John Couch Adams

Encyclopedia

John Couch Adams was a British mathematician

and astronomer

. Adams was born in Laneast

, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge

. The Cornish

name Couch is pronounced "cooch".

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of Neptune

, using only mathematics

. The calculations were made to explain discrepancies with Uranus

's orbit

and the laws

of Kepler

and Newton

. At the same time, but unknown to each other, the same calculations were made by Urbain Le Verrier. Le Verrier would assist Berlin Observatory astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle

in locating the planet

on 23 September 1846, which was found within 1° of its predicted location, a point

in Aquarius

. (There was, and to some extent still is, some controversy over the apportionment of credit for the discovery; see Discovery of Neptune

.)

He was Lowndean Professor

at the University of Cambridge

for thirty-three years from 1859 to his death. He won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

in 1866. In 1884, he attended the International Meridian Conference

as a delegate for Britain

.

A crater

on the Moon

is jointly named after him, Walter Sydney Adams

and Charles Hitchcock Adams

. Neptune's outermost known ring

and the asteroid

1996 Adams

are also named after him. The Adams Prize

, presented by the University of Cambridge, commemorates his prediction of the position of Neptune. His personal library is now in the care of Cambridge University Library

.

, near Launceston, Cornwall, the eldest of seven children. His parents were Thomas Adams (1788–1859), a poor tenant farmer

, and his wife, Tabitha Knill Grylls (1796–1866). The family were devout Wesleyan

s who enjoyed music

and among John's brothers, Thomas became a missionary

, George a farmer

, and William Grylls Adams

, professor of natural philosophy

and astronomy

at King's College London

. Tabitha was a farmer's daughter but had received a rudimentary education from John Couch, her uncle, whose small library she had inherited. John was intrigued by the astronomy books from an early age.

John attended the Laneast village school where he acquired some Greek

and algebra

. From there, he went, at the age of twelve, to Devonport

, where his mother's cousin, the Rev. John Couch Grylls, kept a private school. There he learned classics

but was largely self-taught in mathematics

, studying in the Library of Devonport Mechanics' Institute and reading Rees's Cyclopaedia

and Samuel Vince

's Fluxions. He observed Halley's comet in 1835 from Landulph

and the following year started to make his own astronomical calculations, predictions and observations, engaging in private tutoring to finance his activities.

In 1836, his mother inherited a small estate at Badharlick

and his promise as a mathematician induced his parents to send him to the University of Cambridge

. In October 1839 he entered as a sizar

at St John's College

, graduating B.A.

in 1843 as the senior wrangler and first Smith's prize

man of his year.

had published astronomical tables of the orbit

of Uranus

, making predictions of future positions based on Newton's laws of motion

and gravitation. Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize some perturbing body. Adams learnt of the irregularities while still an undergraduate and became convinced of the "perturbation" theory. Adams believed, in the face of anything that had been attempted before, that he could use the observed data on Uranus, and utilising nothing more than Newton's law of gravitation, deduce the mass

, position and orbit of the perturbing body. On the 3rd of July 1841, he noted his intention to work on the problem.

After his final examination

After his final examination

s in 1843, Adams was elected fellow of his college and spent the summer vacation in Cornwall calculating the first of six iterations. While he worked on the problem back in Cambridge, he tutored undergraduates, sending money home to educate his brothers, and even taught Mrs. Ireland, his bedmaker, to read.

Supposedly, Adams communicated his work to James Challis

, director of the Cambridge Observatory

, in mid-September 1845 but there is some controversy as to how. On 21 October 1845, Adams, returning from a Cornwall vacation, without appointment, twice called on Astronomer Royal

George Biddell Airy

in Greenwich

. Failing to find him at home, Adams reputedly left a manuscript of his solution, again without the detailed calculations. Airy responded with a letter to Adams asking for some clarification. It appears that Adams did not regard the question as "trivial", as is often alleged, but he failed to complete a response. Various theories have been discussed as to Adams's failure to reply, such as his general nervousness, procrastination and disorganisation.

Meanwhile, Urbain Le Verrier, on 10 November 1845, presented to the Académie des sciences in Paris a memoir on Uranus, showing that the pre-existing theory failed to account for its motion. On reading Le Verrier's memoir, Airy was struck by the coincidence and initiated a desperate race for English priority in discovery of the planet. The search was begun by a laborious method on 29 July. Only after the discovery of Neptune on 23 September 1846 had been announced in Paris did it become apparent that Neptune had been observed on 8 and 12 August but because Challis lacked an up-to-date star-map it was not recognized as a planet.

A keen controversy arose in France and England as to the merits of the two astronomers. As the facts became known, there was wide recognition that the two astronomers had independently solved the problem of Uranus, and each was ascribed equal importance. However, there have been subsequent assertions that "The Brits Stole Neptune" and that Adams's British contemporaries retrospectively ascribed him more credit than he was due. But it is also notable (and not included in some of the foregoing discussion references) that Adams himself publicly acknowledged Le Verrier's priority and credit (not forgetting to mention the role of Galle) in the paper that he gave 'On the Perturbations of Uranus' to the Royal Astronomical Society in November 1846:-

Adams held no bitterness towards Challis or Airy and acknowledged his own failure to convince the astronomical world:

, which possessed greater freedom, elected him in the following year to a lay fellowship which he held for the rest of his life.

Despite the fame of his work on Neptune, Adams also did much important work on gravitational astronomy and terrestrial magnetism. He was particularly adept at fine numerical calculations, often making substantial revisions to the contributions of his predecessors. However, he was "extraordinarily uncompetitive, reluctant to publish imperfect work to stimulate debate or claim priority, averse to correspondence about it, and forgetful in practical matters". It has been suggested that these are symptom

s of Asperger syndrome

which would also be consistent with the "repetitive behaviours and restricted interests" necessary to perform the Neptune calculations, in addition to his difficulties in personal interaction with Challis and Airy.

In 1852, he published new and accurate tables of the moon's parallax

, which superseded Johann Karl Burckhardt

's, and supplied corrections to the theories of Marie-Charles Damoiseau

, Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana

, and Philippe Gustave Doulcet.

He had hoped that this work would leverage him into the vacant post as superintendent of HM Nautical Almanac Office

but John Russell Hind

was preferred, Adams lacking the necessary ability as an organiser and administrator.

's mean rate of motion relative to the stars had been treated as a constant rate, but in 1695, Edmond Halley

had suggested that this mean rate was gradually increasing. Later, during the eighteenth century, Richard Dunthorne

estimated the rate as +10" (arcseconds/century2) in terms of the resulting difference in lunar longitude, an effect that became known as the secular acceleration of the Moon. Pierre-Simon Laplace had given an explanation

in 1787 in terms of changes in the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit. He considered only the radial gravitational force on the Moon

, from the Sun

and Earth

but obtained close agreement with the historical record of observations.

In 1820, at the insistence of the Académie des sciences, Damoiseau, Plana and Francesco Carlini

revisited Laplace's work, investigating quadratic

and higher-order perturbing terms, and obtained similar results, again addressing only a radial, and neglecting tangential, gravitational force on the Moon. Hansen obtained similar results in 1842 and 1847.

In 1853, Adams published a paper showing that, while tangential terms vanish in the first-order theory of Laplace, they become substantial when quadratic terms are admitted. Small terms integrated

in time come to have large effects and Adams concluded that Plana had overestimated the secular acceleration by approximately 1.66" per century.

At first, Le Verrier rejected Adams's results. In 1856, Plana admitted Adams's conclusions, claiming to have revised his own analysis and arrived at the same results. However, he soon recanted, publishing a third result different both from Adams's and Plana's own earlier work. Delaunay in 1859 calculated the fourth-order term and duplicated Adams's result leading Adams to publish his own calculations for the fifth, sixth and seventh-order terms. Adams now calculated that only 5.7" of the observed 11" was accounted for by gravitational effects.

Later that year, Philippe Gustave Doulcet, Comte de Pontécoulant published a claim that the tangential force could have no effect though Peter Andreas Hansen

, who seems to have cast himself in the role of arbitrator, declared that the burden of proof rested on Pontécoulant, while lamenting the need to discover a further effect to account for the balance. Much of the controversy centred around the convergence of the power series expansion used and, in 1860, Adams duplicated his results without using a power series. Sir John Lubbock

also duplicated Adams's results and Plana finally concurred. Adams's view was ultimately accepted and further developed, winning him the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

in 1866. The unexplained drift is now known to be due to tidal acceleration

.

In 1858 Adams became professor of mathematics at the University of St Andrews

, but lectured only for a session, before returning to Cambridge for the Lowndean professorship of astronomy and geometry. Two years later he succeeded Challis as director of the Cambridge Observatory

, a post Adams held until his death.

The great meteor shower

The great meteor shower

of November 1866 turned his attention to the Leonids

, whose probable path and period had already been discussed and predicted by Hubert Anson Newton

in 1864. Newton had asserted that the longitude of the ascending node

, that marked where the shower would occur, was increasing and the problem of explaining this variation attracted some of Europe's leading astronomers.

Using a powerful and elaborate analysis, Adams ascertained that this cluster of meteors, which belongs to the solar system, traverses an elongated ellipse in 33.25 years, and is subject to definite perturbations from the larger planets, Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. These results were published in 1867.

Some experts consider this Adams's most substantial achievement. His "definitive orbit" for the Leonids coincided with that of the comet

55P/Tempel-Tuttle

and therefore suggested the, later widely accepted, close relationship between comets and meteors.

Ten years later, George William Hill

Ten years later, George William Hill

described a novel and elegant method for attacking the problem of lunar motion. Adams briefly announced his own unpublished work in the same field, which, following a parallel course had confirmed and supplemented Hill's.

Over a period of forty years, he periodically addressed the determination of the constants in Carl Friedrich Gauss

's theory of terrestrial magnetism. Again, the calculations involved great labour, and were not published during his lifetime. They were edited by his brother, William Grylls Adams

, and appear in the second volume of the collected Scientific Papers. Numerical computation of this kind might almost be described as his pastime. He calculated the Euler–Mascheroni constant

, perhaps somewhat eccentrically, to 236 decimal places and evaluated the Bernoulli numbers up to the 62nd.

Adams had boundless admiration for Newton and his writings and many of his papers bear the cast of Newton's thought. In 1872, Isaac Newton Wallop, 5th Earl of Portsmouth donated his private collection of Newton's papers to Cambridge University. Adams and G. G. Stokes took on the task or arranging the material, publishing a catalogue in 1888.

The post of Astronomer Royal

was offered him in 1881, but he preferred to pursue his peaceful course of teaching and research in Cambridge. He was British delegate to the International Meridian Conference

at Washington

in 1884, when he also attended the meetings of the British Association at Montreal

and of the American Association at Philadelphia.

in Cambridge, near his home. In 1863 he had married Miss Eliza Bruce, of Dublin, who survived him. His wealth at death was £32,434 (£2.6 million at 2003 prices).

Mathematician

A mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

and astronomer

Astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist who studies celestial bodies such as planets, stars and galaxies.Historically, astronomy was more concerned with the classification and description of phenomena in the sky, while astrophysics attempted to explain these phenomena and the differences between them using...

. Adams was born in Laneast

Laneast

Laneast is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated above the River Inny valley approximately six miles west of Launceston. The population in the 2001 census was 164.-Geography:...

, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

. The Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

name Couch is pronounced "cooch".

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of Neptune

Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest planet from the Sun in the Solar System. Named for the Roman god of the sea, it is the fourth-largest planet by diameter and the third largest by mass. Neptune is 17 times the mass of Earth and is slightly more massive than its near-twin Uranus, which is 15 times...

, using only mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

. The calculations were made to explain discrepancies with Uranus

Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It has the third-largest planetary radius and fourth-largest planetary mass in the Solar System. It is named after the ancient Greek deity of the sky Uranus , the father of Cronus and grandfather of Zeus...

's orbit

Orbit

In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the Solar System...

and the laws

Physical law

A physical law or scientific law is "a theoretical principle deduced from particular facts, applicable to a defined group or class of phenomena, and expressible by the statement that a particular phenomenon always occurs if certain conditions be present." Physical laws are typically conclusions...

of Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

and Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

. At the same time, but unknown to each other, the same calculations were made by Urbain Le Verrier. Le Verrier would assist Berlin Observatory astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle

Johann Gottfried Galle

Johann Gottfried Galle was a German astronomer at the Berlin Observatory who, on 23 September 1846, with the assistance of student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, was the first person to view the planet Neptune, and know what he was looking at...

in locating the planet

Planet

A planet is a celestial body orbiting a star or stellar remnant that is massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity, is not massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion, and has cleared its neighbouring region of planetesimals.The term planet is ancient, with ties to history, science,...

on 23 September 1846, which was found within 1° of its predicted location, a point

Point (geometry)

In geometry, topology and related branches of mathematics a spatial point is a primitive notion upon which other concepts may be defined. In geometry, points are zero-dimensional; i.e., they do not have volume, area, length, or any other higher-dimensional analogue. In branches of mathematics...

in Aquarius

Aquarius (constellation)

Aquarius is a constellation of the zodiac, situated between Capricornus and Pisces. Its name is Latin for "water-bearer" or "cup-bearer", and its symbol is , a representation of water....

. (There was, and to some extent still is, some controversy over the apportionment of credit for the discovery; see Discovery of Neptune

Discovery of Neptune

Neptune was mathematically predicted before it was directly observed. With a prediction by Urbain Le Verrier, telescopic observations confirming the existence of a major planet were made on the night of September 23, 1846, and into the early morning of the 24th, at the Berlin Observatory, by...

.)

He was Lowndean Professor

Lowndean Professor of Astronomy and Geometry

The Lowndean chair of Astronomy and Geometry is one of the two major Professorships in Astronomy at Cambridge University, alongside the Plumian Professorship...

at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

for thirty-three years from 1859 to his death. He won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

-History:In the early years, more than one medal was often awarded in a year, but by 1833 only one medal was being awarded per year. This caused a problem when Neptune was discovered in 1846, because many felt an award should jointly be made to John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier...

in 1866. In 1884, he attended the International Meridian Conference

International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States to determine the Prime Meridian of the world. The conference was held at the request of U.S. President Chester A...

as a delegate for Britain

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

.

A crater

Impact crater

In the broadest sense, the term impact crater can be applied to any depression, natural or manmade, resulting from the high velocity impact of a projectile with a larger body...

on the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

is jointly named after him, Walter Sydney Adams

Walter Sydney Adams

Walter Sydney Adams was an American astronomer.-Life and work:He was born in Antioch, Syria to missionary parents, and was brought to the U.S. in 1885 He graduated from Dartmouth College in 1898, then continued his education in Germany...

and Charles Hitchcock Adams

Charles Hitchcock Adams

Charles Hitchcock Adams was an amateur American astronomer, and father of photographer Ansel Adams....

. Neptune's outermost known ring

Rings of Neptune

The rings of Neptune consist primarily of five principal rings predicted in 1984 by André Brahic and imaged in 1989 by the Voyager 2 spacecraft...

and the asteroid

Asteroid

Asteroids are a class of small Solar System bodies in orbit around the Sun. They have also been called planetoids, especially the larger ones...

1996 Adams

1996 Adams

1996 Adams is the name of an asteroid that was discovered at Goethe Link Observatory near Brooklyn, Indiana by the Indiana Asteroid Program. It is named in honour of John Couch Adams, British mathematician and astronomer who, simultaneously with Urbain Le Verrier, predicted the existence and...

are also named after him. The Adams Prize

Adams Prize

The Adams Prize is awarded each year by the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and St John's College to a young, UK based mathematician for first-class international research in the Mathematical Sciences....

, presented by the University of Cambridge, commemorates his prediction of the position of Neptune. His personal library is now in the care of Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library

The Cambridge University Library is the centrally-administered library of Cambridge University in England. It comprises five separate libraries:* the University Library main building * the Medical Library...

.

Early life

Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at LaneastLaneast

Laneast is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated above the River Inny valley approximately six miles west of Launceston. The population in the 2001 census was 164.-Geography:...

, near Launceston, Cornwall, the eldest of seven children. His parents were Thomas Adams (1788–1859), a poor tenant farmer

Tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is one who resides on and farms land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management; while tenant farmers contribute their labor along with at times varying...

, and his wife, Tabitha Knill Grylls (1796–1866). The family were devout Wesleyan

Methodist Church of Great Britain

The Methodist Church of Great Britain is the largest Wesleyan Methodist body in the United Kingdom, with congregations across Great Britain . It is the United Kingdom's fourth largest Christian denomination, with around 300,000 members and 6,000 churches...

s who enjoyed music

Music

Music is an art form whose medium is sound and silence. Its common elements are pitch , rhythm , dynamics, and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture...

and among John's brothers, Thomas became a missionary

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

, George a farmer

Farmer

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, who raises living organisms for food or raw materials, generally including livestock husbandry and growing crops, such as produce and grain...

, and William Grylls Adams

William Grylls Adams

William Grylls Adams FRS was professor of Natural Philosophy at King's College, London.William Grylls Adams was a younger brother of John Couch Adams . He graduated from St...

, professor of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

and astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

at King's College London

King's College London

King's College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and a constituent college of the federal University of London. King's has a claim to being the third oldest university in England, having been founded by King George IV and the Duke of Wellington in 1829, and...

. Tabitha was a farmer's daughter but had received a rudimentary education from John Couch, her uncle, whose small library she had inherited. John was intrigued by the astronomy books from an early age.

John attended the Laneast village school where he acquired some Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

and algebra

Algebra

Algebra is the branch of mathematics concerning the study of the rules of operations and relations, and the constructions and concepts arising from them, including terms, polynomials, equations and algebraic structures...

. From there, he went, at the age of twelve, to Devonport

Devonport, Devon

Devonport, formerly named Plymouth Dock or just Dock, is a district of Plymouth in the English county of Devon, although it was, at one time, the more important settlement. It became a county borough in 1889...

, where his mother's cousin, the Rev. John Couch Grylls, kept a private school. There he learned classics

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

but was largely self-taught in mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, studying in the Library of Devonport Mechanics' Institute and reading Rees's Cyclopaedia

Rees's Cyclopaedia

Rees's Cyclopædia, or The New Cyclopaedia, or, Universal Dictionary of the Arts and Sciences was an important 19th Century encyclopaedia which was regarded by some as subversive when it first appeared. It was edited by Revd...

and Samuel Vince

Samuel Vince

Samuel Vince was an English clergyman, mathematician and astronomer at the University of Cambridge.The son of a plasterer, Vince was admitted as a sizar to Caius College, Cambridge in 1771. In 1775 he was Senior Wrangler at Cambridge. Migrating to Sidney Sussex College in 1777, he gained his M.A....

's Fluxions. He observed Halley's comet in 1835 from Landulph

Landulph

Landulph is a hamlet and a rural civil parish in south-east Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated about 3 miles north of Saltash in the St Germans Registration District....

and the following year started to make his own astronomical calculations, predictions and observations, engaging in private tutoring to finance his activities.

In 1836, his mother inherited a small estate at Badharlick

Badharlick

Badharlick is a hamlet in Cornwall, situated half way between the villages of Tregeare and Egloskerry....

and his promise as a mathematician induced his parents to send him to the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

. In October 1839 he entered as a sizar

Sizar

At Trinity College, Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is a student who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined job....

at St John's College

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

, graduating B.A.

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

in 1843 as the senior wrangler and first Smith's prize

Smith's Prize

The Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in theoretical Physics, mathematics and applied mathematics at the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England.- History :...

man of his year.

Discovery of Neptune

In 1821, Alexis BouvardAlexis Bouvard

Alexis Bouvard was a French astronomer. He is particularly noted for his careful observations of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus and his hypothesis of the existence of an eighth planet in the solar system.-Life:...

had published astronomical tables of the orbit

Orbit

In physics, an orbit is the gravitationally curved path of an object around a point in space, for example the orbit of a planet around the center of a star system, such as the Solar System...

of Uranus

Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It has the third-largest planetary radius and fourth-largest planetary mass in the Solar System. It is named after the ancient Greek deity of the sky Uranus , the father of Cronus and grandfather of Zeus...

, making predictions of future positions based on Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that form the basis for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between the forces acting on a body and its motion due to those forces...

and gravitation. Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize some perturbing body. Adams learnt of the irregularities while still an undergraduate and became convinced of the "perturbation" theory. Adams believed, in the face of anything that had been attempted before, that he could use the observed data on Uranus, and utilising nothing more than Newton's law of gravitation, deduce the mass

Mass

Mass can be defined as a quantitive measure of the resistance an object has to change in its velocity.In physics, mass commonly refers to any of the following three properties of matter, which have been shown experimentally to be equivalent:...

, position and orbit of the perturbing body. On the 3rd of July 1841, he noted his intention to work on the problem.

Final examination

A final examination is a test given to students at the end of a course of study or training. Although the term can be used in the context of physical training, it most often occurs in the academic world...

s in 1843, Adams was elected fellow of his college and spent the summer vacation in Cornwall calculating the first of six iterations. While he worked on the problem back in Cambridge, he tutored undergraduates, sending money home to educate his brothers, and even taught Mrs. Ireland, his bedmaker, to read.

Supposedly, Adams communicated his work to James Challis

James Challis

James Challis FRS was an English clergyman, physicist and astronomer. Plumian Professor and director of the Cambridge Observatory, he investigated a wide range of physical phenomena though made few lasting contributions outside astronomy...

, director of the Cambridge Observatory

Cambridge Observatory

Cambridge Observatory is an astronomical observatory at the University of Cambridge in the East of England. It was first established in 1823 and is now part of the site of the Institute of Astronomy...

, in mid-September 1845 but there is some controversy as to how. On 21 October 1845, Adams, returning from a Cornwall vacation, without appointment, twice called on Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the second is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834....

George Biddell Airy

George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy PRS KCB was an English mathematician and astronomer, Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881...

in Greenwich

Greenwich

Greenwich is a district of south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich.Greenwich is best known for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time...

. Failing to find him at home, Adams reputedly left a manuscript of his solution, again without the detailed calculations. Airy responded with a letter to Adams asking for some clarification. It appears that Adams did not regard the question as "trivial", as is often alleged, but he failed to complete a response. Various theories have been discussed as to Adams's failure to reply, such as his general nervousness, procrastination and disorganisation.

Meanwhile, Urbain Le Verrier, on 10 November 1845, presented to the Académie des sciences in Paris a memoir on Uranus, showing that the pre-existing theory failed to account for its motion. On reading Le Verrier's memoir, Airy was struck by the coincidence and initiated a desperate race for English priority in discovery of the planet. The search was begun by a laborious method on 29 July. Only after the discovery of Neptune on 23 September 1846 had been announced in Paris did it become apparent that Neptune had been observed on 8 and 12 August but because Challis lacked an up-to-date star-map it was not recognized as a planet.

A keen controversy arose in France and England as to the merits of the two astronomers. As the facts became known, there was wide recognition that the two astronomers had independently solved the problem of Uranus, and each was ascribed equal importance. However, there have been subsequent assertions that "The Brits Stole Neptune" and that Adams's British contemporaries retrospectively ascribed him more credit than he was due. But it is also notable (and not included in some of the foregoing discussion references) that Adams himself publicly acknowledged Le Verrier's priority and credit (not forgetting to mention the role of Galle) in the paper that he gave 'On the Perturbations of Uranus' to the Royal Astronomical Society in November 1846:-

Adams held no bitterness towards Challis or Airy and acknowledged his own failure to convince the astronomical world:

Adams' style of working

His lay fellowship at St John's College came to an end in 1852, and the existing statutes did not permit his re-election. However, Pembroke CollegePembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college has over seven hundred students and fellows, and is the third oldest college of the university. Physically, it is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from almost every century since its...

, which possessed greater freedom, elected him in the following year to a lay fellowship which he held for the rest of his life.

Despite the fame of his work on Neptune, Adams also did much important work on gravitational astronomy and terrestrial magnetism. He was particularly adept at fine numerical calculations, often making substantial revisions to the contributions of his predecessors. However, he was "extraordinarily uncompetitive, reluctant to publish imperfect work to stimulate debate or claim priority, averse to correspondence about it, and forgetful in practical matters". It has been suggested that these are symptom

Symptom

A symptom is a departure from normal function or feeling which is noticed by a patient, indicating the presence of disease or abnormality...

s of Asperger syndrome

Asperger syndrome

Asperger's syndrome that is characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction, alongside restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior and interests. It differs from other autism spectrum disorders by its relative preservation of linguistic and cognitive development...

which would also be consistent with the "repetitive behaviours and restricted interests" necessary to perform the Neptune calculations, in addition to his difficulties in personal interaction with Challis and Airy.

In 1852, he published new and accurate tables of the moon's parallax

Parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. The term is derived from the Greek παράλλαξις , meaning "alteration"...

, which superseded Johann Karl Burckhardt

Johann Karl Burckhardt

Johann Karl Burckhardt was a German-born astronomer and mathematician who later became a naturalized French citizen....

's, and supplied corrections to the theories of Marie-Charles Damoiseau

Marie-Charles Damoiseau

Baron Marie-Charles-Théodore de Damoiseau de Montfort was a French astronomer.Damoiseau left France during the French Revolution and worked as assistant director of the Lisbon Observatory. He returned to France in 1807.In 1825, he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences...

, Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana

Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana

Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana was an Italian astronomer and mathematician.He was born in Voghera, Italy to Antonio Maria Plana and Giacoboni. At the age of 15 he was sent to live with his uncles in Grenoble to complete his education. In 1800 he entered the École Polytechnique, and was one of the...

, and Philippe Gustave Doulcet.

He had hoped that this work would leverage him into the vacant post as superintendent of HM Nautical Almanac Office

HM Nautical Almanac Office

Her Majesty's Nautical Almanac Office , now part of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, was established in 1832 on the site of the Royal Greenwich Observatory , where the Nautical Almanac had been published since 1767...

but John Russell Hind

John Russell Hind

John Russell Hind FRS was an English astronomer.- Life and work :John Russell Hind was born in 1823 in Nottingham, the son of lace manufacturer John Hind, and was educated at Nottingham High School...

was preferred, Adams lacking the necessary ability as an organiser and administrator.

Lunar theory — Secular acceleration of the Moon

Since ancient times, the MoonMoon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

's mean rate of motion relative to the stars had been treated as a constant rate, but in 1695, Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley FRS was an English astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist who is best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley's Comet. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, following in the footsteps of John Flamsteed.-Biography and career:Halley...

had suggested that this mean rate was gradually increasing. Later, during the eighteenth century, Richard Dunthorne

Richard Dunthorne

Richard Dunthorne was an English astronomer and surveyor, who worked in Cambridge as astronomical and scientific assistant to Roger Long , and also concurrently for many years as surveyor to the Bedford Level Corporation.-Life and work:There are short biographical notes of Dunthorne, one in...

estimated the rate as +10" (arcseconds/century2) in terms of the resulting difference in lunar longitude, an effect that became known as the secular acceleration of the Moon. Pierre-Simon Laplace had given an explanation

Lunar theory

Lunar theory attempts to account for the motions of the Moon. There are many irregularities in the Moon's motion, and many attempts have been made over a long history to account for them. After centuries of being heavily problematic, the lunar motions are nowadays modelled to a very high degree...

in 1787 in terms of changes in the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit. He considered only the radial gravitational force on the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

, from the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

and Earth

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and the densest and fifth-largest of the eight planets in the Solar System. It is also the largest of the Solar System's four terrestrial planets...

but obtained close agreement with the historical record of observations.

In 1820, at the insistence of the Académie des sciences, Damoiseau, Plana and Francesco Carlini

Francesco Carlini

Francesco Carlini was an Italian astronomer. Born in Milan, he became director of the observatory there in 1832. He published Nuove tavole de moti apparenti del sole in 1832. In 1810, he had already published Esposizione di un nuovo metodo di construire le taole astronomiche applicato alle...

revisited Laplace's work, investigating quadratic

Quadratic function

A quadratic function, in mathematics, is a polynomial function of the formf=ax^2+bx+c,\quad a \ne 0.The graph of a quadratic function is a parabola whose axis of symmetry is parallel to the y-axis....

and higher-order perturbing terms, and obtained similar results, again addressing only a radial, and neglecting tangential, gravitational force on the Moon. Hansen obtained similar results in 1842 and 1847.

In 1853, Adams published a paper showing that, while tangential terms vanish in the first-order theory of Laplace, they become substantial when quadratic terms are admitted. Small terms integrated

Integral

Integration is an important concept in mathematics and, together with its inverse, differentiation, is one of the two main operations in calculus...

in time come to have large effects and Adams concluded that Plana had overestimated the secular acceleration by approximately 1.66" per century.

At first, Le Verrier rejected Adams's results. In 1856, Plana admitted Adams's conclusions, claiming to have revised his own analysis and arrived at the same results. However, he soon recanted, publishing a third result different both from Adams's and Plana's own earlier work. Delaunay in 1859 calculated the fourth-order term and duplicated Adams's result leading Adams to publish his own calculations for the fifth, sixth and seventh-order terms. Adams now calculated that only 5.7" of the observed 11" was accounted for by gravitational effects.

Later that year, Philippe Gustave Doulcet, Comte de Pontécoulant published a claim that the tangential force could have no effect though Peter Andreas Hansen

Peter Andreas Hansen

Peter Andreas Hansen was a Danish astronomer, was born at Tønder, Schleswig.-Biography:The son of a goldsmith, Hansen learned the trade of a watchmaker at Flensburg, and exercised it at Berlin and Tønder, 1818–1820...

, who seems to have cast himself in the role of arbitrator, declared that the burden of proof rested on Pontécoulant, while lamenting the need to discover a further effect to account for the balance. Much of the controversy centred around the convergence of the power series expansion used and, in 1860, Adams duplicated his results without using a power series. Sir John Lubbock

Sir John Lubbock, 3rd Baronet

Sir John William Lubbock, 3rd Baronet was an English banker, barrister, mathematician and astronomer.He was born in Westminster, the son of Sir John William Lubbock, of the Lubbock & Co bank. He was educated at Eton and then Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1825...

also duplicated Adams's results and Plana finally concurred. Adams's view was ultimately accepted and further developed, winning him the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

-History:In the early years, more than one medal was often awarded in a year, but by 1833 only one medal was being awarded per year. This caused a problem when Neptune was discovered in 1846, because many felt an award should jointly be made to John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier...

in 1866. The unexplained drift is now known to be due to tidal acceleration

Tidal acceleration

Tidal acceleration is an effect of the tidal forces between an orbiting natural satellite , and the primary planet that it orbits . The "acceleration" is usually negative, as it causes a gradual slowing and recession of a satellite in a prograde orbit away from the primary, and a corresponding...

.

In 1858 Adams became professor of mathematics at the University of St Andrews

University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews, informally referred to as "St Andrews", is the oldest university in Scotland and the third oldest in the English-speaking world after Oxford and Cambridge. The university is situated in the town of St Andrews, Fife, on the east coast of Scotland. It was founded between...

, but lectured only for a session, before returning to Cambridge for the Lowndean professorship of astronomy and geometry. Two years later he succeeded Challis as director of the Cambridge Observatory

Cambridge Observatory

Cambridge Observatory is an astronomical observatory at the University of Cambridge in the East of England. It was first established in 1823 and is now part of the site of the Institute of Astronomy...

, a post Adams held until his death.

The Leonids

Meteor shower

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere at extremely high speeds on parallel trajectories. Most meteors are smaller...

of November 1866 turned his attention to the Leonids

Leonids

The Leonids is a prolific meteor shower associated with the comet Tempel-Tuttle. The Leonids get their name from the location of their radiant in the constellation Leo: the meteors appear to radiate from that point in the sky. They tend to peak in November.Earth moves through the meteoroid...

, whose probable path and period had already been discussed and predicted by Hubert Anson Newton

Hubert Anson Newton

Hubert Anson Newton was an American astronomer and mathematician, noted for his research on meteors.He was born at Sherburne, New York, and graduated from Yale in 1850. The Mathematics Genealogy Project lists his advisor as Michel Chasles. In 1855, he was appointed professor of mathematics at Yale...

in 1864. Newton had asserted that the longitude of the ascending node

Longitude of the ascending node

The longitude of the ascending node is one of the orbital elements used to specify the orbit of an object in space. It is the angle from a reference direction, called the origin of longitude, to the direction of the ascending node, measured in a reference plane...

, that marked where the shower would occur, was increasing and the problem of explaining this variation attracted some of Europe's leading astronomers.

Using a powerful and elaborate analysis, Adams ascertained that this cluster of meteors, which belongs to the solar system, traverses an elongated ellipse in 33.25 years, and is subject to definite perturbations from the larger planets, Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. These results were published in 1867.

Some experts consider this Adams's most substantial achievement. His "definitive orbit" for the Leonids coincided with that of the comet

Comet

A comet is an icy small Solar System body that, when close enough to the Sun, displays a visible coma and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena are both due to the effects of solar radiation and the solar wind upon the nucleus of the comet...

55P/Tempel-Tuttle

55P/Tempel-Tuttle

55P/Tempel–Tuttle is a comet that was independently discovered by Ernst Tempel on December 19, 1865 and by Horace Parnell Tuttle on January 6, 1866.It is the parent body of the Leonid meteor shower...

and therefore suggested the, later widely accepted, close relationship between comets and meteors.

Later career

George William Hill

George William Hill , was an American astronomer and mathematician.Hill was born in New York City, New York to painter and engraver John William Hill. and Catherine Smith Hill. He moved to West Nyack with his family when he was eight years old. After attending high school, Hill graduated from...

described a novel and elegant method for attacking the problem of lunar motion. Adams briefly announced his own unpublished work in the same field, which, following a parallel course had confirmed and supplemented Hill's.

Over a period of forty years, he periodically addressed the determination of the constants in Carl Friedrich Gauss

Carl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss was a German mathematician and scientist who contributed significantly to many fields, including number theory, statistics, analysis, differential geometry, geodesy, geophysics, electrostatics, astronomy and optics.Sometimes referred to as the Princeps mathematicorum...

's theory of terrestrial magnetism. Again, the calculations involved great labour, and were not published during his lifetime. They were edited by his brother, William Grylls Adams

William Grylls Adams

William Grylls Adams FRS was professor of Natural Philosophy at King's College, London.William Grylls Adams was a younger brother of John Couch Adams . He graduated from St...

, and appear in the second volume of the collected Scientific Papers. Numerical computation of this kind might almost be described as his pastime. He calculated the Euler–Mascheroni constant

Euler–Mascheroni constant

The Euler–Mascheroni constant is a mathematical constant recurring in analysis and number theory, usually denoted by the lowercase Greek letter ....

, perhaps somewhat eccentrically, to 236 decimal places and evaluated the Bernoulli numbers up to the 62nd.

Adams had boundless admiration for Newton and his writings and many of his papers bear the cast of Newton's thought. In 1872, Isaac Newton Wallop, 5th Earl of Portsmouth donated his private collection of Newton's papers to Cambridge University. Adams and G. G. Stokes took on the task or arranging the material, publishing a catalogue in 1888.

The post of Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the second is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834....

was offered him in 1881, but he preferred to pursue his peaceful course of teaching and research in Cambridge. He was British delegate to the International Meridian Conference

International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States to determine the Prime Meridian of the world. The conference was held at the request of U.S. President Chester A...

at Washington

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

in 1884, when he also attended the meetings of the British Association at Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

and of the American Association at Philadelphia.

Honours

- He is reputed to have been offered a knighthood on Queen Victoria's 1847 Cambridge visit but to have declined, either out of modesty, or fear of the financial consequences of such social distinction;

- Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and SciencesAmerican Academy of Arts and SciencesThe American Academy of Arts and Sciences is an independent policy research center that conducts multidisciplinary studies of complex and emerging problems. The Academy’s elected members are leaders in the academic disciplines, the arts, business, and public affairs.James Bowdoin, John Adams, and...

, (1847); - Copley medalCopley MedalThe Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society of London for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science, and alternates between the physical sciences and the biological sciences"...

of the Royal SocietyRoyal SocietyThe Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, (1848); - Adams PrizeAdams PrizeThe Adams Prize is awarded each year by the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and St John's College to a young, UK based mathematician for first-class international research in the Mathematical Sciences....

, founded by the members of St John's College, to be given biennially for the best treatise on a mathematical subject (1848); - President of the Royal Astronomical SocietyRoyal Astronomical SocietyThe Royal Astronomical Society is a learned society that began as the Astronomical Society of London in 1820 to support astronomical research . It became the Royal Astronomical Society in 1831 on receiving its Royal Charter from William IV...

, (1851–1853 and 1874–1876).

Family and death

Five years later his health gave way, and after a long illness he died at the Cambridge Observatory on 21 January 1892, and is buried in the Parish of the Ascension Burial GroundAscension Parish Burial Ground, Cambridge

The Ascension Parish Burial Ground, formerly St Giles and St Peter's Parish, is a cemetery just off Huntingdon Road near the junction with Storey's Way in the northwest of Cambridge, England. It includes the graves of many Cambridge academics and non-conformists of the 19th and early 20th century...

in Cambridge, near his home. In 1863 he had married Miss Eliza Bruce, of Dublin, who survived him. His wealth at death was £32,434 (£2.6 million at 2003 prices).

Memorials

- Memorial in Westminster AbbeyWestminster AbbeyThe Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

with a portrait medallion, by Albert Bruce Joy; - A bust, by Joy in the hall of St John's College, Cambridge;

- Another youthful bust belongs to the Royal Astronomical Society;

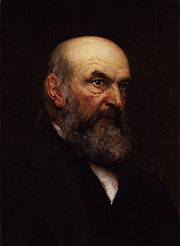

- Portraits by:

- Hubert von HerkomerHubert von HerkomerSir Hubert von Herkomer , British painter of German descent. He was also a pioneering film-director and a composer. Though a very successful portraitist, especially of men, he is mainly remembered for his earlier works that took a realistic approach to the conditions of life of the poor...

in Pembroke College; - Paul Raphael Montord in the combination room of St John's;

- Hubert von Herkomer

- There is a memorial tablet, with an inscription by Archbishop BensonEdward White BensonEdward White Benson was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1883 until his death.-Life:Edward White Benson was born in Highgate, Birmingham, the son of a Birmingham chemical manufacturer. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated BA in 1852...

in Truro CathedralTruro CathedralThe Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Truro is an Anglican cathedral located in the city of Truro, Cornwall, in the United Kingdom. It was built in the Gothic Revival architectural style fashionable during much of the nineteenth century, and is one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom...

; - Passmore Edwards erected a public institute in his honour at Launceston, near his birthplace.

- Adams NunatakAdams NunatakAdams Nunatak is a nunatak on the south side of Neptune Glacier, west of Cannonball Cliffs, in eastern Alexander Island. Mapped by Directorate of Overseas Surveys from satellite imagery supplied by NASA in cooperation with U.S. Geological Survey...

, a nunatak on Neptune Glacier in Alexander IslandAlexander IslandAlexander Island or Alexander I Island or Alexander I Land or Alexander Land is the largest island of Antarctica, with an area of lying in the Bellingshausen Sea west of the base of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which it is separated by Marguerite Bay and George VI Sound. Alexander Island lies off...

in Antarctica, is named after him

Obituaries

- The TimesThe TimesThe Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

, 22 January 1892, p. 6 col.d (link on this page) - [Anon.] (1891-2) Journal of the British Astronomical Association 2: 196–7

About Adams and the discovery of Neptune

from Project GutenbergProject Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks". Founded in 1971 by Michael S. Hart, it is the oldest digital library. Most of the items in its collection are the full texts of public domain books...

- [Anon.] (1911) "John Couch Adams, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Doggett, L. E. (1997) "Celestial mechanics", in

- Harrison, H. M (1994). Voyager in Time and Space: The Life of John Couch Adams, Cambridge Astronomer. Lewes: Book Guild, ISBN 0-86332-918-7

- Hutchins, R. (2004) "Adams, John Couch (1819–1892)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 23 August 2007

- Sheehan, W. et al. (2004). The Case of the Pilfered Planet - Did the British steal Neptune? Scientific American

By Adams

- Adams, J. C., ed. W. G. Adams & R. A. Sampson (1896–1900) The Scientific Papers of John Couch Adams, 2 vols, London: Cambridge University Press, with a memoir by J. W. L. GlaisherJames Whitbread Lee GlaisherJames Whitbread Lee Glaisher son of James Glaisher, the meteorologist, was a prolific English mathematician.He was educated at St Paul's School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was second wrangler in 1871...

:- Vol.1 (1896) Previously published writings;

- Vol.2 (1900) Manuscripts including the substance of his lectures on the Lunar Theory.

- A collection, virtually complete, of Adams's papers regarding the discovery of Neptune was presented by Mrs Adams to the library of St John's College, see: Sampson (1904), and also:

- "The collected papers of Prof. Adams", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 7 (1896–7)

- Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 53 184;

- Observatory, 15 174;

- NatureNature (journal)Nature, first published on 4 November 1869, is ranked the world's most cited interdisciplinary scientific journal by the Science Edition of the 2010 Journal Citation Reports...

, 34 565; 45 301; - Astronomical Journal, No.254;

- R. Grant, History of Physical Astronomy, p. 168; and

- Edinburgh ReviewEdinburgh ReviewThe Edinburgh Review, founded in 1802, was one of the most influential British magazines of the 19th century. It ceased publication in 1929. The magazine took its Latin motto judex damnatur ubi nocens absolvitur from Publilius Syrus.In 1984, the Scottish cultural magazine New Edinburgh Review,...

, No.381, p. 72.

- The papers were ultimately lodged with the Royal Greenwich Observatory and evacuated to Herstmonceux CastleHerstmonceux CastleHerstmonceux Castle is a brick-built Tudor castle near Herstmonceux, East Sussex, United Kingdom. From 1957 to 1988 its grounds were the home of the Royal Greenwich Observatory...

during World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. After the war, they were stolenTheftIn common usage, theft is the illegal taking of another person's property without that person's permission or consent. The word is also used as an informal shorthand term for some crimes against property, such as burglary, embezzlement, larceny, looting, robbery, shoplifting and fraud...

by Olin J. EggenOlin J. EggenOlin Jeuck Eggen was an American astronomer. Some sources incorrectly give his name as Olin Jenck Eggen.-Biography:...

and only recovered in 1998, hampering much historical research in the subject.

See also

- Intrigue at RAS and Cambridge Observatory from the biography of Richard Christopher CarringtonRichard Christopher CarringtonRichard Christopher Carrington was an English amateur astronomer whose 1859 astronomical observations demonstrated the existence of solar flares as well as suggesting their electrical influence upon the Earth and its aurorae; and whose 1863 records of sunspot observations revealed the differential...