History of Biotechnology

Encyclopedia

Biotechnology

Biotechnology is a field of applied biology that involves the use of living organisms and bioprocesses in engineering, technology, medicine and other fields requiring bioproducts. Biotechnology also utilizes these products for manufacturing purpose...

is the application of scientific and engineering principles to the processing of materials by biological agents to provide goods and services. From its inception, biotechnology has maintained a close relationship with society. Although now most often associated with the development of remarkable drug

Drug

A drug, broadly speaking, is any substance that, when absorbed into the body of a living organism, alters normal bodily function. There is no single, precise definition, as there are different meanings in drug control law, government regulations, medicine, and colloquial usage.In pharmacology, a...

s, historically biotechnology has been principally associated with food, addressing such issues as malnutrition

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is the condition that results from taking an unbalanced diet in which certain nutrients are lacking, in excess , or in the wrong proportions....

and famine

Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including crop failure, overpopulation, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every continent in the world has...

. The history of biotechnology

Biotechnology

Biotechnology is a field of applied biology that involves the use of living organisms and bioprocesses in engineering, technology, medicine and other fields requiring bioproducts. Biotechnology also utilizes these products for manufacturing purpose...

begins with zymotechnology, which commenced with a focus on brewing

Brewing

Brewing is the production of beer through steeping a starch source in water and then fermenting with yeast. Brewing has taken place since around the 6th millennium BCE, and archeological evidence suggests that this technique was used in ancient Egypt...

techniques for beer. By World War I, however, zymotechnology would expand to tackle larger industrial issues, and the potential of industrial fermentation

Industrial fermentation

Industrial fermentation is the intentional use of fermentation by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi to make products useful to humans. Fermented products have applications as food as well as in general industry.- Food fermentation :...

gave rise to biotechnology.However, both the single-cell protein and gasohol projects failed to progress due to varying issues including public resistance, a changing economic scene, and shifts in political power.

Yet the formation of a new field, genetic engineering

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

, would soon bring biotechnology to the forefront of science in society, and the intimate relationship between the scientific community, the public, and the government would ensue. These debates gained exposure in 1975 at the Asilomar Conference, where Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was just 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and...

was the most outspoken supporter for this emerging field in biotechnology. By as early as 1978, with the synthesis of synthetic human insulin

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

, Lederberg's claims would prove valid, and the biotechnology industry grew rapidly. Each new scientific advance became a media event designed to capture public support, and by the 1980s, biotechnology grew into a promising real industry. In 1988, only five proteins from genetically engineered cells had been approved as drugs by the United States Food and Drug Administration

Food and Drug Administration

The Food and Drug Administration is an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, one of the United States federal executive departments...

(FDA), but this number would skyrocket to over 125 by the end of the 1990s.

The field of genetic engineering remains a heated topic of discussion in today's society with the advent of gene therapy

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is the insertion, alteration, or removal of genes within an individual's cells and biological tissues to treat disease. It is a technique for correcting defective genes that are responsible for disease development...

, stem cell research, cloning

Cloning

Cloning in biology is the process of producing similar populations of genetically identical individuals that occurs in nature when organisms such as bacteria, insects or plants reproduce asexually. Cloning in biotechnology refers to processes used to create copies of DNA fragments , cells , or...

, and genetically-modified food

Genetically modified food

Genetically modified foods are foods derived from genetically modified organisms . Genetically modified organisms have had specific changes introduced into their DNA by genetic engineering techniques...

. While it seems only natural nowadays to link pharmaceutical drugs as solutions to health and societal problems, this relationship of biotechnology serving social needs began centuries ago.

Origins of biotechnology

Biotechnology arose from the field of zymotechnology, which began as a search for a better understanding of industrial fermentation, particularly beer. Beer was an important industrial, and not just social, commodity. In late 19th century Germany, brewingBrewing

Brewing is the production of beer through steeping a starch source in water and then fermenting with yeast. Brewing has taken place since around the 6th millennium BCE, and archeological evidence suggests that this technique was used in ancient Egypt...

contributed as much to the gross national product as steel, and taxes on alcohol proved to be significant sources of revenue to the government. In the 1860s, institutes and remunerative consultancies were dedicated to the technology of brewing. The most famous was the private Carlsberg Institute, founded in 1875, which employed Emil Christian Hansen, who pioneered the pure yeast process for the reliable production of consistent beer. Less well known were private consultancies that advised the brewing industry. One of these, the Zymotechnic Institute, was established in Chicago by the German-born chemist John Ewald Siebel.

The heyday and expansion of zymotechnology came in World War I in response to industrial needs to support the war. Max Delbruck

Max Delbrück

Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück was a German-American biophysicist and Nobel laureate.-Biography:Delbrück was born in Berlin, German Empire...

grew yeast on an immense scale during the war to meet 60 percent of Germany's animal feed needs. Compounds of another fermentation product, lactic acid

Lactic acid

Lactic acid, also known as milk acid, is a chemical compound that plays a role in various biochemical processes and was first isolated in 1780 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Lactic acid is a carboxylic acid with the chemical formula C3H6O3...

, made up for a lack of hydraulic fluid, glycerol

Glycerol

Glycerol is a simple polyol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is widely used in pharmaceutical formulations. Glycerol has three hydroxyl groups that are responsible for its solubility in water and its hygroscopic nature. The glycerol backbone is central to all lipids...

. On the Allied side the Russian chemist Chaim Weizmann used starch to eliminate Britain's shortage of acetone

Acetone

Acetone is the organic compound with the formula 2CO, a colorless, mobile, flammable liquid, the simplest example of the ketones.Acetone is miscible with water and serves as an important solvent in its own right, typically as the solvent of choice for cleaning purposes in the laboratory...

, a key raw material in explosives, by fermenting maize to acetone. The industrial potential of fermentation

Industrial fermentation

Industrial fermentation is the intentional use of fermentation by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi to make products useful to humans. Fermented products have applications as food as well as in general industry.- Food fermentation :...

was outgrowing its traditional home in brewing, and "zymotechnology" soon gave way to "biotechnology."

With food shortages spreading and resources fading, some dreamed of a new industrial solution. The Hungarian Karl Ereky

Karl Ereky

Karl Ereky born as Wittmann Károly and also known as Ereky Károly was an Hungarian Agricultural engineer.-Early life:Ereky was born on October 18, 1878 in Esztergom, Hungary as Wittmann Károly. In 1893 he changed his name to Ereky. He had three brothers Ereky Jenő, Ereky Ferenc and Ereky István....

coined the word "biotechnology" in Hungary during 1919 to describe a technology based on converting raw materials into a more useful product. He built a slaughterhouse for a thousand pigs and also a fattening farm with space for 50,000 pigs, raising over 100,000 pigs a year. The enterprise was enormous, becoming one of the largest and most profitable meat and fat operations in the world. In a book entitled Biotechnologie, Ereky further developed a theme that would be reiterated through the 20th century: biotechnology could provide solutions to societal crises, such as food and energy shortages. For Ereky, the term "biotechnologie" indicated the process by which raw materials could be biologically upgraded into socially useful products.

This catchword spread quickly after the First World War, as "biotechnology" entered German dictionaries and was taken up abroad by business-hungry private consultancies as far away as the United States. In Chicago, for example, the coming of prohibition

Prohibition

Prohibition of alcohol, often referred to simply as prohibition, is the practice of prohibiting the manufacture, transportation, import, export, sale, and consumption of alcohol and alcoholic beverages. The term can also apply to the periods in the histories of the countries during which the...

at the end of World War I encouraged biological industries to create opportunities for new fermentation products, in particular a market for nonalcoholic drinks. Emil Siebel, the son of the founder of the Zymotechnic Institute, broke away from his father's company to establish his own called the "Bureau of Biotechnology," which specifically offered expertise in fermented nonalcoholic drinks.

The belief that the needs of an industrial society could be met by fermenting agricultural waste was an important ingredient of the "chemurgic movement." Fermentation-based processes generated products of ever-growing utility. In the 1940s, penicillin

Penicillin

Penicillin is a group of antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. They include penicillin G, procaine penicillin, benzathine penicillin, and penicillin V....

was the most dramatic. While it was discovered in England, it was produced industrially in the U.S. using a deep fermentation process originally developed in Peoria, Illinois. The enormous profits and the public expectations penicillin engendered caused a radical shift in the standing of the pharmaceutical industry. Doctors used the phrase "miracle drug", and the historian of its wartime use, David Adams, has suggested that to the public penicillin represented the perfect health that went together with the car and the dream house of wartime American advertising. In the 1950s, steroids were synthesized using fermentation technology. In particular, cortisone

Cortisone

Cortisone is a steroid hormone. It is one of the main hormones released by the adrenal gland in response to stress. In chemical structure, it is a corticosteroid closely related to corticosterone. It is used to treat a variety of ailments and can be administered intravenously, orally,...

promised the same revolutionary ability to change medicine as penicillin had.

Single-cell protein and gasohol projects

Even greater expectations of biotechnology were raised during the 1960s by a process that grew single-cell protein. When the so-called protein gap threatened world hunger, producing food locally by growing it from waste seemed to offer a solution. It was the possibilities of growing microorganisms on oil that captured the imagination of scientists, policy makers, and commerce. Major companies such as British Petroleum (BP) staked their futures on it. In 1962, BP built a pilot plant at Cap de Lavera in Southern France to publicize its product, Toprina. Initial research work at Lavera was done by Alfred Champagnat, In 1963, construction started on BP's second pilot plant at Grangemouth Oil RefineryGrangemouth Refinery

Grangemouth refinery is a mature complex oil refinery located on the Firth of Forth in Grangemouth, Scotland.Currently operated by Ineos, it is Scotland's only oil refinery , and is also the UK's second-oldest; it supplies refined products to customers in Scotland, northern England, Northern...

in Britain.

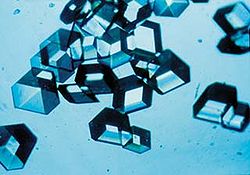

As there was no well-accepted term to describe the new foods, in 1966 the term "single-cell protein" (SCP) was coined at MIT to provide an acceptable and exciting new title, avoiding the unpleasant connotations of microbial or bacterial.

The "food from oil" idea became quite popular by the 1970s, when facilities for growing yeast fed by n-paraffin

Paraffin

In chemistry, paraffin is a term that can be used synonymously with "alkane", indicating hydrocarbons with the general formula CnH2n+2. Paraffin wax refers to a mixture of alkanes that falls within the 20 ≤ n ≤ 40 range; they are found in the solid state at room temperature and begin to enter the...

s were built

in a number of countries. The Soviets

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

were particularly enthusiastic, opening large "BVK" (belkovo-vitaminny kontsentrat, i.e., "protein-vitamin concentrate") plants next to their oil refineries in Kstovo

Kstovo

Kstovo is a town and the administrative center of Kstovsky District of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the right bank of the Volga River, southeast of Nizhny Novgorod. Population: -History:...

(1973) and Kirishi

Kirishi

Kirishi is a town in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, situated on the right bank of the Volkhov River, southeast of St. Petersburg. Population: -History:...

(1974).

By the late 1970s, however, the cultural climate had completely changed, as the growth in SCP interest had taken place against a shifting economic and cultural scene (136). First, the price of oil

Oil

An oil is any substance that is liquid at ambient temperatures and does not mix with water but may mix with other oils and organic solvents. This general definition includes vegetable oils, volatile essential oils, petrochemical oils, and synthetic oils....

rose catastrophically in 1974, so that its cost per barrel was five times greater than it had been two years earlier. Second, despite continuing hunger around the world, anticipated demand also began to shift from humans to animals. The program had begun with the vision of growing food for Third World people, yet the product was instead launched as an animal food for the developed world. The rapidly rising demand for animal feed made that market appear economically more attractive. The ultimate downfall of the SCP project, however, came from public resistance.

This was particularly vocal in Japan, where production came closest to fruition. For all their enthusiasm for innovation and traditional interest in microbiologically produced foods, the Japanese were the first to ban the production of single-cell proteins. The Japanese ultimately were unable to separate the idea of their new "natural" foods from the far from natural connotation of oil. These arguments were made against a background of suspicion of heavy industry in which anxiety over minute traces of petroleum

Petroleum

Petroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

was expressed. Thus, public resistance to an unnatural product led to the end of the SCP project as an attempt to solve world hunger.

Also, in 1989 in the USSR, the public environmental concerns made the government decide to close down (or convert to different technilogies) all 8 paraffin-fed-yeast plants that the Soviet Ministry of Microbiological Industry had by that time.

In the late 1970s, biotechnology offered another possible solution to a societal crisis. The escalation in the price of oil in 1974 increased the cost of the Western world's energy tenfold. In response, the U.S. government promoted the production of gasohol, gasoline with 10 percent alcohol added, as an answer to the energy crisis. In 1979, when the Soviet Union sent troops to Afghanistan, the Carter administration cut off its supplies to agricultural produce in retaliation, creating a surplus of agriculture in the U.S. As a result, fermenting the agricultural surpluses to synthesize fuel seemed to be an economical solution to the shortage of oil threatened by the Iran-Iraq war

Iran-Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between the armed forces of Iraq and Iran, lasting from September 1980 to August 1988, making it the longest conventional war of the twentieth century...

. Before the new direction could be taken, however, the political wind changed again: the Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

administration came to power in January 1981 and, with the declining oil prices of the 1980s, ended support for the gasohol industry before it was born.

Biotechnology seemed to be the solution for major social problems, including world hunger and energy crises. In the 1960s, radical measures would be needed to meet world starvation, and biotechnology seemed to provide an answer. However, the solutions proved to be too expensive and socially unacceptable, and solving world hunger through SCP food was dismissed. In the 1970s, the food crisis was succeeded by the energy crisis, and here too, biotechnology seemed to provide an answer. But once again, costs proved prohibitive as oil prices slumped in the 1980s. Thus, in practice, the implications of biotechnology were not fully realized in these situations. But this would soon change with the rise of genetic engineering

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

.

Genetic engineering

The origins of biotechnology culminated with the birth of genetic engineeringGenetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

. There were two key events that have come to be seen as scientific breakthroughs beginning the era that would unite genetics with biotechnology. One was the 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

, by Watson and Crick, and the other was the 1973 discovery by Cohen and Boyer of a recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

technique by which a section of DNA was cut from the plasmid of an E. coli bacterium and transferred into the DNA of another. This approach could, in principle, enable bacteria to adopt the genes and produce proteins of other organisms, including humans. Popularly referred to as "genetic engineering," it came to be defined as the basis of new biotechnology.

Genetic engineering proved to be a topic that thrust biotechnology into the public scene, and the interaction between scientists, politicians, and the public defined the work that was accomplished in this area. Technical developments during this time were revolutionary and at times frightening. In December 1967, the first heart transplant by Christian Barnard reminded the public that the physical identity of a person was becoming increasingly problematic. While poetic imagination had always seen the heart at the center of the soul, now there was the prospect of individuals being defined by other people's hearts. During the same month, Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg was an American biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 for his discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid " together with Dr. Severo Ochoa of New York University...

announced that he had managed to biochemically replicate a viral gene. "Life had been synthesized," said the head of the National Institutes of Health. Genetic engineering was now on the scientific agenda, as it was becoming possible to identify genetic characteristics with diseases such as beta thalassemia and sickle-cell anemia.

Responses to scientific achievements were colored by cultural skepticism. Scientists and their expertise were looked upon with suspicion. In 1968, an immensely popular work, The Biological Time Bomb, was written by the British journalist Gordon Rattray Taylor. The author's preface saw Kornberg's discovery of replicating a viral gene as a route to lethal doomsday bugs. The publisher's blurb for the book warned that within ten years, "You may marry a semi-artificial man or woman…choose your children's sex…tune out pain…change your memories…and live to be 150 if the scientific revolution doesn’t destroy us first." The book ended with a chapter called "The Future – If Any." While it is rare for current science to be represented in the movies, in this period of "Star Trek

Star Trek

Star Trek is an American science fiction entertainment franchise created by Gene Roddenberry. The core of Star Trek is its six television series: The Original Series, The Animated Series, The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise...

", science fiction and science fact seemed to be converging. "Cloning

Cloning

Cloning in biology is the process of producing similar populations of genetically identical individuals that occurs in nature when organisms such as bacteria, insects or plants reproduce asexually. Cloning in biotechnology refers to processes used to create copies of DNA fragments , cells , or...

" became a popular word in the media. Woody Allen

Woody Allen

Woody Allen is an American screenwriter, director, actor, comedian, jazz musician, author, and playwright. Allen's films draw heavily on literature, sexuality, philosophy, psychology, Jewish identity, and the history of cinema...

satirized the cloning of a person from a nose in his 1973 movie Sleeper

Sleeper (film)

Sleeper is a 1973 futuristic science fiction comedy film, written by Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman, and directed by Allen. The plot involves the adventures of the owner of a Greenwich Village, NY health food store played by Woody Allen who is cryogenically frozen in 1973 and defrosted 200...

, and cloning Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

from surviving cells was the theme of the 1976 novel by Ira Levin

Ira Levin

Ira Levin was an American author, dramatist and songwriter.-Professional life:Levin attended Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa...

, The Boys from Brazil

The Boys from Brazil (novel)

The Boys from Brazil is a 1976 thriller novel by Ira Levin. It was subsequently made into a movie of the same name that was released in 1978.- Plot :...

.

In response to these public concerns, scientists, industry, and governments increasingly linked the power of recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

to the immensely practical functions that biotechnology promised. One of the key scientific figures that attempted to highlight the promising aspects of genetic engineering was Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was just 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and...

, a Stanford professor and Nobel laureate. While in the 1960s "genetic engineering" described eugenics and work involving the manipulation of the human genome

Human genome

The human genome is the genome of Homo sapiens, which is stored on 23 chromosome pairs plus the small mitochondrial DNA. 22 of the 23 chromosomes are autosomal chromosome pairs, while the remaining pair is sex-determining...

, Lederberg stressed research that would involve microbes instead. Lederberg emphasized the importance of focusing on curing living people. Lederberg's 1963 paper, "Biological Future of Man" suggested that, while molecular biology might one day make it possible to change the human genotype, "what we have overlooked is euphenics, the engineering of human development." Lederberg constructed the word "euphenics" to emphasize changing the phenotype

Phenotype

A phenotype is an organism's observable characteristics or traits: such as its morphology, development, biochemical or physiological properties, behavior, and products of behavior...

after conception rather than the genotype

Genotype

The genotype is the genetic makeup of a cell, an organism, or an individual usually with reference to a specific character under consideration...

which would affect future generations.

With the discovery of recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

by Cohen and Boyer in 1973, the idea that genetic engineering would have major human and societal consequences was born. In July 1974, a group of eminent molecular biologists headed by Paul Berg wrote to Science

Science (journal)

Science is the academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and is one of the world's top scientific journals....

suggesting that the consequences of this work were so potentially destructive that there should be a pause until its implications had been thought through. This suggestion was explored at a meeting in February 1975 at California's Monterey Peninsula, forever immortalized by the location, Asilomar

Asilomar

Asilomar can refer to a number of things:* Asilomar State Beach – a beach in California, home to the Asilomar Conference Grounds* Asilomar International Conference on Climate Intervention Technologies in March 2009...

. Its historic outcome was an unprecedented call for a halt in research until it could be regulated in such a way that the public need not be anxious, and it led to a 16-month moratorium until National Institutes of Health

National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health are an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and are the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and health-related research. Its science and engineering counterpart is the National Science Foundation...

(NIH) guidelines were established.

Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was just 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and...

was the leading exception in emphasizing, as he had for years, the potential benefits. At Asilomar

Asilomar

Asilomar can refer to a number of things:* Asilomar State Beach – a beach in California, home to the Asilomar Conference Grounds* Asilomar International Conference on Climate Intervention Technologies in March 2009...

, in an atmosphere favoring control and regulation, he circulated a paper countering the pessimism and fears of misuses with the benefits conferred by successful use. He described "an early chance for a technology of untold importance for diagnostic and therapeutic medicine: the ready production of an unlimited variety of human proteins. Analogous applications may be foreseen in fermentation

Industrial fermentation

Industrial fermentation is the intentional use of fermentation by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi to make products useful to humans. Fermented products have applications as food as well as in general industry.- Food fermentation :...

process for cheaply manufacturing essential nutrients, and in the improvement of microbes for the production of antibiotics and of special industrial chemicals." In June 1976, the 16-month moratorium on research expired with the Director's Advisory Committee (DAC) publication of the NIH guidelines of good practice. They defined the risks of certain kinds of experiments and the appropriate physical conditions for their pursuit, as well as a list of things too dangerous to perform at all. Moreover, modified organisms were not to be tested outside the confines of a laboratory or allowed into the environment.

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

would soon lead to the development of the biotechnology industry. Over the next two years, as public concern over the dangers of recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

research grew, so too did interest in its technical and practical applications. Curing genetic diseases remained in the realms of science fiction, but it appeared that producing human simple proteins could be good business. Insulin

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

, one of the smaller, best characterized and understood proteins, had been used in treating type 1 diabetes for a half century. It had been extracted from animals in a chemically slightly different form from the human product. Yet, if one could produce synthetic human insulin, one could meet an existing demand with a product whose approval would be relatively easy to obtain from regulators. In the period 1975 to 1977, synthetic "human" insulin represented the aspirations for new products that could be made with the new biotechnology. Microbial production of synthetic human insulin was finally announced in September 1978 and was produced by a startup company, Genentech

Genentech

Genentech Inc., or Genetic Engineering Technology, Inc., is a biotechnology corporation, founded in 1976 by venture capitalist Robert A. Swanson and biochemist Dr. Herbert Boyer. Trailing the founding of Cetus by five years, it was an important step in the evolution of the biotechnology industry...

., although that company did not commercialize the product themselves, instead, it licensed the production method to Eli Lilly and Company

Eli Lilly and Company

Eli Lilly and Company is a global pharmaceutical company. Eli Lilly's global headquarters is located in Indianapolis, Indiana, in the United States...

.

The radical shift in the connotation of "genetic engineering" from an emphasis on the inherited characteristics of people to the commercial production of proteins and therapeutic drugs was nurtured by Joshua Lederberg. His broad concerns since the 1960s had been stimulated by enthusiasm for science and its potential medical benefits. Countering calls for strict regulation, he expressed a vision of potential utility. Against a belief that new techniques would entail unmentionable and uncontrollable consequences for humanity and the environment, a growing consensus on the economic value of recombinant DNA emerged.

Biotechnology and industry

With ancestral roots in industrial microbiologyIndustrial microbiology

Industrial microbiology or microbial biotechnology encompasses the use of microorganisms in the manufacture of food or industrial products. The use of microorganisms for the production of food, either human or animal, is often considered a branch of food microbiology...

that date back centuries, the new biotechnology industry grew rapidly beginning in the mid-1970s. Each new scientific advance became a media event designed to capture investment confidence and public support. Although market expectations and social benefits of new products were frequently overstated, many people were prepared to see genetic engineering as the next great advance in technological progress. By the 1980s, biotechnology characterized a nascent real industry, providing titles for emerging trade organizations such as the Industrial Biotechnology Association.

The main focus of attention after insulin were the potential profit makers in the pharmaceutical industry: human growth hormone and what promised to be a miraculous cure for viral diseases, interferon

Interferon

Interferons are proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of pathogens—such as viruses, bacteria, or parasites—or tumor cells. They allow communication between cells to trigger the protective defenses of the immune system that eradicate pathogens or tumors.IFNs belong to...

. Cancer

Cancer

Cancer , known medically as a malignant neoplasm, is a large group of different diseases, all involving unregulated cell growth. In cancer, cells divide and grow uncontrollably, forming malignant tumors, and invade nearby parts of the body. The cancer may also spread to more distant parts of the...

was a central target in the 1970s because increasingly the disease was linked to viruses. By 1980, a new company, Biogen, had produced interferon

Interferon

Interferons are proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of pathogens—such as viruses, bacteria, or parasites—or tumor cells. They allow communication between cells to trigger the protective defenses of the immune system that eradicate pathogens or tumors.IFNs belong to...

through recombinant DNA. The emergence of interferon and the possibility of curing cancer raised money in the community for research and increased the enthusiasm of an otherwise uncertain and tentative society. Moreover, to the 1970s plight of cancer was added AIDS

AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

in the 1980s, offering an enormous potential market for a successful therapy, and more immediately, a market for diagnostic tests based on monoclonal antibodies. By 1988, only five proteins from genetically engineered cells had been approved as drugs by the United States Food and Drug Administration

Food and Drug Administration

The Food and Drug Administration is an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, one of the United States federal executive departments...

(FDA): synthetic insulin

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone central to regulating carbohydrate and fat metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle, and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood, storing it as glycogen in the liver and muscle....

, human growth hormone, hepatitis B vaccine

Hepatitis B vaccine

Hepatitis B vaccine is a vaccine developed for the prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. The vaccine contains one of the viral envelope proteins, hepatitis B surface antigen . It is produced by yeast cells, into which the genetic code for HBsAg has been inserted...

, alpha-interferon, and tissue plasminogen activator

Tissue plasminogen activator

Tissue plasminogen activator is a protein involved in the breakdown of blood clots. It is a serine protease found on endothelial cells, the cells that line the blood vessels. As an enzyme, it catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, the major enzyme responsible for clot breakdown...

(TPa), for lysis of blood clots. By the end of the 1990s, however, 125 more genetically engineered drugs would be approved.

Genetic engineering also reached the agricultural front as well. There was tremendous progress since the market introduction of the genetically engineered Flavr Savr tomato in 1994. Ernst and Young reported that in 1998, 30% of the U.S. soybean crop was expected to be from genetically engineered seeds. In 1998, about 30% of the US cotton and corn crops were also expected to be products of genetic engineering

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

.

Genetic engineering in biotechnology stimulated hopes for both therapeutic proteins, drugs and biological organisms themselves, such as seeds, pesticides, engineered yeasts, and modified human cells for treating genetic diseases. From the perspective of its commercial promoters, scientific breakthroughs, industrial commitment, and official support were finally coming together, and biotechnology became a normal part of business. No longer were the proponents for the economic and technological significance of biotechnology the iconoclasts. Their message had finally become accepted and incorporated into the policies of governments and industry.

Global trends

According to Burrill and Company, an industry investment bank, over $350 billion has been invested in biotech since the emergence of the industry, and global revenues rose from $23 billion in 2000 to more than $50 billion in 2005. The greatest growth has been in Latin AmericaLatin America

Latin America is a region of the Americas where Romance languages – particularly Spanish and Portuguese, and variably French – are primarily spoken. Latin America has an area of approximately 21,069,500 km² , almost 3.9% of the Earth's surface or 14.1% of its land surface area...

but all regions of the world have shown strong growth trends. By 2007 and into 2008, though, a downturn in the fortunes of biotech emerged, at least in the United Kingdom, as the result of declining investment in the face of failure of biotech pipelines to deliver and a consequent downturn in return on investment.

There has been little innovation in the traditional pharmaceutical industry over the past decade and biopharmaceuticals are now achieving the fastest rates of growth against this background, particularly in breast cancer

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer originating from breast tissue, most commonly from the inner lining of milk ducts or the lobules that supply the ducts with milk. Cancers originating from ducts are known as ductal carcinomas; those originating from lobules are known as lobular carcinomas...

treatment. Biopharmaceuticals typically treat sub-sets of the total population with a disease where as traditional drugs are developed to treat the population as a whole. However, one of the great difficulties with traditional drugs are the toxic side effects the incidence of which can be unpredictable in individual patients.

Further reading

- Bud, Robert. "Biotechnology in the Twentieth Century." Social Studies of Science 21.3 (1991), 415-457 .

- Bud, Robert. "History of ‘biotechnology.’" Nature 337 (1989), 10.

- Colwell, Rita R. "Fulfilling the promise of biotechnology." Biotechnology Advances 20 (2002), 215-228.

- Dronamraju, Krishna R. Biological and Social Issues in Biotechnology Sharing. Brookfield: Ashgate Publishing Company, 1998.

- Feldbaum, Carl. "Some History Should Be Repeated." Science 295 (2002), 975.