Hildegard of Bingen

Encyclopedia

Blessed Hildegard of Bingen (1098 – 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard, and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic

, Benedictine

abbess

, visionary

, and polymath

. Elected a magistra by her fellow nuns in 1136, she founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg

in 1150 and Eibingen

in 1165. One of her works as a composer, the Ordo Virtutum

, is an early example of liturgical drama.

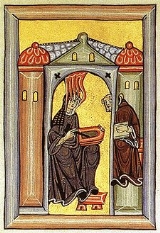

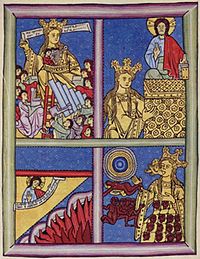

She wrote theological, botanical and medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs, poems, and arguably the oldest surviving morality play

, while supervising brilliant miniature Illuminations.

Hildegard of Bingen's date of birth is uncertain. It has been concluded that she may have been born in the year 1098. Hildegard was raised in a family of free nobles. She was her parents' tenth child, sickly from birth. In her Vita, Hildegard explains that from a very young age she had experienced visions

Hildegard of Bingen's date of birth is uncertain. It has been concluded that she may have been born in the year 1098. Hildegard was raised in a family of free nobles. She was her parents' tenth child, sickly from birth. In her Vita, Hildegard explains that from a very young age she had experienced visions

.

Perhaps due to Hildegard's visions, or as a method of political positioning, Hildegard's parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, offered her as a tithe

to the church. The date of Hildegard's enclosure in the church is contentious. Her Vita tells us she was enclosed with an older nun, Jutta, at the age of eight. However, Jutta's enclosure date is known to be in 1112, at which time Hildegard would have been fourteen. Some scholars speculate that Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta

, the daughter of Count Stephan II of Sponheim, at the age of eight, before the two women were enclosed together six years later. There is no written record of the twenty-four years of Hildegard's life that she was in the convent together with Jutta. It is possible that Hildegard could have been a chantress and a worker in the herbarium and infirmarium. In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed at Disibodenberg

in the Palatinate Forest in what is now Germany. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the enclosure. Hildegard also tells us that Jutta taught her to read and write, but that she was unlearned and therefore incapable of teaching Hildegard Biblical interpretation. Hildegard and Jutta most likely prayed, meditated, read scriptures such as the psalter, and did some sort of handwork during the hours of the Divine Office. This also might have been a time when Hildegard learned how to play the ten-stringed psaltery

. Volmar, a frequent visitor, may have taught Hildegard simple psalm notation. The time she studied music could also have been the beginning of the compositions she would later create.

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as "magistra" of her sister community by her fellow nuns. Abbot Kuno, the Abbot of Disibodenberg, also asked Hildegard to be Prioress. Hildegard, however, wanted more independence for herself and her nuns and asked Abbot Kuno to allow them to move to Rupertsberg

. This was to be a move towards poverty from a stone complex that was well established to a temporary dwelling place. (New York: Routledge, 2001), 6. When the abbot declined Hildegard's proposition, Hildegard went over his head and received the approval of Archbishop Henry I of Mainz. Abbot Kuno did not relent, however, until Hildegard was stricken by an illness that kept her paralyzed and unable to move from her bed, an event that she attributed to God's unhappiness at her not following his orders to move her nuns to Rupertsberg. It was only when the Abbot himself could not move Hildegard that he decided to grant the nuns their own monastery. Hildegard and about twenty nuns thus moved to the St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar served as provost, as well as Hildegard's confessor and scribe. In 1165 Hildegard founded a second convent for her nuns at Eibingen

.

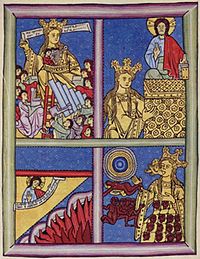

Hildegard says that she first saw "The Shade of the Living Light" at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions. She used the term 'visio' to this feature of her experience, and recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Hildegard was hesitant to share her visions, confiding only to Jutta

, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, secretary. Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions, and in 1141, at the age of 42, Hildegard received a vision she believed to be an instruction from God, to "write down that which you see and hear." Still hesitant to record her visions, Hildegard became physically ill. The illustrations recorded in the book of Scivias were visions that Hildegard experienced, causing her great

suffering and tribulations. In her first theological text, Scivias

("Know the Ways"), Hildegard describes her struggle within:

Hildegard's Vita

was begun by Godfrey of Disibodenberg under Hildegard's supervision. It was between November 1147 and February 1148 at the synod in Trier that Pope Eugenus heard about Hildegard’s writings. It was from this that she received Papal approval to document her visions as revelations from the Holy Spirit giving her instant credence. (New York; Routledge, 2001) 5.

One of her better known works, Ordo Virtutum

(Play of the Virtues), is a morality play

. It is unsure when some of Hildegard’s compositions were composed, though the Ordo Virtutum is thought to have been composed as early as 1151. The morality play consists of monophonic

melodies for the Anima (human soul) and 16 Virtues. There is also one speaking part for the Devil. Scholars assert that the role of the Devil would have been played by Volmar, while Hildegard's nuns would have played the parts of Anima and the Virtues.

In addition to the Ordo Virtutum Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. The songs from the Symphonia are set to Hildegard’s own text and range from antiphons, hymns, and sequences, to responsories. Her music is described as monophonic

; that is, consisting of exactly one melodic line. Hildegard's compositional style is characterized by soaring melodies, often well outside of the normal range of chant at the time. Additionally, scholars such as Margot Fassler and Marianna Richert Pfau describe Hildegard's music as highly melismatic, often with recurrent melodic units, and also note her close attention to the relationship between music and text, which was a rare occurrence in monastic chant of the twelfth century. Hildegard of Bingen’s songs are left open for rhythmic interpretation because of the use of neume

s without a staff. The reverence for the Virgin Mary reflected in music shows how deeply influenced and inspired Hildegard of Bingen and her community were by the Virgin Mary and the saints.

The definition of ‘greenness’ is an earthly expression of the heavenly in an integrity that overcomes dualisms. This ‘greenness’ or power of life appears frequently in Hildegard’s works.

In addition to her music, Hildegard also wrote three books of visions, the first of which, her Scivias ("Know the Way"), was completed in 1151. Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits") and De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities", also known as Liber divinorum operum, "Book of Divine Works") followed. In these volumes, the last of which was completed when she was about 75, Hildegard first describes each vision, then interprets them through Biblical exegesis

. The narrative of her visions was richly decorated under her direction, with transcription assistance provided by the monk Volmar and nun Richardis. The book was celebrated in the Middle Ages

, in part because of the approval given to it by Pope Eugenius III

, and was later printed

in Paris in 1513.

Aside from her books of visions, Hildegard also wrote her Physica, a text on the natural sciences, as well as Causae et Curae. Hildegard of Bingen was well known for her healing powers involving practical application of tinctures, herbs, and precious stones. In both texts Hildegard describes the natural world around her, including the cosmos, animals, plants, stones, and minerals. She combined these elements with a theological notion ultimately derived from Genesis: all things put on earth are for the use of humans. She is particularly interested in the healing properties of plants, animals, and stones, though she also questions God's effect on man's health. One example of her healing powers was curing the blind with the use of Rhine water.

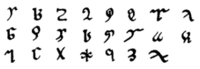

Hildegard also invented an alternative alphabet

Hildegard also invented an alternative alphabet

. The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin

, encompassing many invented, conflated and abridged words. Due to her inventions of words for her lyrics and a constructed script, many conlangers look upon her as a medieval precursor. Scholars believe that Hildegard used her Lingua Ignota

to increase solidarity among her nuns.

Hildegard's musical, literary, and scientific writings are housed primarily in two manuscripts: the Dendermonde manuscript and the Riesenkodex. The Dendermonde manuscript was copied under Hildegard's supervision at Rupertsberg, while the Riesencodex was copied in the century after Hildegard's death.

Hildegard's visionary writings maintain that virginity is the highest level of the spiritual life; however, she also wrote about secular life, including motherhood. In several of her texts, Hildegard describes the pleasure of the marital act.

Hildegard's visionary writings maintain that virginity is the highest level of the spiritual life; however, she also wrote about secular life, including motherhood. In several of her texts, Hildegard describes the pleasure of the marital act.

In addition, there are many instances, both in her letters and visions, that decry the misuse of carnal pleasures. She condemns the sins of same-sex couplings and masturbation. After confession, severe repentance expressed in fasting and bodily penance is needed to obtain forgiveness from God for such sins. For instance, in Scivias Book II Vision Six.78:

Human beings show forth God's creative power, and man and woman have complementary roles in the world.

Hildegard communicated with popes such as Eugene III

Hildegard communicated with popes such as Eugene III

and Anastasius IV, statesmen such as Abbot Suger

, German emperors such as Frederick I Barbarossa, and other notable figures such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux

, who advanced her work, at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier in 1147 and 1148. Hildegard of Bingen’s correspondence with many

people is an important element of her literary work because this is where we can see her speaking most directly to us.

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters. She traveled widely during her four preaching tours. She had several rather fanatic followers, including Guibert of Gembloux, who wrote frequently to Hildegard and eventually became her secretary after Volmar died in 1173. In addition, Hildegard influenced several monastic women of her time and the centuries that followed; in particular, she engaged in correspondence with another nearby visionary, Elisabeth of Schönau

.

Contributing to Christian European rhetorical traditions, she “authorized herself as a theologian” through alternative rhetorical arts. Hildegard was creative in her interpretation of theology. She believed that her monastery should not allow novices who were from a different class than nobility because it put them in an inferior position. She also stated that ‘woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman’. Due to church limitation on public, discursive rhetoric, the medieval rhetorical arts included: preaching, letter writing, poetry, and the encyclopedic tradition. Hildegard’s participation in these arts speaks to her significance as a female rhetorician, transcending bans on women’s social participation and interpretation of scriptures. The acceptance of public preaching by a woman,

even a well-connected abbess and acknowledged prophet does not fit the usual stereotype of this time. Her preaching was not limited to the monasteries. She even preached publically in 1160 in Germany. (New York: Routledge, 2001) 9. She conducted four preaching tours throughout Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in chapter houses and in public, mainly denouncing clerical corruption and calling for reform. Maddocks claims that it is likely she learned simple Latin, and the tenets of the Christian faith, but was not instructed in the Seven Liberal Arts

, which formed the basis of all education for the learned classes in the Middle Ages: the Trivium of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric plus the Quadrivium

of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. The correspondence she kept with the outside world both spiritual and social transgressed the cloister as a space of female confinement, and served to document Hildegard’s grand style and strict formatting of medieval letter writing. Recent scholars have asserted that Hildegard made a close association between music and the female body

in her musical compositions. The poetry and music of Hildegard’s Symphonia is concerned with the anatomy of female desire thus described as Sapphonic, or pertaining to Sappho, connecting her to a history of female rhetoricians.

In recent years, Hildegard has become of particular interest to feminist scholars. Her reference to herself as a member of the "weaker sex" and her rather constant belittling of women, though at first seemingly problematic, must be considered within the context of the patriarchal church hierarchy. Hildegard frequently referred to herself as an unlearned woman, completely incapable of Biblical exegesis. Such a statement on her part, however, worked to her advantage because it made her statements that all of her writings and music came from visions of the Divine more believable, therefore giving Hildegard the authority to speak in a time and place where few women were permitted a voice. Hildegard used her voice to condemn church practices she disagreed with, in particular simony

.

Hildegard has also become a figure of reverence within the contemporary New Age movement, mostly due to her holistic and natural view of healing, as well as her status as a mystic. She was the inspiration for Dr. Gottfried Hertzka's "Hildegard-Medicine", and is the namesake for June Boyce-Tillman's Hildegard Network, a healing center that focuses on a holistic approach to wellness and brings

together people interested in exploring the links between spirituality, the arts, and healing,. Hildegard's reincarnation has been debated since 1924 when Austrian mystic Rudolf Steiner

lectured that a nun of her description was the past life of Russian poet Vladimir Soloviev

, whose Sophianic visions are often compared to Hildegard. Sophiologist Robert Powell writes that hermetic astrology proves the match, and artist mystic Carl Schroeder claims to be in the lineage of Hildegard with the support and validation of reincarnation author Walter Semkiw.

Before Hildegard’s death, a problem arose with the clergy of Mainz. A man buried in Rupertsburg had died after excommunication from the Church. Therefore, the clergy wanted to remove his body from the sacred ground. Hildegard did not accept this idea, replying that it was a sin and that the man had been reconciled to the church at the time of his death. On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.

Hildegard was one of the first persons for whom the canonization

process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization were not completed, and she remained at the level of her beatification

. Hildegard's name was nonetheless taken up in the Roman Martyrology

at the end of the sixteenth century. Her feast day is 17 September. Numerous popes have referred to Hildegard as a saint, including Pope John Paul II

and Pope Benedict XVI

. Hildegard’s Parish and Pilgrimage Church house the relic

s of Hildegard, including an altar

encasing her remains, in Eibingen near Rüdesheim.

Hildegard of Bingen also appears in the calendar of saints

in various Anglican

churches. In the Church of England

she is commemorated on 17 September.

In space, she is commemorated by the asteroid

898 Hildegard

.

Hildegard has been portrayed on film by Patricia Routledge (Keeping Up Appearances) in a dramatized BBC biographical documentary called "Hildegard Von Bingen In Portrait: Ordo Virtutum."

The film Vision - From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen

, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, premiered in Europe in 2009 and in the United States in 2010. Hildegard is played by Barbara Sukowa

.

The 2013 film Goddess Exhaling recounts the story of a young Southern California women who, leaving her dance class, encounters the spirit of Hildegard of Bingen in a health food store and is prevailed upon to bring the abbess's teachings to a yoga and organic food retreat.

On Hildegard's illuminations

Background reading

Mysticism

Mysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

, Benedictine

Benedictine

Benedictine refers to the spirituality and consecrated life in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century for the cenobitic communities he founded in central Italy. The most notable of these is Monte Cassino, the first monastery founded by Benedict...

abbess

Abbess

An abbess is the female superior, or mother superior, of a community of nuns, often an abbey....

, visionary

Visionary

Defined broadly, a visionary, is one who can envision the future. For some groups this can involve the supernatural or drugs.The visionary state is achieved via meditation, drugs, lucid dreams, daydreams, or art. One example is Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th century artist/visionary and Catholic saint...

, and polymath

Polymath

A polymath is a person whose expertise spans a significant number of different subject areas. In less formal terms, a polymath may simply be someone who is very knowledgeable...

. Elected a magistra by her fellow nuns in 1136, she founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg

Rupertsberg

Rupertsberg is a crag at the confluence of the Nahe River and the Rhine, in Bingen am Rhein. It is named for Saint Rupert of Bingen, son of Bertha of Bingen. It is notable as the site of the first convent founded by Saint Hildegard of Bingen, in 1150, after leaving the monastery at Disibodenberg...

in 1150 and Eibingen

Eibingen

Eibingen, now a part of Rüdesheim am Rhein, Hessen, Germany is the location of Eibingen Abbey, the Benedictine monastery founded by Hildegard of Bingen in 1165 ....

in 1165. One of her works as a composer, the Ordo Virtutum

Ordo Virtutum

Ordo Virtutum is an allegorical morality play, or liturgical drama, by Hildegard of Bingen, composed c. 1151...

, is an early example of liturgical drama.

She wrote theological, botanical and medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs, poems, and arguably the oldest surviving morality play

Morality play

The morality play is a genre of Medieval and early Tudor theatrical entertainment. In their own time, these plays were known as "interludes", a broader term given to dramas with or without a moral theme. Morality plays are a type of allegory in which the protagonist is met by personifications of...

, while supervising brilliant miniature Illuminations.

Biography

Vision (religion)

In spirituality, a vision is something seen in a dream, trance, or ecstasy, especially a supernatural appearance that conveys a revelation.Visions generally have more clarity than dreams, but traditionally fewer psychological connotations...

.

Perhaps due to Hildegard's visions, or as a method of political positioning, Hildegard's parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, offered her as a tithe

Tithe

A tithe is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques, or stocks, whereas historically tithes were required and paid in kind, such as agricultural products...

to the church. The date of Hildegard's enclosure in the church is contentious. Her Vita tells us she was enclosed with an older nun, Jutta, at the age of eight. However, Jutta's enclosure date is known to be in 1112, at which time Hildegard would have been fourteen. Some scholars speculate that Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta

Jutta von Sponheim

Countess Jutta von Sponheim was the youngest of four noblewomen who were born into affluent surroundings in what is currently the Rhineland-Palatinate...

, the daughter of Count Stephan II of Sponheim, at the age of eight, before the two women were enclosed together six years later. There is no written record of the twenty-four years of Hildegard's life that she was in the convent together with Jutta. It is possible that Hildegard could have been a chantress and a worker in the herbarium and infirmarium. In any case, Hildegard and Jutta were enclosed at Disibodenberg

Disibodenberg

thumb|right|Disibodenberg todaythumb|Disibodenberg ruinsthumb|Disibodenberg ruinsthumb|Disibodenberg pictureDisibodenberg is a monastery ruin in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It was founded by Saint Disibod. Hildegard of Bingen, who wrote Disibod's biography "Vita Sancti Disibodi", also lived in...

in the Palatinate Forest in what is now Germany. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the enclosure. Hildegard also tells us that Jutta taught her to read and write, but that she was unlearned and therefore incapable of teaching Hildegard Biblical interpretation. Hildegard and Jutta most likely prayed, meditated, read scriptures such as the psalter, and did some sort of handwork during the hours of the Divine Office. This also might have been a time when Hildegard learned how to play the ten-stringed psaltery

Psaltery

A psaltery is a stringed musical instrument of the harp or the zither family. The psaltery of Ancient Greece dates from at least 2800 BC, when it was a harp-like instrument...

. Volmar, a frequent visitor, may have taught Hildegard simple psalm notation. The time she studied music could also have been the beginning of the compositions she would later create.

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as "magistra" of her sister community by her fellow nuns. Abbot Kuno, the Abbot of Disibodenberg, also asked Hildegard to be Prioress. Hildegard, however, wanted more independence for herself and her nuns and asked Abbot Kuno to allow them to move to Rupertsberg

Rupertsberg

Rupertsberg is a crag at the confluence of the Nahe River and the Rhine, in Bingen am Rhein. It is named for Saint Rupert of Bingen, son of Bertha of Bingen. It is notable as the site of the first convent founded by Saint Hildegard of Bingen, in 1150, after leaving the monastery at Disibodenberg...

. This was to be a move towards poverty from a stone complex that was well established to a temporary dwelling place. (New York: Routledge, 2001), 6. When the abbot declined Hildegard's proposition, Hildegard went over his head and received the approval of Archbishop Henry I of Mainz. Abbot Kuno did not relent, however, until Hildegard was stricken by an illness that kept her paralyzed and unable to move from her bed, an event that she attributed to God's unhappiness at her not following his orders to move her nuns to Rupertsberg. It was only when the Abbot himself could not move Hildegard that he decided to grant the nuns their own monastery. Hildegard and about twenty nuns thus moved to the St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar served as provost, as well as Hildegard's confessor and scribe. In 1165 Hildegard founded a second convent for her nuns at Eibingen

Eibingen Abbey

Eibingen Abbey is a community of Benedictine nuns in Eibingen near Rüdesheim in Hesse, Germany.The original community was founded in 1165 by Hildegard von Bingen...

.

Hildegard says that she first saw "The Shade of the Living Light" at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions. She used the term 'visio' to this feature of her experience, and recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Hildegard was hesitant to share her visions, confiding only to Jutta

Jutta

The feminine name Jutta is the German form of Judith. In German it is pronounced Yutta -- the u is pronounced like the u in "put." It could also derive from the Germanic name Eutha meaning "mankind, child, descendant"....

, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, secretary. Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions, and in 1141, at the age of 42, Hildegard received a vision she believed to be an instruction from God, to "write down that which you see and hear." Still hesitant to record her visions, Hildegard became physically ill. The illustrations recorded in the book of Scivias were visions that Hildegard experienced, causing her great

suffering and tribulations. In her first theological text, Scivias

Scivias

Scivias is an illustrated work by Hildegard von Bingen, completed in 1151 or 1152, describing 26 religious visions she experienced. It is the first of three works that she wrote describing her visions, the others being Liber vitae meritorum and De operatione Dei...

("Know the Ways"), Hildegard describes her struggle within:

But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [the nun Richardis von Stade] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above, I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition; and, raising myself from illness by the strength I received, I brought this work to a close – though just barely – in ten years. [...] And I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, 'Cry out therefore, and write thus!'

Hildegard's Vita

Hagiography

Hagiography is the study of saints.From the Greek and , it refers literally to writings on the subject of such holy people, and specifically to the biographies of saints and ecclesiastical leaders. The term hagiology, the study of hagiography, is also current in English, though less common...

was begun by Godfrey of Disibodenberg under Hildegard's supervision. It was between November 1147 and February 1148 at the synod in Trier that Pope Eugenus heard about Hildegard’s writings. It was from this that she received Papal approval to document her visions as revelations from the Holy Spirit giving her instant credence. (New York; Routledge, 2001) 5.

Works

Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Church has led to a great deal of popular interest in Hildegard, particularly her music. Between 70 and 80 compositions have survived, which is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. Hildegard left behind over 100 letters, 72 songs, 70 poems, and 9 books.One of her better known works, Ordo Virtutum

Ordo Virtutum

Ordo Virtutum is an allegorical morality play, or liturgical drama, by Hildegard of Bingen, composed c. 1151...

(Play of the Virtues), is a morality play

Morality play

The morality play is a genre of Medieval and early Tudor theatrical entertainment. In their own time, these plays were known as "interludes", a broader term given to dramas with or without a moral theme. Morality plays are a type of allegory in which the protagonist is met by personifications of...

. It is unsure when some of Hildegard’s compositions were composed, though the Ordo Virtutum is thought to have been composed as early as 1151. The morality play consists of monophonic

Monophony

In music, monophony is the simplest of textures, consisting of melody without accompanying harmony. This may be realized as just one note at a time, or with the same note duplicated at the octave . If the entire melody is sung by two voices or a choir with an interval between the notes or in...

melodies for the Anima (human soul) and 16 Virtues. There is also one speaking part for the Devil. Scholars assert that the role of the Devil would have been played by Volmar, while Hildegard's nuns would have played the parts of Anima and the Virtues.

In addition to the Ordo Virtutum Hildegard composed many liturgical songs that were collected into a cycle called the Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. The songs from the Symphonia are set to Hildegard’s own text and range from antiphons, hymns, and sequences, to responsories. Her music is described as monophonic

Monophony

In music, monophony is the simplest of textures, consisting of melody without accompanying harmony. This may be realized as just one note at a time, or with the same note duplicated at the octave . If the entire melody is sung by two voices or a choir with an interval between the notes or in...

; that is, consisting of exactly one melodic line. Hildegard's compositional style is characterized by soaring melodies, often well outside of the normal range of chant at the time. Additionally, scholars such as Margot Fassler and Marianna Richert Pfau describe Hildegard's music as highly melismatic, often with recurrent melodic units, and also note her close attention to the relationship between music and text, which was a rare occurrence in monastic chant of the twelfth century. Hildegard of Bingen’s songs are left open for rhythmic interpretation because of the use of neume

Neume

A neume is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation. The word is a Middle English corruption of the ultimately Ancient Greek word for breath ....

s without a staff. The reverence for the Virgin Mary reflected in music shows how deeply influenced and inspired Hildegard of Bingen and her community were by the Virgin Mary and the saints.

The definition of ‘greenness’ is an earthly expression of the heavenly in an integrity that overcomes dualisms. This ‘greenness’ or power of life appears frequently in Hildegard’s works.

In addition to her music, Hildegard also wrote three books of visions, the first of which, her Scivias ("Know the Way"), was completed in 1151. Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits") and De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities", also known as Liber divinorum operum, "Book of Divine Works") followed. In these volumes, the last of which was completed when she was about 75, Hildegard first describes each vision, then interprets them through Biblical exegesis

Exegesis

Exegesis is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text, especially a religious text. Traditionally the term was used primarily for exegesis of the Bible; however, in contemporary usage it has broadened to mean a critical explanation of any text, and the term "Biblical exegesis" is used...

. The narrative of her visions was richly decorated under her direction, with transcription assistance provided by the monk Volmar and nun Richardis. The book was celebrated in the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

, in part because of the approval given to it by Pope Eugenius III

Pope Eugene III

Pope Blessed Eugene III , born Bernardo da Pisa, was Pope from 1145 to 1153. He was the first Cistercian to become Pope.-Early life:...

, and was later printed

Editio princeps

In classical scholarship, editio princeps is a term of art. It means, roughly, the first printed edition of a work that previously had existed only in manuscripts, which could be circulated only after being copied by hand....

in Paris in 1513.

Aside from her books of visions, Hildegard also wrote her Physica, a text on the natural sciences, as well as Causae et Curae. Hildegard of Bingen was well known for her healing powers involving practical application of tinctures, herbs, and precious stones. In both texts Hildegard describes the natural world around her, including the cosmos, animals, plants, stones, and minerals. She combined these elements with a theological notion ultimately derived from Genesis: all things put on earth are for the use of humans. She is particularly interested in the healing properties of plants, animals, and stones, though she also questions God's effect on man's health. One example of her healing powers was curing the blind with the use of Rhine water.

Constructed script

A constructed script is a new writing system specifically created by an individual or group, rather than having evolved as part of a language or culture like a natural script...

. The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, encompassing many invented, conflated and abridged words. Due to her inventions of words for her lyrics and a constructed script, many conlangers look upon her as a medieval precursor. Scholars believe that Hildegard used her Lingua Ignota

Lingua Ignota

A Lingua Ignota was described by the 12th century abbess of Rupertsberg, Hildegard of Bingen, who apparently used it for mystical purposes...

to increase solidarity among her nuns.

Hildegard's musical, literary, and scientific writings are housed primarily in two manuscripts: the Dendermonde manuscript and the Riesenkodex. The Dendermonde manuscript was copied under Hildegard's supervision at Rupertsberg, while the Riesencodex was copied in the century after Hildegard's death.

In addition, there are many instances, both in her letters and visions, that decry the misuse of carnal pleasures. She condemns the sins of same-sex couplings and masturbation. After confession, severe repentance expressed in fasting and bodily penance is needed to obtain forgiveness from God for such sins. For instance, in Scivias Book II Vision Six.78:

God united man and woman, thus joining the strong to the weak, that each might sustain the other. But these perverted adulterers change their virile strength into perverse weakness, rejecting the proper male and female roles, and in their wickedness they shamefully follow Satan, who in his pride sought to split and divide Him Who is indivisible. They create in themselves by their wicked deeds a strange and perverse adultery, and so appear polluted and shameful in my sight...

...a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile in My (God's) sight, and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed...

...And men who touch their own genital organ and emit their semen seriously imperil their souls, for they excite themselves to distraction; they appear to Me as impure animals devouring their own whelps...

...When a person feels himself disturbed by bodily stimulation let him run to the refuge of continence, and seize the shield of chastity, and thus defend himself from uncleanness. (translation by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop)

Human beings show forth God's creative power, and man and woman have complementary roles in the world.

...When God looked upon the human countenance, God was exceedingly pleased. For had not God created humanity according to the divine image and likeness? Human beings were to announce all God's wondrous works by means of their tongues that were endowed with reason. For humanity is God's complete work....

Man and woman are in this way so involved with each other that one of them is the work of the other. Without woman, man could not be called man; without man, woman could not be named woman. Thus woman is the work of man, while man is a sight full of consolation for woman. Neither of them could henceforth live without the other. Man is in this connection an indication of the Godhead while woman is an indication of the humanity of God's Son.

Significance

Pope Eugene III

Pope Blessed Eugene III , born Bernardo da Pisa, was Pope from 1145 to 1153. He was the first Cistercian to become Pope.-Early life:...

and Anastasius IV, statesmen such as Abbot Suger

Abbot Suger

Suger was one of the last Frankish abbot-statesmen, an historian, and the influential first patron of Gothic architecture....

, German emperors such as Frederick I Barbarossa, and other notable figures such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O.Cist was a French abbot and the primary builder of the reforming Cistercian order.After the death of his mother, Bernard sought admission into the Cistercian order. Three years later, he was sent to found a new abbey at an isolated clearing in a glen known as the Val...

, who advanced her work, at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier in 1147 and 1148. Hildegard of Bingen’s correspondence with many

people is an important element of her literary work because this is where we can see her speaking most directly to us.

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters. She traveled widely during her four preaching tours. She had several rather fanatic followers, including Guibert of Gembloux, who wrote frequently to Hildegard and eventually became her secretary after Volmar died in 1173. In addition, Hildegard influenced several monastic women of her time and the centuries that followed; in particular, she engaged in correspondence with another nearby visionary, Elisabeth of Schönau

Elizabeth of Schönau

Elizabeth of Schönau was a German Benedictine visionary. When her writings were published, the title of "Saint" was added to her name. She was never canonized, but in 1584 her name was entered in the Roman Martyrology and has remained there...

.

Contributing to Christian European rhetorical traditions, she “authorized herself as a theologian” through alternative rhetorical arts. Hildegard was creative in her interpretation of theology. She believed that her monastery should not allow novices who were from a different class than nobility because it put them in an inferior position. She also stated that ‘woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman’. Due to church limitation on public, discursive rhetoric, the medieval rhetorical arts included: preaching, letter writing, poetry, and the encyclopedic tradition. Hildegard’s participation in these arts speaks to her significance as a female rhetorician, transcending bans on women’s social participation and interpretation of scriptures. The acceptance of public preaching by a woman,

even a well-connected abbess and acknowledged prophet does not fit the usual stereotype of this time. Her preaching was not limited to the monasteries. She even preached publically in 1160 in Germany. (New York: Routledge, 2001) 9. She conducted four preaching tours throughout Germany, speaking to both clergy and laity in chapter houses and in public, mainly denouncing clerical corruption and calling for reform. Maddocks claims that it is likely she learned simple Latin, and the tenets of the Christian faith, but was not instructed in the Seven Liberal Arts

Liberal arts

The term liberal arts refers to those subjects which in classical antiquity were considered essential for a free citizen to study. Grammar, Rhetoric and Logic were the core liberal arts. In medieval times these subjects were extended to include mathematics, geometry, music and astronomy...

, which formed the basis of all education for the learned classes in the Middle Ages: the Trivium of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric plus the Quadrivium

Quadrivium

The quadrivium comprised the four subjects, or arts, taught in medieval universities, after teaching the trivium. The word is Latin, meaning "the four ways" , and its use for the 4 subjects has been attributed to Boethius or Cassiodorus in the 6th century...

of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. The correspondence she kept with the outside world both spiritual and social transgressed the cloister as a space of female confinement, and served to document Hildegard’s grand style and strict formatting of medieval letter writing. Recent scholars have asserted that Hildegard made a close association between music and the female body

in her musical compositions. The poetry and music of Hildegard’s Symphonia is concerned with the anatomy of female desire thus described as Sapphonic, or pertaining to Sappho, connecting her to a history of female rhetoricians.

In recent years, Hildegard has become of particular interest to feminist scholars. Her reference to herself as a member of the "weaker sex" and her rather constant belittling of women, though at first seemingly problematic, must be considered within the context of the patriarchal church hierarchy. Hildegard frequently referred to herself as an unlearned woman, completely incapable of Biblical exegesis. Such a statement on her part, however, worked to her advantage because it made her statements that all of her writings and music came from visions of the Divine more believable, therefore giving Hildegard the authority to speak in a time and place where few women were permitted a voice. Hildegard used her voice to condemn church practices she disagreed with, in particular simony

Simony

Simony is the act of paying for sacraments and consequently for holy offices or for positions in the hierarchy of a church, named after Simon Magus , who appears in the Acts of the Apostles 8:9-24...

.

Hildegard has also become a figure of reverence within the contemporary New Age movement, mostly due to her holistic and natural view of healing, as well as her status as a mystic. She was the inspiration for Dr. Gottfried Hertzka's "Hildegard-Medicine", and is the namesake for June Boyce-Tillman's Hildegard Network, a healing center that focuses on a holistic approach to wellness and brings

together people interested in exploring the links between spirituality, the arts, and healing,. Hildegard's reincarnation has been debated since 1924 when Austrian mystic Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner was an Austrian philosopher, social reformer, architect, and esotericist. He gained initial recognition as a literary critic and cultural philosopher...

lectured that a nun of her description was the past life of Russian poet Vladimir Soloviev

Vladimir Solovyov (philosopher)

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov was a Russian philosopher, poet, pamphleteer, literary critic, who played a significant role in the development of Russian philosophy and poetry at the end of the 19th century...

, whose Sophianic visions are often compared to Hildegard. Sophiologist Robert Powell writes that hermetic astrology proves the match, and artist mystic Carl Schroeder claims to be in the lineage of Hildegard with the support and validation of reincarnation author Walter Semkiw.

Before Hildegard’s death, a problem arose with the clergy of Mainz. A man buried in Rupertsburg had died after excommunication from the Church. Therefore, the clergy wanted to remove his body from the sacred ground. Hildegard did not accept this idea, replying that it was a sin and that the man had been reconciled to the church at the time of his death. On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.

Hildegard was one of the first persons for whom the canonization

Canonization

Canonization is the act by which a Christian church declares a deceased person to be a saint, upon which declaration the person is included in the canon, or list, of recognized saints. Originally, individuals were recognized as saints without any formal process...

process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization were not completed, and she remained at the level of her beatification

Beatification

Beatification is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a dead person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in his or her name . Beatification is the third of the four steps in the canonization process...

. Hildegard's name was nonetheless taken up in the Roman Martyrology

Roman Martyrology

The Roman Martyrology is the official martyrology of the Roman Rite of the Roman Catholic Church. It provides an extensive but not exhaustive list of the saints recognized by the Church.-History:...

at the end of the sixteenth century. Her feast day is 17 September. Numerous popes have referred to Hildegard as a saint, including Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

and Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI

Benedict XVI is the 265th and current Pope, by virtue of his office of Bishop of Rome, the Sovereign of the Vatican City State and the leader of the Catholic Church as well as the other 22 sui iuris Eastern Catholic Churches in full communion with the Holy See...

. Hildegard’s Parish and Pilgrimage Church house the relic

Relic

In religion, a relic is a part of the body of a saint or a venerated person, or else another type of ancient religious object, carefully preserved for purposes of veneration or as a tangible memorial...

s of Hildegard, including an altar

Altar

An altar is any structure upon which offerings such as sacrifices are made for religious purposes. Altars are usually found at shrines, and they can be located in temples, churches and other places of worship...

encasing her remains, in Eibingen near Rüdesheim.

Hildegard of Bingen also appears in the calendar of saints

Calendar of saints

The calendar of saints is a traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the feast day of said saint...

in various Anglican

Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is an international association of national and regional Anglican churches in full communion with the Church of England and specifically with its principal primate, the Archbishop of Canterbury...

churches. In the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

she is commemorated on 17 September.

In space, she is commemorated by the asteroid

Asteroid

Asteroids are a class of small Solar System bodies in orbit around the Sun. They have also been called planetoids, especially the larger ones...

898 Hildegard

898 Hildegard

-External links:*...

.

See also

- Bibliography of Hildegard of BingenBibliography of Hildegard of Bingen-Original Latin works:*Carlevaris, Angela, ed. Liber vite meritorum . CCCM 90. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1995.*Derolez, Albert, ed. Guibert of Gembloux, Epistolae. CCCM 66-66a. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1988, 1989....

- Discography of Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard has been portrayed on film by Patricia Routledge (Keeping Up Appearances) in a dramatized BBC biographical documentary called "Hildegard Von Bingen In Portrait: Ordo Virtutum."

The film Vision - From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen

Vision - From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen

Vision is a 2009 German film directed by Margarethe von Trotta.-Plot:In Vision, New German Cinema auteur Margarethe von Trotta tells the story of Hildegard von Bingen the famed 12th century Benedictine nun, Christian mystic,...

, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, premiered in Europe in 2009 and in the United States in 2010. Hildegard is played by Barbara Sukowa

Barbara Sukowa

Barbara Sukowa is a German theatre and film actress.- Work :Sukowa's stage debut was in Berlin in 1971, in a production of Peter Handke's Der Ritt über den Bodensee. Günter Beelitz invited her to join the ensemble of the Darmstädter National Theatre in the same year...

.

The 2013 film Goddess Exhaling recounts the story of a young Southern California women who, leaving her dance class, encounters the spirit of Hildegard of Bingen in a health food store and is prevailed upon to bring the abbess's teachings to a yoga and organic food retreat.

Further reading

General commentary- Burnett, Charles and Peter Dronke, eds. Hildegard of Bingen: The Context of Her Thought and Art. The Warburg Colloquia. London: The University of London, 1998.

- Cherewatuk, Karen and Ulrike Wiethaus, eds. Dear Sister: Medieval Women and the Epistolary Genre. Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

- Davidson, Audrey Ekdahl. The Ordo Virtutum of Hildegard of Bingen: Critical Studies. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1992. ISBN 1-879288-17-6

- Dronke, Peter. Women Writers of the Middle Ages: A Critical Study of Texts from Perpetua to Marguerite Porete. 1984. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Flanagan, Sabina. Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-7607-1361-8

- King-Lenzmeier, Anne H. Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2001.

- Newman, Barbara. Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Newman, Barbara, ed. Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World. Berkeley: University of California, 1998.

- Pernoud, Régine. Hildegard of Bingen: Inspired Conscience of the Twelfth Century. Translated by Paul Duggan. NY: Marlowe & Co., 1998.

- Schipperges, Heinrich. The World of Hildegard of Bingen: Her Life, Times, and Visions. Trans. John Cumming. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1999.

- Wilson, Katharina. Medieval Women Writers. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1984.

On Hildegard's illuminations

- Fox, Matthew. Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen. Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Company, 1985. ISBN 1-879181-97-5

- Harris, Anne Sutherland and Linda NochlinLinda NochlinLinda Nochlin is an American art historian, university professor and writer. She is considered to be a leader in feminist art history studies. She is best known as a proponent of the question "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?"...

, Women Artists: 1550–1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1976. ISBN 0-394-73326-6

Background reading

- Barber, Richard. Bestiary: MS Bodley 764. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

- Boyce-Tillman, June. The Creative Spirit: Harmonious Living with Hildegard of Bingen, Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-8192-1882-0

- Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedict. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2006.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: the Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

- Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990. ISBN 0-500-20354-7

- Constable, Giles Constable. The Reformation of the Twelfth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Dronke, Peter, ed. A History of Twelfth-Century Western Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Holweck, the Rt. Reverend Frederick G.Frederick George HolweckFrederick George Holweck was a German-American Roman Catholic priest and scholar, hagiographer and church historian.-Life:...

, A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints, with a General Introduction on Hagiology. 1924. Detroit: Omnigraphics, 1990. - Lachman, Barbara. The Journal of Hildegard of Bingen: A Novel. New York: Crown, 1993.

- Lachman, Barbara. Hildegard: The Last Year. Boston: Shambhala, 1997.

- McBrien, Richard. Lives of the Saints: From Mary and St. Francis of Assisi to John XXIII and Mother Teresa. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003.

- McKnight, Scot. The Real Mary: Why Evangelical Christians Can Embrace the Mother of Jesus. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2006.

- Newman, Barbara trans. Symphonia: A Critical Edition of the "Symphonia armoniae celestium revelationum. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1988.

- Newman, Barbara. God and the Goddesses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1911-2

- O’Donohue, John. Anam Ċara. New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

- Ohanneson, Joan. Scarlet Music. Hildegard of Bingen: A Novel. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1997.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Sacks, Oliver. Migraine: Understanding a Common Disorder. 1985. Reprint. London: Vintage Books, 1999.

- Santos Paz, José Carlos, ed. La Obra de Gebenón de Eberbach. Firenze: SISMEL-Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2004.

- Sherman, Bernard D. “‘Mistaking the Tail for the Comet’: An Interview with Christopher

- Silvas, Anna. Jutta and Hildegard: The Biographical Sources. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-271-01954-9

- Sweet, Victoria. "Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine." Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 1999, 73:381–403.

- Sweet, Victoria. "Rooted in the Earth, Rooted in the Sky: Hildegard of Bingen and Premodern Medicine." New York: Routledge Press, 2006. ISBN 0-415-97634-0

- Ulrich, Ingeborg. Hildegard of Bingen: Mystic, Healer, Companion of the Angels. Trans. Linda M. Maloney. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1993.

- Ward, Benedicta. Miracles and the Medieval Mind. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1987.

- Weeks, Andrew. German mysticism from Hildegard of Bingen to Ludwig Wittgenstein : a literary and intellectual history. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993. ISBN 0-7914-1419-1

External links

- Hildegard Center for the Arts, A Faith Based Fine Arts Center in Lincoln Nebraska

- International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies

- A Hildegard FAQ Sheet

- Hildegard Von Bingen

- Hildegard of Bingen Documents, History, Sites to see today, etc.

- Source

- Discography

- Biography and Prayers of Hildegard

- Another discography

- Church of St. Hildegard in Eibingen, Germany with information about Hildegard von Bingen and the Eibinger Hildegardisshrine

- The Reconstruction of the monastery on the Rupertsberg

- Young, Abigail Ann. Translations from Rupert, Hildegard, and Guibert of Gembloux. 1999. 27 March 2006.

- McGuire, K. Christian. Symphonia Caritatis: The Cistercian Chants of Hildegard von Bingen. 2007. 14 July 2007.

- * From Katya Sanna's blog

- Women's Biography: Hildegard of Bingen, contains several letters sent and received by Hildegard.

- "Brooklyn Museum: Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Place Setting: Hildegarde of Bingen", describes the Hildegarde Place Setting in Judy Chicago's work called "The Dinner Party".