History of Minneapolis, Minnesota

Encyclopedia

Minneapolis, Minnesota

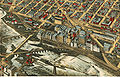

Minneapolis , nicknamed "City of Lakes" and the "Mill City," is the county seat of Hennepin County, the largest city in the U.S. state of Minnesota, and the 48th largest in the United States...

is the largest city

City

A city is a relatively large and permanent settlement. Although there is no agreement on how a city is distinguished from a town within general English language meanings, many cities have a particular administrative, legal, or historical status based on local law.For example, in the U.S...

in the state of Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

in the United States, and the county seat

County seat

A county seat is an administrative center, or seat of government, for a county or civil parish. The term is primarily used in the United States....

of Hennepin County

Hennepin County, Minnesota

Hennepin County is a county located in the U.S. state of Minnesota, named in honor of the 17th-century explorer Father Louis Hennepin. As of 2010 the population was 1,152,425. Its county seat is Minneapolis. It is by far the most populous county in Minnesota; more than one in five Minnesotans live...

. The origin and growth of the city was spurred by the proximity of Fort Snelling, the first major United States military presence in the area, and by its location on Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony, located northeast of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Upper Mississippi River. The natural falls was replaced by a concrete overflow spillway after it partially collapsed in 1869...

, which provided power for sawmill

Sawmill

A sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

s and flour mills

Gristmill

The terms gristmill or grist mill can refer either to a building in which grain is ground into flour, or to the grinding mechanism itself.- Early history :...

.

Fort Snelling was established in 1819, at the confluence of the Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and Minnesota

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of nearly , in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa....

Rivers, and soldiers began using the falls for waterpower. When land became available for settlement, two towns were founded on either side of the falls: Saint Anthony, on the east side, and Minneapolis, on the west side. The two towns later merged into one city in 1872. Early development focused on sawmills, but flour mills eventually became the dominant industry. This industrial development fueled the development of railroads and banks, as well as the foundation of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange

Minneapolis Grain Exchange

The Minneapolis Grain Exchange was formed in 1881 as a regional cash marketplace to promote fair trade and to prevent trade abuses in wheat, oats and corn....

. Through innovations in milling techniques, Minneapolis became a world-leading center of flour production, earning the name "Mill City". As the city grew, the culture developed through its churches, arts institutions, the University of Minnesota

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

, and a famous park system designed by Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth was instrumental in designing the Minneapolis system of parks. Swiss-born, he was widely regarded as the dean of the local parks movement in America. The various titles he was given included administrator of parks, horticulturalist, and park planner. Before emigrating to America...

.

Although the sawmills and the flour

Flour

Flour is a powder which is made by grinding cereal grains, other seeds or roots . It is the main ingredient of bread, which is a staple food for many cultures, making the availability of adequate supplies of flour a major economic and political issue at various times throughout history...

mills are long gone, Minneapolis remains a regional center in banking and industry. The two largest milling companies, General Mills

General Mills

General Mills, Inc. is an American Fortune 500 corporation, primarily concerned with food products, which is headquartered in Golden Valley, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis. The company markets many well-known brands, such as Betty Crocker, Yoplait, Colombo, Totinos, Jeno's, Pillsbury, Green...

and the Pillsbury Company, now merged under the General Mills name, still remain prominent in the Twin Cities area. The city has rediscovered the riverfront, which now hosts parkland, the Mill City Museum

Mill City Museum

Mill City Museum is a Minnesota Historical Society museum in Minneapolis. It opened in 2003, built in the ruins of the Washburn "A" Mill next to Mill Ruins Park on the banks of the Mississippi River...

, and the Guthrie Theater

Guthrie Theater

The Guthrie Theater is a center for theater performance, production, education, and professional training in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is the result of the desire of Sir Tyrone Guthrie, Oliver Rea, and Peter Zeisler to create a resident acting company that would produce and perform the classics in...

.

Early European exploration

Minneapolis grew up around Saint Anthony FallsSaint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony, located northeast of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Upper Mississippi River. The natural falls was replaced by a concrete overflow spillway after it partially collapsed in 1869...

, the only waterfall

Waterfall

A waterfall is a place where flowing water rapidly drops in elevation as it flows over a steep region or a cliff.-Formation:Waterfalls are commonly formed when a river is young. At these times the channel is often narrow and deep. When the river courses over resistant bedrock, erosion happens...

on the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and the end of the commercially navigable section of the river until locks

Lock (water transport)

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber in which the water level can be varied; whereas in a caisson lock, a boat lift, or on a canal inclined plane, it is...

were installed in the 1960s.

Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut

Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut was a French soldier and explorer who is the first European known to have visited the area where the city of Duluth, Minnesota is now located and the headwaters of the Mississippi River near Grand Rapids...

explored the Minnesota area in 1680 on a mission to extend French dominance over the area. While exploring the St. Croix River area, he got word that some other explorers had been held captive. He arranged for their release. The prisoners included Michel Aco

Michel Aco

Michel Aco was a French explorer who, along with René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Father Louis Hennepin, explored the Mississippi River. Aco became La Salle's lieutenant because of his knowledge of Native American languages and his abilities as an explorer...

, Antoine Auguelle

Antoine Auguelle

Antoine Auguelle Picard du Gay was a 17th century French explorer. Born at Amiens in Picardy, Auguelle along with Michel Aco accompanied Father Louis Hennepin during his exploration of the Upper Mississippi River...

, and Father Louis Hennepin

Louis Hennepin

Father Louis Hennepin, O.F.M. baptized Antoine, was a Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Recollect order and an explorer of the interior of North America....

, a Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

priest and missionary

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

. On that expedition, Father Hennepin discovered the falls and named them after his patron saint, Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua or Anthony of Lisbon, O.F.M., was a Portuguese Catholic priest and friar of the Franciscan Order. Though he died in Padua, Italy, he was born to a wealthy family in Lisbon, Portugal, which is where he was raised...

. He published a book in 1683 entitled Description of Louisiana, describing the area to interested Europeans. As time went on, he developed a tendency to exaggerate. A 1699 edition of the book described the falls as having a drop of fifty or sixty feet, when they only had a drop of 16 feet (4.8 m). Hennepin may have been including nearby rapids in his estimate, as the current total drop in river level over the series of dams is 76 ft (23 m).

The city's land was acquired by the United States in a series of treaties and purchases negotiated with the Mdewakanton

Mdewakanton

Mdewakantonwan are one of the sub-tribes of the Isanti Dakota . Their historic home is Mille Lacs Lake in central Minnesota, which in the Dakota language was called mde wakan .As part of the Santee Sioux, their ancestors had migrated from the Southeast of the present-day United States, where the...

band of the Dakota and separately with European nations. England claimed the land east of the Mississippi and France, then Spain, and again France claimed the land west of the river. In 1787 land on the east side of the river became part of the Northwest Territory

Northwest Territory

The Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio...

and in 1803 the west side became part of the Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

, both claimed by the United States. In 1805, Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike Jr. was an American officer and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado is named. As a United States Army captain in 1806-1807, he led the Pike Expedition to explore and document the southern portion of the Louisiana Purchase and to find the headwaters of the Red River,...

purchased two tracts of land from the Dakota Indians. One tract was located at the mouth of the St. Croix River, while a second, larger tract ran from the confluence of the Minnesota

Minnesota River

The Minnesota River is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately 332 miles long, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. It drains a watershed of nearly , in Minnesota and about in South Dakota and Iowa....

and Mississippi Rivers to St. Anthony Falls, with a width of nine miles (14 km) east and west of the river. In return, he distributed about $200 in trading goods and sixty gallons of liquor, and promised a further payment from the United States government. The United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

eventually approved a payment of $2,000.

Fort Snelling and St. Anthony Falls

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

in the winter of 1819–1820. They later moved their camp to Camp Coldwater

Camp Coldwater

Camp Coldwater is an area of several springs that are important to Native Americans, as well as an early European settlement in the state of Minnesota, USA. Camp Coldwater is located adjacent to the Mississippi River in south Minneapolis, directly south of Minnehaha Park.The camp was explored by...

in May 1820. Much of the military's activity was conducted there while the fort was built. Camp Coldwater, the site of a cold, clear, flowing spring, was also considered sacred by the native Dakota.

The soldiers needed to supply the fort, so they built roads and planted vegetables, wheat, and hay, and raised cattle. They also made the first weather recordings in the area. A lumber

Lumber

Lumber or timber is wood in any of its stages from felling through readiness for use as structural material for construction, or wood pulp for paper production....

mill and a grist mill were built on the falls in 1822 to supply the fort.

Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike Jr. was an American officer and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado is named. As a United States Army captain in 1806-1807, he led the Pike Expedition to explore and document the southern portion of the Louisiana Purchase and to find the headwaters of the Red River,...

. His plan was to stake a pre-emption claim at the falls. However, Franklin Steele

Franklin Steele

Franklin Steele was an early and significant settler of Minneapolis, Minnesota in the United States. Born in Chester County, Pennsylvania of Scottish descent, Steele worked in the Lancaster post-office as a young man, where he once met James Buchanan.-Early success:With encouragement from his...

also had plans to stake a claim. On July 15, 1838, word reached Fort Snelling that a treaty between the United States and the Dakota and Ojibwa had been ratified, ceding land between the St. Croix River

St. Croix River (Wisconsin-Minnesota)

The St. Croix River is a tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately long, in the U.S. states of Wisconsin and Minnesota. The lower of the river form the border between Wisconsin and Minnesota. The river is a National Scenic Riverway under the protection of the National Park Service. A...

and the Mississippi Rivers. Steele rushed off to the falls, built a shanty, and marked off boundary lines. Plympton's party arrived the next morning, but they were too late to claim the most desirable land. Plympton claimed some less desirable land near Steele's claim, as did other settlers such as Pierre Bottineau

Pierre Bottineau

Pierre Bottineau was a Minnesota Frontiersman.Known as the "Kit Carson of the Northwest", he was an integral part of the history and development of Minnesota and North Dakota. He was an accomplished surveyor and his many settlement parties founded cities all over Minnesota and North Dakota...

, Joseph Rondo, Samuel Findley, and Baptiste Turpin. Steele went on to build a dam at the falls and built a sawmill that cut logs from the Rum River

Rum River

The Rum River is a slow, meandering channel that connects Minnesota's Mille Lacs Lake with the Mississippi River. It runs for through the farming communities of Onamia, Milaca, Princeton, Cambridge, and Isanti before ending at the Twin Cities suburb of Anoka, roughly 20 miles northwest of downtown...

area.

The Dakota were hunters and gatherers and soon found themselves in debt to fur traders. Pressed by a whooping cough outbreak, loss of buffalo, deer, and bear, and loss of forests to logging, in 1851 in the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux was a treaty signed on July 23, 1851, between the United States government and Sioux Indian bands in Minnesota Territory by which the Sioux ceded territory. The treaty was instigated by Alexander Ramsey, the first governor of Minnesota Territory, and Luke Lea,...

, the Mdewakanton sold the remaining land west of the river, allowing settlement in 1852.

Franklin Steele also had a clever plan to obtain land on the west side of the falls. He suggested to his associated Colonel John H. Stevens

John H. Stevens

John Harrington Stevens was the first authorized resident on the west bank of the Mississippi River in what would become Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was granted permission to occupy the site, then part of the Fort Snelling military reservation, in exchange for providing ferry service to St. Anthony...

that he should bargain with the War Department to obtain some land. Stevens agreed to operate a ferry

Ferry

A ferry is a form of transportation, usually a boat, but sometimes a ship, used to carry primarily passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo as well, across a body of water. Most ferries operate on regular, frequent, return services...

service across the Mississippi in exchange for a claim of 160 acre (0.6474976 km²) just above the government mills. The government approved this bargain, and Stevens built his house in the winter of 1849–1850. The house was the first permanent dwelling on the west bank in the area that became Minneapolis. A few years later, the amount of land controlled by the fort was reduced with an order from U.S. President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore was the 13th President of the United States and the last member of the Whig Party to hold the office of president...

, and rapid settlement followed. The village of Minneapolis soon sprung up on the southwest bank of the river.

St. Anthony

Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island is an island in the Mississippi River just north of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, named for cartographer, Joseph Nicollet. DeLaSalle High School and the Nicollet Island Inn are located there, as well as three multi-family residential buildings and twenty-two restored...

, along with a sawmill equipped with two up-and-down saws. His partner Daniel Stanchfield, a lumberman who had moved to Minnesota, dispatched crews up the Mississippi River to begin cutting lumber. The sawmill began cutting lumber in September 1848. In October 1848, Steele enlisted Ard Godfrey to supervise the mill at a salary of $1500 per year. Steele platted a townsite in 1849 and gave it the name "St. Anthony". The town quickly grew with workers. In addition to the first sawmill and several others that followed, a grist mill was built in 1851. By 1855, the town had approximately 3000 people, and it was incorporated as a city. Godfrey's house, built in 1848, was purchased by the Hennepin County Territorial Pioneers' Association and moved to Chute Square. The house was surveyed in 1934 by the Historic American Buildings Survey

Historic American Buildings Survey

The Historic American Buildings Survey , Historic American Engineering Record , and Historic American Landscapes Survey are programs of the National Park Service established for the purpose of documenting historic places. Records consists of measured drawings, archival photographs, and written...

.

Minneapolis

John H. Stevens

John Harrington Stevens was the first authorized resident on the west bank of the Mississippi River in what would become Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was granted permission to occupy the site, then part of the Fort Snelling military reservation, in exchange for providing ferry service to St. Anthony...

platted a townsite in 1854. He laid out Washington Avenue

Washington Avenue (Minneapolis)

Washington Avenue is a major thoroughfare in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Starting north of Lowry Avenue, the street runs straight south, with Interstate 94 running alongside it until just south of West Broadway, when the freeway turns to the west...

parallel to the river, with other streets running parallel to and perpendicular to Washington. He later questioned his decision, thinking he should have run the streets directly east-west and north-south, but it ended up aligning nicely with the plat of St. Anthony. The wide, straight streets, with Washington and Hennepin Avenue

Hennepin Avenue

Hennepin Avenue is a major street in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. It runs from Lakewood Cemetery , north through the Uptown District of Southwest Minneapolis, through the former "Bottleneck" area west of Loring Park, through the North Loop in the city center, to Northeast Minneapolis and...

being 100 feet (30.5 m) wide and the others being 80 feet (24.4 m) wide, contrasted with Saint Paul

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul is the capital and second-most populous city of the U.S. state of Minnesota. The city lies mostly on the east bank of the Mississippi River in the area surrounding its point of confluence with the Minnesota River, and adjoins Minneapolis, the state's largest city...

's streets that were 60 feet (18.3 m) wide.

Early on the community tried several names, rejecting Albion, All Saints, Lowell, Brooklyn, Addiseville and Winona. The twenty four small lake

Lake

A lake is a body of relatively still fresh or salt water of considerable size, localized in a basin, that is surrounded by land. Lakes are inland and not part of the ocean and therefore are distinct from lagoons, and are larger and deeper than ponds. Lakes can be contrasted with rivers or streams,...

s that are now within the city limits led Charles Hoag

Charles Hoag

Charles Hoag was the city of Minneapolis’s first school master, second Treasurer of Hennepin County and a classical scholar. He is also known to have played a part in the naming of Minneapolis....

, Minneapolis's first school

School

A school is an institution designed for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is commonly compulsory. In these systems, students progress through a series of schools...

master, to suggest Minnehapolis, derived from Minnehaha and mni, the Dakota

Dakota language

Dakota is a Siouan language spoken by the Dakota people of the Sioux tribes. Dakota is closely related to and mutually intelligible with the Lakota language.-Dialects:...

word for water

Water

Water is a chemical substance with the chemical formula H2O. A water molecule contains one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms connected by covalent bonds. Water is a liquid at ambient conditions, but it often co-exists on Earth with its solid state, ice, and gaseous state . Water also exists in a...

, and polis, the Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

word for city.

The Minnesota Territorial Legislature recognized Saint Anthony as a town in 1855 and Minneapolis in 1856. Boundaries were changed and Minneapolis was incorporated as a city in 1867. Minneapolis and Saint Anthony joined in 1872.

Transportation

Hennepin Avenue Bridge

The Hennepin Avenue Bridge is the structure that carries Hennepin County State Aid Highway 52, Hennepin Avenue, across the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota at Nicollet Island. Officially, it is the Father Louis Hennepin Bridge, in honor of the 17th-century explorer Louis Hennepin, who...

, a suspension bridge

Suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck is hung below suspension cables on vertical suspenders. Outside Tibet and Bhutan, where the first examples of this type of bridge were built in the 15th century, this type of bridge dates from the early 19th century...

that was the first bridge built over the full width of the Mississippi River, was built in 1854 and dedicated on January 23, 1855. The bridge had a span of 620 feet (189 m), a roadway of 17 feet (5 m), and was built at a cost of $36,000. The toll was five cents for pedestrians and twenty-five cents for horsedrawn wagons.

The early settlers of Minnesota were anxiously seeking railroad transportation, but insufficient capital was available after the Panic of 1857

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Indeed, because of the interconnectedness of the world economy by the time of the 1850s, the financial crisis which began in the autumn of 1857 was...

. Rails were finally built in Minnesota in 1862, when the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad built its first ten miles (16 km) of track from the Phalen Creek area in St. Paul to a stop just short of St. Anthony Falls. The railroad continued building track from Minneapolis to Elk River

Elk River, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 16,447 people, 5,664 households, and 4,400 families residing in the city. Recent estimates show the population at 21,329 as of 2005. The population density was 385.5 people per square mile . There were 5,782 housing units at an average density of 135.5 per...

in 1864 and to St. Cloud

St. Cloud, Minnesota

St. Cloud is a city in the U.S. state of Minnesota and the largest population center in the state's central region. The population was 65,842 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Stearns County...

in 1866, and from Minneapolis west to Howard Lake

Howard Lake, Minnesota

Howard Lake is a city in Wright County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 1,962 at the 2010 census.-Geography:According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , of which, of it is land and of it is water....

in 1867 and Willmar

Willmar, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 18,351 people, 7,302 households, and 4,461 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,549.9 people per square mile . There were 7,789 housing units at an average density of 657.8 per square mile...

in 1869. Meanwhile, the Minnesota Central, an early predecessor of the Milwaukee Road, built a line from Minneapolis to Fort Snelling in 1865. The railroad gradually extended to Faribault

Faribault, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 20,818 people, 7,472 households, and 4,946 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,644.8 people per square mile . There were 7,668 housing units at an average density of 605.8 per square mile...

, Owatonna

Owatonna, Minnesota

Owatonna is a city in Steele County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 25,599 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Steele County. Owatonna is home to the Steele County Fairgrounds, which hosts the Steele County Free Fair in August....

, and Austin

Austin, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 23,314 people, 9,897 households, and 6,076 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,168.2 people per square mile . There were 10,261 housing units at an average density of 954.3 per square mile...

. It crossed the Iowa border and met up with the McGregor & Western line. This connection gave Minneapolis rail service to Milwaukee

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee is the largest city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin, the 28th most populous city in the United States and 39th most populous region in the United States. It is the county seat of Milwaukee County and is located on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan. According to 2010 census data, the...

via Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin

Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin

Prairie du Chien is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 5,911 at the 2010 census. Its Zip Code is 53821....

, with through service beginning on October 14, 1867.

A streetcar system in the Minneapolis area took shape in 1875, when the Minneapolis Street Railway company began service with horse-drawn cars. Under the leadership of Thomas Lowry

Thomas Lowry

Thomas Lowry was a lawyer, real-estate magnate, and businessman who oversaw much of the early growth the streetcar lines in the Twin Cities area of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and surrounding communities in Minnesota...

, the company merged with the St. Paul Railway Company and took the name Twin City Rapid Transit

Twin City Rapid Transit

The Twin City Rapid Transit Company , also known as Twin City Lines , was a transportation company that operated streetcars, and buses in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area in the U.S. state of Minnesota...

. By 1889, when electrification began, the system had grown to 115 miles (185 km).

Business and industry

The flour milling industry, dating back to the Fort Snelling government mill, later eclipsed the lumber industry in the value of its finished product. Flour production stood at 30000 barrels (4,769.6 m³) in 1860, rising to 256100 barrels (40,716.6 m³) in 1869. Cadwallader C. Washburn

Cadwallader C. Washburn

Cadwallader Colden Washburn was an American businessman, politician, and soldier noted for founding what would later become General Mills and working in government for Wisconsin. He was born in Livermore, Maine, one of seven brothers that included Israel Washburn, Jr., Elihu B. Washburne, William D...

's imposing mill, built in 1866, was six stories high and promoted as the largest mill west of Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

. Other prominent industries at the falls included foundries, machine shops, and textile mills.

During this time, St. Anthony, on the east side, was separate from Minneapolis, on the west side. As a result of inferior management of the water power, St. Anthony found its manufacturing district declining. Some people and organizations started to talk about merging the two cities. A citizens' committee recommended merging the two cities in 1866, but a vote on this issue was rejected in 1867. Minneapolis incorporated as a city in 1867. The two cities found themselves competing with St. Paul, which had a larger population, the head of navigation of the Mississippi River, and more access to railroads.

Threatened collapse of St. Anthony Falls

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed largely of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate . Many limestones are composed from skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera....

overlaying a soft sandstone

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized minerals or rock grains.Most sandstone is composed of quartz and/or feldspar because these are the most common minerals in the Earth's crust. Like sand, sandstone may be any colour, but the most common colours are tan, brown, yellow,...

formation. As the sandstone eroded away, large blocks of limestone would fall off. The expansion of milling and industry at the falls accelerated the process of erosion. If the fragile limestone cap ever eroded away completely, the falls would turn into a rapids that would no longer provide water power. This process came to a head on October 4, 1869, when a tunnel under Hennepin Island and Nicollet Island collapsed and filled with water. With the limestone cap breached, the tunnel quickly created a torrent of water that blasted Hennepin Island and threatened to destroy the falls. The falls were shored up quickly, and over the next several years, the falls were repaired by building a wooden apron, sealing the tunnel, and building low dams above the falls to avoid exposing the limestone to the weather. This work was assisted by the federal government, and was eventually completed in 1884. The federal government spent $615,000 on this effort, while the two cities spent $334,500. Possibly as a result of the bonding needed to rehabilitate the falls, the cities of St. Anthony and Minneapolis merged on April 9, 1872.

Development of flour milling

Millstone

Millstones or mill stones are used in windmills and watermills, including tide mills, for grinding wheat or other grains.The type of stone most suitable for making millstones is a siliceous rock called burrstone , an open-textured, porous but tough, fine-grained sandstone, or a silicified,...

s that would pulverize the grain and grind as much flour as possible in one pass. This system worked best for winter wheat

Winter wheat

Winter wheat is a type of wheat that is planted from September to December in the Northern Hemisphere. Winter wheat sprouts before freezing occurs, then becomes dormant until the soil warms in the spring. Winter wheat needs a few weeks of cold before being able to flower, however persistent snow...

, which was sown in the fall and resumed its growth in the spring. However, the harsh winter conditions of the upper Midwest

Upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the midwest. Although there are no uniformly agreed-upon boundaries, the region is most commonly used to refer to the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and...

did not lend themselves to the production of winter wheat, since the deep frosts and lack of snow cover killed the crop. Spring wheat, which could be sown in the spring and reaped in the summer, was a more dependable crop. However, conventional milling techniques did not produce a desirable product, since the harder husks of spring wheat kernels fractured between the grindstones. The gluten

Gluten

Gluten is a protein composite found in foods processed from wheat and related grain species, including barley and rye...

and starch

Starch

Starch or amylum is a carbohydrate consisting of a large number of glucose units joined together by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by all green plants as an energy store...

in the flour could not be mixed completely, either, and the flour would turn rancid

Rancidification

Rancidification is the chemical decomposition of fats, oils and other lipids . When these processes occur in food, undesirable odors and flavors can result. In some cases, however, the flavors can be desirable . In processed meats, these flavors are collectively known as "warmed over flavor"...

. Minneapolis milling companies solved this problem by inventing the middlings purifier

Middlings purifier

A middlings purifier is a device used in the production of flour to remove the husks from the kernels of wheat.It was developed in Minnesota by Edmund LaCroix, a French inventor hired by Cadwallader C...

, which made it possible to separate the husks from the flour earlier in the milling process. They also developed a gradual-reduction process, where grain was pulverized between a series of rollers made of porcelain, iron, or steel. This process resulted in "patent" flour, which commanded almost double the price of "bakers" or "clear" flour, which it replaced. The Washburn mill attempted to monopolize these techniques, but Pillsbury and other companies lured employees away from Washburn and were able to duplicate the process.

Although the flour industry grew steadily, one major event caused a disturbance in the production of flour. On May 2, 1878, the Washburn "A" Mill exploded when grain dust ignited. The explosion killed eighteen workers and destroyed one-third of the capacity of the milling district

Mills District, Minneapolis

The Mill District is a neighborhood within Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, and a part of the larger Downtown East neighborhood. Its approximate boundaries are the Mississippi River to the north, the I-35W Mississippi River Bridge to the east, Washington Avenue to the south, and 5th Avenue...

, as well as other nearby businesses and residences. By the end of the year, though, seventeen mills were back in operation, including the rebuilt Washburn "A" Mill and others that had been completely rebuilt. The millers also took the opportunity to rebuild with new technology such as dust collection systems. The largest mill on the east side of the river was the Pillsbury "A" Mill, built in 1880–1881 and designed by local architect LeRoy S. Buffington. The Pillsbury Company wanted a building that was beautiful as well as functional. The seven-story building had stone walls six feet thick at the base tapering to eighteen inches at the top. With improvements and additions over the years, it became the world's largest flour mill. The Pillsbury "A" Mill is now a National Historic Landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

, along with the Washburn "A" Mill.

In 1891, Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company

Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company

Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company was an American flour milling company that operated about one quarter of the mills in Minneapolis, Minnesota when the city was the flour milling capital of the world. Formed as a business entity, Northwestern produced flour for the half century between 1891...

was formed, consolidating many of the smaller mills into one corporate entity. Between 1880 and 1930, Minneapolis led the nation in flour production, earning it the nickname "Mill City". Minneapolis surpassed Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

as the world's leading flour miller in 1884, and production stood at about 7000000 barrels (809,397.4 m³) annually in 1890. In 1900, Minneapolis mills were grinding 14.1 percent of the nation's grain, and in 1915–16, flour production hit its peak at 20443000 barrels (2,363,787.3 m³) annually.

Hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity is the term referring to electricity generated by hydropower; the production of electrical power through the use of the gravitational force of falling or flowing water. It is the most widely used form of renewable energy...

power plant in the United States was built at the falls on Upton Island. The Brush Electric Company, headed by Charles F. Brush

Charles F. Brush

Charles Francis Brush was a U.S. inventor, entrepreneur and philanthropist.-Biography:Born in Euclid Township, Ohio, Brush was raised on a farm about 10 miles from downtown Cleveland...

, supplied the equipment, which included five generators. The electricity was transmitted via four circuits to shops on Washington Avenue

Washington Avenue (Minneapolis)

Washington Avenue is a major thoroughfare in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Starting north of Lowry Avenue, the street runs straight south, with Interstate 94 running alongside it until just south of West Broadway, when the freeway turns to the west...

. The power plant turned on the lights on September 5, 1882, just ahead of the Vulcan Street Plant

Vulcan Street Plant

The Vulcan Street Plant is the world's first Edison hydroelectric central station. Built on the Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin, the Vulcan Street Plant was put into operation on September 30, 1882...

in Appleton, Wisconsin

Appleton, Wisconsin

Appleton is a city in Outagamie, Calumet, and Winnebago Counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. It is situated on the Fox River, 30 miles southwest of Green Bay and 100 miles north of Milwaukee. Appleton is the county seat of Outagamie County. The population was 78,086 at the 2010 census...

, which started generating electricity on September 30. The company competed with the Minneapolis Gas Light Company, which later became Minnegasco and is now part of CenterPoint Energy

CenterPoint Energy

CenterPoint Energy is a Fortune 500 electric and natural gas utility serving several markets in the U.S. states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas. It was formerly known as Reliant Energy , NorAm Energy, Houston Industries, and HL&P...

.

In 1895, William de la Barre

William de la Barre

William de la Barre was a Austrian-born civil engineer who developed a new process for milling wheat into flour using energy-saving steel rollers at the Washburn-Crosby Mills in Minneapolis, Minnesota and later served as chief engineer for the first hydroelectric power station built in the...

began building a dam at Meeker Island, 2,200 feet (571 m) downriver from the falls. His objective was to build a hydroelectric plant that would sell energy to Twin City Rapid Transit

Twin City Rapid Transit

The Twin City Rapid Transit Company , also known as Twin City Lines , was a transportation company that operated streetcars, and buses in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area in the U.S. state of Minnesota...

, which was then using steam power to generate electricity. The dam was completed on March 20, 1897. Later, in 1906, he began construction of the Hennepin Island Hydroelectric Plant

Hennepin Island Hydroelectric Plant

The Hennepin Island Hydroelectric Plant also known as the St. Anthony Hydro Plant, sits on the site of early sawmills at St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The current structure was built for electric power in 1882. It is currently operated by Xcel Energy...

. The plant was leased to Minneapolis General Electric, which sublet the plant to Twin City Rapid Transit. Minneapolis General Electric later became Northern States Power Company, which is now known as Xcel Energy

Xcel Energy

Xcel Energy, Inc. is a public utility company based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, serving customers in Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin. Primary services are electricity and natural gas...

.

Railroads

The development of sawmills and flour mills at the falls spurred demand for railroad service to Minneapolis. In 1868, Minneapolis was only served by a spur from St. Paul, from the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific RailroadChicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad

The Milwaukee Road, officially the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad , was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwest and Northwest of the United States from 1847 until its merger into the Soo Line Railroad on January 1, 1986. The company went through several official names...

, and by the fledgling St. Paul and Pacific Railroad. Minneapolis millers found that railroads based in Milwaukee and Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

were favoring their cities by diverting wheat from Minneapolis mills. In response, the owners of several Minneapolis mills chartered the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway

Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway

The Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway was an American Class I railroad that built and operated lines radiating south and west from Minneapolis, Minnesota which existed for 90 years from 1870 to 1960....

, which would connect the Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad

Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad

The Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad is the name for two different railroads in Minnesota.-Historic railroad:The Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad was the first rail link between the Twin Cities and Duluth and came into existence in 1863 when financier Jay Cooke selected Duluth as the...

through Minneapolis to the Iowa border. Meanwhile, Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke was an American financier. Cooke and his firm Jay Cooke & Company were most notable for their role in financing the Union's war effort during the American Civil War...

took control of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in 1871 with the goal of aggregating it into the Northern Pacific Railway

Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a railway that operated in the west along the Canadian border of the United States. Construction began in 1870 and the main line opened all the way from the Great Lakes to the Pacific when former president Ulysses S. Grant drove in the final "golden spike" in...

. Bad economic conditions caused the Panic of 1873

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 triggered a severe international economic depression in both Europe and the United States that lasted until 1879, and even longer in some countries. The depression was known as the Great Depression until the 1930s, but is now known as the Long Depression...

, and the Northern Pacific had to relinquish control of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad and the Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad.

James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill , was a Canadian-American railroad executive. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwest, the northern Great Plains, and Pacific Northwest...

eventually reorganized the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad as the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, which later became the Great Northern Railway. The Manitoba line had two lines leading to the Red River Valley

Red River Valley

The Red River Valley is a region in central North America that is drained by the Red River of the North. It is significant in the geography of North Dakota, Minnesota, and Manitoba for its relatively fertile lands and the population centers of Fargo, Moorhead, Grand Forks, and Winnipeg...

, giving it access to wheat-growing regions, and it served several mills in Minneapolis. The Manitoba's small passenger station at Minneapolis had become inadequate, so Hill decided to build a new depot that he expected to share with other railroads. Since the Manitoba's mainline ran on the east side of the Mississippi, a new bridge across the river was needed to reach the station. The result was the Stone Arch Bridge, completed in 1883. The Minneapolis Union Depot was opened for passenger service on April 25, 1885.

Meanwhile, the Milwaukee Road expanded their presence in Minneapolis with a "Short Line" connection from St. Paul to Minneapolis in 1880 and through the acquisition of the Hastings and Dakota Railroad, which had a line going west from Minneapolis to Montevideo

Montevideo, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 5,346 people, 2,353 households, and 1,444 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,190.5 people per square mile . There were 2,551 housing units at an average density of 568.1 per square mile...

, Ortonville

Ortonville, Minnesota

As of the census of 2000, there were 2,158 people, 923 households, and 594 families residing in the city. The population density was 635.8 people per square mile . There were 1,125 housing units at an average density of 331.4 per square mile...

, and into Aberdeen, South Dakota

Aberdeen, South Dakota

Aberdeen is a city in and the county seat of Brown County, South Dakota, United States, about 125 mi northeast of Pierre. Settled in 1880, it was incorporated in 1882. The city population was 26,091 at the 2010 census. The American News is the local newspaper...

. They also built a large railyard and shops on Hiawatha Avenue just north of Lake Street

Lake Street (Minneapolis)

Lake Street is a major east-west thoroughfare in Minneapolis, Minnesota which is located between 29th and 31st Streets in south Minneapolis. It was named such because it runs through the Chain of Lakes area on the west side of town and passes over a small channel linking Lake Calhoun and Lake of...

, and a large depot on Washington Avenue

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Depot Freight House and Train Shed

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Depot Freight House and Train Shed , now officially named The Depot, is a historic railroad depot in downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Chicago, Milwaukee, St...

.

The Minneapolis, Sault Ste. Marie & Atlantic Railway

Soo Line Railroad

The Soo Line Railroad is the primary United States railroad subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific Railway , controlled through the Soo Line Corporation, and one of seven U.S. Class I railroads. Although it is named for the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste...

got its start in 1883, with a goal of serving Atlantic ports via Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan

Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan

Sault Ste. Marie is a city in and the county seat of Chippewa County in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is in the north-eastern end of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, on the Canadian border, separated from its twin city of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, by the St. Marys River...

and bypassing Chicago altogether.

Other businesses

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

, oats

OATS

OATS - Open Source Assistive Technology Software - is a source code repository or "forge" for assistive technology software. It was launched in 2006 with the goal to provide a one-stop “shop” for end users, clinicians and open-source developers to promote and develop open source assistive...

, and corn

Maize

Maize known in many English-speaking countries as corn or mielie/mealie, is a grain domesticated by indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica in prehistoric times. The leafy stalk produces ears which contain seeds called kernels. Though technically a grain, maize kernels are used in cooking as a vegetable...

, since the usual supply and demand curves were skewed by similar harvest times across the region. In 1883, they introduced its first futures contract

Futures contract

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized contract between two parties to exchange a specified asset of standardized quantity and quality for a price agreed today with delivery occurring at a specified future date, the delivery date. The contracts are traded on a futures exchange...

for hard red spring wheat. In 1947, the organization was renamed the Minneapolis Grain Exchange

Minneapolis Grain Exchange

The Minneapolis Grain Exchange was formed in 1881 as a regional cash marketplace to promote fair trade and to prevent trade abuses in wheat, oats and corn....

, since the term "chamber of commerce

Chamber of commerce

A chamber of commerce is a form of business network, e.g., a local organization of businesses whose goal is to further the interests of businesses. Business owners in towns and cities form these local societies to advocate on behalf of the business community...

" had become synonymous with organizations that lobbied for business and social issues.

The flour milling industry also spurred the growth of banking in the Minneapolis area. Mills required capital for investments in their plants and machinery and for their ongoing operations. By the early 20th century, Minneapolis was known as "the financial center of the Northwest".

Education

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

was founded in 1851, seven years before Minnesota became a state, as a preparatory school. The school was forced to close during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

because of financial difficulties, but with support from John S. Pillsbury

John S. Pillsbury

John Sargent Pillsbury was an American politician, businessman, and philanthropist. A Republican, he served as the eighth Governor of Minnesota from 1876 to 1882.John S. Pillsbury was born in Sutton, New Hampshire...

, it reopened in 1867. William Watts Folwell

William Watts Folwell

William Watts Folwell was the first President of the University of Minnesota.William Watts Folwell attended Hobart College in Geneva, New York, where he received his undergraduate degree in 1857 and his Masters of Arts degree in 1860...

became the first president of the University in 1869. The university granted its first two Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

degrees in 1873, and awarded its first Doctor of Philosophy

Doctor of Philosophy

Doctor of Philosophy, abbreviated as Ph.D., PhD, D.Phil., or DPhil , in English-speaking countries, is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities...

degree in 1888. From its beginnings in the St. Anthony area, the university eventually grew into a large campus on the east bank of the Mississippi, along with its campus in St. Paul and the addition of a West Bank campus in the 1960s.

DeLaSalle High School

DeLaSalle High School (Minneapolis)

DeLaSalle High School is a Catholic, college preparatory high school located for its entire 111-year history on Nicollet Island, adjacent to downtown Minneapolis, USA. Then-Archbishop John Ireland helped raise money to build the new Catholic secondary school in Minneapolis. Only a few months...

was founded by Archbishop John Ireland

John Ireland (archbishop)

John Ireland was the third bishop and first archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota . He became both a religious as well as civic leader in Saint Paul during the turn of the century...

in 1900 as a Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

secondary school. Its early mission was as a commercial school, but in 1920, parents were asking for a college preparatory school. The school has been in operation for over 100 years in several buildings on Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island

Nicollet Island is an island in the Mississippi River just north of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, named for cartographer, Joseph Nicollet. DeLaSalle High School and the Nicollet Island Inn are located there, as well as three multi-family residential buildings and twenty-two restored...

.

Parks

Frederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted was an American journalist, social critic, public administrator, and landscape designer. He is popularly considered to be the father of American landscape architecture, although many scholars have bestowed that title upon Andrew Jackson Downing...

, that would connect parks. Civic leaders also hoped to stimulate economic development and increase land values. Landscape architect Horace Cleveland

Horace Cleveland

Horace William Shaler Cleveland was a noted American landscape architect, sometimes considered second only to Frederick Law Olmsted...

was hired to create a system of parks named the "Grand Rounds".

Lake Harriet was donated to the city by William S. King

William S. King

Colonel William Smith King was a Republican United States Representative for Minnesota from March 4, 1875 to March 3, 1877. He engaged in a variety of other activities, including journalism and surveying. King was born in Malone, New York in Franklin County where he grew up and attended the...

in 1885 and the first bandshell on the lake was built in 1888. The current bandshell, built in 1985, is the fifth one in its location.

Minnehaha Falls

Minnehaha Falls

Minnehaha Creek is a tributary of the Mississippi River located in Hennepin County, Minnesota that extends from Lake Minnetonka in the west and flows east for 22 miles through several suburbs west of Minneapolis and then through south Minneapolis. Including Lake Minnetonka, the watershed for the...

was purchased as a park in 1889. The park was named after a character in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was an American poet and educator whose works include "Paul Revere's Ride", The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline...

's epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha

The Song of Hiawatha

The Song of Hiawatha is an 1855 epic poem, in trochaic tetrameter, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, featuring an Indian hero and loosely based on legends and ethnography of the Ojibwe and other Native American peoples contained in Algic Researches and additional writings of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft...

.

In 1906, Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth was instrumental in designing the Minneapolis system of parks. Swiss-born, he was widely regarded as the dean of the local parks movement in America. The various titles he was given included administrator of parks, horticulturalist, and park planner. Before emigrating to America...

came to Minneapolis as the parks superintendent. During his tenure, the park system increased from 1810 acres (7.3 km²) in 57 properties to 5421 acres (21.9 km²) in 144 properties. The park system, organized around the Minneapolis chain of lakes (including Cedar Lake

Cedar Lake (Minnesota)

Cedar Lake is a lake on the west side of Minneapolis, north of Lake Calhoun and west of Lake of the Isles. The lake is surrounded by parkland on the west side, while the east side borders the Kenwood residential area. The north side is bordered by the Cedar Lake Trail and the BNSF Railway...

, Lake of the Isles

Lake of the Isles

Lake of the Isles is a lake in Minneapolis, Minnesota connected to Cedar Lake and Lake Calhoun. It is home to winter ice skating and hockey, as well as a New Year's Eve celebration featuring roasted marshmallows and hot chocolate...

, Lake Calhoun

Lake Calhoun

Lake Calhoun is the biggest lake in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and part of the city's Chain of Lakes. Surrounded by city park land and circled by bike and walking trails, it is popular for many outdoor activities...

, Lake Harriet, Lake Hiawatha

Lake Hiawatha

Lake Hiawatha is located just north of Lake Nokomis in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was purchased by the Minneapolis park system in 1922 for $550,000. At that time the lake was just a swamp, but over four years, the park system transformed the bog into a beautiful lake surrounded by a...

, and Lake Nokomis

Lake Nokomis

Lake Nokomis is one of several lakes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The lake was originally named Lake Amelia in honor of Captain George Gooding’s daughter, Amelia, in 1819. Its current name was adopted in 1910 to honor Nokomis, grandmother of Hiawatha...

) became a model for park planners around the world. He also encouraged active recreation in the parks, as opposed to just setting aside parks for passive admiration.

Arts

The Minneapolis Institute of ArtsMinneapolis Institute of Arts

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is a fine art museum located in the Whittier neighborhood of Minneapolis, Minnesota, on a campus that covers nearly 8 acres , formerly Morrison Park...

was established in 1883 by twenty-five citizens who were committed to bringing the fine arts into the Minneapolis community. The present building, a neoclassical

Neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture was an architectural style produced by the neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century, manifested both in its details as a reaction against the Rococo style of naturalistic ornament, and in its architectural formulas as an outgrowth of some classicizing...

structure, was designed by the firm of McKim, Mead and White and opened in 1915. It later received additions in 1974 by Kenzo Tange

Kenzo Tange

was a Japanese architect, and winner of the 1987 Pritzker Prize for architecture. He was one of the most significant architects of the 20th century, combining traditional Japanese styles with modernism, and designed major buildings on five continents. Tange was also an influential protagonist of...

and in 2006 by Michael Graves

Michael Graves

Michael Graves is an American architect. Identified as one of The New York Five, Graves has become a household name with his designs for domestic products sold at Target stores in the United States....

.

The Minnesota Orchestra

Minnesota Orchestra

The Minnesota Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.Emil Oberhoffer founded the orchestra as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1903, and it gave its first performance on November 5 of that year. In 1968 the orchestra changed to its name to the Minnesota Orchestra...

dates back to 1903 when it was founded as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. It was renamed the Minnesota Orchestra

Minnesota Orchestra

The Minnesota Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.Emil Oberhoffer founded the orchestra as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1903, and it gave its first performance on November 5 of that year. In 1968 the orchestra changed to its name to the Minnesota Orchestra...

in 1968 and moved into its own building, Orchestra Hall

Orchestra Hall (Minneapolis)

Orchestra Hall, located at Nicollet Mall and 12th Street in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, is home to the Minnesota Orchestra. The Hall was built in 1974 and opened for the 1974 concert season...

, in downtown Minneapolis in 1974.

The Walker Art Center

Walker Art Center

The Walker Art Center is a contemporary art center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. The Walker is considered one of the nation's "big five" museums for modern art along with the Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the Hirshhorn...

was established in 1927 as the first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest. In the 1940s, the museum shifted its focus toward modern art, after a gift from Mrs. Gilbert Walker made it possible to acquire works by Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

, Henry Moore

Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore OM CH FBA was an English sculptor and artist. He was best known for his semi-abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art....

, Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti was a Swiss sculptor, painter, draughtsman, and printmaker.Alberto Giacometti was born in the canton Graubünden's southerly alpine valley Val Bregaglia and came from an artistic background; his father, Giovanni, was a well-known post-Impressionist painter...

, and others. The museum continued its focus on modern art with traveling shows in the 1960s and is now one of the "big five" modern art museums in the U.S.

Churches

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church is a Roman Catholic parish church of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis located in Minneapolis, Minnesota in the United States. It was built on the east bank of the Mississippi River in today's Nicollet Island/East Bank neighborhood; it is the oldest...

was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis in continuous use. The church was originally built by the First Universalist Society, and later became a Catholic church in 1877 when a Catholic French Canadian congregation acquired it.

Longfellow Zoological Gardens

The Longfellow Zoological Gardens was a zoo and garden in Minneapolis's Minnehaha neighborhood in Minnesota, United States.-History:...

. Archbishop John Ireland supervised the planning of the church, originally named the Pro-Cathedral of Minneapolis, along with the Cathedral of St. Paul in Saint Paul. He chose architect Emmanuel Masqueray, who was trained at the École des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts refers to a number of influential art schools in France. The most famous is the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, now located on the left bank in Paris, across the Seine from the Louvre, in the 6th arrondissement. The school has a history spanning more than 350 years,...

in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. The first Mass was held on May 31, 1914. Church leaders desired to build the finest altar in America, handcrafted of the finest marble they could afford. It was elevated to the rank of basilica

Basilica

The Latin word basilica , was originally used to describe a Roman public building, usually located in the forum of a Roman town. Public basilicas began to appear in Hellenistic cities in the 2nd century BC.The term was also applied to buildings used for religious purposes...

and became the first basilica in the United States in 1926. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

as one of the area's finest examples of Beaux-Arts architecture.

Fall of the milling empire

In the first few decades of the 20th century, Minneapolis began to lose its dominant position in the flour milling industry, after reaching its peak in 1915–1916. The rise of steam power, and later electric power, eroded the advantage that St. Anthony Falls provided in water power. The wheat fields of the Dakotas and Minnesota's Red River Valley began suffering from soil exhaustion due to consecutive wheat crops, leading to an increase in wheat leaf rustWheat leaf rust

Wheat leaf rust, is fungal disease that effects wheat, barley and rye stems, leaves and grains. In temperate zones it is destructive on winter wheat because the pathogen overwinters. Infections can lead up to 20% yield loss - exacerbated by dying leaves which fertilize the fungus. The pathogen is...

and related crop diseases. The farmers of the southern plains developed a variety of hardy red winter wheat suitable for bread flour, and the Kansas City area

Kansas City Metropolitan Area

The Kansas City Metropolitan Area is a fifteen-county metropolitan area that is anchored by Kansas City, Missouri and is bisected by the border between the states of Missouri and Kansas. As of the 2010 Census, the metropolitan area has a population of 2,035,334. The metropolitan area is the...

gained prominence in milling. Also, due to changes in rail shipping rates, millers in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

were able to ship their flour more competitively.

Betty Crocker

Betty Crocker AKA: batter witch is a cultural icon, as well as brand name and trademark of American Fortune 500 corporation General Mills. The name was first developed by the Washburn Crosby Company in 1921 as a way to give a personalized response to consumer product questions. The name Betty was...

to answer product questions. They also purchased a radio station in 1924 and renamed it WCCO, standing for "Washburn Crosby Company". Washburn-Crosby merged with several other regional milling companies in 1928 and renamed themselves General Mills

General Mills

General Mills, Inc. is an American Fortune 500 corporation, primarily concerned with food products, which is headquartered in Golden Valley, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis. The company markets many well-known brands, such as Betty Crocker, Yoplait, Colombo, Totinos, Jeno's, Pillsbury, Green...

. Both General Mills and Pillsbury sought to diversify beyond flour milling by sponsoring baking contests and publishing recipes. They also began developing semi-prepared foods, such as Bisquick

Bisquick

Bisquick is a pre-mixed baking product sold by General Mills under their Betty Crocker brand, consisting of flour, shortening, salt, and baking powder ....

and prepared foods, such as Wheaties

Wheaties

Wheaties is a brand of General Mills breakfast cereal. It is well known for featuring prominent athletes on the exterior of the package, and has become a major cultural icon...

.

After 1930, the flour mills gradually began to shut down. The buildings were either vacated or demolished, the railroad trestle that served the mills was demolished, and the former mill canal and mill ruins were filled in with gravel. The last two mills left at the falls were the Washburn "A" Mill and the Pillsbury "A" Mill. In 1965, General Mills shut down the Washburn "A" Mill, along with several other of their oldest mills. All milling operations throughout the city's corridors such as Hiawatha Avenue and the Midtown Greenway ceased by the early 20th century. Demand for rail use also fell as a result.

To continue economic use of the river, civic leaders pushed for plans to build locks and dams, making the Mississippi River navigable above Saint Anthony Falls for the first time. Congressional approval for the Upper Minneapolis Harbor Development Project came in 1937 but it wasn't until 1950 through 1963, that the United States Army Corps of Engineers

United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers is a federal agency and a major Army command made up of some 38,000 civilian and military personnel, making it the world's largest public engineering, design and construction management agency...

constructed two sets of locks

Lock (water transport)

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber in which the water level can be varied; whereas in a caisson lock, a boat lift, or on a canal inclined plane, it is...

at the lower dam and at the falls. They also covered the falls with a permanent concrete apron. The project also resulted in the disfiguration of the Stone Arch Bridge by replacing two of the arches with a steel truss

Truss bridge

A truss bridge is a bridge composed of connected elements which may be stressed from tension, compression, or sometimes both in response to dynamic loads. Truss bridges are one of the oldest types of modern bridges...

.

The rest of Spirit Island was also obliterated in the process.

Politics, corruption, anti-Semitism and social change

Minneapolis was known for anti-SemitismAnti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

beginning in the 1880s and through the 1950s. The city was described as "the capital of anti-Semitism in the United States" in 1946 by Carey McWilliams

Carey McWilliams (journalist)

Carey McWilliams was an American author, editor, and lawyer. He is best known for his writings about social issues in California, including the condition of migrant farm workers and the internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II...

and in 1959 by Gunther Plaut

Gunther Plaut

Wolf Gunther Plaut, CC, O.Ont is a Reform rabbi and author. Plaut was the rabbi of Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto for several decades and since 1978 is its Senior Scholar....

. At that time the city's Jews were excluded from membership in many organizations, faced employment discrimination, and were considered unwelcome residents in some neighborhoods. Jews in Minneapolis were also not allowed to buy homes in certain neighborhoods of Minneapolis

Neighborhoods of Minneapolis

The city of Minneapolis, Minnesota is officially defined by the Minneapolis City Council as divided into eleven communities, each containing multiple official neighborhoods. Informally, there are city areas with colloquial labels...

. In the 1940s a lack of anti-Semitism was noted in the Midwest with the exception of Minneapolis. McWilliams noted in 1946 the lack of anti-Semitism in neighboring Saint Paul

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul is the capital and second-most populous city of the U.S. state of Minnesota. The city lies mostly on the east bank of the Mississippi River in the area surrounding its point of confluence with the Minnesota River, and adjoins Minneapolis, the state's largest city...

.

The 1920s and 1930s of Prohibition

Prohibition

Prohibition of alcohol, often referred to simply as prohibition, is the practice of prohibiting the manufacture, transportation, import, export, sale, and consumption of alcohol and alcoholic beverages. The term can also apply to the periods in the histories of the countries during which the...

, gangsters and mobs ruled the underworld of the city. North Minneapolis was ruled by Jewish gangsters led by Isadore Blumenfield, also known as Kid Cann

Kid Cann

Isadore Blumenfeld , commonly known as Kid Cann, was a Jewish-American organized crime figure based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, for over four decades and remains the most notorious mobster in the history of Minnesota...

, who was also linked to murders, prostitution, money laundering, the destruction of the Minneapolis streetcar system and political bribery. Chief O'Connor of the Saint Paul Police established the O'Connor System which provided a haven for crooks in the capital city and a headache for Minneapolis Police

Minneapolis Police Department

The Minneapolis Police Department is the police department for the city of Minneapolis in the U.S. state of Minnesota. Formed in 1867, it is the second oldest police department in the state of Minnesota, after the Saint Paul Police Department . A short-lived Board of Police Commissioners existed...

. Corruption spread to the MPD as an Irishman named Edward G. "Big Ed" Morgan operated gambling dens with bootleggers

Rum-running

Rum-running, also known as bootlegging, is the illegal business of transporting alcoholic beverages where such transportation is forbidden by law...

under police protection. Danny Hogan

Danny Hogan

"Dapper" Danny Hogan was a charismatic underworld figure and boss of Saint Paul, Minnesota's Irish Mob during Prohibition. Due to his close relationships with the officers of the deeply corrupt St...

, the underworld "Godfather" of Saint Paul allied with Morgan and the two competed with the Jewish gangsters until the wane of Prohibition and Hogan's death.

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Humphrey