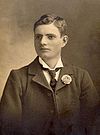

John Curtin

Encyclopedia

John Joseph Curtin Australian politician, served as the 14th Prime Minister of Australia

. Labor under Curtin formed a minority government

in 1941 after the crossbench consisting of two independent MPs crossed the floor

in the House of Representatives

, bringing down the Coalition

minority government of Robert Menzies

which resulted from the 1940 election

– aside from the formulative early parliaments, the only similar hung parliament

has resulted from the 2010 election. Curtin led federal Labor to its greatest win with two thirds of seats in the lower house and over 58 percent of the two-party preferred

vote at the 1943 election

. He died in 1945 and was succeeded by Ben Chifley

.

Curtin led Australia when the Australian mainland came under direct military threat during the Japanese advance in World War II

. He is widely regarded as one of the country's greatest Prime Ministers. General Douglas MacArthur

said that Curtin was "one of the greatest of the wartime statesmen". His Prime Ministerial predecessor and 1943 election Coalition leader, Arthur Fadden

of the Country Party

wrote: "I do not care who knows it but in my opinion there was no greater figure in Australian public life in my lifetime than Curtin."

Curtin was born in Creswick

Curtin was born in Creswick

in central Victoria. His name is sometimes shown as "John Joseph Ambrose Curtin". He chose the name "Ambrose" as a Catholic confirmation name at around age 14; this was never part of his legal name. He left the Catholic faith as a young man, and also dropped the "Ambrose" from his name.

His father was a police officer of Irish descent; Curtin attended school until the age of 14 when he started working for a newspaper in Creswick. He soon became active in both the Australian Labor Party

and the Victorian Socialist Party

, a Marxist group. He wrote for radical and socialist newspapers as "Jack Curtin".

It is believed that Curtin's first bid for a public office was when he stood for the position of secretary of the Brunswick

Australian rules football

club, and was defeated. He had earlier played for Brunswick between 1903 and 1907.

From 1911 until 1915 Curtin was employed as secretary of the Timberworkers' Union, and during World War I he was a militant anti-conscriptionist. He was the Labor candidate for Balaclava

in 1914. He was briefly imprisoned for refusing to attend a compulsory medical examination, even though he knew he would fail the exam due to his very poor eyesight. The strain of this period led him to drink heavily, a vice which blighted his career for many years. In 1917 he married Elsie Needham, the sister of Labor Senator Ted Needham

.

Curtin moved to Cottesloe near Perth in 1917 to become an editor for the Westralian Worker, the official trade union newspaper. He enjoyed the less pressured life of Western Australia

and his political views gradually moderated. He joined the Australian Journalists' Association in 1917 and was elected Western Australian President in 1920. He wore his AJA badge (WA membership #56) every day he was Prime Minister.

In addition to his stance on labour rights, Curtin was also a strong advocate for the rights of women and children. In 1927, the Federal Government convened a Royal Commission on Child Endowment Curtin was appointed as member of that commission.

Curtin stood as the Labor candidate for the federal seat of Fremantle

Curtin stood as the Labor candidate for the federal seat of Fremantle

, near Perth, in 1925

, losing badly to the incumbent, independent William Watson

. Watson retired in 1928

, and Curtin ran again, winning on the second count. Reelected in Labor's sweeping victory of 1929 election

, he expected to be named to James Scullin

's cabinet, but disapproval of his drinking kept him on the back bench. Watson roundly defeated him in 1931

as part of Labor's collapse to 14 seats nationwide. After the loss Curtin became the advocate for the Western Australian Government

with the Commonwealth Grants Commission

. He sought his old seat in 1934

after Watson retired for the second time, and won.

When Scullin resigned as Labor leader in 1935, Curtin was unexpectedly elected (by just one vote) to succeed him. The left wing and trade union group in the Caucus backed him because his better known rival, Frank Forde

, had supported the economic policies of the Scullin administration. This group also made him promise to give up drinking, which he did. He made little progress against Joseph Lyons

' government (which was returned to office at the 1937 election

by a comfortable margin); but after Lyons' death in 1939, Labor's position improved. Curtin led Labor to a five-seat swing in 1940 election

, coming within five seats of victory. In that election, Curtin's own seat of Fremantle was in doubt. United Australia Party

challenger Frederick Lee appeared to have won the seat on the second count after most of independent Guildford Clarke's preferences flowed to him, and it was not until final counting of preferential votes that Curtin knew he had won the seat.

In September 1939 the world plunged into war when Germany invaded Poland. Prime Minister Robert Menzies

In September 1939 the world plunged into war when Germany invaded Poland. Prime Minister Robert Menzies

proclaimed war on Germany as well and supported the UK war effort. In 1941 Menzies travelled to the UK to discuss Australia's role in the war strategy, and to express concern at the reliability of Singapore's defences. While he was in the UK, Menzies lost the support of his own party and was forced to resign. The UAP, senior partner in the non-Labor Coalition

, was so bereft of leadership that Arthur Fadden

, leader of the Country Party

, became Prime Minister.

Curtin had refused Menzies' offer to form a wartime "national government," partly because he feared it would split the Labor Party, though he did agree to join the Advisory War Council

. In October 1941, Arthur Coles

and Alexander Wilson

, the two independent MPs who had been keeping the Coalition (led first by Menzies, then by Fadden) in power since 1940, joined Labor in defeating Fadden's budget and brought the government down. Governor-General

Lord Gowrie

, reluctant to call an election given the international situation, summoned Coles and Wilson and made them promise that if he named Curtin Prime Minister, they would support him and end the instability in government. The independents agreed, and Curtin was sworn in on 7 October, aged 56.

On 7 December 1941, the Pacific War

On 7 December 1941, the Pacific War

broke out when Japan bombed Pearl Harbour

. Curtin addressed the nation on the radio: "Men and women of Australia. We are at war with Japan. This is the gravest hour of our history. We Australians have imperishable traditions. We shall maintain them. We shall vindicate them. We shall hold this country and keep it as a citadel for the British-speaking race and as a place where civilisation will persist." On 10 December HMS Prince of Wales (53) and HMS Repulse (1916)

were both sunk by Japanese bombers off the Malayan coast. These had been the last major battleships standing between Japan and the rest of Asia, Australia and the Pacific, except for a few survivors of the Pearl Harbor

attack. Curtin cabled Roosevelt and Churchill on 23 December: "The fall of Singapore would mean the isolation of the Philippines, the fall of the Netherlands East Indies and attempts to smother all other bases.It is in your power to meet the situation...we would gladly accept United States commander in Pacific area. Please consider this as a matter of urgency."

Curtin took several crucial decisions. On 26 December, the Melbourne Herald published a New Year

's message from Curtin, who wrote:

This historic speech is one of the most important in Australia's short history. It marks the turning point in Australia's relationship with its founding country, the United Kingdom. Many felt that Prime Minister Curtin was abandoning the ties with Great Britain without any solid partnership with the United States. This speech also received criticism at high levels of government in Australia, the UK and the US; it angered Winston Churchill

, and President Roosevelt

said it "smacked of panic". The article nevertheless achieved the effect of drawing attention to the possibility that Australia would be invaded by Japan. Before this speech the Australian response to the war effort was troubled by attitudes swinging from "she'll be right" to gossip driven panic.

Curtin formed a close working relationship with the Allied Supreme Commander in the South West Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur

. Curtin realised that Australia would be ignored unless it had a strong voice in Washington, and he wanted that voice to be MacArthur's. He gave control of Australian forces to MacArthur, directing Australian commanders to treat MacArthur's orders as coming from the Australian government.

The Australian government had agreed that the Australian Army's I Corps – centred on the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions – would be transferred from North Africa

to the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

, in the Netherlands East Indies. Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. It was Australia's worst military disaster since Gallipolli. The 8th Division was taken into captivity, a total of about 15,384 men, although Major-General Bennett managed to escape. In February, following the fall of Singapore

and the loss of the 8th Division, Churchill attempted to divert I Corps to reinforce British troops in Burma, without Australian approval. Curtin insisted that it return to Australia, although he agreed that the main body of the 6th Division could garrison Ceylon.

The Japanese threat was underlined on 19 February, when Japan bombed Darwin, the first of many air raids on northern Australia

.

By the end of 1942, the results of the battles of the Coral Sea

, Milne Bay

and on the Kokoda Track

had averted the perceived threat of invasion.

Curtin also expanded the terms of the Defence Act, so that conscripted Militia

soldiers could be deployed outside Australia to "such other territories in the South-west Pacific Area as the Governor-General proclaims as being territories associated with the defence of Australia". This met opposition from most of Curtin's old friends on the left, and from many of his colleagues, led by Arthur Calwell

. This was despite Curtin furiously opposing conscription during World War I

, and again in 1939 when it was introduced by the Menzies

government. The stress of this bitter battle inside his own party took a great toll on Curtin's health, never robust even at the best of times. He suffered all his life from stress-related illnesses, and he also smoked heavily. It became common practice during these years for Curtin and many others in government to work sixteen hours a day.

, Curtin led Labor to its greatest election victory, winning two-thirds of the seats in the House of Representatives

on a two-party preferred vote of 58.2 percent. Labor also won the primary vote in all states and thus all 19 seats in the Senate

, to hold a total of 22 of 36 seats.

Bouyed by the success of the 1943 election, Curtin tried to centralise power by holding a referendum in which would give the government control of the economy and resources for five years after the war was won. The 1944 Australian Referendum

was held on 19 August 1944. It contained one referendum question. Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944'?

Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944 was known as the 14 powers, or 14 points referendum. It sought to give the government power over a period of five years, to legislate on a wide variety of matters. The referendum was defeated.

On 5 July 1945, at the age of 60, Curtin died, the only Prime Minister to die at The Lodge. He was the second Australian Prime Minister to die in office within six years. His body was returned to Perth

on a RAAF Dakota escorted by a flight of nine fighter aircraft. He was buried at Karrakatta Cemetery

in Perth; the service was attended by over 30,000 at the cemetery with many more lining the streets. MacArthur said of Curtin that "the preservation of Australia from invasion will be his immemorial monument".

He was briefly succeeded as Prime Minister by Frank Forde

, then a week later, after a party ballot, by Ben Chifley

.

Curtin is credited with leading the Australian Labor Party

Curtin is credited with leading the Australian Labor Party

to its best federal election success in history, with a record 55.1 percent of the primary half-senate vote, winning all seats, and a two party preferred lower house estimate of 58.2 percent at the 1943 election

, winning two-thirds of seats.

One important legacy of Curtin's was the significant expansion of social services under his leadership. In 1942, uniform taxation was imposed on the various states, which enabled the Curtin Government to set up a far-reaching, federally administered range of social services. These included a widows’ pension (1942), maternity benefits for Aborigines (1942), funeral benefits (1943), a wife’s allowance (1943), additional allowances for the children of pensioners (1943), unemployment, sickness and Special Benefits (1945), and pharmaceutical benefits (1945). Substantial improvements to pensions were made, with invalidity and old-age pensions increased, the qualifying period of residence for age pensions halved, and the means test liberalised. Other social security benefits were significantly increased, while child endowment was liberalised, a scheme of vocational training for invalid pensioners was set up, and pensions extended to cover aborigines. The expansion of social security under John Curtin was of such significance that, as summed up one historian,

“Australia entered World War II with only a fragmentary welfare provision: by the end of the war it had constructed a ‘welfare state’”.

His early death and the sentiments it aroused have given Curtin a unique place in Australian political history. Successive Labor leaders, particularly Bob Hawke

and Kim Beazley

, have sought to build on the Curtin tradition of "patriotic Laborism". Even some political conservatives pay at least formal homage to the Curtin legend. Immediately after his death the parliament agreed to pay John Curtin's wife Elsie A£1,000 per annum until legislation was passed and enacted to pay a pension to past Prime Minister or their spouse after their death.

Curtin is commemorated by Curtin University in Perth, John Curtin College of the Arts

in Fremantle

, the John Curtin School of Medical Research

in Canberra, the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, Curtin Avenue in Perth's western suburbs, and the John Curtin Hotel on Lygon St, Carlton, Melbourne. On 14 August 2005, the 60th anniversary of V-P Day, a bronze statue of Curtin in front of Fremantle Town Hall

was unveiled by Premier of Western Australia

Geoff Gallop

.

Curtin House

in Swanston St, Melbourne is named after him.

In 1975 Curtin was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

.

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

. Labor under Curtin formed a minority government

Minority government

A minority government or a minority cabinet is a cabinet of a parliamentary system formed when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in the parliament but is sworn into government to break a Hung Parliament election result. It is also known as a...

in 1941 after the crossbench consisting of two independent MPs crossed the floor

Crossing the floor

In politics, crossing the floor has two meanings referring to a change of allegiance in a Westminster system parliament.The term originates from the British House of Commons, which is configured with the Government and Opposition facing each other on rows of benches...

in the House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

, bringing down the Coalition

Coalition (Australia)

The Coalition in Australian politics refers to a group of centre-right parties that has existed in the form of a coalition agreement since 1922...

minority government of Robert Menzies

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, , Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia....

which resulted from the 1940 election

Australian federal election, 1940

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 September 1940. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

– aside from the formulative early parliaments, the only similar hung parliament

Hung parliament

In a two-party parliamentary system of government, a hung parliament occurs when neither major political party has an absolute majority of seats in the parliament . It is also less commonly known as a balanced parliament or a legislature under no overall control...

has resulted from the 2010 election. Curtin led federal Labor to its greatest win with two thirds of seats in the lower house and over 58 percent of the two-party preferred

Two-party-preferred vote

In politics, the two-party-preferred vote , or two-candidate-preferred vote , in an election or opinion poll uses preferential voting to express the electoral result after the distribution of preferences...

vote at the 1943 election

Australian federal election, 1943

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 August 1943. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Australian Labor Party led by Prime Minister of Australia John Curtin easily defeated the opposition Country Party led...

. He died in 1945 and was succeeded by Ben Chifley

Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley , Australian politician, was the 16th Prime Minister of Australia. He took over the Australian Labor Party leadership and Prime Ministership after the death of John Curtin in 1945, and went on to retain government at the 1946 election, before being defeated at the 1949...

.

Curtin led Australia when the Australian mainland came under direct military threat during the Japanese advance in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. He is widely regarded as one of the country's greatest Prime Ministers. General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

said that Curtin was "one of the greatest of the wartime statesmen". His Prime Ministerial predecessor and 1943 election Coalition leader, Arthur Fadden

Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, GCMG was an Australian politician and, briefly, the 13th Prime Minister of Australia.-Introduction:...

of the Country Party

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Traditionally representing graziers, farmers and rural voters generally, it began as the The Country Party, but adopted the name The National Country Party in 1975, changed to The National Party of Australia in 1982. The party is...

wrote: "I do not care who knows it but in my opinion there was no greater figure in Australian public life in my lifetime than Curtin."

Early life

Creswick, Victoria

Creswick is a town in west-central Victoria, Australia. It is located 18 kilometres north of Ballarat and 129 km northwest of Melbourne, in Shire of Hepburn. It is 430 metres above sea level. At the 2006 census, Creswick had a population of 2,485...

in central Victoria. His name is sometimes shown as "John Joseph Ambrose Curtin". He chose the name "Ambrose" as a Catholic confirmation name at around age 14; this was never part of his legal name. He left the Catholic faith as a young man, and also dropped the "Ambrose" from his name.

His father was a police officer of Irish descent; Curtin attended school until the age of 14 when he started working for a newspaper in Creswick. He soon became active in both the Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

and the Victorian Socialist Party

Victorian Socialist Party

The Victorian Socialist Party was a socialist political party in Victoria, Australia in the early 20th century. The VSP was founded in 1906 in Melbourne, bringing together a number of older socialist groupings. A leading influence in the VSP's formation was the British trade unionist Tom Mann, who...

, a Marxist group. He wrote for radical and socialist newspapers as "Jack Curtin".

It is believed that Curtin's first bid for a public office was when he stood for the position of secretary of the Brunswick

Brunswick Football Club

Brunswick Football Club was an Australian rules football club which played in the VFA from 1897 until 1990. They were originally nicknamed the Pottery Workers before being renamed the Magpies and were based in Brunswick, Victoria. The club wore black and white guernseys...

Australian rules football

Australian rules football

Australian rules football, officially known as Australian football, also called football, Aussie rules or footy is a sport played between two teams of 22 players on either...

club, and was defeated. He had earlier played for Brunswick between 1903 and 1907.

From 1911 until 1915 Curtin was employed as secretary of the Timberworkers' Union, and during World War I he was a militant anti-conscriptionist. He was the Labor candidate for Balaclava

Division of Balaclava

The Division of Balaclava was an Australian Electoral Division in Victoria. The division was created in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It was named for the suburb of Balaclava, which in turn was named for a battlefield of the Crimean War...

in 1914. He was briefly imprisoned for refusing to attend a compulsory medical examination, even though he knew he would fail the exam due to his very poor eyesight. The strain of this period led him to drink heavily, a vice which blighted his career for many years. In 1917 he married Elsie Needham, the sister of Labor Senator Ted Needham

Ted Needham

Edward "Ted" Needham was an English-born Australian politician. Born in Lancashire, he was educated at Catholic schools before becoming a coal miner and shipyard worker. He migrated to Australia in 1900, becoming a boilermaker in Fremantle, Western Australia...

.

Curtin moved to Cottesloe near Perth in 1917 to become an editor for the Westralian Worker, the official trade union newspaper. He enjoyed the less pressured life of Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

and his political views gradually moderated. He joined the Australian Journalists' Association in 1917 and was elected Western Australian President in 1920. He wore his AJA badge (WA membership #56) every day he was Prime Minister.

In addition to his stance on labour rights, Curtin was also a strong advocate for the rights of women and children. In 1927, the Federal Government convened a Royal Commission on Child Endowment Curtin was appointed as member of that commission.

Early political career

Division of Fremantle

The Division of Fremantle is an Australian Electoral Division in Western Australia.The division was created at Federation in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election...

, near Perth, in 1925

Australian federal election, 1925

Federal elections were held in Australia on 14 November 1925. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 22 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, losing badly to the incumbent, independent William Watson

William Watson (Australian politician)

William Watson was an Australian politician. Born in Campbells Creek, Victoria, he was educated at public schools before becoming a miner, bricklayer and farmer. In 1893, he left Victoria for Western Australia, where he became a bacon manufacturer in Fremantle, and became known as a local benefactor...

. Watson retired in 1928

Australian federal election, 1928

Federal elections were held in Australia on 17 November 1928. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, and Curtin ran again, winning on the second count. Reelected in Labor's sweeping victory of 1929 election

Australian federal election, 1929

Federal elections were held in Australia on 12 October 1929. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, with no Senate seats up for election, as a result of Billy Hughes and other rebel backbenchers crossing the floor over industrial relations legislation, depriving the...

, he expected to be named to James Scullin

James Scullin

James Henry Scullin , Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression and subsequent Great Depression in Australia.-Early life:Scullin was...

's cabinet, but disapproval of his drinking kept him on the back bench. Watson roundly defeated him in 1931

Australian federal election, 1931

Federal elections were held in Australia on 19 December 1931. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

as part of Labor's collapse to 14 seats nationwide. After the loss Curtin became the advocate for the Western Australian Government

Government of Western Australia

The formation of the Government of Western Australia is prescribed in its Constitution, which dates from 1890, although it has been amended many times since then...

with the Commonwealth Grants Commission

Commonwealth Grants Commission

The Commonwealth Grants Commission is an Australian government body that advises on Australian Government financial assistance to the states and territories of Australia with the aim of achieving Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation....

. He sought his old seat in 1934

Australian federal election, 1934

Federal elections were held in Australia on 15 September 1934. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent United Australia Party led by Prime Minister of Australia Joseph Lyons with coalition partner the Country Party led...

after Watson retired for the second time, and won.

When Scullin resigned as Labor leader in 1935, Curtin was unexpectedly elected (by just one vote) to succeed him. The left wing and trade union group in the Caucus backed him because his better known rival, Frank Forde

Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde PC was an Australian politician and the 15th Prime Minister of Australia. He was the shortest serving Prime Minister in Australia's history, being in office for only eight days.-Early life:...

, had supported the economic policies of the Scullin administration. This group also made him promise to give up drinking, which he did. He made little progress against Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

' government (which was returned to office at the 1937 election

Australian federal election, 1937

Federal elections were held in Australia on 23 October 1937. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

by a comfortable margin); but after Lyons' death in 1939, Labor's position improved. Curtin led Labor to a five-seat swing in 1940 election

Australian federal election, 1940

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 September 1940. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, coming within five seats of victory. In that election, Curtin's own seat of Fremantle was in doubt. United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

challenger Frederick Lee appeared to have won the seat on the second count after most of independent Guildford Clarke's preferences flowed to him, and it was not until final counting of preferential votes that Curtin knew he had won the seat.

Prime minister

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, , Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia....

proclaimed war on Germany as well and supported the UK war effort. In 1941 Menzies travelled to the UK to discuss Australia's role in the war strategy, and to express concern at the reliability of Singapore's defences. While he was in the UK, Menzies lost the support of his own party and was forced to resign. The UAP, senior partner in the non-Labor Coalition

Coalition (Australia)

The Coalition in Australian politics refers to a group of centre-right parties that has existed in the form of a coalition agreement since 1922...

, was so bereft of leadership that Arthur Fadden

Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, GCMG was an Australian politician and, briefly, the 13th Prime Minister of Australia.-Introduction:...

, leader of the Country Party

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Traditionally representing graziers, farmers and rural voters generally, it began as the The Country Party, but adopted the name The National Country Party in 1975, changed to The National Party of Australia in 1982. The party is...

, became Prime Minister.

Curtin had refused Menzies' offer to form a wartime "national government," partly because he feared it would split the Labor Party, though he did agree to join the Advisory War Council

Advisory War Council (Australia)

The Advisory War Council was an Australian Government body during World War II. The AWC was established on 28 October 1940 to draw all the major political parties in the Parliament of Australia into the process of making decisions on Australia's war effort and was disbanded on 30 August...

. In October 1941, Arthur Coles

Arthur Coles

Sir Arthur William Coles was a prominent Australian businessman and philanthropist.With his brothers Coles founded the Coles Variety Stores in the 1920s, which were to become one of the two largest supermarket chains in Australia now known as Coles Group...

and Alexander Wilson

Alexander Wilson (Australian politician)

Alexander Wilson was an Australian wheat farmer and politician.-Biography:Born in County Down, Ireland, he was educated at Belfast and migrated to Australia in 1908, becoming a farmer at Ultima, Victoria. He was prominent as a leader of Victorian wheatgrowers...

, the two independent MPs who had been keeping the Coalition (led first by Menzies, then by Fadden) in power since 1940, joined Labor in defeating Fadden's budget and brought the government down. Governor-General

Governor-General of Australia

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

Lord Gowrie

Alexander Hore-Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie

Brigadier General Alexander Gore Arkwright Hore-Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie VC, GCMG, CB, DSO & Bar, PC was a British soldier and colonial governor and the tenth Governor-General of Australia. Serving for 9 years and 7 days, he is the longest serving Governor-General in Australia's history...

, reluctant to call an election given the international situation, summoned Coles and Wilson and made them promise that if he named Curtin Prime Minister, they would support him and end the instability in government. The independents agreed, and Curtin was sworn in on 7 October, aged 56.

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

broke out when Japan bombed Pearl Harbour

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

. Curtin addressed the nation on the radio: "Men and women of Australia. We are at war with Japan. This is the gravest hour of our history. We Australians have imperishable traditions. We shall maintain them. We shall vindicate them. We shall hold this country and keep it as a citadel for the British-speaking race and as a place where civilisation will persist." On 10 December HMS Prince of Wales (53) and HMS Repulse (1916)

HMS Repulse (1916)

HMS Repulse was a Renown-class battlecruiser of the Royal Navy built during the First World War. She was originally laid down as an improved version of the s. Her construction was suspended on the outbreak of war on the grounds she would not be ready in a timely manner...

were both sunk by Japanese bombers off the Malayan coast. These had been the last major battleships standing between Japan and the rest of Asia, Australia and the Pacific, except for a few survivors of the Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor, known to Hawaiians as Puuloa, is a lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. Much of the harbor and surrounding lands is a United States Navy deep-water naval base. It is also the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet...

attack. Curtin cabled Roosevelt and Churchill on 23 December: "The fall of Singapore would mean the isolation of the Philippines, the fall of the Netherlands East Indies and attempts to smother all other bases.It is in your power to meet the situation...we would gladly accept United States commander in Pacific area. Please consider this as a matter of urgency."

Curtin took several crucial decisions. On 26 December, the Melbourne Herald published a New Year

New Year

The New Year is the day that marks the time of the beginning of a new calendar year, and is the day on which the year count of the specific calendar used is incremented. For many cultures, the event is celebrated in some manner....

's message from Curtin, who wrote:

This historic speech is one of the most important in Australia's short history. It marks the turning point in Australia's relationship with its founding country, the United Kingdom. Many felt that Prime Minister Curtin was abandoning the ties with Great Britain without any solid partnership with the United States. This speech also received criticism at high levels of government in Australia, the UK and the US; it angered Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, and President Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

said it "smacked of panic". The article nevertheless achieved the effect of drawing attention to the possibility that Australia would be invaded by Japan. Before this speech the Australian response to the war effort was troubled by attitudes swinging from "she'll be right" to gossip driven panic.

Curtin formed a close working relationship with the Allied Supreme Commander in the South West Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

. Curtin realised that Australia would be ignored unless it had a strong voice in Washington, and he wanted that voice to be MacArthur's. He gave control of Australian forces to MacArthur, directing Australian commanders to treat MacArthur's orders as coming from the Australian government.

The Australian government had agreed that the Australian Army's I Corps – centred on the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions – would be transferred from North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

to the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian Command, or ABDACOM, was a short-lived, supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia, in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II...

, in the Netherlands East Indies. Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. It was Australia's worst military disaster since Gallipolli. The 8th Division was taken into captivity, a total of about 15,384 men, although Major-General Bennett managed to escape. In February, following the fall of Singapore

Battle of Singapore

The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of the Second World War when the Empire of Japan invaded the Allied stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in Southeast Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East"...

and the loss of the 8th Division, Churchill attempted to divert I Corps to reinforce British troops in Burma, without Australian approval. Curtin insisted that it return to Australia, although he agreed that the main body of the 6th Division could garrison Ceylon.

The Japanese threat was underlined on 19 February, when Japan bombed Darwin, the first of many air raids on northern Australia

Japanese air attacks on Australia, 1942-43

Between February 1942 and November 1943, during the Pacific War, the Australian mainland, domestic airspace, offshore islands and coastal shipping were attacked at least 97 times by aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army Air Force...

.

By the end of 1942, the results of the battles of the Coral Sea

Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, fought from 4–8 May 1942, was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II between the Imperial Japanese Navy and Allied naval and air forces from the United States and Australia. The battle was the first fleet action in which aircraft carriers engaged...

, Milne Bay

Battle of Milne Bay

The Battle of Milne Bay, also known as Operation RE by the Japanese, was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II. Japanese marines attacked the Australian base at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of New Guinea on 25 August 1942, and fighting continued until the Japanese retreated on 5...

and on the Kokoda Track

Kokoda Track campaign

The Kokoda Track campaign or Kokoda Trail campaign was part of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign consisted of a series of battles fought between July and November 1942 between Japanese and Allied—primarily Australian—forces in what was then the Australian territory of Papua...

had averted the perceived threat of invasion.

Curtin also expanded the terms of the Defence Act, so that conscripted Militia

Australian Army Reserve

The Australian Army Reserve is a collective name given to the reserve units of the Australian Army. Since the Federation of Australia in 1901, the reserve military force has been known by many names, including the Citizens Forces, the Citizen Military Forces, the Militia and, unofficially, the...

soldiers could be deployed outside Australia to "such other territories in the South-west Pacific Area as the Governor-General proclaims as being territories associated with the defence of Australia". This met opposition from most of Curtin's old friends on the left, and from many of his colleagues, led by Arthur Calwell

Arthur Calwell

Arthur Augustus Calwell Australian politician, was a member of the Australian House of Representatives for 32 years from 1940 to 1972, Immigration Minister in the government of Ben Chifley from 1945 to 1949 and Leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1960 to 1967.-Early life:Calwell was born in...

. This was despite Curtin furiously opposing conscription during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, and again in 1939 when it was introduced by the Menzies

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, , Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia....

government. The stress of this bitter battle inside his own party took a great toll on Curtin's health, never robust even at the best of times. He suffered all his life from stress-related illnesses, and he also smoked heavily. It became common practice during these years for Curtin and many others in government to work sixteen hours a day.

Election and referendum

At the 1943 electionAustralian federal election, 1943

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 August 1943. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Australian Labor Party led by Prime Minister of Australia John Curtin easily defeated the opposition Country Party led...

, Curtin led Labor to its greatest election victory, winning two-thirds of the seats in the House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

on a two-party preferred vote of 58.2 percent. Labor also won the primary vote in all states and thus all 19 seats in the Senate

Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. Senators are popularly elected under a system of proportional representation. Senators are elected for a term that is usually six years; after a double dissolution, however,...

, to hold a total of 22 of 36 seats.

Bouyed by the success of the 1943 election, Curtin tried to centralise power by holding a referendum in which would give the government control of the economy and resources for five years after the war was won. The 1944 Australian Referendum

Australian referendum, 1944

The 1944 Australian Referendum was held on 19 August 1944. It contained one referendum question.* Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights -Proposed Amendment:...

was held on 19 August 1944. It contained one referendum question. Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944'?

Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944 was known as the 14 powers, or 14 points referendum. It sought to give the government power over a period of five years, to legislate on a wide variety of matters. The referendum was defeated.

Failing health

In 1944, when he travelled to Washington and London for meetings with Roosevelt, Churchill and other Allied leaders, he already had heart disease, and in early 1945 his health deteriorated still more obviously.On 5 July 1945, at the age of 60, Curtin died, the only Prime Minister to die at The Lodge. He was the second Australian Prime Minister to die in office within six years. His body was returned to Perth

Perth, Western Australia

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia and the fourth most populous city in Australia. The Perth metropolitan area has an estimated population of almost 1,700,000....

on a RAAF Dakota escorted by a flight of nine fighter aircraft. He was buried at Karrakatta Cemetery

Karrakatta Cemetery

Karrakatta Cemetery is a metropolitan cemetery in the suburb of Karrakatta in Perth, Western Australia. Karrakatta Cemetery first opened for burials in 1899, with Robert Creighton. Currently managed by the Metropolitan Cemeteries Board, the cemetery attracts more than one million visitors each...

in Perth; the service was attended by over 30,000 at the cemetery with many more lining the streets. MacArthur said of Curtin that "the preservation of Australia from invasion will be his immemorial monument".

He was briefly succeeded as Prime Minister by Frank Forde

Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde PC was an Australian politician and the 15th Prime Minister of Australia. He was the shortest serving Prime Minister in Australia's history, being in office for only eight days.-Early life:...

, then a week later, after a party ballot, by Ben Chifley

Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley , Australian politician, was the 16th Prime Minister of Australia. He took over the Australian Labor Party leadership and Prime Ministership after the death of John Curtin in 1945, and went on to retain government at the 1946 election, before being defeated at the 1949...

.

Legacy

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

to its best federal election success in history, with a record 55.1 percent of the primary half-senate vote, winning all seats, and a two party preferred lower house estimate of 58.2 percent at the 1943 election

Australian federal election, 1943

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 August 1943. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Australian Labor Party led by Prime Minister of Australia John Curtin easily defeated the opposition Country Party led...

, winning two-thirds of seats.

One important legacy of Curtin's was the significant expansion of social services under his leadership. In 1942, uniform taxation was imposed on the various states, which enabled the Curtin Government to set up a far-reaching, federally administered range of social services. These included a widows’ pension (1942), maternity benefits for Aborigines (1942), funeral benefits (1943), a wife’s allowance (1943), additional allowances for the children of pensioners (1943), unemployment, sickness and Special Benefits (1945), and pharmaceutical benefits (1945). Substantial improvements to pensions were made, with invalidity and old-age pensions increased, the qualifying period of residence for age pensions halved, and the means test liberalised. Other social security benefits were significantly increased, while child endowment was liberalised, a scheme of vocational training for invalid pensioners was set up, and pensions extended to cover aborigines. The expansion of social security under John Curtin was of such significance that, as summed up one historian,

“Australia entered World War II with only a fragmentary welfare provision: by the end of the war it had constructed a ‘welfare state’”.

His early death and the sentiments it aroused have given Curtin a unique place in Australian political history. Successive Labor leaders, particularly Bob Hawke

Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee "Bob" Hawke AC GCL was the 23rd Prime Minister of Australia from March 1983 to December 1991 and therefore longest serving Australian Labor Party Prime Minister....

and Kim Beazley

Kim Beazley

In the October 1998 election, Labor polled a majority of the two-party vote and received the largest swing to a first-term opposition since 1934. However, due to the uneven nature of the swing, Labor came up eight seats short of making Beazley Prime Minister....

, have sought to build on the Curtin tradition of "patriotic Laborism". Even some political conservatives pay at least formal homage to the Curtin legend. Immediately after his death the parliament agreed to pay John Curtin's wife Elsie A£1,000 per annum until legislation was passed and enacted to pay a pension to past Prime Minister or their spouse after their death.

Curtin is commemorated by Curtin University in Perth, John Curtin College of the Arts

John Curtin College of the Arts

John Curtin College of the Arts is a high school with student intake from the greater Fremantle area, in Western Australia. The school currently has over 1100 students attending....

in Fremantle

Fremantle, Western Australia

Fremantle is a city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle was the first area settled by the Swan River colonists in 1829...

, the John Curtin School of Medical Research

John Curtin School of Medical Research

The John Curtin School of Medical Research is a major biomedical research centre in Australia, and part of the Australian National University, Canberra. The school was founded in 1948, as a result of the vision of Australian Nobel Laureate Sir Howard Florey and Prime Minister John Curtin.The Nobel...

in Canberra, the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, Curtin Avenue in Perth's western suburbs, and the John Curtin Hotel on Lygon St, Carlton, Melbourne. On 14 August 2005, the 60th anniversary of V-P Day, a bronze statue of Curtin in front of Fremantle Town Hall

Fremantle Town Hall

Fremantle Town Hall is a town hall located in the portside city of Fremantle, Western Australia and situated on the corner of High, William and Adelaide Streets. The opening coincided with the celebration of Victoria's Jubilee and occurred on 22 June 1887....

was unveiled by Premier of Western Australia

Premier of Western Australia

The Premier of Western Australia is the head of the executive government in the Australian State of Western Australia. The Premier has similar functions in Western Australia to those performed by the Prime Minister of Australia at the national level, subject to the different Constitutions...

Geoff Gallop

Geoff Gallop

Geoffrey Ian Gallop, AC is an Australian academic and former politician. He was the Premier of Western Australia from 2001 to 2006. He currently resides in Sydney.-Early life and education:...

.

Curtin House

Curtin House

Curtin House is a six storey Art Nouveau building on Swanston Street in the Melbourne CBD that hosts thai restaurant and bar Cookie, , a family owned and operated Kung Fu academy; , website developers , bookstore , rare record store and music venue - , which hosts cabaret, comedy, acoustic, blues,...

in Swanston St, Melbourne is named after him.

In 1975 Curtin was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

.

Popular culture

- In the 1984 mini series The Last BastionThe Last BastionThe Last Bastion is a television mini-series which aired in Australia in November 1984. It tells the story of Australia's involvement in World War II, and its often strained relations with its two main allies, Great Britain and the United States.-Cast:...

, Curtin was portrayed by Michael BlakemoreMichael BlakemoreMichael Howell Blakemore OBE is an Australian actor, writer and theatre director. In 2000 he became the only individual to win Tony Awards for best Director of a Play and Musical in the same year for Copenhagen and Kiss Me, Kate....

. - In the 1986 film Death of a SoldierDeath of a SoldierDeath of a Soldier is a 1986 Australian film based on the life of American serial killer Eddie Leonski. The film was shot using locations around Melbourne, Victoria.The film is directed by Philippe Mora and stars James Coburn, Bill Hunter and Reb Brown....

, he was portrayed by Terence DonovanTerence Donovan (actor)Terence Donovan , also known as Terry Donovan, is an English-born Australian actor and the father of fellow actor and entertainer Jason Donovan...

. - In the 2000 film Pozieres, he was portrayed by David Ross Paterson.

- In the 2007 Telemovie CurtinCurtin (2007 film)Curtin is a telemovie about the wartime Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin.-Plot:The film covers the period from just before Curtin became Prime Minister until the return of the 6th and 7th Divisions to Australia at the start of the Pacific war....

, he was portrayed by William McInnesWilliam McInnesWilliam McInnes is an Australian film and television actor and writer.-Television:After a recurring role on A Country Practice in 1990, McInnes appeared in series such as Bligh, Ocean Girl, and Snowy before making his name as Senior Constable Nick Schultz on Blue Heelers in 1994...

.

See also

- First Curtin MinistryFirst Curtin MinistryThe First Curtin Ministry was the thirtieth Australian Commonwealth ministry, and held office from 7 October 1941 to 21 September 1943.Australian Labor Party...

- Second Curtin MinistrySecond Curtin MinistryThe Second Curtin Ministry was the thirty-first Australian Commonwealth ministry, and held office from 21 September 1943 to 6 July 1945.Australian Labor Party*Rt Hon John Curtin, MP: Prime Minister, Minister for Defence...

- Military history of Australia during World War IIMilitary history of Australia during World War IIAustralia entered World War II shortly after the invasion of Poland, declaring war on Germany on 3 September 1939. By the end of the war, almost a million Australians had served in the armed forces, whose military units fought primarily in the European theatre, North African campaign, and...

- Residence of John Curtin

Further reading

- Butlin, S.J. and Schedvin, C.B (1997) War Economy 1942–1945, Australian War Memorial, Canberra. ISBN 0642994064

- Day, David (1999) Curtin: A Life, HarperCollins, Pymble, New South Wales. ISBN 0207196699

- Dowsing, Irene (1969) Curtin of Australia, Acacia Press, Melbourne. ISBN 9130001218.

- Hughes, Colin AColin HughesColin Anfield Hughes is an Australian academic specializing in electoral politics and government.He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Columbia University and his Ph.D from the London School of Economics. In 1966, along with John S...

(1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.15. ISBN 0 19 550471 2 - Ross, Lloyd (1977), John Curtin, MacMillan Company of Australia, Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 0 522 84734 X

- Wurth, Bob (2006) Saving Australia: Curtin’s secret peace with Japan, Lothian Press, South Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 0734409044

Primary sources

- Black, D. (1995) In His Own Words: John Curtin's Speeches and Writings, Paradigm Books, Curtin University, Perth.

External links

- David Day, Chapter 7. John Curtin: Taking his Childhood Seriously, Australian Political Lives: Chronicling political careers and administrative histories

- John Edwards, Curtin's Gift: Reinterpreting Australia's Greatest Prime Minister, Allen & Unwin, 2005

- John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library / Curtin University of Technology, Western Australia

- WW2DB: John Curtin

- John Curtin (1885–1945) – Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition

- John Curtinâs Australian Journalistsâ Association Badge – English and Media Literacy, Australian Biography at dl.filmaust.com.au – Prime Ministers' Natural Treasures

- Listen to John Curtin declaring that Australia is at war with Japan in 1941 on australianscreen online

- The recording 'Curtin Speech: Japan Enters Second World War, 1941' was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia Registry in 2010