only encouraged the latter to join the underground en masse by escaping "to the mountains".

Until the summer of 1942, the occupation authorities had been little troubled by the armed Resistance, which was still in its infancy. The Italians in particular, in control of most of the countryside, considered the situation to have been normalized. From that point, however, the Resistance gained pace, with EAM/ELAS in particular expanding rapidly, with armed groups attacking and disarming local gendarmerie stations and isolated Italian outposts, or touring the villages and giving speeches. The Italians were forced to re-evaluate their assessment, and take such measures such as the deportation of Army officers to camps in Italy and Germany, which naturally only encouraged the latter to join the underground en masse by escaping "to the mountains".

These developments emerged most dramatically as the Greek Resistance announced its presence to the world with one of the war's most spectacular sabotage acts, the blowing up of the Gorgopotamos

railway bridge, linking northern and southern Greece, on 25 November 1942. This operation was the result of British mediation between ELAS and EDES (Operation "Harling"

), carried out by 12 British Special Operations Executive

(SOE) saboteur

s and a joint ELAS-EDES force. This was the first and last time that the two major Resistance groups would cooperate, due to the rapidly developing rivalry and ideological retrenchment between them.

, Grevena

, Trikkala, Metsovon and others were liberated by July. The Axis forces and their collaborators

remained in control only of the main towns and the connecting roads, with the interior left to the andartes. This was "Free Greece", stretching from the Ionian Sea

to the Aegean

and from the borders of the German zone in Macedonia to Boeotia

, a territory of 30,000 km² and 750,000 inhabitants.

. EDES was limited in operations to Epirus

, and EKKA operated in a small area in Central Greece. The Italian capitulation

in September 1943 provided a windfall for the Resistance, as the Italian Army in many places simply disintegrated. Most Italian troops were swiftly disarmed and interned by the Germans, but in many places significant amounts of weaponry and equipment, as well as men, fell into the hands of the Resistance. The most spectacular case was that of the Pinerolo division and the Aosta Cavalry Regiment, which went completely over to the EAMite andartes.

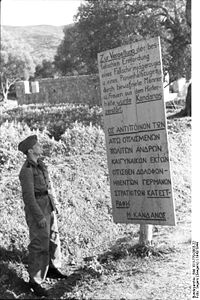

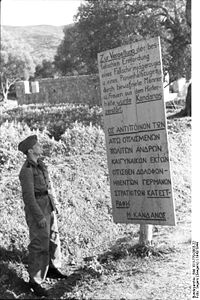

The Germans now took over the Italian zone, and soon proved to be a totally different opponent from the demoralized, war-weary and far less brutal Italians. Already since the early summer of 1943, German troops had been pouring into Greece, fearing an Allied landing there (in fact falling victims to a grand-scale Allied strategic deception operation, "Operation Barclay

"). Soon they became involved in wide-ranging counterguerrilla

operations, which they carried out with great ruthlessness, based on their experiences in Yugoslavia. In the course of these operations, mass reprisal

s were carried out, resulting in war crimes such as at Kommeno

on August 16, the Massacre of Kalavryta

in December and the Massacre of Distomo in June 1944. At the same time, hundreds of villages were systematically torched and almost one million people left homeless.

" between Winston Churchill

and Joseph Stalin

in October 1944. EAM on its part considered itself "the only true resistance group". Its leadership was intensely distrustful of British policies for Greece, and viewed Zervas' contacts with London and the Greek government with suspicion.

At the same time, EAM found itself under attack by the Germans and their collaborators. Dominated by the old political class, and looking already to the oncoming post-Liberation era, the new Ioannis Rallis

government had established the notorious Security Battalions

, with the blessing of the German authorities, in order to fight exclusively against ELAS. Other anti-communist resistance groups, such as the royalist Organization "X"

, were also reinforced, receiving arms and funding by the British.

A virtual civil war was now being waged under the eyes of the Germans. In October 1943, ELAS attacked EDES in Epirus

, where the latter organization was the dominant resistance group, by transferring units from the neighbouring regions. This conflict continued until February 1944, when the British mission in Greece succeeded in negotiating a ceasefire (the Plaka agreement) which in the event proved to be only temporary. The attack led to an unofficial truce between EDES and the German forces in Epirus under General Hubert Lanz

. But the fight continued amongst ELAS and the other minor resistance groups (like "X"), as well as against the Security Battalions, even in the streets of Athens, until the German withdrawal in October 1944. In March, EAM established its own rival government in Free Greece, the Political Committee of National Liberation

, clearly staking its claim to a dominant role in post-war Greece. Consequently, on Easter Monday, 17 April 1944, ELAS forces attacked and destroyed the EKKA's 5/42 Regiment, capturing and executing many of its men, including its leader Colonel Dimitrios Psarros

. The event caused a major shock in the Greek political scene, since Psarros was a well-known republican, patriot and anti-royalist. For EAM-ELAS, this act was fatal, as it strengthened suspicion of its intentions for the post-Occupation period, and drove many liberals and moderates, especially in the cities, against it, cementing the emerging rift in Greek society between pro- and anti-EAM segments.

The resistance in Crete was centred in the mountainous interior, and despite the heavy presence of German troops, developed significant activity. Notable figures of the Cretan Resistance include Patrick Leigh Fermor

The resistance in Crete was centred in the mountainous interior, and despite the heavy presence of German troops, developed significant activity. Notable figures of the Cretan Resistance include Patrick Leigh Fermor

and George Psychoundakis

. Resistance operations included the abduction

of General Heinrich Kreipe

by Patrick Leigh Fermor

and Bill Stanley Moss

and the battle of Trahili.

and the Gestapo

, and confessions used to roll up networks. The job of wireless operators was perhaps the most dangerous, since the Germans used direction-finding equipment to pinpoint the location of transmitters; operators were often shot on the spot, and those were the lucky ones, since immediate execution prevented torture.

, and marked the awakening of the spirit of Resistance amongst the wider urban population. Soon after, from 12–14 April, the "TTT" (Telecommunications & Postal) workers began a strike in Athens, which spread throughout the country. Initially, the strikers' demands were financial, but it quickly assumed a political aspect, as the strike was encouraged by EAM's labour union organization, EEAM. Finally, the strike ended on April 21, with the full capitulation of the collaborationist government to the strikers' demands, including the immediate release of arrested strike leaders.

In early 1943, rumours spread of a planned mobilization of the labour force by the occupation authorities, with the intent of sending them to work in Germany

. The first reactions began amongst students on 7 February, but soon grew in scope and volume. Throughout February, successive strikes and demonstrations paralyzed Athens, culminating in a massive rally on the 24th. The tense climate was amply displayed at the funeral of Greece's national poet, Kostis Palamas

, on 28 February, which turned into an anti-Axis demonstration.

The resistance also involved risks for ordinary Greeks. Attacks often incited reprisal

killings of civilians by the German occupying forces. Villages were burned and its inhabitants massacred. The Germans also resorted to hostage taking. There were also accusations that many of ELAS' attacks against German soldiers didn't happen for resistance reasons but aiming the destuction of specific villages and the recruitment of their men. Quotas were even introduced determining the number of civilians or hostages to be killed in response to the death or wounding of German soldiers.

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Origins

The rise of resistance movements in Greece was precipitated by the invasionBattle of Greece

The Battle of Greece is the common name for the invasion and conquest of Greece by Nazi Germany in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth forces, while the Germans' Axis allies Italy and Bulgaria played secondary roles...

and occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

(and its allies Italy and Bulgaria

Military history of Bulgaria during World War II

The military history of Bulgaria during World War II encompasses an initial period of neutrality until 1 March 1941, a period of alliance with the Axis Powers until 9 September 1944 and a period of alignment with the Allies until the end of the war. Bulgaria was a constitutional monarchy during...

) from 1941-1944. Italy led the way with its attempted invasion

Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War was a conflict between Italy and Greece which lasted from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. It marked the beginning of the Balkans Campaign of World War II...

from Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

in 1940, which was repelled by the Greek Army. After the German invasion

Battle of Greece

The Battle of Greece is the common name for the invasion and conquest of Greece by Nazi Germany in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth forces, while the Germans' Axis allies Italy and Bulgaria played secondary roles...

, the occupation of Athens and the fall of Crete, King George II

George II of Greece

George II reigned as King of Greece from 1922 to 1924 and from 1935 to 1947.-Early life, first period of kingship and exile:George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near Athens, the eldest son of King Constantine I of Greece and his wife, Princess Sophia of Prussia...

and his government escaped to Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, where they proclaimed a government-in-exile, recognised by the Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

, but not the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

which was at the time friendly to the Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

after the signature of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The British actively encouraged, even coerced, the King to appoint centrist, moderate ministers; only two of his ministers were members of the dictatorial government

4th of August Regime

The 4th of August Regime , commonly also known as the Metaxas Regime , was an authoritarian regime under the leadership of General Ioannis Metaxas that ruled Greece from 1936 to 1941...

that had governed Greece before the German invasion. Despite that some in the left-wing resistance claimed the government to be illegitimate, on account of its roots in the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas was a Greek general, politician, and dictator, serving as Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941...

from 1936-1941.

The Germans set up a Greek collaborationist government, headed by General Georgios Tsolakoglou

Georgios Tsolakoglou

Georgios Tsolakoglou was a Greek military officer who became the first Prime Minister of the Greek collaborationist government during the Axis Occupation in 1941-1942.-Military career:...

, before entering Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

. Some high-profile officers of the pre-war Greek regime served the Germans in various posts.This government however, lacked legitimacy and support, being utterly dependent on the German and Italian occupation authorities, and discredited because of its inability to prevent the cession of much of Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace

Western Thrace

Western Thrace or simply Thrace is a geographic and historical region of Greece, located between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country. Together with the regions of Macedonia and Epirus, it is often referred to informally as northern Greece...

to Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

. Both the collaborationist government and the occupation forces were further undermined due to their failure to prevent the outbreak of the Great Famine

Great Famine (Greece)

The Great Famine was a period of mass starvation in Axis-occupied Greece, during World War II . The local population suffered greatly during this period, while the Axis Powers initiated a policy of large scale plunder...

, with the mortality rate reaching a peak in the winter of 1941-42, which seriously harmed the Greek civilian population.

First resistance acts

Konstantinos Koukidis

Konstantinos Koukidis was the Greek Evzone on flag guard duty on the 27th of April 1941 at the Athens Acropolis, at the beginning of the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II. After the first Germans climbed up the Acropolis, an officer ordered him to surrender, give up the Greek flag and...

the day the Germans occupied Athens, the first confirmed resistance act in Greece had taken place on the night of 30 May 1941, even before the end of the Battle of Crete

Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete was a battle during World War II on the Greek island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May 1941, when Nazi Germany launched an airborne invasion of Crete under the code-name Unternehmen Merkur...

. Two young students, Apostolos Santas

Apostolos Santas

Apostolos Santas commonly known as Lakis, was a Greek veteran of the Resistance against the Axis Occupation of Greece during World War II, most notable for his participation, along with Manolis Glezos, in the taking down of the German flag from the Acropolis on 30 May 1941.Apostolos Santas was...

, a law student

Law school

A law school is an institution specializing in legal education.- Law degrees :- Canada :...

, and Manolis Glezos

Manolis Glezos

Manolis Glezos is a Greek left wing politician and writer, worldwide known especially for his participation in the World War II resistance.- 1939 - 1945 :...

, a student at the Athens University of Economics and Business, secretly climbed the northwest face of the Acropolis

Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens or Citadel of Athens is the best known acropolis in the world. Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification...

and tore down the swastika banner

Reichskriegsflagge

Reichskriegsflagge was the official name of the war flag used by the German armed forces from 1867 to 1945. A total of seven different designs were used during this period.-Imperial Germany:...

which had been placed there by the occupation authorities.

The first wider resistance movements occurred in northern Greece, where the Bulgarians annexed Greek territories. The first mass uprising occurred around the town of Drama

Drama, Greece

Drama , the ancient Drabescus , is a town and municipality in northeastern Greece. Drama is the capital of the peripheral unit of Drama which is part of the East Macedonia and Thrace periphery. The town is the economic center of the municipality , which in turn comprises 53.5 percent of the...

in eastern Macedonia, in the Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

n occupation zone. The Bulgarian authorities had initiated large-scale Bulgarization policies, causing the Greek population's reaction. During the night of 28–29 September 1941 the people of Drama

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" , which is derived from "to do","to act" . The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a...

and its outskirts rose up. This badly-organized revolt was suppressed by the Bulgarian Army, which retaliated executing over three thousand people in Drama alone. An estimated fifteen thousand Greeks were killed from the Bulgarian occupational army during the next few weeks and in the countryside entire villages were machine gunned and looted. The town of Doxato

Doxato

Doxato is a town and municipality in the Drama peripheral unit, in East Macedonia and Thrace, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Kalampaki.-Municipality:...

and the village of Choristi are officially considered today Martyr Cities.

At the same time, large demonstrations were organized in Greek Macedonian cities by the Defenders of Northern Greece (YVE), a right-wing organization, in protest against the Bulgarian annexation

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

of Greek territories.

Armed groups consisted of andartes - αντάρτες ("guerillas") first appeared in the mountains of Macedonia

Macedonia (Greece)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of Greece in Southern Europe. Macedonia is the largest and second most populous Greek region...

by October 1941, and the first armed clashes resulted in 488 civilians being murdered in reprisal

Reprisal

In international law, a reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Reprisals in the laws of war are extremely limited, as they commonly breached the rights of civilians, an action outlawed by the Geneva...

s by the Germans, which succeeded in severely limiting Resistance activity for the next few months. However, these harsh actions, together with the plundering of Greece's natural resources by the Germans, turned Greeks more against the occupiers.

Establishment of the first resistance groups

The lack of a legitimate government and the inactivity of the established political class created a power vacuum and meant an absence of a rallying point for the Greek people. Most officers and citizens who wanted to continue the fight fled to the British-controlled Middle EastMiddle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, and those who remained behind were unsure of their prospects against the Wehrmacht. This situation resulted in the creation of several new groupings, where the pre-war establishment was largely absent, which assumed the role of resisting the occupation powers.

The first major resistance group to be founded was the National Liberation Front (EAM). EAM was a political movement. Until 1944 EAM became the most powerful resistance movement in Europe, with more than 1,800,000 members (the Greek population was around 7,500,000 at that time). EAM was organized by the Greek Communist Party (KKE) and other smaller parties, but all major political parties refused to participate either in EAM or in any other resistance movement. On February 16, 1942, EAM gave permission to a communist veteran, called Thanasis Claras (later known as Aris Velouchiotis

Aris Velouchiotis

Aris Velouchiotis , the nom de guerre of Athanasios Klaras , was the most prominent leader and chief instigator of the Greek People's Liberation Army , the military branch of the National Liberation Front , which was the major resistance organization in occupied Greece from 1942 to 1945...

) to examine the possibilities of a victorious armed resistance movement. Soon the first andartes (guerrillas) joined ELAS and many battles were fought and won against both the Italians and Nazis (the sabotage of Gorgopotamos bridge [with the participation of EDES partisans and British commandos of SOE], the battle at Mikro Horio etc.).

The second to be found was Venizelist

Venizelism

Venizelism was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid 1970s.- Ideology :Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:*Opposition to Monarchy...

-oriented National Republican Greek League (EDES), led by a former army officer, Colonel Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas was a Greek general and resistance leader during World War II. He organized and led the National Republican Greek League , the second most significant , in terms of size and activity, resistance organization against the Axis Occupation of Greece.-Early life and army career:Zervas...

, with exiled republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

General Nikolaos Plastiras

Nikolaos Plastiras

Nikolaos Plastiras was a Greek general and politician, who served thrice as Prime Minister of Greece. A distinguished soldier and known for his personal bravery, he was known as "O Mavros Kavalaris" during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922...

as its nominal head. Although its foundation was announced in late 1941, there were no military acts until 1942, when ELAS (National Popular Liberation Army) the armed forces of EAM came to birth.

Resistance in the mountains - Andartiko

Greece is a mountainous country, with a long tradition in andartiko (αντάρτικο, "guerrilla warfare"), dating back to the days of the klephts (anti-Turkish bandits) of the Ottoman period, who often enjoyed folk-hero status. In the 1940s, the countryside was poor, the road network not very well developed, and state control outside the cities usually exercised by the Greek GendarmerieGreek Gendarmerie

The Hellenic Gendarmerie was the national gendarmerie and military police force of Greece.-19th Century:The Greek Gendarmerie was established after the enthronement of King Otto in 1833 as the Royal Gendarmerie and modeled after the French Gendarmerie. It was at that time formally part of the...

. But by 1942, due to the weakness of the central government in Athens, the countryside was gradually slipping out of its control, while the Resistance groups had acquired a firm and wide-ranging organization, parallel and more effective than that of the official state.

Emergence of the armed resistance

In February 1942, EAM, an organization controlled by the local Communist Party formed a military corps, called the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS), that would first operate in the mountains of Central GreeceCentral Greece

Continental Greece or Central Greece , colloquially known as Roúmeli , is a geographical region of Greece. Its territory is divided into the administrative regions of Central Greece, Attica, and part of West Greece...

, with Aris Velouchiotis

Aris Velouchiotis

Aris Velouchiotis , the nom de guerre of Athanasios Klaras , was the most prominent leader and chief instigator of the Greek People's Liberation Army , the military branch of the National Liberation Front , which was the major resistance organization in occupied Greece from 1942 to 1945...

a communist activist as their chief captain. Later, on 28 July 1942, a centrist ex-army officer Col.Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas

Napoleon Zervas was a Greek general and resistance leader during World War II. He organized and led the National Republican Greek League , the second most significant , in terms of size and activity, resistance organization against the Axis Occupation of Greece.-Early life and army career:Zervas...

announced the foundation of the "National Groups of Greek Guerrillas" (EOEA), as EDES' military arm, to operate, at first, in the region of Aetoloakarnania. EKKA also formed a military corps, named after the famous 5/42 Evzone Regiment, under Col. Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros was a Greek army officer and resistance leader. He was the founder and leader of the resistance group National and Social Liberation , the third-most significant organization of the Greek Resistance movement after the National Liberation Front and the National Republican Greek...

, that was mainly localized in the area of Mount Giona

Mount Giona

Mount Giona is a mountain in Central Greece, in the prefecture of Phocis, located between the mountains of Parnassus and Vardousia. Known in classical antiquity as the Aselinon Oros , it is the highest mountain south of Olympus and the fifth overall in Greece...

.

These developments emerged most dramatically as the Greek Resistance announced its presence to the world with one of the war's most spectacular sabotage acts, the blowing up of the Gorgopotamos

Gorgopotamos

Gorgopotamos is a village and a former municipality in Phthiotis, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Lamia, of which it is a municipal unit. It is located 10 km southwest of Lamia. Its 2001 population was 443 for the village and 4,510 for the...

railway bridge, linking northern and southern Greece, on 25 November 1942. This operation was the result of British mediation between ELAS and EDES (Operation "Harling"

Operation Harling

Operation Harling was a World War II mission by the British Special Operations Executive , in cooperation with the Greek Resistance groups ELAS and EDES, which destroyed the heavily guarded Gorgopotamos viaduct in Central Greece on 25 November 1942...

), carried out by 12 British Special Operations Executive

Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive was a World War II organisation of the United Kingdom. It was officially formed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton on 22 July 1940, to conduct guerrilla warfare against the Axis powers and to instruct and aid local...

(SOE) saboteur

Saboteur

A saboteur is someone who commits sabotage.It may also refer to:*Morituri , a 1965 film also known as The Saboteur*Saboteur , a card game by Frederic Moyersoen, published in 2004...

s and a joint ELAS-EDES force. This was the first and last time that the two major Resistance groups would cooperate, due to the rapidly developing rivalry and ideological retrenchment between them.

The establishment of "Free Greece"

Nevertheless, constant attacks and acts of sabotage followed against the Italians, such as the Battle of Fardykampos, resulting in the capture of several hundred Italian soldiers and significant amounts of equipment. By the late spring of 1943, the Italians were forced to withdraw from several areas. The towns of KarditsaKarditsa

Karditsa is a city in western Thessaly in mainland Greece. The city of Karditsa is the capital of Karditsa peripheral unit.Inhabitation is attested from 9000 BCE. Karditsa ls linked with GR-30, the road to Karpenisi, and the road to Palamas and Larissa...

, Grevena

Grevena

Grevena is a town and municipality in Greece, capital of the Grevena peripheral unit. The town's current population is 10,447 citizens; it lies about 400 km from Athens and about 180 km from Thessaloniki. The municipality's population is 30,564...

, Trikkala, Metsovon and others were liberated by July. The Axis forces and their collaborators

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

remained in control only of the main towns and the connecting roads, with the interior left to the andartes. This was "Free Greece", stretching from the Ionian Sea

Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea , is an arm of the Mediterranean Sea, south of the Adriatic Sea. It is bounded by southern Italy including Calabria, Sicily and the Salento peninsula to the west, southern Albania to the north, and a large number of Greek islands, including Corfu, Zante, Kephalonia, Ithaka, and...

to the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

and from the borders of the German zone in Macedonia to Boeotia

Boeotia

Boeotia, also spelled Beotia and Bœotia , is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. It was also a region of ancient Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, the second largest city being Thebes.-Geography:...

, a territory of 30,000 km² and 750,000 inhabitants.

Italian collapse and German takeover

By this time (July 1943), the overall strength of the andartes was around 20-30,000, with most belonging to the ELAS, newly under the command of General Stefanos SarafisStefanos Sarafis

Stefanos Sarafis was an officer of the Hellenic Army who played an important role during the Greek Resistance.- Early life and career :Sarafis was born at Trikala in 1890, and studied law in the University of Athens. During the Balkan Wars, he enlisted in the Greek Army as a sergeant, and was...

. EDES was limited in operations to Epirus

Epirus (region)

Epirus is a geographical and historical region in southeastern Europe, shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay of Vlorë in the north to the Ambracian Gulf in the south...

, and EKKA operated in a small area in Central Greece. The Italian capitulation

Armistice with Italy

The Armistice with Italy was an armistice signed on September 3 and publicly declared on September 8, 1943, during World War II, between Italy and the Allied armed forces, who were then occupying the southern end of the country, entailing the capitulation of Italy...

in September 1943 provided a windfall for the Resistance, as the Italian Army in many places simply disintegrated. Most Italian troops were swiftly disarmed and interned by the Germans, but in many places significant amounts of weaponry and equipment, as well as men, fell into the hands of the Resistance. The most spectacular case was that of the Pinerolo division and the Aosta Cavalry Regiment, which went completely over to the EAMite andartes.

The Germans now took over the Italian zone, and soon proved to be a totally different opponent from the demoralized, war-weary and far less brutal Italians. Already since the early summer of 1943, German troops had been pouring into Greece, fearing an Allied landing there (in fact falling victims to a grand-scale Allied strategic deception operation, "Operation Barclay

Operation Barclay

Operation Barclay was an Allied deception plan in support of the invasion of Sicily, in 1943, during World War II.This operation was intended to deceive the Axis military commands as to the location of the expected Allied assault across the Mediterranean and divert attention and resources from Sicily...

"). Soon they became involved in wide-ranging counterguerrilla

Counter-insurgency

A counter-insurgency or counterinsurgency involves actions taken by the recognized government of a nation to contain or quell an insurgency taken up against it...

operations, which they carried out with great ruthlessness, based on their experiences in Yugoslavia. In the course of these operations, mass reprisal

Reprisal

In international law, a reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Reprisals in the laws of war are extremely limited, as they commonly breached the rights of civilians, an action outlawed by the Geneva...

s were carried out, resulting in war crimes such as at Kommeno

Kommeno

Kommeno is a village and a former community in the Arta peripheral unit, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Nikolaos Skoufas, of which it is a municipal unit. Population 835 . During the Axis Occupation of Greece in World War II, the village was...

on August 16, the Massacre of Kalavryta

Massacre of Kalavryta

The Holocaust of Kalavryta , or the Massacre of Kalavryta , refers to the extermination of the male population and the subsequent total destruction of the town of Kalavryta, in Greece, by German occupying forces during World War II on 13 December 1943...

in December and the Massacre of Distomo in June 1944. At the same time, hundreds of villages were systematically torched and almost one million people left homeless.

Prelude to Civil War: the first conflicts

Despite the signing of an agreement in May 1943 between the three main Resistance groups (EAM/ELAS, EDES and EKKA) to cooperate and to subject themselves to the Allied Middle East High Command under General Wilson (the "National Bands Agreement"), in the political field, the mutual mistrust between EAM and the other groups escalated. EAM-ELAS was by now the dominant political and military force in Greece, and EDES and EKKA, along with the British and the Greek government-in-exile, feared that after the inevitable German withdrawal, it would try to dominate the country and establish a soviet regime. This prospect was not only linked with the increasing distrust shown by many conservative and traditional liberal members of the Greek society towards the Communists and EAM, but also with British. The British were opposed to an EAM's after-war dominance in Greece due to their political opposition to communist expansion, while on the logic of the spheres of influence they believed that such a development would lead the country, which traditionally considered belongs in their sphere of influence, to that of the Soviet Union. Finally the conflict of interests between them and the USSR settled after British secured Soviet assent to this in the so-called "percentages agreementPercentages agreement

The percentages agreement was an alleged agreement between Soviet premier Joseph Stalin and British prime minister Winston Churchill about how to divide southeastern Europe into spheres of influence during the Fourth Moscow Conference, in 1944 . This agreement was made public by Churchill...

" between Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

in October 1944. EAM on its part considered itself "the only true resistance group". Its leadership was intensely distrustful of British policies for Greece, and viewed Zervas' contacts with London and the Greek government with suspicion.

At the same time, EAM found itself under attack by the Germans and their collaborators. Dominated by the old political class, and looking already to the oncoming post-Liberation era, the new Ioannis Rallis

Ioannis Rallis

Ioannis Rallis was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 October 1944, succeeding Konstantinos Logothetopoulos in the Nazi-controlled Greek puppet government in Athens.- Early...

government had established the notorious Security Battalions

Security Battalions

The Security Battalions were Greek collaborationist military groups, formed during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II in order to support the German occupation troops.- History :...

, with the blessing of the German authorities, in order to fight exclusively against ELAS. Other anti-communist resistance groups, such as the royalist Organization "X"

Organization of National Resistance of the Interior X (Chi)

The Organization of National Resistance of the Interior X , commonly known as Organization X or simply X , was a resistance group formed during the Axis occupation of Greece, in June 1941...

, were also reinforced, receiving arms and funding by the British.

A virtual civil war was now being waged under the eyes of the Germans. In October 1943, ELAS attacked EDES in Epirus

Epirus (region)

Epirus is a geographical and historical region in southeastern Europe, shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay of Vlorë in the north to the Ambracian Gulf in the south...

, where the latter organization was the dominant resistance group, by transferring units from the neighbouring regions. This conflict continued until February 1944, when the British mission in Greece succeeded in negotiating a ceasefire (the Plaka agreement) which in the event proved to be only temporary. The attack led to an unofficial truce between EDES and the German forces in Epirus under General Hubert Lanz

Hubert Lanz

Karl Hubert Lanz was a German Army officer who rose to the rank of General der Gebirgstruppe during the Second World War, in which he led units in the Eastern Front and in the Balkans. After the war, he was tried and convicted for several atrocities committed by units under his command in the...

. But the fight continued amongst ELAS and the other minor resistance groups (like "X"), as well as against the Security Battalions, even in the streets of Athens, until the German withdrawal in October 1944. In March, EAM established its own rival government in Free Greece, the Political Committee of National Liberation

Political Committee of National Liberation

The Political Committee of National Liberation , commonly known as the "Mountain Government" was a communist-dominated government established in Greece in 1944 in opposition to both the collaborationist German-controlled government at Athens and to the royal government-in-exile in Cairo...

, clearly staking its claim to a dominant role in post-war Greece. Consequently, on Easter Monday, 17 April 1944, ELAS forces attacked and destroyed the EKKA's 5/42 Regiment, capturing and executing many of its men, including its leader Colonel Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros

Dimitrios Psarros was a Greek army officer and resistance leader. He was the founder and leader of the resistance group National and Social Liberation , the third-most significant organization of the Greek Resistance movement after the National Liberation Front and the National Republican Greek...

. The event caused a major shock in the Greek political scene, since Psarros was a well-known republican, patriot and anti-royalist. For EAM-ELAS, this act was fatal, as it strengthened suspicion of its intentions for the post-Occupation period, and drove many liberals and moderates, especially in the cities, against it, cementing the emerging rift in Greek society between pro- and anti-EAM segments.

Resistance in the islands and Crete

Patrick Leigh Fermor

Sir Patrick "Paddy" Michael Leigh Fermor, DSO, OBE was a British author, scholar and soldier, who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during World War II. He was widely regarded as "Britain's greatest living travel writer", with books including his classic A Time of...

and George Psychoundakis

George Psychoundakis

George Psychoundakis was a Greek Resistance fighter on Crete during the Second World War. He was a shepherd, a war hero and an author. He served as dispatch runner between Petro Petrakas and Papadakis behind the German lines for the Cretan resistance Movement and later, from 1941 to 1945, for the...

. Resistance operations included the abduction

Kidnap of General Kreipe

The Kidnap of General Kreipe was a Second World War operation by the Special Operations Executive, an organisation of the United Kingdom. The mission took place on the German occupied island of Crete in May 1944....

of General Heinrich Kreipe

Heinrich Kreipe

Karl Heinrich Georg Ferdinand Kreipe was a German general, who served in World War II. He is most famous for his spectacular abduction by British and Cretan resistance fighters from occupied Crete in April 1944....

by Patrick Leigh Fermor

Patrick Leigh Fermor

Sir Patrick "Paddy" Michael Leigh Fermor, DSO, OBE was a British author, scholar and soldier, who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during World War II. He was widely regarded as "Britain's greatest living travel writer", with books including his classic A Time of...

and Bill Stanley Moss

W. Stanley Moss

Ivan William "Billy" Stanley Moss MC , was a British army officer in World War II, and later a successful writer, broadcaster, journalist and traveller. He served with the Coldstream Guards and the Special Operations Executive . He was a best-selling author in the 1950s, based both on his novels...

and the battle of Trahili.

Resistance in the cities

Resistance in the cities was organized quickly, but of necessity groups were small and fragmented. The cities, and the working-class suburbs of Athens in particular, witnessed appalling suffering in the winter of 1941-42, when food confiscations and disrupted communications caused widespread famine and perhaps hundreds of thousands of deaths. This caused fertile ground for recruitment, but lack of equipment, funds and organization limited the spread of the resistance. The main roles of resistance operatives were intelligence and sabotage, mostly in cooperation with British Intelligence. One of the earliest jobs of the urban resistance was helping stranded Commonwealth soldiers escape. The resistance groups stayed in touch with British handlers through wireless sets, met and helped British spies and saboteurs that parachuted in, provided intelligence, conducted propaganda efforts, and ran escape networks for allied operatives and Greek young men wishing to join the Hellenic forces in exile. Wireless equipment, money, weapons and other support was mainly supplied by British Intelligence, but it was never enough. Fragmentation of groups, the need for secrecy, and emerging conflicts between right and left, monarchists and republicans, did not help. Urban resistance work was very dangerous: operatives were always in danger of arrest and summary execution, and suffered heavy casualties. Captured fighters were routinely tortured by the AbwehrAbwehr

The Abwehr was a German military intelligence organisation from 1921 to 1944. The term Abwehr was used as a concession to Allied demands that Germany's post-World War I intelligence activities be for "defensive" purposes only...

and the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

, and confessions used to roll up networks. The job of wireless operators was perhaps the most dangerous, since the Germans used direction-finding equipment to pinpoint the location of transmitters; operators were often shot on the spot, and those were the lucky ones, since immediate execution prevented torture.

Urban protest

One of the most important forms of resistance were the mass protest movements. The first such event occurred during the national anniversary of 25 March 1942, when students attempted to lay a wreath at the Monument of the Unknown Soldier. This resulted in clashes with mounted CarabinieriCarabinieri

The Carabinieri is the national gendarmerie of Italy, policing both military and civilian populations, and is a branch of the armed forces.-Early history:...

, and marked the awakening of the spirit of Resistance amongst the wider urban population. Soon after, from 12–14 April, the "TTT" (Telecommunications & Postal) workers began a strike in Athens, which spread throughout the country. Initially, the strikers' demands were financial, but it quickly assumed a political aspect, as the strike was encouraged by EAM's labour union organization, EEAM. Finally, the strike ended on April 21, with the full capitulation of the collaborationist government to the strikers' demands, including the immediate release of arrested strike leaders.

In early 1943, rumours spread of a planned mobilization of the labour force by the occupation authorities, with the intent of sending them to work in Germany

Arbeitseinsatz

Arbeitseinsatz was forced labour during World War II when German men were called up for military service and German authorities rounded up labourers, some from Germany but more from the occupied territories, to fill in the vacancies...

. The first reactions began amongst students on 7 February, but soon grew in scope and volume. Throughout February, successive strikes and demonstrations paralyzed Athens, culminating in a massive rally on the 24th. The tense climate was amply displayed at the funeral of Greece's national poet, Kostis Palamas

Kostis Palamas

Kostis Palamas was a Greek poet who wrote the words to the Olympic Hymn. He was a central figure of the Greek literary generation of the 1880s and one of the cofounders of the so-called New Athenian School along with Georgios Drosinis, Nikos Kampas, Ioanis Polemis.-Biography:Born in Patras, he...

, on 28 February, which turned into an anti-Axis demonstration.

Risks involved

Resisting the Axis occupation was fraught with risks. Foremost among these for the partisans was death in combat as the German military forces were far superior. However, the guerrilla fighters also had to face starvation, brutal environmental conditions in the mountains of Greece, while poorly clothed and shod.The resistance also involved risks for ordinary Greeks. Attacks often incited reprisal

Reprisal

In international law, a reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Reprisals in the laws of war are extremely limited, as they commonly breached the rights of civilians, an action outlawed by the Geneva...

killings of civilians by the German occupying forces. Villages were burned and its inhabitants massacred. The Germans also resorted to hostage taking. There were also accusations that many of ELAS' attacks against German soldiers didn't happen for resistance reasons but aiming the destuction of specific villages and the recruitment of their men. Quotas were even introduced determining the number of civilians or hostages to be killed in response to the death or wounding of German soldiers.

Table of main resistance groups

| Group name | Political orientation | Political leadership | Military arm | Military leadership | Estimated peak membership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Liberation Front (Ethnikó Apeleftherotikó Métopo/ΕΑΜ) |

Broad leftist front affiliated with the Communist Party of Greece | Georgios Siantos | Greek People's Liberation Army (Ellinikós Laikós Apeleftherotikós Stratós/ELAS) | Aris Velouchiotis Aris Velouchiotis Aris Velouchiotis , the nom de guerre of Athanasios Klaras , was the most prominent leader and chief instigator of the Greek People's Liberation Army , the military branch of the National Liberation Front , which was the major resistance organization in occupied Greece from 1942 to 1945... , Stefanos Sarafis Stefanos Sarafis Stefanos Sarafis was an officer of the Hellenic Army who played an important role during the Greek Resistance.- Early life and career :Sarafis was born at Trikala in 1890, and studied law in the University of Athens. During the Balkan Wars, he enlisted in the Greek Army as a sergeant, and was... |

50,000 + 30,000 reserves (October 1944) |

| National Republican Greek League (Ethnikós Dimokratikós Ellinikós Sýndesmos/EDES) |

Venizelist Venizelism Venizelism was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid 1970s.- Ideology :Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:*Opposition to Monarchy... , nationalist Greek nationalism Greek nationalism has its roots in the rise of nationalism in Europe in the 19th century, and was characterised by the struggle for independence against the Ottoman Empire, culminating in the Greek War of Independence , assisted by philhellenes such as Lord Byron.After independence was achieved,... , republican Republicanism Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context... , socialist Socialism Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,... , anti-communist Anti-communism Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:... |

Nikolaos Plastiras Nikolaos Plastiras Nikolaos Plastiras was a Greek general and politician, who served thrice as Prime Minister of Greece. A distinguished soldier and known for his personal bravery, he was known as "O Mavros Kavalaris" during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922... (nominal), Komninos Pyromaglou Komninos Pyromaglou Komninos Pyromaglou , was a Greek teacher and politician, and one of the driving forces behind the foundation of the National Republican Greek League , the second-largest Resistance organization in Axis-occupied Greece during World War II... |

National Groups of Greek Guerrillas (Ethnikés Omádes Ellínon Antartón/EOEA) |

Napoleon Zervas Napoleon Zervas Napoleon Zervas was a Greek general and resistance leader during World War II. He organized and led the National Republican Greek League , the second most significant , in terms of size and activity, resistance organization against the Axis Occupation of Greece.-Early life and army career:Zervas... |

12,000 + ca. 5,000 reserves (October 1944) |

| National and Social Liberation (Ethnikí Kai Koinonikí Apelefthérosis/EKKA) |

Venizelist Venizelism Venizelism was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid 1970s.- Ideology :Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:*Opposition to Monarchy... , republican Republicanism Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context... , liberal Liberalism Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,... , anti-communist Anti-communism Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:... |

Georgios Kartalis Georgios Kartalis - Early life and political career :Kartalis was born in Athens to a distinguished family from Volos. He went to school in Geneva and enrolled in the ETH Zürich, only to change after the first year to Economics at the University of Munich and the University of Leipzig... |

5/42 Evzone Regiment (5/42 Sýntagma Evzónon) |

Dimitrios Psarros Dimitrios Psarros Dimitrios Psarros was a Greek army officer and resistance leader. He was the founder and leader of the resistance group National and Social Liberation , the third-most significant organization of the Greek Resistance movement after the National Liberation Front and the National Republican Greek... and Evripidis Bakirtzis |

1,000 (spring 1943) |

Notable Resistance members

EAM/ELAS and affiliated:

|

EDES:

EKKA:

|

Other:

|

British agents Office of Strategic Services The Office of Strategic Services was a United States intelligence agency formed during World War II. It was the wartime intelligence agency, and it was a predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency... :

|

See also

- June 1942 Crete airfield raidsJune 1942 Crete airfield raidsOperation Albumen was the name given to British Commando raids in June 1942, on German airfields in the Axis-occupied Greek island of Crete, to prevent them from being used for supporting the Afrika Korps in the Western Desert Campaign in World War II...

- French ResistanceFrench ResistanceThe French Resistance is the name used to denote the collection of French resistance movements that fought against the Nazi German occupation of France and against the collaborationist Vichy régime during World War II...

- Armia KrajowaArmia KrajowaThe Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

- Partisans (Yugoslavia)Partisans (Yugoslavia)The Yugoslav Partisans, or simply the Partisans were a Communist-led World War II anti-fascist resistance movement in Yugoslavia...

Sources

- R. Capell, Simiomata: A Greek Note Book 1944-45, London 1946

- N.G.L. Hammond, Venture into Greece: With the Guerillas, 1943-44, London, 1983. (Like Woodhouse, he was a member of the British Military Mission)

- Reginald Leeper, When Greek Meets Greek: On the War in Greece, 1943-1945

- United States Army Center of Military History, German Antiguerrilla Operations in The Balkans (1941-1944) Washington DC: United States ArmyUnited States ArmyThe United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

. - Hondros, John L. (1983), Occupation and Resistance: The Greek Agony, New York: Pella Publishing

External links

- Martyr Cities & Villages of Greece Network 1940-1945 (in Greek)

- Andartikos - a short history of the Greek Resistance, 1941-5 on libcom.org/history

- Official site of the documentary film The 11th Day which contains an extensive interview with Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, and documents the Battle of Trahili, filmed in 2003.