High Court of Australia

Encyclopedia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy

and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review

over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia

and the parliaments of the States

, and interprets the Constitution of Australia

. The High Court is mandated by section 71 of the Constitution, which vests in it the judicial power

of the Commonwealth of Australia. The High Court was constituted by the Judiciary Act 1903

. The High Court of Australia is located in Canberra

, Australian Capital Territory

.

(cases which originate in the High Court) and appellate jurisdiction (appeals made to the High Court from other courts). The High Court is the court of final appeal for the whole of Australia with the ability to interpret the common law

for the whole of Australia, not just the state or territory in which the matter arose. This is unlike other high courts, such as the Supreme Court of the United States

(though US federal courts do have the ability to shape US federal common law

). As such, the court is able to develop the common law

consistently across all of the states and territories. This role, alongside its role in constitutional interpretation, is one of the court's most significant. As Sir Owen Dixon

said on his swearing in as Chief Justice of Australia

:

This broad array of jurisdiction has enabled the High Court to take a leading role in Australian law, and has contributed to a consistency and uniformity among the laws of the different states.

Section 75 of the Constitution confers original jurisdiction in regard to "all matters":

The conferral of original jurisdiction creates some problems for the High Court. For example, challenges against immigration-related decisions are often brought against an officer of the Commonwealth within the original jurisdiction of the High Court.

Section 76 provides that Parliament may confer original jurisdiction in relation to matters:

Constitutional matters, referred to in section 76(i), have been conferred to the High Court by section 30 of the Judiciary Act 1903

. However, the inclusion of constitutional matters in section 76, rather than section 75, means that the High Court’s original jurisdiction regarding constitutional matters could be removed. In practice, section 75(iii) (suing the Commonwealth) and section 75(iv) (conflicts between states) are broad enough that many constitutional matters would still be within jurisdiction. The original constitutional jurisdiction of the High Court is now well established: the Australian Law Reform Commission

has described the inclusion of constitutional matters in section 76 rather than section 75 as "an odd fact of history." The 1998 constitutional convention

recommended an amendment to the constitution to prevent the possibility of the jurisdiction being removed by Parliament. Failure to proceed on this issue suggests that it was considered highly unlikely that Parliament would ever take this step.

The requirement of "a matter" in section 75 and section 76 of the constitution means that a concrete issue must need to be resolved, and the High Court cannot give an advisory opinion.

, from any federal court or court exercising federal jurisdiction (such as the Federal Court of Australia

), and from decisions made by one or more Justices exercising the original jurisdiction of the court.

However, section 73 allows the appellate jurisdiction to be limited "with such exceptions and subject to such regulations as the Parliament prescribes". Parliament has prescribed a large limitation in section 35A of the Judiciary Act 1903

. This requires "special leave" to appeal. Special leave is granted only where a question of law is raised which is of public importance; or involves a conflict between courts; or "is in the interests of the administration of justice". Therefore, while the High Court is the final court of appeal it cannot be considered to be a general court of appeal. The decision as to whether to grant special leave to appeal is determined by one or more Justices of the High Court (in practice, a panel of 2 or 3 judges). That is, Court exercises the power to decide which appeal cases it will consider.

The issue of appeals from the High Court to the United Kingdom's Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The issue of appeals from the High Court to the United Kingdom's Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

was a significant one during the drafting of the Constitution, and it continued to be significant in the years after the court's creation. The final wording of section 74 prohibited appeals on constitutional matters involving disputes about the limits inter se

of Commonwealth or state powers, except where the High Court certified the appeal. It did so only once: in the case of Colonial Sugar Refining Co v Attorney-General (Commonwealth) (1912). After that case, in which the Privy Council refused to answer the constitutional questions put to it, the High Court never certified another inter se appeal. Indeed, in the case of Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd (No 2)

(1985), the court said that it would never again grant a certificate of appeal.

In general matters however, section 74 did not prevent the Privy Council from granting leave to appeal against the High Court's wishes, and the council did so often. In some cases, the council acknowledged that the Australian common law had developed differently from English law, and thus did not apply its own principles (for example, in Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v Uren (1967), or in Viro v The Queen (1978)), by using a legal fiction

which stated that different common law can apply to different circumstances. However, in other cases, the Privy Council enforced English decisions, overruling decisions by the High Court. In Parker v The Queen (1963), Chief Justice Sir Owen Dixon

led a unanimous judgment which rejected a precedent of the House of Lords

in DPP v Smith, saying that "I shall not depart from the law on this matter as we have long since laid it down in this Court and I think that Smith's case should not be used in Australia as authority at all"; the following year the Privy Council upheld an appeal, applying the House of Lords precedent.

Section 74 did provide that the parliament could make laws to prevent appeals to the council, and it did so, beginning in 1968, with the Privy Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968, which closed off all appeals to the Privy Council in matters involving federal legislation. In 1975, the Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 was passed, which had the effect of closing all routes of appeal from the High Court. Appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council are now only theoretically possible in inter se

matters if the High Court grants a certificate of appeal under section 74 of the Constitution. As noted above, the High Court indicated in 1985 it would not grant such a certificate in the future, and it is practically certain that all future High Courts will maintain this policy. In 1986, with the passing of the Australia Acts

by both the UK Parliament

and the Parliament of Australia

(with the ratification of the States

), appeals to the Privy Council from state Supreme Courts were closed off, leaving the High Court as the only avenue of appeal.

and Australia in 1976, in application of article 57 of the Constitution of Nauru

, the High Court of Australia is the ultimate court of appeal for the sovereign Republic of Nauru, formerly an Australian colony. Thus the High Court may hear appeals from the Supreme Court of Nauru

in both criminal and civil cases, with certain exceptions; in particular, no case pertaining to the Constitution of Nauru may be decided by the Australian court.

, which involved the great expense of physically travelling to London

. As such, some politicians in the colonies wanted to have a new court which could travel between the colonies hearing appeals.

Following Earl Grey's 1846 proposal for federation of the Australian colonies, an 1849 report from the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

suggested that a national court be created. In 1856, the then Governor of South Australia, Richard Graves MacDonnell

, suggested to the Government of South Australia

that they and the other colonies should consider establishing a court of appeal which would hear appeals from the Supreme Courts in each colony, and in 1860 the Parliament of South Australia

passed legislation encouraging MacDonnell to put forward the idea to his colleagues in the other colonies. However, only the Government of Victoria

seriously considered this proposal.

At an inter-colonial conference in 1870 in Melbourne

, Victoria

, the idea of an inter-colonial court was again raised, and subsequently a Royal Commission

was established in Victoria, to investigate options not only for establishing a court of appeal, but for unifying extradition

laws between the colonies and other similar matters. A draft bill establishing a court was put forward by the Commission, but it completely excluded appeals to the Privy Council, which reacted critically and prevented any serious attempts to implement the bill in London (before federation

, any laws affecting all the colonies would have to be passed by the British Imperial Parliament in London).

In 1880, another inter-colonial conference was convened, which proposed the establishment of an Australasian Court of Appeal. This conference was more firmly focused on having an Australian court. Another draft bill was produced, providing that judges from the colonial Supreme Courts would serve one-year terms on the new court, with one judge from each colony at a given time. New Zealand, which was at the time also considering joining the Australian colonies in federation, was also to be a participant in the new court. However, the proposal retained appeals from colonial Supreme Courts to the Privy Council, which some of the colonies disputed, and the bill was eventually abandoned.

The Constitutional Conventions

The Constitutional Conventions

of the 1890s, which met to draft an Australian Constitution

, also raised the idea of a federal Supreme Court. Initial proposals at a conference in Melbourne

in February 1890 led to a convention in Sydney

in March and April 1891, which produced a draft constitution. The draft included the creation of a Supreme Court of Australia, which would not only interpret the Constitution, like the United States Supreme Court, but also would be a court of appeal from the state Supreme Courts. The draft effectively removed appeals to the Privy Council, allowing them only if the British monarch gave leave to appeal and not allowing appeals at all in constitutional matters.

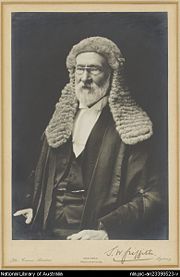

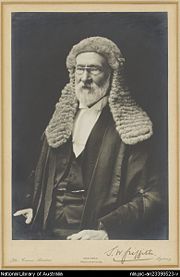

This draft was largely the work of Sir Samuel Griffith

, then the Premier of Queensland, later Chief Justice of Queensland and the first Chief Justice of Australia

. Other significant contributors to the judicial clauses in the draft included Attorney-General of Tasmania Andrew Inglis Clark

, who had prepared his own constitution prior to the convention. Inglis Clark's most significant contribution was to give the court its own constitutional authority, ensuring the separation of powers

; the original formulation from Griffith, Edmund Barton

and Charles Kingston

provided only that the parliament could establish a court.

At the later conventions, in Adelaide

At the later conventions, in Adelaide

in 1897, in Sydney later the same year and in Melbourne in early 1898, there were changes to the earlier draft. In Adelaide, the name of the court was changed from Supreme Court of Australia to High Court of Australia. Many people also opposed the new court completely replacing the Privy Council: many large businesses, particularly those which were subsidiaries of British companies or regularly traded with the United Kingdom, preferred for business reasons to keep the colonies under the unified jurisdiction of the British courts, and petitioned the conventions to that effect. Other arguments posited against removing Privy Council appeals were that Australian judges were of a poorer quality than English ones, and that without the Council's oversight, the law in the colonies risked becoming different from English law. Some politicians, such as Sir George Dibbs

, supported the petitioners, but others, including Alfred Deakin

, supported the design of the court as it was. Inglis Clark took the view that the possibility of divergence was a good thing, for the law could adapt appropriately to Australian circumstances. Despite the debate, the portions of the draft dealing with the court remained largely unchanged, as the delegates focused on different matters.

After the draft had been approved by the electors of the colonies, it was taken to London in 1899, for the assent of the British Imperial Parliament. However the issue of Privy Council appeals remained a sticking point with a number of Australian and British politicians, including the Secretary of State for the Colonies

, Joseph Chamberlain

, the Chief Justice of South Australia, Sir Samuel Way

, and the Chief Justice of Queensland, Sir Samuel Griffith

. Indeed, in October 1899, Griffith made representations to Chamberlain soliciting suggestions from British ministers for alterations to the draft, and offering some alterations of his own. Indeed, such was the effect of these and other representations that Chamberlain called for delegates from the colonies to come to London to assist with the approval process, with a view to their approving any alterations that the British government might see fit to make; delegates were sent, including Deakin, Barton and Charles Kingston

, although they were under instructions that they would never agree to changes.

After intense lobbying both in Australia and in the United Kingdom, the Imperial Parliament finally approved the draft constitution, albeit with an altered section 74, which represented a compromise between the two sides: there would be a general right of appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council, except that the Parliament of Australia

would be able to make laws restricting this avenue, and also that appeals in inter se matters (matters concerning the boundary between and limits of the powers of the Commonwealth and the powers of the states) were not as of right, but had to be certified by the High Court.

to make laws about the structure and procedure of the court. Some of the members of the First Parliament, including Sir John Quick

, then one of the leading legal experts in Australia, opposed legislation to set up the court. Even H. B. Higgins

, who was himself later appointed to the court, objected to setting it up, on the grounds that it would be impotent while Privy Council appeals remained, and that in any event there was not enough work for a federal court to make it viable.

In 1902, the then Attorney-General

Alfred Deakin introduced the Judiciary Bill 1902 into the parliament. Although Deakin and Griffith had produced a draft bill as early as February 1901, it was continually delayed by opponents in the parliament, and the success of the bill is generally attributed to Deakin's passion and effort in pushing the bill through the parliament despite this opposition. Deakin had proposed that the court be composed of five judges, specially selected to the court; opponents instead proposed that the court should be made up of state Supreme Court justices, taking turns to sit on the High Court on a rotation basis, as had been mooted at the Constitutional Conventions a decade before. Deakin eventually negotiated amendments with the opposition

, reducing the number of judges from five to three, and eliminating financial benefits such as pensions.

At one point, Deakin even threatened to resign as Attorney-General due to the difficulties he faced. In what is now a famous speech, Deakin gave a second reading

to the House of Representatives

, lasting three and a half hours, in which he declared:

Deakin's friend, painter Tom Roberts

, who viewed the speech from the public gallery, declared it Deakin's "magnum opus". The Judiciary Act 1903

was finally passed on 25 August 1903, and the first three justices, Chief Justice

Sir Samuel Griffith

and Justices Sir Edmund Barton

and Richard O'Connor were appointed on 5 October of that year. On 6 October, the court held its first sitting in the Banco Court in the Supreme Court of Victoria

.

, the court continued to use that court until 1928, when a dedicated courtroom was built in Little Bourke Street

, next to the Supreme Court of Victoria

, which provided the court's Melbourne sitting place and housed the court's principal registry

until 1980. The court also sat regularly in Sydney

, where it originally shared space in the Criminal Courts in the suburb of Darlinghurst

, before a dedicated courtroom was constructed next door in 1923.

The court travelled to other cities across the country, where it did not have any facilities of its own, but used facilities of the Supreme Court in each city. Alfred Deakin had envisaged that the court would sit in many different locations, so as to truly be a federal court. Shortly after the court's creation, Chief Justice Griffith established a schedule for sittings in state capitals: Hobart

, Tasmania

in February, Brisbane

, Queensland

in June, Perth

, Western Australia

in September and Adelaide

, South Australia

in October; it is said that Griffith established this schedule because those were the times of year he found the weather most pleasant in each city. The tradition remains to this day, although most of the court's sittings are now conducted in Canberra

.

Sittings were dependent on the caseload, and to this day sittings in Hobart occur only once every few years. There are annual sittings in Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane for up to a week each. During the Great Depression

, sittings outside of Melbourne and Sydney were suspended in order to reduce costs.

During World War II

, the court faced a period of change. The Chief Justice, Sir John Latham

, served from 1940 to 1941 as Australia's first ambassador to Japan

, although his activities in this role were limited by the mutual assistance pact that Japan had entered into with the Axis powers

before he could arrive in Tokyo

, and were curtailed by the commencement of the Pacific War

. Justice Sir Owen Dixon

was also absent for several years, while he served as Australia's minister to the United States

in Washington

. Sir George Rich

was Acting Chief Justice in Latham's absence. There were many difficult cases concerning the federal government

's use of the defence power during the war.

, the court's workload continued to grow, particularly from the 1960s onwards, putting pressures on the court. Sir Garfield Barwick

, who was Attorney-General

from 1958 to 1964, and from then till 1981 Chief Justice

, proposed that more federal courts be established, as permitted under the Constitution. In 1976 the Federal Court of Australia

was established, with a general federal jurisdiction, and in more recent years the Family Court

and Federal Magistrates Court have been set up to reduce the court's workload in specific areas.

Robert Menzies

had established a plan to develop Canberra, and construct other important national buildings. In 1959, a plan featured a new building for the High Court on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin

, next to the location for the new Parliament House

, and the National Library of Australia

. This plan was abandoned in 1968, and the location of the Parliament was moved, later settling on the present site on Capital Hill.

In March 1968, the government announced that the court would move to Canberra. In 1972 an international competition was held attracting 158 entries. In 1973 the firm of Edwards Madigan Torzillo Briggs was declared the winner of the two-stage competition. Architect Chris Kringas was the Principal Designer and Director in charge of the design team that included Feiko Bouman and Rod Lawrence. In 1975, only one month before construction began, Kringas died aged 38. Following his death, Architect Hans Marelli and Colin Madigan

supervised the construction of the design.

Construction began in April 1975 on the shore of Lake Burley Griffin, in the Parliamentary Triangle. The site is just to the east of the axis running between Capital Hill and the Australian War Memorial

. The High Court building houses three courtrooms, Justices' chambers, and the Court's main registry, library, and corporate services facilities. It is an unusual and distinctive structure, built in the brutalist style, and features an immense public atrium with a 24 metre high roof. The neighbouring National Gallery was also designed by the firm of Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Briggs. There are similarities between the two buildings in material and style but significant differences in architectural form and spatial concept. The building was completed in 1980, and the majority of the court's sittings have been held in Canberra since then.

The High Court and National Gallery Precinct were added to the Australian National Heritage List

in November 2007.

of the time.

As the first High Court, the court under Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith

As the first High Court, the court under Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith

had to establish its position as a new court of appeal for the whole of Australia, and had to develop a new body of principle for interpreting the Constitution of Australia

and federal legislation. Griffith himself was very much the dominant influence on the court in its early years, but after the appointment of Sir Isaac Isaacs

and H. B. Higgins

in 1906, and the death of foundation Justice Richard O'Connor

, Griffith's influence began to decline.

The court was keen to establish its position at the top of the Australian court hierarchy

. In Deakin v Webb (1904) Griffith criticised the Supreme Court of Victoria

for following a Privy Council

decision about the Constitution of Canada

, rather than following the High Court's own decision on the Australian Constitution.

In Australian constitutional law

, the early decisions of the court were influenced by United States constitutional law

. In the case of D'Emden v Pedder

(1904), which involved the application of Tasmania

n stamp duty

to a federal official's salary

, the court adopted the doctrine of implied immunity of instrumentalities which had been established in the United States Supreme Court

case of McCulloch v. Maryland

(1803). That doctrine established that any attempt by the federal government to interfere with the legislative or executive power of the states

was invalid, and vice versa. Accompanying that doctrine was the doctrine of reserved State powers

, which was based on the principle that the powers of the federal parliament

should be interpreted narrowly, to avoid intruding on areas of power traditionally exercise by the state parliaments. The concept was developed in such cases as Peterswald v Bartley

(1904), R v Barger

(1908) and the Union Label case (1908).

Together the two doctrines helped smooth the transition to a federal system of government, and "by preserving a balance between the constituent elements of the Australian federation, probably conformed to community sentiment, which at that stage was by no means adjusted to the exercise of central power." The court had a generally conservative view of the Constitution, taking narrow interpretations of section 116 (which guarantees religious freedom) and section 117 (which prevents discrimination on the basis of someone's state of origin), interpretations that were to last well into the 1980s.

Two of the original judges of the Court, Griffith and Sir Edmund Barton

, were frequently consulted by governors-general, including on the exercise of the reserve powers. This practice of consultation has continued from time to time since.

(later Sir Adrian) became Chief Justice on 18 October 1919, and less than three months later, foundation Justice Sir Edmund Barton

died, leaving no original members. The most significant case of the era was the Engineers case (1920), decided at the beginning of Knox's term. In that case, the doctrines of reserved State powers and implied immunity of instrumentalities were both overturned, and the court entered a new era of constitutional interpretation in which the focus would fall almost exclusively on the text of the Constitution, and in which the powers of the federal parliament

would gain increasing importance.

Knox was knighted in 1921, the only Chief Justice to be first knighted during his term. Some of the Knox court's early work related to the aftermath of World War I

. In Roche v Kronheimer (1921), the court upheld federal legislation which allowed for the making of regulations to implement Australia's obligations under the Treaty of Versailles

. The majority decided the case on the defence power

, but Higgins decided it on the external affairs power

, the first case to decide that the external affairs power could be used to implement an international treaty in Australia.

Sir Isaac Isaacs

was Chief Justice for only forty-two weeks, before leaving the court to be appointed Governor-General of Australia

. Isaacs was ill for much of his term as Chief Justice, and few significant cases were decided under his formal leadership; rather, his best years were under Knox, where he was the most senior puisne

Justice and led the court in many decisions.

Sir Frank Gavan Duffy

was Chief Justice for four years beginning in 1931, although he was already 78 when appointed to the position and did not exert much influence, given that (excluding single-Justice cases) he participated in only 40 per cent of cases in that time, and regularly gave short judgments or joint judgments with other Justices. In the context of the Great Depression

, the court was reduced to six Justices, resulting in many tied decisions which have no lasting value as precedent

.

During this time, the court did decide several important cases, including Attorney-General (New South Wales) v Trethowan (1931), which considered Premier of New South Wales Jack Lang

's attempt to abolish the New South Wales Legislative Council

, and the First State Garnishee case (1932), which upheld federal legislation compelling the Lang government to repay its loans. Much of the court's other work related to legislation passed in response to the Depression.

The court under Chief Justice Sir John Latham, who came to the office in 1935, was punctuated by World War II

The court under Chief Justice Sir John Latham, who came to the office in 1935, was punctuated by World War II

. Although it dealt with cases in other areas, its most important and lasting work related to wartime legislation, and the transition back to peace following the war. The court upheld much legislation under the defence power

, interpreting it broadly wherever there was a connection to defence purposes, in cases such as Andrews v Howell (1941) and de Mestre v Chisholm (1944). In general, the Curtin

Labor

government was rarely successfully challenged, the court recognising the necessity that the defence power permit the federal government to govern strongly. The court also allowed the federal government to institute a national income tax

scheme in the First Uniform Tax case

(1942), and upheld legislation allowing the proclamation of the pacifist Jehovah's Witnesses

religion as a subversive organisation, in the Jehovah's Witnesses case

(1943).

The court reined in the wide scope of the defence power after the war, allowing for a transitional period. It struck down several key planks of the Chifley

Labor government's reconstruction program, notably an attempt to nationalise

the banks in the Bank Nationalisation case

(1948), and an attempt to establish a comprehensive medical benefits scheme in the First Pharmaceutical Benefits case

(1945). However the court also famously struck down Menzies

Liberal

government legislation banning the Communist Party of Australia

in the Communist Party case

(1951), Latham's last major case.

Apart from the wartime cases, the Latham court also developed the criminal

defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact, for example in Proudman v Dayman (1941). It also paved the way for the development of the external affairs power

by upholding the implementation of an air navigation treaty in R v Burgess; Ex parte Henry

(1936).

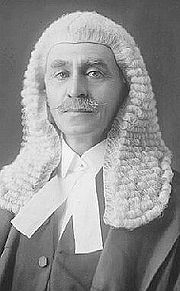

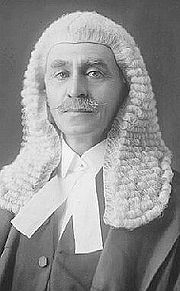

Under Chief Justice Sir Owen Dixon

Under Chief Justice Sir Owen Dixon

, who was elevated to that role in 1952 after 23 years as a puisne

Justice, the court enjoyed its most successful period, with British

judge, Master of the Rolls

Lord Denning, describing the time as the court's "Golden Age". Dixon, widely regarded as Australia's greatest judge, had a commanding personal and legal influence over the court in this time, measurable in the rise in joint judgments (many of which were led by Dixon) and good relations between the Justices.

While there were fewer cases which tested the limits of federal power, which was probably due to the Menzies government which was firmly entrenched in its conservative phase throughout Dixon's tenure, the court did decide several important constitutional cases. Dixon led the court in firmly establishing the separation of powers

for the judiciary

in the Boilermakers' case

(1956), and the court also upheld the continuing existence of the federal government's income tax scheme in the Second Uniform Tax case

(1957).

During Dixon's time as Chief Justice, the court came to adopt several of the views that Dixon had advanced in minority opinions in years prior. In several cases, the court upheld Dixon's interpretation of section 92 of the Australian Constitution (one of the most troublesome sections of the Constitution), which he regarded as guaranteeing a constitutional right to engage in interstate trade, subject to reasonable regulation. It also followed Dixon's interpretation of section 90 (which prohibits the states from exacting duties of excise

), although both these interpretations were ultimately abandoned many years later.

came to the court as Chief Justice in 1964. A significant decision of the Barwick court marked the beginning of the modern interpretation of the corporations power

, which had been interpreted narrowly since 1909. The Concrete Pipes case

(1971) established that the federal parliament could exercise the power to regulate at least the trading activities of corporations, whereas earlier interpretations had allowed only the regulation of conduct or transactions with the public.

The court decided many other significant constitutional cases, including the Seas and Submerged Lands case (1975), upholding legislation asserting sovereignty over the territorial sea; the First (1975) and Second (1977) Territory Senators cases, which concerned whether legislation allowing for the mainland territories

to be represented in the Parliament of Australia

was valid; and Russell v Russell (1976), which concerned the validity of the Family Law Act 1975

. The court also decided several cases relating to the historic 1974 joint sitting

of the Parliament of Australia, including Cormack v Cope (1974) and the Petroleum and Minerals Authority case (1975).

The Barwick court decided several infamous cases on tax avoidance and tax evasion

, almost always deciding against the taxation office. Led by Barwick himself in most judgments, the court distinguished between avoidance (legitimately minimising one's tax obligations) and evasion (illegally evading obligations). The decisions effectively nullified the anti-avoidance legislation, and led to the proliferation of avoidance schemes in the 1970s, a result which drew much criticism upon the court.

Sir Harry Gibbs

Sir Harry Gibbs

was appointed as Chief Justice in 1981. Under his leadership, the court moved away from the legalism and conservative traditions which had characterised the Dixon and Barwick courts.

The Gibbs court made several important decisions in Australian constitutional law

. It allowed the Federal Parliament to make very wide use of the external affairs power

, by holding that this power could be used to implement treaties

into domestic law with very few justiciable limits. In Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen

(1982) four judges to three upheld the validity of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975

, although no single view had majority support. However, in the Tasmanian Dams case

(1983), a majority of the court upheld federal environmental legislation under the power.

The court also adopted a more expansive interpretation of the corporations power

. In the Actors Equity case (1982), the court upheld regulations which, although they did not directly regulate corporation

s, indirectly protected corporations. In the Tasmanian Dams case, the court indicated that it would interpret the power to uphold legislation regulating the non-trading activities of corporations, although it did not decide the case on that basis. The external affairs power and the corporations power have both been increasingly relied on by the federal government to extend its authority in recent years.

In administrative law

, the court expanded on the doctrines of natural justice

and procedural fairness

in Kioa v West

(1985). Although Gibbs himself dissented on those points, he did decide that executive decision makers were obliged to take humanitarian

principles into consideration. Outside of specific areas of law, the court was also involved in several cases of public significance, including the Chamberlain case (1984), concerning Lindy Chamberlain

, and A v Hayden (1984), concerning the botched ASIS

exercise at the Sheraton Hotel in Melbourne.

Sir Anthony Mason became Chief Justice in 1987. The Mason court was very stable with only one change in the bench in its eight years, the appointment of Michael McHugh

Sir Anthony Mason became Chief Justice in 1987. The Mason court was very stable with only one change in the bench in its eight years, the appointment of Michael McHugh

after Sir Ronald Wilson

's retirement. The court under Mason was widely regarded as the most liberal bench in the court's history.

The Mason court made many important decisions in all areas of Australian law. One of its first major cases was Cole v Whitfield

(1988), concerning the troublesome section 92 of the Australian Constitution, which had been interpreted inconsistently and confusingly since the beginning of the court. For the first time, the court referred to historical materials such as the debates of the Constitutional Conventions

in order to ascertain the purpose of the section, and the unanimous decision indicated "a willingness to overturn established doctrines and precedents perceived to be no longer working", a trend which typified the Mason court.

The most popularly significant case decided by the Mason court was the Mabo case (1992), in which the court found that the common law

was capable of recognising native title

. The decision was one of the High Court's most controversial of all time, and represented the tendency of the Mason court to receive "high praise and stringent criticism in equal measure." Other controversial cases included the War Crimes Act case

(1991), regarding the validity of the War Crimes Act 1945; Dietrich v The Queen

(1992), in which the court found that a lack of legal representation in a serious criminal case can result in an unfair trial; Sykes v Cleary (1992), regarding the disputed election of Phil Cleary

; and Teoh's case

(1995), in which the court held that ratification

of a treaty by the executive could create a legitimate expectation that members of the executive would act in accordance with that treaty.

The court developed the concept of implied human rights in the Constitution, in cases such as Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth

(1992), Nationwide News v Wills (1992) and Theophanous v Herald and Weekly Times (1994), in which the court recognised an implied freedom of political communication arising from the nature of the Constitution in laying out a system of representative government.

In other areas of law, the court developed doctrines of equity in relation to commercial law and contract law

, in cases such as Waltons Stores v Maher (1988) and Trident General Insurance v McNiece (1988), and made significant developments in tort law

, in cases such as Rogers v Whitaker (1992) and Burnie Port Authority v General Jones (1994).

Sir Gerald Brennan

Sir Gerald Brennan

succeeded Mason in 1995. In contrast to the previous court, the Brennan court had many changes in its membership despite being only three years long. The court decided many significant cases.

In Ha v New South Wales

(1997) the court invalidated a New South Wales

tobacco

licensing scheme, reining in the licensing scheme exception to the prohibition states levying excise

duties, contained in section 90 of the Australian Constitution. While it did not overturn previous cases in which schemes had been upheld, it did emphasise that the states could not stray too far from the constitutional framework.

The Brennan court made a number of significant decisions in relation to the judiciary of Australia

. In Grollo v Palmer (1995) and Wilson v Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs (1998), the court developed the persona designata

doctrine, and in Kable v DPP (1997), the court rejected attempts by the Parliament of New South Wales

to establish a system of preventative detention, and found that the states do not have unlimited ability to regulate their courts, given the place of the courts in the Australian court hierarchy

.

The court decided several cases relating to the implied freedom of political communication developed by the Mason court, notably Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation

(1997) and Levy v Victoria (1997). It also decided several native title cases, including the controversial Wik case

(1996).

(the first Chief Justice not to be knighted) was appointed Chief Justice in 1998. The court under Gleeson's leadership was generally regarded as more conservative than under Mason or Brennan, favouring legalism in the tradition of the Dixon and Barwick courts. In many cases the Gleeson court focused heavily on the text itself when interpreting the Constitution or a particular statute. In the Cross-vesting case

(1999), the court struck down legislation vesting certain areas of federal jurisdiction in the Supreme Courts of the states. In Al-Kateb v Godwin

(2004) a majority of the court applied a narrow interpretation of the Migration Act 1958, finding that it permitted executively

-imposed indefinite detention of stateless persons.

However, the court did not entirely shy away from principle and public policy in its decisions. In Egan v Willis (1998), the court supported the New South Wales Legislative Council

's ability to suspend the Treasurer when he failed to produce documents before the Council, emphasising the purpose of the ability in facilitating responsible government

. In Sue v Hill

(1999), the court recognised Australia's emergence as a sovereign independent nation, finding that the United Kingdom was a "foreign power".

The Gleeson court decided a number of important native title cases, including Yanner v Eaton (1999), Western Australia v Ward (2002) and the Yorta Yorta case (2002). In tort law

, the court's significant decisions include Perre v Apand Pty Ltd (1999), concerning negligence

actions where there is only pure economic loss as opposed to physical or mental injury, Dow Jones v Gutnick

(2002), regarding defamation on the Internet

, and Cattanach v Melchior

(2003), a wrongful life

case involving a healthy child. In criminal law

, the court in R v Tang (2008) upheld slavery

convictions against the owner of a brothel who had held several women in debt bondage

after they had been trafficked

to Australia.

Perhaps the Gleeson court's most significant case was amongst its later ones. In the WorkChoices case

(2006), in which the court finally explicitly accepted a wide reading of the corporations power

, after years of gradual expansion following the Concrete Pipes case

(1971).

, was appointed in September 2008. The first decision handed down by the French Court was Lujans v Yarrabee Coal Company Pty Ltd (2008), a case dealing with a motor vehicle accident. One of the most notable judgments handed down by the French Court was Pape v Commissioner of Taxation

(2009), a Constitutional law case concerning the existence of the Commonwealth's so-called "appropriation power", and the scope of its executive and taxation powers.

and six other (puisne

) Justices. The current Justices are:

The first three justices of the High Court were:

There were a number of possible candidates for the first bench of the High Court. In addition to the eventual appointees, Griffith, Barton and O'Connor, names which had been mentioned in the press included two future Justices of the court, Henry Higgins and Isaac Isaacs

, along with Andrew Inglis Clark

, Sir John Downer

, Sir Josiah Symon

and George Wise

. (Crucially, all of the above had previously served as politicians, with only Griffith and Inglis Clark possessing both political and judicial experience). Barton and O'Connor were both members of the federal parliament, and both from the government benches; indeed Barton was Prime Minister

. Each of the eventual appointees had participated in the drafting of the Constitution, and had intimate knowledge of it. All three were described as conservative, and their jurisprudence was very much influenced by English law, and in relation to the Constitution, by United States law.

In 1906, at the request of the Justices, two more seats were added to the bench, with Isaacs and Higgins the appointees. After O'Connor's death in 1912, an amendment to the Judiciary Act 1903

expanded the bench to seven. For most of 1930 two seats were left vacant, due to monetary constraints placed on the court by the Depression. The economic downturn had also led to a reduction in litigation, and consequently less work for the court. After Sir Isaac Isaacs retired in 1931, his seat was left empty, and in 1933 an amendment to the Judiciary Act officially reduced the number of seats to six. However, this led to some decisions being split three-all. With the appointment of William Webb in 1946, the number of seats returned to seven, and since then the court has had a full complement of seven Justices. there have been 46 Justices, eleven of whom have been Chief Justice

. Current Justices Susan Crennan

and Susan Kiefel

are the second and third women to sit on the bench, after Justice Mary Gaudron

. With Virginia Bell

having taken office in February 2009, there are three women sitting concurrently on the bench, alongside four men.

More than half of the Justices, twenty-four, have been residents of New South Wales

(with twenty-three of these graduates of Sydney Law School

). Thirteen were from Victoria

, six from Queensland

and three from Western Australia

. No Justices have been residents of South Australia

or Tasmania

, or any of the territories. The majority of the justices have been from Protestant backgrounds, with a smaller number from Catholic

backgrounds. Sir Isaac Isaacs

was of Polish/Jewish background, the only representative of any other faith. He also remains the only High Court Justice from a non Anglo-Celtic

background. Michael Kirby was the first openly gay justice in the history of the Court; his replacement Virginia Bell

is the first lesbian, who has been an active campaigner for gay and lesbian rights and was one of the participants in the first Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras

in 1978.

Almost every single judge on the High Court has taken silk as a QC

or KC before appointment. The exceptions are: Justice Sir Hayden Starke

(although he refused to take silk), Justices Sir Edward McTiernan

, Sir William Webb, Sir Cyril Walsh

, Michael Kirby and now Chief Justice Robert French

.

Since the retirement of Ian Callinan

in 2007, every justice of the High Court, for the first time in its history, has had prior judicial experience (serving on state Supreme Courts or the Federal Court of Australia

. Although 13 justices of the Court had previously served in state, colonial or federal Parliaments, no parliamentarian has been appointed to the Court since Lionel Murphy

's appointment in 1975.

. In practice, appointees are nominated by the Prime Minister

, on advice from the Cabinet, particularly from the Attorney-General of Australia

. For example, four Justices were appointed while Andrew Fisher

was Prime Minister, but it was largely on Attorney-General Billy Hughes

' authority that the candidates were chosen. Since 1979, the Attorney-General has been required by section 6 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979 to consult with the Attorneys-General of the states and territories of Australia

about appointments to the court. The process was first used in relation to the appointment of Justice Wilson

, and has been generally successful, despite the occasional criticism that the states merely have a consultative, rather than a determinative, role in the selection process.

There are no qualifications for Justices in the Constitution

(other than that they must be under the retirement age of 70). The High Court of Australia Act requires that appointees have been a judge of a federal, state or territory court

, or that they have been enrolled as a legal practitioner for at least five years, with either the High Court itself or with a state or territory Supreme Court. There are no other formal requirements.

The appointment process stands in stark contrast with the highly public selection and confirmation process for justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

. While there are people who are critical of the secrecy of the process, and who advocate a more public method for appointments, there are relatively few who dispute the quality of appointees. Although three of the Chief Justices (Sir Adrian Knox

, Sir John Latham

and Sir Garfield Barwick

) were conservative politicians at the time of their appointment, and were appointed by conservative governments, their political views are not considered to have interfered with their performance on the court, and their talent is rarely questioned. However, there is frequent criticism of Barwick's intervention in the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, when he gave advice to Governor-General

Sir John Kerr. On the other side of politics, Labor

politicians H. V. Evatt

, Sir Edward McTiernan

, and Lionel Murphy

were also appointed to the High Court; Murphy's appointment was controversial at the time and his reputation was gravely damaged in 1985 by charges that he had attempted to pervert the course of justice, although he was eventually acquitted.

Australian court hierarchy

There are two streams within the hierarchy of Australian courts, the federal stream and the state and territory stream. While the federal courts and the court systems in each state and territory are separate, the High Court of Australia remains the ultimate court of appeal for the Australian...

and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review

Judicial review

Judicial review is the doctrine under which legislative and executive actions are subject to review by the judiciary. Specific courts with judicial review power must annul the acts of the state when it finds them incompatible with a higher authority...

over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia

Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

and the parliaments of the States

States and territories of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a union of six states and various territories. The Australian mainland is made up of five states and three territories, with the sixth state of Tasmania being made up of islands. In addition there are six island territories, known as external territories, and a...

, and interprets the Constitution of Australia

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

. The High Court is mandated by section 71 of the Constitution, which vests in it the judicial power

Judiciary

The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary also provides a mechanism for the resolution of disputes...

of the Commonwealth of Australia. The High Court was constituted by the Judiciary Act 1903

Judiciary Act 1903

The Judiciary Act 1903 regulates the structure of the Australian judicial system and invests federal Australian courts with jurisdiction. Its passage, on 25 August 1903, established the High Court of Australia...

. The High Court of Australia is located in Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

, Australian Capital Territory

Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory, often abbreviated ACT, is the capital territory of the Commonwealth of Australia and is the smallest self-governing internal territory...

.

Role of the court

The High Court exercises both original jurisdictionJurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

(cases which originate in the High Court) and appellate jurisdiction (appeals made to the High Court from other courts). The High Court is the court of final appeal for the whole of Australia with the ability to interpret the common law

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

for the whole of Australia, not just the state or territory in which the matter arose. This is unlike other high courts, such as the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

(though US federal courts do have the ability to shape US federal common law

Federal common law

Federal common law is a term of United States law used to describe common law that is developed by the federal courts, instead of by the courts of the various states...

). As such, the court is able to develop the common law

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

consistently across all of the states and territories. This role, alongside its role in constitutional interpretation, is one of the court's most significant. As Sir Owen Dixon

Owen Dixon

Sir Owen Dixon, OM, GCMG, KC Australian judge and diplomat, was the sixth Chief Justice of Australia. A justice of the High Court for thirty-five years, Dixon was one of the leading jurists in the English-speaking world and is widely regarded as Australia's greatest ever jurist.-Education:Dixon...

said on his swearing in as Chief Justice of Australia

Chief Justice of Australia

The Chief Justice of Australia is the informal title for the presiding justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia...

:

"The High Court's jurisdiction is divided in its exercise between constitutional and federal cases which loom so largely in the public eye, and the great body of litigation between man and man, or even man and government, which has nothing to do with the Constitution, and which is the principal preoccupation of the court."

This broad array of jurisdiction has enabled the High Court to take a leading role in Australian law, and has contributed to a consistency and uniformity among the laws of the different states.

Original jurisdiction

The original jurisdiction of the High Court refers to matters which are originally heard in the High Court. The Constitution confers actual (section 75) and potential (section 76) original jurisdiction.Section 75 of the Constitution confers original jurisdiction in regard to "all matters":

- (i) arising under any treaty

- (ii) affecting consuls or other representatives of other countries

- (iii) in which the Commonwealth, or a person suing or being sued on behalf of the Commonwealth, is a party

- (iv) between States, or between residents of different States, or between a State and a resident of another State

- (v) in which a writ of mandamusMandamusA writ of mandamus or mandamus , or sometimes mandate, is the name of one of the prerogative writs in the common law, and is "issued by a superior court to compel a lower court or a government officer to perform mandatory or purely ministerial duties correctly".Mandamus is a judicial remedy which...

or prohibitionProhibition (writ)A writ of prohibition is a writ directing a subordinate to stop doing something the law prohibits. In practice, the Court directs the Clerk to issue the Writ, and directs the Sheriff to serve it on the subordinate, and the Clerk prepares the Writ and gives it to the Sheriff, who serves it.This...

or an injunctionInjunctionAn injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a court order that requires a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. A party that fails to comply with an injunction faces criminal or civil penalties and may have to pay damages or accept sanctions...

is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth.

The conferral of original jurisdiction creates some problems for the High Court. For example, challenges against immigration-related decisions are often brought against an officer of the Commonwealth within the original jurisdiction of the High Court.

Section 76 provides that Parliament may confer original jurisdiction in relation to matters:

- (i) arising under the constitution or involving its interpretation

- (ii) arising under any laws made by the Parliament

- (iii) of admiraltyAdmiralty lawAdmiralty law is a distinct body of law which governs maritime questions and offenses. It is a body of both domestic law governing maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between private entities which operate vessels on the oceans...

and maritime jurisdiction - (iv) relating to the same subject-matter claimed under the laws of different states.

Constitutional matters, referred to in section 76(i), have been conferred to the High Court by section 30 of the Judiciary Act 1903

Judiciary Act 1903

The Judiciary Act 1903 regulates the structure of the Australian judicial system and invests federal Australian courts with jurisdiction. Its passage, on 25 August 1903, established the High Court of Australia...

. However, the inclusion of constitutional matters in section 76, rather than section 75, means that the High Court’s original jurisdiction regarding constitutional matters could be removed. In practice, section 75(iii) (suing the Commonwealth) and section 75(iv) (conflicts between states) are broad enough that many constitutional matters would still be within jurisdiction. The original constitutional jurisdiction of the High Court is now well established: the Australian Law Reform Commission

Australian Law Reform Commission

The Australian Law Reform Commission is an Australian independent statutory body established to conduct reviews into the law of Australia and advocate options for law reform...

has described the inclusion of constitutional matters in section 76 rather than section 75 as "an odd fact of history." The 1998 constitutional convention

Constitutional Convention (Australia)

In Australian history, the term Constitutional Convention refers to four distinct gatherings.-1891 convention:The 1891 Constitutional Convention was held in Sydney in March 1891 to consider a draft Constitution for the proposed federation of the British colonies in Australia and New Zealand. There...

recommended an amendment to the constitution to prevent the possibility of the jurisdiction being removed by Parliament. Failure to proceed on this issue suggests that it was considered highly unlikely that Parliament would ever take this step.

The requirement of "a matter" in section 75 and section 76 of the constitution means that a concrete issue must need to be resolved, and the High Court cannot give an advisory opinion.

Appellate jurisdiction

The High Court's appellate jurisdiction is defined under Section 73 of the Constitution. The High Court can hear appeals from the Supreme Courts of the StatesStates and territories of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a union of six states and various territories. The Australian mainland is made up of five states and three territories, with the sixth state of Tasmania being made up of islands. In addition there are six island territories, known as external territories, and a...

, from any federal court or court exercising federal jurisdiction (such as the Federal Court of Australia

Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia is an Australian superior court of record which has jurisdiction to deal with most civil disputes governed by federal law , along with some summary criminal matters. Cases are heard at first instance by single Judges...

), and from decisions made by one or more Justices exercising the original jurisdiction of the court.

However, section 73 allows the appellate jurisdiction to be limited "with such exceptions and subject to such regulations as the Parliament prescribes". Parliament has prescribed a large limitation in section 35A of the Judiciary Act 1903

Judiciary Act 1903

The Judiciary Act 1903 regulates the structure of the Australian judicial system and invests federal Australian courts with jurisdiction. Its passage, on 25 August 1903, established the High Court of Australia...

. This requires "special leave" to appeal. Special leave is granted only where a question of law is raised which is of public importance; or involves a conflict between courts; or "is in the interests of the administration of justice". Therefore, while the High Court is the final court of appeal it cannot be considered to be a general court of appeal. The decision as to whether to grant special leave to appeal is determined by one or more Justices of the High Court (in practice, a panel of 2 or 3 judges). That is, Court exercises the power to decide which appeal cases it will consider.

The High Court and the Privy Council

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is one of the highest courts in the United Kingdom. Established by the Judicial Committee Act 1833 to hear appeals formerly heard by the King in Council The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is one of the highest courts in the United...

was a significant one during the drafting of the Constitution, and it continued to be significant in the years after the court's creation. The final wording of section 74 prohibited appeals on constitutional matters involving disputes about the limits inter se

Inter se

Inter se is a Legal Latin phrase meaning "between or amongst themselves". For example;In Australian constitutional law, it refers to matters concerning a dispute between the Commonwealth and one or more of the States concerning the extents of their respective powers....

of Commonwealth or state powers, except where the High Court certified the appeal. It did so only once: in the case of Colonial Sugar Refining Co v Attorney-General (Commonwealth) (1912). After that case, in which the Privy Council refused to answer the constitutional questions put to it, the High Court never certified another inter se appeal. Indeed, in the case of Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd (No 2)

Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd (No 2)

Kirmani v Captain Cook Cruises Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 27; 159 CLR 461, was a decision handed down in the High Court of Australia on 17 April 1985 concerning section 74 of the Constitution of Australia...

(1985), the court said that it would never again grant a certificate of appeal.

In general matters however, section 74 did not prevent the Privy Council from granting leave to appeal against the High Court's wishes, and the council did so often. In some cases, the council acknowledged that the Australian common law had developed differently from English law, and thus did not apply its own principles (for example, in Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v Uren (1967), or in Viro v The Queen (1978)), by using a legal fiction

Legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts which is then used in order to apply a legal rule which was not necessarily designed to be used in that way...

which stated that different common law can apply to different circumstances. However, in other cases, the Privy Council enforced English decisions, overruling decisions by the High Court. In Parker v The Queen (1963), Chief Justice Sir Owen Dixon

Owen Dixon

Sir Owen Dixon, OM, GCMG, KC Australian judge and diplomat, was the sixth Chief Justice of Australia. A justice of the High Court for thirty-five years, Dixon was one of the leading jurists in the English-speaking world and is widely regarded as Australia's greatest ever jurist.-Education:Dixon...

led a unanimous judgment which rejected a precedent of the House of Lords

Judicial functions of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, in addition to having a legislative function, historically also had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers, for impeachment cases, and as a court of last resort within the United Kingdom. In the latter case the House's...

in DPP v Smith, saying that "I shall not depart from the law on this matter as we have long since laid it down in this Court and I think that Smith's case should not be used in Australia as authority at all"; the following year the Privy Council upheld an appeal, applying the House of Lords precedent.

Section 74 did provide that the parliament could make laws to prevent appeals to the council, and it did so, beginning in 1968, with the Privy Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968, which closed off all appeals to the Privy Council in matters involving federal legislation. In 1975, the Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 was passed, which had the effect of closing all routes of appeal from the High Court. Appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council are now only theoretically possible in inter se

Inter se

Inter se is a Legal Latin phrase meaning "between or amongst themselves". For example;In Australian constitutional law, it refers to matters concerning a dispute between the Commonwealth and one or more of the States concerning the extents of their respective powers....

matters if the High Court grants a certificate of appeal under section 74 of the Constitution. As noted above, the High Court indicated in 1985 it would not grant such a certificate in the future, and it is practically certain that all future High Courts will maintain this policy. In 1986, with the passing of the Australia Acts

Australia Act 1986

The Australia Act 1986 is the name given to a pair of separate but related pieces of legislation: one an Act of the Commonwealth Parliament of Australia, the other an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

by both the UK Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

and the Parliament of Australia

Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

(with the ratification of the States

States and territories of Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia is a union of six states and various territories. The Australian mainland is made up of five states and three territories, with the sixth state of Tasmania being made up of islands. In addition there are six island territories, known as external territories, and a...

), appeals to the Privy Council from state Supreme Courts were closed off, leaving the High Court as the only avenue of appeal.

Appellate jurisdiction for Nauru

As per an agreement between NauruNauru

Nauru , officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country in Micronesia in the South Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, to the east. Nauru is the world's smallest republic, covering just...

and Australia in 1976, in application of article 57 of the Constitution of Nauru

Constitution of Nauru

The constitution of the Republic of Nauru was adopted following national independence on 31 January 1968.In 2007 there were political debates in progress with a view to amend aspects of the Constitution, owing to the challenge of widely acknowledged political instability...

, the High Court of Australia is the ultimate court of appeal for the sovereign Republic of Nauru, formerly an Australian colony. Thus the High Court may hear appeals from the Supreme Court of Nauru

Supreme Court of Nauru

The Supreme Court of Nauru is the highest judicial court of the Republic of Nauru.-Constitutional establishment:It is established by part V of the Constitution, adopted upon Nauru's independence from Australia in 1968. Art. 48 of the Constitution establishes the Supreme Court as "a superior court...

in both criminal and civil cases, with certain exceptions; in particular, no case pertaining to the Constitution of Nauru may be decided by the Australian court.

History

The genesis of the court can be traced back to the mid 19th century. Before the establishment of the High Court, appeals from the state Supreme Courts could be made only to the Judicial Committee of the Privy CouncilJudicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is one of the highest courts in the United Kingdom. Established by the Judicial Committee Act 1833 to hear appeals formerly heard by the King in Council The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is one of the highest courts in the United...

, which involved the great expense of physically travelling to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. As such, some politicians in the colonies wanted to have a new court which could travel between the colonies hearing appeals.

Following Earl Grey's 1846 proposal for federation of the Australian colonies, an 1849 report from the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, usually known simply as the Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the Sovereign in the United Kingdom...

suggested that a national court be created. In 1856, the then Governor of South Australia, Richard Graves MacDonnell

Richard Graves MacDonnell

Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell KCMG CB was an Anglo-Irish lawyer, judge and colonial governor...

, suggested to the Government of South Australia

Government of South Australia

The form of the Government of South Australia is prescribed in its constitution, which dates from 1856, although it has been amended many times since then...

that they and the other colonies should consider establishing a court of appeal which would hear appeals from the Supreme Courts in each colony, and in 1860 the Parliament of South Australia

Parliament of South Australia

The Parliament of South Australia is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of South Australia. It consists of the Legislative Council and the House of Assembly. It follows a Westminster system of parliamentary government....

passed legislation encouraging MacDonnell to put forward the idea to his colleagues in the other colonies. However, only the Government of Victoria

Government of Victoria

The Government of Victoria, under the Constitution of Australia, ceded certain legislative and judicial powers to the Commonwealth, but retained complete independence in all other areas...

seriously considered this proposal.

At an inter-colonial conference in 1870 in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

, Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

, the idea of an inter-colonial court was again raised, and subsequently a Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

was established in Victoria, to investigate options not only for establishing a court of appeal, but for unifying extradition

Extradition

Extradition is the official process whereby one nation or state surrenders a suspected or convicted criminal to another nation or state. Between nation states, extradition is regulated by treaties...

laws between the colonies and other similar matters. A draft bill establishing a court was put forward by the Commission, but it completely excluded appeals to the Privy Council, which reacted critically and prevented any serious attempts to implement the bill in London (before federation

Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia formed one nation...

, any laws affecting all the colonies would have to be passed by the British Imperial Parliament in London).

In 1880, another inter-colonial conference was convened, which proposed the establishment of an Australasian Court of Appeal. This conference was more firmly focused on having an Australian court. Another draft bill was produced, providing that judges from the colonial Supreme Courts would serve one-year terms on the new court, with one judge from each colony at a given time. New Zealand, which was at the time also considering joining the Australian colonies in federation, was also to be a participant in the new court. However, the proposal retained appeals from colonial Supreme Courts to the Privy Council, which some of the colonies disputed, and the bill was eventually abandoned.

Constitutional conventions

Constitutional Convention (Australia)

In Australian history, the term Constitutional Convention refers to four distinct gatherings.-1891 convention:The 1891 Constitutional Convention was held in Sydney in March 1891 to consider a draft Constitution for the proposed federation of the British colonies in Australia and New Zealand. There...

of the 1890s, which met to draft an Australian Constitution

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

, also raised the idea of a federal Supreme Court. Initial proposals at a conference in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

in February 1890 led to a convention in Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

in March and April 1891, which produced a draft constitution. The draft included the creation of a Supreme Court of Australia, which would not only interpret the Constitution, like the United States Supreme Court, but also would be a court of appeal from the state Supreme Courts. The draft effectively removed appeals to the Privy Council, allowing them only if the British monarch gave leave to appeal and not allowing appeals at all in constitutional matters.

This draft was largely the work of Sir Samuel Griffith

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith GCMG QC, was an Australian politician, Premier of Queensland, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and a principal author of the Constitution of Australia.-Early life:...

, then the Premier of Queensland, later Chief Justice of Queensland and the first Chief Justice of Australia

Chief Justice of Australia

The Chief Justice of Australia is the informal title for the presiding justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia...

. Other significant contributors to the judicial clauses in the draft included Attorney-General of Tasmania Andrew Inglis Clark

Andrew Inglis Clark

Andrew Inglis Clark was an Australian barrister, politician, electoral reformer and jurist. He initially qualified engineer, however he re-trained as a barrister in order to effectively fight for social causes which deeply concerned him...

, who had prepared his own constitution prior to the convention. Inglis Clark's most significant contribution was to give the court its own constitutional authority, ensuring the separation of powers

Separation of powers

The separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle, is a model for the governance of a state. The model was first developed in ancient Greece and came into widespread use by the Roman Republic as part of the unmodified Constitution of the Roman Republic...

; the original formulation from Griffith, Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

and Charles Kingston

Charles Kingston

Charles Cameron Kingston, Australian politician, was an early liberal Premier of South Australia serving from 1893 to 1899 with the support of Labor led by John McPherson from 1893 and Lee Batchelor from 1897 in the House of Assembly, winning the 1893, 1896, and 1899 state elections against the...

provided only that the parliament could establish a court.

Adelaide

Adelaide is the capital city of South Australia and the fifth-largest city in Australia. Adelaide has an estimated population of more than 1.2 million...