Kanbun

Encyclopedia

The Japanese word originally meant "Classical Chinese

writings, Chinese classic texts

, Classical Chinese literature

". This evolved into a Japanese method of reading annotated Classical Chinese in translation (c.f. interlinear gloss for European tradition). Much Japanese literature

was written in literary Chinese using this annotated style. As this was the general writing style for official and intellectual works for many centuries, Sino-Japanese vocabulary makes up a large portion of the modern Japanese language

lexicon, and much old Chinese literature is accessible to Japanese readers in some semblance of the original.

originated through adoption and adaptation of Written Chinese. Japan's oldest books (e.g., Kojiki

and Nihon Shoki

) and dictionaries (e.g., Tenrei Banshō Meigi

and Wamyō Ruijushō

) were written in kanji and kanbun. Other Japanese literary genres have parallels; the Kaifūsō

is the oldest collection of "Chinese poetry composed by Japanese poets". Burton Watson

's (1975, 1976) English translations of kanbun compositions provide a good introduction to this literary field.

Roy Andrew Miller

notes that although Japanese kanbun conventions have Sinoxenic

parallels with other traditions for reading Classical Chinese like Korean

hanmun and Vietnamese

Hán Văn , only kanbun has survived into the present day. He explains how

William C. Hannas points out the linguistic hurdles involved in kanbun transformation.

He lists four major Japanese problems: word order

, parsing which Chinese characters should be read together, deciding how to pronounce the characters, and finding suitable equivalents for Chinese function words.

According to John Timothy Wixted, scholars have disregarded kanbun.

A promising new development in kanbun studies is the Web-accessible database being developed by scholars at Nishōgakusha University in Tokyo (see Kamichi and Machi 2006).

Kanbun implemented two particular types of kana: , "kana suffixes added to kanji stems to show their Japanese readings" and , "smaller kana syllables printed/written alongside kanji to indicate pronunciation".

Kanbun – as opposed to meaning "Japanese text, composition written with Japanese syntax and predominately kun'yomi readings" – is subdivided into several types. "Chinese text, composition written with Chinese syntax and on'yomi Chinese characters" "unpunctuated kanbun text without reading aids" "Sino-Japanese composition written with Japanese syntax and mixed on'yomi and kun'yomi readings" "Chinese modified with Japanese syntax; a Japanized version of classical Chinese"

Jean-Noël Robert describes kanbun as a "perfectly frozen, 'dead,' language" that was continuously used from the late Heian Period

until after World War II.

Inasmuch as Classical Chinese was originally unpunctuated, the kanbun tradition developed various conventional reading punctuation, diacritical, and syntactic markers. "guiding marks for rendering Chinese into Japanese" "the Japanese reading/pronunciation of a kanji character" "a Japanese reading of a Chinese passage" "diacritical dots on characters to indicate Japanese grammatical inflections" "punctuation marks (e.g., 、comma and 。 period)" "marks placed alongside characters indicating their Japanese ordering is to be 'returned' (read in reverse)"

Kaeriten grammatically transform Classical Chinese into Japanese word order. Two are syntactic symbols, the | "linking mark" denotes phrases and the denotes "return/reverse marks". The rest are kanji commonly used in numbering and ordering systems: 4 numerals ichi "one", ni "two", san "three", and yon "four"; 3 locatives ue "top" , naka 中 "middle", and shita "bottom"; 4 Heavenly Stems kinoe "first", kinoto "second", hinoe "third", and hinoto "fourth"; and the 3 cosmological ten "heaven", chi "earth", and jin "person". For written English, these kaeriten would correspond with 1, 2, 3; I, II, III; A, B, C, etc.

As an analogy for how kanbun numerically marks Chinese sentences with subject–verb–object (SVO) word order into Japanese subject–object–verb (SOV), John DeFrancis

(1989:132) gives this English (another SVO language) literal translation of the Latin (another SOV) Commentarii de Bello Gallico

opening.

Two English textbooks for students of kanbun are by Crawcour (1965, reviewed by Ury 1990; available for download here: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/p/pod/dod-idx?c=cjs;idno=akz7043.0001.001) and Komai and Rohlich (1988, reviewed by Markus 1990 and Wixted 1998).

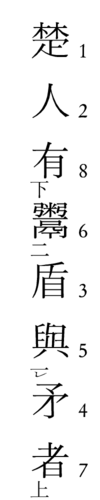

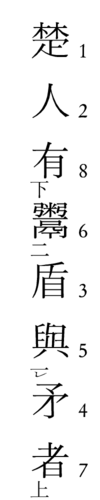

The illustration to the right exemplifies kanbun. These eight characters are the well-known first line in the Han Feizi

The illustration to the right exemplifies kanbun. These eight characters are the well-known first line in the Han Feizi

story (chap. 36, 難一 "Collection of Difficulties, No. 1") that first recorded the word máodùn (Japanese mujun, 矛盾 "contradiction, inconsistency", lit. "spear-shield"), illustrating the irresistible force paradox

. In debating with a Confucianist about the legendary Chinese sage rulers Yao

and Shun, Legalist

Master Han Fei argues that you cannot praise them both because you would be making a "spear-shield" contradiction. The context, in a word-for-word English translation, reads:

Since Chinese and English both have subject–verb–object grammatical order, literally translating this first sentence is straightforwardly understandable, excepting the final particle zhě 者 "one who; that which", which is a nominalizer that marks a pause after a noun phrase

.

The original Chinese sentence is marked with five Japanese kaeriten as:

To interpret this, the character 有 "was" marked with shita 下 "bottom" is shifted to the location marked by ue 上 "top", and likewise the character 鬻 "sell" marked with ni 二 "two" is shifted to the location marked by ichi 一 "one". The re レ "reverse mark" indicates that the order of the adjacent characters must be reversed. Or, to represent this kanbun reading in numerical terms:

Following these kanbun instructions step by step transforms the sentence into Japanese subject–object–verb grammatical order. The Sino-Japanese on'yomi readings and meanings are:

Next, Japanese function words and conjugations can be added with okurigana, and Japanese to ... to と...と "and" can be substituted for Chinese 與 "and", specifically, the first と is treated as the reading of 與, and the second, an additional function word:

Lastly, kun'yomi readings for characters can be annotated with furigana. This practice, which is commonly provided in texts intended for Japanese children and students, would be unnecessary for educated native speakers. This sentence's only uncommon kanji is hisa(gu) 鬻ぐ "sell, deal in", a literary character which neither Kyōiku kanji

nor Jōyō kanji

includes.

The completed kundoku translation with kun'yomi reads as a well-formed Japanese sentence:

Coming full circle, this annotated Japanese kanbun example back-translates: "There is a man from Chu who was selling shields and spears," or more idiomatically, "There was a man from Chu who was selling shields and spears."

Standard in June, 1993 with the release of version 1.1.

Alan Wood (linked below) says: "The Japanese word kanbun refers to classical Chinese writing as used in Japan. The characters in this range are used to indicate the order in which words should be read in these Chinese texts."

Two Unicode kaeriten are grammatical symbols (㆐㆑) for "linking marks" and "reverse marks". The others are organizational kanji for: numbers (㆒㆓㆔㆕) "1, 2, 3, 4"; locatives (㆖㆗㆘) "top, middle, bottom"; Heavenly Stems (㆙㆚㆛㆜) "1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th"; and levels (㆝㆞㆟) "heaven, earth, person".

The Unicode block for kanbun is U+3190–U+319F:

Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese or Literary Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese based on the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Chinese, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese...

writings, Chinese classic texts

Chinese classic texts

Chinese classic texts, or Chinese canonical texts, today often refer to the pre-Qin Chinese texts, especially the Neo-Confucian titles of Four Books and Five Classics , a selection of short books and chapters from the voluminous collection called the Thirteen Classics. All of these pre-Qin texts...

, Classical Chinese literature

Chinese literature

Chinese literature extends thousands of years, from the earliest recorded dynastic court archives to the mature fictional novels that arose during the Ming Dynasty to entertain the masses of literate Chinese...

". This evolved into a Japanese method of reading annotated Classical Chinese in translation (c.f. interlinear gloss for European tradition). Much Japanese literature

Japanese literature

Early works of Japanese literature were heavily influenced by cultural contact with China and Chinese literature, often written in Classical Chinese. Indian literature also had an influence through the diffusion of Buddhism in Japan...

was written in literary Chinese using this annotated style. As this was the general writing style for official and intellectual works for many centuries, Sino-Japanese vocabulary makes up a large portion of the modern Japanese language

Japanese language

is a language spoken by over 130 million people in Japan and in Japanese emigrant communities. It is a member of the Japonic language family, which has a number of proposed relationships with other languages, none of which has gained wide acceptance among historical linguists .Japanese is an...

lexicon, and much old Chinese literature is accessible to Japanese readers in some semblance of the original.

History

The Japanese writing systemJapanese writing system

The modern Japanese writing system uses three main scripts:*Kanji, adopted Chinese characters*Kana, a pair of syllabaries , consisting of:...

originated through adoption and adaptation of Written Chinese. Japan's oldest books (e.g., Kojiki

Kojiki

is the oldest extant chronicle in Japan, dating from the early 8th century and composed by Ō no Yasumaro at the request of Empress Gemmei. The Kojiki is a collection of myths concerning the origin of the four home islands of Japan, and the Kami...

and Nihon Shoki

Nihon Shoki

The , sometimes translated as The Chronicles of Japan, is the second oldest book of classical Japanese history. It is more elaborate and detailed than the Kojiki, the oldest, and has proven to be an important tool for historians and archaeologists as it includes the most complete extant historical...

) and dictionaries (e.g., Tenrei Banshō Meigi

Tenrei Bansho Meigi

The is the oldest extant Japanese dictionary of Chinese characters. The title is also written 篆隷万象名義 with the modern graphic variant ban for ban ....

and Wamyō Ruijushō

Wamyo Ruijusho

The is a 938 CE Japanese dictionary of Chinese characters. The Heian Period scholar Minamoto no Shitagō began compilation in 934, at the request of Emperor Daigo's daughter...

) were written in kanji and kanbun. Other Japanese literary genres have parallels; the Kaifūsō

Kaifuso

is the oldest collection of Chinese poetry written by Japanese poets.It was created by an unknown compiler in 751. In the brief introductions of the poets, the unknown writer seems sympathic to Emperor Kōbun and his regents who were overthrown in 672 by Emperor Temmu after only eight months of the...

is the oldest collection of "Chinese poetry composed by Japanese poets". Burton Watson

Burton Watson

Burton Watson is an accomplished translator of Chinese and Japanese literature and poetry. He has received awards including the Gold Medal Award of the Translation Center at Columbia University in 1979, the PEN Translation Prize in 1981 for his translation with Hiroaki Sato of From the Country of...

's (1975, 1976) English translations of kanbun compositions provide a good introduction to this literary field.

Roy Andrew Miller

Roy Andrew Miller

Roy Andrew Miller is a linguist notable for his advocacy of Korean and Japanese as members of the Altaic group of languages....

notes that although Japanese kanbun conventions have Sinoxenic

Sinoxenic

Sino-Xenic refers to the pronunciations given to Chinese characters in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese – none of which have accepted genetic relatedness to Sinitic languages – in the Sino-Japanese, Sino-Korean, and Sino-Vietnamese vocabularies...

parallels with other traditions for reading Classical Chinese like Korean

Korean language

Korean is the official language of the country Korea, in both South and North. It is also one of the two official languages in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in People's Republic of China. There are about 78 million Korean speakers worldwide. In the 15th century, a national writing...

hanmun and Vietnamese

Vietnamese language

Vietnamese is the national and official language of Vietnam. It is the mother tongue of 86% of Vietnam's population, and of about three million overseas Vietnamese. It is also spoken as a second language by many ethnic minorities of Vietnam...

Hán Văn , only kanbun has survived into the present day. He explains how

in the Japanese kanbun reading tradition a Chinese text is simultaneously punctuated, analyzed, and translated into classical Japanese. It operates according to a limited canon of Japanese forms and syntactic structures which are treated as existing in a one-to-one alignment with the vocabulary and structures of classical Chinese. At its worst, this system for reading Chinese as if it were Japanese became a kind of lazy schoolboy's trot to a classical text; at its best, it has preserved the analysis and interpretation of large body of literary Chinese texts which would otherwise have been completely lost; hence, the kanbun tradition can often be of great value for an understanding of early Chinese literature. (1967:31)

William C. Hannas points out the linguistic hurdles involved in kanbun transformation.

Kambun, literally "Chinese writing," refers to a genre of techniques for making Chinese texts read like Japanese, or for writing in a way imitative of Chinese. For a Japanese, neither of these tasks could be accomplished easily because of the two languages' different structures. As I have mentioned, Chinese is an isolating languageIsolating languageAn isolating language is a type of language with a low morpheme-per-word ratio — in the extreme case of an isolating language words are composed of a single morpheme...

. Its grammatical relations are identified in subject–verb–object (SVO) order and through the use of particlesGrammatical particleIn grammar, a particle is a function word that does not belong to any of the inflected grammatical word classes . It is a catch-all term for a heterogeneous set of words and terms that lack a precise lexical definition...

similar to English prepositions. Inflection plays no role in the grammar. Morphemes are typically one syllable in length and combine to form words without modification to their phonetic structures (tone excepted). Conversely, the basic structure of a transitive Japanese sentence is SOV, with the usual syntactic features associated with languages of this typology, including postpositions, that is, grammar particles that appear after the words and phrases to which they apply. (1997:32)

He lists four major Japanese problems: word order

Word order

In linguistics, word order typology refers to the study of the order of the syntactic constituents of a language, and how different languages can employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic subdomains are also of interest...

, parsing which Chinese characters should be read together, deciding how to pronounce the characters, and finding suitable equivalents for Chinese function words.

According to John Timothy Wixted, scholars have disregarded kanbun.

In terms of its size, often its quality, and certainly its importance both at the time it was written and cumulatively in the cultural tradition, kanbun is arguably the biggest and most important area of Japanese literary study that has been ignored in recent times, and the one least properly represented as part of the canon. (1998:23)

A promising new development in kanbun studies is the Web-accessible database being developed by scholars at Nishōgakusha University in Tokyo (see Kamichi and Machi 2006).

Conventions and terminology

Compositions written in kanbun used two common types of Japanese readings: Sino-Japanese on'yomi (音読み "pronunciation readings") borrowed from Chinese pronunciations and native Japanese from Japanese equivalents. For example, can be read as dō adapted from Middle Chinese /dấw/ or as michi from the indigenous Japanese word meaning "road, street".Kanbun implemented two particular types of kana: , "kana suffixes added to kanji stems to show their Japanese readings" and , "smaller kana syllables printed/written alongside kanji to indicate pronunciation".

Kanbun – as opposed to meaning "Japanese text, composition written with Japanese syntax and predominately kun'yomi readings" – is subdivided into several types. "Chinese text, composition written with Chinese syntax and on'yomi Chinese characters" "unpunctuated kanbun text without reading aids" "Sino-Japanese composition written with Japanese syntax and mixed on'yomi and kun'yomi readings" "Chinese modified with Japanese syntax; a Japanized version of classical Chinese"

Jean-Noël Robert describes kanbun as a "perfectly frozen, 'dead,' language" that was continuously used from the late Heian Period

Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. The period is named after the capital city of Heian-kyō, or modern Kyōto. It is the period in Japanese history when Buddhism, Taoism and other Chinese influences were at their height...

until after World War II.

Classical Chinese, which, as we have seen, had long since ceased to be a spoken language on the mainland (if indeed it had ever had been), has been in use in the Japanese archipelago longer than the Japanese language itself. The oldest written remnants found in Japan are all in Chinese, though it is a matter of considerable debate whether traces of the Japanese vernacular are to be found in them. Taking both languages together until the end of the nineteenth century, and taking into account all the monastic documents, literature in the widest sense of the term, and texts in "near-Chinese" (hentai-kanbun), it is entirely possible that the sheer volume of texts written in Chinese in Japan slightly exceed what was written in Japanese. (2006:32)

Inasmuch as Classical Chinese was originally unpunctuated, the kanbun tradition developed various conventional reading punctuation, diacritical, and syntactic markers. "guiding marks for rendering Chinese into Japanese" "the Japanese reading/pronunciation of a kanji character" "a Japanese reading of a Chinese passage" "diacritical dots on characters to indicate Japanese grammatical inflections" "punctuation marks (e.g., 、comma and 。 period)" "marks placed alongside characters indicating their Japanese ordering is to be 'returned' (read in reverse)"

Kaeriten grammatically transform Classical Chinese into Japanese word order. Two are syntactic symbols, the | "linking mark" denotes phrases and the denotes "return/reverse marks". The rest are kanji commonly used in numbering and ordering systems: 4 numerals ichi "one", ni "two", san "three", and yon "four"; 3 locatives ue "top" , naka 中 "middle", and shita "bottom"; 4 Heavenly Stems kinoe "first", kinoto "second", hinoe "third", and hinoto "fourth"; and the 3 cosmological ten "heaven", chi "earth", and jin "person". For written English, these kaeriten would correspond with 1, 2, 3; I, II, III; A, B, C, etc.

As an analogy for how kanbun numerically marks Chinese sentences with subject–verb–object (SVO) word order into Japanese subject–object–verb (SOV), John DeFrancis

John DeFrancis

John DeFrancis was an American linguist, sinologist, author of Chinese language textbooks, lexicographer of Chinese dictionaries, and Professor Emeritus of Chinese Studies at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa....

(1989:132) gives this English (another SVO language) literal translation of the Latin (another SOV) Commentarii de Bello Gallico

Commentarii de Bello Gallico

Commentarii de Bello Gallico is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Caesar describes the battles and intrigues that took place in the nine years he spent fighting local armies in Gaul that opposed Roman domination.The "Gaul" that Caesar...

opening.

| Gallia | est | omnis | divisa | in | partes | tres |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Gaul | is | all | divided | into | parts | three |

Two English textbooks for students of kanbun are by Crawcour (1965, reviewed by Ury 1990; available for download here: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/p/pod/dod-idx?c=cjs;idno=akz7043.0001.001) and Komai and Rohlich (1988, reviewed by Markus 1990 and Wixted 1998).

Example

Han Feizi (book)

The Han Feizi is a work written by Han Feizi at the end of the Warring States Period in China, detailing his political philosophy. It belongs to the Legalist school of thought....

story (chap. 36, 難一 "Collection of Difficulties, No. 1") that first recorded the word máodùn (Japanese mujun, 矛盾 "contradiction, inconsistency", lit. "spear-shield"), illustrating the irresistible force paradox

Irresistible force paradox

The Irresistible force paradox, also the unstoppable force paradox, is a classic paradox formulated as "What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?" This paradox is a form of the omnipotence paradox, which is a simple demonstration that challenges omnipotence:...

. In debating with a Confucianist about the legendary Chinese sage rulers Yao

Yao (ruler)

Yao , was a legendary Chinese ruler, one of the Three Sovereigns and the Five Emperors. His ancestral name (姓)is Yi Qi (伊祁) or Qi(祁),clan name (氏)is Taotang , given name is Fangxun , as the second son to Emperor Ku and Qingdu...

and Shun, Legalist

Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

In Chinese history, Legalism was one of the main philosophic currents during the Warring States Period, although the term itself was invented in the Han Dynasty and thus does not refer to an organized 'school' of thought....

Master Han Fei argues that you cannot praise them both because you would be making a "spear-shield" contradiction. The context, in a word-for-word English translation, reads:

A-man from-Ch'u was-selling spears and shields. Praising them, he-said: My shields are so-hard-that [of all] things none can defeat-them. Again, praising his spears, he-said: My spears are so-sharp-that [of all] things none can defeat-them. Someone said: What if with your spear [I were to] defeat your shield? That man was not able-to respond." (tr. Wu 1997:111)

Since Chinese and English both have subject–verb–object grammatical order, literally translating this first sentence is straightforwardly understandable, excepting the final particle zhě 者 "one who; that which", which is a nominalizer that marks a pause after a noun phrase

Noun phrase

In grammar, a noun phrase, nominal phrase, or nominal group is a phrase based on a noun, pronoun, or other noun-like word optionally accompanied by modifiers such as adjectives....

.

| 楚 | 人 | 有 | 鬻 | 盾 | 與 | 矛 | 者 |

| Chǔ | rén | yǒu | yù | dùn | yǔ | máo | zhě |

| Chu | man | was | selling | shields | and | spears | (nominalizer) |

The original Chinese sentence is marked with five Japanese kaeriten as:

- 楚人有下鬻二盾與一レ矛者上

To interpret this, the character 有 "was" marked with shita 下 "bottom" is shifted to the location marked by ue 上 "top", and likewise the character 鬻 "sell" marked with ni 二 "two" is shifted to the location marked by ichi 一 "one". The re レ "reverse mark" indicates that the order of the adjacent characters must be reversed. Or, to represent this kanbun reading in numerical terms:

| 楚 | 人 | 有 | 鬻 | 盾 | 與 | 矛 | 者 |

| 1 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

Following these kanbun instructions step by step transforms the sentence into Japanese subject–object–verb grammatical order. The Sino-Japanese on'yomi readings and meanings are:

| 楚 | 人 | 盾 | 矛 | 與 | 鬻 | 者 | 有 |

| So | jin | jun | mu | yo | iku | sha | yū |

| Chu | man | shields | spears | and | sell | (nominalizer) | was |

Next, Japanese function words and conjugations can be added with okurigana, and Japanese to ... to と...と "and" can be substituted for Chinese 與 "and", specifically, the first と is treated as the reading of 與, and the second, an additional function word:

- 楚人に盾と矛とを鬻ぐ者有り

Lastly, kun'yomi readings for characters can be annotated with furigana. This practice, which is commonly provided in texts intended for Japanese children and students, would be unnecessary for educated native speakers. This sentence's only uncommon kanji is hisa(gu) 鬻ぐ "sell, deal in", a literary character which neither Kyōiku kanji

Kyoiku kanji

, also known as is a list of 1,006 kanji and associated readings developed and maintained by the Japanese Ministry of Education that prescribes which kanji, and which readings of kanji, Japanese schoolchildren should learn for each year of primary school...

nor Jōyō kanji

Joyo kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current jōyō kanji are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010...

includes.

The completed kundoku translation with kun'yomi reads as a well-formed Japanese sentence:

| 楚 | 人 | に | 盾 | と | 矛 | と | を | 鬻 | ぐ | 者 | 有 | り |

| So | hito | ni | tate | to | hoko | to | o | hisa | gu | mono | a | ri |

| Chu | people | among | shields | and | spears | and | (directobject) | sell- | ing | man | exist- | s |

Coming full circle, this annotated Japanese kanbun example back-translates: "There is a man from Chu who was selling shields and spears," or more idiomatically, "There was a man from Chu who was selling shields and spears."

Unicode

Kanbun were added to the UnicodeUnicode

Unicode is a computing industry standard for the consistent encoding, representation and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems...

Standard in June, 1993 with the release of version 1.1.

Alan Wood (linked below) says: "The Japanese word kanbun refers to classical Chinese writing as used in Japan. The characters in this range are used to indicate the order in which words should be read in these Chinese texts."

Two Unicode kaeriten are grammatical symbols (㆐㆑) for "linking marks" and "reverse marks". The others are organizational kanji for: numbers (㆒㆓㆔㆕) "1, 2, 3, 4"; locatives (㆖㆗㆘) "top, middle, bottom"; Heavenly Stems (㆙㆚㆛㆜) "1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th"; and levels (㆝㆞㆟) "heaven, earth, person".

The Unicode block for kanbun is U+3190–U+319F:

External links

- Kanbun in Unicode

- Kanbun – Test for Unicode support in Web browsers, Alan Wood日本漢文学研究の世界的拠点の構築 Establishment of World Organization for Kanbun Studies, Nishōgakusha University