Insulin

Encyclopedia

Insulin is a hormone

central to regulating carbohydrate

and fat

metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver

, muscle

, and fat tissue to take up glucose

from the blood

, storing it as glycogen

in the liver and muscle.

Insulin stops the use of fat as an energy source by inhibiting the release of glucagon

. With the exception of the metabolic disorder diabetes mellitus

and Metabolic syndrome, insulin is provided within the body in a constant proportion to remove excess glucose from the blood, which otherwise would be toxic. When blood glucose levels fall below a certain level, the body begins to use stored sugar as an energy source through glycogenolysis

, which breaks down the glycogen stored in the liver and muscles into glucose, which can then be utilized as an energy source. As its level is a central metabolic control mechanism, its status is also used as a control signal to other body systems (such as amino acid

uptake by body cells). In addition, it has several other anabolic

effects throughout the body.

When control of insulin levels fails, diabetes mellitus

will result. As a consequence, insulin is used medically to treat some forms of diabetes mellitus. Patients with type 1 diabetes

depend on external insulin (most commonly injected subcutaneously

) for their survival because the hormone is no longer produced internally. Patients with type 2 diabetes

are often insulin resistant

and, because of such resistance, may suffer from a "relative" insulin deficiency. Some patients with type 2 diabetes may eventually require insulin if other medications fail to control blood glucose levels adequately. Over 40% of those with Type 2 diabetes require insulin as part of their diabetes management plan.

Insulin also influences other body functions, such as vascular compliance and cognition

. Once insulin enters the human brain, it enhances learning and memory and benefits verbal memory in particular. Enhancing brain insulin signaling by means of intranasal insulin administration also enhances the acute thermoregulatory and glucoregulatory response to food intake, suggesting that central nervous insulin contributes to the control of whole-body energy homeostasis in humans.

Human insulin is a peptide hormone

composed of 51 amino acid

s and has a molecular weight of 5808 Da. It is produced in the islets of Langerhans

in the pancreas

. The name comes from the Latin

insula for "island". Insulin's structure varies slightly between species

of animals. Insulin from animal sources differs somewhat in "strength" (in carbohydrate metabolism

control effects) in humans because of those variations. Porcine

insulin is especially close to the human

version.

s with changes in the coding region have been identified. A read-through gene

, INS-IGF2, overlaps with this gene at the 5' region and with the IGF2 gene at the 3' region.

s in the promoter region of the human insulin gene bind to transcription factor

s. In general, the A-boxes bind to Pdx1

factors, E-box

es bind to NeuroD

, C-boxes bind to MafA

, and cAMP response elements to CREB

. There are also silencers that inhibit transcription.

residues, and porcine

insulin in one. Even insulin from some species of fish is similar enough to human to be clinically effective in humans. Insulin in some invertebrates is quite similar in sequence to human insulin, and has similar physiological effects. The strong homology seen in the insulin sequence of diverse species suggests that it has been conserved across much of animal evolutionary history. The C-peptide of proinsulin

(discussed later), however, differs much more among species; it is also a hormone, but a secondary one.

The primary structure of bovine insulin was first determined by Frederick Sanger

in 1951.; ; ; After that, this polypeptide was synthesized independently by several groups.

Insulin is produced and stored in the body as a hexamer (a unit of six insulin molecules), while the active form is the monomer. The hexamer is an inactive form with long-term stability, which serves as a way to keep the highly reactive insulin protected, yet readily available. The hexamer-monomer conversion is one of the central aspects of insulin formulations for injection. The hexamer is far more stable than the monomer, which is desirable for practical reasons; however, the monomer is a much faster-reacting drug because diffusion rate is inversely related to particle size. A fast-reacting drug means insulin injections do not have to precede mealtimes by hours, which in turn gives diabetics more flexibility in their daily schedules. Insulin can aggregate and form fibrillar interdigitated beta-sheets. This can cause injection amyloidosis

, and prevents the storage of insulin for long periods.

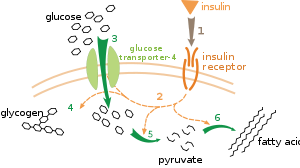

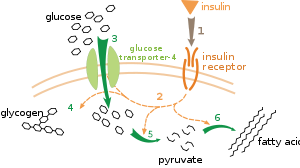

and released when any of several stimuli are detected. These stimuli include ingested protein and glucose in the blood produced from digested food. Carbohydrate

s can be polymers of simple sugars or the simple sugars themselves. If the carbohydrates include glucose, then that glucose will be absorbed into the bloodstream and blood glucose level will begin to rise. In target cells, insulin initiates a signal transduction

, which has the effect of increasing glucose

uptake and storage. Finally, insulin is degraded, terminating the response.

In mammals, insulin is synthesized in the pancreas within the β-cells

In mammals, insulin is synthesized in the pancreas within the β-cells

of the islets of Langerhans

. One million to three million islets of Langerhans (pancreatic islets) form the endocrine part of the pancreas, which is primarily an exocrine gland

. The endocrine portion accounts for only 2% of the total mass of the pancreas. Within the islets of Langerhans, beta cells constitute 65–80% of all the cells.

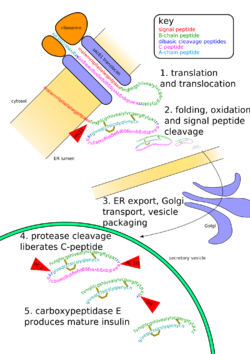

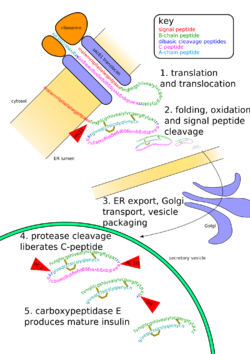

In β-cells, insulin is synthesized from the proinsulin

precursor molecule by the action of proteolytic enzymes, known as prohormone convertases (PC1

and PC2

), as well as the exoprotease carboxypeptidase E

. These modifications of proinsulin remove the center portion of the molecule (i.e., C-peptide

), from the C- and N- terminal ends of proinsulin. The remaining polypeptides (51 amino acids in total), the B- and A- chains, are bound together by disulfide bond

s. However, the primary sequence of proinsulin goes in the order "B-C-A", since B and A chains were identified on the basis of mass, and the C-peptide was discovered after the others.

The endogenous production of insulin is regulated in several steps along the synthesis pathway:

Insulin and its related proteins have been shown to be produced inside the brain, and reduced levels of these proteins are linked to Alzheimer's disease.

release insulin in two phases. The first phase release is rapidly triggered in response to increased blood glucose levels. The second phase is a sustained, slow release of newly formed vesicles triggered independently of sugar. The description of first phase release is as follows:

This is the main mechanism for release of insulin. Also, in general, some release takes place with food intake, not just glucose or carbohydrate

intake, and the β-cells are also somewhat influenced by the autonomic nervous system

. The signaling mechanisms controlling these linkages are not fully understood.

Other substances known to stimulate insulin release include amino acids from ingested proteins, acetylcholine released from vagus nerve endings (parasympathetic nervous system

), gastrointestinal hormones released by enteroendocrine cells of intestinal mucosa and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

(GIP). Three amino acids (alanine, glycine, and arginine) act similarly to glucose by altering the β-cell's membrane potential. Acetylcholine triggers insulin release through phospholipase C, whereas the last acts through the mechanism of adenylate cyclase

.

The sympathetic nervous system

(via α2-adrenergic stimulation as demonstrated by the agonists clonidine

or methyldopa

) inhibit the release of insulin. However, it is worth noting that circulating adrenaline will activate β2-receptors on the β-cells in the pancreatic islets to promote insulin release. This is important, since muscle cannot benefit from the raised blood sugar resulting from adrenergic stimulation (increased gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis from the low blood insulin: glucagon state) unless insulin is present to allow for GLUT-4 translocation in the tissue. Therefore, beginning with direct innervation, norepinephrine

inhibits insulin release via α2-receptors, then subsequently, circulating adrenaline from the adrenal medulla

will stimulate β2-receptors, thereby promoting insulin release.

When the glucose level comes down to the usual physiologic value, insulin release from the β-cells slows or stops. If blood glucose levels drop lower than this, especially to dangerously low levels, release of hyperglycemic hormones (most prominently glucagon

from islet of Langerhans alpha cells) forces release of glucose into the blood from cellular stores, primarily liver cell stores of glycogen. By increasing blood glucose, the hyperglycemic hormones prevent or correct life-threatening hypoglycemia. Release of insulin is strongly inhibited by the stress hormone

norepinephrine

(noradrenaline), which leads to increased blood glucose levels during stress.

Evidence of impaired first-phase insulin release can be seen in the glucose tolerance test

, demonstrated by a substantially elevated blood glucose level at 30 minutes, a marked drop by 60 minutes, and a steady climb back to baseline levels over the following hourly time points.

Even during digestion, in general, one or two hours following a meal, insulin release from the pancreas is not continuous, but oscillates with a period of 3–6 minutes, changing from generating a blood insulin concentration more than about 800 pmol/l to less than 100 pmol/l. This is thought to avoid downregulation of insulin receptor

Even during digestion, in general, one or two hours following a meal, insulin release from the pancreas is not continuous, but oscillates with a period of 3–6 minutes, changing from generating a blood insulin concentration more than about 800 pmol/l to less than 100 pmol/l. This is thought to avoid downregulation of insulin receptor

s in target cells, and to assist the liver in extracting insulin from the blood. This oscillation is important to consider when administering insulin-stimulating medication, since it is the oscillating blood concentration of insulin release, which should, ideally, be achieved, not a constant high concentration. This may be achieved by delivering insulin rhythmically to the portal vein or by islet cell transplantation

to the liver. Future insulin pumps hope to address this characteristic. (See also Pulsatile Insulin

.)

The blood content of insulin can be measured in international unit

The blood content of insulin can be measured in international unit

s, such as µIU/mL or in molar concentration, such as pmol/L, where 1 µIU/mL equals 6.945 pmol/l. A typical blood level between meals is 8–11 μIU/ml (57–79 pmol/l).

s allow glucose from the blood to enter a cell. These transporters are, indirectly, under blood insulin's control in certain body cell types (e.g., muscle cells). Low levels of circulating insulin, or its absence, will prevent glucose from entering those cells (e.g., in type 1 diabetes). More commonly, however, there is a decrease in the sensitivity of cells to insulin (e.g., the reduced insulin sensitivity characteristic of type 2 diabetes), resulting in decreased glucose absorption. In either case, there is 'cell starvation' and weight loss, sometimes extreme. In a few cases, there is a defect in the release of insulin from the pancreas. Either way, the effect is the same: elevated blood glucose levels.

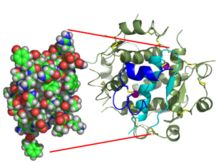

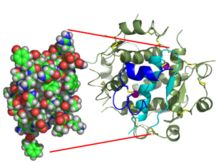

Activation of insulin receptor

s leads to internal cellular mechanisms that directly affect glucose uptake by regulating the number and operation of protein molecules in the cell membrane that transport glucose into the cell. The genes that specify the proteins that make up the insulin receptor in cell membranes have been identified, and the structures of the interior, transmembrane section, and the extra-membrane section of receptor have been solved.

Two types of tissues are most strongly influenced by insulin, as far as the stimulation of glucose uptake is concerned: muscle cells (myocyte

s) and fat cells (adipocyte

s). The former are important because of their central role in movement, breathing, circulation, etc., and the latter because they accumulate excess food energy

against future needs. Together, they account for about two-thirds of all cells in a typical human body.

Insulin binds to the extracellular portion of the alpha subunits of the insulin receptor. This, in turn, causes a conformational change in the insulin receptor that activates the kinase domain residing on the intracellular portion of the beta subunits. The activated kinase domain autophosphorylates tyrosine residues on the C-terminus of the receptor as well as tyrosine residues in the IRS-1 protein.

The actions of insulin on the global human metabolism level include:

The actions of insulin on the global human metabolism level include:

The actions of insulin (indirect and direct) on cells include:

of the insulin-receptor complex, followed by the action of insulin-degrading enzyme. An insulin molecule produced endogenously by the pancreatic beta cells is estimated to be degraded within about one hour after its initial release into circulation (insulin half-life

~ 4–6 minutes).

backbone in triglycerides can also be used to produce blood glucose.

Sufficient lack of glucose and scarcity of these sources of glucose can dramatically make itself manifest in the impaired functioning of the central nervous system

: dizziness, speech problems, and even loss of consciousness. Low glucose is known as hypoglycemia

or, in cases producing unconsciousness, "hypoglycemic coma" (sometimes termed "insulin shock" from the most common causative agent). Endogenous causes of insulin excess (such as an insulinoma

) are very rare, and the overwhelming majority of insulin excess-induced hypoglycemia cases are iatrogenic

and usually accidental. A few cases of murder, attempted murder, or suicide using insulin overdoses have been reported, but most insulin shocks appear to be due to errors in dosage of insulin (e.g., 20 units instead of 2) or other unanticipated factors (did not eat as much as anticipated, or exercised more than expected, or unpredicted kinetics of the subcutaneously injected insulin itself).

Possible causes of hypoglycemia include:

. This technique is anticipated to reduce production costs.

Several of these slightly modified versions of human insulin, while having a clinical effect on blood glucose levels as though they were exact copies, have been designed to have somewhat different absorption or duration of action characteristics. They are usually referred to as "insulin analogues". For instance, the first one available, insulin lispro, does not exhibit a delayed absorption effect found in regular insulin, and begins to have an effect in as little as 15 minutes. Other rapid-acting analogues are NovoRapid and Apidra, with similar profiles. All are rapidly absorbed due to a mutation in the sequence that prevents the insulin analogue from forming dimers and hexamers. Instead, the insulin molecule is a monomer, which is more rapidly absorbed. Using it, therefore, does not require the planning required for other insulins that begin to take effect much later (up to many hours) after administration. Another type is extended-release insulin; the first of these was Lantus (insulin glargine). These have a steady effect for the entire time they are active, without the peak and drop of effect in other insulins; typically, they continue to have an insulin effect for an extended period from 18 to 24 hours. Likewise, another protracted insulin analogue (Levemir) is based on a fatty acid acylation approach. A myristyric acid molecule is attached to this analogue, which in turn associates the insulin molecule to the abundant serum albumin, which in turn extends the effect and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia. Both protracted analogues need to be taken only once-daily, and are very much used in the type 1 diabetes market as the basal insulin. A combination of a rapid acting and a protracted insulin is also available for the patients, making it more likely for them to achieve an insulin profile that mimics that of the body´s own insulin release.

Unlike many medicines, insulin currently cannot be taken orally because, like nearly all other proteins introduced into the gastrointestinal tract

, it is reduced to fragments (even single amino acid components), whereupon all activity is lost. There has been some research into ways to protect insulin from the digestive tract, so that it can be administered orally or sublingually. While experimental, several companies now have various formulations in human clinical trials.

Insulin is usually taken as subcutaneous injection

s by single-use syringe

s with needle

s, via an insulin pump

, or by repeated-use insulin pen

s with needles.

, a medical student in Berlin

, was studying the structure of the pancreas

under a microscope

when he identified some previously unnoticed tissue clumps scattered throughout the bulk of the pancreas. The function of the "little heaps of cells", later known as

the islets of Langerhans

, was unknown, but Edouard Laguesse

later suggested they might produce secretions that play a regulatory role in digestion. Paul Langerhans' son, Archibald, also helped to understand this regulatory role. The term "insulin" origins from insula, the Latin word for islet/island.

In 1889, the Polish-German physician Oscar Minkowski, in collaboration with Joseph von Mering

, removed the pancreas from a healthy dog to test its assumed role in digestion. Several days after the dog's pancreas was removed, Minkowski's animal keeper noticed a swarm of flies feeding on the dog's urine. On testing the urine, they found there was sugar in the dog's urine, establishing for the first time a relationship between the pancreas and diabetes. In 1901, another major step was taken by Eugene Opie, when he clearly established the link between the islets of Langerhans and diabetes: "Diabetes mellitus . . . is caused by destruction of the islets of Langerhans and occurs only when these bodies are in part or wholly destroyed." Before his work, the link between the pancreas and diabetes was clear, but not the specific role of the islets.

Over the next two decades, several attempts were made to isolate whatever it was the islets produced as a potential treatment. In 1906, George Ludwig Zuelzer

Over the next two decades, several attempts were made to isolate whatever it was the islets produced as a potential treatment. In 1906, George Ludwig Zuelzer

was partially successful treating dogs with pancreatic extract, but was unable to continue his work. Between 1911 and 1912, E.L. Scott at the University of Chicago

used aqueous pancreatic extracts, and noted "a slight diminution of glycosuria", but was unable to convince his director of his work's value; it was shut down. Israel Kleiner

demonstrated similar effects at Rockefeller University

in 1915, but his work was interrupted by World War I

, and he did not return to it.

Nicolae Paulescu

, a Romanian

professor of physiology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Bucharest

, was the first to isolate insulin, in 1916, which he called at that time, pancrein, by developing an aqueous pancreatic

extract which, when injected into a diabetic dog, proved to have a normalizing effect on blood sugar

levels. He had to interrupt his experiments because the World War I

and in 1921 he wrote four papers about his work carried out in Bucharest

and his tests on a diabetic dog. Later that year, he detailed his work by publishing an extensive whitepaper on the effect of the pancreatic extract injected into a diabetic animal, which he called: "Research on the Role of the Pancreas

in Food Assimilation" .

Only 8 months later, the discoveries he published were copied (or, as some say, confirmed) by doctor

Frederick Grant Banting

and biochemist

John James Rickard Macleod, who were later awarded the Nobel prize

for the discovery of insulin in 1923, which Paulescu discovered as early as 1916. By the time Banting also isolated insulin, Paulescu already held a patent for his discovery and he was the first to secure the patent rights for his method of manufacturing pancreine/insulin (April 10, 1922, patent no. 6254 (8322) "Pancreina şi procedeul fabricaţiei ei"/"Pancrein and the process of making it", from the Romanian Ministry of Industry

and Trade). Moreover, Banting was very familiar with Paulescu’s work, he even used Paulescu’s “Research on the Role of the Pancreas

in Food Assimilation” as reference in the paper that brought him the Nobel .

State Hospital in Paris

, scheduled for August 27, was cancelled. Also, the French Minister of Health, stated that all his scientific merit must be nullified because of his "brutal inhumanity" of expressing anti-Jewish views. In 2005, the Executive Board of the International Diabetes Federation

decided that "the institute does not be associated with Nicolae Paulescu" because of his anti-semitic views and that "there would be no Paulescu Lecture at World Diabetes Congresses should such a request be received”, all his other lectures, or related to him, were banned.

He was also the first individual to use insulin to reduce blood sugar in a mammal, carrying out a series of treatments on diabetics animals and recording its efficacy when injected.

was reading one of Minkowski's papers and concluded that it was the very digestive secretions that Minkowski had originally studied that were breaking down the islet secretion(s), thereby making it impossible to extract successfully. He jotted a note to himself: "Ligate pancreatic ducts of the dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving islets. Try to isolate internal secretion of these and relieve glycosurea."

The idea was the pancreas's internal secretion, which, it was supposed, regulates sugar in the bloodstream, might hold the key to the treatment of diabetes. A surgeon by training, Banting knew certain arteries could be tied off that would lead to atrophy of most of the pancreas, while leaving the islets of Langerhans intact. He theorized a relatively pure extract could be made from the islets once most of the rest of pancreas was gone.

In the spring of 1921, Banting traveled to Toronto

to explain his idea to J.J.R. Macleod, who was Professor of Physiology at the University of Toronto

, and asked Macleod if he could use his lab space to test the idea. Macleod was initially skeptical, but eventually agreed to let Banting use his lab space while he was on holiday for the summer. He also supplied Banting with ten dogs on which to experiment, and two medical students, Charles Best and Clark Noble, to use as lab assistants, before leaving for Scotland. Since Banting required only one lab assistant, Best and Noble flipped a coin to see which would assist Banting for the first half of the summer. Best won the coin toss, and took the first shift as Banting's assistant. Loss of the coin toss may have proved unfortunate for Noble, given that Banting decided to keep Best for the entire summer, and eventually shared half his Nobel Prize money and a large part of the credit for the discovery of insulin with the winner of the toss. Had Noble won the toss, his career might have taken a different path. Banting's method was to tie a ligature

around the pancreatic duct; when examined several weeks later, the pancreatic digestive cells had died and been absorbed by the immune system, leaving thousands of islets. They then isolated an extract from these islets, producing what they called "isletin" (what we now know as insulin), and tested this extract on the dogs starting July 27. Banting and Best were then able to keep a pancreatectomized dog named Alpha alive for the rest of the summer by injecting her with the crude extract they had prepared. Removal of the pancreas in test animals in essence mimics diabetes, leading to elevated blood glucose levels. Alpha was able to remain alive because the extracts, containing isletin, were able to lower her blood glucose levels.

Banting and Best presented their results to Macleod on his return to Toronto in the fall of 1921, but Macleod pointed out flaws with the experimental design, and suggested the experiments be repeated with more dogs and better equipment. He then supplied Banting and Best with a better laboratory, and began paying Banting a salary from his research grants. Several weeks later, the second round of experiments was also a success; and Macleod helped publish their results privately in Toronto that November. However, they needed six weeks to extract the isletin, which forced considerable delays. Banting suggested they try to use fetal calf pancreas, which had not yet developed digestive glands; he was relieved to find this method worked well. With the supply problem solved, the next major effort was to purify the extract. In December 1921, Macleod invited the biochemist

James Collip

to help with this task, and, within a month, the team felt ready for a clinical test.

On January 11, 1922, Leonard Thompson

, a 14-year-old diabetic who lay dying at the Toronto General Hospital

, was given the first injection of insulin. However, the extract was so impure, Thompson suffered a severe allergic reaction

, and further injections were canceled. Over the next 12 days, Collip worked day and night to improve the ox-pancreas extract, and a second dose was injected on January 23. This was completely successful, not only in having no obvious side-effects but also in completely eliminating the glycosuria sign of diabetes. The first American patient was Elizabeth Hughes Gossett

, the daughter of the governor of New York. The first patient treated in the U.S. was future woodcut artist James D. Havens

; Dr. John Ralston Williams

imported insulin from Toronto to Rochester, New York

, to treat Havens.

Children dying from diabetic ketoacidosis were kept in large wards, often with 50 or more patients in a ward, mostly comatose. Grieving family members were often in attendance, awaiting the (until then, inevitable) death.

In one of medicine's more dramatic moments, Banting, Best, and Collip went from bed to bed, injecting an entire ward with the new purified extract. Before they had reached the last dying child, the first few were awakening from their coma, to the joyous exclamations of their families.

Banting and Best never worked well with Collip, regarding him as something of an interloper, and Collip left the project soon after.

Over the spring of 1922, Best managed to improve his techniques to the point where large quantities of insulin could be extracted on demand, but the preparation remained impure. The drug firm Eli Lilly and Company

had offered assistance not long after the first publications in 1921, and they took Lilly up on the offer in April. In November, Lilly made a major breakthrough and were able to produce large quantities of highly refined insulin. Insulin was offered for sale shortly thereafter.

at the University of Pittsburgh

and Helmut Zahn

at RWTH Aachen

University in the early 1960s.

The first genetically-engineered, synthetic "human" insulin was produced in a laboratory in 1977 by Herbert Boyer

using E. coli

. Partnering with Genentech

founded by Boyer, Eli Lilly and Company

went on in 1982 to sell the first commercially available biosynthetic human insulin under the brand name Humulin

. The vast majority of insulin currently used worldwide is now biosynthetic recombinant "human" insulin or its analogues.

committee in 1923 credited the practical extraction of insulin to a team at the University of Toronto

and awarded the Nobel Prize to two men: Frederick Banting

and J.J.R. Macleod.. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

in 1923 for the discovery of insulin. Banting, insulted that Best was not mentioned, shared his prize with him, and Macleod immediately shared his with James Collip

. The patent for insulin was sold to the University of Toronto

for one half-dollar.

While Paulescu's

pioneering work, which had been cited in Banting and Rickard's prize-winning research, was being completely ignored by the Nobel prize committee, Professor Ian Murray was particularly active in working to correct the historical wrong against Paulescu. Murray was a professor of physiology at the Anderson College of Medicine in Glasgow

, Scotland

, the head of the department of Metabolic Diseases at a leading Glasgow hospital, vice-president of the British Association of Diabetes, and a founding member of the International Diabetes Federation

. In an article for a 1971 issue of the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Murray wrote:

Furthermore, Murray reported:

The primary structure

of insulin was determined by British molecular biologist Frederick Sanger

. It was the first protein to have its sequence be determined. He was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

for this work.

In 1969, after decades of work, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

determined the spatial conformation of the molecule, the so-called tertiary structure

, by means of X-ray diffraction studies. She had been awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964 for the development of crystallography

.

Rosalyn Sussman Yalow

received the 1977 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the development of the radioimmunoassay

for insulin.

Hormone

A hormone is a chemical released by a cell or a gland in one part of the body that sends out messages that affect cells in other parts of the organism. Only a small amount of hormone is required to alter cell metabolism. In essence, it is a chemical messenger that transports a signal from one...

central to regulating carbohydrate

Carbohydrate

A carbohydrate is an organic compound with the empirical formula ; that is, consists only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, with a hydrogen:oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 . However, there are exceptions to this. One common example would be deoxyribose, a component of DNA, which has the empirical...

and fat

Fat

Fats consist of a wide group of compounds that are generally soluble in organic solvents and generally insoluble in water. Chemically, fats are triglycerides, triesters of glycerol and any of several fatty acids. Fats may be either solid or liquid at room temperature, depending on their structure...

metabolism in the body. Insulin causes cells in the liver

Liver

The liver is a vital organ present in vertebrates and some other animals. It has a wide range of functions, including detoxification, protein synthesis, and production of biochemicals necessary for digestion...

, muscle

Muscle

Muscle is a contractile tissue of animals and is derived from the mesodermal layer of embryonic germ cells. Muscle cells contain contractile filaments that move past each other and change the size of the cell. They are classified as skeletal, cardiac, or smooth muscles. Their function is to...

, and fat tissue to take up glucose

Glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

from the blood

Blood

Blood is a specialized bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells....

, storing it as glycogen

Glycogen

Glycogen is a molecule that serves as the secondary long-term energy storage in animal and fungal cells, with the primary energy stores being held in adipose tissue...

in the liver and muscle.

Insulin stops the use of fat as an energy source by inhibiting the release of glucagon

Glucagon

Glucagon, a hormone secreted by the pancreas, raises blood glucose levels. Its effect is opposite that of insulin, which lowers blood glucose levels. The pancreas releases glucagon when blood sugar levels fall too low. Glucagon causes the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose, which is...

. With the exception of the metabolic disorder diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, often simply referred to as diabetes, is a group of metabolic diseases in which a person has high blood sugar, either because the body does not produce enough insulin, or because cells do not respond to the insulin that is produced...

and Metabolic syndrome, insulin is provided within the body in a constant proportion to remove excess glucose from the blood, which otherwise would be toxic. When blood glucose levels fall below a certain level, the body begins to use stored sugar as an energy source through glycogenolysis

Glycogenolysis

Glycogenolysis is the conversion of glycogen polymers to glucose monomers. Glycogen is catabolized by removal of a glucose monomer through cleavage with inorganic phosphate to produce glucose-1-phosphate...

, which breaks down the glycogen stored in the liver and muscles into glucose, which can then be utilized as an energy source. As its level is a central metabolic control mechanism, its status is also used as a control signal to other body systems (such as amino acid

Amino acid

Amino acids are molecules containing an amine group, a carboxylic acid group and a side-chain that varies between different amino acids. The key elements of an amino acid are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen...

uptake by body cells). In addition, it has several other anabolic

Anabolism

Anabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that construct molecules from smaller units. These reactions require energy. One way of categorizing metabolic processes, whether at the cellular, organ or organism level is as 'anabolic' or as 'catabolic', which is the opposite...

effects throughout the body.

When control of insulin levels fails, diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, often simply referred to as diabetes, is a group of metabolic diseases in which a person has high blood sugar, either because the body does not produce enough insulin, or because cells do not respond to the insulin that is produced...

will result. As a consequence, insulin is used medically to treat some forms of diabetes mellitus. Patients with type 1 diabetes

Diabetes mellitus type 1

Diabetes mellitus type 1 is a form of diabetes mellitus that results from autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. The subsequent lack of insulin leads to increased blood and urine glucose...

depend on external insulin (most commonly injected subcutaneously

Subcutaneous injection

A subcutaneous injection is administered as a bolus into the subcutis, the layer of skin directly below the dermis and epidermis, collectively referred to as the...

) for their survival because the hormone is no longer produced internally. Patients with type 2 diabetes

Diabetes mellitus type 2

Diabetes mellitus type 2formerly non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus or adult-onset diabetesis a metabolic disorder that is characterized by high blood glucose in the context of insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency. Diabetes is often initially managed by increasing exercise and...

are often insulin resistant

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is a physiological condition where the natural hormone insulin becomes less effective at lowering blood sugars. The resulting increase in blood glucose may raise levels outside the normal range and cause adverse health effects, depending on dietary conditions. Certain cell types...

and, because of such resistance, may suffer from a "relative" insulin deficiency. Some patients with type 2 diabetes may eventually require insulin if other medications fail to control blood glucose levels adequately. Over 40% of those with Type 2 diabetes require insulin as part of their diabetes management plan.

Insulin also influences other body functions, such as vascular compliance and cognition

Cognition

In science, cognition refers to mental processes. These processes include attention, remembering, producing and understanding language, solving problems, and making decisions. Cognition is studied in various disciplines such as psychology, philosophy, linguistics, and computer science...

. Once insulin enters the human brain, it enhances learning and memory and benefits verbal memory in particular. Enhancing brain insulin signaling by means of intranasal insulin administration also enhances the acute thermoregulatory and glucoregulatory response to food intake, suggesting that central nervous insulin contributes to the control of whole-body energy homeostasis in humans.

Human insulin is a peptide hormone

Peptide hormone

Peptide hormones are a class of peptides that are secreted into the blood stream and have endocrine functions in living animals.Like other proteins, peptide hormones are synthesized in cells from amino acids according to an mRNA template, which is itself synthesized from a DNA template inside the...

composed of 51 amino acid

Amino acid

Amino acids are molecules containing an amine group, a carboxylic acid group and a side-chain that varies between different amino acids. The key elements of an amino acid are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen...

s and has a molecular weight of 5808 Da. It is produced in the islets of Langerhans

Islets of Langerhans

The islets of Langerhans are the regions of the pancreas that contain its endocrine cells. Discovered in 1869 by German pathological anatomist Paul Langerhans at the age of 22, the islets of Langerhans constitute approximately 1 to 2% of the mass of the pancreas...

in the pancreas

Pancreas

The pancreas is a gland organ in the digestive and endocrine system of vertebrates. It is both an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, as well as a digestive organ, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that assist...

. The name comes from the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

insula for "island". Insulin's structure varies slightly between species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of animals. Insulin from animal sources differs somewhat in "strength" (in carbohydrate metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism denotes the various biochemical processes responsible for the formation, breakdown and interconversion of carbohydrates in living organisms....

control effects) in humans because of those variations. Porcine

Pig

A pig is any of the animals in the genus Sus, within the Suidae family of even-toed ungulates. Pigs include the domestic pig, its ancestor the wild boar, and several other wild relatives...

insulin is especially close to the human

Human

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

version.

Alleles

A variety of mutant alleleAllele

An allele is one of two or more forms of a gene or a genetic locus . "Allel" is an abbreviation of allelomorph. Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation...

s with changes in the coding region have been identified. A read-through gene

Conjoined gene

A conjoined gene is defined as a gene, which gives rise to transcripts by combining at least part of one exon from each of two or more distinct known genes which lie on the same chromosome, are in the same orientation, and often translate independently into different proteins...

, INS-IGF2, overlaps with this gene at the 5' region and with the IGF2 gene at the 3' region.

Regulation

Several regulatory sequenceRegulatory sequence

A regulatory sequence is a segment of DNA where regulatory proteins such as transcription factors bind preferentially. These regulatory proteins bind to short stretches of DNA called regulatory regions, which are appropriately positioned in the genome, usually a short distance 'upstream' of the...

s in the promoter region of the human insulin gene bind to transcription factor

Transcription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

s. In general, the A-boxes bind to Pdx1

Pdx1

Pdx1 , also known as insulin promoter factor 1, is a transcription factor necessary for pancreatic development and β-cell maturation...

factors, E-box

E-box

An E-box is a DNA sequence which usually lies upstream of a gene in a promoter region. It is a transcription factor binding site where the specific sequence of DNA, CANNTG, is recognized by proteins that can bind to it to help initiate its transcription. Once transcription factors bind to...

es bind to NeuroD

NeuroD

NeuroD, also called Beta2, is a basic helix loop helix transcription factor expressed in certain parts of brain, beta pancreatic cells and enteroendocrine cells. It is involved in the differentiation of nervous system and development of pancreas...

, C-boxes bind to MafA

Mafa

Mafa is a Local Government Area of Borno State, Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of Mafa.It has an area of 2,869 km² and a population of 103,518 at the 2006 census.The postal code of the area is 611....

, and cAMP response elements to CREB

CREB

CREB is a cellular transcription factor. It binds to certain DNA sequences called cAMP response elements , thereby increasing or decreasing the transcription of the downstream genes....

. There are also silencers that inhibit transcription.

| Regulatory sequence Regulatory sequence A regulatory sequence is a segment of DNA where regulatory proteins such as transcription factors bind preferentially. These regulatory proteins bind to short stretches of DNA called regulatory regions, which are appropriately positioned in the genome, usually a short distance 'upstream' of the... | binding transcription factors |

|---|---|

| ILPR ILPR The insulin-linked polymorphic region is a regulatory sequence on the insulin gene starting at position -363 upstream from the transcriptional start location of the 5' region and consists of multiple repeats of a ACA-GGGGTGGG consensus sequence... |

Par1 DBP (gene) D site of albumin promoter binding protein, also known as DBP, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the DBP gene.... |

| A5 | Pdx1 Pdx1 Pdx1 , also known as insulin promoter factor 1, is a transcription factor necessary for pancreatic development and β-cell maturation... |

| negative regulatory element (NRE) | glucocorticoid receptor Glucocorticoid receptor The glucocorticoid receptor also known as NR3C1 is the receptor to which cortisol and other glucocorticoids bind.... , Oct1 POU2F1 POU domain, class 2, transcription factor 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the POU2F1 gene.-Interactions:POU2F1 has been shown to interact with SNAPC4, Ku80, Glucocorticoid receptor, Sp1 transcription factor, NPAT, POU2AF1, Host cell factor C1, TATA binding protein, RELA, Nuclear... |

| Z (overlapping NRE and C2) | ISF |

| C2 | Pax4 PAX4 Paired box gene 4, also known as PAX4, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the PAX4 gene.- Function :This gene is a member of the paired box family of transcription factors. Members of this gene family typically contain a paired box domain, an octapeptide, and a paired-type homeodomain... , MafA Mafa Mafa is a Local Government Area of Borno State, Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of Mafa.It has an area of 2,869 km² and a population of 103,518 at the 2006 census.The postal code of the area is 611.... (?) |

| E2 | USF1 USF1 Upstream stimulatory factor 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the USF1 gene.-Interactions:USF1 has been shown to interact with USF2, FOSL1 and GTF2I.-External links:... /USF2 USF2 Upstream stimulatory factor 2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the USF2 gene.-Interactions:USF2 has been shown to interact with USF1 , PPRC1 and BRCA1.- Regulation :The USF2 gene is repressed by the microRNA miR-10a.... |

| A3 | Pdx1 Pdx1 Pdx1 , also known as insulin promoter factor 1, is a transcription factor necessary for pancreatic development and β-cell maturation... |

| CREB RE | - |

| CREB RE | CREB CREB CREB is a cellular transcription factor. It binds to certain DNA sequences called cAMP response elements , thereby increasing or decreasing the transcription of the downstream genes.... , CREM |

| A2 | - |

| CAAT enhancer binding (CEB) (partly overlapping A2 and C1) | - |

| C1 | - |

| E1 | E2A, NeuroD1 NEUROD1 Neurogenic differentiation 1 , also called β2 is a transcription factor of the NeuroD-type. It is encoded by the human gene NEUROD1.It is a member of the NeuroD family of basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors... , HEB TCF12 Transcription factor 12 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TCF12 gene.-External links:... |

| A1 | Pdx1 Pdx1 Pdx1 , also known as insulin promoter factor 1, is a transcription factor necessary for pancreatic development and β-cell maturation... |

| G1 | - |

Protein structure

Within vertebrates, the amino acid sequence of insulin is extremely well-preserved. Bovine insulin differs from human in only three amino acidAmino acid

Amino acids are molecules containing an amine group, a carboxylic acid group and a side-chain that varies between different amino acids. The key elements of an amino acid are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen...

residues, and porcine

Pig

A pig is any of the animals in the genus Sus, within the Suidae family of even-toed ungulates. Pigs include the domestic pig, its ancestor the wild boar, and several other wild relatives...

insulin in one. Even insulin from some species of fish is similar enough to human to be clinically effective in humans. Insulin in some invertebrates is quite similar in sequence to human insulin, and has similar physiological effects. The strong homology seen in the insulin sequence of diverse species suggests that it has been conserved across much of animal evolutionary history. The C-peptide of proinsulin

Proinsulin

Proinsulin is the prohormone precursor to insulin made in the beta cells of the islets of Langerhans, specialized regions of the pancreas. In humans, proinsulin is encoded by the INS gene.- Synthesis and post-translational modification :...

(discussed later), however, differs much more among species; it is also a hormone, but a secondary one.

The primary structure of bovine insulin was first determined by Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger, OM, CH, CBE, FRS is an English biochemist and a two-time Nobel laureate in chemistry, the only person to have been so. In 1958 he was awarded a Nobel prize in chemistry "for his work on the structure of proteins, especially that of insulin"...

in 1951.; ; ; After that, this polypeptide was synthesized independently by several groups.

Insulin is produced and stored in the body as a hexamer (a unit of six insulin molecules), while the active form is the monomer. The hexamer is an inactive form with long-term stability, which serves as a way to keep the highly reactive insulin protected, yet readily available. The hexamer-monomer conversion is one of the central aspects of insulin formulations for injection. The hexamer is far more stable than the monomer, which is desirable for practical reasons; however, the monomer is a much faster-reacting drug because diffusion rate is inversely related to particle size. A fast-reacting drug means insulin injections do not have to precede mealtimes by hours, which in turn gives diabetics more flexibility in their daily schedules. Insulin can aggregate and form fibrillar interdigitated beta-sheets. This can cause injection amyloidosis

Amyloidosis

In medicine, amyloidosis refers to a variety of conditions whereby the body produces "bad proteins", denoted as amyloid proteins, which are abnormally deposited in organs and/or tissues and cause harm. A protein is described as being amyloid if, due to an alteration in its secondary structure, it...

, and prevents the storage of insulin for long periods.

Synthesis

Insulin is produced in the pancreasPancreas

The pancreas is a gland organ in the digestive and endocrine system of vertebrates. It is both an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, as well as a digestive organ, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that assist...

and released when any of several stimuli are detected. These stimuli include ingested protein and glucose in the blood produced from digested food. Carbohydrate

Carbohydrate

A carbohydrate is an organic compound with the empirical formula ; that is, consists only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, with a hydrogen:oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 . However, there are exceptions to this. One common example would be deoxyribose, a component of DNA, which has the empirical...

s can be polymers of simple sugars or the simple sugars themselves. If the carbohydrates include glucose, then that glucose will be absorbed into the bloodstream and blood glucose level will begin to rise. In target cells, insulin initiates a signal transduction

Signal transduction

Signal transduction occurs when an extracellular signaling molecule activates a cell surface receptor. In turn, this receptor alters intracellular molecules creating a response...

, which has the effect of increasing glucose

Glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

uptake and storage. Finally, insulin is degraded, terminating the response.

Beta cell

Beta cells are a type of cell in the pancreas located in the so-called islets of Langerhans. They make up 65-80% of the cells in the islets.-Function:...

of the islets of Langerhans

Islets of Langerhans

The islets of Langerhans are the regions of the pancreas that contain its endocrine cells. Discovered in 1869 by German pathological anatomist Paul Langerhans at the age of 22, the islets of Langerhans constitute approximately 1 to 2% of the mass of the pancreas...

. One million to three million islets of Langerhans (pancreatic islets) form the endocrine part of the pancreas, which is primarily an exocrine gland

Gland

A gland is an organ in an animal's body that synthesizes a substance for release of substances such as hormones or breast milk, often into the bloodstream or into cavities inside the body or its outer surface .- Types :...

. The endocrine portion accounts for only 2% of the total mass of the pancreas. Within the islets of Langerhans, beta cells constitute 65–80% of all the cells.

In β-cells, insulin is synthesized from the proinsulin

Proinsulin

Proinsulin is the prohormone precursor to insulin made in the beta cells of the islets of Langerhans, specialized regions of the pancreas. In humans, proinsulin is encoded by the INS gene.- Synthesis and post-translational modification :...

precursor molecule by the action of proteolytic enzymes, known as prohormone convertases (PC1

Proprotein convertase 1

Proprotein convertase 1, also known as prohormone convertase, prohormone convertase 3, or neuroendocrine convertase 1 and often abbreviated as PC1/3 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PCSK1 gene...

and PC2

Proprotein convertase 2

Proprotein convertase 2 also known as prohormone convertase 2 or neuroendocrine convertase 2 is a serine protease and proprotein convertase PC2, like proprotein convertase 1 , is an enzyme responsible for the first step in the maturation of many neuroendocrine peptides from their precursors, such...

), as well as the exoprotease carboxypeptidase E

Carboxypeptidase E

Carboxypeptidase E, also known as carboxypeptidase H and enkephalin convertase, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the CPE gene....

. These modifications of proinsulin remove the center portion of the molecule (i.e., C-peptide

C-peptide

C-peptide is a protein that is produced in the body along with insulin. First preproinsulin is secreted with an A-chain, C-peptide, a B-chain, and a signal sequence. The signal sequence is cut off, leaving proinsulin...

), from the C- and N- terminal ends of proinsulin. The remaining polypeptides (51 amino acids in total), the B- and A- chains, are bound together by disulfide bond

Disulfide bond

In chemistry, a disulfide bond is a covalent bond, usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or disulfide bridge. The overall connectivity is therefore R-S-S-R. The terminology is widely used in biochemistry...

s. However, the primary sequence of proinsulin goes in the order "B-C-A", since B and A chains were identified on the basis of mass, and the C-peptide was discovered after the others.

The endogenous production of insulin is regulated in several steps along the synthesis pathway:

- At transcription from the insulin gene

- In mRNA stability

- At the mRNA translation

- In the posttranslational modificationPosttranslational modificationPosttranslational modification is the chemical modification of a protein after its translation. It is one of the later steps in protein biosynthesis, and thus gene expression, for many proteins....

s

Insulin and its related proteins have been shown to be produced inside the brain, and reduced levels of these proteins are linked to Alzheimer's disease.

Release

Beta cells in the islets of LangerhansIslets of Langerhans

The islets of Langerhans are the regions of the pancreas that contain its endocrine cells. Discovered in 1869 by German pathological anatomist Paul Langerhans at the age of 22, the islets of Langerhans constitute approximately 1 to 2% of the mass of the pancreas...

release insulin in two phases. The first phase release is rapidly triggered in response to increased blood glucose levels. The second phase is a sustained, slow release of newly formed vesicles triggered independently of sugar. The description of first phase release is as follows:

- Glucose enters the β-cells through the glucose transporterGlucose transporterGlucose transporters are a wide group of membrane proteins that facilitate the transport of glucose over a plasma membrane. Because glucose is a vital source of energy for all life these transporters are present in all phyla...

GLUT2GLUT2Glucose transporter 2 also known as solute carrier family 2 , member 2 is a transmembrane carrier protein that enables passive glucose movement across cell membranes. It is the principal transporter for transfer of glucose between liver and blood, and for renal glucose reabsorption... - Glucose goes into glycolysisGlycolysisGlycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+...

and the respiratory cycle, where multiple high-energy ATPAdenosine triphosphateAdenosine-5'-triphosphate is a multifunctional nucleoside triphosphate used in cells as a coenzyme. It is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer. ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism...

molecules are produced by oxidation - Dependent on the ATP:ADP ratio, and hence blood glucose levels, the ATP-dependent potassium channels (K+) close and the cell membrane depolarizes

- On depolarizationDepolarizationIn biology, depolarization is a change in a cell's membrane potential, making it more positive, or less negative. In neurons and some other cells, a large enough depolarization may result in an action potential...

, voltage-controlled calcium channels (Ca2+) open and calcium flows into the cells - An increased calcium level causes activation of phospholipase CPhospholipaseA phospholipase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and other lipophilic substances. There are four major classes, termed A, B, C and D, distinguished by the type of reaction which they catalyze:*Phospholipase A...

, which cleaves the membrane phospholipid phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate into inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerolDiglycerideA diglyceride, or a diacylglycerol , is a glyceride consisting of two fatty acid chains covalently bonded to a glycerol molecule through ester linkages....

. - Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) binds to receptor proteins in the membrane of endoplasmic reticulumEndoplasmic reticulumThe endoplasmic reticulum is an organelle of cells in eukaryotic organisms that forms an interconnected network of tubules, vesicles, and cisternae...

(ER). This allows the release of Ca2+ from the ER via IP3-gated channels, and further raises the cell concentration of calcium. - Significantly increased amounts of calcium in the cells causes release of previously synthesized insulin, which has been stored in secretorySecretionSecretion is the process of elaborating, releasing, and oozing chemicals, or a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast to excretion, the substance may have a certain function, rather than being a waste product...

vesiclesVesicle (biology)A vesicle is a bubble of liquid within another liquid, a supramolecular assembly made up of many different molecules. More technically, a vesicle is a small membrane-enclosed sack that can store or transport substances. Vesicles can form naturally because of the properties of lipid membranes , or...

This is the main mechanism for release of insulin. Also, in general, some release takes place with food intake, not just glucose or carbohydrate

Carbohydrate

A carbohydrate is an organic compound with the empirical formula ; that is, consists only of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, with a hydrogen:oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 . However, there are exceptions to this. One common example would be deoxyribose, a component of DNA, which has the empirical...

intake, and the β-cells are also somewhat influenced by the autonomic nervous system

Autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system is the part of the peripheral nervous system that acts as a control system functioning largely below the level of consciousness, and controls visceral functions. The ANS affects heart rate, digestion, respiration rate, salivation, perspiration, diameter of the pupils,...

. The signaling mechanisms controlling these linkages are not fully understood.

Other substances known to stimulate insulin release include amino acids from ingested proteins, acetylcholine released from vagus nerve endings (parasympathetic nervous system

Parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system is one of the two main divisions of the autonomic nervous system . The ANS is responsible for regulation of internal organs and glands, which occurs unconsciously...

), gastrointestinal hormones released by enteroendocrine cells of intestinal mucosa and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

Gastric inhibitory polypeptide , also known as the glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide is a member of the secretin family of hormones....

(GIP). Three amino acids (alanine, glycine, and arginine) act similarly to glucose by altering the β-cell's membrane potential. Acetylcholine triggers insulin release through phospholipase C, whereas the last acts through the mechanism of adenylate cyclase

Adenylate cyclase

Adenylate cyclase is part of the G protein signalling cascade, which transmits chemical signals from outside the cell across the membrane to the inside of the cell ....

.

The sympathetic nervous system

Sympathetic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system is one of the three parts of the autonomic nervous system, along with the enteric and parasympathetic systems. Its general action is to mobilize the body's nervous system fight-or-flight response...

(via α2-adrenergic stimulation as demonstrated by the agonists clonidine

Clonidine

Clonidine is a sympatholytic medication used to treat medical conditions, such as high blood pressure, some pain conditions, ADHD and anxiety/panic disorder...

or methyldopa

Methyldopa

Methyldopa is an alpha-adrenergic agonist psychoactive drug used as a sympatholytic or antihypertensive. Its use is now mostly deprecated following the introduction of alternative safer classes of agents...

) inhibit the release of insulin. However, it is worth noting that circulating adrenaline will activate β2-receptors on the β-cells in the pancreatic islets to promote insulin release. This is important, since muscle cannot benefit from the raised blood sugar resulting from adrenergic stimulation (increased gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis from the low blood insulin: glucagon state) unless insulin is present to allow for GLUT-4 translocation in the tissue. Therefore, beginning with direct innervation, norepinephrine

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is the US name for noradrenaline , a catecholamine with multiple roles including as a hormone and a neurotransmitter...

inhibits insulin release via α2-receptors, then subsequently, circulating adrenaline from the adrenal medulla

Adrenal medulla

The adrenal medulla is part of the adrenal gland. It is located at the center of the gland, being surrounded by the adrenal cortex. It is the innermost part of the adrenal gland, consisting of cells that secrete epinephrine , norepinephrine , and a small amount of dopamine in response to...

will stimulate β2-receptors, thereby promoting insulin release.

When the glucose level comes down to the usual physiologic value, insulin release from the β-cells slows or stops. If blood glucose levels drop lower than this, especially to dangerously low levels, release of hyperglycemic hormones (most prominently glucagon

Glucagon

Glucagon, a hormone secreted by the pancreas, raises blood glucose levels. Its effect is opposite that of insulin, which lowers blood glucose levels. The pancreas releases glucagon when blood sugar levels fall too low. Glucagon causes the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose, which is...

from islet of Langerhans alpha cells) forces release of glucose into the blood from cellular stores, primarily liver cell stores of glycogen. By increasing blood glucose, the hyperglycemic hormones prevent or correct life-threatening hypoglycemia. Release of insulin is strongly inhibited by the stress hormone

Stress hormone

Stress hormones such as cortisol, GH and norepinephrine are released at periods of high stress. The hormone regulating system is known as the endocrine system...

norepinephrine

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is the US name for noradrenaline , a catecholamine with multiple roles including as a hormone and a neurotransmitter...

(noradrenaline), which leads to increased blood glucose levels during stress.

Evidence of impaired first-phase insulin release can be seen in the glucose tolerance test

Glucose tolerance test

A glucose tolerance test is a medical test in which glucose is given and blood samples taken afterward to determine how quickly it is cleared from the blood. The test is usually used to test for diabetes, insulin resistance, and sometimes reactive hypoglycemia and acromegaly, or rarer disorders of...

, demonstrated by a substantially elevated blood glucose level at 30 minutes, a marked drop by 60 minutes, and a steady climb back to baseline levels over the following hourly time points.

Oscillations

Insulin receptor

In molecular biology, the insulin receptor is a transmembrane receptor that is activated by insulin. It belongs to the large class of tyrosine kinase receptors....

s in target cells, and to assist the liver in extracting insulin from the blood. This oscillation is important to consider when administering insulin-stimulating medication, since it is the oscillating blood concentration of insulin release, which should, ideally, be achieved, not a constant high concentration. This may be achieved by delivering insulin rhythmically to the portal vein or by islet cell transplantation

Islet cell transplantation

Islet transplantation is the transplantation of isolated islets from a donor pancreas and into another person. It is an experimental treatment for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Once transplanted, the islets begin to produce insulin, actively regulating the level of glucose in the blood.Islets are...

to the liver. Future insulin pumps hope to address this characteristic. (See also Pulsatile Insulin

Pulsatile Insulin

Pulsatile insulin, sometimes called metabolic activation therapy, or cellular activation therapy describes in a literal sense the intravenous injection of insulin in pulses versus continuous infusions. Injection of insulin in pulses mimics the physiological secretions of insulin by the pancreas...

.)

Blood content

International unit

In pharmacology, the International Unit is a unit of measurement for the amount of a substance, based on biological activity or effect. It is abbreviated as IU, as UI , or as IE...

s, such as µIU/mL or in molar concentration, such as pmol/L, where 1 µIU/mL equals 6.945 pmol/l. A typical blood level between meals is 8–11 μIU/ml (57–79 pmol/l).

Signal transduction

Special transporter proteins in cell membraneCell membrane

The cell membrane or plasma membrane is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment. The cell membrane is selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules and controls the movement of substances in and out of cells. It basically protects the cell...

s allow glucose from the blood to enter a cell. These transporters are, indirectly, under blood insulin's control in certain body cell types (e.g., muscle cells). Low levels of circulating insulin, or its absence, will prevent glucose from entering those cells (e.g., in type 1 diabetes). More commonly, however, there is a decrease in the sensitivity of cells to insulin (e.g., the reduced insulin sensitivity characteristic of type 2 diabetes), resulting in decreased glucose absorption. In either case, there is 'cell starvation' and weight loss, sometimes extreme. In a few cases, there is a defect in the release of insulin from the pancreas. Either way, the effect is the same: elevated blood glucose levels.

Activation of insulin receptor

Insulin receptor

In molecular biology, the insulin receptor is a transmembrane receptor that is activated by insulin. It belongs to the large class of tyrosine kinase receptors....

s leads to internal cellular mechanisms that directly affect glucose uptake by regulating the number and operation of protein molecules in the cell membrane that transport glucose into the cell. The genes that specify the proteins that make up the insulin receptor in cell membranes have been identified, and the structures of the interior, transmembrane section, and the extra-membrane section of receptor have been solved.

Two types of tissues are most strongly influenced by insulin, as far as the stimulation of glucose uptake is concerned: muscle cells (myocyte

Myocyte

A myocyte is the type of cell found in muscles. They arise from myoblasts.Each myocyte contains myofibrils, which are long, long chains of sarcomeres, the contractile units of the cell....

s) and fat cells (adipocyte

Adipocyte

However, in some reports and textbooks, the number of fat cell increased in childhood and adolescence. The total number is constant in both obese and lean adult...

s). The former are important because of their central role in movement, breathing, circulation, etc., and the latter because they accumulate excess food energy

Food energy

Food energy is the amount of energy obtained from food that is available through cellular respiration.Food energy is expressed in food calories or kilojoules...

against future needs. Together, they account for about two-thirds of all cells in a typical human body.

Insulin binds to the extracellular portion of the alpha subunits of the insulin receptor. This, in turn, causes a conformational change in the insulin receptor that activates the kinase domain residing on the intracellular portion of the beta subunits. The activated kinase domain autophosphorylates tyrosine residues on the C-terminus of the receptor as well as tyrosine residues in the IRS-1 protein.

- phosphorylated IRS-1, in turn, binds to and activates phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3KPhosphoinositide 3-kinasePhosphatidylinositol 3-kinases are a family of enzymes involved in cellular functions such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, motility, survival and intracellular trafficking, which in turn are involved in cancer. In response to lipopolysaccharide, PI3K phosphorylates p65, inducing...

) - PI3K catalyzes the reaction PIP2Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphatePhosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate or PtdInsP2, also known simply as PIP2, is a minor phospholipid component of cell membranes...

+ ATPAdenosine triphosphateAdenosine-5'-triphosphate is a multifunctional nucleoside triphosphate used in cells as a coenzyme. It is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer. ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism...

→ PIP3Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphatePhosphatidylinositol -triphosphate , abbreviated PIP3, is the product of the class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases phosphorylation on phosphatidylinositol -bisphosphate .-Discovery:... - PIP3 activates protein kinase B (PKBAKTAkt, also known as Protein Kinase B , is a serine/threonine protein kinase that plays a key role in multiple cellular processes such as glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, apoptosis, transcription and cell migration.-Family members:...

) - PKB phosphorylates glycogen synthase kinase (GSKGSK-3Glycogen synthase kinase 3 is a serine/threonine protein kinase that mediates the addition of phosphate molecules on certain serine and threonine amino acids in particular cellular substrates...

) and thereby inactivates GSK - GSK can no longer phosphorylate glycogen synthase (GSGlycogen synthaseGlycogen synthase is an enzyme involved in converting glucose to glycogen. It takes short polymers of glucose and converts them into long polymers....

) - unphosphorylated GS makes more glycogenGlycogenGlycogen is a molecule that serves as the secondary long-term energy storage in animal and fungal cells, with the primary energy stores being held in adipose tissue...

- PKB also facilitates vesicle fusion, resulting in an increase in GLUT4 transporters in the plasma membrane

Low-frequency internal motion

According to the study of Raman spectra, a low-frequency wave number of 22 cm−1 has been observed for insulin molecules. Subsequently, it was identified as the accordion-like vibration of the helix (B9-B19) in the B-chain of insulin.Physiological effects

- Control of cellular intake of certain substances, most prominently glucose in muscle and adipose tissue (about two-thirds of body cells)

- Increase of DNA replicationDNA replicationDNA replication is a biological process that occurs in all living organisms and copies their DNA; it is the basis for biological inheritance. The process starts with one double-stranded DNA molecule and produces two identical copies of the molecule...

and protein synthesis via control of amino acid uptake - Modification of the activity of numerous enzymes

The actions of insulin (indirect and direct) on cells include:

- Increased glycogen synthesis – insulin forces storage of glucose in liver (and muscle) cells in the form of glycogen; lowered levels of insulin cause liver cells to convert glycogen to glucose and excrete it into the blood. This is the clinical action of insulin, which is directly useful in reducing high blood glucose levels as in diabetes.

- Increased lipid synthesis – insulin forces fat cells to take in blood lipids, which are converted to triglycerides; lack of insulin causes the reverse.

- Increased esterification of fatty acids – forces adipose tissue to make fats (i.e., triglycerides) from fatty acid esters; lack of insulin causes the reverse.

- Decreased proteolysisProteolysisProteolysis is the directed degradation of proteins by cellular enzymes called proteases or by intramolecular digestion.-Purposes:Proteolysis is used by the cell for several purposes...

– decreasing the breakdown of protein - Decreased lipolysisLipolysisLipolysis is the breakdown of lipids and involves the hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids followed by further degradation into acetyl units by beta oxidation. The process produces Ketones, which are found in large quantities in ketosis, a metabolic state that occurs when the liver...

– forces reduction in conversion of fat cell lipid stores into blood fatty acids; lack of insulin causes the reverse. - Decreased gluconeogenesisGluconeogenesisGluconeogenesis is a metabolic pathway that results in the generation of glucose from non-carbohydrate carbon substrates such as lactate, glycerol, and glucogenic amino acids....

– decreases production of glucose from nonsugar substrates, primarily in the liver (the vast majority of endogenous insulin arriving at the liver never leaves the liver); lack of insulin causes glucose production from assorted substrates in the liver and elsewhere. - Decreased autophagy - decreased level of degradation of damaged organelles. Postprandial levels inhibit autophagy completely.

- Increased amino acid uptake – forces cells to absorb circulating amino acids; lack of insulin inhibits absorption.

- Increased potassium uptake – forces cells to absorb serum potassium; lack of insulin inhibits absorption. Insulin's increase in cellular potassium uptake lowers potassium levels in blood. This possible occurs via insulin-induced translocation of the Na+/K+-ATPaseNa+/K+-ATPaseNa+/K+-ATPase is an enzyme located in the plasma membrane in all animals.- Sodium-potassium pumps :Active transport is responsible for cells containing relatively high...

to the surface of skeletal muscle cells. - Arterial muscle tone – forces arterial wall muscle to relax, increasing blood flow, especially in microarteries; lack of insulin reduces flow by allowing these muscles to contract.

- Increase in the secretion of hydrochloric acid by parietal cells in the stomach

- Decreased renal sodium excretion.

Degradation

Once an insulin molecule has docked onto the receptor and effected its action, it may be released back into the extracellular environment, or it may be degraded by the cell. The two primary sites for insulin clearance are the liver and the kidney. The liver clears most insulin during first-pass transit, whereas the kidney clears most of the insulin in systemic circulation. Degradation normally involves endocytosisEndocytosis

Endocytosis is a process by which cells absorb molecules by engulfing them. It is used by all cells of the body because most substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic plasma or cell membrane...

of the insulin-receptor complex, followed by the action of insulin-degrading enzyme. An insulin molecule produced endogenously by the pancreatic beta cells is estimated to be degraded within about one hour after its initial release into circulation (insulin half-life

Biological half-life

The biological half-life or elimination half-life of a substance is the time it takes for a substance to lose half of its pharmacologic, physiologic, or radiologic activity, as per the MeSH definition...

~ 4–6 minutes).

Hypoglycemia

Although other cells can use other fuels for a while (most prominently fatty acids), neurons depend on glucose as a source of energy in the nonstarving human. They do not require insulin to absorb glucose, unlike muscle and adipose tissue, and they have very small internal stores of glycogen. Glycogen stored in liver cells (unlike glycogen stored in muscle cells) can be converted to glucose, and released into the blood, when glucose from digestion is low or absent, and the glycerolGlycerol

Glycerol is a simple polyol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is widely used in pharmaceutical formulations. Glycerol has three hydroxyl groups that are responsible for its solubility in water and its hygroscopic nature. The glycerol backbone is central to all lipids...