.gif)

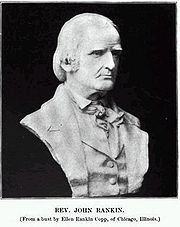

John Rankin (abolitionist)

Encyclopedia

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

minister, educator and abolitionist

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

. Upon moving to Ripley, Ohio

Ripley, Ohio

Ripley is a village in Brown County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River 50 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The population was 1,745 at the 2000 census.-History:...

in 1822, he became known as one of Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

's first and most active "conductors" on the Underground Railroad

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists,...

. Prominent pre-Civil War abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

, Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher was a prominent Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, abolitionist, and speaker in the mid to late 19th century...

and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe was an American abolitionist and author. Her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was a depiction of life for African-Americans under slavery; it reached millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and United Kingdom...

were influenced by Rankin's writings and work in the anti-slavery movement.

When Beecher was asked after the end of the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, "Who abolished slavery?," she answered, "Reverend John Rankin and his sons did."

Early career

Dandridge, Tennessee

Dandridge is a town in Jefferson County, Tennessee, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County. It is part of the Morristown, Tennessee Metropolitan Statistical Area....

, Jefferson County, Tennessee

Jefferson County, Tennessee

*...

, and raised in a strict Calvinist

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

home. Beginning at the age of eight, his view of the world and his religious faith were deeply affected by two things — the revivals of the Second Great Awakening

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Christian revival movement during the early 19th century in the United States. The movement began around 1800, had begun to gain momentum by 1820, and was in decline by 1870. The Second Great Awakening expressed Arminian theology, by which every person could be...

that were sweeping through the Appalachian region

Appalachia

Appalachia is a term used to describe a cultural region in the eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York state to northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Canada to Cheaha Mountain in the U.S...

, and the incipient slave rebellion

Slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by slaves. Slave rebellions have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery, and are amongst the most feared events for slaveholders...

led by Gabriel Prosser in 1800. (Hagedorn, pp. 22–23)

He attended Washington College

Washington College Academy

Washington College Academy is a private Presbyterian-affiliated educational institution located in Limestone, Tennessee. Founded in 1780 by Doctor of Divinity Samuel Doak, the Academy for many years offered accredited college, junior college and college preparatory instruction to day and boarding...

at Jonesborough

Jonesborough, Tennessee

Jonesborough is a town in and the county seat of Washington County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The population was 4,168 at the 2000 census...

, and soon after married Jean Lowry

Jean Lowry Rankin

Jean Lowry Rankin was an American was an Abolitionist and pioneer in the anti-slavery movement. With her husband John Rankin she assisted 2000 slaves in their journey to freedom along the Underground Railroad...

. In 1814, he became a Presbyterian minister.

Not a natural public speaker, Rankin worked hard while at Jefferson County Presbyterian Church simply to deliver an effective sermon. Within a few months, however, despite Tennessee's status as a slave state

Slave state

In the United States of America prior to the American Civil War, a slave state was a U.S. state in which slavery was legal, whereas a free state was one in which slavery was either prohibited from its entry into the Union or eliminated over time...

, he summoned the courage to speak against "all forms of oppression" and then, specifically, slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. He was shocked when his elders responded by telling him that he should consider leaving Tennessee if he intended ever to oppose slavery from the pulpit again. He knew that his faith would not allow him to keep his views to himself, so he decided to move his family to the town of Ripley

Ripley, Ohio

Ripley is a village in Brown County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River 50 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The population was 1,745 at the 2000 census.-History:...

across the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

in the free state of Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

, where he had heard from family members that a number of anti-slavery Virginians had settled.

On the way north, Rankin stopped to preach at Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

and Paris, Kentucky

Paris, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 9,183 people, 3,857 households, and 2,487 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 4,222 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 84.23% White, 12.71% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.16%...

and learned about the need for a minister at Concord Presbyterian Church in Carlisle

Carlisle, Kentucky

Carlisle is a city in Nicholas County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 1,917 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Nicholas County...

. The congregation had been involved in anti-slavery activities as far back as 1807 when they and twelve other churches formed the Kentucky Abolition Society, and Rankin's deepening anti-slavery views were nurtured there by his listeners. He remained for four years and started a school for slaves; within a year, however, they were driven first from a schoolhouse to an empty house, and then to his friend's kitchen by club-carrying mobs, and the students finally stopped coming. Spurred by a financial crisis in the area, Rankin decided to complete his family's journey to Ripley. On the night of December 31, 1821 – January 1, 1822, he rowed his family across the icy river.

Ripley and the Underground Railroad

In 1829, Rankin moved his wife and nine children (of an eventual total of thirteen) to a house at the top of a 540-foot-high hill that provided a wide view of the village, the River and the Kentucky shoreline, as well as farmland and fruit groves that could provide sources of income. From there the family could raise a lantern on a flagpole to signal fleeing slaves in Kentucky when it was safe for them to cross the Ohio River.http://dbs.ohiohistory.org/africanam/page.cfm?ID=4626 Rankin also constructed a staircase leading up the hill to the house for slaves to climb up to safety on their way further north.http://dbs.ohiohistory.org/africanam/page.cfm?ID=4630 For over forty years leading up to the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, many of the 2000 slaves who escaped to freedom through Ripley stayed at the family's home, and none was ever recaptured there. It became known as the Rankin House and is now a U.S. National historic landmark

National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

(see photos).

The real Eliza

During a visit by Rankin to Lane Theological Seminary to see one of his sons, he told Professor Calvin StoweCalvin Ellis Stowe

thumb|Calvin Ellis Stowe, circa 1850Calvin Ellis Stowe was an American Biblical scholar who helped spread public education in the United States, and the husband and literary agent of Harriet Beecher Stowe.-Life and career:...

the story of a woman the Rankins had housed in 1838 after she escaped by crossing the frozen Ohio River with her child in her arms. Stowe's wife (Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe was an American abolitionist and author. Her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was a depiction of life for African-Americans under slavery; it reached millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and United Kingdom...

) also heard the account and later modeled the character Eliza in her book Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman....

after the woman.

Film depiction

The film, "Brothers of the Borderland," is a permanent feature of the National Underground Railroad Freedom CenterNational Underground Railroad Freedom Center

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is a museum in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio based on the history of the Underground Railroad. The Center also pays tribute to all efforts to "abolish human enslavement and secure freedom for all people." Billed as part of a new group of "museums of...

in Cincinnati (opened 2004) that depicts Rankin's work in the Underground Railroad in Ripley.

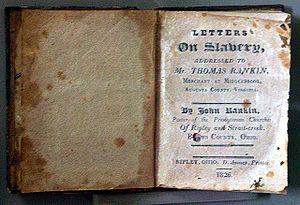

Letters on Slavery

Augusta County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 65,615 people, 24,818 households, and 18,911 families residing in the county. The population density was 68 people per square mile . There were 26,738 housing units at an average density of 28 per square mile...

, Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, had purchased slaves. He was provoked to write a series of anti-slavery letters to his brother that were published by the editor of the local Ripley newspaper The Castigator. When the letters were published in book form in 1826 as Letters on Slavery, they provided one of the first clearly articulated anti-slavery views printed west of the Appalachians. Thomas Rankin, convinced by his brother's words, moved to Ohio in 1827 and freed his slaves. By the 1830s, Letters on Slavery had become standard reading for abolitionists all over the United States. In 1832, William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

printed them in his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison later called Rankin his "anti-slavery father," saying that "his book on slavery was the cause of my entering the anti-slavery conflict."

Beyond the pulpit

In 1833 Rankin came to know Theodore WeldTheodore Dwight Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld , was one of the leading architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years, from 1830 through 1844.Weld played a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer...

through their involvement with the creation of the American Anti-Slavery Society

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass was a key leader of this society and often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown was another freed slave who often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had...

. Weld had come to Ohio from Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

to attend Lane Theological Seminary

Lane Theological Seminary

Lane Theological Seminary was established in the Walnut Hills section of Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1829 to educate Presbyterian ministers. It was named in honor of Ebenezer and William Lane, who pledged $4,000 for the new school, which was seen as a forward outpost of the Presbyterian Church in the...

in Cincinnati

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

. In November 1834 at Rankin's Ripley church, Weld began a year-long series of speeches throughout Ohio that raised the profile of the abolitionist movement in the state and inspired Rankin to also expand his work beyond the pulpit and beyond Ripley, speaking from town to town on behalf of the national Society and founding many new local societies.

While in Zanesville, Ohio

Zanesville, Ohio

Zanesville is a city in and the county seat of Muskingum County, Ohio, United States. The population was 25,586 at the 2000 census.Zanesville was named after Ebenezer Zane, who had constructed Zane's Trace, a pioneer road through present-day Ohio...

, for the formation of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, Rankin had his first real experience with mob opposition to his efforts as he was showered with rotten eggs in town. When he stopped in Chillicothe

Chillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe is a city in and the county seat of Ross County, Ohio, United States.Chillicothe was the first and third capital of Ohio and is located in southern Ohio along the Scioto River. The name comes from the Shawnee name Chalahgawtha, meaning "principal town", as it was a major settlement of...

to speak at a church on the way home, stones were thrown through the window.

In 1836, Weld invited Rankin to join a group called "the Seventy" who were selected by the American Anti-Slavery Society to travel to churches throughout the Northern states preaching in support of immediate emancipation and forming local anti-slavery societies. Released by his congregation for one year to participate in the effort, Rankin's passion for the cause grew with the opposition to his "dangerous" views, even among many who opposed slavery but feared the instigation of a slave uprising. A bounty of up to $3000 was placed on his life, and in 1841 he and his sons had to fight off attackers who came to burn his house and barn in the middle of the night.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Law or Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern slave holding interests and Northern Free-Soilers. This was one of the most controversial acts of the 1850 compromise and heightened...

heightened the danger and profile of their assistance to runaways as it had become illegal to do so, even in free states. At an anti-slavery society meeting in Highland County, Ohio

Highland County, Ohio

As of the census of 2000, there were 40,875 people, 15,587 households, and 11,394 families residing in the county. The population density was 74 people per square mile . There were 17,583 housing units at an average density of 32 per square mile...

held by Rankin and Salmon P. Chase

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase was an American politician and jurist who served as U.S. Senator from Ohio and the 23rd Governor of Ohio; as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Abraham Lincoln; and as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.Chase was one of the most prominent members...

, however, Rankin declared, "Disobedience to the enactment is obedience to God."

Opposition within his own congregation, spurred by Rankin's attempts to expel slaveowners from the church, finally led him to resign in 1846 after 24 years as minister of the Ripley Presbyterian Church. Over one-third of the church's members left with him and helped Rankin establish the Free Presbyterian Church, which grew to have 72 congregations.

"Freedom's Heroes"

In May 1892, six years after John Rankin's death, a monument aptly named "Freedom's Heroes,", was dedicated to Rankin and his wife, Jean Lowry RankinJean Lowry Rankin

Jean Lowry Rankin was an American was an Abolitionist and pioneer in the anti-slavery movement. With her husband John Rankin she assisted 2000 slaves in their journey to freedom along the Underground Railroad...

, on the grounds of the Maplewood Cemetery in Ripley, Ohio.

External links

- John Rankin, a committed abolitionist! The African American Registry

- John Rankin. Ohio History Central

- Aboard the Underground Railroad -- John Rankin House. National Park Service Cultural Resources

- The Rankin House. Ohio Historical Society

- The Rankin House. Ripley, Ohio: Freedom's Landing

- Borderlander of Light: Rev. Rankin and Ripley, Ohio. Donna B. Jacobson: University of Connecticut