Jack Sheppard

Encyclopedia

Robbery

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take something of value by force or threat of force or by putting the victim in fear. At common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the person of that property, by means of force or fear....

, burglar

Burglary

Burglary is a crime, the essence of which is illicit entry into a building for the purposes of committing an offense. Usually that offense will be theft, but most jurisdictions specify others which fall within the ambit of burglary...

and thief

Theft

In common usage, theft is the illegal taking of another person's property without that person's permission or consent. The word is also used as an informal shorthand term for some crimes against property, such as burglary, embezzlement, larceny, looting, robbery, shoplifting and fraud...

of early 18th-century London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter but took to theft and burglary in 1723, with little more than a year of his training to complete. He was arrested and imprisoned five times in 1724 but escaped four times, making him a notorious public figure, and wildly popular with the poorer classes. Ultimately, he was caught, convicted, and hanged

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

at Tyburn

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

, ending his brief criminal career after less than two years. The inability of the notorious "Thief-Taker General" Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

to control Sheppard, and injuries suffered by Wild at the hands of Sheppard's colleague, Joseph "Blueskin" Blake

Blueskin

Joseph "Blueskin" Blake was an 18th century English highwayman and felon.-Early life:Blake was the son of Nathaniel and Jane Blake. He was baptised at All-Hallows-the-Great in London...

, led to Wild's downfall.

Sheppard was as renowned for his attempts to escape imprisonment as he was for his crimes. An autobiographical

Autobiography

An autobiography is a book about the life of a person, written by that person.-Origin of the term:...

"Narrative", thought to have been ghostwritten by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

, was sold at his execution, quickly followed by popular plays. The character of Macheath in John Gay

John Gay

John Gay was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for The Beggar's Opera , set to music by Johann Christoph Pepusch...

's The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of satirical ballad opera to remain popular today...

(1728) was based on Sheppard, keeping him in the limelight for over 100 years. He returned to the public consciousness around 1840, when William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth was an English historical novelist born in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in London he met the publisher John Ebers, at that time manager of the King's Theatre, Haymarket...

wrote a novel entitled Jack Sheppard

Jack Sheppard (novel)

Jack Sheppard is a novel by William Harrison Ainsworth serially published in Bentley's Miscellany from 1839 to 1840, with illustrations by George Cruikshank...

, with illustrations by George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reached an international audience.-Early life:Cruikshank was born in London...

. The popularity of his tale, and the fear that others would be drawn to emulate his behaviour, led the authorities to refuse to license

Licensing Act 1737

The Licensing Act or Theatrical Licensing Act of 21 June 1737 was a landmark act of censorship of the British stage and one of the most determining factors in the development of Augustan drama...

any plays in London with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years.

Early life

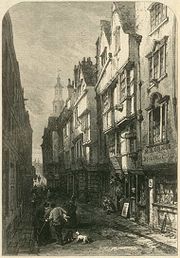

Sheppard was born in White's Row, in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

's Spitalfields

Spitalfields

Spitalfields is a former parish in the borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London, near to Liverpool Street station and Brick Lane. The area straddles Commercial Street and is home to many markets, including the historic Old Spitalfields Market, founded in the 17th century, Sunday...

. During the first two decades of the 18th century, Spitalfields was notorious for the presence of highwaymen and for being a tremendously economically depressed area, and so it is clear that his family was impoverished. He was baptised on 5 March, the day after he was born, at St Dunstan's, Stepney

St Dunstan's, Stepney

St Dunstan's, Stepney is an Anglican Church which stands on a site which has been used for Christian worship for over a thousand years. It is located in Stepney High Street, in Stepney, London Borough of Tower Hamlets.-History:...

, suggesting a fear of infant mortality

Infant mortality

Infant mortality is defined as the number of infant deaths per 1000 live births. Traditionally, the most common cause worldwide was dehydration from diarrhea. However, the spreading information about Oral Re-hydration Solution to mothers around the world has decreased the rate of children dying...

by his parents, perhaps because the newborn was weak or sickly. His parents named him after an older brother, John, who had died before his birth. In life, he was better known as Jack, or even "Gentleman Jack" or "Jack the Lad". He had a second brother, Thomas, and a younger sister, Mary. Their father, a carpenter

Carpenter

A carpenter is a skilled craftsperson who works with timber to construct, install and maintain buildings, furniture, and other objects. The work, known as carpentry, may involve manual labor and work outdoors....

, died while Sheppard was young, and his sister died two years later.

Workhouse

In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment...

near St Helen's Bishopsgate

St Helen's Bishopsgate

St Helen's Bishopsgate is a large conservative evangelical Anglican church, in Lime Street ward, in the City of London, close to the Lloyd's building and the 'Gherkin'.-History:...

, when he was six years old. Sheppard was sent out as a parish apprentice to a cane-chair maker, taking a settlement of 20 shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s, but his new master soon died. He was sent out to a second cane-chair maker, but Sheppard was treated badly. Finally, when Sheppard was 10, he went to work as a shop-boy for William Kneebone, a wool draper

Draper

Draper is the now largely obsolete term for a wholesaler, or especially retailer, of cloth, mainly for clothing, or one who works in a draper's shop. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher. The drapers were an important trade guild...

with a shop on the Strand

Strand, London

Strand is a street in the City of Westminster, London, England. The street is just over three-quarters of a mile long. It currently starts at Trafalgar Square and runs east to join Fleet Street at Temple Bar, which marks the boundary of the City of London at this point, though its historical length...

. Sheppard's mother had been working for Kneebone since her husband's death. Kneebone taught Sheppard to read and write and apprenticed him to a carpenter, Owen Wood, in Wych Street

Wych Street

Wych Street was a street in London, roughly where Australia House now stands on Aldwych. It ran west from the church of St Clement Danes on the Strand to a point towards the southern end of Drury Lane...

, off Drury Lane

Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster....

in Covent Garden

Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St. Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit and vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist site, and the Royal Opera House, which is also known as...

. Sheppard signed his seven-year indenture

Indenture

An indenture is a legal contract reflecting a debt or purchase obligation, specifically referring to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, an instrument used for commercial debt or real estate transaction.-Historical usage:An indenture is a...

on 2 April 1717.

By 1722, Sheppard was showing great promise as a carpenter. Aged 20, he was a small man, only 5'4" (1.63 m) and lightly built, but deceptively strong. He had a pale face with large, dark eyes, a wide mouth and a quick smile. Despite a slight stutter, his wit made him popular in the taverns of Drury Lane. He served five unblemished years of his apprenticeship but then began to be led into crime.

Joseph Hayne, a button-moulder who owned a shop nearby, also ran a tavern

Tavern

A tavern is a place of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food, and in some cases, where travelers receive lodging....

named the Black Lion off Drury Lane, which he encouraged the local apprentices to frequent. The Black Lion was visited by criminals such as Joseph "Blueskin" Blake

Blueskin

Joseph "Blueskin" Blake was an 18th century English highwayman and felon.-Early life:Blake was the son of Nathaniel and Jane Blake. He was baptised at All-Hallows-the-Great in London...

, Sheppard's future partner in crime, and self-proclaimed "Thief-Taker General" Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

, secretly the linchpin of a criminal empire across London and later Sheppard's implacable enemy.

According to Sheppard's "autobiography", he had been an innocent until going to Hayne's tavern, but there began an attachment to strong drink and the affections of Elizabeth Lyon, a prostitute also known as Edgworth Bess (or Edgeworth Bess) from her place of birth at Edgeworth

Edgware

Edgware is an area in London, situated north-northwest of Charing Cross. It forms part of both the London Borough of Barnet and the London Borough of Harrow. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London....

in Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

. In his History, Defoe records that Bess was "a main lodestone in attracting of him up to this Eminence of Guilt." Such, Sheppard claimed, was the source of his later ruin. Peter Linebaugh offers a different view: that Sheppard's sudden transformation was a liberation from the dull drudgery of indentured labour and that he progressed from pious servitude to self-confident rebellion and Levelling

Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement during the English Civil Wars which emphasised popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law, and religious tolerance, all of which were expressed in the manifesto "Agreement of the People". They came to prominence at the end of the First...

.

Criminal career

Sheppard threw himself into a hedonistic whirl of drinking and whoring. Inevitably, his carpentry suffered, and he became disobedient to his master. With Lyon's encouragement, Sheppard took to crime in order to compliment his legitimate wages. His first recorded theft was in Spring 1723, when he engaged in petty shopliftingShoplifting

Shoplifting is theft of goods from a retail establishment. It is one of the most common property crimes dealt with by police and courts....

, stealing two silver spoons while on an errand for his master to Rummer Tavern in Charing Cross

Charing Cross

Charing Cross denotes the junction of Strand, Whitehall and Cockspur Street, just south of Trafalgar Square in central London, England. It is named after the now demolished Eleanor cross that stood there, in what was once the hamlet of Charing. The site of the cross is now occupied by an equestrian...

. Sheppard's misdeeds went undetected, and he moved on to larger crimes, often stealing goods from the houses where he was working. Finally, he quit the employ of his master on 2 August 1723, with less than 2 years of his apprenticeship left, although he continued to work as a journeyman

Journeyman

A journeyman is someone who completed an apprenticeship and was fully educated in a trade or craft, but not yet a master. To become a master, a journeyman had to submit a master work piece to a guild for evaluation and be admitted to the guild as a master....

carpenter. He was not suspected of the crimes, and progressed to burglary

Burglary

Burglary is a crime, the essence of which is illicit entry into a building for the purposes of committing an offense. Usually that offense will be theft, but most jurisdictions specify others which fall within the ambit of burglary...

, falling in with criminals in Jonathan Wild's gang.

He moved to Fulham

Fulham

Fulham is an area of southwest London in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, SW6 located south west of Charing Cross. It lies on the left bank of the Thames, between Putney and Chelsea. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London...

, living as man and wife with Lyon at Parsons Green

Parsons Green

Parsons Green is an area in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham.The mainly residential area is named after the village green now called Parsons Green Park where the vicar of Fulham used to live...

, before moving to Piccadilly

Piccadilly

Piccadilly is a major street in central London, running from Hyde Park Corner in the west to Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is completely within the city of Westminster. The street is part of the A4 road, London's second most important western artery. St...

. When Lyon was arrested and imprisoned at St Giles's Roundhouse

St Giles's Roundhouse

The St Giles's Roundhouse was a small roundhouse or prison, mainly used to temporarily hold suspected criminals.It was located in the St Giles area of present-day central London, which - during the 17th and 18th centuries - was a 'rookery' notorious for its thieves and other criminals.The...

, the beadle

Beadle

Beadle, sometimes spelled "bedel," is a lay official of a church or synagogue who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational, or ceremonial duties....

, a Mr Brown, refused to let Sheppard visit, so he broke in and took her away.

Arrested and escaped twice

Sheppard was first arrested after a burglary he committed with his brother, Tom, and his mistress, Lyon, in Clare MarketClare Market

Clare Market was an area of London to the west of Lincoln's Inn Fields, between the Strand and Drury Lane, with Vere Street adjoining its western side...

on 5 February 1724. Tom, also a carpenter, had already been convicted once for stealing tools from his master the previous autumn and burned in the hand

Human branding

Human branding or stigmatizing is the process in which a mark, usually a symbol or ornamental pattern, is burned into the skin of a living person, with the intention that the resulting scar makes it permanent. This is performed using a hot or very cold branding iron...

. Tom was arrested again on 24 April 1724. Afraid that he would be hanged this time, Tom informed on Jack, and a warrant

Warrant (law)

Most often, the term warrant refers to a specific type of authorization; a writ issued by a competent officer, usually a judge or magistrate, which permits an otherwise illegal act that would violate individual rights and affords the person executing the writ protection from damages if the act is...

was issued for Jack's arrest.

Jonathan Wild was aware of Sheppard's thefts, as Sheppard had fenced

Fence (criminal)

A fence is an individual who knowingly buys stolen property for later resale, sometimes in a legitimate market. The fence thus acts as a middleman between thieves and the eventual buyers of stolen goods who may or may not be aware that the goods are stolen. As a verb, the word describes the...

some stolen goods through one of Wild's men, William Field. Wild asked another of his men, James Sykes (known as "Hell and Fury") to challenge Sheppard to a game of skittles

Skittles (sport)

Skittles is an old European lawn game, a variety of bowling, from which ten-pin bowling, duckpin bowling, and candlepin bowling in the United States, and five-pin bowling in Canada are descended. In the United Kingdom, the game remains a popular pub game in England and Wales, though it tends to be...

at Redgate's public house near Seven Dials

Seven Dials

Seven Dials is a small but well-known road junction in the West End of London in Covent Garden where seven streets converge. At the centre of the roughly-circular space is a pillar bearing six sundials, a result of the pillar being commissioned before a late stage alteration of the plans from an...

. Sykes betrayed Sheppard to a Mr Price, a constable

Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions.-Etymology:...

from the parish of St Giles

St Giles, London

St Giles is a district of London, England. It is the location of the church of St Giles in the Fields, the Phoenix Garden and St Giles Circus. It is located at the southern tip of the London Borough of Camden and is part of the Midtown business improvement district.The combined parishes of St...

, to gather the usual £40 reward for giving information leading to the conviction of a felon

Felony

A felony is a serious crime in the common law countries. The term originates from English common law where felonies were originally crimes which involved the confiscation of a convicted person's land and goods; other crimes were called misdemeanors...

. The magistrate, Justice Parry, had Sheppard imprisoned overnight on the top floor of St Giles's Roundhouse

St Giles's Roundhouse

The St Giles's Roundhouse was a small roundhouse or prison, mainly used to temporarily hold suspected criminals.It was located in the St Giles area of present-day central London, which - during the 17th and 18th centuries - was a 'rookery' notorious for its thieves and other criminals.The...

pending further questioning, but Sheppard escaped within three hours by breaking through the timber ceiling and lowering himself to the ground with a rope fashioned from bedclothes. Still wearing irons, Sheppard coolly joined the crowd that had been attracted by the sounds of him breaking out. He distracted their attention by pointing to the shadows on the roof and shouting that he could see the escapee, and then swiftly departed.

Leicester Square

Leicester Square is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. The Square lies within an area bound by Lisle Street, to the north; Charing Cross Road, to the east; Orange Street, to the south; and Whitcomb Street, to the west...

). He was detained overnight in St Ann's Roundhouse in Soho

Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster and part of the West End of London. Long established as an entertainment district, for much of the 20th century Soho had a reputation for sex shops as well as night life and film industry. Since the early 1980s, the area has undergone considerable...

and visited there the next day by Lyon; she was recognised as his wife and locked in a cell with him. They appeared before Justice Walters, who sent them to the New Prison

New Prison

The New Prison was a prison located in the Clerkenwell area of central London between c.1617 and 1877 ....

in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell is an area of central London in the London Borough of Islington. From 1900 to 1965 it was part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The well after which it was named was rediscovered in 1924. The watchmaking and watch repairing trades were once of great importance...

, but they escaped from their cell, known as the Newgate Ward, within a matter of days. By 25 May, Whitsun

Whitsun

Whitsun is the name used in the UK for the Christian festival of Pentecost, the seventh Sunday after Easter, which commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Christ's disciples...

Monday, Sheppard and Lyon had filed through their manacles; they removed a bar from the window and used their knotted bed-clothes to descend to ground level. Finding themselves in the yard of the neighbouring bridewell

Clerkenwell Bridewell

Clerkenwell Bridewell was a prison located in the Clerkenwell area, immediately north of the City of London , between c.1615 and 1794, when it was superseded by the nearby Coldbath Fields Prison in Mount Pleasant...

, they clambered over the 22-foot-high (6.7 m) prison gate to freedom. This feat was widely publicised, not least because Sheppard was only a small man, and Lyon was a large, buxom woman.

Third arrest, trial, and third escape

Sheppard's thieving abilities were admired by Jonathan Wild. Wild demanded that Sheppard surrender his stolen goods for Wild to fence, and so take the greater profits, but Sheppard refused. He began to work with Joseph "BlueskinBlueskin

Joseph "Blueskin" Blake was an 18th century English highwayman and felon.-Early life:Blake was the son of Nathaniel and Jane Blake. He was baptised at All-Hallows-the-Great in London...

" Blake, and they burgled Sheppard's former master, William Kneebone, on Sunday 12 July 1724. Wild could not permit Sheppard to continue outside his control and began to seek Sheppard's arrest. Unfortunately for Sheppard, his fence, William Field, was one of Wild's men. After Sheppard had a brief foray with Blueskin as highwaymen

Highwayman

A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads...

on the Hampstead Road on Sunday 19 July and Monday 20 July, Field informed on Sheppard to Wild. Wild believed Lyon would know Sheppard's whereabouts, so he plied her with drinks at a brandy shop near Temple Bar

Temple Bar, London

Temple Bar is the barrier marking the westernmost extent of the City of London on the road to Westminster, where Fleet Street becomes the Strand...

until she betrayed him. Sheppard was arrested a third time at Blueskin's mother's brandy shop in Rosemary Lane, east of the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

(later renamed Royal Mint Street), on 23 July by Wild's henchman, Quilt Arnold

Quilt Arnold

Quilt Arnold was one of the chief assistants of 18th century London's master criminal and thief-taker Jonathan Wild. Very little is known about his life and what details we do have come by way of Jonathan Wild himself...

.

Sheppard was imprisoned in Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

pending his trial at the next Assize of oyer and terminer

Oyer and terminer

In English law, Oyer and terminer was the Law French name, meaning "to hear and determine", for one of the commissions by which a judge of assize sat...

. He was prosecuted on three charges of theft at the Old Bailey

Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court in England and Wales, commonly known as the Old Bailey from the street in which it stands, is a court building in central London, one of a number of buildings housing the Crown Court...

, but was acquitted on the first two due to lack of evidence. Kneebone, Wild and Field gave evidence against him on the third charge, the burglary of Kneebone's house. He was convicted on 12 August, the case "being plainly prov'd", and sentenced to death. On Monday 31 August, the very day when the death warrant

Execution warrant

An execution warrant is a writ which authorizes the execution of a judgment of death on an individual...

arrived from the court in Windsor

Windsor, Berkshire

Windsor is an affluent suburban town and unparished area in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is widely known as the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the British Royal Family....

setting Friday 4 September as the date for his execution, Sheppard escaped. Having loosened an iron bar in a window used when talking to visitors, he was visited by Lyon and Poll Maggott, who distracted the guards while he removed the bar. His slight build enabled him to climb through the resulting gap in the grille, and he was smuggled out of Newgate in women's clothing that his visitors had brought him. He took a coach to Blackfriars Stairs, a boat up the River Thames to the horse ferry in Westminster

Westminster

Westminster is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster, England. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames, southwest of the City of London and southwest of Charing Cross...

, near the warehouse where he hid his stolen goods, and made good his escape.

Fourth arrest and final escape

By this point, Sheppard was a working classWorking class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

hero (being a cockney

Cockney

The term Cockney has both geographical and linguistic associations. Geographically and culturally, it often refers to working class Londoners, particularly those in the East End...

, non-violent, and handsome, and seemingly able to escape punishment for his crimes at will). He spent a few days out of London, visiting a friend's family in Chipping Warden

Chipping Warden

Chipping Warden is a village in Northamptonshire, England about northeast of the Oxfordshire town of Banbury. The parish is bounded to the east and south by the River Cherwell, to the west by the boundary with Oxfordshire and to the north by field boundaries....

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire is a landlocked county in the English East Midlands, with a population of 629,676 as at the 2001 census. It has boundaries with the ceremonial counties of Warwickshire to the west, Leicestershire and Rutland to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshire to the south-east,...

, but was soon back in town. He evaded capture by Wild and his men but was arrested again on 9 September by a posse from Newgate as he hid out on Finchley Common

Finchley Common

Finchley Common was an area of land in Middlesex, and until 1816 the boundary between the parishes of Finchley, Friern Barnet and Hornsey.- History :...

, and returned to the condemned cell at Newgate. His fame had increased with each escape, and he was visited in prison by the great, the good and the curious. His plans to escape in September were thwarted twice when the guards found files and other tools in his cell, and he was transferred to a strong-room in Newgate known as the "Castle", clapped in leg irons, and chained to two metal staples in the floor to prevent further escape attempts. After demonstrating to his gaolers that these measures were insufficient, by showing them how he could use a small nail to unlock the horse padlock at will, he was bound more tightly and handcuffed

Handcuffs

Handcuffs are restraint devices designed to secure an individual's wrists close together. They comprise two parts, linked together by a chain, a hinge, or rigid bar. Each half has a rotating arm which engages with a ratchet that prevents it from being opened once closed around a person's wrist...

. In his History, Defoe reports that Sheppard made light of his predicament, joking that "I am the Sheppard, and all the Gaolers in the Town are my Flock, and I cannot stir into the Country, but they are all at my Heels Baughing after me".

Meanwhile, "Blueskin" Blake was arrested by Wild and his men on Friday 9 October, and Tom, Jack's brother, was transported

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

for robbery on Saturday 10 October 1724. New court sessions began on Wednesday 14 October, and Blueskin was tried on Thursday 15 October, with Field and Wild again giving evidence. Their accounts were not consistent with the evidence that they gave at Sheppard's trial, but Blueskin was convicted anyway. Enraged, Blueskin attacked Wild in the courtroom, slashing his throat with a pocket-knife and causing an uproar. Wild was lucky to survive, and his grip over his criminal empire started to slip while he recuperated.

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

prisoners after the Battle of Preston

Battle of Preston (1715)

The Battle of Preston , also referred to as the Preston Fight, was fought during the Jacobite Rising of 1715 ....

. Still wearing his leg irons as night fell, he then broke through six barred doors into the prison chapel, then to the roof of Newgate, 60 feet (20 m) above the ground. He went back down to his cell to get a blanket, then back to the roof of the prison, and used the blanket to reach the roof of an adjacent house, owned by William Bird, a turner. He broke into Bird's house, and went down the stairs and out into the street at around midnight without disturbing the occupants. Escaping through the streets to the north and west, Sheppard hid in a cowshed in Tottenham

Tottenham

Tottenham is an area of the London Borough of Haringey, England, situated north north east of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:Tottenham is believed to have been named after Tota, a farmer, whose hamlet was mentioned in the Domesday Book; hence Tota's hamlet became Tottenham...

(near modern Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road is a major road in central London, United Kingdom, running from St Giles Circus north to Euston Road, near the border of the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, a distance of about three-quarters of a mile...

). Spotted by the barn's owner, Sheppard told him that he had escaped from Bridewell Prison, having been imprisoned there for failing to support a (nonexistent) bastard son. His leg irons remained in place for several days until he persuaded a passing shoemaker to accept the considerable sum of 20 shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s to bring a blacksmith's tools and help him remove them, telling him the same tale. His manacles and leg irons were later recovered in the rooms of Kate Cook, one of Sheppard's mistresses. This escape astonished everyone. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

, working as a journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

, wrote an account for John Applebee, The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard. In his History, Defoe reports the belief in Newgate that the Devil came in person to assist Sheppard's escape.

Final capture

Pawnbroker

A pawnbroker is an individual or business that offers secured loans to people, with items of personal property used as collateral...

's shop in Drury Lane on the night of 29 October 1724, taking a black silk suit, a silver sword, rings, watches, a wig, and other items. He dressed himself as a dandy gentleman and used the proceeds to spend a day and the following evening on the tiles with two mistresses. He was arrested a final time in the early morning on 1 November, blind drunk, "in a handsome Suit of Black, with a Diamond Ring and a Cornelian ring on his Finger, and a fine Light Tye Peruke".

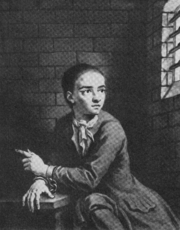

This time, Sheppard was placed in the Middle Stone Room, in the centre of Newgate next to the "Castle", where he could be observed at all times. He was also loaded with three hundred pounds

Pound (mass)

The pound or pound-mass is a unit of mass used in the Imperial, United States customary and other systems of measurement...

of iron weights. He was so celebrated that the gaolers charged high society visitors four shillings to see him, and the King's painter James Thornhill

James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill was an English painter of historical subjects, in the Italian baroque tradition.-Life:...

painted his portrait. Several prominent people sent a petition to King George I

George I of Great Britain

George I was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 until his death, and ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the Holy Roman Empire from 1698....

, begging for his sentence of death to be commuted to transportation

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

. "The Concourse of People of tolerable Fashion to see him was exceeding Great, he was always Chearful and Pleasant to a Degree, as turning almost everything as was said onto a Jest and Banter." To a Reverend Wagstaffe who visited him, he said, according to Defoe, "One file's worth all the Bibles in the World".

Sheppard came before Mr Justice Powis in the Court of King's Bench at Westminster Hall on 10 November. He was offered the chance to have his sentence reduced by informing on his associates, but he scorned the offer, and the death sentence was confirmed. The next day, Blueskin was hanged, and Sheppard was moved to the condemned cell.

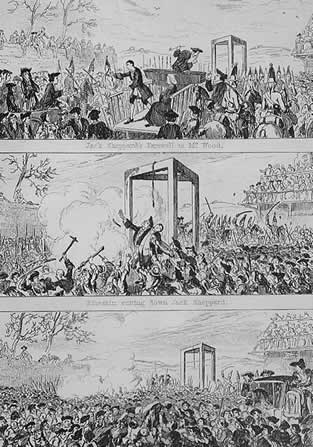

Execution

The following Monday, 16 November, Sheppard was taken to the gallowsGallows

A gallows is a frame, typically wooden, used for execution by hanging, or by means to torture before execution, as was used when being hanged, drawn and quartered...

at Tyburn

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

to be hanged

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

. He planned one more escape, but his pen-knife, intended to cut the ropes binding him on the way to the gallows, was found by a prison warder shortly before he left Newgate for the last time.

A joyous procession passed through the streets of London, with Sheppard's cart drawn along Holborn

Holborn

Holborn is an area of Central London. Holborn is also the name of the area's principal east-west street, running as High Holborn from St Giles's High Street to Gray's Inn Road and then on to Holborn Viaduct...

and Oxford Street

Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major thoroughfare in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, United Kingdom. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, as well as its most dense, and currently has approximately 300 shops. The street was formerly part of the London-Oxford road which began at Newgate,...

accompanied by a mounted City Marshal and liveried

Livery

A livery is a uniform, insignia or symbol adorning, in a non-military context, a person, an object or a vehicle that denotes a relationship between the wearer of the livery and an individual or corporate body. Often, elements of the heraldry relating to the individual or corporate body feature in...

Javelin Men. The occasion was as much as anything a celebration of Sheppard's life, attended by crowds of up to 200,000 (one third of London's population). The procession halted at the City of Oxford tavern on Oxford Street, where Sheppard drank a pint of sack

Sherry

Sherry is a fortified wine made from white grapes that are grown near the town of Jerez , Spain. In Spanish, it is called vino de Jerez....

. A carnival atmosphere pervaded Tyburn, where his "official" autobiography, published by Applebee and probably ghostwritten by Defoe, was on sale. Sheppard handed "a paper to someone as he mounted the scaffold", perhaps as a symbolic endorsement of the account in the "Narrative". His slight build had aided his previous prison escapes, but it condemned him to a slow death by strangulation by the hangman's noose. After hanging for the prescribed 15 minutes, his body was cut down. The crowd pressed forward to stop his body from being removed, fearing dissection

Dissection

Dissection is usually the process of disassembling and observing something to determine its internal structure and as an aid to discerning the functions and relationships of its components....

; their actions inadvertently prevented Sheppard's friends from implementing a plan to take his body to a doctor in an attempt to revive him. His badly mauled remains were recovered later and buried in the churchyard of St Martin's-in-the-Fields that evening.

Legacy

There was a spectacular public reaction to Sheppard's deeds. He was even cited (favourably) as an example in newspapers, pamphlets, broadsheets, and ballads were all devoted to his amazing exploits, and his story was adapted for the stage almost immediately. Harlequin Sheppard, a pantomimePantomime

Pantomime — not to be confused with a mime artist, a theatrical performer of mime—is a musical-comedy theatrical production traditionally found in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Jamaica, South Africa, India, Ireland, Gibraltar and Malta, and is mostly performed during the...

by one John Thurmond (subtitled "A night scene in grotesque characters"), opened at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane is a West End theatre in Covent Garden, in the City of Westminster, a borough of London. The building faces Catherine Street and backs onto Drury Lane. The building standing today is the most recent in a line of four theatres at the same location dating back to 1663,...

on Saturday 28 November, only two weeks after Sheppard's hanging. In a famous contemporary sermon, a London preacher drew on Sheppard's popular escapes as a way of holding his congregation's attention: The account of his life remained well-known through the Newgate Calendar, and a three-act farce was published but never produced, but, mixed with songs, it became The Quaker's Opera, later performed at Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy is a comedy in five acts by Ben Jonson, the last written of his four great comedies. It was first staged on October 31, 1614 at the Hope Theatre by the Lady Elizabeth's Men...

. An imagined dialogue between Jack Sheppard and Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

was published in the British Journal

British Journal

The British Journal was an English newspaper published from 22 September 1722 until 13 January 1728. The paper was then published as the British Journal or The Censor from 20 January 1728 until 23 November 1730 and then as the British Journal or The Traveller from 30 November 1730 until 20 March...

on 4 December 1724, in which Sheppard favourably compares his virtues and exploits to those of Caesar.

Perhaps the most prominent play based on Sheppard's life is John Gay

John Gay

John Gay was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for The Beggar's Opera , set to music by Johann Christoph Pepusch...

's The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera

The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of satirical ballad opera to remain popular today...

(1728). Sheppard was the inspiration for the figure of Macheath; his nemesis, Peachum, is based on Jonathan Wild. The play was spectacularly popular, restoring the fortune that Gay had lost in the South Sea Bubble, and was produced regularly for over 100 years. An unperformed but published play The Prison-Breaker was turned into The Quaker's Opera (in imitation of The Beggar's Opera) and performed at Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy is a comedy in five acts by Ben Jonson, the last written of his four great comedies. It was first staged on October 31, 1614 at the Hope Theatre by the Lady Elizabeth's Men...

in 1725 and 1728. Two centuries later The Beggar's Opera was the basis for The Threepenny Opera

The Threepenny Opera

The Threepenny Opera is a musical by German dramatist Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill, in collaboration with translator Elisabeth Hauptmann and set designer Caspar Neher. It was adapted from an 18th-century English ballad opera, John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, and offers a Marxist critique...

of Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht was a German poet, playwright, and theatre director.An influential theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht made equally significant contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter particularly through the seismic impact of the tours undertaken by the...

and Kurt Weill

Kurt Weill

Kurt Julian Weill was a German-Jewish composer, active from the 1920s, and in his later years in the United States. He was a leading composer for the stage who was best known for his fruitful collaborations with Bertolt Brecht...

(1928).

Sheppard's tale may have been an inspiration for William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

's 1747 series of 12 engraving

Engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on to a hard, usually flat surface, by cutting grooves into it. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an intaglio printing plate, of copper or another metal, for printing...

s, Industry and Idleness

Industry and Idleness

Industry and Idleness is the title of a series of 12 plot-linked engravings created by William Hogarth in 1747, intending to illustrate to working children the possible rewards of hard work and diligent application and the sure disasters attending a lack of both...

, which shows the parallel descent of an apprentice, Tom Idle, into crime and eventually to the gallows, beside the rise of his fellow apprentice, Francis Goodchild, who marries his master's daughter and takes over his business, becoming wealthy as a result, eventually emulating Dick Whittington to become Lord Mayor of London

Lord Mayor of London

The Right Honourable Lord Mayor of London is the legal title for the Mayor of the City of London Corporation. The Lord Mayor of London is to be distinguished from the Mayor of London; the former is an officer only of the City of London, while the Mayor of London is the Mayor of Greater London and...

.

Melodrama

The term melodrama refers to a dramatic work that exaggerates plot and characters in order to appeal to the emotions. It may also refer to the genre which includes such works, or to language, behavior, or events which resemble them...

, Jack Sheppard, The Housebreaker, or London in 1724, by W.T. Moncrieff was published in 1825. More successful was William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth

William Harrison Ainsworth was an English historical novelist born in Manchester. He trained as a lawyer, but the legal profession held no attraction for him. While completing his legal studies in London he met the publisher John Ebers, at that time manager of the King's Theatre, Haymarket...

's third novel, entitled Jack Sheppard, which was originally published in Bentley's Miscellany

Bentley's Miscellany

Bentley's Miscellany was an English literary magazine started by Richard Bentley. It was published between 1836 and 1868.-Contributors:Already a successful publisher of novels, Bentley began the journal in 1836 and invited Charles Dickens to be its first editor...

from January 1839 with illustrations by George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reached an international audience.-Early life:Cruikshank was born in London...

, overlapping with the final episodes of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

' Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress is the second novel by English author Charles Dickens, published by Richard Bentley in 1838. The story is about an orphan Oliver Twist, who endures a miserable existence in a workhouse and then is placed with an undertaker. He escapes and travels to...

. An archetypal Newgate novel

Newgate novel

The Newgate novels were novels published in England from the late 1820s until the 1840s that were thought to glamorise the lives of the criminals they portrayed...

, it generally remains close to the facts of Sheppard's life, but portrays him as a swashbuckling hero. Like Hogarth's prints, the novel pairs the descent of the "idle" apprentice into crime with the rise of a typical melodramatic character, Thames Darrell, a foundling of aristocratic birth who defeats his evil uncle to recover his fortune. Cruikshank's images perfectly complemented Ainsworth's tale—Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray was an English novelist of the 19th century. He was famous for his satirical works, particularly Vanity Fair, a panoramic portrait of English society.-Biography:...

wrote that "...Mr Cruickshank really created the tale, and that Mr Ainsworth, as it were, only put words to it." The novel quickly became very popular: it was published in book form later that year, before the serialised version was completed, and even outsold early editions of Oliver Twist. Ainsworth's novel was adapted into a successful play by John Buckstone in October 1839 at the Adelphi Theatre

Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a 1500-seat West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiving house for a variety of productions, including many musicals...

starring (strangely enough) Mary Anne Keeley

Mary Anne Keeley

Mary Anne Keeley, née Goward was an English actress and actor-manager.She was born at Ipswich, her father being a brazier and tinman. After some experience in the provinces, she first appeared on the stage in London on July 2, 1825, in the opera Rosina...

; indeed, it seems likely that Cruikshank's illustrations were deliberately created in a form that were informed by, and would be easy to repeat as, tableaux

Tableau vivant

Tableau vivant is French for "living picture." The term describes a striking group of suitably costumed actors or artist's models, carefully posed and often theatrically lit. Throughout the duration of the display, the people shown do not speak or move...

on stage. It has been described as the "exemplary climax" of "the pictorial novel dramatized pictorially".

The story generated a form of cultural mania, embellished by pamphlets, prints, cartoons, plays and souvenirs, not repeated until George du Maurier

George du Maurier

George Louis Palmella Busson du Maurier was a French-born British cartoonist and author, known for his cartoons in Punch and also for his novel Trilby. He was the father of actor Gerald du Maurier and grandfather of the writers Angela du Maurier and Dame Daphne du Maurier...

's Trilby

Trilby (novel)

Trilby is a novel by George du Maurier and one of the most popular novels of its time, perhaps the second best selling novel of the Fin de siècle after Bram Stoker's Dracula. Published serially in Harper's Monthly in 1894, it was published in book form in 1895 and sold 200,000 copies in the United...

in 1895. By early 1840, a cant

Thieves' cant

Thieves' cant or Rogues' cant was a secret language which was formerly used by thieves, beggars and hustlers of various kinds in Great Britain and to a lesser extent in other English-speaking countries...

song from Buckstone's play, "Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away" was reported to be "deafening us in the streets". Public alarm at the possibility that young people would emulate Sheppard's behaviour led the Lord Chamberlain

Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain or Lord Chamberlain of the Household is one of the chief officers of the Royal Household in the United Kingdom and is to be distinguished from the Lord Great Chamberlain, one of the Great Officers of State....

to ban, at least in London, the licensing

Licensing Act 1737

The Licensing Act or Theatrical Licensing Act of 21 June 1737 was a landmark act of censorship of the British stage and one of the most determining factors in the development of Augustan drama...

of any plays with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years. The fear may not have been entirely unfounded: Courvousier, the valet of Lord William Russell

Lord William Russell (aristocrat)

Lord William Russell , a member of the British aristocratic family of Russell and longtime Member of Parliament, did little to attract public attention after the end of his political career until, in 1840, he was murdered in his sleep by his valet.-Life:Russell was the posthumous child of Francis...

, claimed in one of his several confessions that the book had inspired him to murder his master. Frank

Frank James

Alexander Franklin "Frank" James was a famous American outlaw. He was the older brother of outlaw Jesse James.-Childhood:...

and Jesse James

Jesse James

Jesse Woodson James was an American outlaw, gang leader, bank robber, train robber, and murderer from the state of Missouri and the most famous member of the James-Younger Gang. He also faked his own death and was known as J.M James. Already a celebrity when he was alive, he became a legendary...

wrote letters to the Kansas City Star signed "Jack Sheppard". Nevertheless, a number of burlesques of the story were written after the ban was lifted, including a popular Gaiety Theatre, London

Gaiety Theatre, London

The Gaiety Theatre, London was a West End theatre in London, located on Aldwych at the eastern end of the Strand. The theatre was established as the Strand Musick Hall , in 1864 on the former site of the Lyceum Theatre. It was rebuilt several times, but closed from the beginning of World War II...

piece called Little Jack Sheppard

Little Jack Sheppard

Little Jack Sheppard is a burlesque melodrama written by Henry Pottinger Stephens and William Yardley, with music by Meyer Lutz, with songs contributed by Florian Pascal, Corney Grain, Arthur Cecil, Michael Watson, Henry J. Leslie, Alfred Cellier and Hamilton Clarke...

(1885-86) by Henry Pottinger Stephens

Henry Pottinger Stephens

Henry Pottinger Stephens, also known as Henry Beauchamp , was an English dramatist and journalist. With a variety of partners, he wrote burlesques, comic operas and musical comedies that briefly rivalled the Savoy Operas in popular esteem.-Life and career:"Pot" Stephens was born in Barrow-on-Soar,...

and W. Yardley, with music by Meyer Lutz

Meyer Lutz

Wilhelm Meyer Lutz was a German-born English composer and conductor who is best known for light music, musical theatre and burlesques of well-known works....

and others.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1056120

The Sheppard story has been revived several times in the 20th century, including three silent movie

Silent Movie

Silent Movie is a 1976 satirical comedy film co-written, directed by, and starring Mel Brooks, and released by 20th Century Fox on June 17, 1976...

s, The Hairbreadth Escape of Jack Sheppard (1900), Robbery of the Mail Coach (1903) and Jack Sheppard (1923); a book, The Road to Tyburn, by Christopher Hibbert

Christopher Hibbert

Christopher Hibbert, MC, FRSL, FRGS was an English writer, historian and biographer. He has been called "a pearl of biographers" and "probably the most widely-read popular historian of our time and undoubtedly one of the most prolific"...

(1957); a British costume drama, Where's Jack?

Where's Jack?

Where's Jack? is a 1969 film based around the exploits of notorious 18th century criminal Jack Sheppard and London "thieftaker" Jonathan Wild....

, directed by James Clavell

James Clavell

James Clavell, born Charles Edmund DuMaresq Clavell was an Australian-born, British novelist, screenwriter, director and World War II veteran and prisoner of war...

, with Tommy Steele

Tommy Steele

Tommy Steele OBE , is an English entertainer. Steele is widely regarded as Britain's first teen idol and rock and roll star.-Singer:...

in the title role (1969); an unrealised film project of FilmFour Productions in 2000, Jack Sheppard and Jonathan Wild, for which Benjamin Ross, who would have been director, co-wrote the screenplay

Screenplay

A screenplay or script is a written work that is made especially for a film or television program. Screenplays can be original works or adaptations from existing pieces of writing. In them, the movement, actions, expression, and dialogues of the characters are also narrated...

with John Preston, with Tobey Maguire

Tobey Maguire

Tobias Vincent "Tobey" Maguire is an American actor and producer. He began his career in the 1980s, and has achieved his greatest fame for his role as Peter Parker/Spider-Man in Sam Raimi's Spider-Man films.-Early life:...

and Harvey Keitel

Harvey Keitel

Harvey Keitel is an American actor. Some of his most notable starring roles were in Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, Ridley Scott's The Duellists and Thelma and Louise, Ettore Scola's That Night in Varennes, Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, Jane Campion's The...

slated for the main parts; a 2002 television drama, Invitation to a Hanging; and a series of novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

s by Neal Stephenson

Neal Stephenson

Neal Town Stephenson is an American writer known for his works of speculative fiction.Difficult to categorize, his novels have been variously referred to as science fiction, historical fiction, cyberpunk, and postcyberpunk...

collectively known as, The Baroque Cycle

The Baroque Cycle

The Baroque Cycle is a series of novels by American writer Neal Stephenson. It was published in three volumes containing 8 books in 2003 and 2004. The story follows the adventures of a sizeable cast of characters living amidst some of the central events of the late 17th and early 18th centuries in...

(2003, 2004), in which the character Jack Shaftoe

Jack Shaftoe

Jack Shaftoe is one of the three primary fictional characters in Neal Stephenson's 2,686-page, Clarke Award-winning epic trilogy, The Baroque Cycle.Born in 1660 to a poor London...

was partly inspired by events from the life of Jack Sheppard.

Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker

Abraham "Bram" Stoker was an Irish novelist and short story writer, best known today for his 1897 Gothic novel Dracula...

references Jack Sheppard in "Dracula

Dracula

Dracula is an 1897 novel by Irish author Bram Stoker.Famous for introducing the character of the vampire Count Dracula, the novel tells the story of Dracula's attempt to relocate from Transylvania to England, and the battle between Dracula and a small group of men and women led by Professor...

" when referring to the patient, Renfield.

The reasons for the lasting legacy of Jack Sheppard's exploits in the popular imagination have been addressed by Peter Linebaugh, who suggests that Sheppard's legend was rooted in the prospect of excarceration, of escape from what Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault , born Paul-Michel Foucault , was a French philosopher, social theorist and historian of ideas...

in Folie et déraison

Madness and Civilization

Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason by Michel Foucault, is the English edition of Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, a 1964 abridged edition of the 1961 Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique. An English translation of the complete 1961...

called the grand renfermement (Great Confinement), in which "unreasonable" members of the population were locked away and institutionalised. The laws levelled at Sheppard and similar working class criminals were a means of disciplining a potentially rebellious multitude into accepting increasingly harsh property laws. A nineteenth-century view on the Jack Sheppard phenomenon was offered by Charles Mackay

Charles Mackay

Charles Mackay was a Scottish poet, journalist, and song writer.-Life:Charles Mackay was born in Perth, Scotland. His father was by turns a naval officer and a foot soldier; his mother died shortly after his birth. Charles was educated at the Caledonian Asylum, London, and at Brussels, but spent...

in Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is a history of popular folly by Scottish journalist Charles Mackay, first published in 1841. The book chronicles its subjects in three parts: "National Delusions", "Peculiar Follies", and "Philosophical Delusions"...

:

Further reading

- Anon (often attributed to Defoe). A Narrative of All the Robberies, Escapes, Etc. of John Sheppard. 1724.

- Bleackley, Horace. Trial of Jack Sheppard. Wm Gaunt & Sons, (1933) 1996 edition. ISBN 1-56169-117-8.

- G.E. Authentick Memoirs of the Life and Surprising Adventures of John Sheppard by Way of Familiar Letters from a Gentleman in Town. 1724.

- Gatrell, V.A. The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770–1868. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-285332-5.

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Road to Tyburn: The story of Jack Sheppard and the Eighteenth-Century London Underworld. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1957. (2001 Penguin reprint: ISBN 0-14-139023-9)

- Linnane, Fergus. The Encyclopedia of London Crime. Sutton Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7509-3302-X.

- Meisel, Martin. (1983) Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton.

- Rawlings, Philip. Drunks, Whores, and Idle Apprentices: Criminal Biographies of the Eighteenth Century. Routledge (UK), 1992. ISBN 0-415-05056-1.

- Rogers, Pat. Daniel Defoe: The Critical Heritage. Routledge (UK), 1995. ISBN 0-415-13423-4.

External links

- Jack Sheppard, from the Newgate Calendar, including contemporary sermon. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- The Lure of the Scoundrel, from Rare Book Review. Retrieved 5 February 2007.