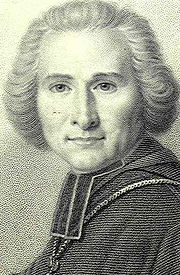

Henri Grégoire

Encyclopedia

- For the 20th-century Belgian Byzantinologist, see Henri Grégoire (historian)Henri Grégoire (historian)Henri Grégoire was an eminent scholar of the Byzantine Empire, virtually the founder of Byzantine studies in Belgium.Grégoire spent most of his teaching career at the Université libre de Bruxelles...

Henri Grégoire (ɑ̃ʁi ɡʁeɡwaʁ; 4 December 1750 – 20 May 1831), often referred to as Abbé Grégoire, was a French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

Roman Catholic priest, constitutional bishop

Constitutional bishop

During the French Revolution, a constitutional bishop was a Roman Catholic bishop elected from among the clergy who had sworn to uphold the Civil Constitution of the Clergy between 1791 and 1801. Constitutional bishops were often priests with less or more moderate Gallican and partisan ideas, of a...

of Blois

Blois

Blois is the capital of Loir-et-Cher department in central France, situated on the banks of the lower river Loire between Orléans and Tours.-History:...

and a revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

ary leader. He was an ardent abolitionist and supporter of universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, and was a founding member of the Bureau des longitudes

Bureau des Longitudes

The Bureau des Longitudes is a French scientific institution, founded by decree of 25 June 1795 and charged with the improvement of nautical navigation, standardisation of time-keeping, geodesy and astronomical observation. During the 19th century, it was responsible for synchronizing clocks...

, the Institut de France

Institut de France

The Institut de France is a French learned society, grouping five académies, the most famous of which is the Académie française.The institute, located in Paris, manages approximately 1,000 foundations, as well as museums and chateaux open for visit. It also awards prizes and subsidies, which...

, and the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers

Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers

The Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers , or National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, is a doctoral degree-granting higher education establishment operated by the French government, dedicated to providing education and conducting research for the promotion of science and industry...

.

Early life

He was born at VéhoVého

Vého is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in north-eastern France.-See also:*Communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department...

near Lunéville

Lunéville

Lunéville is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in France.It is a sub-prefecture of the department and lies on the Meurthe River.-History:...

, the son of a tailor. Educated at the Jesuit college at Nancy, he became curé (priest) of Emberménil

Emberménil

Emberménil is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in north-eastern France.-See also:*Communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department...

in 1782. In 1783 he was crowned by the Academy of Nancy for his Eloge de la poésie, and in 1788 by that of Metz

Metz

Metz is a city in the northeast of France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers.Metz is the capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. Located near the tripoint along the junction of France, Germany, and Luxembourg, Metz forms a central place...

for an Essai sur la régénération physique et morale des Juifs.

He was elected in 1789 by the clergy of the bailliage of Nancy to the Estates-General

Estates-General of 1789

The Estates-General of 1789 was the first meeting since 1614 of the French Estates-General, a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the nobility, the Church, and the common people...

, where he soon made his name as one of the group of clerical and lay deputies of Jansenist

Jansenism

Jansenism was a Christian theological movement, primarily in France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. The movement originated from the posthumously published work of the Dutch theologian Cornelius Otto Jansen, who died in 1638...

or Gallican

Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarchs' authority or the State's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope's...

sympathies who supported the Revolution. He was one of the first of the clergy to join the third estate, and contributed notably to the union of the three orders

French States-General

In France under the Old Regime, the States-General or Estates-General , was a legislative assembly of the different classes of French subjects. It had a separate assembly for each of the three estates, which were called and dismissed by the king...

; he presided at the session which lasted sixty-two hours while the Bastille was being attacked

Storming of the Bastille

The storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris on the morning of 14 July 1789. The medieval fortress and prison in Paris known as the Bastille represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. While the prison only contained seven inmates at the time of its storming, its fall was the flashpoint...

by the people, and spoke vehemently against the enemies of the nation. He later took a leading role in the abolition of the privileges of the nobles and the Church.

Constitutional bishop

Under the new Civil Constitution of the ClergyCivil Constitution of the Clergy

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was a law passed on 12 July 1790 during the French Revolution, that subordinated the Roman Catholic Church in France to the French government....

, to which he was the first priest to take the oath (27 December 1790), he was elected bishop by two départements. He selected that of Loir-et-Cher

Loir-et-Cher

Loir-et-Cher is a département in north-central France named after the rivers Loir and Cher.-History:Loir-et-Cher is one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution on 4 March 1790. It was created from parts of the former provinces of Orléanais and...

, taking the old title of bishop of Blois, and for ten years (1791–1801) ruled his diocese with exemplary zeal. An ardent republican, it was he who in the first session of the National Convention

National Convention

During the French Revolution, the National Convention or Convention, in France, comprised the constitutional and legislative assembly which sat from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795 . It held executive power in France during the first years of the French First Republic...

(21 September 1792) proposed the motion for the abolition of the monarchy

Proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy

During the French Revolution, the proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy was a proclamation by the National Convention of France announcing that it had abolished the French monarchy on 21 September 1792.-Prelude:...

, in a speech in which occurred the memorable phrase that "Kings are in morality what monsters are in the world of nature.".

On 15 November he delivered a speech in which he demanded that king Louis XVI

Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre until 1791, and then as King of the French from 1791 to 1792, before being executed in 1793....

should be brought to trial, and immediately afterwards was elected president of the Convention, over which he presided in his episcopal dress. During the trial, being absent with other three colleagues on a mission for the union of Savoy

Savoy

Savoy is a region of France. It comprises roughly the territory of the Western Alps situated between Lake Geneva in the north and Monaco and the Mediterranean coast in the south....

to France, he along with them wrote a letter urging the condemnation of the king, but attempted to save the life of the monarch by proposing that the death penalty should be suspended.

When, on 7 November 1793, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gobel

Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gobel

Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gobel was a French Roman Catholic cleric and politician of the Revolution.-Clerical career:...

, bishop of Paris, was intimidated into resigning his episcopal office at the bar of the Convention, Grégoire, who was temporarily absent, hearing what had happened, faced the indignation of many deputies, refusing to give up either his religion or his office. This display of courage ultimately saved him from the guillotine

Guillotine

The guillotine is a device used for carrying out :executions by decapitation. It consists of a tall upright frame from which an angled blade is suspended. This blade is raised with a rope and then allowed to drop, severing the head from the body...

.

Throughout the Reign of Terror

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror , also known simply as The Terror , was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of...

, in spite of attacks in the Convention, in the press, and on placards posted at the street corners, he appeared in the streets in his episcopal dress and daily said Mass

Mass (liturgy)

"Mass" is one of the names by which the sacrament of the Eucharist is called in the Roman Catholic Church: others are "Eucharist", the "Lord's Supper", the "Breaking of Bread", the "Eucharistic assembly ", the "memorial of the Lord's Passion and Resurrection", the "Holy Sacrifice", the "Holy and...

in his house. After Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre is one of the best-known and most influential figures of the French Revolution. He largely dominated the Committee of Public Safety and was instrumental in the period of the Revolution commonly known as the Reign of Terror, which ended with his...

's fall (the Thermidor

Thermidor

Thermidor was the eleventh month in the French Republican Calendar. The month was named after the French word thermal which comes from the Greek word "thermos" which means heat....

), he was the first to advocate the reopening of the churches (speech of 21 December 1794).

He also tried to get measures put in place for restraining the vandalism

Vandalism

Vandalism is the behaviour attributed originally to the Vandals, by the Romans, in respect of culture: ruthless destruction or spoiling of anything beautiful or venerable...

, extended his protection to several artists and writers, and devoted attention to the reorganization of the public libraries

Public library

A public library is a library that is accessible by the public and is generally funded from public sources and operated by civil servants. There are five fundamental characteristics shared by public libraries...

, the establishment of botanical garden

Botanical garden

A botanical garden The terms botanic and botanical, and garden or gardens are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word botanic is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens. is a well-tended area displaying a wide range of plants labelled with their botanical names...

s, and the improvement of technical education. In fact, he coined the term, vandalism, in a series of three monumental reports in 1794, i.e., Report on the Destruction Brought About by Vandalism,... He is credited by scholars (e.g. Joseph Sax) with the idea of preservation of cultural objects

Art conservation and restoration

Conservation-restoration, also referred to as conservation, is a profession devoted to the preservation of cultural heritage for the future. Conservation activities include examination, documentation, treatment, and preventive care...

.

Advocate of racial equality

In October 1789, Grégoire took a great interest in abolitionismAbolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

, after meeting Julien Raimond

Julien Raimond

Julien Raimond was an indigo planter in the French colony of Saint-Domingue .-Early activism:He was born a free man of color, the son of a French colonist and the mulatto daughter of a planter, in the isolated South province of the colony. Raimond owned over 100 slaves by the 1780s, and was one of...

, a free colored

Gens de couleur

Gens de couleur is a French term meaning "people of color." The term was commonly used in France's West Indian colonies prior to the abolition of slavery, where it was a short form of gens de couleur libres ....

planter from Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue

The labour for these plantations was provided by an estimated 790,000 African slaves . Between 1764 and 1771, the average annual importation of slaves varied between 10,000-15,000; by 1786 it was about 28,000, and from 1787 onward, the colony received more than 40,000 slaves a year...

who was trying to win admission to the Constituent Assembly

National Constituent Assembly

The National Constituent Assembly was formed from the National Assembly on 9 July 1789, during the first stages of the French Revolution. It dissolved on 30 September 1791 and was succeeded by the Legislative Assembly.-Background:...

as a representative of his group. He published numerous pamphlets and later, books, on the subject of racial equality, and became an influential member of the Society of the Friends of the Blacks

Society of the Friends of the Blacks

The Society of the Friends of the Blacks was a group of French men and women, mostly white, who were abolitionists . The Society was created in Paris in 1788, and remained in existence until 1793...

. It was on Grégoire's motion in May 1791 that the Constituent Assembly passed its first law admitting some wealthy free men of colour in the French colonies to the same rights as whites. In addition, Gregoire was considered a friend of the Jews. He argued that in his anti-Semitic society the supposed degeneracy of Jews was not inherent, but rather a result of their circumstances. He blamed the way the Jews had been treated, persecution by Christians, and the "ridiculous" teachings of their rabbis, for their condition, and believed they could be brought into mainstream society and made citizens.

Annihilating the dialects of France

Abbé Grégoire is also notorious for writing his Rapport sur la Nécessité et les Moyens d'anéantir les Patois et d'universaliser l'Usage de la Langue française (Report on the necessity and means to annihilate the patois and to universalise the use of the French language), which he presented on 4 June 1794 to the National ConventionNational Convention

During the French Revolution, the National Convention or Convention, in France, comprised the constitutional and legislative assembly which sat from 20 September 1792 to 26 October 1795 . It held executive power in France during the first years of the French First Republic...

. According to his own findings, a vast majority of people in France spoke one of 33 dialects or patois

Patois

Patois is any language that is considered nonstandard, although the term is not formally defined in linguistics. It can refer to pidgins, creoles, dialects, and other forms of native or local speech, but not commonly to jargon or slang, which are vocabulary-based forms of cant...

and he argued that French had to be imposed on the population and all other dialects eradicated. In his hardly reliable classification, notable mistakes and prejudices included Corsican

Corsican language

Corsican is a Italo-Dalmatian Romance language spoken and written on the islands of Corsica and northern Sardinia . Corsican is the traditional native language of the Corsican people, and was long the vernacular language alongside the Italian, official language in Corsica until 1859, which was...

and Alsatian

Alsatian language

Alsatian is a Low Alemannic German dialect spoken in most of Alsace, a region in eastern France which has passed between French and German control many times.-Language family:...

being described as "highly degenerate" (très-dégénérés) forms of Italian and German while Occitan was decomposed into a variety of syntactically loose local remnants of the language of troubadour

Troubadour

A troubadour was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages . Since the word "troubadour" is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a trobairitz....

s with no intelligibility among them, and had to be abandoned in favour of the language of the capital. This, coupled with Jules Ferry

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.- Early life :Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to...

's policy less than a century later, led to the weakening of most unofficial languages in France, all of them being subsequently banned from public documents, administration and school. One effect of this policy is Vergonha

Vergonha

La vergonha is what Occitans call the effects of various policies of the government of France on its citizens whose mother tongue was a so-called patois, specifically langue d'oc...

.

Political career after 1795

After the establishment of the DirectoryFrench Constitution of 1795

The Constitution of 22 August 1795 was a national constitution of France ratified by the National Convention on 22 August 1795 during the French Revolution...

in 1795, Grégoire was elected to the Council of Five Hundred

Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred , or simply the Five Hundred was the lower house of the legislature of France during the period commonly known as the Directory , from 22 August 1795 until 9 November 1799, roughly the second half of the period generally referred to as the...

. After Napoleon Bonaparte took power in 1799

18 Brumaire

The coup of 18 Brumaire was the coup d'état by which General Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the French Directory, replacing it with the French Consulate...

he became a member of the Corps Législatif

Corps législatif

The Corps législatif was a part of the French legislature during the French Revolution and beyond. It is also the generic French term used to refer to any legislative body.-History:The Constitution of the Year I foresaw the need for a corps législatif...

, then of the Senate

French Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Parliament of France, presided over by a president.The Senate enjoys less prominence than the lower house, the directly elected National Assembly; debates in the Senate tend to be less tense and generally enjoy less media coverage.-History:France's first...

(1801). He took the lead in the national church councils of 1797 and 1801; but he was strenuously opposed to Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

's policy of reconciliation with the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

, and after the signature of the concordat he resigned his bishopric on 8 October 1801.

He was one of the minority of five in the Senate who voted against the proclamation of the French Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

, and he opposed the creation of a new French nobility

French nobility

The French nobility was the privileged order of France in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern periods.In the political system of the Estates General, the nobility made up the Second Estate...

and Napoleon's divorce from Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine de Beauharnais was the first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais had been guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she had been imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre's...

. Notwithstanding this, he was created a Count

Count

A count or countess is an aristocratic nobleman in European countries. The word count came into English from the French comte, itself from Latin comes—in its accusative comitem—meaning "companion", and later "companion of the emperor, delegate of the emperor". The adjective form of the word is...

and officer of the Légion d'honneur

Légion d'honneur

The Legion of Honour, or in full the National Order of the Legion of Honour is a French order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Consulat which succeeded to the First Republic, on 19 May 1802...

. During the later years of Napoleon's reign he travelled to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, but in 1814 he returned to France. He opposed Napoleon during the Hundred Days

Hundred Days

The Hundred Days, sometimes known as the Hundred Days of Napoleon or Napoleon's Hundred Days for specificity, marked the period between Emperor Napoleon I of France's return from exile on Elba to Paris on 20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII on 8 July 1815...

.

After the Restoration

After the restoration of the Bourbons, Grégoire remained influential, though as a revolutionary and a schismSchism (religion)

A schism , from Greek σχίσμα, skhísma , is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within...

atic bishop he was also the object of hatred by royalists. He was expelled from the Institut de France

Institut de France

The Institut de France is a French learned society, grouping five académies, the most famous of which is the Académie française.The institute, located in Paris, manages approximately 1,000 foundations, as well as museums and chateaux open for visit. It also awards prizes and subsidies, which...

, and forced into retirement.

In 1814 he published, De la constitution française de l'an 1814, in which be commented on the Charter

Charter of 1814

The French Charter of 1814 was a constitution granted by King Louis XVIII of France shortly after his restoration. The Congress of Vienna demanded that Louis bring in a constitution of some form before he was restored. It guaranteed many of the rights that most other countries in western Europe had...

from a Liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

point of view, and this reached its fourth edition in 1819, in which year he was elected to the Lower Chamber by the département of Isère

Isère

Isère is a department in the Rhône-Alpes region in the east of France named after the river Isère.- History :Isère is one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution on March 4, 1790. It was created from part of the former province of Dauphiné...

. This was considered a potentially harmful episode by the powers of the Quintuple Alliance

Quintuple Alliance

The Quintuple Alliance came into being at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, when France joined the Quadruple Alliance created by Russia, Austria, Prussia and the United Kingdom...

, and the question was raised of a fresh armed intervention in France under the terms of the secret Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818)

The Congress or Conference of Aix-la-Chapelle , held in the autumn of 1818, was primarily a meeting of the four allied powers Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia to decide the question of the withdrawal of the army of occupation from France and the nature of the modifications to be introduced in...

. To prevent this, Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII of France

Louis XVIII , known as "the Unavoidable", was King of France and of Navarre from 1814 to 1824, omitting the Hundred Days in 1815...

decided on a modification of the franchise; the Marquis Dessolles ministry resigned; and the first act of Count Decazes, the new premier, was to annul the election of Grégoire.

From this time onward the former bishop lived in retirement, occupying himself in literary pursuits and in correspondence with other intellectual figures of Europe. He was compelled to sell his library to obtain means of support.

Death and funeral

Despite his revolutionary, GallicanGallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarchs' authority or the State's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope's...

and liberal views, Grégoire considered himself a devout Catholic. During his last illness, he confessed to his parish curé, a priest of Jansenist sympathies, expressing his desire for the last sacraments of the Church. These Hyacinthe-Louis De Quelen

Hyacinthe-Louis De Quelen

Hyacinthe-Louis De Quelen was Archbishop of Paris.-Biography:Born in Paris, he was educated at the College of Navarre. Ordained in 1807, he served a year as Vicar-General of Saint-Brieuc and then became secretary to Cardinal Fesch. When the latter was sent back to his diocese, de Quelen exercised...

, the Archbishop of Paris

Archbishop of Paris

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Paris is one of twenty-three archdioceses of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The original diocese is traditionally thought to have been created in the 3rd century by St. Denis and corresponded with the Civitas Parisiorum; it was elevated to an archdiocese on...

, would only concede on condition that he retract his oath to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which he refused to do.

In defiance of the archbishop, the Abbé Baradère gave him the viaticum

Viaticum

Viaticum is a term used especially in the Roman Catholic Church for the Eucharist administered, with or without anointing of the sick, to a person who is dying, and is thus a part of the last rites...

, while the rite of extreme unction

Anointing of the Sick

Anointing of the Sick, known also by other names, is distinguished from other forms of religious anointing or "unction" in that it is intended, as its name indicates, for the benefit of a sick person...

was administered by the Abbé Guillon

Marie Nicolas Sylvestre Guillon

Marie Nicolas Sylvestre Guillon , French ecclesiastic, was born in Paris.He was librarian and almoner in the household of the princesse de Lamballe, and when in 1792 she was executed, he fled to the provinces, where under the name of Pastel he practised medicine.A man of facile conscience, he...

, an opponent of the Civil Constitution, without consulting the archbishop or the parish curé. The attitude of the archbishop caused great excitement in Paris, and the government had to take precautions to avoid a repetition of the riots which in the preceding February had led to the sacking of the church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois

Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois

The Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois is situated at 2, Place du Louvre, Paris 75001; the nearest Métro station is Louvre-Rivoli.Located at the center of Paris, by the Seine and near the Louvre, this former parish of the kings of France is generally regarded as the Church of the Louvre...

and the archiepiscopal palace. Grégoire's funeral was held at the church of the Abbaye-aux-Bois. The clergy absented themselves in obedience to the archbishop's orders, but mass was sung by the Abbé Grieu assisted by two clerics, the catafalque

Catafalque

A catafalque is a raised bier, soapbox, or similar platform, often movable, that is used to support the casket, coffin, or body of the deceased during a funeral or memorial service. Following a Roman Catholic Requiem Mass, a catafalque may be used to stand in place of the body at the Absolution of...

being decorated with the episcopal insignia. After the hearse set out from the church the horses were unyoked, and it was dragged by students to the cemetery of Montparnasse

Montparnasse

Montparnasse is an area of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail...

, the cortege being followed by a sympathetic crowd of some 20,000 people.

Works

Besides several political pamphlets, Grégoire was the author of:- De la littérature des nègres, ou Recherches sur leurs facultés intellectuelles, leurs qualités morales et leur littérature (1808)

- Histoire des sectes religieuses, depuis le commencement du siècle dernier jusqu'à l'époque actuelle (a vols., 1810)

- Essai historique sur les libertés de l'église gallicane (1818)

- De l'influence du Christianisme sur la condition des femmes (1821)

- Histoire des confesseurs des empereurs, des rois, et d'autres princes (1824)

- Histoire du manage des primes en France (1826).

- Grégoireana, ou résumé général de la conduite, des actions, et des écrits de M. le comte Henri Grégkoire, preceded by a biographical notice by Cousin d'Avalon, was published in 1821; and the Mémoires ... de Grégoire, with a biographical notice by H Carnot, appeared in 1837 (2 vols.).

Other references

- Rita Hermon-Belot, L'abbé Grégoire, la politique et la vérité, Paris : Éd. du Seuil, 2000

- Grégoire et la cause des noirs (1789–1831) : combats et projects, sous la dir. de Yves Bénot, Saint Denis [etc.], Société française d'histoire d'outre-mer [etc.], 2000.

- Henri Grégoire, De la Noblesse de la peau ou Du préjugé des blancs contre la couleur des Africains et celle de leurs descendants noirs et sang-mêlés (1826), Grenoble: Millon, 2002.

- Ruth F. Necheles, The Abbé Grégoire, 1787-1831: The odyssey of an egalitarian, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Pub. Corp., 1971.

- Joseph L. Sax, "Historic Preservation as a Public Duty: The Abbe Gregoire and the Origin of an Idea", Michigan Law Review, vol. 88, no. 5 (April 1990), pp. 1142–69.

- Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, The Abbé Grégoire and the French Revolution: The Making of Modern Universalism Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005

External links

- Full text online english translation of De la littérature des nègres from 1810 at the University of South CarolinaUniversity of South CarolinaThe University of South Carolina is a public, co-educational research university located in Columbia, South Carolina, United States, with 7 surrounding satellite campuses. Its historic campus covers over in downtown Columbia not far from the South Carolina State House...

Library's Digital Collections Page