Tyburn, London

Encyclopedia

|

|

|

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

close to the current location of Marble Arch

Marble Arch

Marble Arch is a white Carrara marble monument that now stands on a large traffic island at the junction of Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Edgware Road, almost directly opposite Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park in London, England...

in present-day London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream'

Tyburn (stream)

The Tyburn is a stream in London, which runs underground from South Hampstead through St. James's Park to meet the River Thames at Pimlico near Vauxhall Bridge. It is not to be confused with the Tyburn Brook which is a tributary of the River Westbourne....

, a tributary of the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the Thames.

The name was almost universally used in literature to refer to the notorious and uniquely designed gallows, used for centuries as the primary location of the execution of London criminals.

History

The village was one of two manorManorialism

Manorialism, an essential element of feudal society, was the organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire, was widely practiced in medieval western and parts of central Europe, and was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market...

s of the parish

Parish

A parish is a territorial unit historically under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of one parish priest, who might be assisted in his pastoral duties by a curate or curates - also priests but not the parish priest - from a more or less central parish church with its associated organization...

of Marylebone

Marylebone

Marylebone is an affluent inner-city area of central London, located within the City of Westminster. It is sometimes written as St. Marylebone or Mary-le-bone....

, which was itself named after the stream, St Marylebone being a contraction of St Mary's church by the bourne. Tyburn was recorded in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

and stood approximately at the west end of what is now Oxford Street

Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major thoroughfare in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, United Kingdom. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, as well as its most dense, and currently has approximately 300 shops. The street was formerly part of the London-Oxford road which began at Newgate,...

at the junction of two Roman road

Roman road

The Roman roads were a vital part of the development of the Roman state, from about 500 BC through the expansion during the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. Roman roads enabled the Romans to move armies and trade goods and to communicate. The Roman road system spanned more than 400,000 km...

s. The predecessors of Oxford Street and Park Lane

Park Lane (road)

Park Lane is a major road in the City of Westminster, in Central London.-History:Originally a country lane running north-south along what is now the eastern boundary of Hyde Park, it became a fashionable residential address from the eighteenth century onwards, offering both views across Hyde Park...

were roads leading to the village, then called Tyburn Road and Tyburn Lane respectively.

In the 1230s and 1240s the village of Tyburn was held by Gilbert de Sandford, the son of John de Sandford who had been the Chamberlain of Queen Eleanor. Eleanor had been the wife of King Henry II who encouraged her sons Henry and Richard to rebel against her husband, King Henry. In 1236 the city of London contracted with Sir Gilbert to draw water from Tyburn Springs, which he held, to serve as the source of the first piped water supply for the city. The water was supplied in lead pipes that ran from where Bond Street Station stands today, half a mile east of Hyde Park, down to the hamlet of Charing (Charing Cross), along Fleet Street and over the Fleet Bridge, climbing Ludgate Hill (by gravitational pressure) to a public conduit at Cheapside. Water was supplied for free to all comers.

Tyburn had significance from ancient times and was marked by a monument known as Oswulf's Stone, which gave its name to the Ossulstone

Ossulstone

Ossulstone was an ancient hundred in the south east of the county of Middlesex, England. Its area has been entirely absorbed by the growth of London; and now corresponds to the part of Inner London that is north of the River Thames and, from Outer London, parts of the London boroughs of Barnet,...

Hundred

Hundred (division)

A hundred is a geographic division formerly used in England, Wales, Denmark, South Australia, some parts of the United States, Germany , Sweden, Finland and Norway, which historically was used to divide a larger region into smaller administrative divisions...

of Middlesex

Middlesex

Middlesex is one of the historic counties of England and the second smallest by area. The low-lying county contained the wealthy and politically independent City of London on its southern boundary and was dominated by it from a very early time...

. The stone was covered over in 1851 when Marble Arch

Marble Arch

Marble Arch is a white Carrara marble monument that now stands on a large traffic island at the junction of Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Edgware Road, almost directly opposite Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park in London, England...

was moved to the area, but it was shortly afterwards unearthed and propped up against the Arch. It has not been seen since 1869.

Tyburn gallows

Executions took place at Tyburn until the late 18th century (with the prisoners processed from Newgate PrisonNewgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

in the City

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

, via St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields, Holborn, is a church in the London Borough of Camden, in the West End. It is close to the Centre Point office tower and the Tottenham Court Road tube station. The church is part of the Diocese of London within the Church of England...

and Oxford Street

Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major thoroughfare in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, United Kingdom. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, as well as its most dense, and currently has approximately 300 shops. The street was formerly part of the London-Oxford road which began at Newgate,...

), after which they were carried out at Newgate itself and at Horsemonger Lane Gaol

Horsemonger Lane Gaol

Horsemonger Lane Gaol was a prison close to present-day Newington Causeway in Southwark, south London.-History:...

in Southwark

Southwark

Southwark is a district of south London, England, and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Southwark. Situated east of Charing Cross, it forms one of the oldest parts of London and fronts the River Thames to the north...

.

The first recorded execution took place at a site next to the stream in 1196. William Fitz Osbern

William Fitz Osbern (1196)

William Fitz Osbert or William with the long beard was a citizen of London who took up the role of the advocate of the poor in a popular uprising in the spring of 1196. The events are significant in that they illustrate how rare popular revolt by the poor and peasants in England was in the 12th...

, the populist leader of the poor of London was cornered in the church of St Mary le Bow. He was dragged naked behind a horse to Tyburn, where he was hanged. In 1537, Henry VIII used Tyburn to execute the ringleaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace

Pilgrimage of Grace

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular rising in York, Yorkshire during 1536, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances. It was done in action against Thomas Cromwell...

, including Nicholas Tempest, one of the northern leaders of the Pilgrimage and the King's own Bowbearer of the Forest of Bowland

Forest of Bowland

The Forest of Bowland, also known as the Bowland Fells, is an area of barren gritstone fells, deep valleys and peat moorland, mostly in north-east Lancashire, England. A small part lies in North Yorkshire, and much of the area was historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire...

.

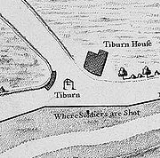

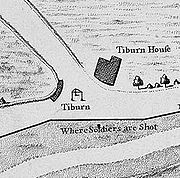

In 1571, the "Tyburn Tree" was erected near the modern Marble Arch

Marble Arch

Marble Arch is a white Carrara marble monument that now stands on a large traffic island at the junction of Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Edgware Road, almost directly opposite Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park in London, England...

. The "Tree" or "Triple Tree" was a novel form of gallows

Gallows

A gallows is a frame, typically wooden, used for execution by hanging, or by means to torture before execution, as was used when being hanged, drawn and quartered...

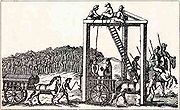

, comprising a horizontal wooden triangle supported by three legs (an arrangement known as a "three-legged mare" or "three-legged stool"). Several felons could thus be hanged at once, and so the gallows were used for mass executions, such as on 23 June 1649 when 24 prisoners – 23 men and one woman – were hanged simultaneously, having been conveyed there in eight carts.

The Tree stood in the middle of the roadway, providing a major landmark in west London and presenting a very obvious symbol of the law to travellers. After executions, the bodies would be buried nearby or in later times removed for dissection

Dissection

Dissection is usually the process of disassembling and observing something to determine its internal structure and as an aid to discerning the functions and relationships of its components....

by anatomists

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

.

The first victim of the "Tyburn Tree" was Dr John Story

John Story

Blessed John Story , English Roman Catholic martyr, was born the son of Nicholas Story of Salisbury and educated at Hinxsey Hall, University of Oxford, where he became lecturer on civil law in 1535, being made later principal of Broadgates Hall, afterwards Pembroke College.He appears to have...

, a Roman Catholic who refused to recognize Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

. Among the more notable individuals suspended from the "Tree" in the following centuries were John Bradshaw

John Bradshaw (judge)

John Bradshaw was an English judge. He is most notable for his role as President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I and as the first Lord President of the Council of State of the English Commonwealth....

, Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton was an English general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War. He was the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell.-Early life:...

and Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

, who were already dead but were disinterred and hanged at Tyburn in January 1661 on the orders of Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

in an act of posthumous revenge for their part in the beheading of his father.

The executions were public spectacles and proved extremely popular, attracting crowds of thousands. The enterprising villagers of Tyburn erected large spectator stands so that as many as possible could see the hangings (for a fee). On one occasion, the stands collapsed, reportedly killing and injuring hundreds of people. This did not prove a deterrent, however, and the executions continued to be treated as public holidays, with London apprentices being given the day off for them. One such event was depicted by William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

in his satirical print, The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn (1747).

Tyburn was commonly invoked in euphemism

Euphemism

A euphemism is the substitution of a mild, inoffensive, relatively uncontroversial phrase for another more frank expression that might offend or otherwise suggest something unpleasant to the audience...

s for capital punishment – for instance, to "take a ride to Tyburn" (or simply "go west") was to go to one's hanging, "Lord of the Manor of Tyburn" was the public hangman, "dancing the Tyburn jig" was the act of being hanged, and so on. Convicts would be transported to the site in an open ox-cart from Newgate Prison. They were expected to put on a good show, wearing their finest clothes and going to their deaths with insouciance. The crowd would cheer a "good dying", but would jeer any displays of weakness on the part of the condemned.

On 19 April 1779, clergyman James Hackman

James Hackman

James Hackman , briefly Rector of Wiveton in Norfolk, was the murderer who killed Martha Ray, singer and mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.-Early life:...

was hanged there following his 7 April murder of courtesan

Courtesan

A courtesan was originally a female courtier, which means a person who attends the court of a monarch or other powerful person.In feudal society, the court was the centre of government as well as the residence of the monarch, and social and political life were often completely mixed together...

and socialite

Socialite

A socialite is a person who participates in social activities and spends a significant amount of time entertaining and being entertained at fashionable upper-class events....

Martha Ray

Martha Ray

Martha Ray was a British singer of the Georgian era. Her father was a corsetmaker and her mother was a servant in a noble household. Good-looking, intelligent, and a talented singer, she came to the attention of many of her father's patrons. She is best known for her affair with John Montagu, 4th...

, his former lover, and the mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, PC, FRS was a British statesman who succeeded his grandfather, Edward Montagu, 3rd Earl of Sandwich, as the Earl of Sandwich in 1729, at the age of ten...

. The Tyburn gallows were last used on 3 November 1783, when John Austin

John Austin (highwayman)

John Austin the highwayman has the distinction of being the last man hanged at Tyburn Tree in Tyburn, a village in the county of Middlesex, before the gallows were disassembled....

, a highwayman

Highwayman

A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads...

, was hanged. The site of the gallows is now marked by three brass triangles mounted on the pavement on an island in the middle of Edgware Road at its junction with Bayswater Road. It is also commemorated by the Tyburn Convent, a Catholic convent dedicated to the memory of martyrs executed there and in other locations for the Catholic faith.

Tyburn today remains the point at which Watling Street

Watling Street

Watling Street is the name given to an ancient trackway in England and Wales that was first used by the Britons mainly between the modern cities of Canterbury and St Albans. The Romans later paved the route, part of which is identified on the Antonine Itinerary as Iter III: "Item a Londinio ad...

, the modern A5 begins. It continues in straight sections to Holyhead

Holyhead

Holyhead is the largest town in the county of Anglesey in the North Wales. It is also a major port adjacent to the Irish Sea serving Ireland....

. According to an 1850 publication, the site was at No. 49. Connaught Square

Connaught Square

Connaught Square, in the City of Westminster , was the first square of city houses to be built in the Bayswater area. It was named after the Duke of Gloucester , who had a house nearby. The current appearance of the square dates from the 1820s. The square is just north of Hyde Park, and to the west...

.

Some notable executions at Tyburn (in chronological order)

| Name | | Date | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March |

29 November 1330 | Accused of assuming royal power; hanged without trial. |

| Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton | 8 July 1486 | Accused of siding with Richard III Richard III of England Richard III was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty... ; hanged without trial on orders of Henry VII Henry VII of England Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor.... . |

| Michael An Gof Michael An Gof Michael Joseph and Thomas Flamank were the leaders of the Cornish Rebellion of 1497.... & Thomas Flamank Thomas Flamank Thomas Flamank was a lawyer from Cornwall who together with Michael An Gof led the Cornish Rebellion against taxes in 1497.... |

27 June 1497 | Leaders of the 1st Cornish Rebellion of 1497 Cornish Rebellion of 1497 The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a popular uprising by the people of Cornwall in the far southwest of Britain. Its primary cause was a response of people to the raising of war taxes by King Henry VII on the impoverished Cornish, to raise money for a campaign against Scotland motivated by brief... . |

| Perkin Warbeck Perkin Warbeck Perkin Warbeck was a pretender to the English throne during the reign of King Henry VII of England. By claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger son of King Edward IV, one of the Princes in the Tower, Warbeck was a significant threat to the newly established Tudor Dynasty,... |

23 November 1499 | Treason Treason In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a... ; pretender Pretender A pretender is one who claims entitlement to an unavailable position of honour or rank. Most often it refers to a former monarch, or descendant thereof, whose throne is occupied or claimed by a rival, or has been abolished.... to the throne of Henry VII of England by passing himself off as Richard IV, the younger of the two Princes in the Tower Princes in the Tower The Princes in the Tower is a term which refers to Edward V of England and Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York. The two brothers were the only sons of Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville alive at the time of their father's death... . Leader of the 2nd Cornish Rebellion of 1497 Cornish Rebellion of 1497 The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a popular uprising by the people of Cornwall in the far southwest of Britain. Its primary cause was a response of people to the raising of war taxes by King Henry VII on the impoverished Cornish, to raise money for a campaign against Scotland motivated by brief... . |

| Elizabeth Barton Elizabeth Barton Sr. Elizabeth Barton was an English Catholic nun... "The Holy Maid of Kent" |

20 April 1534 | Treason Treason In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a... ; a nun who unwisely prophesied that King Henry VIII Henry VIII of England Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France... would die within six months if he married Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn ;c.1501/1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536 as the second wife of Henry VIII of England and Marquess of Pembroke in her own right. Henry's marriage to Anne, and her subsequent execution, made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that was the... . |

| John Houghton Saint John Houghton Saint John Houghton, O.Cart., was a Carthusian hermit and Catholic priest and the first English Catholic martyr to die as a result of the Act of Supremacy by King Henry VIII of England... |

4 May 1535 | Prior Prior Prior is an ecclesiastical title, derived from the Latin adjective for 'earlier, first', with several notable uses.-Monastic superiors:A Prior is a monastic superior, usually lower in rank than an Abbot. In the Rule of St... of the Charterhouse London Charterhouse The London Charterhouse is a historic complex of buildings in Smithfield, London dating back to the 14th century. It occupies land to the north of Charterhouse Square. The Charterhouse began as a Carthusian priory, founded in 1371 and dissolved in 1537... who refused to swear the oath condoning King Henry VIII Henry VIII of England Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France... 's divorce of Catherine of Aragon Catherine of Aragon Catherine of Aragon , also known as Katherine or Katharine, was Queen consort of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII of England and Princess of Wales as the wife to Arthur, Prince of Wales... . |

| Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare , also known as Silken Thomas , was a figure in Irish history.He spent a considerable part of his early life in England: his mother Elizabeth Zouche, was a cousin of Henry VII... |

3 Feb 1537 | Rebel, renounced his allegiance to Henry VIII. At length, on the 3rd of February, 1537, the Earl, after imprisonment of sixteen months, and five of his uncles, of eleven months, were executed as traitors at Tyburn, being drawn, hung and quartered. The Irish Government, not satisfied with the arrest of the Earl alone wrote to Cromwell and was determined that the five uncles (James, Oliver, Richard, John and Walter) should be arrested also. ref. The Earls of Kildare and their Ancestors. By the Marquis of Kildare. Third addition 1858. The sole male representative to the Kildare Geraldines was then smuggled to safety by his tutor at the age of twelve. Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare , also known as the "Wizard Earl" , was an Irish peer.... (1525–1585), also known as the "Wizard Earl". |

| Thomas Fiennes, 9th Baron Dacre Thomas Fiennes, 9th Baron Dacre Thomas Fiennes, 9th Baron Dacre was an English aristocrat notable for his conviction and execution for murder.Dacre was the son of Sir Thomas Fiennes and Jane Sutton daughter of Edward Sutton, 2nd Baron Dudley... |

29 June 1541 | Lord Dacre was convicted of murder after being involved in the death of a gamekeeper whilst taking part in a poaching expedition on the lands of Sir Nicholas Pelham of Laughton Laughton, East Sussex Laughton is a village and civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. The village is located five miles east of Lewes, at a junction on the minor road to Hailsham . It appears in the Domesday Book, and there are Roman remains nearby.Education is provided at the Laughton Community... . |

| Francis Dereham Francis Dereham Francis Dereham was a Tudor courtier whose involvement with Henry VIII's fifth Queen, Catherine Howard, in her youth was a principal cause of the Queen's execution.-Life:... |

10 December 1541 | A courtier of King Henry VIII Henry VIII of England Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France... who had an affair with his fifth wife, Queen Catherine Howard Catherine Howard Catherine Howard , also spelled Katherine, Katheryn or Kathryn, was the fifth wife of Henry VIII of England, and sometimes known by his reference to her as his "rose without a thorn".... . Unusually, Culpeper was beheaded, a death normally reserved for the nobility, carried out at Tower Hill Tower Hill Tower Hill is an elevated spot northwest of the Tower of London, just outside the limits of the City of London, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Formerly it was part of the Tower Liberty under the direct administrative control of Tower... . Culpeper and Francis Dereham Francis Dereham Francis Dereham was a Tudor courtier whose involvement with Henry VIII's fifth Queen, Catherine Howard, in her youth was a principal cause of the Queen's execution.-Life:... were both sentenced to be 'hanged, drawn and quartered Hanged, drawn and quartered To be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I... ' but Henry ordered that Culpeper's sentence be commuted to beheading on account of his previously good relationship with Henry. The unfortunate Dereham suffered the full sentence. |

| William Leech of Fulletby Fulletby Fulletby is a village and a civil parish in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It lies in the Lincolnshire Wolds, northeast of Horncastle, south of Louth and northwest of Spilsby. The parish covers about .- History :... |

8 May 1543 | A ringleader of the rebellion called the Pilgrimage of Grace Pilgrimage of Grace The Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular rising in York, Yorkshire during 1536, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances. It was done in action against Thomas Cromwell... in 1536, Leech escaped to Scotland. He murdered the Somerset Herald Somerset Herald Somerset Herald of Arms in Ordinary is an officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. In the year 1448 Somerset Herald is known to have served the Duke of Somerset, but by the time of the coronation of King Henry VII in 1485 his successor appears to have been raised to the rank of a royal... , Thomas Trahern Thomas Trahern (officer of arms) Thomas Trahern was Somerset Herald, an English officer of arms. His murder was a setback to Anglo-Scottish relations.-Prelude:... , at Dunbar Dunbar Dunbar is a town in East Lothian on the southeast coast of Scotland, approximately 28 miles east of Edinburgh and 28 miles from the English Border at Berwick-upon-Tweed.... on 25 November 1542, causing an international incident, and was delivered for hanging in London. |

| Humphrey Arundell Humphrey Arundell Sir Humphrey Arundell was the leader of Cornish forces in the Prayer Book Rebellion early in the reign of King Edward VI. He was executed at Tyburn, London after the rebellion had been defeated.-Life:... |

27 January 1550 | Leader of the Cornish Rebellion against the English in 1549 - sometimes known as the Prayer Book Rebellion Prayer Book Rebellion The Prayer Book Rebellion, Prayer Book Revolt, Prayer Book Rising, Western Rising or Western Rebellion was a popular revolt in Cornwall and Devon, in 1549. In 1549 the Book of Common Prayer, presenting the theology of the English Reformation, was introduced... |

| Edmund Campion Edmund Campion Saint Edmund Campion, S.J. was an English Roman Catholic martyr and Jesuit priest. While conducting an underground ministry in officially Protestant England, Campion was arrested by priest hunters. Convicted of high treason by a kangaroo court, he was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn... |

1 December 1581 | Roman Catholic priest Priest A priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities... s. |

| John Adams John Adams (martyr) John Adams was a Catholic priest and martyr.He was born at Winterborne St Martin in Dorset at an unknown date and became a Protestant minister. He later entered the Catholic Church and travelled to the English College then at Rheims, arriving on December 7, 1579. He was ordained a priest at... |

8 October 1586 | |

| Robert Dibdale Robert Dibdale Robert Dibdale, or Debdale, was a Catholic priest and martyr.He was born the son of John Dibdale of Shottery, in the parish of Stratford-upon-Avon and the birthplace of William Shakespeare's wife Anne Hathaway at a date unknown. He had a brother Richard and sisters Joan and Agnes. It would seem... |

||

| John Lowe | ||

| Robert Southwell | 21 February 1595 | |

| Philip Powel | 30 June 1646 | |

| Peter Wright Peter Wright (martyr) Blessed Peter Wright was a Catholic priest, Jesuit, and martyr, born in Slipton, Northamptonshire, England.-Biography:In older literature he was presumed to be a Protestant, but more recently record of him has been found at Slipton in 1613 as a Recusant, along with his mother, brother and sister... |

19 May 1651 | |

| John Southworth | 28 June 1654 | |

| Oliver Cromwell Oliver Cromwell Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland.... |

30 January 1661 | posthumous execution Posthumous execution Posthumous execution is the ritual or ceremonial mutilation of an already dead body as a punishment.-Examples:* Li Linfu, Chancellor of Tang China during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong in the latter years, was exhumed and executed for crimes of high treason by his rival Yang Guozhong for his... following exhumation of his body from Westminster Abbey Westminster Abbey The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,... . |

| Robert Hubert Robert Hubert Robert Hubert was a watchmaker from Rouen, France, who was executed following his false confession of starting the Great Fire of London.-Great Fire of London:... |

28 September 1666 | Falsely confessed to starting the Great Fire of London Great Fire of London The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the central parts of the English city of London, from Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall... . |

| Claude Duval Claude Duval For other uses, see Claude Duval Claude Du Vall was a French-born gentleman highwayman in post-Restoration Britain.-Early life:... |

21 January 1670 | Highwayman Highwayman A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads... . |

| Saint Oliver Plunkett Oliver Plunkett Saint Oliver Plunkett was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.... |

1 July 1681 | Archbishop of Armagh, Primate of All Ireland and martyr Martyr A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:... . |

| Jane Voss | 19 December 1684 | Robbing on the highway, high treason, murder, and felony |

| William Chaloner William Chaloner William Chaloner was a serial offender counterfeit coiner and confidence trickster, who was imprisoned in Newgate Prison several times and eventually proven guilty of High Treason by Sir Isaac Newton, Master of the Royal Mint... |

23 March 1699 | Notorious coiner and counterfeiter, convicted of high treason partly on evidence gathered by Isaac Newton Isaac Newton Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."... |

| Jack Hall Jack Hall (song) -Story:Jack Hall was a criminal who, as a young boy, was sold to a chimney sweep for a guinea. In later life he became a notorious highwayman. In 1707 he was arrested along with Stephen Bunce and Dick Low for a burglary committed at the house of Captain Guyon, near Stepney. All three were convicted... |

1707 | A chimney-sweep, hanged for committing a burglary. There is a folk-song about him, which bears his name (and another song with the variant name of Sam Hall Sam Hall (song) “Sam Hall” is an old English folk song about a bitterly unrepentant criminal condemned to death . Prior to the mid 19th century it was called “Jack Hall”, after an infamous English thief, who was hanged in 1707 at Tyburn... ). |

| Jack Sheppard Jack Sheppard Jack Sheppard was a notorious English robber, burglar and thief of early 18th-century London. Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter but took to theft and burglary in 1723, with little more than a year of his training to complete... "Gentleman Jack" |

16 November 1724 | Notorious thief and multiple escapee. |

| Jonathan Wild Jonathan Wild Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them... |

24 May 1725 | Organized crime Organized crime Organized crime or criminal organizations are transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals for the purpose of engaging in illegal activity, most commonly for monetary profit. Some criminal organizations, such as terrorist organizations, are... lord. |

| James MacLaine James MacLaine "Captain" James MacLaine was a notorious highwayman with his accomplice William Plunkett. He was known as the "Gentleman Highwayman" as a result of his courteous behaviour during his robberies. He famously robbed Horace Walpole, and was eventually hanged at Tyburn... "The Gentleman Highwayman" |

3 October 1750 | Highwayman Highwayman A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads... . |

| Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers was the last member of the House of Lords hanged in England.The 4th Earl Ferrers, descendant of an ancient and noble family, was the eldest son of Hon. Laurence Ferrers, himself a younger son of the Robert Shirley, 1st Earl Ferrers-a descendant of Robert... |

5 May 1760 | The last peer to be hanged for murder. |

| John Rann John Rann John "Sixteen String Jack" Rann was an English criminal and highwayman during the mid-18th century. He was a prominent and colourful local figure renowned for his wit and charm, he would later come to be known as "Sixteen String Jack" for the 16 various coloured strings he wore on the knees of his... "Sixteen String Jack" |

30 November 1774 | Highwayman Highwayman A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads... |

| Rev. James Hackman James Hackman James Hackman , briefly Rector of Wiveton in Norfolk, was the murderer who killed Martha Ray, singer and mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.-Early life:... |

19 April 1779 | Hanged for the murder of Martha Ray Martha Ray Martha Ray was a British singer of the Georgian era. Her father was a corsetmaker and her mother was a servant in a noble household. Good-looking, intelligent, and a talented singer, she came to the attention of many of her father's patrons. She is best known for her affair with John Montagu, 4th... , mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, PC, FRS was a British statesman who succeeded his grandfather, Edward Montagu, 3rd Earl of Sandwich, as the Earl of Sandwich in 1729, at the age of ten... . |

| John Austin John Austin (highwayman) John Austin the highwayman has the distinction of being the last man hanged at Tyburn Tree in Tyburn, a village in the county of Middlesex, before the gallows were disassembled.... |

3 November 1783 | A highwayman Highwayman A highwayman was a thief and brigand who preyed on travellers. This type of outlaw, usually, travelled and robbed by horse, as compared to a footpad who traveled and robbed on foot. Mounted robbers were widely considered to be socially superior to footpads... , the last person to be executed at Tyburn. |

See also

- Carthusian MartyrsCarthusian MartyrsThe Carthusian Martyrs were a group of monks of the London Charterhouse, the monastery of the Carthusian Order in central London, who were put to death by the English state from June 19, 1535 to September 20, 1537. The method of execution was hanging, disembowelling while still alive and then...

- Connected Histories