Battle of Greece

Encyclopedia

The Battle of Greece is the common name for the invasion and conquest of Greece

by Nazi Germany

in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth

forces, while the Germans' Axis

allies Italy and Bulgaria

played secondary roles. The Battle of Greece is usually distinguished from the Greco-Italian War

fought in northwestern Greece and southern Albania

from October 1940, as well as from the Battle of Crete

fought in late May. These operations, along with the Invasion of Yugoslavia

, comprise the Balkans Campaign of World War II

.

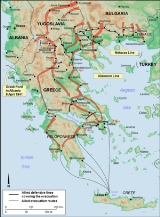

The Balkans Campaign began with the Italian invasion of Greece on 28 October 1940. Within weeks, the Italians were driven out of Greece and Greek forces pushed on to occupy much of southern Albania. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack failed, and Germany was forced to come to the aid of its ally. Operation Marita began on 6 April 1941, with German troops invading Greece through Bulgaria in an effort to secure its southern flank. The combined Greek and British Commonwealth forces fought back with great tenacity, but were vastly outnumbered and out-gunned, and finally collapsed. Athens

fell on 27 April, however the British managed to evacuate about 50,000 troops. The Greek campaign ended in a quick and complete German victory with the fall of Kalamata

in the Peloponnese

; it was over within 24 days. The conquest of Greece was completed through the capture of Crete a month later. Greece remained under occupation by the Axis powers until October 1944.

Some historians regard the German campaign in Greece as decisive in determining the course of World War II, maintaining that it fatally delayed the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union

. Others hold that the campaign had no influence on the launching of Operation Barbarossa

as monsoon conditions in the Ukraine

would have postponed Axis operations regardless. Others believed British intervention in Greece as a hopeless undertaking, a "political and sentimental decision" or even a "definite strategic blunder." It has also been suggested the British strategy was to create a barrier in Greece, to protect Turkey

, the only (neutral) country standing between an Axis block in the Balkans and the oil-rich Middle East

.

—the Prime Minister of Greece

—sought to maintain a position of neutrality

. However, Greece was increasingly subject to pressure from Italy, which culminated in the Italian submarine Delfinos torpedoing of the Greek cruiser on 15 August 1940. Italian leader Benito Mussolini

was irritated that Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

had not consulted him on his war policy, and wished to establish his independence. He hoped to match the military success of the Germans through a victorious attack on Greece, a country he regarded as an easy opponent.* Goldstein (1992), 53 On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision to invade Greece. In the early hours of 28 October, Italian Ambassador Emmanuel Grazzi presented Metaxas with a three-hour ultimatum, in which he demanded free passage for troops to occupy unspecified "strategic sites" within Greek territory. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum (the refusal is commemorated as Ohi Day, a national holiday in Greece), but even before its expiration, Italian troops had invaded Greece through Albania. The principal Italian thrust was directed towards Epirus, but made little progress. During the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas the Italians fought their way across the Thyamis (Kalamas) river, but were then forced to a halt. Within three weeks, a successful Greek counterattack was underway. A number of towns in southern Albania fell to Greek forces, and neither a change in Italian commanders, nor the arrival of a substantial number of reinforcements had much effect.

After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched a large-scale counterattack across the centre of the front on 9 March 1941, which, despite the superiority of the Italian armed forces, failed. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the counterattack, and then left Albania 12 days later.* More U-boat Aces Hunted down, OnWar.Com Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated meagre military resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather and launched an attack without the advantage of surprise and without the support of the Bulgarians.* Rodogno (2006), 29–30 Even elementary precautions, such as the issue of winter clothing had not been taken. Nor had Mussolini taken into consideration the recommendations of the Italian Commission of War Production, which had warned that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of continuous warfare until 1949.

During the six month fight against Italy, the Greek army made local gains by eliminating enemy salient

s. Nevertheless, Greece did not have a substantial armaments industry, and both its equipment and ammunition supplies increasingly relied on stocks captured by British forces from defeated Italian armies in North Africa

. In order to man the battlefront in Albania, the Greek command was forced to make withdrawals from Eastern Macedonia

and Western Thrace

. Anticipation of a German attack expedited the need to reverse the position; the available forces were proving unable to sustain resistance on both fronts. The Greek command decided to support its success in Albania, regardless of how the situation might develop under the impact of a German attack from the Bulgarian border.

and Lemnos

. The Führer

ordered his Army General Staff to prepare for an invasion of Northern Greece via Romania

and Bulgaria. His plans for this campaign were incorporated into a master plan aimed at depriving the British of their Mediterranean bases.* On 12 November, the German Armed Forces High Command

issued Directive No. 18, in which they scheduled simultaneous operations against Gibraltar

and Greece for the following January. However, in December 1940, German ambition in the Mediterranean underwent considerable revision when Spain's General Francisco Franco

rejected plans for an attack on Gibraltar. Consequently, Germany's offensive in Southern Europe

was restricted to the campaign against Greece. The Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940. The document outlined the Greek campaign under the code designation "Operation Marita", and planned for German occupation of the northern coast of the Aegean Sea

by March 1941. It also planned for the seizure of the entire Greek mainland, if that became necessary.*

* Svolopoulos (1997), 288 During a hastily called meeting of Hitler's staff after the unexpected 27 March coup d'état

against the Yugoslav government, orders for the future campaign in Yugoslavia

were drafted, as well as changes to the plan for the attack on Greece. On 6 April, both Greece and Yugoslavia were to be attacked.* McClymont, 158–159

Britain

Britain

was obliged to assist Greece by the declaration of 1939, which stated that in the event of a threat to Greek or Romanian independence, "His Majesty's Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Greek or Romanian Government [...] all the support in their power." The first British effort was the deployment of Royal Air Force

squadrons commanded by Air Commodore

John d'Albiac

, which were sent in November 1940. With the consent of the Greek government, British forces were dispatched to Crete on 31 October to guard Suda Bay, enabling the Greek government to redeploy the 5th Cretan Division

to the mainland.

On 17 November 1940, Metaxas proposed to the British government the undertaking of a joint offensive in the Balkans with the Greek strongholds in southern Albania as the base of the operations. The British were reluctant to discuss Metaxas' proposal, because the deployment of troops necessary for implementing the Greek plan would seriously endanger the Commonwealth military operations in North Africa. During a meeting of British and Greek military and political leaders in Athens on 13 January 1941, General

Alexandros Papagos—Commander-in-Chief

of the Hellenic Army

—asked Britain for nine fully equipped divisions and corresponding air support. The British responded that, because of their commitment to the fight in North Africa, all they could offer was the immediate dispatch of a small token force of less than divisional strength. This offer was rejected by the Greeks who feared that the arrival of such a contingent would precipitate a German attack without giving them any sizable assistance. British help would be requested if and when German troops crossed the Danube from Romania into Bulgaria.* Blau (1953), 71–72

, and instructed Anthony Eden

and Sir John Dill

to resume negotiations with the Greek government. A meeting attended by Eden and the Greek leadership, including King George II

, Prime Minister Alexandros Koryzis—the successor of Metaxas, who had died on 29 January 1941—and Papagos took place in Athens on 22 February. There the decision to send a British Commonwealth expeditionary force was made. German troops had been massing in Romania and on 1 March 1941, Wehrmacht

forces began to move into Bulgaria. At the same time, the Bulgarian Army mobilised and took up positions along the Greek frontier.

On 2 March, Operation Lustre

—the transportation of troops and equipment to Greece—began and 26 troopship

s arrived at the port of Piraeus

. On 3 April, during a meeting of British, Yugoslav, and Greek military representatives, the Yugoslavs promised to block the Strymon valley

in case of a German attack across their territory. During this meeting, Papagos laid stress on the importance of a joint Greco-Yugoslavian offensive against the Italians, as soon as the Germans launched their offensive against the two countries. Until 24 April, more than 62,000 Commonwealth troops (British, Australians, New Zealanders, Palestinians and Cypriots

), were sent to Greece, comprising the 6th Australian Division, the New Zealand 2nd Division

, and the British 1st Armoured Brigade

. The three formations later became known as 'W' Force, after their commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. Air Commodore Sir John D'Albiac commanded the British air forces in Greece.

, which possessed few river valleys or passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion courses were located west of Kyustendil

; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Strimon valley to the south. Greek border fortifications had been adapted for the terrain, and a formidable defence system covered the few available roads. The Strimon and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier, and both of their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line

. This system of concrete pillboxes and field fortifications was constructed along the Bulgarian border in the late 1930s, and was based on principles similar to those applied to the Maginot Line

. Its strength resided mainly in the inaccessibility of the intermediate terrain leading up to the defence positions.* Blau (1953), 75

The mountainous terrain of Greece favored a defensive strategy, and the high ranges of the Rhodope

The mountainous terrain of Greece favored a defensive strategy, and the high ranges of the Rhodope

, Epirus

, Pindus

, and Olympus

mountains offered many opportunities to stop an invader. However, adequate air power was required to prevent defending ground forces from becoming trapped in the many defile

s. Although an invading force from Albania

could be stopped by a relatively small number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, the northeastern part of the country was difficult to defend against an attack from the north.

Following a conference in Athens that March, the British command believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon

Line—a short front facing northeastward along the Vermion Mountains

, and the lower Haliacmon

river. Papagos awaited clarification from the Yugoslav government, and later proposed to hold the Metaxas Line

—by then a symbol of national security to the Greek populace—and not withdraw any of his divisions from Albania.* Papagos (1949), 115

* Ziemke, Balkan Campaigns He argued that to do so would be seen as a concession of victory to the Italians. The strategically important port of Thessaloniki

lay practically indefensible, and transportation of British troops to the city remained dangerous. Papagos proposed to take advantage of the area's difficult terrain and prepare fortifications, while at the same time protecting Thessaloniki.

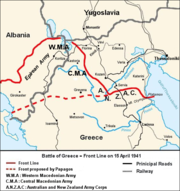

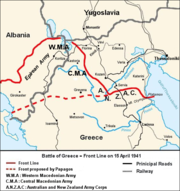

General Dill described Papagos' attitude as "unaccommodating and defeatist", and argued that his plan disregarded the fact that Greek troops and artillery were capable of only token resistance. The British believed that the Greek rivalry with Bulgaria—the Metaxas Line was designed specifically for use in the event of war with Bulgaria—as well as their traditionally good terms with the Yugoslavs, left their north-western border largely undefended. Despite their concerns over the vulnerability of the border system, and their awareness that it was likely to collapse in the event of a German thrust from the Strimon and Axios rivers, the British eventually conceded to the Greek command. On 4 March, Dill accepted the plans for the Metaxas line, and on 7 March, agreement was ratified by the British Cabinet.* McClymont (1959), 107–108 The overall command was to be retained by Papagos, and the Greek and British commands resigned themselves to fighting a delaying action in the northeastern part of the country. Nevertheless, the British did not move their troops, because General Wilson regarded them as too weak to maintain such a broad front line. Instead, he took a position some 40 mi (64.4 km) west of the Axios, across the Haliacmon Line.* Ziemke, Balkan Campaigns The two main objectives in establishing this position were to maintain contact with the Greek army in Albania, and to deny German access to Central Greece. This had the advantage of requiring a smaller force than other options, while still allowing more time for preparation. However, it meant abandoning nearly the whole of Northern Greece, and was thus unacceptable to the Greeks for both political and psychological reasons. Moreover, the left flank of the line was susceptible to flanking from Germans operating through the Monastir gap in Yugoslavia. However, the possibility of a rapid disintegration of the Yugoslav Army, and a German thrust into the rear of the Vermion position, was not taken into consideration.

The German strategy was based on utilisation of the so-called "blitzkrieg

" methods which had proved successful during the invasions of Western Europe, and confirmed their effectiveness during the invasion of Yugoslavia

. The German command planned to couple an attack of ground troops and tanks with support from the air, and make a rapid thrust into the territory. Once Thessaloniki was captured, Athens and the port of Piraeus

would be the next principal targets. With Piraeus and the Isthmus of Corinth

in German hands, the withdrawal and evacuation of British and Greek forces would be fatally compromised.

The Fifth Yugoslav Army was given responsibility for the defence of the southeastern border between Kriva Palanka

The Fifth Yugoslav Army was given responsibility for the defence of the southeastern border between Kriva Palanka

and the Greek border. At the time of the German attack, the Yugoslav troops were not yet fully mobilised, they also lacked a sufficient amount of modern equipment or weapons to be fully effective. Following the entry of German forces into Bulgaria, the majority of Greek troops were evacuated from Western Thrace

. By this time, the total strength of the Greek forces defending the Bulgarian border totaled roughly 70,000 men (sometimes grouped as the "Greek Second Army" in English and German sources, although no such formation existed). The remainder of the Greek forces—14 divisions (often erroneously referred to as the "Greek First Army" by foreign sources)—was committed in Albania.

On 28 March, the Greek forces in Central Macedonia—the 12th and 20th Infantry Divisions—were put under the command of General Wilson, who established his headquarters northwest of Larissa

. The New Zealand division took a position north of Mount Olympus, while the Australian division blocked the Haliacmon valley up to the Vermion range. The Royal Air Force continued to operate from airfields in Central and Southern Greece; however, few planes could be diverted to the theater. The British forces were near to fully motorised, but their equipment was more suited to desert warfare than to the steep mountain roads of Greece. There was a shortage of tanks and anti-aircraft gun

s, and the lines of communication across the Mediterranean were vulnerable, because each convoy had to pass close to enemy-held islands in the Aegean; despite the fact that the British Royal Navy dominated the Aegean Sea

. These logistical

problems were aggravated by the limited availability of shipping and capacity of the Greek ports.

The German Twelfth Army

—under the command of Field Marshal

Wilhelm List—was charged with the execution of Operation Marita. His army was composed of six units:

. Their strategy was to create a diversion through the campaign in Albania, thus stripping the Greek Army of sufficient manpower for the defence of their Yugoslavian and Bulgarian borders. By driving armoured wedges through the weakest links of the defence chain, the ability to penetrate into enemy territory would be more easily achieved, and would not necessitate the maneuver of their armour behind an infantry advance. Once the weak defence systems of Southern Yugoslavia were overrun by German armour, the Metaxas Line could be outflanked by highly mobile forces thrusting southward from Yugoslavia. Thus possession of Monastir and the Axios valley leading to Thessaloniki became essential for such an outflanking maneuver.

The Yugoslav coup d'état led to a sudden change in the plan of attack, and confronted the Twelfth Army with a number of difficult problems. According to the 28 March Directive No. 25, the Twelfth Army was to regroup its forces in such a manner that a mobile task force would be available to attack via Niš

toward Belgrade

. With only nine days left before their final deployment, every hour became valuable, and each fresh assembly of troops would need time to mobilise. By the evening of 5 April, each attack force intended to enter either southern Yugoslavia or Greece had been assembled.

At dawn on 6 April, the German armies invaded Greece, while the Luftwaffe

At dawn on 6 April, the German armies invaded Greece, while the Luftwaffe

began an intensive bombardment of Belgrade

. The XL Panzer Corps—which had been intended for use in an attack across southern Yugoslavia—began their assault at 05:30. They also made thrusts across the Bulgarian frontier at two separate points. By the evening of 8 April, the 73rd Infantry Division captured Prilep

, severing an important rail line between Belgrade and Thessaloniki and isolating Yugoslavia from its allies. The Germans were now in possession of terrain which was favorable to the continuation of the offensive. On the evening of 9 April, General Stumme deployed his forces north of Monastir, in preparation for the extension of the attack across the Greek border toward Florina

. This position threatened to encircle the Greeks in Albania and W Force in the area of Florina, Edessa

, and Katerini

. While weak security detachments covered the rear of his corps against a surprise attack from central Yugoslavia, elements of the 9th Panzerdivision drove westward to link up with the Italians at the Albanian border.

The 2nd Panzerdivision

(XVIII Mountain Corps) entered Yugoslavia from the east on the morning of 6 April, and advanced westward through the Struma Valley. It encountered little enemy resistance, but was delayed by road clearance demolitions, mine

s, and muddy roads. Nevertheless, the division was able to reach the objective of the day, the town of Strumica

. On 7 April, a Yugoslav counter attack against the northern flank of the division was repelled, and the following day the division forced its way across the mountains and overran the Greek 19th Motorised Infantry Division Units stationed south of Doiran

lake. Despite many delays along the narrow mountain roads, an armoured advance guard dispatched in the direction of Thessaloniki succeeded in entering the city by the morning of April 9. Thessaloniki's capture took place without a struggle, and was followed by the surrender of the Greek East Macedonia Army Section, taking effect at 13:00 on 10 April.

, which comprised the 7th, 14th and 18th Infantry Divisions under the command of Lieutenant General Konstantinos Bakopoulos

. The line ran for about 170 km (105.6 mi) along the river Nestos to the east, and then further to the east following the Bulgarian border as far as Mount Beles

near the Yugoslav border. The fortifications were designed to garrison an army of over 200,000 troops, but due to a lack of available manpower, the actual number was roughly 70,000. As a result of the low numbers, the line's defences were thinly spread.

The initial German attacks against the line were undertaken by a single German infantry unit reinforced by two mountain divisions of the XVIII Mountain Corps. These first forces encountered strong resistance, and had limited success.* Blau (1953), 88 A German report at the end of the first day described how the German 5th Mountain Division

"was repulsed in the Rupel Pass despite strongest air support and sustained considerable casualties". Of the 24 forts which made up the Metaxas Line, only two had fallen, and then only after they had been destroyed. Most fortresses—including Rupel, Echinos

, Arpalouki, Paliouriones, Perithori, Karadag, Lisse and Istibey—resisted for three days.

The line was penetrated following a three-day struggle during which the Germans pummeled the forts with artillery

and dive bomber

s. The main credit for this achievement must be given to the 6th Mountain Division, which crossed a 7000 ft (2,133.6 m) snow-covered mountain range and broke through at a point that had been considered inaccessible by the Greeks. The force reached the rail line to Thessaloniki on the evening of 7 April. The other XVIII Mountain Corps units advanced step by step under great hardship. The 5th Division, together with the reinforced 125th Infantry Regiment, penetrated the Strimon defences on 7 April and attacked along both banks of the river, clearing one bunker after another as they passed. Nevertheless the unit suffered heavy casualties, to the extent that it was withdrawn from further action after it had reached its objective location. The 72nd Infantry Division advanced from Nevrokop

across the mountains, and although it was handicapped by a shortage of pack animals, medium artillery, and mountain equipment, managed to break through the Metaxas Line on the evening of 9 April, when it reached the area northeast of Serres

. Even after General Bakopoulos surrendered the Metaxas Line, isolated fortresses held out for days, and were not taken until heavy artillery was used against them. Some field troops and soldiers manning the frontier continued to fight on, as a result a number were able to evacuate by sea.

. The 50th Infantry Division advanced far beyond Komotini

towards the Nestos river, which both divisions reached on the next day. On 9 April, the Greek forces defending the Metaxas Line capitulated unconditionally following the collapse of Greek resistance east of the Axios river. In an 9 April estimate of the situation, Field Marshal List expressed the opinion that as a result of the swift advance of the mobile units, his 12th Army was now in a favorable position to gain access to central Greece by breaking the enemy buildup behind the Axios river. On the basis of this estimate, List requested the transfer of the 5th Panzer Division from First Panzer Group to the XL Panzer Corps. He reasoned that its presence would give additional punch to the German thrust through the Monastir gap. For the continuation of the campaign, he formed two attack groups, an eastern one under the command of XVIII Mountain Corps, and a western group led by XL Panzer Corps.

. Against all expectations, the Monastir gap had been left open, and the Germans exploited their chance. First contact with Allied troops was made north of Vevi

at 11:00 on 10 April. SS troops seized Vevi

on 11 April, but were stopped at the Klidi Pass just south of the town, where a mixed Commonwealth-Greek formation—known as Mackay

Force—was assembled to, as Wilson put it, "....stop a blitzkrieg down the Florina valley." During the next day, the SS regiment reconnoitered the enemy positions, and at dusk launched a frontal attack against the pass. Following heavy fighting, the Germans overcame the enemy resistance, and broke through the defence. By the morning of 14 April, the spearheads of the 9th Panzer Division reached Kozani.

. On 14 April, the 9th Panzerdivision established a bridgehead across the Haliacmon river, but an attempt to advance beyond this point was stopped by intense enemy fire. This defence had three main components: the Platamon

tunnel area between Olympus and the sea, the Olympus pass itself, and the Servia pass to the southeast. By channelling the attack through these three defiles, the new line offered far greater defensive strength for the limited forces available. The defences of the Olympus and Servia passes consisted of the 4th New Zealand Brigade, 5th New Zealand Brigade, and the 16th Australian Brigade. For the next three days, the advance of the 9th Panzer Division was stalled in front of these resolutely held positions.

A ruined castle dominated the ridge across which the coastal pass led to Platamon. During the night of 15 April, a German motorcycle battalion supported by a tank battalion attacked the ridge, but the Germans were repulsed by the 21st New Zealand Battalion

under Colonel Macky, which suffered heavy losses in the process. Later that day a German armoured regiment arrived and struck the coastal and inland flanks of the battalion, but the New Zealanders held their ground. After being reinforced during the night of the 15th-16th, the Germans managed to assemble a tank battalion, an infantry battalion, and a motorcycle battalion. The German infantry attacked the New Zealanders' left company at dawn, while the tanks attacked along the coast several hours later.

The New Zealand battalion withdrew, crossed the Pineios

The New Zealand battalion withdrew, crossed the Pineios

river; by dusk, they had reached the western exit of the Pineios Gorge, suffering only light casualties. Macky was informed that it was "essential to deny the gorge to the enemy until April 19 even if it meant extinction". He sank a crossing barge at the western end of the gorge once all his men were across and began to set up defences. The 21st battalion was reinforced by the Australian 2/2nd Battalion

and later by the 2/3rd

, this force became known as "Allen force" after Brigadier "Tubby" Allen

. The 2/5th

and 2/11th battalions

moved to the Elatia

area south-west of the gorge and were ordered to hold the western exit possibly for three or four days.

On 16 April, General Wilson met General Papagos at Lamia and informed him of his decision to withdraw to Thermopylae. General Blamey divided responsibility between generals Mackay and Freyberg

during the leapfrogging move back to Thermopylae. Mackay would protect the flanks of the New Zealand Division as far south as an east-west line through Larissa and would control the withdrawal through Domokos

to Thermopylae of the Savige

and Zarkos Forces, and finally of Lee Force; the 1st Armoured Brigade

would cover the withdrawal of Savige Force to Larissa and thereafter the withdrawal of the 6th Division under whose command it would come; Freyberg would control the withdrawal of Allen Force which was to move along the same route as the New Zealand Division. The British Commonwealth forces remained under constant attack throughout the entire withdrawal.

On the morning of 18 April, the struggle for the Pineios gorge was over, when German armoured infantry crossed the river on floats and the 6th Mountain Division troops worked their way around the New Zealand battalion, which was subsequently dispersed. On 19 April, the first XVIII Mountain Corps troops entered Larissa and took possession of the airfield, where the British had left their supply dumps intact. The seizure of ten truckloads of rations and fuel enabled the spearhead units to continue their drive without ceasing. The port of Volos

, at which the British had re-embarked numerous units during the last few days, fell on 21 April; there, the Germans captured large quantities of valuable diesel and crude oil.

As the invading Germans advanced deep into Greek territory, the Greek Army Section of Epirus (ΤΣΗ) operating in Albania was reluctant to retreat. General Wilson described this unwillingness as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians." It was not until 13 April that the first Greek elements began to withdraw toward the Pindus mountains. The Allies' retreat to Thermopylae uncovered a route across the Pindus mountains by which the Germans might flank the Greek army in a rearguard action. An elite SS formation—the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler brigade—was assigned the mission of cutting off the Greek Epirus Army's line of retreat from Albania by driving westward to the Metsovon pass, and from there to Ioannina. On 14 April, heavy fighting took place

As the invading Germans advanced deep into Greek territory, the Greek Army Section of Epirus (ΤΣΗ) operating in Albania was reluctant to retreat. General Wilson described this unwillingness as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians." It was not until 13 April that the first Greek elements began to withdraw toward the Pindus mountains. The Allies' retreat to Thermopylae uncovered a route across the Pindus mountains by which the Germans might flank the Greek army in a rearguard action. An elite SS formation—the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler brigade—was assigned the mission of cutting off the Greek Epirus Army's line of retreat from Albania by driving westward to the Metsovon pass, and from there to Ioannina. On 14 April, heavy fighting took place

at Kleisoura pass, where the Germans blocked the Greek withdrawal. The withdrawal extended across the entire Albanian front, with the Italians in hesitant pursuit.

General Papagos rushed Greek units to the Metsovon pass where the Germans were expected to attack. On 18 April, a pitched battle between several Greek units and the LSSAH brigade—which had by then reached Grevena

—erupted. The Greek units lacked the equipment necessary to fight against a motorised unit, and were soon encircled and overwhelmed. The Germans advanced further and on 19 April captured Ioannina, the final supply route of the Greek Epirus Army. Allied newspapers dubbed the Greek army's fate as a modern day Greek tragedy. Historian and former war-correspondent Christopher Buckley—when describing the fate of the Greek army—stated that "one experience[d] a genuine Aristotelian catharsis

, an awe-inspiring sense of the futility of all human effort and all human courage."

On 20 April, the commander of the Greek forces in Albania—General Georgios Tsolakoglou

—realised the hopelessness of the situation and offered to surrender his army, which then consisted of fourteen divisions. World War II historian John Keegan

writes that Tsolakoglou "was so determined [...] to deny the Italians the satisfaction of a victory they had not earned that [...] he opened [a] quite unauthorised parley with the commander of the German SS division opposite him, Sepp Dietrich

, to arrange a surrender to the Germans alone." On strict orders from Hitler negotiations were kept secret from the Italians, and the surrender was accepted. Outraged by this decision Mussolini ordered counterattacks against the Greek forces, which were repulsed. It took personal representation from Mussolini to Hitler to bring together an armistice in which Italy was included on 23 April. Greek soldiers were not treated as prisoners of war and were allowed instead to go home after the demobilisation of their units, while their officers were permitted to retain their side arms.

As early as 16 April, the German command realised that the British were evacuating troops on ships at Volos and Piraeus. The whole campaign had taken on the character of a pursuit. For the Germans, it was now primarily a question of maintaining contact with the retreating British forces, and foiling their evacuation plans. German infantry divisions were withdrawn from action due to a lack of mobility. The 2nd and 5th Panzerdivisions, the 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment and both mountain divisions launched a pursuit of the enemy forces.

As early as 16 April, the German command realised that the British were evacuating troops on ships at Volos and Piraeus. The whole campaign had taken on the character of a pursuit. For the Germans, it was now primarily a question of maintaining contact with the retreating British forces, and foiling their evacuation plans. German infantry divisions were withdrawn from action due to a lack of mobility. The 2nd and 5th Panzerdivisions, the 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment and both mountain divisions launched a pursuit of the enemy forces.

To allow an evacuation of the main body of British forces, Wilson ordered the rear guard to make a last stand at the historic Thermopylae pass, the gateway to Athens. General Freyberg was given the task of defending the coastal pass, while Mackay was to hold the village of Brallos. After the battle Mackay was quoted as saying "I did not dream of evacuation; I thought that we'd hang on for about a fortnight and be beaten by weight of numbers." When the order to retreat was received on the morning of 23 April, it was decided that each of the two positions was to be held by one brigade each. These brigades, the Australian 19th and 6th New Zealand were to hold the passes as long as possible, allowing the other units to withdraw. The Germans attacked at 11:30 on 24 April, met fierce resistance, lost 15 tanks and sustained considerable casualties. The Allies held out the entire day; with the delaying action accomplished, they retreated in the direction of the evacuation beaches and set up another rearguard at Thebes. The Panzer units launching a pursuit along the road leading across the pass made slow progress because of the steep gradient and a large number of difficult hairpin bends.

, where they erected a last obstacle in front of Athens. The motorcycle battalion of the 2nd Panzerdivision, which had crossed to the island of Euboea

to seize the port of Chalcis

, and had subsequently returned to the mainland, was given the mission of outflanking the British rear guard. The motorcycle troops encountered only slight resistance, and on the morning of 27 April 1941, the first Germans entered Athens, followed by armoured cars, tank

s, and infantry

. They captured intact large quantities of POL (petroleum

, oil and lubricants) several thousand tons of ammunition, ten trucks loaded with sugar and ten truckloads of other rations in addition to various other equipment, weapons, and medical supplies. The people of Athens had been expecting the Germans to enter the city for several days and kept themselves confined to their homes with their windows shut. The previous night, Athens Radio had made the following announcement:

The Germans drove straight to the Acropolis

and raised the Nazi flag. According to the most popular account of the events, the Evzone

soldier on guard duty, Konstantinos Koukidis

, took down the Greek flag, refusing to hand it to the invaders wrapped himself in it, and jumped off the Acropolis. Whether the story was true or not, many Greeks believed it and viewed the soldier as a martyr

.

General Archibald Wavell

General Archibald Wavell

—the commander of British Army forces in the Middle East, when in Greece from 11-13 April—had warned Wilson that he must expect no reinforcements, and had authorised Major General Freddie de Guingand

to discuss evacuation plans with certain responsible officers. Nevertheless, the British could not at this stage adopt or even mention this course of action; the suggestion had to come from the Greek Government. The following day Papagos made the first move when he suggested to Wilson that W Force should be withdrawn. Wilson informed Middle East Headquarters, and on 17 April Rear admiral

H. T. Baillie-Grohman was sent to Greece to prepare for the evacuation. That day Wilson hastened to Athens where he attended a conference with the King, Papagos, d'Albiac and Rear admiral Turle. In the evening, Koryzis after telling the King that he felt he had failed him in the task entrusted to him, committed suicide. On 21 April, the final decision for the evacuation of the Commonwealth forces to Crete

and Egypt

was taken, and Wavell—in confirmation of verbal instructions—sent his written orders to Wilson.* Richter (1998), 566–567, 580–581

5,200 men, most of which belonged to the 5th New Zealand Brigade were evacuated on the night of 24 April from Porto Rafti

of East Attica

, while the 4th New Zealand Brigade remained to block the narrow road to Athens, which was dubbed the 24 Hour Pass by the New Zealanders. On 25 April (Anzac Day

), the few RAF squadrons left Greece (d'Albiac established his headquarters in Heraklion

, Crete

), and some 10,200 Australian troops were evacuated from Nauplion and Megara

.* Richter (1998), 584–585 2,000 more men had to wait until 27 April, because Ulster Prince ran aground in shallow waters close to Nauplion. Because of this event, the Germans realised that the evacuation was also taking place from the ports of East Peloponnese.

On 25 April, the Germans staged an airborne operation to seize the bridges over the Corinth canal

, with the double aim of both cutting off the British line of retreat and securing their own way across the isthmus

. The attack met with initial success, until a stray British shell destroyed the bridge. The 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment (LSSAH), assembled at Ioannina, thrust along the western foothills of the Pindus Mountains via Arta

to Missolonghi, and crossed over to the Peloponnese at Patras

in an effort to gain access to the isthmus from the west. Upon their arrival at 17:30 on 27 April, the SS forces learned that the paratroops had already been relieved by Army units advancing from Athens.

The erection of a temporary bridge across the Corinth canal permitted 5th Panzerdivision units to pursue the enemy forces across the Peloponnese. Driving via Argos

to Kalamata

, from where most Allied units had already begun to evacuate, they reached the south coast on 29 April, where they were joined by SS troops arriving from Pyrgos

. The fighting on the Peloponnese consisted merely of small-scale engagements with isolated groups of British troops who had been unable to make ship in time. The attack came a few days too late to cut off the bulk of the British troops in Central Greece, but did manage to isolate the Australian 16th

and 17th

Brigades. By 30 April, the evacuation of about 50,000 soldiers was completed, but was heavily contested by the German Luftwaffe, which sank at least 26 troop-laden ships. The Germans captured around 8,000 Commonwealth (including 2,000 Cypriots and Palestinians) and Yugoslav troops in Kalamata who had not been evacuated, while liberating many Italian prisoners from POW camps.*

* Richter (1998), 595

On 13 April 1941, Hitler issued his Directive No. 27, which illustrated his future occupying policy in Greece. He finalised jurisdiction in the Balkans with his Directive No. 31 issued on 9 June. Mainland Greece was divided between Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria. German forces occupied the strategically more important areas, namely Athens

On 13 April 1941, Hitler issued his Directive No. 27, which illustrated his future occupying policy in Greece. He finalised jurisdiction in the Balkans with his Directive No. 31 issued on 9 June. Mainland Greece was divided between Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria. German forces occupied the strategically more important areas, namely Athens

, Thessaloniki

with Central Macedonia

, and several Aegean islands, including most of Crete. They also occupied Florina, which was claimed by both Italy and Bulgaria. On the same day that Tsolakoglou offered his surrender, the Bulgarian Army invaded Thrace

. The goal was to gain an Aegean Sea outlet in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. The Bulgarians occupied territory between the Strimon river

and a line of demarcation running through Alexandroupoli

and Svilengrad

west of the Evros

river. The remainder of Greece was left to Italy. Italian troops started occupying the Ionian and Aegean islands on 28 April. On 2 June, they occupied the Peloponnese; on 8 June, Thessaly

; and on 12 June, most of Attica

.

The occupation of Greece—during which civilians suffered terrible hardships, many died from privation and hunger—proved to be a difficult and costly task. It led to the creation of several resistance group

s, which launched guerilla attacks against the occupying forces and set up espionage networks.

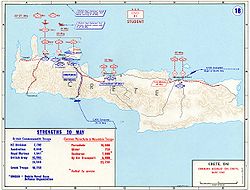

On 25 April 1941, King George II and his government left the Greek mainland for Crete, which was attacked by Nazi forces on 20 May 1941.* The Germans employed parachute forces in a massive airborne invasion, and launched their offensive against three main airfields of the island in Maleme

, Rethymno

, and Heraklion

. After seven days of fighting and tough resistance, Allied commanders decided that the cause was hopeless, and ordered a withdrawal from Sfakia

. By 1 June 1941, the evacuation of Crete by the Allies was complete and the island was under German occupation. In light of the heavy casualties suffered by the elite 7th Fliegerdivision, Hitler forbade further airborne operations. General Kurt Student would dub Crete "the graveyard of the German paratroopers" and a "disastrous victory." During the night of 24 May, George II and his government were evacuated from Crete to Egypt.

In enumerating the reasons for the complete German victory in Greece, the following factors seem to have been of the greatest significance:

After the Allies' defeat, the decision to send British forces into Greece was met with fierce criticism in Britain. Field Marshal Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff during World War II, considered intervention in Greece to be "a definite strategic blunder", as it denied Wavell the necessary reserves to complete the conquest of Italian-held Libya

, or to successfully withstand Erwin Rommel

's Afrika Korps

March offensive. It thus prolonged the North African Campaign

, which otherwise might have been successfully concluded within 1941.

In 1947 de Guingand

asked the British government to recognise the mistakes it had made when it laid out its strategy in Greece. Buckley—on the other hand—argued that if Britain had not honored its commitment of 1939 to defend Greece's independence, it would have severely damaged the ethical rationalisations of its struggle against Nazi Germany. According to Professor of History, Heinz Richter, Churchill tried through the campaign in Greece to influence the political atmosphere in the United States, and he insisted on this strategy even after the defeat. According to John Keegan

, "the Greek campaign had been an old-fashioned gentlemen's war, with honor given and accepted by brave adversaries on each side", and the Greek and Allied forces, being vastly outnumbered, "had, rightly, the sensation of having fought the good fight."

Freyberg and Blamey also had serious doubts about the feasibility of the operation, but failed to advise their governments of their reservations and apprehensions. The campaign caused a furore in Australia, when it became known that when he received his first warning of the move to Greece on 18 February 1941, General Blamey was worried but had not informed the Australian Government. He had been told by General Wavell that Prime Minister

Menzies

had already given his approval of the plan. Indeed, the proposal had been accepted by a meeting of the War Cabinet in London at which Mr Menzies was present, but the Australian Prime Minister had been told by Churchill that both Freyberg and Blamey approved of the expedition. On 5 March, in a letter to Menzies, Blamey said that "the plan is, of course, what I feared: piecemeal dispatch to Europe", and the next day, he called the operation "most hazardous". However, thinking that he was agreeable, the Australian Government had already committed the Australian Imperial Force to the Greek Campaign.

In 1942, members of the British Parliament characterised the campaign in Greece as a "political and sentimental decision". Eden rejected the criticism and argued that the UK's decision was unanimous, and asserted that the Battle of Greece delayed the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union. This is an argument that some historians such as Keegan have also used in order to prove that Greek resistance may have been a turning point in World War II.* Keegan (2005), 144 According to the film-maker and friend of Adolf Hitler Leni Riefenstahl

, Hitler said that "if the Italians hadn't attacked Greece and needed our help, the war would have taken a different course. We could have anticipated the Russian cold by weeks and conquered Leningrad and Moscow. There would have been no Stalingrad

". Despite his reservations, Brooke seems also to have conceded that the start of the offensive against the Soviet Union was in fact delayed because of the Balkan Campaign. John N. Bradley and Thomas B. Buell conclude that "although no single segment of the Balkan campaign forced the Germans to delay Barbarossa, obviously the entire campaign did prompt them to wait." On the other hand, Richter calls Eden's arguments a "falsification of history". Basil Liddell Hart

and de Guingand asserted that, even if Operation Marita delayed the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, this was not enough to vindicate the decision of the British government, because this was not its initial strategic goal. In 1952, the Historical Branch of the UK Cabinet Office concluded that the Balkan Campaign had no influence on the launching of Operation Barbarossa. According to Robert Kirchubel, "the main causes for deferring Barbarossa's start from 15 May 15-22 June were incomplete logistical arrangements, and an unusually wet winter that kept rivers at full flood until late spring."

, the Führer "wanted to give the Greeks an honorable settlement in recognition of their brave struggle, and of their blamelessness for this war: after all the Italians had started it." Inspired by the Greek resistance during the Italian and German invasions, Churchill said, "Hence we will not say that Greeks fight like heroes, but that heroes fight like Greeks". In response to a letter from George VI dated 3 December 1940, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt

stated that "all free peoples are deeply impressed by the courage and steadfastness of the Greek nation", and in a letter to the Greek ambassador dated 29 October 1942, he wrote that "Greece has set the example which every one of us must follow until the despoilers of freedom everywhere have been brought to their just doom."

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

forces, while the Germans' Axis

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

allies Italy and Bulgaria

Kingdom of Bulgaria

The Kingdom of Bulgaria was established as an independent state when the Principality of Bulgaria, an Ottoman vassal, officially proclaimed itself independent on October 5, 1908 . This move also formalised the annexation of the Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia, which had been under the control...

played secondary roles. The Battle of Greece is usually distinguished from the Greco-Italian War

Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War was a conflict between Italy and Greece which lasted from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. It marked the beginning of the Balkans Campaign of World War II...

fought in northwestern Greece and southern Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

from October 1940, as well as from the Battle of Crete

Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete was a battle during World War II on the Greek island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May 1941, when Nazi Germany launched an airborne invasion of Crete under the code-name Unternehmen Merkur...

fought in late May. These operations, along with the Invasion of Yugoslavia

Invasion of Yugoslavia

The Invasion of Yugoslavia , also known as the April War , was the Axis Powers' attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II...

, comprise the Balkans Campaign of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

The Balkans Campaign began with the Italian invasion of Greece on 28 October 1940. Within weeks, the Italians were driven out of Greece and Greek forces pushed on to occupy much of southern Albania. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack failed, and Germany was forced to come to the aid of its ally. Operation Marita began on 6 April 1941, with German troops invading Greece through Bulgaria in an effort to secure its southern flank. The combined Greek and British Commonwealth forces fought back with great tenacity, but were vastly outnumbered and out-gunned, and finally collapsed. Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

fell on 27 April, however the British managed to evacuate about 50,000 troops. The Greek campaign ended in a quick and complete German victory with the fall of Kalamata

Kalamata

Kalamata is the second-largest city of the Peloponnese in southern Greece. The capital and chief port of the Messenia prefecture, it lies along the Nedon River at the head of the Messenian Gulf...

in the Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

; it was over within 24 days. The conquest of Greece was completed through the capture of Crete a month later. Greece remained under occupation by the Axis powers until October 1944.

Some historians regard the German campaign in Greece as decisive in determining the course of World War II, maintaining that it fatally delayed the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

. Others hold that the campaign had no influence on the launching of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

as monsoon conditions in the Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

would have postponed Axis operations regardless. Others believed British intervention in Greece as a hopeless undertaking, a "political and sentimental decision" or even a "definite strategic blunder." It has also been suggested the British strategy was to create a barrier in Greece, to protect Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, the only (neutral) country standing between an Axis block in the Balkans and the oil-rich Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

.

Greco-Italian War

At the outbreak of World War II, Ioannis MetaxasIoannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas was a Greek general, politician, and dictator, serving as Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941...

—the Prime Minister of Greece

Prime Minister of Greece

The Prime Minister of Greece , officially the Prime Minister of the Hellenic Republic , is the head of government of the Hellenic Republic and the leader of the Greek cabinet. The current interim Prime Minister is Lucas Papademos, a former Vice President of the European Central Bank, following...

—sought to maintain a position of neutrality

Neutral country

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

. However, Greece was increasingly subject to pressure from Italy, which culminated in the Italian submarine Delfinos torpedoing of the Greek cruiser on 15 August 1940. Italian leader Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

was irritated that Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

had not consulted him on his war policy, and wished to establish his independence. He hoped to match the military success of the Germans through a victorious attack on Greece, a country he regarded as an easy opponent.* Goldstein (1992), 53 On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision to invade Greece. In the early hours of 28 October, Italian Ambassador Emmanuel Grazzi presented Metaxas with a three-hour ultimatum, in which he demanded free passage for troops to occupy unspecified "strategic sites" within Greek territory. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum (the refusal is commemorated as Ohi Day, a national holiday in Greece), but even before its expiration, Italian troops had invaded Greece through Albania. The principal Italian thrust was directed towards Epirus, but made little progress. During the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas the Italians fought their way across the Thyamis (Kalamas) river, but were then forced to a halt. Within three weeks, a successful Greek counterattack was underway. A number of towns in southern Albania fell to Greek forces, and neither a change in Italian commanders, nor the arrival of a substantial number of reinforcements had much effect.

After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched a large-scale counterattack across the centre of the front on 9 March 1941, which, despite the superiority of the Italian armed forces, failed. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the counterattack, and then left Albania 12 days later.* More U-boat Aces Hunted down, OnWar.Com Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated meagre military resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather and launched an attack without the advantage of surprise and without the support of the Bulgarians.* Rodogno (2006), 29–30 Even elementary precautions, such as the issue of winter clothing had not been taken. Nor had Mussolini taken into consideration the recommendations of the Italian Commission of War Production, which had warned that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of continuous warfare until 1949.

During the six month fight against Italy, the Greek army made local gains by eliminating enemy salient

Salients, re-entrants and pockets

A salient is a battlefield feature that projects into enemy territory. The salient is surrounded by the enemy on three sides, making the troops occupying the salient vulnerable. The enemy's line facing a salient is referred to as a re-entrant...

s. Nevertheless, Greece did not have a substantial armaments industry, and both its equipment and ammunition supplies increasingly relied on stocks captured by British forces from defeated Italian armies in North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

. In order to man the battlefront in Albania, the Greek command was forced to make withdrawals from Eastern Macedonia

Macedonia (Greece)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of Greece in Southern Europe. Macedonia is the largest and second most populous Greek region...

and Western Thrace

Western Thrace

Western Thrace or simply Thrace is a geographic and historical region of Greece, located between the Nestos and Evros rivers in the northeast of the country. Together with the regions of Macedonia and Epirus, it is often referred to informally as northern Greece...

. Anticipation of a German attack expedited the need to reverse the position; the available forces were proving unable to sustain resistance on both fronts. The Greek command decided to support its success in Albania, regardless of how the situation might develop under the impact of a German attack from the Bulgarian border.

|

|

|

| First Italian offensive October 28 – November 13, 1940. |

Greek counter-offensive November 14, 1940 – March, 1941. |

Second Italian offensive March 9 – April 23, 1941. |

Hitler's decision to attack and British aid to Greece

Hitler intervened on 4 November 1940, four days after the British took both CreteCrete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

and Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

. The Führer

Führer

Führer , alternatively spelled Fuehrer in both English and German when the umlaut is not available, is a German title meaning leader or guide now most associated with Adolf Hitler, who modelled it on Benito Mussolini's title il Duce, as well as with Georg von Schönerer, whose followers also...

ordered his Army General Staff to prepare for an invasion of Northern Greece via Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

and Bulgaria. His plans for this campaign were incorporated into a master plan aimed at depriving the British of their Mediterranean bases.* On 12 November, the German Armed Forces High Command

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht was part of the command structure of the armed forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.- Genesis :...

issued Directive No. 18, in which they scheduled simultaneous operations against Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

and Greece for the following January. However, in December 1940, German ambition in the Mediterranean underwent considerable revision when Spain's General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

rejected plans for an attack on Gibraltar. Consequently, Germany's offensive in Southern Europe

Southern Europe

The term Southern Europe, at its most general definition, is used to mean "all countries in the south of Europe". However, the concept, at different times, has had different meanings, providing additional political, linguistic and cultural context to the definition in addition to the typical...

was restricted to the campaign against Greece. The Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940. The document outlined the Greek campaign under the code designation "Operation Marita", and planned for German occupation of the northern coast of the Aegean Sea

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

by March 1941. It also planned for the seizure of the entire Greek mainland, if that became necessary.*

* Svolopoulos (1997), 288 During a hastily called meeting of Hitler's staff after the unexpected 27 March coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

against the Yugoslav government, orders for the future campaign in Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

were drafted, as well as changes to the plan for the attack on Greece. On 6 April, both Greece and Yugoslavia were to be attacked.* McClymont, 158–159

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

was obliged to assist Greece by the declaration of 1939, which stated that in the event of a threat to Greek or Romanian independence, "His Majesty's Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Greek or Romanian Government [...] all the support in their power." The first British effort was the deployment of Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

squadrons commanded by Air Commodore

Air Commodore

Air commodore is an air-officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force...

John d'Albiac

John D'Albiac

Air Marshal Sir John Henry D'Albiac KCVO, KBE, CB, DSO was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force during World War II.-Biography:...

, which were sent in November 1940. With the consent of the Greek government, British forces were dispatched to Crete on 31 October to guard Suda Bay, enabling the Greek government to redeploy the 5th Cretan Division

5th Cretan Division

The 5th Cretan Division , formerly the 5th Infantry Division and commonly referred to simply as the Cretan Division , is a formation of the Hellenic Army...

to the mainland.

On 17 November 1940, Metaxas proposed to the British government the undertaking of a joint offensive in the Balkans with the Greek strongholds in southern Albania as the base of the operations. The British were reluctant to discuss Metaxas' proposal, because the deployment of troops necessary for implementing the Greek plan would seriously endanger the Commonwealth military operations in North Africa. During a meeting of British and Greek military and political leaders in Athens on 13 January 1941, General

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

Alexandros Papagos—Commander-in-Chief

Commander-in-Chief

A commander-in-chief is the commander of a nation's military forces or significant element of those forces. In the latter case, the force element may be defined as those forces within a particular region or those forces which are associated by function. As a practical term it refers to the military...

of the Hellenic Army

Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army , formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece.The motto of the Hellenic Army is , "Freedom Stems from Valor", from Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War...

—asked Britain for nine fully equipped divisions and corresponding air support. The British responded that, because of their commitment to the fight in North Africa, all they could offer was the immediate dispatch of a small token force of less than divisional strength. This offer was rejected by the Greeks who feared that the arrival of such a contingent would precipitate a German attack without giving them any sizable assistance. British help would be requested if and when German troops crossed the Danube from Romania into Bulgaria.* Blau (1953), 71–72

British expeditionary force

Churchill held to his ambition to recreate a Balkan Front comprising Yugoslavia, Greece and TurkeyTurkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, and instructed Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957...

and Sir John Dill

John Dill

Field Marshal Sir John Greer Dill, GCB, CMG, DSO was a British commander in World War I and World War II. From May 1940 to December 1941 he was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, the professional head of the British Army, and subsequently in Washington, as Chief of the British Joint Staff...

to resume negotiations with the Greek government. A meeting attended by Eden and the Greek leadership, including King George II

George II of Greece

George II reigned as King of Greece from 1922 to 1924 and from 1935 to 1947.-Early life, first period of kingship and exile:George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near Athens, the eldest son of King Constantine I of Greece and his wife, Princess Sophia of Prussia...

, Prime Minister Alexandros Koryzis—the successor of Metaxas, who had died on 29 January 1941—and Papagos took place in Athens on 22 February. There the decision to send a British Commonwealth expeditionary force was made. German troops had been massing in Romania and on 1 March 1941, Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

forces began to move into Bulgaria. At the same time, the Bulgarian Army mobilised and took up positions along the Greek frontier.

On 2 March, Operation Lustre

Operation Lustre

Operation Lustre was an action during World War II, involving the dispatch of British, Australian, New Zealand and Polish troops from Egypt to Greece in March and April 1941, in response to the failed Italian invasion and the looming threat of German intervention, revealed through Ultra.It was seen...

—the transportation of troops and equipment to Greece—began and 26 troopship

Troopship

A troopship is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime...

s arrived at the port of Piraeus

Piraeus

Piraeus is a city in the region of Attica, Greece. Piraeus is located within the Athens Urban Area, 12 km southwest from its city center , and lies along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf....

. On 3 April, during a meeting of British, Yugoslav, and Greek military representatives, the Yugoslavs promised to block the Strymon valley

Struma River

The Struma or Strymónas is a river in Bulgaria and Greece. Its ancient name was Strymōn . Its catchment area is 10,800 km²...

in case of a German attack across their territory. During this meeting, Papagos laid stress on the importance of a joint Greco-Yugoslavian offensive against the Italians, as soon as the Germans launched their offensive against the two countries. Until 24 April, more than 62,000 Commonwealth troops (British, Australians, New Zealanders, Palestinians and Cypriots

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

), were sent to Greece, comprising the 6th Australian Division, the New Zealand 2nd Division

New Zealand 2nd Division

The 2nd New Zealand Division was a formation of the New Zealand Military Forces during World War II. It was commanded for most of its existence by Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg, and fought in Greece, Crete, the Western Desert and Italy...

, and the British 1st Armoured Brigade

British 1st Armoured Brigade

The 1st Armoured Brigade was a regular British Army unit formed from the redesignation of the 1st Light Armoured Brigade on 3 September 1939.-Second World War History:...

. The three formations later became known as 'W' Force, after their commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. Air Commodore Sir John D'Albiac commanded the British air forces in Greece.

Topography

To enter Northern Greece, the German army was compelled to cross the Rhodope mountainsRhodope Mountains

The Rhodopes are a mountain range in Southeastern Europe, with over 83% of its area in southern Bulgaria and the remainder in Greece. Its highest peak, Golyam Perelik , is the seventh highest Bulgarian mountain...

, which possessed few river valleys or passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion courses were located west of Kyustendil

Kyustendil

Kyustendil is a town in the far west of Bulgaria, the capital of Kyustendil Province, with a population of 44 416 . Kyustendil is situated in the southern part of the Kyustendil Valley, 90 km southwest of Sofia...

; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Strimon valley to the south. Greek border fortifications had been adapted for the terrain, and a formidable defence system covered the few available roads. The Strimon and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier, and both of their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line

Metaxas Line

The Metaxas Line was a chain of fortifications constructed along the line of the Greco-Bulgarian border, designed to protect Greece in case of a Bulgarian invasion after the rearmament of Bulgaria. It was named after Ioannis Metaxas, the then Prime Minister of Greece, and chiefly consists of...

. This system of concrete pillboxes and field fortifications was constructed along the Bulgarian border in the late 1930s, and was based on principles similar to those applied to the Maginot Line

Maginot Line

The Maginot Line , named after the French Minister of War André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, tank obstacles, artillery casemates, machine gun posts, and other defences, which France constructed along its borders with Germany and Italy, in light of its experience in World War I,...

. Its strength resided mainly in the inaccessibility of the intermediate terrain leading up to the defence positions.* Blau (1953), 75

Strategic factors

Rhodope Mountains

The Rhodopes are a mountain range in Southeastern Europe, with over 83% of its area in southern Bulgaria and the remainder in Greece. Its highest peak, Golyam Perelik , is the seventh highest Bulgarian mountain...

, Epirus

Epirus (region)

Epirus is a geographical and historical region in southeastern Europe, shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay of Vlorë in the north to the Ambracian Gulf in the south...

, Pindus

Pindus

The Pindus mountain range is located in northern Greece and southern Albania. It is roughly 160 km long, with a maximum elevation of 2637 m . Because it runs along the border of Thessaly and Epirus, the Pindus range is often called the "spine of Greece"...

, and Olympus

Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus is the highest mountain in Greece, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia, about 100 kilometres away from Thessaloniki, Greece's second largest city. Mount Olympus has 52 peaks. The highest peak Mytikas, meaning "nose", rises to 2,917 metres...

mountains offered many opportunities to stop an invader. However, adequate air power was required to prevent defending ground forces from becoming trapped in the many defile

Defile (geography)

Defile is a geographic term for a narrow pass or gorge between mountains or hills. It has its origins as a military description of a pass through which troops can march only in a narrow column or with a narrow front...

s. Although an invading force from Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

could be stopped by a relatively small number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, the northeastern part of the country was difficult to defend against an attack from the north.

Following a conference in Athens that March, the British command believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon

Haliacmon

The Haliacmon is the longest river in Greece, with a total length of . Haliacmon is the traditional English name for the river, but many sources cite the formerly official Katharevousa version of the name, Aliákmon...

Line—a short front facing northeastward along the Vermion Mountains

Vermion Mountains

The Vermio Mountains is a mountain range between Imathia and Kozani Prefecture in west-central Macedonia. The range is west of the plain of Kambania. The town of Veria, which is the capital of Imathia prefecture, is built οn the foot of these mountains...

, and the lower Haliacmon

Haliacmon