Katana

Encyclopedia

A Japanese sword, or , is one of the traditional bladed weapons (nihonto) of Japan

. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.

, which is a single-edged and usually curved long sword traditionally worn by samurai

from the 15th century onwards. Other types of Japanese swords include: tsurugi

or ken, which is a double-edged sword; ōdachi

, nodachi

, tachi

, which are older styles of a very long single-edged sword; wakizashi

, a medium sized sword; and the tanto

which is an even smaller knife sized sword . Although they are pole-mounted weapons, the naginata

and yari

are considered part of the nihontō family due to the methods by which they are forged.

Japanese swords are still commonly seen today; antique and modernly-forged swords can easily be found and purchased. Modern, authentic nihontō are made by a few hundred swordsmiths. Many examples can be seen at an annual competition hosted by the All Japan Swordsmith Association, under the auspices of the Nihontō Bunka Shinkō Kyōkai (Society for the promotion of Japanese Sword Culture).

poet Ouyang Xiu

. The word nihontō became more common in Japan in the late Tokugawa shogunate

. Due to importation of Western swords, the word nihontō was adopted in order to distinguish it from the .

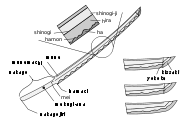

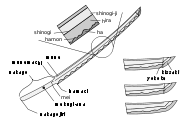

Each blade has a unique profile, mostly dependent on the swordsmith and the construction method. The most prominent part is the middle ridge, or shinogi. In the earlier picture, the examples were flat to the shinogi, then tapering to the blade. However, swords could narrow down to the shinogi, then narrow further to the blade, or even expand outward towards the shinogi then shrink to the blade (producing a trapezoidal shape). A flat or narrowing shinogi is called shinogi-hikushi, whereas a fat blade is called a shinogi-takushi.

Each blade has a unique profile, mostly dependent on the swordsmith and the construction method. The most prominent part is the middle ridge, or shinogi. In the earlier picture, the examples were flat to the shinogi, then tapering to the blade. However, swords could narrow down to the shinogi, then narrow further to the blade, or even expand outward towards the shinogi then shrink to the blade (producing a trapezoidal shape). A flat or narrowing shinogi is called shinogi-hikushi, whereas a fat blade is called a shinogi-takushi.

The shinogi can be placed near the back of the blade for a longer, sharper, more fragile tip or a more moderate shinogi near the center of the blade.

The sword also has an exact tip shape, which is considered an extremely important characteristic: the tip can be long (ōkissaki), medium (chūkissaki), short (kokissaki), or even hooked backwards (ikuri-ōkissaki). In addition, whether the front edge of the tip is more curved (fukura-tsuku) or (relatively) straight (fukura-kareru) is also important.

The kissaki (point) is not a "chisel-like" point, nor is the Western knife interpretation of a "tanto point" found on true Japanese swords; a straight, linearly-sloped point has the advantage of being easy to grind, but it bears only a superficial similarity to traditional Japanese kissaki. Kissaki have a curved profile, and smooth three-dimensional curvature across their surface towards the edge - though they are bounded by a straight line called the yokote and have crisp definition at all their edges.

Although it is not commonly known, the "chisel point" kissaki originated in Japan. Examples of such are shown in the book "The Japanese Sword" by Kanzan Sato. Because American bladesmiths use this design extensively it is a common misconception that the design originated in America.

A hole is punched through the tang nakago, called a mekugi-ana. It is used to anchor the blade using a mekugi, a small bamboo pin that is inserted into another cavity in the handle tsuka and through the mekugi-ana, thus restricting the blade from slipping out. To remove the tsuka one removes the mekugi. The swordsmith's signature mei is placed on the nakago.

— was called the tsuba. Other aspects of the mountings (koshirae), such as the menuki (decorative grip swells), habaki (blade collar and scabbard wedge), fuchi and kashira (handle collar and cap), kozuka (small utility knife handle), kogai (decorative skewer-like implement), saya lacquer, and tsuka-ito (professional handle wrap, also named tsukamaki), received similar levels of artistry.

What generally differentiates the different swords is their length. Japanese swords are measured in units of shaku. Since 1891, the modern Japanese 'shaku' is approximately equal to a foot (11.93 inches), calibrated with the meter to equal exactly 10 meters per 33 shaku (30.30 cm).

What generally differentiates the different swords is their length. Japanese swords are measured in units of shaku. Since 1891, the modern Japanese 'shaku' is approximately equal to a foot (11.93 inches), calibrated with the meter to equal exactly 10 meters per 33 shaku (30.30 cm).

However the historical shaku was slightly longer (13.96 inches or 35.45 cm). Thus, there may sometimes be confusion about the blade lengths, depending on which shaku value is being assumed when converting to metric or US measurements.

The three main divisions of Japanese blade length are:

A blade shorter than one shaku is considered a tantō (knife). A blade longer than one shaku but less than two is considered a shōtō (short sword). The wakizashi and kodachi

are in this category. The length is measured in a straight line across the back of the blade from tip to munemachi (where blade meets tang

). Most blades that fall into the "shōtō" size range are wakizashi

. However, some daitō were designed with blades slightly shorter than 2 shaku. These were called kodachi

and are somewhere in between a true daitō and a wakizashi. A shōtō and a daitō together are called a daishō

(literally, "big and small"). The daishō was the symbolic armament of the Edo period

samurai

.

A blade longer than two shaku is considered a daitō, or long sword. To qualify as a daitō the sword must have a blade longer than 2 shaku (approximately 24 inches or 60 centimeters) in a straight line. While there is a well defined lower-limit to the length of a daitō, the upper limit is not well enforced; a number of modern historians, swordsmiths, etc. say that swords that are over 3 shaku in blade length are "longer than normal daitō" and are usually referred to or called ōdachi

. The word "daitō" is often used when explaining the related terms shōtō (short sword) and daishō

(the set of both large and small sword). Miyamoto Musashi

refers to the long sword in The Book of Five Rings. He is referring to the katana in this, and refers to the nodachi and the odachi as "extra-long swords".

Before 1500 most swords were usually worn suspended from cords on a belt, edge-down. This style is called jindachi-zukuri, and daitō worn in this fashion are called tachi (average blade length of 75–80 cm). From 1600 to 1867, more swords were worn through an obi

(sash), paired with a smaller blade; both worn edge-up. This style is called buke-zukuri, and all daitō worn in this fashion are katana, averaging 70–74 cm (2 shaku 3 sun to 2 shaku 4 sun 5 bu) in blade length. However, nihontō of longer lengths also existed, including lengths up to 78 cm (2 shaku 5 sun 5 bu).

The weight of a nihontō rarely exceeded 1 kg without the saya.

It was not simply that the swords were worn by cords on a belt, as a 'style' of sorts. Such a statement trivializes an important function of such a manner of bearing the sword. It was a very direct example of 'form following function.' At this point in Japanese history, much of the warfare was fought on horseback. Being so, if the sword/blade were in a more vertical position, it would be cumbersome, and awkward to draw. Suspending the sword by 'cords,' allowed the sheath to be more horizontal, and far less likely to bind while drawing it in that position.

A is simply a shorter nihontō. It is longer than the wakizashi, usually about 18 inches in length. The most common reference to a chisa katana is a shorter nihontō that does not have a companion blade. They were most commonly made in the buke-zukuri mounting.

Abnormally long blades (longer than 3 shaku), usually carried across the back, are called ōdachi

or nodachi

. The word ōdachi is also sometimes used as a synonym for nihontō. Odachi means "Great Sword", and Nodachi translates to "Field sword". Nodachi were used during war as the longer sword gave a foot soldier a reach advantage, but now nodachi are illegal because of their effectiveness as a killing weapon. Citizens are not allowed to possess an odachi unless it is for ceremonial purposes.

Here is a list of lengths for different types of swords:

Swords whose length is next to a different classification type are described with a prefix 'O-' (for great) or 'Ko-' (for small), e.g. a Wakizashi with a length of 59 cm is called a O-wakizashi (almost a Katana) whereas a Katana with 61 cm is called a Ko-Katana (for small Katana) .

Since 1867, restrictions and/or the deconstruction of the samurai class meant that most blades have been worn jindachi-zukuri style, like Western navy officers. Since 1953, there has been a resurgence in the buke-zukuri style, permitted only for demonstration purposes. Swords designed specifically to be tachi are generally kotō rather than shintō, so they are generally better manufactured and more elaborately decorated, however, these are still katana if worn in modern buke-zukuri style.

In the Kotō era there were several other schools that did not fit within the Gokaden or were known to mix elements of each Gokaden, and they were called wakimono (small school). There were 19 commonly referenced wakimono.

Before 987, examples of Japanese swords were straight chokutō

Before 987, examples of Japanese swords were straight chokutō

or jōkotō and others with unusual shapes. In the Heian period

(8th to 11th centuries) sword-making developed through techniques brought over from China

through trade in the early 10th century during the Tang Dynasty

and through Siberia

and Hokkaidō

, territory of the Ainu people

. The Ainu used and these influenced the nihontō, which was held with two hands and designed for cutting, rather than stabbing. According to legend, the Japanese sword was invented by a smith named Amakuni

(ca.700 AD), along with the folded steel process. The folded steel process and single edge swords had been invented in the early 10th century Japan. Swords forged between 987 and 1597 are called (lit., "old swords"); these are considered the pinnacle of Japanese swordcraft. Early models had uneven curves with the deepest part of the curve at the hilt

. As eras changed the center of the curve tended to move up the blade.

The nihonto as we know it today with its deep, graceful curve has its origin in shinogi-zukuri (single-edged blade with ridgeline) tachi

which were developed sometime around the middle of the Heian period to service the need of the growing military class. Its shape reflects the changing form of warfare in Japan. Cavalry were now the predominant fighting unit and the older straight chokutō were particularly unsuitable for fighting from horseback. The curved sword is a far more efficient weapon when wielded by a warrior on horseback where the curve of the blade adds considerably to the downward force of a cutting action.

The tachi is a sword which is generally larger than a katana, and is worn suspended with the cutting edge down. This was the standard form of carrying the sword for centuries, and would eventually be displaced by the katana style where the blade was worn thrust through the belt, edge up. The tachi was worn slung across the left hip. The signature on the tang

(nakago) of the blade was inscribed in such a way that it would always be on the outside of the sword when worn. This characteristic is important in recognising the development, function and different styles of wearing swords from this time onwards.

When worn with full armour, the tachi would be accompanied by a shorter blade in the form known as koshigatana ("waist sword"); a type of short sword with no hand-guard (tsuba) and where the hilt and scabbard meet to form the style of mounting called an aikuchi ("meeting mouth"). Daggers (tantō), were also carried for close combat fighting as well as carried generally for personal protection.

The Mongol invasions of Japan

in the 13th century spurred further evolution of the Japanese sword. Often forced to abandon traditional mounted archery for hand-to-hand combat, many samurai found that their swords were too delicate and prone to damage when used against the thick leather armor of the invaders. In response, Japanese swordsmiths started to adopt thinner and simpler temper lines. Certain Japanese swordsmiths of this period began to make blades with thicker backs and bigger points as a response to the Mongol threat.

By the 15th century, the Sengoku Jidai

civil war erupted, and the vast need for swords together with the ferocity of the fighting caused the highly artistic techniques of the Kamakura period

(known as the "Golden Age of Swordmaking") to be abandoned in favor of more utilitarian and disposable weapons. The export of nihontō reached its height during the Muromachi period

when at least 200,000 nihontō were shipped to Ming Dynasty

China in official trade in an attempt to soak up the production of Japanese weapons and make it harder for pirates in the area to arm.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, samurai who increasingly found a need for a sword for use in closer quarters along with increasing use of foot-soldiers armed with spears led to the creation of the uchigatana

, in both one-handed and two-handed forms. As the Sengoku civil wars progressed, the uchigatana evolved into the modern katana

, and replaced the tachi as the primary weapon of the samurai, especially when not wearing armor. Many longer tachi were shortened in the 15th-17th centuries to meet the demand for katana.

The craft decayed as time progressed and firearm

s were introduced as a decisive force on the battlefield. At the end of the Muromachi period

, the Tokugawa shoguns issued regulations controlling who could own and carry swords, and effectively standardized the description of a nihontō.

Under the isolationist

Tokugawa shogunate

, swordmaking and the use of firearms declined. The master swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide (c.1750–1825) published opinions that the arts and techniques of the shintō swords were inferior to the kotō blades, and that research should be made by all swordsmiths to rediscover the lost techniques. Masahide traveled the land teaching what he knew to all who would listen, and swordsmiths rallied to his cause and ushered in a second renaissance in Japanese sword smithing . With the discarding of the shintō style, and the re-introduction of old and rediscovered techniques, swords made in the kotō style between 1761 and 1876 are , "new revival swords" or literally "new-new swords." These are considered superior to most shintō, but inferior to true kotō.

The arrival of Matthew Perry

in 1853 and the subsequent Convention of Kanagawa

forcibly reintroduced Japan to the outside world; the rapid modernization

of the Meiji Restoration

soon followed. The Haitorei edict

in 1876 all but banned carrying swords and guns on streets. Overnight, the market for swords died, many swordsmiths were left without a trade to pursue, and valuable skills were lost. The nihontō remained in use in some occupations such as the police force. At the same time, kendo

was incorporated into police training so that police officers would have at least the training necessary to properly use one.

In time, it was rediscovered that soldiers needed to be armed with swords, and over the decades at the beginning of the 20th century swordsmiths again found work. These swords, derisively called guntō, were often oil-tempered, or simply stamped out of steel and given a serial number rather than a chiseled signature. The mass-produced ones often look like Western cavalry sabers rather than nihontō, with blades slightly shorter than blades of the shintō and shinshintō periods.

Military swords hand made in the traditional way are often termed as gendaitō. The craft of making swords was kept alive through the efforts of a few individuals, notably Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一, 1836–1918) and Gassan Sadakatsu (月山貞勝, 1869–1943), who were employed as Imperial artisans. These smiths produced fine works that stand with the best of the older blades for the Emperor and other high ranking officials. The students of Sadakatsu went on to be designated Intangible Cultural Assets, "Living National Treasures," as they embodied knowledge that was considered to be fundamentally important to the Japanese identity. In 1934 the Japanese government issued a military specification for the shin guntō

(new army sword), the first version of which was the Type 94 Katana, and many machine- and hand-crafted swords used in World War II conformed to this and later shin guntō specifications.

all armed forces in occupied Japan

were disbanded and production of nihontō with edges was banned except under police or government permit. The ban was overturned through a personal appeal by Dr. Junji Honma. During a meeting with General Douglas MacArthur, Dr. Honma produced blades from the various periods of Japanese history and MacArthur was able to identify very quickly what blades held artistic merit and which could be considered purely weapons. As a result of this meeting, the ban was amended so that guntō weapons would be destroyed while swords of artistic merit could be owned and preserved. Even so, many nihontō were sold to American soldiers at a bargain price; in 1958 there were more Japanese swords in America than in Japan. The vast majority of these one million or more swords were guntō, but there were still a sizable number of older swords.

After the Edo period, swordsmiths turned increasingly to the production of civilian goods. The Occupation and its regulations almost put an end to the production of nihonto. A few smiths continued their trade, and Dr. Honma went on to be a founder of the , who made it their mission to preserve the old techniques and blades. Thanks to the efforts of other like-minded individuals, the nihontō did not disappear, many swordsmiths continued the work begun by Masahide, and the old swordmaking techniques were rediscovered.

Modern nihonto manufactured according to traditional methods are usually known as , meaning "newly made swords". Alternatively, they can be termed when they are designed for combat as opposed to iaitō

training swords.

Due to their popularity in modern media, display-only "nihontō" have become widespread in the sword marketplace. Ranging from small letter opener

s to scale replica "wallhangers", these items are commonly made from stainless steel

(which makes them either brittle or poor at holding an edge) and have either a blunt or very crude edge. There are accounts of good quality stainless steel nihontō, however, these are rare at best. Some replica nihontō have been used in modern-day armed robberies, which became the reason for a possible ban on sale, import and hire of samurai swords in the UK. As a part of marketing, modern a-historic blade styles and material properties are often stated as traditional and genuine, promulgating disinformation.

In Japan, genuine edged hand-made Japanese swords, whether antique or modern, are classified as art objects (and not weapons) and must have accompanying certification in order to be legally owned.

It should be noted that some companies and independent smiths outside of Japan produce katana as well, with varying levels of quality.

. Wakizashi were not simply scaled-down nihontō; they were often forged in hira-zukuri or other such forms which were very rare on nihontō.

The daishō was not always forged together. If a samurai

was able to afford a daishō, it was often composed of whichever two swords could be conveniently acquired, sometimes by different smiths and in different styles. Even when a daishō contained a pair of blades by the same smith, they were not always forged as a pair or mounted as one. Daishō made as a pair, mounted as a pair, and owned/worn as a pair, are therefore uncommon and considered highly valuable, especially if they still retain their original mountings (as opposed to later mountings, even if the later mounts are made as a pair).

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took weeks or even months and was considered a sacred art. As with many complex endeavors, rather than a single craftsman, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher (called a togi) as well as the various artisans that made the koshirae (the various fittings used to decorate the finished blade and saya (sheath) including the tsuka (hilt), fuchi (collar), kashira (pommel), and tsuba (hand guard)). It is said that the sharpening and polishing process takes just as long as the forging of the blade itself.

The legitimate Japanese sword is made from Japanese steel "Tamahagane". The most common lamination method the Japanese sword blade is formed from is a combination of two different steel

The legitimate Japanese sword is made from Japanese steel "Tamahagane". The most common lamination method the Japanese sword blade is formed from is a combination of two different steel

s: a harder outer jacket of steel wrapped around a softer inner core of steel. This creates a blade which has a unique hard, highly razor sharp cutting edge with the ability to absorb shocks in a way which reduces the possibility of the blade breaking or bending when used in combat. The hadagane, for the outer skin of the blade, is produced by heating a block of high quality raw steel, which is then hammered out into a bar, and the flexible back portion. This is then cooled and broken up into smaller blocks which are checked for further impurities and then reassembled and reforged. During this process the billet of steel is heated and hammered, split and folded back upon itself many times and re-welded to create a complex structure of many thousands of layers. Each different steel is folded differently to provide the necessary strength and flexibility to the different steels. The precise way in which the steel is folded, hammered and re-welded determines the distinctive grain pattern of the blade, the jihada, (also called jigane when referring to the actual surface of the steel blade) a feature which is indicative of the period, place of manufacture and actual maker of the blade. The practice of folding also ensures a somewhat more homogeneous product, with the carbon in the steel being evenly distributed and the steel having no voids that could lead to fractures and failure of the blade in combat.

The shingane (for the inner core of the blade) is of a relatively softer steel with a lower carbon content than the hadagane. For this, the block is again hammered, folded and welded in a similar fashion to the hadagane, but with fewer folds. At this point, the hadagane block is once again heated, hammered out and folded into a ‘U’ shape, into which the shingane is inserted to a point just short of the tip. The new composite steel billet is then heated and hammered out ensuring that no air or dirt is trapped between the two layers of steel. The bar increases in length during this process until it approximates the final size and shape of the finished sword blade. A triangular section is cut off from the tip of the bar and shaped to create what will be the kissaki. At this point in the process, the blank for the blade is of rectangular section. This rough shape is referred to as a sunobe.

The sunobe is again heated, section by section and hammered to create a shape which has many of the recognisable characteristics of the finished blade. These are a thick back (mune), a thinner edge (ha), a curved tip (kissaki), notches on the edge (hamachi) and back (munemachi) which separate the blade from the tang (nakago). Details such as the ridge line (shinogi) another distinctive characteristic of the Japanese sword, are added at this stage of the process. The smith’s skill at this point comes in to play as the hammering process causes the blade to naturally curve in an erratic way, the thicker back tending to curve towards the thinner edge, and he must skillfully control the shape to give it the required upward curvature. The sunobe is finished by a process of filing and scraping which leaves all the physical characteristics and shapes of the blade recognisable. The surface of the blade is left in a relatively rough state, ready for the hardening processes. The sunobe is then covered all over with a clay mixture which is applied more thickly along the back and sides of the blade than along the edge. The blade is left to dry while the smith prepares the forge for the final heat treatment of the blade, the yaki-ire, the hardening of the cutting edge.

This process takes place in a darkened smithy, traditionally at night, in order that the smith can judge by eye the colour and therefore the temperature of the sword as it is repeatedly passed through the glowing charcoal. When the time is deemed right (traditionally the blade should be the colour of the moon in February and August which are the two months that appear most commonly on dated inscriptions on the nakago of the Japanese sword), the blade is plunged edge down and point forward into a tank of water. The precise time taken to heat the sword, the temperature of the blade and of the water into which it is plunged are all individual to each smith and they have generally been closely guarded secrets. Legend tells of a particular smith who cut off his apprentice’s hand for testing the temperature of the water he used for the hardening process. In the different schools of swordmakers there are many subtle variations in the materials used in the various processes and techniques outlined above, specifically in the form of clay applied to the blade prior to the yaki-ire, but all follow the same general procedures.

The application of the clay in different thicknesses to the blade allows the steel to cool more quickly along the thinner coated edge when plunged into the tank of water and thereby develop into the harder form of steel called martensite

, which can be ground to razor-like sharpness. The thickly coated back cools more slowly retaining the pearlite

steel characteristics of relative softness and flexibility. The precise way in which the clay is applied, and partially scraped off at the edge, is a determining factor in the formation of the shape and features of the crystalline structure known as the hamon

. This distinctive tempering line found near the edge of the Japanese blade is one of the main characteristics to be assessed when examining a blade.

The martensitic steel which forms from the edge of the blade to the hamon is in effect the transition line between these two different forms of steel, and is where most of the shapes, colours and beauty in the steel of the Japanese sword are to be found. The variations in the form and structure of the hamon are all indicative of the period, smith, school or place of manufacture of the sword. As well as the aesthetic qualities of the hamon, there are, perhaps not unsurprisingly, real practical functions. The hardened edge is where most of any potential damage to the blade will occur in battle. This hardened edge is capable of being reground and sharpened many times, although the process will alter the shape of the blade. Altering the shape will allow more resistance when fighting in hand to hand combat.

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool, and the mud is scraped off, the blade may have designs or grooves (hi or bo-hi) cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the nakago or the hilt-section of the blade, where they will be covered by the tsuka later. The nakago is never supposed to be cleaned: doing this can reduce the value of the sword by half or more. The purpose is to show how well the blade steel ages.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: dedications written in kanji as well as engravings called horimono depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings. Some are more practical. The presence of a groove (the most basic type is called a hi) reduces the weight of the sword yet keeps its structural integrity and strength.

Testing of swords, called tameshigiri

, was practiced on a variety of materials (often the bodies of executed criminals) to test the sword's sharpness and practice cutting technique.

Kenjutsu

is the Japanese martial art of using the nihontō in combat. The nihontō was primarily a cutting weapon, or more specifically, a slicing one. However, the nihontō's moderate curve allows for effective thrusting as well. The hilt of the nihontō was held with two hands, though a fair amount of one-handed techniques exist. The placement of the right hand was dictated by both the length of the tsuka and the length of the wielder's arm. Two other martial arts were developed specifically for training to draw the sword and attack in one motion. They are battōjutsu

and iaijutsu

, which are superficially similar, but do generally differ in training theory and methods.

For cutting, there was a specific technique called "ten-uchi." Ten-uchi refers to an organized motion made by arms and wrist, during a descending strike. As the sword is swung downwards, the elbow joint drastically extends at the last instant, popping the sword into place. This motion causes the swordsman's grip to twist slightly and if done correctly, is said to feel like wringing a towel (Thomas Hooper-sensei reference). This motion itself caused the nihontō's blade to impact its target with sharp force, and is used to break initial resistance. From there, fluidly continuing along the motion wrought by ten-uchi, the arms would follow through with the stroke, dragging the sword through its target. Because the nihontō slices rather than chops, it is this "dragging" which allows it to do maximum damage, and is thus incorporated into the cutting technique. At full speed, the swing will appear to be full stroke, the nihontō passing through the targeted object. The segments of the swing are hardly visible, if at all. Assuming that the target is, for example, a human torso, ten-uchi will break the initial resistance supplied by shoulder muscles and the clavicle. The follow through would continue the slicing motion, through whatever else it would encounter, until the blade inherently exited the body, due to a combination of the motion and its curved shape.

Nearly all styles of kenjutsu share the same five basic guard postures. They are as follows; chūdan-no-kamae (middle posture), jōdan-no-kamae (high posture), gedan-no-kamae (low posture), hassō-no-kamae

(eight-sided posture), and waki-gamae (side posture).

The nihontō's razor-edge was so hard that upon hitting an equally hard or harder object, such as another sword's edge, chipping became a definite risk. As such, blocking an oncoming blow blade-to-blade was generally avoided. In fact, evasive body maneuvers were preferred over blade contact by most, but, if such was not possible, the flat or the back of the blade was used for defense in many styles, rather than the precious edge. A popular method for defeating descending slashes was to simply beat the sword aside. In some instances, an "umbrella block", positioning the blade overhead, diagonally (point towards the ground, pommel towards the sky), would create an effective shield against a descending strike. If the angle of the block was drastic enough, the curve of the nihontō's spine would cause the attacker's blade to slide along its counter and off to the side.

The nihontō would be carried in a saya (sheath) and tucked into the samurai's belt. Originally, they would carry the sword with the blade turned down. This was a more comfortable way for the armored samurai to carry his very long sword. The bulk of the samurai armor made it difficult to draw the sword from any other place on his body. When unarmored, samurai would carry their sword with the blade facing up. This made it possible to draw the sword and strike in one quick motion. In order to draw the sword, the samurai would turn the saya (sheath) downward ninety degrees and pull it out of his obi (sash) just a bit with his left hand, then gripping the tsuka (hilt) with his right hand he would slide it out while sliding the saya (sheath) back to its original position.

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.

Description

In modern times the most commonly known type of Japanese sword is the Shinogi-Zukuri katanaKatana

A Japanese sword, or , is one of the traditional bladed weapons of Japan. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.-Description:...

, which is a single-edged and usually curved long sword traditionally worn by samurai

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

from the 15th century onwards. Other types of Japanese swords include: tsurugi

Tsurugi

"Tsurugi" is a Japanese word used to refer to any type of broadsword, or those akin to the Chinese . The word is used in the West to refer to a specific type of Japanese straight, double-edged sword no longer in common use.-Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi:...

or ken, which is a double-edged sword; ōdachi

Odachi

An , was a type of long Japanese sword. The term nodachi, or "field sword", which refers to a different type of sword, is often mistakenly used in place of ōdachi. It is historically known as ōtachi....

, nodachi

Nodachi

A nodachi is a large two-handed Japanese sword. Some have suggested that the meaning of "nodachi" is roughly the same as ōdachi meaning "large/great sword". A confusion between the terms has nearly synonymized "nodachi" with the very large "ōdachi"...

, tachi

Tachi

The is one type of traditional Japanese sword worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan.-History and description:With a few exceptions katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other if signed, by the location of the signature on the tang...

, which are older styles of a very long single-edged sword; wakizashi

Wakizashi

The is one of the traditional Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

, a medium sized sword; and the tanto

Tanto

A is one of the traditional Japanese swords that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ornate...

which is an even smaller knife sized sword . Although they are pole-mounted weapons, the naginata

Naginata

The naginata is one of several varieties of traditionally made Japanese blades in the form of a pole weapon. Naginata were originally used by the samurai class in feudal Japan, and naginata were also used by ashigaru and sōhei .-Description:A naginata consists of a wooden shaft with a curved...

and yari

Yari

is the term for one of the traditionally made Japanese blades in the form of a spear, or more specifically, the straight-headed spear...

are considered part of the nihontō family due to the methods by which they are forged.

Japanese swords are still commonly seen today; antique and modernly-forged swords can easily be found and purchased. Modern, authentic nihontō are made by a few hundred swordsmiths. Many examples can be seen at an annual competition hosted by the All Japan Swordsmith Association, under the auspices of the Nihontō Bunka Shinkō Kyōkai (Society for the promotion of Japanese Sword Culture).

Etymology

The word katana was used in ancient Japan and is still used today, whereas the old usage of the word nihontō is found in the poem 日本刀歌, the Song of Nihontō, by the Song DynastySong Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a ruling dynasty in China between 960 and 1279; it succeeded the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, and was followed by the Yuan Dynasty. It was the first government in world history to issue banknotes or paper money, and the first Chinese government to establish a...

poet Ouyang Xiu

Ouyang Xiu

Ouyang Xiu was a Chinese statesman, historian, essayist and poet of the Song Dynasty. He is also known by his courtesy name of Yongshu, and was also self nicknamed The Old Drunkard 醉翁, or Householder of the One of Six 六一居士 in his old age...

. The word nihontō became more common in Japan in the late Tokugawa shogunate

Late Tokugawa shogunate

, literally "end of the curtain", are the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate came to an end. It is characterized by major events occurring between 1853 and 1867 during which Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as sakoku and transitioned from a feudal shogunate...

. Due to importation of Western swords, the word nihontō was adopted in order to distinguish it from the .

Blade

The shinogi can be placed near the back of the blade for a longer, sharper, more fragile tip or a more moderate shinogi near the center of the blade.

The sword also has an exact tip shape, which is considered an extremely important characteristic: the tip can be long (ōkissaki), medium (chūkissaki), short (kokissaki), or even hooked backwards (ikuri-ōkissaki). In addition, whether the front edge of the tip is more curved (fukura-tsuku) or (relatively) straight (fukura-kareru) is also important.

The kissaki (point) is not a "chisel-like" point, nor is the Western knife interpretation of a "tanto point" found on true Japanese swords; a straight, linearly-sloped point has the advantage of being easy to grind, but it bears only a superficial similarity to traditional Japanese kissaki. Kissaki have a curved profile, and smooth three-dimensional curvature across their surface towards the edge - though they are bounded by a straight line called the yokote and have crisp definition at all their edges.

Although it is not commonly known, the "chisel point" kissaki originated in Japan. Examples of such are shown in the book "The Japanese Sword" by Kanzan Sato. Because American bladesmiths use this design extensively it is a common misconception that the design originated in America.

A hole is punched through the tang nakago, called a mekugi-ana. It is used to anchor the blade using a mekugi, a small bamboo pin that is inserted into another cavity in the handle tsuka and through the mekugi-ana, thus restricting the blade from slipping out. To remove the tsuka one removes the mekugi. The swordsmith's signature mei is placed on the nakago.

Mountings

In Japanese, the scabbard for a nihontō is referred to as a saya, and the handguard piece, often intricately designed as an individual work of art — especially in later years of the Edo periodEdo period

The , or , is a division of Japanese history which was ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family, running from 1603 to 1868. The political entity of this period was the Tokugawa shogunate....

— was called the tsuba. Other aspects of the mountings (koshirae), such as the menuki (decorative grip swells), habaki (blade collar and scabbard wedge), fuchi and kashira (handle collar and cap), kozuka (small utility knife handle), kogai (decorative skewer-like implement), saya lacquer, and tsuka-ito (professional handle wrap, also named tsukamaki), received similar levels of artistry.

Length

However the historical shaku was slightly longer (13.96 inches or 35.45 cm). Thus, there may sometimes be confusion about the blade lengths, depending on which shaku value is being assumed when converting to metric or US measurements.

The three main divisions of Japanese blade length are:

- 1 shaku or less for tantōTantoA is one of the traditional Japanese swords that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ornate...

(knifeKnifeA knife is a cutting tool with an exposed cutting edge or blade, hand-held or otherwise, with or without a handle. Knives were used at least two-and-a-half million years ago, as evidenced by the Oldowan tools...

or daggerDaggerA dagger is a fighting knife with a sharp point designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon. The design dates to human prehistory, and daggers have been used throughout human experience to the modern day in close combat confrontations...

). - 1–2 shaku for (wakizashiWakizashiThe is one of the traditional Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

or kodachiKodachiA , literally translating into "small or short tachi ", is a Japanese sword that is too long to be considered a dagger but too short to be a long sword...

). - 2 shaku or more for (long sword, such as katanaKatanaA Japanese sword, or , is one of the traditional bladed weapons of Japan. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.-Description:...

or tachiTachiThe is one type of traditional Japanese sword worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan.-History and description:With a few exceptions katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other if signed, by the location of the signature on the tang...

).

A blade shorter than one shaku is considered a tantō (knife). A blade longer than one shaku but less than two is considered a shōtō (short sword). The wakizashi and kodachi

Kodachi

A , literally translating into "small or short tachi ", is a Japanese sword that is too long to be considered a dagger but too short to be a long sword...

are in this category. The length is measured in a straight line across the back of the blade from tip to munemachi (where blade meets tang

Tang (weaponry)

A tang or shank is the back portion of a tool where it extends into stock material or is connected to a handle as on a knife, sword, spear, arrowhead, chisel, screwdriver, etc...

). Most blades that fall into the "shōtō" size range are wakizashi

Wakizashi

The is one of the traditional Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

. However, some daitō were designed with blades slightly shorter than 2 shaku. These were called kodachi

Kodachi

A , literally translating into "small or short tachi ", is a Japanese sword that is too long to be considered a dagger but too short to be a long sword...

and are somewhere in between a true daitō and a wakizashi. A shōtō and a daitō together are called a daishō

Daisho

The is a Japanese term for a matched pair of traditionally made Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

(literally, "big and small"). The daishō was the symbolic armament of the Edo period

Edo period

The , or , is a division of Japanese history which was ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family, running from 1603 to 1868. The political entity of this period was the Tokugawa shogunate....

samurai

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

.

A blade longer than two shaku is considered a daitō, or long sword. To qualify as a daitō the sword must have a blade longer than 2 shaku (approximately 24 inches or 60 centimeters) in a straight line. While there is a well defined lower-limit to the length of a daitō, the upper limit is not well enforced; a number of modern historians, swordsmiths, etc. say that swords that are over 3 shaku in blade length are "longer than normal daitō" and are usually referred to or called ōdachi

Odachi

An , was a type of long Japanese sword. The term nodachi, or "field sword", which refers to a different type of sword, is often mistakenly used in place of ōdachi. It is historically known as ōtachi....

. The word "daitō" is often used when explaining the related terms shōtō (short sword) and daishō

Daisho

The is a Japanese term for a matched pair of traditionally made Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

(the set of both large and small sword). Miyamoto Musashi

Miyamoto Musashi

, also known as Shinmen Takezō, Miyamoto Bennosuke or, by his Buddhist name, Niten Dōraku, was a Japanese swordsman and rōnin. Musashi, as he was often simply known, became renowned through stories of his excellent swordsmanship in numerous duels, even from a very young age...

refers to the long sword in The Book of Five Rings. He is referring to the katana in this, and refers to the nodachi and the odachi as "extra-long swords".

Before 1500 most swords were usually worn suspended from cords on a belt, edge-down. This style is called jindachi-zukuri, and daitō worn in this fashion are called tachi (average blade length of 75–80 cm). From 1600 to 1867, more swords were worn through an obi

Obi (sash)

is a sash for traditional Japanese dress, keikogi worn for Japanese martial arts, and a part of kimono outfits.The obi for men's kimono is rather narrow, wide at most, but a woman's formal obi can be wide and more than long. Nowadays, a woman's wide and decorative obi does not keep the kimono...

(sash), paired with a smaller blade; both worn edge-up. This style is called buke-zukuri, and all daitō worn in this fashion are katana, averaging 70–74 cm (2 shaku 3 sun to 2 shaku 4 sun 5 bu) in blade length. However, nihontō of longer lengths also existed, including lengths up to 78 cm (2 shaku 5 sun 5 bu).

The weight of a nihontō rarely exceeded 1 kg without the saya.

It was not simply that the swords were worn by cords on a belt, as a 'style' of sorts. Such a statement trivializes an important function of such a manner of bearing the sword. It was a very direct example of 'form following function.' At this point in Japanese history, much of the warfare was fought on horseback. Being so, if the sword/blade were in a more vertical position, it would be cumbersome, and awkward to draw. Suspending the sword by 'cords,' allowed the sheath to be more horizontal, and far less likely to bind while drawing it in that position.

A is simply a shorter nihontō. It is longer than the wakizashi, usually about 18 inches in length. The most common reference to a chisa katana is a shorter nihontō that does not have a companion blade. They were most commonly made in the buke-zukuri mounting.

Abnormally long blades (longer than 3 shaku), usually carried across the back, are called ōdachi

Odachi

An , was a type of long Japanese sword. The term nodachi, or "field sword", which refers to a different type of sword, is often mistakenly used in place of ōdachi. It is historically known as ōtachi....

or nodachi

Nodachi

A nodachi is a large two-handed Japanese sword. Some have suggested that the meaning of "nodachi" is roughly the same as ōdachi meaning "large/great sword". A confusion between the terms has nearly synonymized "nodachi" with the very large "ōdachi"...

. The word ōdachi is also sometimes used as a synonym for nihontō. Odachi means "Great Sword", and Nodachi translates to "Field sword". Nodachi were used during war as the longer sword gave a foot soldier a reach advantage, but now nodachi are illegal because of their effectiveness as a killing weapon. Citizens are not allowed to possess an odachi unless it is for ceremonial purposes.

Here is a list of lengths for different types of swords:

- NodachiNodachiA nodachi is a large two-handed Japanese sword. Some have suggested that the meaning of "nodachi" is roughly the same as ōdachi meaning "large/great sword". A confusion between the terms has nearly synonymized "nodachi" with the very large "ōdachi"...

, ŌdachiOdachiAn , was a type of long Japanese sword. The term nodachi, or "field sword", which refers to a different type of sword, is often mistakenly used in place of ōdachi. It is historically known as ōtachi....

, Jin tachi: 90 cm and over (more than three shaku) - TachiTachiThe is one type of traditional Japanese sword worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan.-History and description:With a few exceptions katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other if signed, by the location of the signature on the tang...

, KatanaKatanaA Japanese sword, or , is one of the traditional bladed weapons of Japan. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.-Description:...

: over 60.6 cm (more than two shaku) - WakizashiWakizashiThe is one of the traditional Japanese swords worn by the samurai class in feudal Japan.-Description:...

: between 30.3–60.6 cm (between one and two shaku) - TantōTantoA is one of the traditional Japanese swords that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ornate...

, Aikuchi: under 30.3 cm (under one shaku)

Swords whose length is next to a different classification type are described with a prefix 'O-' (for great) or 'Ko-' (for small), e.g. a Wakizashi with a length of 59 cm is called a O-wakizashi (almost a Katana) whereas a Katana with 61 cm is called a Ko-Katana (for small Katana) .

Since 1867, restrictions and/or the deconstruction of the samurai class meant that most blades have been worn jindachi-zukuri style, like Western navy officers. Since 1953, there has been a resurgence in the buke-zukuri style, permitted only for demonstration purposes. Swords designed specifically to be tachi are generally kotō rather than shintō, so they are generally better manufactured and more elaborately decorated, however, these are still katana if worn in modern buke-zukuri style.

School

Most old Japanese swords can be traced back to one of five provinces, each of which had its own school, traditions and "trademarks" (e.g., the swords from Mino province were "from the start famous for their sharpness"). These schools are known as Gokaden (The Five Traditions). These traditions and provinces are as follows:- SōshūSagami Provincewas an old province in the area that is today the central and western Kanagawa prefecture. It was sometimes called . Sagami bordered on Izu, Musashi, Suruga provinces; and had access to the Pacific Ocean through Sagami Bay...

School, known for itame hada and midareba hamon in nie deki. - YamatoYamato Provincewas a province of Japan, located in Kinai, corresponding to present-day Nara Prefecture in Honshū. It was also called . At first, the name was written with one different character , and for about ten years after 737, this was revised to use more desirable characters . The final revision was made in...

School, known for masame hada and suguha hamon in nie deki. - BizenBizen Provincewas a province of Japan on the Inland Sea side of Honshū, in what is today the southeastern part of Okayama Prefecture. It was sometimes called , with Bitchu and Bingo Provinces. Bizen borders Mimasaka, Harima, and Bitchū Provinces....

School, known for mokume hada and midareba hamon in nioi deki. - YamashiroYamashiro Provincewas a province of Japan, located in Kinai. It overlaps the southern part of modern Kyoto Prefecture on Honshū. Aliases include , the rare , and . It is classified as an upper province in the Engishiki....

School, known for mokume hada and suguha hamon in nei deki. - MinoMino Province, one of the old provinces of Japan, encompassed part of modern-day Gifu Prefecture. It was sometimes called . Mino Province bordered Echizen, Hida, Ise, Mikawa, Ōmi, Owari, and Shinano Provinces....

School, known for hard mokume hada and midareba mixed with togari-ba.

In the Kotō era there were several other schools that did not fit within the Gokaden or were known to mix elements of each Gokaden, and they were called wakimono (small school). There were 19 commonly referenced wakimono.

Early history

Chokuto

The is a type of Japanese sword that dates back to pre-Heian times. Chokutō were made in later periods, but usually as temple offering swords. Chokutō were straight and single-edged hacking swords. That chokutō's design was originally imported to Japan from China, though seemingly most often...

or jōkotō and others with unusual shapes. In the Heian period

Heian period

The is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. The period is named after the capital city of Heian-kyō, or modern Kyōto. It is the period in Japanese history when Buddhism, Taoism and other Chinese influences were at their height...

(8th to 11th centuries) sword-making developed through techniques brought over from China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

through trade in the early 10th century during the Tang Dynasty

Tang Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty was an imperial dynasty of China preceded by the Sui Dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period. It was founded by the Li family, who seized power during the decline and collapse of the Sui Empire...

and through Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

and Hokkaidō

Hokkaido

, formerly known as Ezo, Yezo, Yeso, or Yesso, is Japan's second largest island; it is also the largest and northernmost of Japan's 47 prefectural-level subdivisions. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaido from Honshu, although the two islands are connected by the underwater railway Seikan Tunnel...

, territory of the Ainu people

Ainu people

The , also called Aynu, Aino , and in historical texts Ezo , are indigenous people or groups in Japan and Russia. Historically they spoke the Ainu language and related varieties and lived in Hokkaidō, the Kuril Islands, and much of Sakhalin...

. The Ainu used and these influenced the nihontō, which was held with two hands and designed for cutting, rather than stabbing. According to legend, the Japanese sword was invented by a smith named Amakuni

Amakuni

is the legendary swordsmith who created the first single-edged longsword with curvature along the edge in the Yamato Province around 700 AD. He was the head of a group of swordsmiths employed by the Emperor of Japan to make weapons for his warriors. His son, Amakura, was the successor to his work...

(ca.700 AD), along with the folded steel process. The folded steel process and single edge swords had been invented in the early 10th century Japan. Swords forged between 987 and 1597 are called (lit., "old swords"); these are considered the pinnacle of Japanese swordcraft. Early models had uneven curves with the deepest part of the curve at the hilt

Hilt

The hilt of a sword is its handle, consisting of a guard,grip and pommel. The guard may contain a crossguard or quillons. A ricasso may also be present, but this is rarely the case...

. As eras changed the center of the curve tended to move up the blade.

The nihonto as we know it today with its deep, graceful curve has its origin in shinogi-zukuri (single-edged blade with ridgeline) tachi

Tachi

The is one type of traditional Japanese sword worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan.-History and description:With a few exceptions katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other if signed, by the location of the signature on the tang...

which were developed sometime around the middle of the Heian period to service the need of the growing military class. Its shape reflects the changing form of warfare in Japan. Cavalry were now the predominant fighting unit and the older straight chokutō were particularly unsuitable for fighting from horseback. The curved sword is a far more efficient weapon when wielded by a warrior on horseback where the curve of the blade adds considerably to the downward force of a cutting action.

The tachi is a sword which is generally larger than a katana, and is worn suspended with the cutting edge down. This was the standard form of carrying the sword for centuries, and would eventually be displaced by the katana style where the blade was worn thrust through the belt, edge up. The tachi was worn slung across the left hip. The signature on the tang

Tang (weaponry)

A tang or shank is the back portion of a tool where it extends into stock material or is connected to a handle as on a knife, sword, spear, arrowhead, chisel, screwdriver, etc...

(nakago) of the blade was inscribed in such a way that it would always be on the outside of the sword when worn. This characteristic is important in recognising the development, function and different styles of wearing swords from this time onwards.

When worn with full armour, the tachi would be accompanied by a shorter blade in the form known as koshigatana ("waist sword"); a type of short sword with no hand-guard (tsuba) and where the hilt and scabbard meet to form the style of mounting called an aikuchi ("meeting mouth"). Daggers (tantō), were also carried for close combat fighting as well as carried generally for personal protection.

The Mongol invasions of Japan

Mongol invasions of Japan

The ' of 1274 and 1281 were major military efforts undertaken by Kublai Khan to conquer the Japanese islands after the submission of Goryeo to vassaldom. Despite their ultimate failure, the invasion attempts are of macrohistorical importance, because they set a limit on Mongol expansion, and rank...

in the 13th century spurred further evolution of the Japanese sword. Often forced to abandon traditional mounted archery for hand-to-hand combat, many samurai found that their swords were too delicate and prone to damage when used against the thick leather armor of the invaders. In response, Japanese swordsmiths started to adopt thinner and simpler temper lines. Certain Japanese swordsmiths of this period began to make blades with thicker backs and bigger points as a response to the Mongol threat.

By the 15th century, the Sengoku Jidai

Sengoku period

The or Warring States period in Japanese history was a time of social upheaval, political intrigue, and nearly constant military conflict that lasted roughly from the middle of the 15th century to the beginning of the 17th century. The name "Sengoku" was adopted by Japanese historians in reference...

civil war erupted, and the vast need for swords together with the ferocity of the fighting caused the highly artistic techniques of the Kamakura period

Kamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura Shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo....

(known as the "Golden Age of Swordmaking") to be abandoned in favor of more utilitarian and disposable weapons. The export of nihontō reached its height during the Muromachi period

Muromachi period

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate, which was officially established in 1338 by the first Muromachi shogun, Ashikaga Takauji, two years after the brief Kemmu restoration of imperial...

when at least 200,000 nihontō were shipped to Ming Dynasty

Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty, also Empire of the Great Ming, was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty. The Ming, "one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history", was the last dynasty in China ruled by ethnic...

China in official trade in an attempt to soak up the production of Japanese weapons and make it harder for pirates in the area to arm.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, samurai who increasingly found a need for a sword for use in closer quarters along with increasing use of foot-soldiers armed with spears led to the creation of the uchigatana

Uchigatana

The is one type type of traditional Japanese sword worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The uchigatana was the descendant of the tachi.-History:...

, in both one-handed and two-handed forms. As the Sengoku civil wars progressed, the uchigatana evolved into the modern katana

Katana

A Japanese sword, or , is one of the traditional bladed weapons of Japan. There are several types of Japanese swords, according to size, field of application and method of manufacture.-Description:...

, and replaced the tachi as the primary weapon of the samurai, especially when not wearing armor. Many longer tachi were shortened in the 15th-17th centuries to meet the demand for katana.

The craft decayed as time progressed and firearm

Firearm

A firearm is a weapon that launches one, or many, projectile at high velocity through confined burning of a propellant. This subsonic burning process is technically known as deflagration, as opposed to supersonic combustion known as a detonation. In older firearms, the propellant was typically...

s were introduced as a decisive force on the battlefield. At the end of the Muromachi period

Muromachi period

The is a division of Japanese history running from approximately 1336 to 1573. The period marks the governance of the Muromachi or Ashikaga shogunate, which was officially established in 1338 by the first Muromachi shogun, Ashikaga Takauji, two years after the brief Kemmu restoration of imperial...

, the Tokugawa shoguns issued regulations controlling who could own and carry swords, and effectively standardized the description of a nihontō.

New swords

In times of peace, swordsmiths returned to the making of refined and artistic blades, and the beginning of the Momoyama period saw the return of high quality creations. As the techniques of the ancient smiths had been lost during the previous period of war, these swords were called , literally "new swords". Generally they are considered inferior to most kotō ("old swords"), and coincide with a decline in manufacturing skills. As the Edo period progressed, blade quality declined, though ornamentation was refined. Originally, simple and tasteful engravings known as horimono were added for religious reasons. Later, in the more complex work found on many shintō, form no longer strictly followed function.Under the isolationist

Isolationism

Isolationism is the policy or doctrine of isolating one's country from the affairs of other nations by declining to enter into alliances, foreign economic commitments, international agreements, etc., seeking to devote the entire efforts of one's country to its own advancement and remain at peace by...

Tokugawa shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

, swordmaking and the use of firearms declined. The master swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide (c.1750–1825) published opinions that the arts and techniques of the shintō swords were inferior to the kotō blades, and that research should be made by all swordsmiths to rediscover the lost techniques. Masahide traveled the land teaching what he knew to all who would listen, and swordsmiths rallied to his cause and ushered in a second renaissance in Japanese sword smithing . With the discarding of the shintō style, and the re-introduction of old and rediscovered techniques, swords made in the kotō style between 1761 and 1876 are , "new revival swords" or literally "new-new swords." These are considered superior to most shintō, but inferior to true kotō.

The arrival of Matthew Perry

Matthew Perry (naval officer)

Matthew Calbraith Perry was the Commodore of the U.S. Navy and served commanding a number of US naval ships. He served several wars, most notably in the Mexican-American War and the War of 1812. He played a leading role in the opening of Japan to the West with the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854...

in 1853 and the subsequent Convention of Kanagawa

Convention of Kanagawa

On March 31, 1854, the or was concluded between Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy and the Tokugawa shogunate.-Treaty of Peace and Amity :...

forcibly reintroduced Japan to the outside world; the rapid modernization

Modernization

In the social sciences, modernization or modernisation refers to a model of an evolutionary transition from a 'pre-modern' or 'traditional' to a 'modern' society. The teleology of modernization is described in social evolutionism theories, existing as a template that has been generally followed by...

of the Meiji Restoration

Meiji Restoration

The , also known as the Meiji Ishin, Revolution, Reform or Renewal, was a chain of events that restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868...

soon followed. The Haitorei edict

Haitorei Edict

The was an edict issued by the Meiji government of Japan on March 28, 1876 which prohibited people, with the exception of the military and law enforcement officials, from carrying weapons in public. Violators would have their swords confiscated....

in 1876 all but banned carrying swords and guns on streets. Overnight, the market for swords died, many swordsmiths were left without a trade to pursue, and valuable skills were lost. The nihontō remained in use in some occupations such as the police force. At the same time, kendo

Kendo

, meaning "Way of The Sword", is a modern Japanese martial art of sword-fighting based on traditional Japanese swordsmanship, or kenjutsu.Kendo is a physically and mentally challenging activity that combines strong martial arts values with sport-like physical elements.-Practitioners:Practitioners...

was incorporated into police training so that police officers would have at least the training necessary to properly use one.

In time, it was rediscovered that soldiers needed to be armed with swords, and over the decades at the beginning of the 20th century swordsmiths again found work. These swords, derisively called guntō, were often oil-tempered, or simply stamped out of steel and given a serial number rather than a chiseled signature. The mass-produced ones often look like Western cavalry sabers rather than nihontō, with blades slightly shorter than blades of the shintō and shinshintō periods.

Military swords hand made in the traditional way are often termed as gendaitō. The craft of making swords was kept alive through the efforts of a few individuals, notably Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一, 1836–1918) and Gassan Sadakatsu (月山貞勝, 1869–1943), who were employed as Imperial artisans. These smiths produced fine works that stand with the best of the older blades for the Emperor and other high ranking officials. The students of Sadakatsu went on to be designated Intangible Cultural Assets, "Living National Treasures," as they embodied knowledge that was considered to be fundamentally important to the Japanese identity. In 1934 the Japanese government issued a military specification for the shin guntō

Shin gunto

The was a weapon and badge of rank used by the Imperial Japanese Army between the years of 1935 and 1945. During most of that period, the swords were manufactured at the Toyokawa Naval Arsenal.- Creation of a new army sword :...

(new army sword), the first version of which was the Type 94 Katana, and many machine- and hand-crafted swords used in World War II conformed to this and later shin guntō specifications.

Recent history and modern use

Under the United States occupation at the end of World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

all armed forces in occupied Japan

Occupied Japan

At the end of World War II, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States with contributions also from Australia, India, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. This foreign presence marked the first time in its history that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power...

were disbanded and production of nihontō with edges was banned except under police or government permit. The ban was overturned through a personal appeal by Dr. Junji Honma. During a meeting with General Douglas MacArthur, Dr. Honma produced blades from the various periods of Japanese history and MacArthur was able to identify very quickly what blades held artistic merit and which could be considered purely weapons. As a result of this meeting, the ban was amended so that guntō weapons would be destroyed while swords of artistic merit could be owned and preserved. Even so, many nihontō were sold to American soldiers at a bargain price; in 1958 there were more Japanese swords in America than in Japan. The vast majority of these one million or more swords were guntō, but there were still a sizable number of older swords.

After the Edo period, swordsmiths turned increasingly to the production of civilian goods. The Occupation and its regulations almost put an end to the production of nihonto. A few smiths continued their trade, and Dr. Honma went on to be a founder of the , who made it their mission to preserve the old techniques and blades. Thanks to the efforts of other like-minded individuals, the nihontō did not disappear, many swordsmiths continued the work begun by Masahide, and the old swordmaking techniques were rediscovered.

Modern nihonto manufactured according to traditional methods are usually known as , meaning "newly made swords". Alternatively, they can be termed when they are designed for combat as opposed to iaitō

Iaito

is the name given by practitioners of iaido to , literally meaning "mock" or "imitation sword", an imitation katana used for practicing some Japanese sword arts. A real or "live" Japanese sword is often called a shinken.-Materials and manufacture:...

training swords.

Due to their popularity in modern media, display-only "nihontō" have become widespread in the sword marketplace. Ranging from small letter opener

Letter opener

A paper knife or letter opener is a knife-like object used to open envelopes or to slit uncut pages of books. Electric versions are also available, which work by using motors to slide the envelopes across a blade...

s to scale replica "wallhangers", these items are commonly made from stainless steel

Stainless steel

In metallurgy, stainless steel, also known as inox steel or inox from French "inoxydable", is defined as a steel alloy with a minimum of 10.5 or 11% chromium content by mass....

(which makes them either brittle or poor at holding an edge) and have either a blunt or very crude edge. There are accounts of good quality stainless steel nihontō, however, these are rare at best. Some replica nihontō have been used in modern-day armed robberies, which became the reason for a possible ban on sale, import and hire of samurai swords in the UK. As a part of marketing, modern a-historic blade styles and material properties are often stated as traditional and genuine, promulgating disinformation.

In Japan, genuine edged hand-made Japanese swords, whether antique or modern, are classified as art objects (and not weapons) and must have accompanying certification in order to be legally owned.

It should be noted that some companies and independent smiths outside of Japan produce katana as well, with varying levels of quality.

Manufacturing

Nihontō and wakizashi were often forged with different profiles, different blade thicknesses, and varying amounts of grindGrind

The grind of a blade refers to the shape of the cross-section of the blade. It is distinct from the type of blade , though different tools and blades may have lent their name to a particular grind.Grinding involves removing significant portions of metal from the blade and is thus distinct from...

. Wakizashi were not simply scaled-down nihontō; they were often forged in hira-zukuri or other such forms which were very rare on nihontō.

The daishō was not always forged together. If a samurai

Samurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

was able to afford a daishō, it was often composed of whichever two swords could be conveniently acquired, sometimes by different smiths and in different styles. Even when a daishō contained a pair of blades by the same smith, they were not always forged as a pair or mounted as one. Daishō made as a pair, mounted as a pair, and owned/worn as a pair, are therefore uncommon and considered highly valuable, especially if they still retain their original mountings (as opposed to later mountings, even if the later mounts are made as a pair).

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took weeks or even months and was considered a sacred art. As with many complex endeavors, rather than a single craftsman, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher (called a togi) as well as the various artisans that made the koshirae (the various fittings used to decorate the finished blade and saya (sheath) including the tsuka (hilt), fuchi (collar), kashira (pommel), and tsuba (hand guard)). It is said that the sharpening and polishing process takes just as long as the forging of the blade itself.

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

s: a harder outer jacket of steel wrapped around a softer inner core of steel. This creates a blade which has a unique hard, highly razor sharp cutting edge with the ability to absorb shocks in a way which reduces the possibility of the blade breaking or bending when used in combat. The hadagane, for the outer skin of the blade, is produced by heating a block of high quality raw steel, which is then hammered out into a bar, and the flexible back portion. This is then cooled and broken up into smaller blocks which are checked for further impurities and then reassembled and reforged. During this process the billet of steel is heated and hammered, split and folded back upon itself many times and re-welded to create a complex structure of many thousands of layers. Each different steel is folded differently to provide the necessary strength and flexibility to the different steels. The precise way in which the steel is folded, hammered and re-welded determines the distinctive grain pattern of the blade, the jihada, (also called jigane when referring to the actual surface of the steel blade) a feature which is indicative of the period, place of manufacture and actual maker of the blade. The practice of folding also ensures a somewhat more homogeneous product, with the carbon in the steel being evenly distributed and the steel having no voids that could lead to fractures and failure of the blade in combat.

The shingane (for the inner core of the blade) is of a relatively softer steel with a lower carbon content than the hadagane. For this, the block is again hammered, folded and welded in a similar fashion to the hadagane, but with fewer folds. At this point, the hadagane block is once again heated, hammered out and folded into a ‘U’ shape, into which the shingane is inserted to a point just short of the tip. The new composite steel billet is then heated and hammered out ensuring that no air or dirt is trapped between the two layers of steel. The bar increases in length during this process until it approximates the final size and shape of the finished sword blade. A triangular section is cut off from the tip of the bar and shaped to create what will be the kissaki. At this point in the process, the blank for the blade is of rectangular section. This rough shape is referred to as a sunobe.