History of Shinto Muso-ryu

Encyclopedia

is a traditional school of the Japanese martial art of jōjutsu, the art of handling the Japanese short staff (jō). The art was created with the purpose of defeating a swordsman in combat using the jō, with an emphasis on proper distance, timing and concentration. Additionally, a variety of other weapons are also taught.

The art was founded by the samurai

Musō Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi

(夢想 權之助 勝吉, fl.

c.1605, dates of birth and death unknown) in the early Edo period (1603–1868) and, according to legend, first put to use in a duel

with Miyamoto Musashi

(宮本 武蔵, 1584–1645). The original art created by Musō Gonnosuke has evolved and been added upon ever since its inception and up to modern times. The art was successfully brought outside of its original domain in Fukuoka

and outside of Japan

itself in the 19th and 20th century. The spreading of Shintō Musō-ryū beyond Japan was largely the effort of Takaji Shimizu (Shimizu Takaji, 1896–1978), considered the 25th headmaster. With the assistance of his own students and the cooperation of the kendo

community, Shimizu spread Shintō Musō-ryū worldwide.

Japan's Warring States period

Japan's Warring States period

(1467–1615), which had scarred Japan for almost 150 years, came to an end with the establishment of the authoritarian Tokugawa shogunate

. This in turn ushered in an era of peace that would last for over 260 years and ended with the overthrow of the shogunate in 1868. The relatively peaceful Edo period

took away the means of the samurai

to fully develop and test their skills in actual battlefield combat. The role of the samurai would eventually change from being warriors, constantly fighting battles for their liege lord (daimyo

), into the role of providing internal security with increasingly more bureaucratic duties. Instead of fighting the frequent wars

and battles of the old days, with the exception of the siege of Osaka

in 1615 and the Shimabara Rebellion

in 1637, many samurai resorted to duelling other samurai with others going on the road as a wandering swordsman to test their skills against other swordsmen such as bandits and ronin

, and some would train in far away schools (ryū

) to hone their skill.

One of the men who went on a warrior's pilgrimage (musha shugyo

One of the men who went on a warrior's pilgrimage (musha shugyo

) was Musō Gonnosuke, a samurai with considerable martial arts experience. Gonnosuke used his training in the arts of the sword (kenjutsu

), glaive

(naginatajutsu

), spear (sōjutsu

), and staff (bōjutsu

), which he acquired from his studies in Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū

, to develop a new way of handling the jō in combat.

Gonnosuke was said to have fully mastered the secret form called The Sword of One Cut (Ichi no Tachi), a form that were developed by the founder of the Kashima Shinto-ryū

and later spread to other Kashima schools such as Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū and Kashima Shin-ryū. His experiences, which would climax in his duels with the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, was the main event which led him create a set of techniques for the jō and establish a new school which he named Shintō Musō-ryū. The techniques were intended to be used against an opponent armed with either one or two swords. Among the advantages of the jō is its superior length when matched against a sword. The extra length enables the wielder to keep the swordman at a disadvantage and this is frequently applied in SMR.

The legend states that Musō Gonnosuke fought two duels with Miyamoto Musashi and was defeated in the first but victorious in the second, using his newly developed jōjutsu techniques to either defeat Musashi or force the duel into a draw. The first duel is described in the annals known as Niten Ki, which is a list of anecdotes told about Musashi and compiled by Musashi's followers after his death. The Niten Ki describes the first duel to have taken place c.1610. One of several legends states that after his defeat he withdrew to the Homan-zan mountain in the northern part of Kyushu and spent his days meditating, training and underwent austere religious rituals. While resting near a fire in a certain temple, Gonnosuke heard a voice say "Be mindful of the strategy 'the moon reflected in the water' (suigetsu)". The tradition states that was his inspiration to develop his new techniques and go fight Musashi a second time.

After the creation of his jō techniques and his establishment as a skilled jōjutsu practitioner he was invited by the Kuroda

clan

of northern Kyūshū

(in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture

) to teach his jōjutsu to their warriors. Gonnosuke accepted the invitation and settled there.

school of swordsmanship (battōjutsu

) , used swords which were longer than the length legally permitted by the Tokugawa Shogunate

. As a result, Kage-ryū went "underground" , but was kept active in strict secrecy until the Meiji Restoration

hundreds of years later.

The main students of Gonnosuke's jōjutsu were the men charged with policing the Kuroda clan's domain (Kuroda-han). Several other schools (ryū

) were created and taught in the Kuroda-han and in the various branches of the Shintō Musō-ryū system. During this period, two newly created schools which included the art of the police truncheon

(jūtte), (among other weapons), and the art of restraining a man with rope (hojōjutsu

), was taught within the branches of the Shintō Musō-ryū as a complement to the arresting (torite)-arts.

After Gonnosukes death the art was mainly transmitted by the "Dangyō-shiyaku" (men's arts instructor), though not all branches of the Kuroda staff-traditions used the title of Dangyō-shiyaku. The Dangyō-instructor position was, unlike the swordsmanship instructor (kagyō) a non-hereditary position within the hierarchy of the Samurai.

The Dangyō-instructor in the Kuroda-domain was the charged with teaching the lower ranking warriors (ashigaru) in the arts of the staff (jō), capturing/seizing/escaping (torite), gunnery (hōjutsu) and rope

(nawa) among other arts. The position of Dangyō-instructor lasted until the abolishment of the Samurai and the feudal system in the 1860-70's.

Over time there would arise seven different lineages from the main Shintō Musō-ryū system. These are collectively known as "The Staff of Kuroda" (Kuroda no jō). Of these seven branches and styles of Gonnosuke's jōjutsu, only two would survive the ending of Japan's feudal system in 1867 and the resulting socio-economic modernization, to be merged into a single line that is today the modern .

The first split in the SMR occurred after the death of the fourth headmaster (師範家 Headmaster) Higuchi Han'emon. The split was the result of one of his licensed (menkyo kaiden) students, Harada Heizo Nobusada, breaking away to establish the (later informally known as Kansai-ryū), while another licensed student Higuchi Han'emon continued the original "True Path" line (later known as Moroki-ryū).

For several years Gonnosukes art was passed on by these two lines. The "New Just" line continued until after the death of its headmaster Nagatomi Koshiro Hisatomo in 1772. Afterwards, the "New Just" line branched off into two separate traditions. The primary reason for this branching, though indirectly, was the result of a restructuring of the living and training quarters of the warriors at the Chikuzen

castle. The low-ranking foot soldiers (ashigaru

) and the junior officers (kashi) were relocated to two separate areas of Fukuoka, partially due to the difference in the social status of the two groups. Each group would create new centres of training in their respective areas. This led to the establishment of two new branches from the "New Just"-line of Jōjutsu, each under their own respective head instructor. These were named haruyoshi, led by Ono Kyusaku, and the other jigyo, led by Komori Seibei. The two branches were named after the two respective areas of the castle in which they trained.

These new branches, jigyo and haruyoshi, were a reality by the early 19th century, but even though separate, all three lines appear to have been very similar in terms of techniques. This was demonstrated when the jigyo Branch was broken with the death of its head instructor Fujimoto Heikichi in 1815. The jigyo found itself without a student with the full transmission of the tradition and without a successor from within its own organisation the line would have died out. However, Hatae Kyuhei, who held a full license in the haruyoshi branch, would eventually revive the jigyo branch and allow it to continue into the Meiji Period

(1868–1912).

Meanwhile, the "True Path" had also fallen onto hard times as the tradition was broken with the death of Inoue Ryosuke in 1831. The similarities between the various "Staff of Kuroda"-traditions were again made clear when Hatae Kyuhei (who was an exponent of the haruyoshi-branch and had also helped revive the jigyo branch of the "New Just line") revived the "True Path". The "True Path" would, however, become extinct in the Bakumatsu era (1850–1867).

It was not until 1871 that the ban on teaching outside the Kuroda clan was lifted.

With the abolishment of the shogunate in 1868

With the abolishment of the shogunate in 1868

and easing of bureaucratic restrictions

, it meant that now Shintō Musō-ryū (and many more martial arts) was allowed to be taught outside the traditional family lands.

It also meant that the numerous benefits of the traditional clan

system was abolished along with it, and the numerous menkyo holders of SMR, who had lived, worked and trained with the financial support of the Daimyo

(aristocratic landowners), would scatter and had to make a new living for themselves. The abolishment of the warrior-caste and the feudal-system led to a rapid modernisation of Japan. During this era many of the old bushi (warriors of all ranks) abandoned martial arts training altogether as it represented an era that was now gone. Throughout Japan most of the surviving traditions were kept alive, if only barely, by the former samurai and other individuals, who now had to find a new place in the new Japan which frowned upon the old martial way. Some of the old ryu were better off than others in the transition by not being overly dependent on government sponsorship.

During this transition-period and beyond various groups of former Kuroda bushi held sporadic meetings and training sessions in memory of the now bygone era. The old bushi present at these sessions included Uchida Ryogoro, Shiraishi Hanjiro and many of the former Dangyo (instructors) of the Kuroda clan. Due to newfound cooperation between the surviving SMR-lineages there were several joint-licenses of the Haruyoshi and Jigyo-branches of SMR issued with Shiraishi Hanjiro Shigeaki receiving a full Menkyo Kaiden license in the late 19th century. By the end of the Meiji era, (1912), only Shiraishi was still active as a fully qualified exponent and dedicated teacher of the last two remaining Kuroda Jō lineages. Shiraishi's dojo was located in Hakata

, a city that was merged with Fukuoka. Shiraishi would teach Shintō Musō-ryū in there until his death in 1927.

Shiraishis senior, Uchida Ryogoro

, decided to travel to Tokyo and teach and expand the art there while Shiraishi stayed in the designated Shintō Musō-ryū headquarters in Fukuoka.

Shiraishi Hanjiro was born in 1842 and was a lower class bushi. As a bushi he learned jojutsu, kenjutsu and other warrior-arts as was expected of a samurai. After the fall of the samurai government, Shiraishi did his best to sustain the jojutsu tradition he had learned. He helped organise the post-samurai meetings and training-sessions of old Kuroda-warriors and would receive his full license in SMR-jojutsu during one of these sessions. Shiraishi eventually opened up a dojo in Fukuoka City and taught the art there. Sometime in the late 19th century, Shiraishi started learning the art of Kusarigama (chain and sickle weapon) as taught by the Isshin-ryū tradition. He would eventually receive a Menkyo Kaiden in this system and started teaching kusarigamajutsu alongside jojutsu in his Fukuoka dojo. Shiraishi would award Menkyo Kaiden to several of his jojutsu students who carried on the tradition as a side-art to SMR-jojutsu.

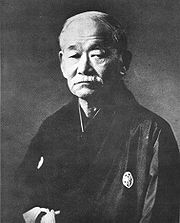

In the early 20th century Uchida Ryogoro arrived in Tokyo and set up shop, teaching jōjutsu to high-rankers in the Japanese society at the time. His students included Nakayama Hakudo

(1873–1958), founder of Muso Shinden-ryū

and Komita Takayoshi, founder of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai

("Great Japan Budō Preservation Society"). It was during this time that Jigoro Kano were first invited to Fukuoka to observe SMR which would herald the cooperation between the two arts in Tokyo. Uchida Ryogoro also taught at the Naval Officers Club and later at the Shiba Kōen park. Ryogoro's son, Uchida Ryōhei, joined him in Tokyo and studied under his father there and was instrumental in developing his father's Tanjōjutsu art

into a working set of techniques. Uchida Ryogoro died in 1921. Uchidas efforts in Tokyo greatly assisted in establishing a connection with the various martial arts communities already based in Tokyo and would help pave the way Shimizu Takajis own efforts at popularizing SMR and establishing a new SMR presence.

Shimizu Takaji was born in 1897 and came from humble origins, his family descending from a line of village headmen and minor officials. In the aftermath of the abolishment of the samurai caste, Shimizu's father would manage a small general store while Shimizu, after graduating from elementary school, took employment in a small factory at Hakata

Shimizu Takaji was born in 1897 and came from humble origins, his family descending from a line of village headmen and minor officials. In the aftermath of the abolishment of the samurai caste, Shimizu's father would manage a small general store while Shimizu, after graduating from elementary school, took employment in a small factory at Hakata

, where the Shiraishi Dojo operated. Shimizu started his training at the age of 17 under Shiraishi and quickly rose in the ranks, receiving the mokuroku scroll in 1918 and the license of full transmission (Menkyo kaiden) in 1920 at the age of 23. Of the many students of Shiraishi there were three who became prominent in the aftermath of Shiraishi's death. Shimizu Takaji, Takayama Kiroku and Otofuji Ichizo.

In 1929 Takayama Kiroku with financial aid from Shiraishis family opened a dojo in Fukuoka and was named Shihan with Shimizu named fuku-shihan or "assistant master". Shimizu by this time, however, was on his way to Tokyo in order to teach Jōdo. Takayama died within a few years after the opening of the Fukuoka dojo and Otofuji Ichizo took over as the new master of the dojo and of the Fukuoka-jō, a responsibility he held until his death in 1998.

In the early 1920s Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo

In the early 1920s Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo

, witnessed a demonstration of SMR and made an invitation to Shiraishi come to Tokyo and teach SMR there. Due to his advanced age Shiraishi declined to come in person and sent his student Shimizu Takaji instead. Shimizu arrived in Tokyo in 1927. After a further demonstration of SMR-Jō in front of the Tokyo Police Force technical commission, a decision was made to incorporate elements of SMR-Jō for police-use. The new system was named keijo-jutsu and intended for use with the special police unit tokubetsu keibitai. Shimizu started training the new unit in 1931. Now a permanent Tokyo-resident, Shimizu opened up his own dojo, the Mumon (No Gate) Dojo.

During the 1930s, Shimizu came to believe that the old way of teaching were not enough to satisfy modern demands and the increasing number of new students. He took inspiration from Jigoro Kanos new Judo organisation and training-methods in order to, among other things, develop the twelve basic techniques kihon

During the 1930s, Shimizu came to believe that the old way of teaching were not enough to satisfy modern demands and the increasing number of new students. He took inspiration from Jigoro Kanos new Judo organisation and training-methods in order to, among other things, develop the twelve basic techniques kihon

which would make SMR more appealing and approachable to the beginner-student. In 1940 Shimizu became the head of the Dai Nihon Jōdokai (Greater Japan Jōdo Association) and he decided to rename the art from Jōjutsu to Jōdo in keeping with the trend of the time.

Creation of the kihon

(entry to come)

With the end of World War II in 1945, many martial arts were banned by the new government for fear that they might be used by ultra-nationalistic groups as a way to cause civil unrest. The police-jō taught by Shimizu to the Tokyo Police force was one of the few exceptions and many other martial arts practitioners from before the war went to Shimizus dojo in Tokyo for training. The police-jo were further developed in the 1960s when it was adapted for use in crowd-control with the Tokyo Riot police.

Creation of Seitei Jodo

(entry to come)

Shimizu, as had Shiraishi before him, has both been described as an SMR Headmaster due to their initiative and major contributions to SMR though neither Shiraishi or Shimizu received official appointment to such a position. Shimizu would complete Shintō Musō-ryū's transition from a localized bugei ryu to a national martial art and become the art's greatest popularizer through his acceptance of foreign students and the establishment of Jōdo-organisations.

After Shimizu's death, Kaminoda Tsunemori

, one of Shimizu's top-students and Menkyo Kaiden of Shintō Musō-ryū, took over as head-instructor of the Zoshokan Temple Dojo which would also become the new headquarters of the latters Nihon Jōdokai organisation.

The original tradition as founded by Gonnosuke was named Shintō Musō-ryū, with Shintō interpreted as "True Path" (真道). The first split resulted in another tradition being founded, also with the name "Shintō Musō-ryū" but with Shintō being interpretet as "New Just" (新當).

At a later point in history the originator of the lineage in the official documents of the ryū (densho) was changed from Matsumoto Bizen-no-Kami Naokatsu (founder of Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū and Kashima Shinryū) to the founder of Katori Shinto-ryū Iizasa Ienao

, a school in which Musō Gonnosuke had trained in. The actual founder of the Jōjutsu-tradition was Musō Gonnosuke.

The modern-day tradition, after the fall of the samurai era, uses the "Way of the gods" (神道) interpretation of Shinto ( Musō-ryū).

Notes

From the end of the Samurai reign in 1877 to the early 20th century, SMR was still largely confined, (though slowly spreading), to Fukuoka city on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu where the art first was created and thrived. The main proponent of SMR in Fukuoka during this time was Shiraishi Hanjiro, a former Kuroda-clan warrior (ashigaru

), who had trained in and received a joint-license from the two largest surviving jo-branches of SMR. Among Shiraishis top students were Shimizu Takaji, Otofuji Ichizô and Takayama Kiroku, Takayama being the senior. After receiving an invitation from the Tokyo martial arts scene to perform a demonstration of SMR, Shimizu and Takayama established a Tokyo SMR-group which held a close working relationship with martial arts supporters such as Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo. Shiraishi died in 1927 and there now existed two main lines (or branches) of SMR. The oldest of the two was found in Fukuoka, now under the leadership of Otofuji with the one in Tokyo under Shimizu. Takayama, the senior of the three students of Shiraishi, died in the 1930s leaving Shimizu with a position of great influence in the SMR-scene as the senior-most student of Shiriashi, (Otofuji being his junior), that would last up to his death in 1978. Although Otofuji was one of Shiraishis top-students he was unable to assume the role that Shimizu had held in Tokyo. By the 1970s the Tokyo and Fukuoka SMR-communities had fully developed into separate branches with their own leaders. Unlike Otofuji, Shimizu was a senior of both the Fukuoka and Tokyo SMR, with great knowledge and influence over both. With Shimizus death Otofuji were not in a strong enough position to claim complete authority over the SMR-community and no sort of agreement could be made over who should formally succeed Shimizu. The position of Headmaster of the SMR-community as a whole could not be filled. Otofuji would remain the leader of Kyushu SMR until his death in 1998.

From these two lineages, the Fukuoka and the Tokyo, there stems today several SMR-based organisations all over the world. One of the largest is the All-Japan Jodo Federation (ZNJR), established in the 1960s as a branch of the All-Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR). The ZNJR was established to further promote Jo through the teaching of ZNKR Jodo, also called Seitei Jodo. Seitei Jodo remains the most widespread form of Jo in the world today.

who had trained in the martial arts since boyhood, first in his native country then during the 1950s and onward in Japan. Donn Draeger was the first foreign student of Jodo and was also the first to train in the older Katori Shinto-ryū tradition. The IJF held a close cooperation with several high-ranking SMR-practitioners in the west, mainly from United States, Australia and Europe.

In Europe the first organisation dedicated to the promotion and teaching of the SMR tradition appeared in the late 1970s. starting witha small group based in Switzerland

headed by Pascal Krieger. Krieger started training Jodo under Shimizu Takaji in the late 1960s and introduced the tradition to his native country in the early 1970s. As the group in Switzerland slowly grew so did the number of members from the other European countries including Germany and France. In November 1979 "Helvetic Jôdô Association" was created with its headquarter in Geneva, and many new students started to arrive regularly to Geneve for training. The new organisation quickly grew beyond its boundaries and taking on a multi-border role with many of the qualified teachers returning to their homecountries and establishing new SMR-groups. In 1983 the first steps towards a European Jôdô Federation was taken by Krieger with the aim of supporting and developing the SMR-groups all over Europe. The restructoring of the European SMR-groups and slow buildup of an administration would take 7 years and in 1990 the organisation was officially recognised.

(more to come)

. Shintō Musō-ryū Jōdo, like many other ryu such as Katori Shinto-ryū, was temporary banned and forbidden to be taught. The occupation forces were weary of the nationalistic overtunes of some of these ryu and feared it would be used as a political tool for extreme-right nationalists. Jōdo, or rather elements of Jōdo, got a special reprive once the occupation forces decided it was useful in the new administration of Japan, more specifically in the Tokyo riot-police department. The number of headmasters is counted by combining all the known headmasters of all the branches of Shintō Musō-ryū Jōdo including the founder of Katori Shinto-ryū and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū. Gonnosuke trained in the KSR and received a full license.

The art was founded by the samurai

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

Musō Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi

Muso Gonnosuke

Musō Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi was a samurai of the early 17th century and the traditional founder of the Koryu school of jojutsu known as Shintō Musō-ryū...

(夢想 權之助 勝吉, fl.

Floruit

Floruit , abbreviated fl. , is a Latin verb meaning "flourished", denoting the period of time during which something was active...

c.1605, dates of birth and death unknown) in the early Edo period (1603–1868) and, according to legend, first put to use in a duel

Duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.Duels in this form were chiefly practised in Early Modern Europe, with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period especially among...

with Miyamoto Musashi

Miyamoto Musashi

, also known as Shinmen Takezō, Miyamoto Bennosuke or, by his Buddhist name, Niten Dōraku, was a Japanese swordsman and rōnin. Musashi, as he was often simply known, became renowned through stories of his excellent swordsmanship in numerous duels, even from a very young age...

(宮本 武蔵, 1584–1645). The original art created by Musō Gonnosuke has evolved and been added upon ever since its inception and up to modern times. The art was successfully brought outside of its original domain in Fukuoka

Fukuoka Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located on Kyūshū Island. The capital is the city of Fukuoka.- History :Fukuoka Prefecture includes the former provinces of Chikugo, Chikuzen, and Buzen....

and outside of Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

itself in the 19th and 20th century. The spreading of Shintō Musō-ryū beyond Japan was largely the effort of Takaji Shimizu (Shimizu Takaji, 1896–1978), considered the 25th headmaster. With the assistance of his own students and the cooperation of the kendo

Kendo

, meaning "Way of The Sword", is a modern Japanese martial art of sword-fighting based on traditional Japanese swordsmanship, or kenjutsu.Kendo is a physically and mentally challenging activity that combines strong martial arts values with sport-like physical elements.-Practitioners:Practitioners...

community, Shimizu spread Shintō Musō-ryū worldwide.

Musō Gonnosuke - Founder

Warring States Period

The Warring States Period , also known as the Era of Warring States, or the Warring Kingdoms period, covers the Iron Age period from about 475 BC to the reunification of China under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC...

(1467–1615), which had scarred Japan for almost 150 years, came to an end with the establishment of the authoritarian Tokugawa shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

. This in turn ushered in an era of peace that would last for over 260 years and ended with the overthrow of the shogunate in 1868. The relatively peaceful Edo period

Edo period

The , or , is a division of Japanese history which was ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family, running from 1603 to 1868. The political entity of this period was the Tokugawa shogunate....

took away the means of the samurai

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

to fully develop and test their skills in actual battlefield combat. The role of the samurai would eventually change from being warriors, constantly fighting battles for their liege lord (daimyo

Daimyo

is a generic term referring to the powerful territorial lords in pre-modern Japan who ruled most of the country from their vast, hereditary land holdings...

), into the role of providing internal security with increasingly more bureaucratic duties. Instead of fighting the frequent wars

History of Japan

The history of Japan encompasses the history of the islands of Japan and the Japanese people, spanning the ancient history of the region to the modern history of Japan as a nation state. Following the last ice age, around 12,000 BC, the rich ecosystem of the Japanese Archipelago fostered human...

and battles of the old days, with the exception of the siege of Osaka

Siege of Osaka

The was a series of battles undertaken by the Tokugawa shogunate against the Toyotomi clan, and ending in that clan's destruction. Divided into two stages , and lasting from 1614 to 1615, the siege put an end to the last major armed opposition to the shogunate's establishment...

in 1615 and the Shimabara Rebellion

Shimabara Rebellion

The was an uprising largely involving Japanese peasants, most of them Catholic Christians, in 1637–1638 during the Edo period.It was one of only a handful of instances of serious unrest during the relatively peaceful period of the Tokugawa shogunate's rule...

in 1637, many samurai resorted to duelling other samurai with others going on the road as a wandering swordsman to test their skills against other swordsmen such as bandits and ronin

Ronin

A or rounin was a Bushi with no lord or master during the feudal period of Japan. A samurai became masterless from the death or fall of his master, or after the loss of his master's favor or privilege....

, and some would train in far away schools (ryū

Ryu

* Ryū , a school of thought or discipline ., a book by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa* Ryū , a series by Masao Yajima and Akira Oze* Ryu , a common Korean family name...

) to hone their skill.

Musha shugyo

is a samurai warrior's quest or pilgrimage. The concept is similar to Knight Errantry in feudal Europe. A warrior, called a shugyōsha, would wander the land practicing and honing his skills without the protection of his family or school. Possible activities include training with other schools,...

) was Musō Gonnosuke, a samurai with considerable martial arts experience. Gonnosuke used his training in the arts of the sword (kenjutsu

Kenjutsu

, meaning "the method, or technique, of the sword." This is opposed to kendo, which means the way of the sword. Kenjutsu is the umbrella term for all traditional schools of Japanese swordsmanship, in particular those that predate the Meiji Restoration...

), glaive

Glaive

A glaive is a European polearm weapon, consisting of a single-edged blade on the end of a pole. It is similar to the Japanese naginata and the Chinese Guan Dao....

(naginatajutsu

Naginatajutsu

is the Japanese martial art of wielding the . This is a weapon resembling the medieval European glaive. Most naginatajutsu practiced today is in a modernized form, a gendai budō, in which competitions also are held.-Debated origins:...

), spear (sōjutsu

Sojutsu

, meaning "art of the spear" is the Japanese martial art of fighting with the Japanese .-Origins:Although the spear had a profound role in early Japanese mythology, where the islands of Japan themselves were said to be created by salt water dripping from the tip of a spear, as a weapon the first...

), and staff (bōjutsu

Bojutsu

, translated from Japanese as "staff technique", is the martial art of using a staff weapon called bō which simply means "staff". Staffs are perhaps one of the earliest weapons used by humankind. They have been in use for thousands of years in Eastern Asia. Some techniques involve slashing,...

), which he acquired from his studies in Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu

is one of the oldest extant Japanese martial arts, and an exemplar of koryū bujutsu. The Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū was founded by Iizasa Ienao, born 1387 in Iizasa village , who was living near Katori Shrine at the time...

and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū

Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryu

, often referred to simply as Jikishinkage-ryū or Kashima Shinden, is a traditional school of the Japanese martial art of swordsmanship...

, to develop a new way of handling the jō in combat.

Gonnosuke was said to have fully mastered the secret form called The Sword of One Cut (Ichi no Tachi), a form that were developed by the founder of the Kashima Shinto-ryū

Kashima Shinto-ryu

' is a traditional school of Japanese martial arts founded by Tsukahara Bokuden in the Muromachi period .Due to its formation during the tumultuous Sengoku Jidai, a time of feudal war, the school's techniques are based on battlefield experience and revolve around finding weak points in the...

and later spread to other Kashima schools such as Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū and Kashima Shin-ryū. His experiences, which would climax in his duels with the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, was the main event which led him create a set of techniques for the jō and establish a new school which he named Shintō Musō-ryū. The techniques were intended to be used against an opponent armed with either one or two swords. Among the advantages of the jō is its superior length when matched against a sword. The extra length enables the wielder to keep the swordman at a disadvantage and this is frequently applied in SMR.

The legend states that Musō Gonnosuke fought two duels with Miyamoto Musashi and was defeated in the first but victorious in the second, using his newly developed jōjutsu techniques to either defeat Musashi or force the duel into a draw. The first duel is described in the annals known as Niten Ki, which is a list of anecdotes told about Musashi and compiled by Musashi's followers after his death. The Niten Ki describes the first duel to have taken place c.1610. One of several legends states that after his defeat he withdrew to the Homan-zan mountain in the northern part of Kyushu and spent his days meditating, training and underwent austere religious rituals. While resting near a fire in a certain temple, Gonnosuke heard a voice say "Be mindful of the strategy 'the moon reflected in the water' (suigetsu)". The tradition states that was his inspiration to develop his new techniques and go fight Musashi a second time.

After the creation of his jō techniques and his establishment as a skilled jōjutsu practitioner he was invited by the Kuroda

Kuroda

-People:*Aki Kuroda , Japanese painter*Chris Kuroda, former lighting designer and operator for the band Phish*Emily Kuroda, actress*Fukumi Kuroda , Japanese actress...

clan

Japanese clans

This is a list of Japanese clans. The ancient clans mentioned in the Nihonshoki and Kojiki lost their political power before the Heian period. Instead of gozoku, new aristocracies, Kuge families emerged in the period...

of northern Kyūshū

Kyushu

is the third largest island of Japan and most southwesterly of its four main islands. Its alternate ancient names include , , and . The historical regional name is referred to Kyushu and its surrounding islands....

(in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture

Fukuoka Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located on Kyūshū Island. The capital is the city of Fukuoka.- History :Fukuoka Prefecture includes the former provinces of Chikugo, Chikuzen, and Buzen....

) to teach his jōjutsu to their warriors. Gonnosuke accepted the invitation and settled there.

The secret art of the Kuroda clan (1614–1871)

After Gonnosuke's death, his jōjutsu would become a closely guarded secret (oteme-waza) of the Kuroda clan, and forbidden to be taught anywhere but within its domain and only to specially selected people within the warrior-class. This was not an unusual practice in the Edo period. For example, in the 17th century, the Kage-ryūKage-ryu

is a Japanese koryu martial art founded in the late Muromachi period ca 1550 by Yamamoto Hisaya Masakatsu.The system teaches battojutsu using very long swords known as choken....

school of swordsmanship (battōjutsu

Battojutsu

is a Japanese term meaning techniques for engaging a sword. It is often used interchangeably with the terms iaijutsu, battōdō, or iaidō, although each term does have nuances in the Japanese language and different schools of Japanese martial arts may use them to differentiate between techniques...

) , used swords which were longer than the length legally permitted by the Tokugawa Shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

. As a result, Kage-ryū went "underground" , but was kept active in strict secrecy until the Meiji Restoration

Meiji Restoration

The , also known as the Meiji Ishin, Revolution, Reform or Renewal, was a chain of events that restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868...

hundreds of years later.

The main students of Gonnosuke's jōjutsu were the men charged with policing the Kuroda clan's domain (Kuroda-han). Several other schools (ryū

Ryu

* Ryū , a school of thought or discipline ., a book by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa* Ryū , a series by Masao Yajima and Akira Oze* Ryu , a common Korean family name...

) were created and taught in the Kuroda-han and in the various branches of the Shintō Musō-ryū system. During this period, two newly created schools which included the art of the police truncheon

Truncheon

Truncheon may refer to:*Baton *Cutting , means of plant propagation used by gardeners*HMS Truncheon , a British submarine commissioned during Word War II and later sold to Israel...

(jūtte), (among other weapons), and the art of restraining a man with rope (hojōjutsu

Hojojutsu

Hojōjutsu or Nawajutsu, is the traditional Japanese martial art of restraining a person using cord or rope.Encompassing many different materials, techniques and methods from many different schools, Hojojutsu is a quintessentially Japanese art that is a unique product of Japanese history and...

), was taught within the branches of the Shintō Musō-ryū as a complement to the arresting (torite)-arts.

After Gonnosukes death the art was mainly transmitted by the "Dangyō-shiyaku" (men's arts instructor), though not all branches of the Kuroda staff-traditions used the title of Dangyō-shiyaku. The Dangyō-instructor position was, unlike the swordsmanship instructor (kagyō) a non-hereditary position within the hierarchy of the Samurai.

The Dangyō-instructor in the Kuroda-domain was the charged with teaching the lower ranking warriors (ashigaru) in the arts of the staff (jō), capturing/seizing/escaping (torite), gunnery (hōjutsu) and rope

Hojojutsu

Hojōjutsu or Nawajutsu, is the traditional Japanese martial art of restraining a person using cord or rope.Encompassing many different materials, techniques and methods from many different schools, Hojojutsu is a quintessentially Japanese art that is a unique product of Japanese history and...

(nawa) among other arts. The position of Dangyō-instructor lasted until the abolishment of the Samurai and the feudal system in the 1860-70's.

Over time there would arise seven different lineages from the main Shintō Musō-ryū system. These are collectively known as "The Staff of Kuroda" (Kuroda no jō). Of these seven branches and styles of Gonnosuke's jōjutsu, only two would survive the ending of Japan's feudal system in 1867 and the resulting socio-economic modernization, to be merged into a single line that is today the modern .

The first split in the SMR occurred after the death of the fourth headmaster (師範家 Headmaster) Higuchi Han'emon. The split was the result of one of his licensed (menkyo kaiden) students, Harada Heizo Nobusada, breaking away to establish the (later informally known as Kansai-ryū), while another licensed student Higuchi Han'emon continued the original "True Path" line (later known as Moroki-ryū).

For several years Gonnosukes art was passed on by these two lines. The "New Just" line continued until after the death of its headmaster Nagatomi Koshiro Hisatomo in 1772. Afterwards, the "New Just" line branched off into two separate traditions. The primary reason for this branching, though indirectly, was the result of a restructuring of the living and training quarters of the warriors at the Chikuzen

Chikuzen

Chikuzen may refer to:*Chikuzen Province, an old province of Japan*Chikuzen, Fukuoka, a present town in Japan...

castle. The low-ranking foot soldiers (ashigaru

Ashigaru

The Japanese ashigaru were foot-soldiers of medieval Japan. The first known reference to ashigaru was in the 1300s, but it was during the Ashikaga Shogunate-Muromachi period that the use of ashigaru became prevalent by various warring factions.-Origins:Attempts were made in Japan by the Emperor...

) and the junior officers (kashi) were relocated to two separate areas of Fukuoka, partially due to the difference in the social status of the two groups. Each group would create new centres of training in their respective areas. This led to the establishment of two new branches from the "New Just"-line of Jōjutsu, each under their own respective head instructor. These were named haruyoshi, led by Ono Kyusaku, and the other jigyo, led by Komori Seibei. The two branches were named after the two respective areas of the castle in which they trained.

These new branches, jigyo and haruyoshi, were a reality by the early 19th century, but even though separate, all three lines appear to have been very similar in terms of techniques. This was demonstrated when the jigyo Branch was broken with the death of its head instructor Fujimoto Heikichi in 1815. The jigyo found itself without a student with the full transmission of the tradition and without a successor from within its own organisation the line would have died out. However, Hatae Kyuhei, who held a full license in the haruyoshi branch, would eventually revive the jigyo branch and allow it to continue into the Meiji Period

Meiji period

The , also known as the Meiji era, is a Japanese era which extended from September 1868 through July 1912. This period represents the first half of the Empire of Japan.- Meiji Restoration and the emperor :...

(1868–1912).

Meanwhile, the "True Path" had also fallen onto hard times as the tradition was broken with the death of Inoue Ryosuke in 1831. The similarities between the various "Staff of Kuroda"-traditions were again made clear when Hatae Kyuhei (who was an exponent of the haruyoshi-branch and had also helped revive the jigyo branch of the "New Just line") revived the "True Path". The "True Path" would, however, become extinct in the Bakumatsu era (1850–1867).

It was not until 1871 that the ban on teaching outside the Kuroda clan was lifted.

Shirashi Hanjiro and the Post-Kuroda-period - (1871–1927)

Meiji Restoration

The , also known as the Meiji Ishin, Revolution, Reform or Renewal, was a chain of events that restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868...

and easing of bureaucratic restrictions

Abolition of the han system

The was an act, in 1871, of the new Meiji government of the Empire of Japan to replace the traditional feudal domain system and to introduce centralized government authority . This process marked the culmination of the Meiji Restoration in that all daimyo were required to return their authority...

, it meant that now Shintō Musō-ryū (and many more martial arts) was allowed to be taught outside the traditional family lands.

It also meant that the numerous benefits of the traditional clan

Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clan members may be organized around a founding member or apical ancestor. The kinship-based bonds may be symbolical, whereby the clan shares a "stipulated" common ancestor that is a...

system was abolished along with it, and the numerous menkyo holders of SMR, who had lived, worked and trained with the financial support of the Daimyo

Daimyo

is a generic term referring to the powerful territorial lords in pre-modern Japan who ruled most of the country from their vast, hereditary land holdings...

(aristocratic landowners), would scatter and had to make a new living for themselves. The abolishment of the warrior-caste and the feudal-system led to a rapid modernisation of Japan. During this era many of the old bushi (warriors of all ranks) abandoned martial arts training altogether as it represented an era that was now gone. Throughout Japan most of the surviving traditions were kept alive, if only barely, by the former samurai and other individuals, who now had to find a new place in the new Japan which frowned upon the old martial way. Some of the old ryu were better off than others in the transition by not being overly dependent on government sponsorship.

During this transition-period and beyond various groups of former Kuroda bushi held sporadic meetings and training sessions in memory of the now bygone era. The old bushi present at these sessions included Uchida Ryogoro, Shiraishi Hanjiro and many of the former Dangyo (instructors) of the Kuroda clan. Due to newfound cooperation between the surviving SMR-lineages there were several joint-licenses of the Haruyoshi and Jigyo-branches of SMR issued with Shiraishi Hanjiro Shigeaki receiving a full Menkyo Kaiden license in the late 19th century. By the end of the Meiji era, (1912), only Shiraishi was still active as a fully qualified exponent and dedicated teacher of the last two remaining Kuroda Jō lineages. Shiraishi's dojo was located in Hakata

Hakata

Hakata may refer to:*Hakata-ku, Fukuoka, a ward in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan.**Hakata ningyō , traditional Japanese clay dolls, originally from Hakata*Hakata Station, a large train station in Fukuoka...

, a city that was merged with Fukuoka. Shiraishi would teach Shintō Musō-ryū in there until his death in 1927.

Shiraishis senior, Uchida Ryogoro

Uchida Ryogoro

Uchida Ryōgorō Shigeyoshi , , was a Japanese jojutsu practitioner, ranked menkyo in the Japanese martial art of Shintō Musō-ryū...

, decided to travel to Tokyo and teach and expand the art there while Shiraishi stayed in the designated Shintō Musō-ryū headquarters in Fukuoka.

Shiraishi Hanjiro was born in 1842 and was a lower class bushi. As a bushi he learned jojutsu, kenjutsu and other warrior-arts as was expected of a samurai. After the fall of the samurai government, Shiraishi did his best to sustain the jojutsu tradition he had learned. He helped organise the post-samurai meetings and training-sessions of old Kuroda-warriors and would receive his full license in SMR-jojutsu during one of these sessions. Shiraishi eventually opened up a dojo in Fukuoka City and taught the art there. Sometime in the late 19th century, Shiraishi started learning the art of Kusarigama (chain and sickle weapon) as taught by the Isshin-ryū tradition. He would eventually receive a Menkyo Kaiden in this system and started teaching kusarigamajutsu alongside jojutsu in his Fukuoka dojo. Shiraishi would award Menkyo Kaiden to several of his jojutsu students who carried on the tradition as a side-art to SMR-jojutsu.

In the early 20th century Uchida Ryogoro arrived in Tokyo and set up shop, teaching jōjutsu to high-rankers in the Japanese society at the time. His students included Nakayama Hakudo

Nakayama Hakudo

, also known as Nakayama Hiromichi, was a Japanese martial artist and founder of the iaidō style Musō Shinden-ryū. He is the only person to have received both jūdan and hanshi ranks in kendō, iaidō, and jōdō from the All Japan Kendo Federation...

(1873–1958), founder of Muso Shinden-ryū

Muso Shinden-ryu

is a iaijutsu koryū founded by Nakayama Hakudō , last sōke of the Shimomura branch of Hasegawa Eishin-ryū. The term "iaidō" appeared in 1932 and was popularized by Nakayama Hakudō .-Particularities:...

and Komita Takayoshi, founder of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai

Dai Nippon Butoku Kai

is a Japanese martial arts organization established in 1895 in Kyoto, Japan, under the authority of the Ministry of Education and sanction of the Emperor Meiji. Its purpose, at that time, was to standardize martial disciplines and systems throughout Japan. This was the first official martial arts...

("Great Japan Budō Preservation Society"). It was during this time that Jigoro Kano were first invited to Fukuoka to observe SMR which would herald the cooperation between the two arts in Tokyo. Uchida Ryogoro also taught at the Naval Officers Club and later at the Shiba Kōen park. Ryogoro's son, Uchida Ryōhei, joined him in Tokyo and studied under his father there and was instrumental in developing his father's Tanjōjutsu art

Uchida Ryu Tanjojutsu

, also known as Sutekki-Jutsu, is a Japanese martial arts school of tanjojutsu, originally devised by Shinto Muso-ryu practicitioner Uchida Ryogoro as a way to utilize the western-style walking stick into a weapon of self-defence...

into a working set of techniques. Uchida Ryogoro died in 1921. Uchidas efforts in Tokyo greatly assisted in establishing a connection with the various martial arts communities already based in Tokyo and would help pave the way Shimizu Takajis own efforts at popularizing SMR and establishing a new SMR presence.

Shintō Musō-ryū and Shimizu Takaji - (1927–1978)

Hakata

Hakata may refer to:*Hakata-ku, Fukuoka, a ward in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan.**Hakata ningyō , traditional Japanese clay dolls, originally from Hakata*Hakata Station, a large train station in Fukuoka...

, where the Shiraishi Dojo operated. Shimizu started his training at the age of 17 under Shiraishi and quickly rose in the ranks, receiving the mokuroku scroll in 1918 and the license of full transmission (Menkyo kaiden) in 1920 at the age of 23. Of the many students of Shiraishi there were three who became prominent in the aftermath of Shiraishi's death. Shimizu Takaji, Takayama Kiroku and Otofuji Ichizo.

In 1929 Takayama Kiroku with financial aid from Shiraishis family opened a dojo in Fukuoka and was named Shihan with Shimizu named fuku-shihan or "assistant master". Shimizu by this time, however, was on his way to Tokyo in order to teach Jōdo. Takayama died within a few years after the opening of the Fukuoka dojo and Otofuji Ichizo took over as the new master of the dojo and of the Fukuoka-jō, a responsibility he held until his death in 1998.

Judo

is a modern martial art and combat sport created in Japan in 1882 by Jigoro Kano. Its most prominent feature is its competitive element, where the object is to either throw or takedown one's opponent to the ground, immobilize or otherwise subdue one's opponent with a grappling maneuver, or force an...

, witnessed a demonstration of SMR and made an invitation to Shiraishi come to Tokyo and teach SMR there. Due to his advanced age Shiraishi declined to come in person and sent his student Shimizu Takaji instead. Shimizu arrived in Tokyo in 1927. After a further demonstration of SMR-Jō in front of the Tokyo Police Force technical commission, a decision was made to incorporate elements of SMR-Jō for police-use. The new system was named keijo-jutsu and intended for use with the special police unit tokubetsu keibitai. Shimizu started training the new unit in 1931. Now a permanent Tokyo-resident, Shimizu opened up his own dojo, the Mumon (No Gate) Dojo.

Kihon

is a Japanese term meaning "basics" or "fundamentals." The term is used to refer to the basic techniques that are taught and practiced as the foundation of most Japanese martial arts....

which would make SMR more appealing and approachable to the beginner-student. In 1940 Shimizu became the head of the Dai Nihon Jōdokai (Greater Japan Jōdo Association) and he decided to rename the art from Jōjutsu to Jōdo in keeping with the trend of the time.

Creation of the kihon

(entry to come)

With the end of World War II in 1945, many martial arts were banned by the new government for fear that they might be used by ultra-nationalistic groups as a way to cause civil unrest. The police-jō taught by Shimizu to the Tokyo Police force was one of the few exceptions and many other martial arts practitioners from before the war went to Shimizus dojo in Tokyo for training. The police-jo were further developed in the 1960s when it was adapted for use in crowd-control with the Tokyo Riot police.

Creation of Seitei Jodo

(entry to come)

Shimizu, as had Shiraishi before him, has both been described as an SMR Headmaster due to their initiative and major contributions to SMR though neither Shiraishi or Shimizu received official appointment to such a position. Shimizu would complete Shintō Musō-ryū's transition from a localized bugei ryu to a national martial art and become the art's greatest popularizer through his acceptance of foreign students and the establishment of Jōdo-organisations.

Post-Shimizu period 1978 to the present

(work in progress)After Shimizu's death, Kaminoda Tsunemori

Shinto Muso-ryu

, most commonly known by its practice of jōdō, is a traditional school of the Japanese martial art of jōjutsu, or the art of wielding the short staff . The technical purpose of the art is to learn how to defeat a swordsman in combat using the jō, with an emphasis on proper combative distance,...

, one of Shimizu's top-students and Menkyo Kaiden of Shintō Musō-ryū, took over as head-instructor of the Zoshokan Temple Dojo which would also become the new headquarters of the latters Nihon Jōdokai organisation.

Shintō Musō-ryū lineage chart

From the foundation of the art in the early 17th century to the start of the Meiji-era there has been a total of seven traditions of Kuroda no Jô within the Kuroda domain including two branches. Five of these used the name "Shintō Musō-ryū", but with different interpretations of Shintō. The other two traditions, which are not covered in the below chart, were "Ten'ami-ryū Heijo" and the "Shin Chigiriki-ryū".The original tradition as founded by Gonnosuke was named Shintō Musō-ryū, with Shintō interpreted as "True Path" (真道). The first split resulted in another tradition being founded, also with the name "Shintō Musō-ryū" but with Shintō being interpretet as "New Just" (新當).

At a later point in history the originator of the lineage in the official documents of the ryū (densho) was changed from Matsumoto Bizen-no-Kami Naokatsu (founder of Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū and Kashima Shinryū) to the founder of Katori Shinto-ryū Iizasa Ienao

Iizasa Ienao

was the founder of Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū which is a traditional Japanese martial art. His Buddhist posthumous name is Taiganin-den-Taira-no-Ason-Iga-no-Kami-Raiodo-Hon-Daikoji....

, a school in which Musō Gonnosuke had trained in. The actual founder of the Jōjutsu-tradition was Musō Gonnosuke.

The modern-day tradition, after the fall of the samurai era, uses the "Way of the gods" (神道) interpretation of Shinto ( Musō-ryū).

| Shintō Musō-ryū tradition - Founded early 1600s |

|---|

|

| The "New Just" 新當 (Shintō) Musō-ryū tradition |

The "True Path" 真道 (Shintō ) Musō-ryū tradition- Later known as Moroki-ryū |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

| Haruyoshi branch |

Jigyo branch |

The "True Path" 真道 (Shintō) Musō-ryū tradition- Later known as Moroki-ryū |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

"Way of the gods" 神道 (Shintō) Musō-ryū - late 19th century to present time

|

|---|

|

|

Notes

- Menkyo=A holder of a license of total transmission with complete authority to teach and/or modify the existing system.

- Kanji and names:

- Original name: 真道, (interpreted as "True Path" pronounced "Shinto"), Muso-ryū 夢想流.

- Branch schools: 新當, (interpreted as "New Just", pronounced "Shinto"), Muso-ryū 夢想流.

- Modern-day tradition: 神道, (interpreted as "Way of the Gods" pronounced "Shinto"), Muso-ryū 夢想流.

Past and modern organisations

After the death of Shimizu Takaji in 1978, SMR in Tokyo was left without a clear leader or appointed successor. This led to a splintering of the SMR dojos in Japan, and eventually all over the world. With no single organisation or individual with complete authority over SMR as a whole, several of the various fully licensed (menkyo) SMR-practitioners established their own organisations both in the West and in Japan.From the end of the Samurai reign in 1877 to the early 20th century, SMR was still largely confined, (though slowly spreading), to Fukuoka city on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu where the art first was created and thrived. The main proponent of SMR in Fukuoka during this time was Shiraishi Hanjiro, a former Kuroda-clan warrior (ashigaru

Ashigaru

The Japanese ashigaru were foot-soldiers of medieval Japan. The first known reference to ashigaru was in the 1300s, but it was during the Ashikaga Shogunate-Muromachi period that the use of ashigaru became prevalent by various warring factions.-Origins:Attempts were made in Japan by the Emperor...

), who had trained in and received a joint-license from the two largest surviving jo-branches of SMR. Among Shiraishis top students were Shimizu Takaji, Otofuji Ichizô and Takayama Kiroku, Takayama being the senior. After receiving an invitation from the Tokyo martial arts scene to perform a demonstration of SMR, Shimizu and Takayama established a Tokyo SMR-group which held a close working relationship with martial arts supporters such as Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo. Shiraishi died in 1927 and there now existed two main lines (or branches) of SMR. The oldest of the two was found in Fukuoka, now under the leadership of Otofuji with the one in Tokyo under Shimizu. Takayama, the senior of the three students of Shiraishi, died in the 1930s leaving Shimizu with a position of great influence in the SMR-scene as the senior-most student of Shiriashi, (Otofuji being his junior), that would last up to his death in 1978. Although Otofuji was one of Shiraishis top-students he was unable to assume the role that Shimizu had held in Tokyo. By the 1970s the Tokyo and Fukuoka SMR-communities had fully developed into separate branches with their own leaders. Unlike Otofuji, Shimizu was a senior of both the Fukuoka and Tokyo SMR, with great knowledge and influence over both. With Shimizus death Otofuji were not in a strong enough position to claim complete authority over the SMR-community and no sort of agreement could be made over who should formally succeed Shimizu. The position of Headmaster of the SMR-community as a whole could not be filled. Otofuji would remain the leader of Kyushu SMR until his death in 1998.

From these two lineages, the Fukuoka and the Tokyo, there stems today several SMR-based organisations all over the world. One of the largest is the All-Japan Jodo Federation (ZNJR), established in the 1960s as a branch of the All-Japan Kendo Federation (ZNKR). The ZNJR was established to further promote Jo through the teaching of ZNKR Jodo, also called Seitei Jodo. Seitei Jodo remains the most widespread form of Jo in the world today.

International Jodo Federation

One of the first worldwide organisations was the "International Jôdô Federation" (IJF), founded by martial artist Donald "Donn" Draeger(1922–1982) and Shimizu Takaji in the 1970s with the aim of spreading SMR beyond the Japanese boundaries. Donn Draeger was an US Captain of the United States Marine CorpsUnited States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps is a branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for providing power projection from the sea, using the mobility of the United States Navy to deliver combined-arms task forces rapidly. It is one of seven uniformed services of the United States...

who had trained in the martial arts since boyhood, first in his native country then during the 1950s and onward in Japan. Donn Draeger was the first foreign student of Jodo and was also the first to train in the older Katori Shinto-ryū tradition. The IJF held a close cooperation with several high-ranking SMR-practitioners in the west, mainly from United States, Australia and Europe.

In Europe the first organisation dedicated to the promotion and teaching of the SMR tradition appeared in the late 1970s. starting witha small group based in Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

headed by Pascal Krieger. Krieger started training Jodo under Shimizu Takaji in the late 1960s and introduced the tradition to his native country in the early 1970s. As the group in Switzerland slowly grew so did the number of members from the other European countries including Germany and France. In November 1979 "Helvetic Jôdô Association" was created with its headquarter in Geneva, and many new students started to arrive regularly to Geneve for training. The new organisation quickly grew beyond its boundaries and taking on a multi-border role with many of the qualified teachers returning to their homecountries and establishing new SMR-groups. In 1983 the first steps towards a European Jôdô Federation was taken by Krieger with the aim of supporting and developing the SMR-groups all over Europe. The restructoring of the European SMR-groups and slow buildup of an administration would take 7 years and in 1990 the organisation was officially recognised.

(more to come)

Footnotes

The names Shinto and Shindo, as used in Shintō Musō-ryū, are both equally correct. Different SMR-groups use the name Shinto or Shindo depending on their own tradition, no sort of consensus has been made as to which name should be used. Kage-ryū Battojutsu did survive the Meiji-restoration and is still active today. A more modern example of martial arts going underground and being secretly taught can be found in the post-World War II ban on Japanese martial arts by the US during its occupationOccupied Japan

At the end of World War II, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States with contributions also from Australia, India, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. This foreign presence marked the first time in its history that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power...

. Shintō Musō-ryū Jōdo, like many other ryu such as Katori Shinto-ryū, was temporary banned and forbidden to be taught. The occupation forces were weary of the nationalistic overtunes of some of these ryu and feared it would be used as a political tool for extreme-right nationalists. Jōdo, or rather elements of Jōdo, got a special reprive once the occupation forces decided it was useful in the new administration of Japan, more specifically in the Tokyo riot-police department. The number of headmasters is counted by combining all the known headmasters of all the branches of Shintō Musō-ryū Jōdo including the founder of Katori Shinto-ryū and Kashima Jikishinkage-ryū. Gonnosuke trained in the KSR and received a full license.

See also

- Bujutsu/budōBudois a Japanese term describing martial arts. In English, it is used almost exclusively in reference to Japanese martial arts.-Etymology:Budō is a compound of the root bu , meaning war or martial; and dō , meaning path or way. Specifically, dō is derived from the Buddhist Sanskrit mārga...

- The "Way of War" or the "Way of the warrior". - DaimyoDaimyois a generic term referring to the powerful territorial lords in pre-modern Japan who ruled most of the country from their vast, hereditary land holdings...

- The feudal landowner of feudal Japan. Employed samurai as warriors in a vassalFeudalismFeudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

/lordFeudalismFeudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

relationship to both protect and expand the Daimyos domains before and during the Sengoku Jidai period. The Daimyo as a position lasted until the Meiji restoration and abolishment of the feudal system. - koryūKoryuis a Japanese word that is used in association with the ancient Japanese martial arts. This word literally translates as "old school" or "traditional school"...

- A term used to describe Japanese martial arts created before the 1876 banning of the samurai sword. Any art created that was created post-1876, such as JudoJudois a modern martial art and combat sport created in Japan in 1882 by Jigoro Kano. Its most prominent feature is its competitive element, where the object is to either throw or takedown one's opponent to the ground, immobilize or otherwise subdue one's opponent with a grappling maneuver, or force an...

, KarateKarateis a martial art developed in the Ryukyu Islands in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It was developed from indigenous fighting methods called and Chinese kenpō. Karate is a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open-handed techniques such as knife-hands. Grappling, locks,...

, AikidoAikidois a Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba as a synthesis of his martial studies, philosophy, and religious beliefs. Aikido is often translated as "the Way of unifying life energy" or as "the Way of harmonious spirit." Ueshiba's goal was to create an art that practitioners could use to...

, TaidōTaidoTaidō is a Japanese martial art created in 1965 by Seiken Shukumine . The word taidō means "way of the body." Taidō has its roots in traditional Okinawan Karate...

, are considered to be Gendai budōGendai Budo, meaning "modern martial way", are modern Japanese martial arts which were established after the Meiji Restoration . Koryū are the opposite: ancient martial arts established before the Meiji Restoration.-Scope and tradition:...

. Karate, although preceding 1876, does not qualify as koryū due to the fact it did not evolve in Japan but on the Ryūkyū IslandsRyukyu IslandsThe , also known as the , is a chain of islands in the western Pacific, on the eastern limit of the East China Sea and to the southwest of the island of Kyushu in Japan. From about 1829 until the mid 20th century, they were alternately called Luchu, Loochoo, or Lewchew, akin to the Mandarin...

(modern Okinawa PrefectureOkinawa Prefectureis one of Japan's southern prefectures. It consists of hundreds of the Ryukyu Islands in a chain over long, which extends southwest from Kyūshū to Taiwan. Okinawa's capital, Naha, is located in the southern part of Okinawa Island...

) which did not become a part of Japan until the 17th century. - SamuraiSamuraiis the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

- The warrior elite of feudal Japan. The Samurai caste was abolished in the Meiji restoration's aftermath.- AshigaruAshigaruThe Japanese ashigaru were foot-soldiers of medieval Japan. The first known reference to ashigaru was in the 1300s, but it was during the Ashikaga Shogunate-Muromachi period that the use of ashigaru became prevalent by various warring factions.-Origins:Attempts were made in Japan by the Emperor...

- Originally the conscripted footsoldiers of Samurai-armies. After Tokugawa came into power they became professional soldiers and the lowest ranking samurai.

- Ashigaru